Shaping Entrepreneurial Attitudes among Young Children on the Basis of the “Entrepreneurial Kids” International Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Personality approach according to which entrepreneurship is something you are born with.

- Economic stream which focuses on analyzing the role of entrepreneurs in the widely understood economy.

- Sociological and anthropological concept which is derived from the belief that entrepreneurship, in its broadest sense, is a social phenomenon; therefore, it is important to collect as much data as possible on companies and the individuals working in them, taking into account the social context.

- Behavioral theories defining entrepreneurial attributes [1].

2. Entrepreneurship in the Source Literature

- “Ideas and possibilities”: seeing possibilities, creativity, visioning, evaluating ideas (ideas), ethics, and “balanced’ thinking”.

- “Resources”: self-awareness and self-efficacy, motivation and perseverance, mobilizing resources (obtaining and managing resources), competence related to financial and economic knowledge, mobilizing others.

- “Action”: taking initiative, planning and managing, dealing with ambiguity, uncertainty, and risk, ability to work with others (team collaboration), and continuous learning through experience.

3. Kids’ Entrepreneurship in Practice—The Entrepreneurial Kids Project

3.1. Theoretical Background

3.2. Schedule of Activities

- present Lublin’s economic potential, with a focus on its potential for use in education-related activities.

- provide information on project implementation to school/preschool staff and students.

3.3. Internationalization

- (a)

- Topics and sequence of activities remained unchanged

- (b)

- The teacher in charge of the class received a set of materials to work with the children, examples of products that are manufactured by companies in Lublin, and a short video of a recorded visit to one of the companies located in Lublin

- (c)

- During the third workshop, the children worked not only with a map of Lublin but also with a map of Oxford on which they searched for their parents’ places of employment

- (d)

- During the project, the children had an online meeting with colleagues from Poland where they were able to present the companies they had set up

- (e)

- Steps were taken to allow pupils from Oxford to join the gala remotely. For technical reasons, this proved impossible, but the children from abroad prepared a short recording, which was broadcast during the gala.

4. Summary

- Increased awareness of an interdisciplinary understanding of the concept of entrepreneurship among pupils, teachers, students, and entrepreneurs.

- Increased interest in entrepreneurial education among parents and teachers working in preschools and primary schools.

- Development of the possibility of a targeted and evaluable plan for cooperation between the business sector and education, and through this, creating space for the economy to have a real impact on the level of education.

- Improvements in the quality of primary education by introducing a new modus operandi to establishments in Lublin, which targets young children and integrates the aims and tasks of shaping in them one of the key competencies—entrepreneurship.

