Designing for Social Justice: A Decolonial Exploration of How to Develop EdTech for Refugees

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions

- What can the lens of decoloniality add to the evidence of “what works” when using technology for refugee education?

- How can our current understanding of existing decolonial education frameworks, as well as lived experiences of refugees in Rwanda and Pakistan, help us move towards decolonising EdTech products, policies and interventions for refugees?

1.2. Dilemmas and Paradoxes

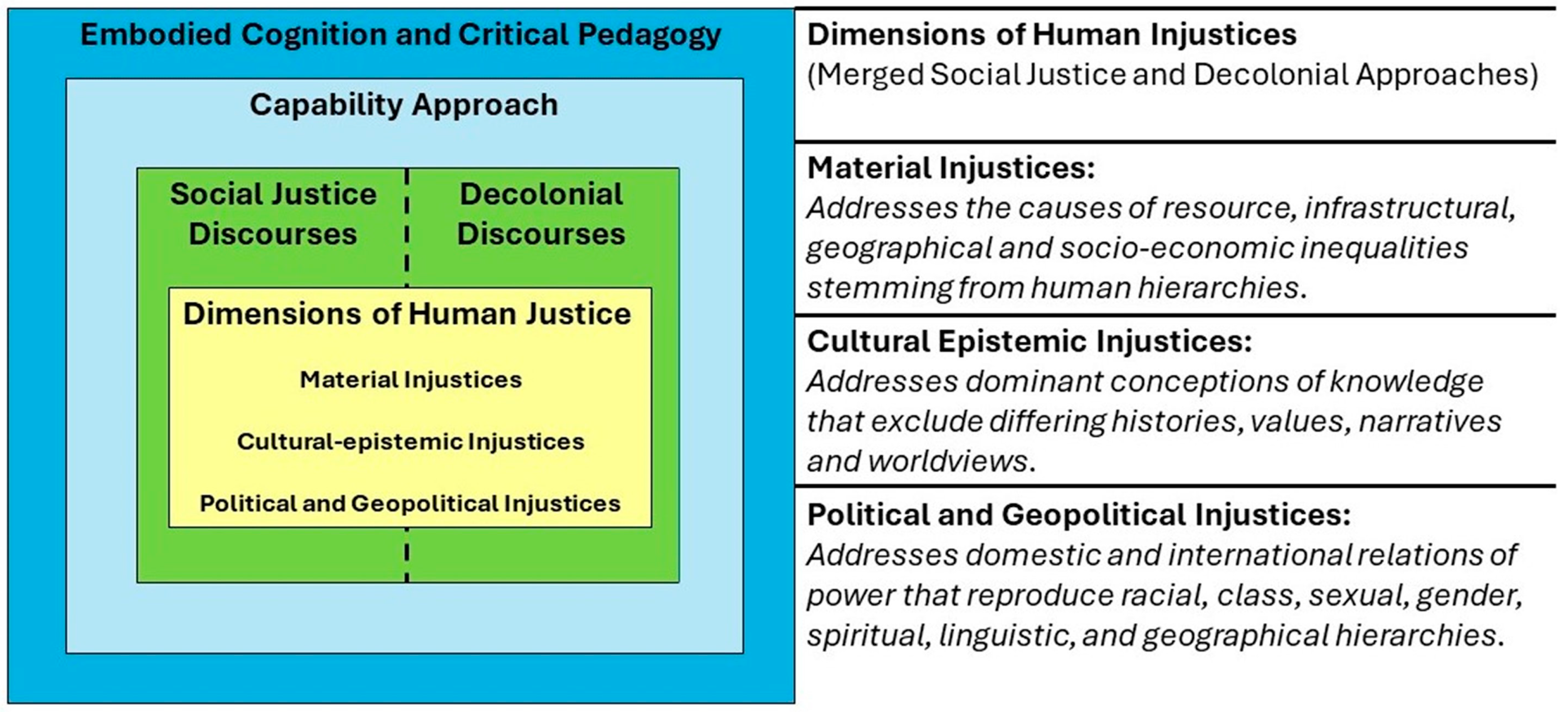

2. Analytical Framework

3. Literature Review

3.1. Historic Trends in Education for Refugees

3.2. Use of Education Technology in Emergency Responses

3.3. Designing EdTech for Refugees

3.4. Research Contexts

3.4.1. Pakistan

3.4.2. Rwanda

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling Approach

- Between 18 and 35 years old;

- Based in either Pakistan or Rwanda;

- Experience of using EdTech to access education post-displacement;

- Refugee status at the time of engaging in EdTech.

