Developing Micro-Teaching with a Focus on Core Practices: The Use of Approximations of Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Practice-Based Teacher Preparation

2.2. Micro-Teaching

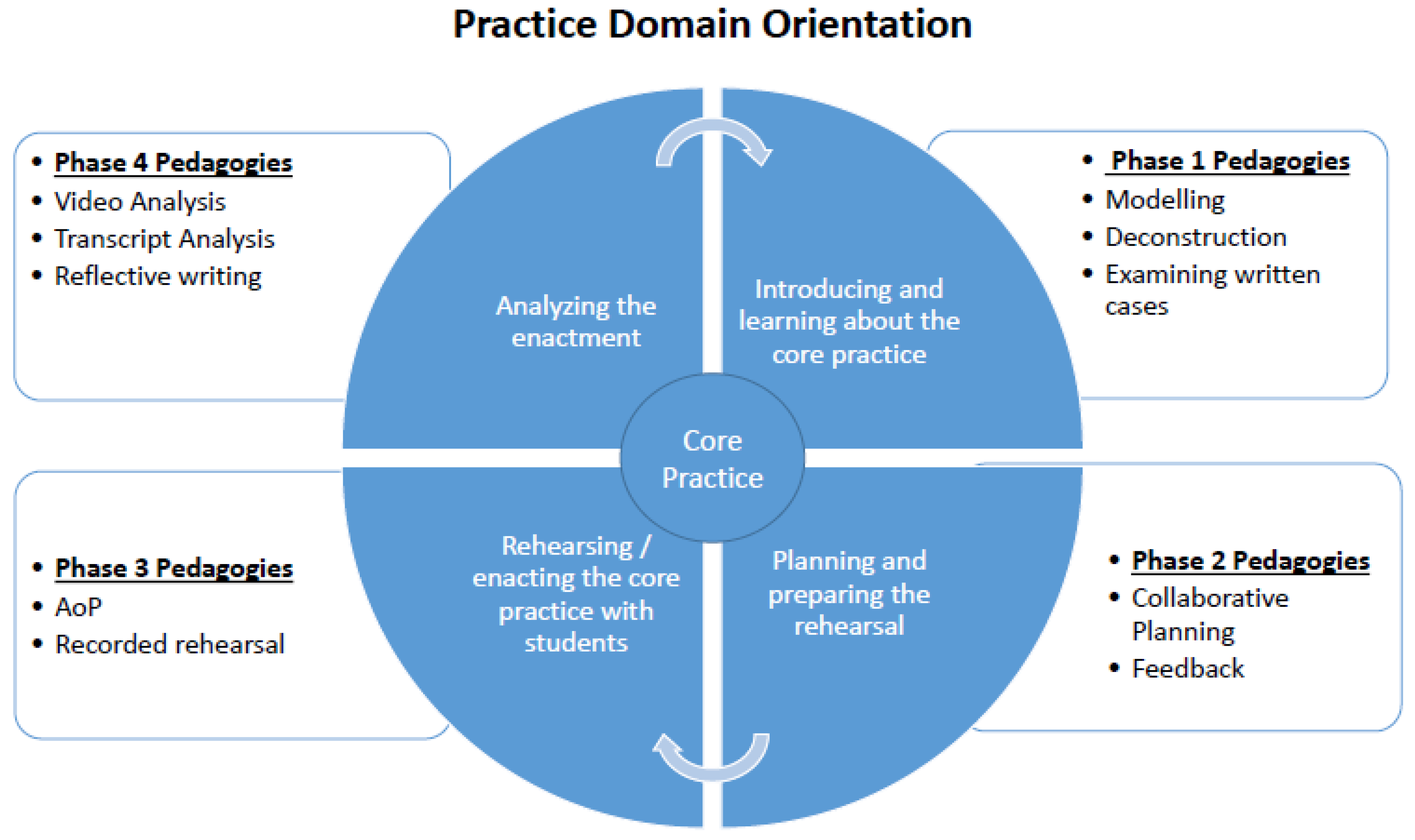

3. Description of the Micro-Teaching Model

Process

- Class routines/practices;

- Pupils’ prior knowledge/motivation with regards to the focus of the lesson (for example, Global Citizenship Education);

- Student engagement;

- Knowledge of the subject area: key themes/concepts;

- Selection of learning goals (including learning outcomes, learning intentions, and success criteria);

- Considerations for representation and expression and the resources required to facilitate the rehearsal.

