Abstract

The current study examines the relationship between digital competencies and collaboration attitudes among higher education students. To do so, data from 1316 students from 10 Spanish universities were analyzed and collected through a questionnaire named “Basic Digital Skills 2.0 of University Students” (COBADI®—Registered Trademark: 2970648). To provide context for the sample involved in this study, it is noteworthy that 50.5% of participants typically prefer to access the internet from home. Furthermore, it was observed that most of the respondents engage with the internet for over nine hours daily. The analysis of the results was conducted by calculating correlations between digital competencies and students’ collaboration attitudes. These correlations were computed using the Python programming language, with the libraries employed being pandas, numpy, and matplotlib. Students who perceive themselves as more competent in using digital tools tend to have a slightly higher disposition to collaborate with their professors in virtual environments. Some competencies are more closely associated with collaboration than others, with those that exhibit a stronger connection being key focus areas in teaching and curriculum development.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the importance of information and communications technologies (ICT)-related skills in the process of modern and effective teaching has been highlighted in the scientific literature [1,2,3].

Likewise, digital integration in research activities will enable the continuous updating and expansion of knowledge through faster and more accessible access to digital information than in previous years [4]. The advent of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic has prompted higher education institutions to invest efforts in incorporating digital technologies into their curricular programs and classrooms, which traditionally operated face-to-face [5].

In the scientific literature, various terms identify digital competence; however, in line with [6], it can be considered a form of multiple and complex literacy that integrates values, beliefs, knowledge, skills, and attitudes in the technological, informational, and communicative domains. In 2018, the European Commission determined that it can also be understood as one of the basic competencies for lifelong learning, involving the safe, critical, and responsible use of digital technologies in academic, professional, and social contexts (European Commission 2018).

In recent years, research on digital competence has gained significant importance in the field of Educational Technology, both for educators and students in higher education [7]. The European DIGCOMP framework of the European Economic Community [8] encompasses areas such as information, communication, content creation, security, and problem-solving. This framework has recently been updated in its DIGCOMP 2.2 version to define assessment levels [9]. Consequently, it can be inferred that modern societies and educational institutions demand a shift in competency focus so that tomorrow’s citizens acquire the skills and abilities to navigate a complex, technological, competitive, and ever-changing job market.

Recent research reveals varied digital competencies among university students, with strengths and areas needing improvement. The author of [10] notes that these competencies differ based on gender, class, and academic achievement, showing both high and moderate dimensions. The authors of [11] find that graduate students often employ information and communication technology (ICT) traditionally, influenced by gender and age. The authors of [12] report a positive outlook on digital competencies, especially in information and data literacy, but underscore the need for more training, particularly for female and rural students. The findings of [13] complement this, revealing that university and high-school students self-assess their digital skills as below intermediate, with programming as a weak point. The authors of [14], on one hand, highlight the value academics place on students’ digital competences for learning, while [15] points out the lack of a systematic process for developing these competencies in university environments, suggesting the need for a new strategic approach.

In addition, effective collaboration in educational settings, emphasized by various researchers [16,17,18], not only enriches the overall learning experience but also contributes to heightened individual learning outcomes and increased student satisfaction. Beyond academic achievements, collaborative learning fosters a sense of community, belonging, and influence among students [19]. Additionally, as explored by [20], it plays a pivotal role in maintaining emotional support and serves as a valuable indicator of both individual student progress and group dynamics [21]. In a parallel vein, the influence of social networks as relationship contexts and content repositories as collaboration spaces is evident in the development of creativity among users [22]. Recognizing the significance of interaction, both among students and between students and teachers, is essential to grasp the intricate nature of the collaborative learning process [20].

Collaboration has a significant positive correlation with the development of digital skills, both directly and indirectly [23]. This is particularly evident in the use of digital technologies for teacher collaboration, which can enhance both teachers’ and students’ digital competence [24]. The level of digital skills also influences students’ attitudes towards collaborative online learning [25]. Furthermore, a collaborative approach to developing teachers’ digital skills, including the selection and use of digital tools, has been found to be effective [26].

Taking into account the ideas previously discussed, the aim of this article is to analyze the correlation between the development of digital competencies in university students and their collaboration attitudes in academic scenarios.

2. Methodology

The research design is non-experimental, aiming to describe the relationships between aspects without direct manipulation [27].

The data used for the study were obtained through the application of the questionnaire instrument “Basic Digital Skills 2.0 of University Students—COBADI®”, with a registered trademark: 2970648. This is a self-perception questionnaire for digital competencies, implemented virtually through the following link: https://bit.ly/2p1aKVh (accessed on 27 April 2023).