4.2. Data Collection Method

4.3. Analysis Approach

4.4. Ethical Considerations

4.5. Limitations

5. Results

5.1. Displacement Narratives

5.1.1. Pakistan (Females)

“I went to the hospital with a friend on my first day here. We spoke Farsi, and the guy noticed us not being Pakistani, so he charged us more… When you look for a house to rent initially, the owner doesn’t want to rent his house to refugees, and then he asks for double the price. We need support, but we get the opposite”.(PK1-H)

“Are we unlucky because we are born Afghan women, or is it the world ignoring us because we are Afghan? Nobody thinks about the benefits [our] education can provide to boost the economy. We hear empty words from organisations and activists, but don’t see action”.(PK1-G)

5.1.2. Pakistan (Males)

5.1.3. Rwanda

5.2. Refugee Participants’ Experiences of EdTech

5.2.1. Focus Products and Reasons for Engaging with Them

5.2.2. Positive Interactions with EdTech

“[E]verything was designed taking into account local accounting context. The examples given in the documents and videos were all Rwandese case studies, which allowed me to easily understand the content of the modules… it could allow me to integrate myself in the Rwandese accounting industry”.(RW-F)

“Ted Ed is in English, but it provides visuals which can make viewers understand a little, and seeing the captions and having the support of a family member and friend can help”.(PK1-F)

5.2.3. Barriers to EdTech Use

“I also had challenges at the beginning of my refugee life, because I had no laptop, and I had to use the phone to learn. My phone could not allow scripts, and I was hardly able to understand everything”.(RW-A)

“Refugees do not have access to paid websites… We are not provided with cards from the bank, and we cannot use e-services. We are provided with cheque books only, not even ATM [access] often. So we can’t use these learning resources even if we want to”.(PK1-A)

“[T]he courses were from American or British universities, and it was hard for me to feel comfortable with the programme in its essence due to my familiarity with Burundian education system mostly based on memorisation. I remember having failed in many quizzes at the beginning because I could not [understand] what I had watched in the videos… The context (examples given in the videos) was not familiar to me, and this was also a challenge”.(RW-C)

“Although the course was not tailored for refugees, we made sure to tailor ourselves and our capabilities to learn from it”.(PK2-E)

“I think I have to conform to the context… The other students may be familiar with the whole content, and to be able to get that degree, I have to make efforts and find ways of fitting into the context”.(RW-B)

“I am not very fond of tech, but now I am getting used to it because it is an essential part of learning today”.(PK1-D)

5.3. EdTech Product Design Ideas

5.3.1. What Should Be the Goal of Learning through EdTech?

“Refugee youth need to gain skills that can help them to be competitive in the job market. I think every EdTech product should take into account building theoretical content that is relevant to the current demands, and enabling refugee youth to know the realities of their host community; which can facilitate their full integration”.(RW-F)

5.3.2. What Format Should EdTech Products Take?

5.3.3. Who Should Design EdTech for Refugees?

“These people think they are experts and don’t value our voices and opinions, resulting in failed schemes. We need to play a role in decision-making processes because it will contribute to developing the refugee community”.(PK1-E)

5.3.4. What Content Should Be Covered?

“I think training programs to make them stand on their own feet instead of asking for support, especially for women: beautician courses and cooking courses, baking cakes, designing, these all are a great idea to help them [women] build their lives and contribute to the host community in general”.(PK1-D)

“Learning and understanding English will provide access to a wealth of content online, making it easier to learn and understand other subjects”.(PK2-C)

“Initially, we need to teach the refugee community about its value, teaching them to stand up for themselves and how to cope with discrimination and feeling of isolation. We need to target areas that will provide them with support for the trauma they have been through and the sense of isolation they experience. Inclusion can only begin by teaching refugees ways to include themselves”.(PK1-A)

“[T]he content of that EdTech product should be adapted to the local programmes, because it is obvious that Coursera does not include programmes from the many African universities. I am not even sure if the African universities have their programmes on Coursera”.(RW-A)

“I think it should not only focus on the local programme… We are now in a global education… We have foreign companies here which need people with global skills”.(RW-D)