4. Discussion and Implications for Practice

4.1. Selecting, Implementing and Evaluating Core Practices

4.2. Scaffolding Engagement with Investigation of Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Stringer Keefe, E.; Cummings Carney, M.; Sánchez, J.G.; Olivo, M.; Jewett Smith, R. Teacher Preparation at New Graduate Schools of Education. Teach. Educ. Q. 2020, 47, 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Accountability in Teacher Education. Action Teach. Educ. 2020, 42, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollins, E.R. Teacher Preparation For Quality Teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 62, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.M. Valuing practice over theory: How beginning teachers re-orient their practice in the transition from the university to the workplace. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2009, 25, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, R. The School–University Nexus and Degrees of Partnership in Initial Teacher Education. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2023, 42, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, K.; Schrittesser, I.; Knapp, M. Overcoming the theory-practice divide in teacher education with the ‘Partner School Programme’. A conceptual mapping. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.L.; Forzani, F.M. The Work of Teaching and the Challenge for Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 60, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Hammerness, K.; McDonald, M. Redefining Teaching, Re-Imagining Teacher Education. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2009, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, M.R.; Bemiss, E.M.; Shimek, C.; Van Wig, A.; Hopkins, L.J.; Davis, S.G.; Scales, R.Q.; Scales, D.W. Examining learning experiences designed to help teacher candidates bridge coursework and fieldwork. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 107, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.; Kazemi, E.; Kavanagh, S. Core Practices of Teacher Education: A Call for a Common Language and Collective Activity. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Compton, C.; Igra, D.; Ronfeldt, M.; Shahan, E.; Williamson, P. Teaching practice: A cross-professional perspective. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2009, 111, 2055–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S.; Conrad, J.; Dagogo-Jack, S. From rote to reasoned: Examining the role of pedagogical reasoning in practice-based teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 89, 102991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brataas, G.; Staal Jenset, I. From coursework to fieldwork: How do teacher candidates enact and adapt core practices for instructional scaffolding? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132, 104206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forzani, F.M. Understanding ‘Core Practices’ and ‘Practice-Based’ Teacher Education: Learning from the past. J. Teach. Educ. 2014, 65, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, J.; Beal, E.M. Core Competencies and High Leverage Practices of the Beginning Teacher: A Synthesis of the Literature. J. Educ. Teach. 2018, 44, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P. (Ed.) Teaching Core Practices in Teacher Education; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jenset, I.S. The enactment approach to practice-based teacher education coursework: Expanding the geographic scope to Norway and Finland. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, M. Learning teaching in, from, and of practice: What do we mean? J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleep, L. Teaching to the Mathematical Point: Knowing and using Mathematics in Teaching. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Education) at the University of Michigan. 2009. Available online: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/64676/sleepl_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Cuenca, A. Proposing Core Practices for Social Studies Teacher Education: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Inquiry-Based Lessons. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 72, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkelman, T.; Cuenca, A. A Turn to Practice: Core Practices in Social Studies Teacher Education. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 2020, 48, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P. Teaching Core Practices in Teacher Education; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, S.; Metz, M.; Hauser, M.; Fogo, B.; Taylor, M.; Carlson, J. Practicing responsiveness: Using approximations of teaching to develop teachers’ responsiveness to students’ ideas. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 71, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S.; Rainey, E.C. Learning to support adolescent literacy: Teacher educator pedagogy and novice teacher take up in secondary English language arts teacher preparation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 54, 904–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.L. The Pedagogy of Video: Practices of Using Video Records as a Resource in Teacher Education. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 April–1 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hlas, A.C.; Hlas, C.S. A Review of High-Leverage Teaching Practices: Making Connections between Mathematics and Foreign Languages. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2012, 45, S76–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, C.L.; Danielson, K.A.; Dutro, E.; Cartun, A. Does a discussion by any other name sound the same? Teaching discussion in three ELA methods courses. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 69, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, P. Enacting high leverage practices in English methods: The case of discussion. Engl. Educ. 2013, 46, 34–67. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24570973 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Ball, D.L.; Forzani, F.M. Teaching Skillful Teaching. Educ. Leadersh. 