The questionnaire was distributed through a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method. The questions were related to basic digital competencies, specifically consisting of 23 items distributed across three categories. The first category pertains to “Competencies in the use of ICT for searching and processing information,” referring to individual competence in using various technological tools, the module analyzed in this research. This module consists of 11 items assessed through a Likert scale of 1–4 points, where 1 indicates, “I feel completely ineffective in performing what is presented” and 4 denotes, “I feel completely effective.” Additionally, it includes the option NS/NC/NA (if you are not sure about the response or if it is not applicable to the question asked). The second category, “Interpersonal Competencies in the use of ICT in university settings,” with 8 items, evaluates how a student resolves doubts and problems related to ICT. The third category, “Virtual Tools and Social Communication at the University,” includes questions about students’ use of the university’s electronic platforms.

In the applied instrument, all questions were mandatory, and no personal data were collected, ensuring complete anonymity, as stated above. The questionnaire was previously validated in [28]. The instrument was available from 2013 to 2022 and was completed by 1316 students from various Spanish universities, specifically originating from the following institutions: the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the Complutense University of Madrid, the University of Huelva, the Catholic University of Ávila, the University of Granada, the University of Oviedo, the Polytechnic University of Valencia, the Higher Polytechnic School of Granada, the University of Alicante, and Pablo de Olavide University.

The data were gathered through a questionnaire entitled “Basic Digital Skills 2.0 of University Students” COBADI® (Registered Trademark: 2970648). The aim of this questionnaire is to assess the 2.0 digital skills of university students. This survey was developed and tested by members of the EDUINNOVAGOGÍA® (HUM-971) research group, recognized by the Andalusian Plan for Research, Development, and Innovation, and the Research Results Transfer Office at Pablo de Olavide University (UPO) in Seville, Spain. It has been utilized in both European Higher Education Area countries and in Latin American countries, such as Mexico and Colombia [29,30].

The approach used in this study is quantitative, with a non-experimental cross-sectional design and a descriptive-correlational scope. The two analyzed variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of the variables.

The two variables were assessed using the COBADI questionnaire, which comprises self-perception items. It was completed by 1316 students from various universities: the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the Complutense University of Madrid, the University of Huelva, the Catholic University of Ávila, the University of Granada, the University of Oviedo, the Polytechnic University of Valencia, the Higher Polytechnic School of Granada, the University of Alicante, and Pablo de Olavide University.

The competency variables analyzed were:

- A1: I can communicate with others via email;

- A2: I use Chat to interact with others;

- A3: I use instant messaging as a communication tool with others;

- A4: I can communicate with others by participating in social networks;

- A5: I am capable of operating in professional networks;

- A6: I can participate appropriately in forums;

- A7: I consider myself competent to participate in blogs;

- A8: I know how to design, create, and modify blogs or weblogs;

- A9: I know how to use wikis;

- A10: I consider myself competent to design, create, or modify a wiki;

- A11: I use the syndication system;

- A12: I know how to use social bookmarks, tagging, “social bookmarking”;

- A13: I am capable of using educational platforms;

- A14: I can navigate the Internet using different browsers;

- A15: I am capable of using different search engines;

- A16: I feel competent to work with some digital mapping program to find places;

- A17: I know how to use programs to plan my study time;

- A18: I work with documents on the network;

- A19: I am capable of organizing, analyzing, and synthesizing information through concept maps using some social software tool;

- A20: I can use programs to disseminate interactive presentations online;

- A21: I feel competent to work with social software tools that help me analyze and/or navigate through content included in blogs;

- A22: I work with images using social software tools and/or applications;

- A23: I feel capable of using podcasting and videocasts;

- A24: I use QR codes to disseminate information.

Considering the above, correlation calculations were carried out by cross-referencing the listed competencies with students’ collaboration attitudes (with teachers and peers). The scale for interpreting the results is presented in Table 2. The correlation calculations were carried out using the Python programming language, and the libraries used were pandas, numpy, and matplotlib.pyplot. The codes used in the Google Colab tool are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Values and interpretation of the correlation.

Table 3.

Code written in Python and used in Google Colab.

The following question guided this study: What is the correlation between the development of digital competencies in university students and their attitudes towards collaboration in academic scenarios? Within the framework of this question, two hypotheses were defined:

- H_1: There is a strong correlation between the development of digital competencies in university students and their attitudes towards collaboration in academic scenarios. This is due to the contributions of Saputra, 2021; Muñoz, 2021; Kwiatkowska, 2022; and Yooyativong, 2018.