5.3.5. How Should EdTech Learning Be Delivered?

“Our Afghan refugee community who have been here in Pakistan can provide great knowledge and skills to other refugees. They are talented and understand the refugee situation”.(PK1-E)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

- Prioritise designing diverse EdTech products for and with refugees. Refugees are not a homogenous group. Many refugees report that EdTech access is important for their educational success and future prosperity. However, there are very few EdTech offerings that design specifically with and for refugee communities. Rather than aiming for maximum reach and universality, funders and designers should consider focusing their efforts on designing for particular refugee groups, which will involve careful research within different refugee groups’ contexts, needs, and priorities. Additionally, in order to avoid disruption to learning progression, the sustainability of products should be considered from the outset.

- Actively seek refugee involvement and relational accountability in EdTech design. Although the vast majority of participants noted they would be eager to be involved, none report contribution to the design and/or development of EdTech products (though we acknowledge the small sample). They also report that their communities involve people with different professional skills and expertise (though the breadth of educational experiences and attainment among our participants, we argue, should not be discounted) who can be employed for both consultation on design and facilitation/presentation of the educational content. Doing so will ensure that products are not only contextually relevant, but genuinely empowering for the refugees that use them. It also acknowledges that design is a process of mutual accountability, learning and unlearning rather than a technical fix or end product [28]. The level of this involvement should also be decided by refugees themselves; some may wish to offer their perspectives only, while others may wish to assume a more decision-making role. Fair compensations should be offered for such consultations, commensurate with the time and effort spent.

- Design for maximum adaptability. Given the diverse needs and preferences of participating refugees, a sensible way forward for refugee EdTech design may be to focus efforts on designing products with high potential for adaptability. Rather than using such tools to distribute ‘universal’ content, models that provide a ‘shell’ within which content can be added and adapted by refugee actors for their own specific contexts may enable refugees to take greater ownership of, and a stronger decision-making role within, design processes for the EdTech products they use.

- Design for holistic interventions. As outlined, the refugee situation is complex, it has political, cultural–epistemic and material facets to it. A holistic intervention would first ensure that multiple stakeholders from across these multiple facets are part of the design process, i.e., that design is in conversation with policy and community. Second, holistic interventions would prioritise both survival skills, host-community integration, social and legal protection from exploitation as well as cultural affirmation and empowering refugees to build a communal narrative of being active agents, critically conscious of their realities and the forces producing it, rather than conforming subjects to the status quo.

- Raise awareness of power dynamics in parallel with design. Given the apparent lack of awareness of the sources of oppression that refugee participants experience, an important next step could be to increase efforts to engage with refugees about the reasons (and actors) behind their alienating experiences, in order to better equip them to identify and critically analyse the injustices they face [15] and reassert themselves within structures from which they continue to be excluded. How and by whom this is done should be the subject of further discussion.

- Educate designers into the historical context of refugees and the multiple dimensions of injustice. This starts by acknowledging epistemic limitations of designers and their experiences and the need to understand the complex political, historical, linguistic and psychological realities of the particular refugee group they are designing for. This would avoid reproducing systematic disempowerment. Scaife et al. [40] encourage “shaping the design at different points; for example, at the beginning to help problematize the domain, in the middle to test out and reflect on cognitive and design assumptions and biases, and at the end to evaluate prototypes in real-world contexts” (p. 350).

- Assess harm and accountability when it comes to data collection and ethics. Krishnan [55] developed a “Humanitarian Tech Ethics Assessment Considerations” framework (p. 8) to be applied in humanitarian settings to assess “plausible, possible and probable future harm”, taking into account decolonial principles. Such a framework can be a guide to designers, organisations and governments towards more transparency and accountability during data collection and usage in refugee education contexts. Indeed, the framework could be a helpful guide for the participating refugees themselves to understand possible risks and mitigations.