2010, 68, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew, S.; Alston, C.L.; Fogo, B. Modeling as an example of representation. In Teaching Core Practices in Teacher Education; Grossman, P., Ed.; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Grosser-Clarkson, D.; Neel, M.A. Contrast, commonality, and a call for clarity: A review of the use of core practices in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 71, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldinger, E.E.; Munson, J. Developing adaptive expertise in the wake of rehearsals: An emergent model of the debrief discussions of non-rehearsing teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 95, 103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerness, K.M.; Darling-Hammond, L.; Bransford, J.; Berliner, D.; Cochran-Smith, M.; McDonald, M. How teachers learn and develop. In Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers Should Learn and Be Able to Do; Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 358–389. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M. The role of preservice teacher education. In Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Teaching and Policy; Darling-Hammond, L., Sykes, G., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 54–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, M.; Kavanagh, S.S. Practice-based teacher education. In Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, K.M.; Danielson, K.A.; Cohen, J. Approximations in English language arts: Scaffolding a shared teaching practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 81, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A. Attaining excellence through deliberate practice: Insights from the study of expert performance. In The Pursuit of Excellence in Education; Ferrari, M., Ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Meneses, A.; Nussbaum, M.; Veas, M.G.; Arriagada, S. Practice-based 21st century teacher education: Design principles for adaptive expertise. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 128, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesje, K.; Lejonberg, E. Tools for the school-based mentoring of preservice teachers: A scoping review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 111, 103609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. Parsing the Practice of Teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 67, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, T.M.; Souto-Manning, M.; Anderson, L.; Horn, I.; Carter Andrews, D.J.; Stillman, J.; Varghese, M. Making justice peripheral by constructing practice as “core:” How the increasing prominence of core practices challenges teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. The turn once again toward practice-based teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 63, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano Beltramo, J.; Stillman, J.; Struthers Ahmed, K. From Approximations of Practice to Transformative Possibilities: Using Theatre of the Oppressed as Rehearsals for Facilitating Critical Teacher Education. New Educ. 2020, 16, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, J.; Baldinger, E.E.; Larison, S. What if … ? Exploring thought experiments and non-rehearsing teachers’ development of adaptive expertise in rehearsal debriefs. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 97, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.W. A new design for teacher education: The teacher intern program at Stanford University. J. Teach. Educ. 1966, 17, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.A.A. Student Teachers’ Microteaching Experiences in a Preservice English Teacher Education Program. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2011, 2, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogeyik, M.C. Attitudes of the Student Teachers in English Language Teaching Programs towards Microteaching Technique. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2009, 2, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, A.; Nicholl, H. The experiences of lecturers and students in the use of microteaching as a teaching strategy. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2003, 3, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, E.G. The Effectiveness of Microteaching: Five Years’ Findings. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Educ. (IJHSSE) 2014, 1, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Remesh, A. Microteaching, an efficient technique for learning effective teaching. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen, D.W.; Clark, R.J. Microteaching: It’s Rationale. High Sch. J. 1967, 51, 75–79. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40366699 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Allen, D.W.; Ryan, K. Microteaching; Addison-Wesley: Massachusetts, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Limbacher, P.C. A Study of the Effects of Microteaching Experiences Upon the Classroom Behaviour of Social Studies Student Teachers; American Education Research Association: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, B.E. A Survey of Microteaching in NCATE-Accredited Secondary Education Programs. Research and Development Memorandum, Stanford Center for Research and Development in Teaching, Stanford University. 1970. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED046894 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Ferguson, S.; Sutphin, L. Analyzing the Impact on Teacher Preparedness as a Result of Using Mursion as a Risk-Free Microteaching Experience for Pre-Service Teachers. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2022, 50, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, N.B.; Kinay, I. An Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Opinions about Micro Teaching Course. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2021, 17, 226–240. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1318397.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.L. Investigating how and what prospective teachers learn through microteaching lesson study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, S.; Fischetti, J. Micro-teaching 2.0: Technology as the Classroom. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 36, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton-Kupper, J. The microteaching experience: Student perspectives. Education 2001, 121, 830–835. [Google Scholar]