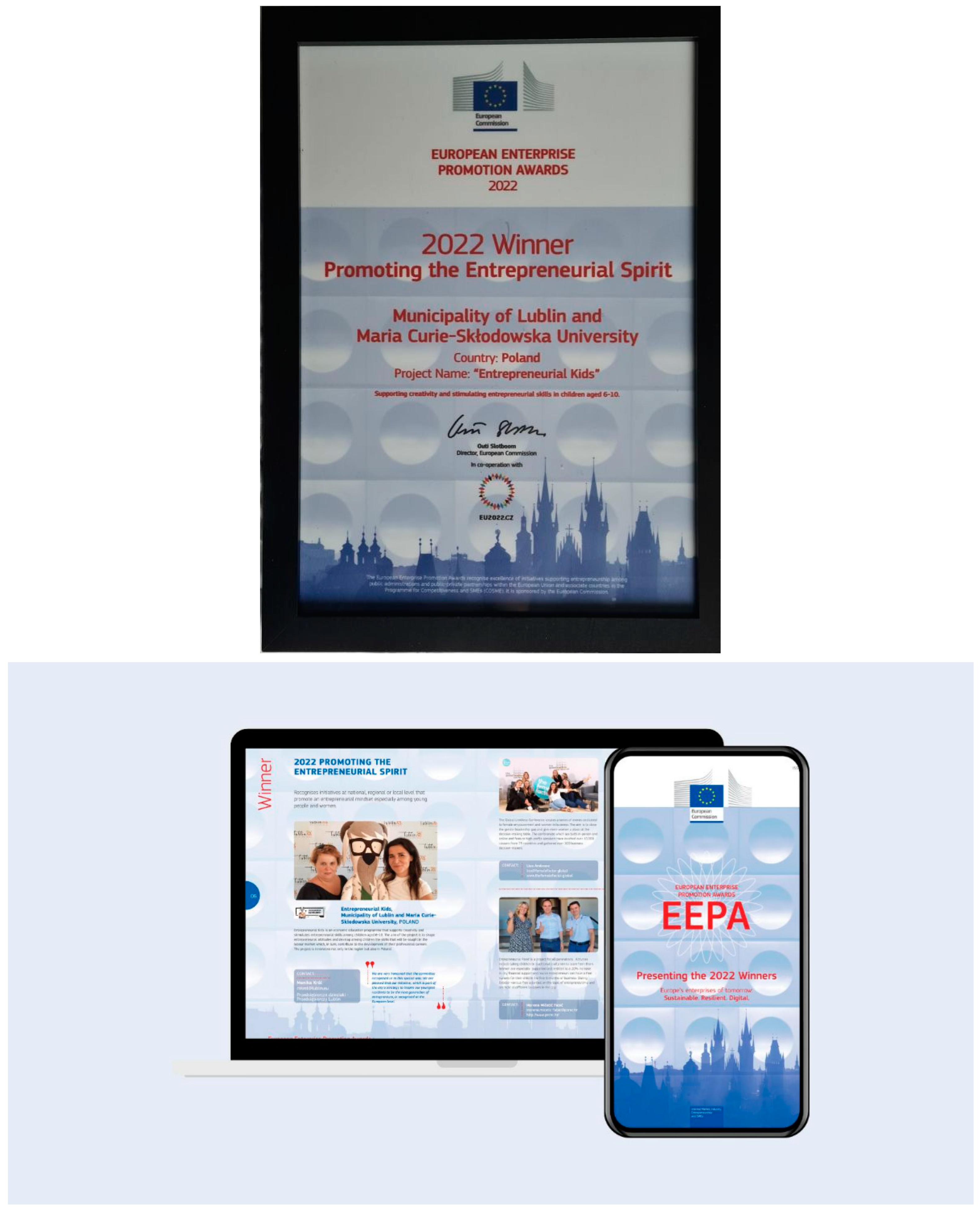

- Promotion of the economic potential and positive image of Lublin as a city that creates favorable conditions for cooperation between the local government sector, economy, and higher education.

- Promotion of the Maria Curie-Sklodowska University as a leading scientific center for cooperation with the socio-economic environment and the creation of innovative interdepartmental solutions for the development of key competencies and as a university that offers students practical classes in social studies concerning entrepreneurship and the promotion of career opportunities in Lublin or its vicinity (shaping attitudes of local patriotism).