- Prioritise environmental sustainability when designing both hardware and software. Open systems that can be tinkered with and repaired have more scope to be used in the long-term. This is particularly important for refugees who may not have significant savings or disposable income to buy new technology, but they may well have the means to repair what they already have, and importantly will know how to use existing tools.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Timmis, S.; Muhuro, P. De-coding or de-colonising the technocratic university? Rural students’ digital transitions to South African higher education. Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D.; Jordan, K.; Wilson, S. Support provided for K-12 teachers teaching remotely with technology during emergencies: A systematic review. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2021, 54, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Habsi, S.; Rude, B. Refugee Education 4.0: The Potential and Pitfalls of EdTech for Refugee Education. CESifo Forum 2021, 22, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tauson, M.; Stannard, L. Edtech for Learning in Emergencies and Displaced Settings—A Rigorous Review and Narrative Synthesis; Save the Children: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/content/dam/global/reports/education-and-child-protection/edtech-learning.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Ashlee, A.; Clericetti, G.; Mitchell, J. Rapid Evidence Review: Refugee Education; EdTech Hub: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T. Addressing Injustices through MOOCs: A Study among Peri-Urban, Marginalised, South African Youth. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, J. #LTHEchat 220: Decolonising Learning Technology. Led by Professor John Traxler @johntraxler. #LTHEchat. Available online: https://lthechat.com/2021/11/28/lthechat-220-decolonising-learning-technology-led-by-professor-john-traxler-johntraxler/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Maldonado-Torres, N. Césaire’s Gift and the Decolonial Turn. In Critical Ethnic Studies; Elia, N., Hernández, D.M., Kim, J., Redmond, S.L., Rodríguez, D., See, S.E., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016; pp. 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice: Original Edition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World. New Left Rev. 2005, 36, 69–88. Available online: https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii36/articles/nancy-fraser-reframing-justice-in-a-globalizing-world (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Luckett, K.; Shay, S. Reframing the curriculum: A transformative approach. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2017, 61, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson-Williams, C.A.; Trotter, H. A social justice framework for understanding open educational resources and practices in the Global South. J. Learn. Dev. 2018, 5, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.R. Changing our (Dis)Course: A Distinctive Social Justice Aligned Definition of Open Education’. J. Learn. Dev. 2018, 5, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.M. Capabilities and Social Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, T. Digital neocolonialism and massive open online courses (MOOCs): Colonial pasts and neoliberal futures. Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joynes, C.; James, Z. An Overview of ICT for Education of Refugees and IDPs. 2018. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/14247 (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Mazari, H.; Baloch, I.; Thinley, S.; Kaye, T.; Perry, F. Learning Continuity in Response to Climate Emergencies: Supporting Learning Continuing Following the 2022 Pakistan Floods; EdTech Hub: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/42XI4RCK/download/4GVHJG2L/Mazari%20et%20al.%20-%202023%20-%20Learning%20continuity%20in%20response%20to%20climate%20emergen.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Horswood, D.; Baker, J.; Fazel, M.; Rees, S.; Heslop, L.; Silove, D. School factors related to the emotional wellbeing and resettlement outcomes of students from refugee backgrounds: Protocol for a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEE. Minimum Standards for Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery; Right to Education Initiative: London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.right-to-education.org/node/301 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Reinhardt, S. Exploring the Emerging Field of Online Tertiary Education for Refugees in Protracted Situations. Open Prax. 2018, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, A. “Education Is Our Weapon for the Future”: Access and Non-Access to Higher Education for Refugees in Nakivale Refugee Settlement, Uganda. Master’s Thesis, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway, 2016. Available online: https://uis.brage.unit.no/uis-xmlui/handle/11250/2415482 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- MacLaren, D. Tertiary Education for Refugees: A Case Study from the Thai-Burma Border. Refug. Can. J. Refug. 2012, 27, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeus, B. Exploring Barriers to Higher Education in Protracted Refugee Situations: The Case of Burmese Refugees in Thailand. J. Refug. Stud. 2011, 24, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.-A.; Plasterer, R. Beyond Basic Education: Exploring Opportunities for Higher Learning in Kenyan Refugee Camps. Refug. Can. J. Refug. 2012, 27, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Tertiary Education. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/what-we-do/build-better-futures/education/tertiary-education (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Yanay, H.; Battle, J. Refugee Higher Education & Participatory Action Research Methods: Lessons Learned From the Field. Radic. Teach. 2021, 120, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Border within: Decolonising Refugee Students’ Education. 28 February 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RjTaAxpaYbM (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Giroux, H.A. On Critical Pedagogy; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinlay, E.; Barney, K. Unknown and Unknowing Possibilities: Transformative Learning, Social Justice, and Decolonising Pedagogy in Indigenous Australian Studies. J. Transform. Educ. 2014, 12, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Agamben’s Theory of Biopower and Immigrants/Refugees/Asylum Seekers: Discourses of Citizenship and the Implications for Curriculum Theorizing. J. Curric. Theor. 2010, 26, 31–45. Available online: https://journal.jctonline.org/index.php/jct/article/view/195 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- From Intentions to Impact: Decolonizing Refugee Response. 27 April 2022. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HLPNF-SbV_M (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Macgilchrist, F. What is “critical” in critical studies of edtech? Three responses. Learn. Media Technol. 2021, 46, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menashy, F.; Zakharia, Z. Private engagement in refugee education and the promise of digital humanitarianism. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2020, 46, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Connected Education for Refugees: Addressing the Digital Divide—World|ReliefWeb. December 2021. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/connected-education-refugees-addressing-digital-divide (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Adam, T. Between Social Justice and Decolonisation: Exploring South African MOOC Designers’ Conceptualisations and Approaches to Addressing Injustices. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burde, D. Humanitarian Action and the Neglect of Education. In Humanitarian Action and the Neglect of Education; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casswell, J. The Digital Lives of Refugees: How Displaced Populations Use Mobile Phones and What Gets in the Way; GSMA: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/The-Digital-Lives-of-Refugees.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Migration Policy Institute. Technology Can Be Transformative for Refugees, but It Can Also Hold Them Back—World|ReliefWeb. 27 July 2023. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/technology-can-be-transformative-refugees-it-can-also-hold-them-back (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Scaife, M.; Rogers, Y.; Aldrich, F.; Davies, M. Designing for or designing with? Informant design for interactive learning environments. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 22–27 March 1997; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, A.F.; Gregor, P. “User sensitive inclusive design”—In search of a new paradigm. In Proceedings of the 2000 Conference on Universal Usability, Arlington, VA, USA, 16–17 November 2000; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Serafy, Y.; Ozegovic, M.; Wagner, E.; Benchiba, S. High, Low, or No Tech? A Roundtable Discussion on the Role of Technology in Refugee Education. Abdulla Al Ghurair Foundation for Education; Save the Children; EdTech Hub: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/high-low-or-no-tech-a-roundtable-discussion-on-the-role-of-technology-in-refugee-education/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Taftaf, R.; Williams, C. Supporting Refugee Distance Education: A Review of the Literature. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2020, 34, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.; Laurillard, D. The Potential of MOOCs for Large-Scale Teacher Professional Development in Contexts of Mass Displacement. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2019, 17, 141–158. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1222894.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Alain, G.; Coughlan, T.; Adams, A.; Yanacopulos, H. A Process for Co-Designing Educational Technology Systems for Refugee Children. In Proceedings of the 32nd International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference (HCI) 2018, Belfast, UK, 4–6 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J. Public-Private Virtual-School Partnerships and Federal Flexibility for Schools during COVID-19, Goldwater Institute, Special Edition Policy Brief. 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3564504 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Bozkurt, A.; Jung, I.; Xiao, J.; Vladimirschi, V.; Schuwer, R.; Egorov, G.; Lambert, S.; Al-Freih, M.; Pete, J.; Olcott, D., Jr.; et al. A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, 1. Available online: http://www.asianjde.org/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/462 (accessed on 7 June 2020).