- ○

- H0_1: There is no correlation between the development of digital competencies in university students and their attitudes towards collaboration in academic scenarios.

- H_2: The correlation of attitudes towards collaboration is stronger with competencies A1, A2, A3, and A4. These competencies have been specifically selected due to their direct orientation towards facilitating actions in communication.

- ○

- H0_2: There is no significant difference between the correlation of the attitudes towards collaboration with the 24 digital competencies.

3. Results

The results were analyzed based on the population characterization and the study related to the correlation analysis between the development of digital competencies and students’ collaboration attitudes.

Regarding the population characterization, more than half of the surveyed population fell within the age range of 18–20 years (66%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number and percentage of students, by age range.

3.1. Population Characterization

The surveyed students belong to the educational field of Social Sciences, especially in the Bachelor’s degrees in Social Education (38.4%) and Double Bachelor’s degrees in Social Education and Social Work (31.2%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Number and percentage of the degree pursued by those who responded to the questionnaire.

Regarding the usual location for internet connection, more than half (50.5%) of the respondents prefer to connect at home, or, alternatively, anywhere using a mobile device (46.4%) (Table 6). In this regard, the study aligns with a study conducted on teacher education students in Uruguay [31], where, for several activities, mobile usage was preferred to the laptop distributed for free under the educational policy. Additionally, other research studies [28,32,33,34] demonstrate students’ interest and motivation in using mobile devices in educational settings and their implications for students’ learning outcomes.

Table 6.

Most common location to connect to the internet.

Ultimately, it is noted that more than half of the respondents frequently use the internet (over 9 h per day) (Table 7). In this regard, the study aligns with the research by [35], which indicated that 50% of the university population connected to the internet every day, mainly for chatting (76.4%), downloading movies and music (52%), and studying (32.6%). Similarly, a survey conducted in 2018 by the Association for Media Research [36] on Spanish internet users identified that users over the age of fourteen primarily use mobile phones to access the internet, with over 40% spending more than 4 h online daily.

Table 7.

Dedication to browsing the internet during the week, by range of hours per week.

3.2. Correlation Analysis

In this section, the correlation between two variables is presented: (1) development of digital competencies and (2) collaboration attitude of the students. The outcomes are divided and presented in accordance with the two hypotheses formulated earlier.

3.2.1. H1: There Is a Strong Correlation between the Development of Digital Competencies in University Students and Their Attitudes towards Collaboration in Academic Scenarios

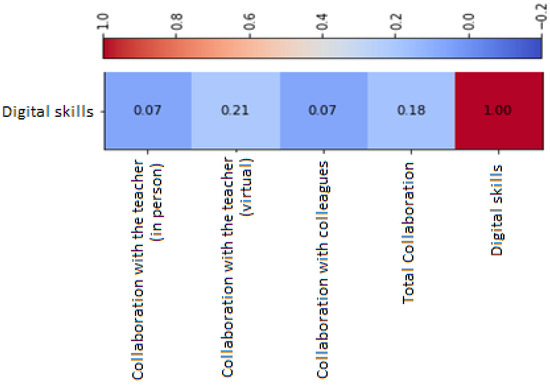

Figure 1 shows the correlation of the total skills versus collaboration in a heatmap. Table 8 presents the complete correlation matrix for each of the 24 skills and collaboration. The following figures display heatmaps of the correlations for the seven skills that exhibited the highest values.

Figure 1.

Correlation between the development of digital competencies and student collaboration attitude.

Table 8.

Correlation matrix.

In Figure 1, it is evident that there is a weak correlation between the development of digital competencies and virtual collaboration with the teacher. Conversely, there is no correlation between the development of digital competencies and collaboration with peers or in-person collaboration with the teacher.

In Table 8, on the other hand, it is observed that the correlations are either null or weak. In the specific case of the correlation between digital competencies and in-person collaboration with the teacher, all results indicate that there is no such correlation. Meanwhile, virtual collaboration with the teacher more frequently shows a weak correlation with digital competencies.