- Promotion of Poland on the international stage among business audiences (with a real impact on the European economy) as a country where entrepreneurship is promoted in an exemplary (worthwhile and implementable) manner.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rachwał, T. Entrepreneurship as a Key Competence in Education System. FRSE 2021. Available online: https://www.frse.org.pl/storage/brepo/panel_repo_files/2021/06/01/iacgqo/104705065591760-16-34.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- European Council Recommendation of 22 May 2018 on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning, (2018/C 189/01); European Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning, (2006/962/WE). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2006/962/oj (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Rusu, S.; Isac, F.; Cureteanu, R.; Csorba, L. Entrepreneurship and entrepreneur: A review of literature concepts. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 3570–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.; Thurik, R. Understanding the role of entrepreneurship for economic growth. Entrep. Econ. 2006, 134, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, C.; Friis, C.; Paulsson, T. Relating entrepreneurship to economic growth. In The Emerging Digital Economy: Entrepreneurship Clusters and Policy; CESIS/JIBS Electronic Working Paper Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Paper No. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Vlăsceanu, M. Economie Socială şi Antreprenoriat; Polirom Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, N.M. What Brings Entrepreneurial Success in a Developing Region? J. Entrep. 2000, 9, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A.; Henry, R.A. How Entrepreneurs Acquire the Capacity to Excel: Insights from Research on Expert Performance. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2010, 4, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, J.; Page, S. Tourism and Entrepreneurship: International Perspectives (Advances in Tourism Research); Elsevier: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Piti, M. Antreprenor “Made in Romania”. 2010. Available online: http://www.postprivatizare.ro/romana/antreprenor-made-in-romania/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Cardella, G.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Sánchez García, J.C. Entrepreneurship and Family Role: A Systematic Review of a Growing Research. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banha, F.; Coelho, L.S.; Flores, A. Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Identification of an Existing Gap in the Field. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, E.; Gonzalez, I.; Iriarte, I.; Beitia, A.; Lasa, G.; Elkoro, M. A Design Thinking approach to introduce entrepreneurship education in European school curricula. Des. J. 2017, 20, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackéus, M. Entrepreneurship in Education—What, Why, When, How; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Canal, M.; Sanz Ponce, R.; Azqueta, A.; Montoro-Fernández, E. How Effective Is Entrepreneurship Education in Schools? An Empirical Study of the New Curriculum in Spain. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A. Entrepreneurship Education—Status Quo and Prospective Developments. J. Entrep. Educ. 2013, 16, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A. What’s Hot in Entrepreneurship Research in 2013? Universität Hohenheim: Stuttgart, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kourilsky, M.L.; Rapp, S.; Carlson, C. Mini-Society and Yess! Learning Theory in Action. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 1996, 1, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L.H.; Sloof, R.; van Praag, M. The Effect of Early Entrepreneurship Education: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2014, 72, 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, M.; Marszałek, P.; Warchlewska, A. Mapa Edukacji Finansowej, 6th ed.; ZBP: Poznań, Poland, 2019; Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hassi, A. Effectiveness of early entrepreneurship education at the primary school level: Evidence from a field research in Morocco Citizenship. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2016, 15, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundry, L.K.; Ofstein, L.F.; Kickul, J.R. Seeing around corners: How creativity skills in entrepreneurship education influence innovation in business. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Cheng, L.; Niu, W.; Tong, Z. How parenting styles affect children’s creativity: Through the lens of self. Think. Ski. Creat. 2022, 45, 101045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupers, E.; Lehmann-Wermser, A.; McPherson, G.; van Geert, P. Children’s Creativity: A Theoretical Framework and Systematic Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 89, 93–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryazeva-Dobshinskaya, V.G.; Dmitrieva, Y.A.; Korobova, S.Y.; Glukhova, V.A. Children’s Creativity and Personal Adaptation Resources. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potters, O.T.A.; van Schijndel, T.J.P.; Jak, S.; Voogt, J.M. Two decades of research on children’s creativity development during primary education in relation to task characteristics. Educ. Res. Rev. 2023, 39, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondracka-Szala, M.; Malinowska, J. Entrepreneurship Education as a Challenge in the Education of Teachers of Pre-school and Early School Children—At the Intersection of Academic Theory and Practice. New Educ. Rev. 2019, 58, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wygotski, L.S. Narzędzie i Znak w Rozwoju Dziecka; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wygotski, L.S. Wybrane Prace Psychologiczne II. Dzieciństwo i Dorastanie; Zysk i S-ka: Poznań, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B. The Montessori Method and the Neurosequential Model in Education (NME): A comparative study. J. Montessori Res. 2022, 8, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeanah, C.H.; Gunnar, M.R.; McCall, R.B.; Kreppner, J.M.; Fox, N.A. Sensitive Periods. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2011, 76, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, B.C.; Bloch, N. Learning by Doing. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Seel, N.M., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasen, P. Culture and cognitive development from a Piagetian perspective. In Psychology and Culture; Lonner, W.J., Malpass, R.S., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, C.; Grafe, N.; Hiemisch, A. Associations of media use and early childhood development: Cross-sectional findings from the LIFE Child study. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 91, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider-Cios, E.; Vermeij, A.; Sitskoorn, M.M. Young children and screen-based media: The impact on cognitive and socioemotional development and the importance of parental mediation. Cogn. Dev. 2023, 66, 101319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.K.; Ho, Y.P.; Autio, E. Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Economic Growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A.A. The future of entrepreneurship education—Determining the Basis for Coherent Policy and Practice. In The Dynamics of Learning Entrepreneurship in a Cross Cultural University Context; Kryo, P., Carrier, C., Eds.; Research Centre for Vocational and Professional Education, University of Tampere: Tampere, Finland, 2005; pp. 44–68. [Google Scholar]

| Title of Project/Program | Age of Participants | Organizer |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship. “How to turn an idea into reality?” | Years 2–3 of primary school | Children’s University Foundation |

| From Polish grosz to Zloty | Years 2–3 of primary school | Foundation for Youth Entrepreneurship |