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 Crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Impact Alliance. Principles for Digital Development. Principles for Digital Development. Available online: https://digitalprinciples.org/privacy-policy/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Selwyn, N. EdTech and Climate Colonialism. Critical Studies of Education & Technology. Available online: https://criticaledtech.com/2022/10/02/edtech-and-climate-colonialism/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Simpson, L.; Carter, A.; Rahman, A.; Plaut, D. Eight Reasons Why EdTech Doesn’t Scale: How Sandboxes Are Designed to Counter the Issue; EdTech Hub: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/8HKCSIRC (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Zoellick, J.C.; Bisht, A. It’s not (all) about efficiency: Powering and organizing technology from a degrowth perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C.E. Rethinking Scale: Moving Beyond Numbers to Deep and Lasting Change. Educ. Res. 2003, 32, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, R.; Gargani, J. Scaling Impact: Innovation for the Public Good|IDRC—International Development Research Centre. Available online: https://www.idrc.ca/en/book/scaling-impact-innovation-public-good (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Krishnan, A. Humanitarian Digital Ethics: A Foresight and Decolonial Governance Approach; Carr Center Discussion Paper Series; Carr Center for Human Rights Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://carrcenter.hks.harvard.edu/publications/humanitarian-digital-ethics (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Jahangir, A.; Khan, F. Challenges to Afghan Refugee Children’s Education in Pakistan: A Human Security Perspective. Pak. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A. Pakistan Faces Inflows of Asylum Seekers from Afghanistan; Anadolu Agency: Ankara, Turkey, 2022; Volume 19, Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/pakistan-faces-inflows-of-asylum-seekers-from-afghanistan/2617186 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- UNHCR. Pakistan Overview of Refugee and Asylum-Seekers Population as of 31 December 2021. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/90452 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- UNHCR. Breaking The Cycle: Education and The Future for Afghan Refugees. Available online: https://adsp.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/R-1_Breaking-the-cycle_-Education-and-future-for-Afghan-Refugees.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Hervé, N. Inclusion of Afghan Refugees in the National Education Systems of Iran and Pakistan. Background Paper Prepared for the 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report “Migration, Displacement and Education: Building Bridges, Not Walls”. UNESCO, ED/GEMR/MRT/2018/P1/7. 2018. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266055 (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Zubairi, A.; Halim, W.; Kaye, T.; Wilson, S. Country-Level Research Review: EdTech in Pakistan; Working Paper; EdTech Hub: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, J.; Bend, M.; Roseo, E.M.; Farrakh, I.; Barone, A. Floods in Pakistan: Human Development at Risk; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/38403 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Tabassum, R.; Hadi, M.; Qaisrani, A.; Shah, Q. Education Technology in the COVID-19 Response in Pakistan. 2020. Available online: https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/TWMVIX77 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- European Union Agency for Asylum. Pakistan, Situation of Afghan Refugees: Country of Origin Information Report; Publications Office: Luxemburg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Final Results (Census-2017)|Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/final-results-census-2017 (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Tamim, T. The politics of languages in education: Issues of access, social participation and inequality in the multilingual context of Pakistan. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 40, 280–299. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24464052 (accessed on 2 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Registered Afghan Refugees in Pakistan. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/pak (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Secondary Education Department, Government of Balochistan. Balochistan Education Sector Plan 2020–2025. Available online: http://emis.gob.pk/Uploads/BESP2020-25.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- UNHCR. Pakistan Factsheet. March 2023. Available online: https://reporting.unhcr.org/pakistan-factsheet-4555 (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Baloch, I.; Taddese, A. EdTech in Pakistan: A Rapid Scan; EdTech Hub: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Khalayleh, A.; Baloch, I.; Kaye, T. Desk Review of Technology-Facilitated Learning in Pakistan: A Review to Guide Future Development of the Technology-Facilitated Learning Space in Pakistan. 2022. Available online: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1F2NuPzMLPDniaM-tQpCZsIKKWYoVpXuyz5-RCUxTR_w/edit (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- UNHCR. Proof of Registration Card (PoR). Available online: https://help.unhcr.org/pakistan/proof-of-registration-card-por/#:~:text=Verification%20of%20PoR%20card,card%20in%20coordination%20with%20NADRA (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- UNHCR. Operation Data: Rwanda. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/rwa (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- UNHCR. Refugees. UNHCR Rwanda. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/rw/who-we-help/refugees (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Rwanda Ministry of Education. Education Sector Strategic Plan 2018/19 to 2023/24. 2019. Available online: https://www.globalpartnership.org/node/document/download?file=document/file/2020-22-Rwanda-ESP.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Government of Rwanda. 7 Years Government Programme: National Strategy for Transformation (NST1). Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/rwa206814.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Kimenyi, E.; Chuang, R.; Taddese, A. EdTech in Rwanda: A Rapid Scan; EdTech Hub: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Available online: https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/TYBTWI8K (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Rwanda Ministry of ICT and Innovation. Smart Rwanda 2020 Master Plan. 2015. Available online: https://minict.gov.rw/fileadmin/Documents/Strategy/SMART_RWANDA_MASTER_PLAN_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Ministry Of Information Technology And Communications. ICT Sector Strategic Plan (2018–2024) “Towards Digital Enabled Economy”; Ministry of Information Technology and Communications: Kigali, Rwanda, 2017. Available online: https://www.minict.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/minict_user_upload/Documents/Policies/ICT_SECTOR_PLAN_18-24_.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- UNHCR. Help: Rwanda: Online Learning Opportunities. UNHCR Rwanda. Available online: https://help.unhcr.org/rwanda/services/education/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Dryden-Peterson, S.; Adelman, E.; Bellino, M.J.; Chopra, V. The Purposes of Refugee Education: Policy and Practice of Including Refugees in National Education Systems. Sociol. Educ. 2019, 92, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Rwanda, Ministry in Charge of Emergency Management and UNHCR. The Ministry in Charge of Emergency Management (Minema) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Joint Strategy on Economic Inclusion of Refugees and Host Communities in Rwanda. 2021. Available online: https://www.minema.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/Minema/Publications/Laws_and_Policies/MINEMA-UNHCR_Joint_Strategy_of_economic_inclusion_of_refugees_and_host_communities_2021-2024.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Ethnologue. Rwanda. Ethnologue (Free All). Available online: https://www.ethnologue.com/country/RW/ (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- UNICEF. The Impact of Language Policy and Practice on Children’s Learning: Evidence from Eastern and Southern Africa—Rwanda. 2017. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/esa/sites/unicef.org.esa/files/2018-09/UNICEF-2017-Language-and-Learning-Rwanda.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Kazak, C. Ethics in forced migration research: Taking stock and potential ways forward. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 2021, 9, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.; Warr, D.; Gibbs, L.; Riggs, E. Addressing ethical and methodological challenges in research with refugee-background young people: Reflections from the field. J. Refug. Stud. 2013, 26, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; McKee, K.; McCoughlin, P. Online focus groups and qualitative research in the social sciences: Their merits and limitations in a study of housing and youth. People Place Policy Online 2015, 9, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodyatt, C.R.; Finneran, C.A.; Stephenson, R. In-Person Versus Online Focus Group Discussions: A Comparative Analysis of Data Quality. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, S.C.; Buckle, L.J. The Space between: On Being an Insider-Outsider in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwasser, P. Exploring internalized oppression and healing strategies. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2002, 2002, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Nicol, C.; Maalim, S.; Olow, M.; Ali, A.; Nashon, S.; Bulle, M.; Hussein, A.; Hussein, A. Crossing Borders: A Story of Refugee Education. In Internationalizing Curriculum Studies; Hébert, C., Ng-A-Fook, N., Ibrahim, A., Smith, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Displaced Person. Available online: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/networks/european-migration-network-emn/emn-asylum-and-migration-glossary/glossary/displaced-person_en (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Dados, N.; Connell, R. The Global South. Contexts 2012, 11, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups—World Bank Data Help Desk. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- United Nations. Youth: Who Are the Youth? Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Elementary and Secondary Education Department. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Education Sector Plan 2020–2025. Available online: https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/pakistan-khyber-pakhtunkhwa-esp.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2023).