3.2.2. H2: The Correlation of Attitudes towards Collaboration Is Stronger with Competencies A1, A2, A3, and A4

The highest correlations obtained in this study are presented between collaboration and the following competencies:

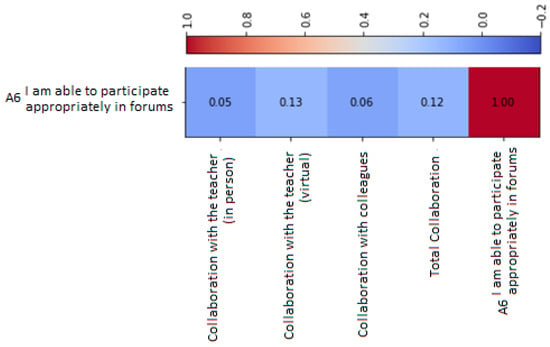

- A6: I am able to participate appropriately in forums (Figure 2);

Figure 2. Correlation between skill A6 and collaboration.

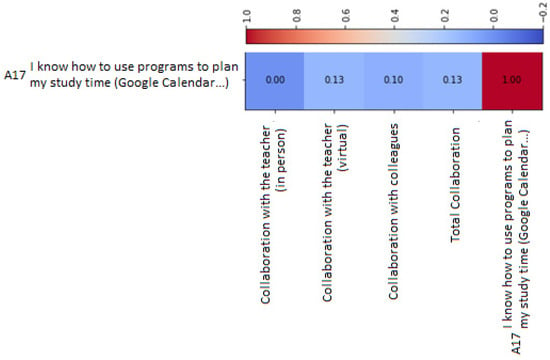

Figure 2. Correlation between skill A6 and collaboration. - A17: I know how to use programs to plan my study time (Figure 3);

Figure 3. Correlation between skill A17 and collaboration.

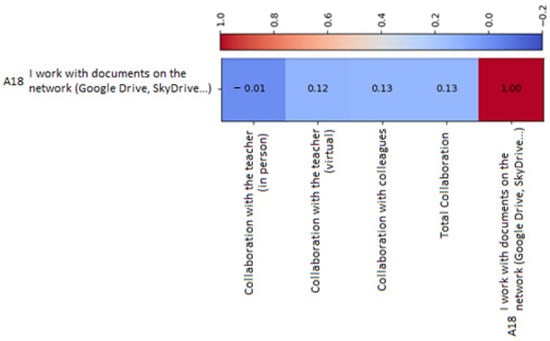

Figure 3. Correlation between skill A17 and collaboration. - A18: I work with documents on the network (Figure 4);

Figure 4. Correlation between skill A18 and collaboration.

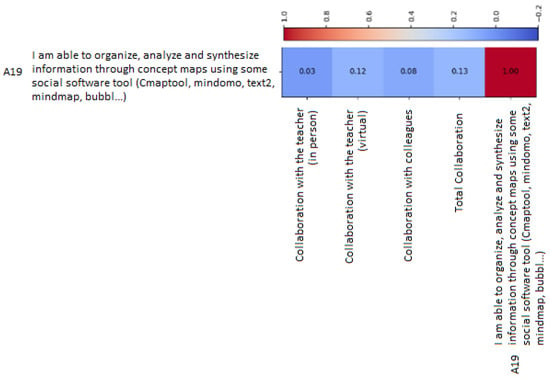

Figure 4. Correlation between skill A18 and collaboration. - A19: I am able to organize, analyze, and synthesize information using concept maps with some social software tool (Figure 5);

Figure 5. Correlation between skill A19 and collaboration.

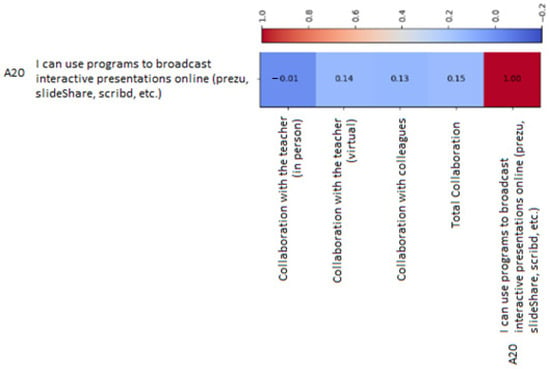

Figure 5. Correlation between skill A19 and collaboration. - A20: I can use programs to disseminate interactive presentations online (Figure 6);

Figure 6. Correlation between skill A20 and collaboration.