- Burnaford, G.; Fischer, J.; Hobson, D. (Eds.) Teachers Doing Research; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoff, A.E. The teacher as researcher. In Reclaiming the Classroom: Teacher Research as an Agency for Change; Goswami, D., Stillman, P., Eds.; Boynton Cook: Upper Montclair, NJ, USA, 1987; pp. 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Lytle, S.L. (Eds.) Inside/Outside: Teacher Research and Knowledge; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, M.L.; Kazemi, E. Learning to teach mathematics: Focus on student thinking. Theory Into Pract. 2001, 40, 102–109. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1477271 (accessed on 13 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Goffree, F.; Oonk, W. Educating primary school mathematics teachers in the Netherlands: Back to the classroom. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 1999, 2, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, P.; Mousley, J. Learning about teaching: The potential of specific mathematics teaching examples presented on interactive media. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Valencia, Spain, 8–12 July 1996; Puig, L., Gutierrez, A., Eds.; International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education: Valencia, Spain, 1996; pp. 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Mergler, A.G.; Tangen, D. Using microteaching to enhance teacher efficacy in pre-service teachers. Teach. Educ. 2010, 21, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msimang Mothofela, R. The Impact of Micro Teaching Lessons on Teacher Professional Skills: Some Reflections from South African Student Teachers. Int. J. High. Educ. 2021, 10, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, D. Learning in Groups—A Handbook for Improving Group Work, 3rd ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Şen, A.I. A study on the Effectiveness of Peer Microteaching in a Teacher Education Program. Educ. Sci. 2009, 34, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Sevim, O.; Suroglu Sofu, M. The Effects of Extended Micro-Teaching Applications on Foreigners’ Views on Motivation, and Process of Learning Turkish. Int. J. High. Educ. 2021, 10, 135–150. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1310414.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Powerful Teacher Education: Lessons from Exemplary Programs; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Woolfolk Hoy, A.; Burke Spero, R. Changes in teacher efficacy during the early years of teaching: A comparison of four measures. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, D. Teaching Skills in Further and Adult Education; MacMillan Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cajkler, W.; Wood, P.; Norton, J.; Pedder, D. Lesson Study: Towards a collaborative approach to learning in Initial Teacher Education? Camb. J. Educ. 2013, 43, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.A. Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice, 2nd ed.; Adams, M., Bell, L.A., Grifn, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarr, O.; McCormack, O. Reflecting to Conform? Exploring Irish Student Teachers’ Discourses in Reflective Practice. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 107, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, M.; Franke, M.; Kazemi, E.; Ghousseini, H.; Turrou, A.; Beasley, H.; Crowe, K. Keeping it complex: Using rehearsals to support novice teacher learning of ambitious teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.L.; Valencia, S.W.; Evans, K.; Thompson, C.; Martin, S.; Place, N. Transitions into teaching: Learning to teach writing in teacher education and beyond. J. Lit. Res. 2000, 32, 631–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Kavanagh, S.S.; Dean, C.G.P. The turn towards practice in teacher education: An introduction to the work of the Core Practice Consortium. In Teaching Core Practices in Teacher Education; Grossman, P., Ed.; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kohen, Z.; Borko, H. Classroom discourse in mathematics lessons: The effect of a hybrid practice-based professional development program. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2019, 48, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloser, M.; Wilsey, M.; Madkins, T.C.; Windschitl, M. Connecting the dots: Secondary science teacher candidates’ uptake of the core practice of facilitating sense making discussions from teacher education experiences. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 80, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.; Grossman, P.; Westbroek, H. Facilitating decomposition and recomposition in practice-based teacher education: The power of modularity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Windschitl, M. How does practice-based teacher preparation influence novices’ first-year instruction? Teach. Coll. Rec. 2018, 120, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallchóir, C.Ó.; O’Flaherty, J.; Hinchion, C. My cooperating teacher and I: How pre-service teachers story mentorship during School Placement. J. Educ. Teach. 2019, 45, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. The role of mentor teacher-mediated experiences for preservice teachers. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 72, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. Competition, economic rationalization, increased surveillance, and attacks on diversity: Neo-liberalism and the transformation of teacher education in the U.S. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, I.S.; Campbell, S.S. Developing pedagogical judgment in novice teachers: Mediated field experience as a pedagogy for teacher education. Pedagog. Int. J. 2015, 10, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S.S.; Danielson, K.A.; Schiavone Gotwalt, E. Preparing in advance to respond in-the-moment: Investigating parallel changes in planning and enactment in teacher professional development. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 00224871221121767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotwalt, E.S. Putting the purpose in practice: Practice-based pedagogies for supporting teachers’ pedagogical reasoning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 122, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, R.; O’Flaherty, J. Factors that predict pre-service teachers’ teaching performance. J. Educ. Teach. 2018, 44, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrosky, M.M.; Mouzourou, C.; Danner, N.; Zaghlawan, H.Y. Improving teacher practices using microteaching: Planful video recording and constructive feedback. Young Except. Child. 2013, 16, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerness, K. Examining features of teacher education in Norway. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 57, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, H.; Jacobs, J.; Eiteljorg, E.; Pittman, M.E. Video as a tool for fostering productive discussions in mathematics professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; van Es, E.A. Articulating design principles for productive use of video in preservice education. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körkkö, M.; Morales Rios, S.; Kyrö-Ämmälä, O. Using a video app as a tool for reflective practice. Educ. Res. 2019, 61, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, T.; van Es, E.A. Studying teacher noticing: Examining the relationship among pre-service science teachers’ ability to attend, analyze and respond to student thinking. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 45, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cycle 1: Peer Teach (MT1) | Cycle 2: Micro-Teach 2 (MT2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lesson Focus | AoP: Introducing a new topic (GCE) | AoP: Facilitating a Group Discussion |