| Dimensions of Human Injustice Aspects | Research and Analysis Questions in the Context of Lived Refugee Experiences in Pakistan and Rwanda |

| Material Injustices |

|

| |

| |

| Cultural–epistemic injustices |

|

| |

| Political and geopolitical injustices |

|

| |

| |

|

| Focus Group Discussion | Location | Number of Participants | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pakistan | 8 | Female |

| 2 | Pakistan | 6 | Male |

| 3 | Rwanda | 6 | Mixed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnes, K.; Emerusenge, A.P.; Rabi, A.; Ullah, N.; Mazari, H.; Moustafa, N.; Thakrar, J.; Zhao, A.; Koomar, S. Designing for Social Justice: A Decolonial Exploration of How to Develop EdTech for Refugees. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010077

Barnes K, Emerusenge AP, Rabi A, Ullah N, Mazari H, Moustafa N, Thakrar J, Zhao A, Koomar S. Designing for Social Justice: A Decolonial Exploration of How to Develop EdTech for Refugees. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnes, Katrina, Aime Parfait Emerusenge, Asma Rabi, Noor Ullah, Haani Mazari, Nariman Moustafa, Jayshree Thakrar, Annette Zhao, and Saalim Koomar. 2024. "Designing for Social Justice: A Decolonial Exploration of How to Develop EdTech for Refugees" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010077

APA StyleBarnes, K., Emerusenge, A. P., Rabi, A., Ullah, N., Mazari, H., Moustafa, N., Thakrar, J., Zhao, A., & Koomar, S. (2024). Designing for Social Justice: A Decolonial Exploration of How to Develop EdTech for Refugees. Education Sciences, 14(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010077