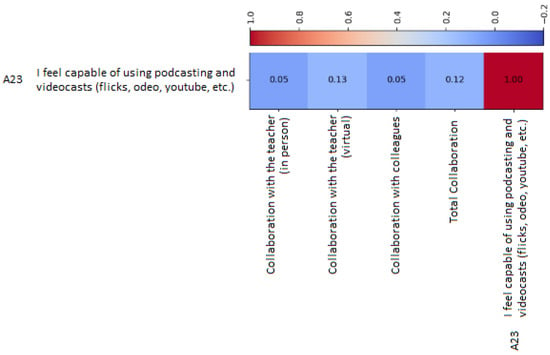

Figure 6. Correlation between skill A20 and collaboration. - A23: I feel capable of using podcasting and videocasts (Figure 7);

Figure 7. Correlation between skill A23 and collaboration.

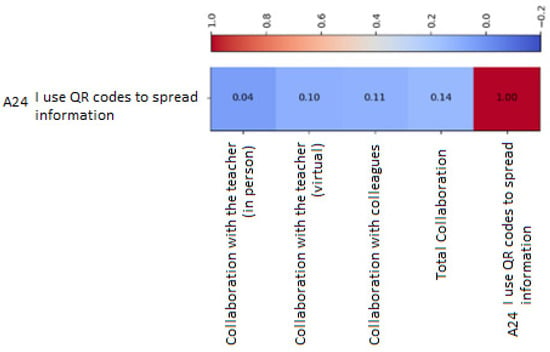

Figure 7. Correlation between skill A23 and collaboration. - A24: I use QR codes to disseminate information (Figure 8);

Figure 8. Correlation between skill A24 and collaboration.

Figure 8. Correlation between skill A24 and collaboration. - The competency that has the strongest correlation with collaboration is A20—I can use programs to disseminate interactive presentations online (Prezi, SlideShare, Scribd, etc.), followed by A24: I use QR codes to disseminate information.

The forums mentioned in Figure 2 refer to those offered on academic platforms but also on sites like mass media or blogs. The planning tools mentioned in Figure 3 include, for example, Google Calendar or Outlook Calendar. Examples of documents on the network in Figure 4 are Google Drive and SkyDrive. The mind maps in Figure 5 are created using tools like Cmaptool, Mindomo, Text2mindmap, Bubbl. The presentation tools in Figure 6 include Prezi, SlideShare, Scribd, and Canvas, among others. The podcasting and videocasts mentioned in Figure 7 can be created using tools like Flicks, Odeo, and YouTube. Finally, for sharing information via QR codes, various free tools like qrcode-generator are available.

4. Discussion

The analysis of the results obtained in this study on the relationship between the development of digital skills and students’ collaboration attitudes in educational environments provides a deeper understanding of how these two variables are interconnected and their implications for teaching and learning. It underscores the importance of digital skills in current education, aligning with other studies indicating that, as technology becomes increasingly integral in everyday life and the workplace [37,38], it is essential for students to develop strong digital skills. It emphasizes the consideration that digital skills not only encompass the technical ability to use digital tools but also the skills to communicate, collaborate, and problem-solve in digital environments [39].

Regarding hypothesis 1, the interplay between digital skills and collaboration in educational settings presents a multifaceted picture. On one hand, this study shows that a weak correlation is observed between the development of digital skills and virtual collaboration with professors (Figure 1). On the other hand, the scientific literature shows that collaboration is positively linked to the development of digital skills, as [23] points out, and as [25] suggests: the level of digital skills has a marked impact on students’ attitudes towards collaborative online learning. The weak correlation found in this study can be attributed to factors beyond digital competence, such as the structure of online courses, the quality of virtual interactions, and professors’ enthusiasm for fostering collaboration.

Additionally, the correlation becomes null when considering peer collaboration or in-person interactions with professors (Figure 1). This indicates that digital skills might not be pivotal in determining students’ willingness to collaborate with their peers. Instead, elements like group dynamics, personal interaction, and the nature of assigned tasks seem to hold greater significance in this context, as highlighted in studies by [40,41,42].

Research indicates that disparities in technological access can significantly impact the correlation between digital skills and virtual collaboration [43,44]. The digital divide, particularly in terms of income-related access to computers, can further exacerbate these disparities [43]. This is particularly problematic for digitally excluded youths, who face challenges in developing digital skills due to poor access to technology and limited support networks [44]. To address these disparities, it is crucial to provide students with opportunities to develop virtual collaboration skills, particularly in the context of a virtual work environment [45].