| School Savings Banks | Years 1–8 of primary school | PKO BP |

| Open Company Programme | Years 1–8 of primary school | Foundation for Youth Entrepreneurship |

| ABC Economics programme (children’s story book) | Younger years of primary school | Czepliński Family Foundation |

| TelantowiSKO programme | Years 1–8 of primary school | Co-operative Banks |

| I think, I decide, I act—finance for children | Years 1–3 of primary school | Association for the Promotion of Financial Education |

| Finansiaki | Preschool and primary school | Bank Santander |

| Financial primer | Preschool | Bank Millennium |

| Element/Stage of the Project | January | February | March | April | May | June |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preparation | - Division of tasks in the team - Drawing up documentation - Project promotion | |||||

| Promotion | Promotion on social media, in local media, submitting project to competitions | |||||

| Recruitment | - Recruitment information on websites - Acceptance of applications (due date after winter holidays; duration: two weeks for the first edition, one week for subsequent editions) | |||||

| Information meeting | Approx. 2 weeks after announcement of recruitment results | |||||

| Workshops | There should be an interval of one week between the first, second and third workshops. The fourth workshop is conducted after visits to the company and a meeting with the creative person. | |||||

| “Class company” project work | The company is set up at the last workshop with the student. Further stages up to the fulfilment of the target are carried out by the teacher in May (one month is enough time to get the expected results). | |||||

| Company visits | Workshops are performed in collaboration with large local companies and within their premises. Each group attends one. | |||||

| Meetings with creative people | Workshops performed in the educational institution or workplace of a representative of the creative professions. | |||||

| Visit to a bank | Visit to a bank can be performed independently of the other elements of the project. | |||||

| Gala | Project closing ceremony | |||||

| Summary | Archiving of documentation, evaluation studies, preparation of reports. | |||||