| Structure of Experience | Plan; Implement; Review; Evaluate | Plan; Implement; Review; Evaluate |

| Small groups (5/6 students) | Small groups (5/6 students) | |

| Lessons are recorded | Lessons are recorded | |

| Implementation setting | Peer Teach | Pupils aged 12–14 years |

| Reduced class size (6 students) | Reduced class size (6 students) | |

| Reduced Lesson length (8–10 min) | Reduced Lesson length (8–10 min) | |

| Review/Evaluation Structure | Participant Review Independent Review | Participant Review Independent Review Tutor Review |

| Forms of Feedback | Participant Feedback Use of recorded lesson Tutor Feedback | Pupil Feedback Feedback from peers Use of recorded lesson: Medals and Missions Tutor Feedback |

| Reflective Process | Individual Written Reflection | Individual Written Reflection |

| Outputs | Partial Lesson Plan Participant Feedback Report Apply to full draft of individual lesson plan | Partial Lesson Plan Peer Feedback Report Self-Assessment Apply to full draft of individual lesson plan |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Flaherty, J.; Lenihan, R.; Young, A.M.; McCormack, O. Developing Micro-Teaching with a Focus on Core Practices: The Use of Approximations of Practice. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010035

O’Flaherty J, Lenihan R, Young AM, McCormack O. Developing Micro-Teaching with a Focus on Core Practices: The Use of Approximations of Practice. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Flaherty, Joanne, Rachel Lenihan, Ann Marie Young, and Orla McCormack. 2024. "Developing Micro-Teaching with a Focus on Core Practices: The Use of Approximations of Practice" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010035

APA StyleO’Flaherty, J., Lenihan, R., Young, A. M., & McCormack, O. (2024). Developing Micro-Teaching with a Focus on Core Practices: The Use of Approximations of Practice. Education Sciences, 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010035