When examining the individual correlations between the 24 specific digital skills (Hypothesis 2) and collaboration, it is highlighted that some skills are more related to collaboration than others, but the differences are not significant. Those closely related skills become key areas of focus in teaching and curriculum development. Skills such as time planning, working with documents online, organizing and synthesizing information through concept maps, creating interactive online presentations, using podcasting and videocasting, and disseminating information through QR codes show the highest correlations with collaboration [46,47]. For instance, the ability to participate appropriately in forums, use time planning tools, and work with online documents positively correlates with collaboration. This suggests that students skilled in time management and digital content creation are more likely to actively collaborate in educational environments. A notable observation pertains to competencies A1, A2, A3, and A4, which are directly linked to the practice of communication (Table 8). Contrary to expectations, these competencies do not exhibit a stronger correlation with collaboration. The outcomes of this research present a divergence from the conclusions drawn in previous studies: [48,49] both highlight the potential of digital tools in enhancing collaborative creative work, with the latter also noting the need for new competencies to effectively utilize these tools. The authors of [50], contributing their perspective, discuss the use of eScience tools, including XML data representations and Web 2.0 social networking tools, to support collaboration and virtual organizations. This suggests that the interplay between communication-related skills and collaboration might be more complex than initially anticipated (Table 8).

However, the null correlation between the remaining specific digital skills and collaboration may be related to the design of educational environments and how collaboration is encouraged. In some cases, courses may not be fully leveraging the potential of digital tools to promote collaboration. Improving course design and effectively integrating digital tools could positively influence collaboration [51,52]. It is important to note that this null correlation does not necessarily imply that these digital skills are not valuable or relevant in the educational context, but refers to the fact that in-person collaboration with professors may depend on other factors, such as classroom dynamics, the professor’s willingness to encourage in-person collaboration, activity design, and other elements that go beyond students’ digital skills [53].

It is essential to recognize that the value of digital skills in the educational sphere extends beyond their direct correlation with collaborative outcomes. The absence of a strong link between specific digital skills and collaboration could stem from underutilized pedagogical strategies rather than the irrelevance of these skills.

5. Conclusions

The growing integration of technology in education has turned digital skills into an essential aspect of learning and preparation for the workforce. The results of this study underscore the importance of students acquiring strong digital skills to thrive in an increasingly digitized educational and work environment.

This study found a weak correlation between the development of digital competencies in university students and their attitudes towards collaboration in academic scenarios. Hence, the alternative hypothesis is invalidated, while the null hypothesis is affirmed. The rejection of the second alternative hypothesis is warranted due to the absence of statistically significant differences observed in the correlations between the collaboration and the digital competencies under investigation.

The complex relationship between digital skills and various forms of collaboration in educational environments necessitates a nuanced understanding of the multiple factors that influence these dynamics.

However, it is important to note that this study is based on data collected from a specific sample of university students in the field of Social Sciences. Therefore, there is potential for further research to explore these relationships in different educational contexts and student populations to gain a more comprehensive understanding of this evolving topic in contemporary education.

The results of this study should be interpreted taking into account several limitations, such as the fact that the level of digital competence was measured with a single instrument that could have been complemented by other instruments, such as interviews and focus groups, to enrich the results. The specific sample corresponds to students in the field of Social Sciences and only to Spanish universities. Future studies should include larger samples of university students from other disciplines and countries to draw more generalizable conclusions. Moreover, correlation does not imply causation, so it cannot be affirmed that the development of digital skills leads to an increase in collaboration. From a prospective perspective, it could be examined how course design and specific pedagogical strategies influence the relationship between digital skills and collaboration.