| Workshop Topic | Objectives | Task to be Completed at Home with Parents |

|---|---|---|

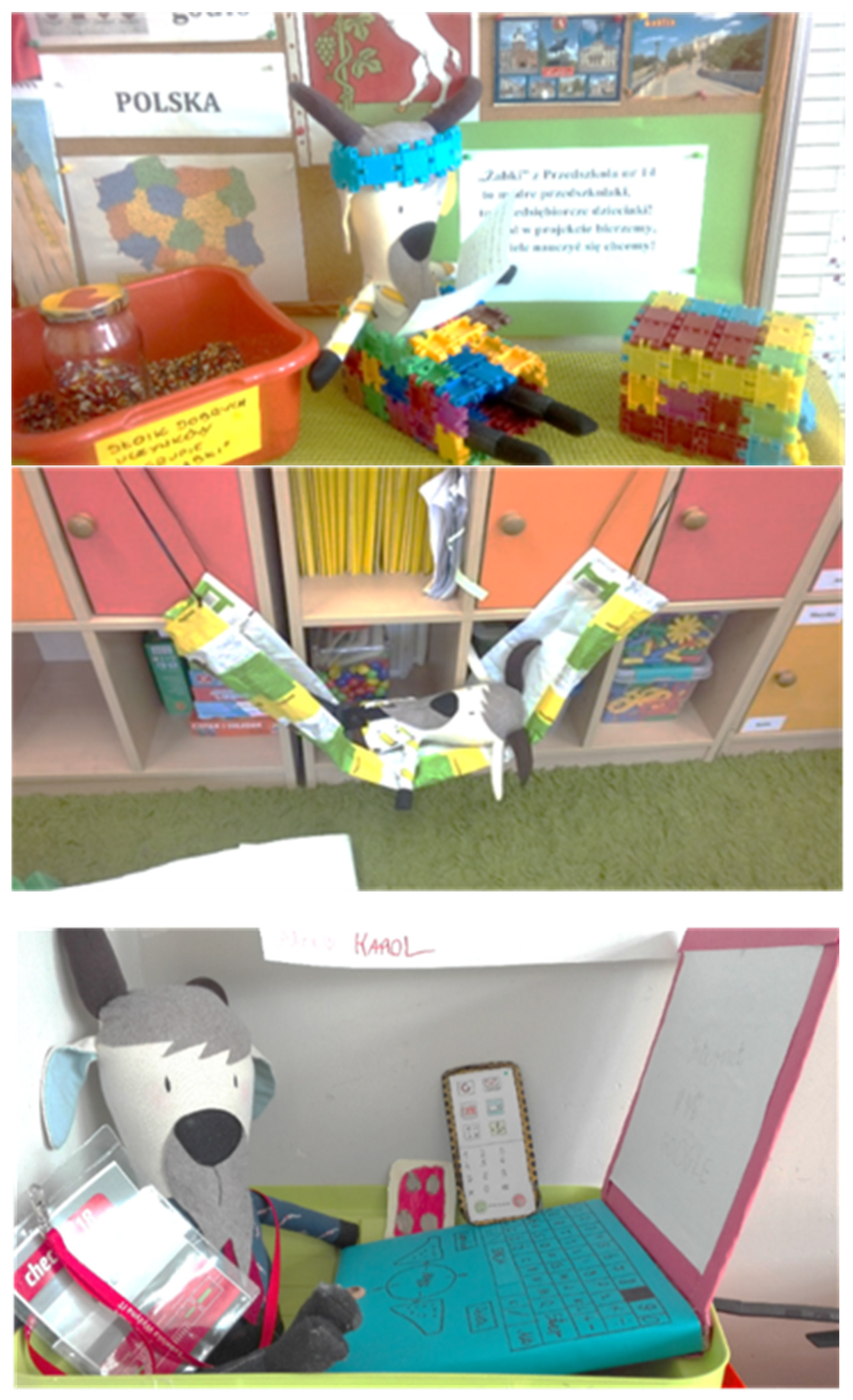

| Workshop no. 1 Let’s get to know each other | - Familiarization with the project themes and objectives - Integration of children with a little goat - Preparing a contract (agreement) between the children and the little goat - Preparing a creative corner for a little goat | The children give their parents envelopes with information about the project and a request to prepare a “signature” (photograph, handprint) to be attached to the contract prepared by the children. In this way, the parents are involved and informed about the activities and their objectives. During the following week, the children bring the so-called “rubbish” (clean, not smelly, safe to use unnecessary materials) to the little goat’s corner. |

| Workshop no. 2 Entrepreneurship—the difficult word | - Introducing the notion of entrepreneurship, understood among other things as creativity - Developing fine motor skills and social skills by making toys from unwanted items brought in - Building children’s self-esteem by showing that anyone can be creative because anyone can make “something out of nothing” - Shaping an active attitude toward entrepreneurship as a trait to be discovered and developed | The homework consists of preparing a few-minute presentation with the parent (perhaps a talent, a toy, a hobby, or a favorite book). The parent is also given a short briefing on how to help the child in a stressful situation. |

| Workshop no. 3 Everyone can be an entrepreneur | ||

| Part one: Talent show | - Practicing presentation skills and coping with stress -Building self-confidence by creating a successful situation for each child - Integrating the class/group by getting to know its members better | The presentation is organized by the teacher. They can invite parents, other groups from the preschool or school. It is possible to organize the “show” only with the group/class. However, this is the least effective way to achieve the intended goals. It is important that the teacher ensures that every child performs and that each child receives positive feedback (applause, praise from the teacher and possibly parents). |

Part two: Secrets of economic Lublin | - Introduction of concepts related to running a company (logo, business plan, marketing) - Getting to know companies and representatives of the creative sector based in Lublin (learning about the economic potential of Lublin) - Promoting Lublin as a strong brand | Prepare information with the parents about the company and the creative person the class/group will meet. |

| Workshop 4. Starting your own business | - Shaping the skills of teamwork (through the children setting up their own business), planning (through the preparation of a business plan), and the consistent implementation of plans - Fostering creativity - Consolidation of the information obtained during the workshop. | Parents receive information from the teacher about the class company the children have set up and the goal they have chosen (it is important that parents agree to the goal). It is important to get parental support for the company’s fundraising (e.g., participation in a fair organized by the children). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chojak, M. Shaping Entrepreneurial Attitudes among Young Children on the Basis of the “Entrepreneurial Kids” International Project. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010074

Chojak M. Shaping Entrepreneurial Attitudes among Young Children on the Basis of the “Entrepreneurial Kids” International Project. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleChojak, Małgorzata. 2024. "Shaping Entrepreneurial Attitudes among Young Children on the Basis of the “Entrepreneurial Kids” International Project" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010074

APA StyleChojak, M. (2024). Shaping Entrepreneurial Attitudes among Young Children on the Basis of the “Entrepreneurial Kids” International Project. Education Sciences, 14(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010074