The relationship between digital skills and collaboration is complex and requires additional studies that include more diversified samples and complementary methodological approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.M.-G. and J.A.M.-M.; methodology, A.F.M.-G.; software, A.F.M.-G.; validation, A.F.M.-G., J.A.M.-M., E.F. and E.L.-M.; formal analysis, A.F.M.-G. and J.A.M.-M.; investigation, A.F.M.-G., J.A.M.-M., E.F. and E.L.-M.; data curation, A.F.M.-G. and J.A.M.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.M.-G.; writing—review and editing, A.F.M.-G. and E.F.; visualization, A.F.M.-G.; supervision, E.L.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in our research has been previously anonymized, and there is no possibility of identifying individuals within the data sets used. These data were obtained from public sources or databases that guarantee the confidentiality and privacy of the information of the original participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Potyrała, K. iEducation. Synergy of New Media and Didactics. Evolution—Antinomies—Contexts; Pedagogical University: Krakow, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Tondeur, J. The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Meneses, E. Information and Communication Technologies in University Praxis; Octaedro: Catalonia, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Gómez-García, M.; Ruiz-Palmero, J. Digital competence in research work: Predictors that have an impact on it according to the type of university and gender of the Higher Education teacher. Pixel-Bit. J. Media Educ. 2024, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Barahona, A.S.; Marqués-Molías, L.; Samaniego-Erazo, N.; Mejía-Granizo, C.M. Teacher Digital Competence. Design and validation of a training proposal. Pixel-Bit. J. Media Educ. 2023, 68, 7–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert-Cervera, M.; Esteve-Mon, F. Digital Learners: The digital competence of university students. Cuestión Univ. 2011, 7, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhaoa, Y.; Llorenteb, A.; Sánchez, M. Digital competence in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. 2021, 168, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero, S.; Vuorikari, R.; Punie, Y. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with Eight Proficiency Levels and Examples of Use, Luxembourg, Office of the European Union. 2017. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC106281/web-digcomp2.1pdf_(online).pdf (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Vuorikari, R.; Kluzer, S.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens—With New Examples of Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes, EUR 31006 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; ISBN 978-92-76-48883-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncuoglu, D. Analysis of digital and technological competencies of university students. Int. J. Educ. Math. Sci. Technol. (IJEMST) 2022, 10, 971–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Navío, E.; Ocaña-Moral, M.; Martínez-Serrano, M. University Graduate Students and Digital Competence: Are Future Secondary School Teachers Digitally Competent? Sustainability 2021, 13, 8519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sánchez Gómez, M.C.; Pinto Llorente, A.M.; Zhao, L. Digital Competence in Higher Education: Students’ Perception and Personal Factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganac, D.; Jović, D.; Novak, A. Digital Competencies in Selected European Countries among University and High-School Students: Programming is lagging behind. Bus. Syst. Res. J. 2022, 13, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martzoukou, K.; Kostagiolas, P.; Lavranos, C.; Lauterbach, T.; Fulton, C. A study of university law students’ self-perceived digital competences. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2022, 54, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koneva, D.A.; Lysenko, E.V.; Hoholeva, E.A. Assessment of Digital Competencies University Students: Case of the Ural Federal University Named after the First President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin. Manag. Pers. Intellect. Resour. Russ. 2022, 11, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Trail, T.; Lewis, D.Y.; Lopez, S. Examining the relationship among student perception of support, course satisfaction, and learning outcomes in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 2011, 14, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Liu, Y.; Johnson, L. Group regulation and socialemotional interactions observed in computer supported collaborative Learning: Comparison between good vs. poor collaborators. Comput. Educ. 2014, 78, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sellés, N. Tools that facilitate collaborative learning in virtual environments: New opportunities for the development of digital learning ecologies. Educ. Siglo XXI 2021, 39, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Zhang, M.Y.; Qi, D. Effects of different interactions on students’ sense of community in e-learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2017, 115, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sellés, N.; Muñoz-Carril, P.Y.; González-Sanmamed, M. Computer-supported collaborative learning: An analysis of the relationship between interaction, emotional support and online collaborative tools. Comput. Educ. 2019, 138, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, U.Y.; Usluel, Y. Knowledge building and the quantity, content and quality of the interaction and participation of students in an online collaborative learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2016, 97, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, M.; Bernal, C. The profile of teachers in the Network Society: Reflections on the digital competence of students in Education at the University of Cádiz. Int. J. Educ. Res. Innovat. 2019, 11, 83–100. Available online: https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/IJERI/article/view/3265 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Saputra, N.; Nugroho, R.; Aisyah, H.; Karneli, O. Digital skill during COVID-19: Effects of digital leadership and digital collaboration. J. Apl. Manaj. 2021, 19, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, J.; Vuorikari, R.; Costa, P.; Hippe, R.; Kampylis, P. Teacher collaboration and students’ digital competence—Evidence from the SELFIE tool. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 46, 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, W.; Wiśniewska-Nogaj, L. Digital Skills and Online Collaborative Learning: The Study Report. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2022, 20, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yooyativong, T. Developing Teacher’s Digital Skills Based on Collaborative Approach in Using Appropriate Digital Tools to Enhance Teaching Activities; 2018 Global Wireless Summit (GWS): Chiang Rai, Thailand, 2018; pp. 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.; Schumacher, S. Educational Research: A Conceptual Introduction; Pearson-Addison Wesley: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Concepción, J.; López-Meneses, E.; Vásquez-Cano, E.; Crespo-Ramos, S. Implication of previous training and personal and academic habits of use of the Internet in the development of different blocks of basic digital 2.0 competencies in university students. Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. (IJERI) 2022, 18, 18–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, E.; Trujillo, J.; Castaño, H. Descifrando el currículum a través de las TIC: Una visión interactiva sobre las competencias digitales de los estudiantes de Ciencias del Deporte y de la Actividad Física. Rev. Humanidades 2017, 31, 195–214. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6004965 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Veytia, M.G. Competencias básicas digitales en estudiantes de posgrado. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. Super. 2013, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Borges, C.A.; Rodríguez Zidán, C.E.; Zorrilla Salgador, J.P. Integration of mobile devices in initial training and educational practices of Uruguayan teaching students. Lat. Am. J. Comp. Educ. 2018, 9, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Scordino, R.; Geurtz, R.; Navarrete, C.; Ko, Y.; Lim, M. A Look at Research on Mobile Learning in K–12 Education from 2007 to the Present. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2014, 46, 325–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Cano, E.; Sevillano-García, M.L.; Fombona-Cadavieco, J. Analysis of the educational and social use of digital devices in the pan-Hispanic university context. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 34, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Major, L.; Hassler, B.; Hennessy, S. Tablets in schools: Impact, affordances and recommendations. In Handbook for Digital Learning in K-12 Schools; Marcus-Quinn, A., Hourigan, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 115–128. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Fernández, Z.; Neri, C. University students, ICT, and learning. Res. Yearb. 2013, 20, 153–158. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Association for Media Research. Internet Users Survey. Infographic, Summary 21: October to December 2018. 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/2TPXtN3 (accessed on 16 November 2023).[Green Version]

- Fernández, F.; Fernández, M. Teachers of Generation Z and their digital skills. Comunicar 2016, 24, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J. Computational Thinking, Computational Literacy, or Digital Competence? New challenges in education. Educ. Contemp. Cult. 2019, 16, 43–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Garcés, J.; Garcés-Fuenmayor, J. Teacher Digital Skills and the Challenge of Virtual Education Derived from COVID-19. Educ. Humanismo 2020, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, P.; O’Donnell-Allen, C. Reading as Mediated and Mediating Action: Composing Meaning for Literature through Multimedia Interpretive Texts. Read. Res. Q. 1998, 33, 198–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladevéze, L.; Canal, M.; Núñez, J. Regulatory affectivity as the foundation of domestic authority in the digital society. Lat. Am. J. Soc. Commun. 2017, 72, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez Larghi, S. Building student digital skills around the Connect Equality Program. Sci. Teach. Technol. 2020, 60, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, M.; Wade, B. The Digital Divide and First-Year Students. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynon, R.; Geniets, A. The digital skills paradox: How do digitally excluded youth develop skills to use the internet? Learn. Media Technol. 2016, 41, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.K.; Meglich, P.A. Preparing students to collaborate in the virtual work world. High. Educ. Ski. Work-Based Learn. 2013, 3, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Gómez, M.; Guzmán Acuña, J.; González, V.M. Learning through Search: From Information to Knowledge; University of Guadalajara: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, F. Teaching Strategies: Research on Didactics in Educational Institutions in the City of Pasto. 2010. Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Colombia/fce-unisalle/20170117011106/Estrategias.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Dalsgaard, P.; Remy, C.; Frich, J.; MacDonald, L.; Mose, M. Digital tools in collaborative creative work. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (NordiCHI ’18), Oslo, Norway, 29 September–3 October 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavendiek, A.; Inkermann, D.; Vietor, T. Supporting Collaborative Design by Digital Tools—Potentials and Challenges. 2016. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Supporting-collaborative-design-by-digital-tools-%E2%80%93-Bavendiek-Inkermann/446e7a856e6c65bdf4ff4ef53a09eadf3838dc07 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Frame, I.; Austen, K.F.; Calleja, M.; Dove, M.T.; White, T.O.H.; Wilson, D.J. New tools to support collaboration and virtual organizations. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2009, 367, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Sagasta, A. Communication and collaboration skills in teacher education. Rev. Mediterránea Comun. 2017, 8, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes Adalid, G.M. Education for Digital Literacy in the Elderly: A Solution for access and Effective Use of Technology in the Workplace; University of Malaga: Málaga, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa-Rave, N.; Marín, A.G.; Arango-Vásquez, S.I. Collaborative teaching and learning scenarios mediated by technology to promote communicative interactions in higher education. RIED. Ibero-Am. J. Distance Educ. 2023, 26, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).