Abstract

Entrepreneurship education (EE) plays a crucial role in equipping individuals with the necessary competences to thrive in an increasingly dynamic and competitive world. By fostering entrepreneurial competencies, recognizing individual abilities, and promoting innovation and creativity, EE contributes to personal growth, employability, and economic development. This document presents an analysis conducted on the entrepreneurial competencies (EC) of students in San Quintin, Baja California, Mexico, who have participated in a practical EE program over the past 5 years. To conduct the analysis, a questionnaire was administered to both a control group and an experimental group, and the data were captured in the SPSS V23 software for interpretation. The results demonstrate a significant correlation between EE programs and EC developed by the students in the experimental group. Therefore, it is recommended to promote and sustain such initiatives, aiming for their long-term continuity, strengthening, and growth.

1. Introduction

Education is a continuous voyage that aims to nurture essential characteristics in individuals and empower them with fresh capabilities [1]; EE has gained significant attention in recent years as a vital component of educational systems worldwide [2] (p. 18), and has emerged as a critical field within the broader realm of education, driven by the recognition of its significance in preparing individuals for the challenges and opportunities of the modern world [3,4,5]. In a time characterized by notable economic, social, and environmental obstacles, entrepreneurship has emerged as a powerful driver of economic advancement. Consequently, nations across the globe have been actively devising diverse strategies to promote entrepreneurship on a global level [6]. The development of entrepreneurial competences is increasingly recognized as crucial for individuals to navigate the challenges of the modern economy and contribute to social and economic growth [7] (p. 687).

Although genetics may have some influence, it is crucial to recognize that becoming an entrepreneur is shaped by multiple factors beyond genetics alone. According to Zunino, genetic factors may be further influenced by favorable institutional environments. This implies that while certain genetic predispositions may exist, the surrounding institutional context can either amplify or impede entrepreneurial inclinations [8]. Kuechle reinforces the idea that the entrepreneurship phenotype is heavily impacted by the environment. This indicates that environmental elements, including resource availability, support networks, and cultural perspectives on entrepreneurship, play a significant role in shaping an individual’s propensity for entrepreneurial pursuits [9].

In Mexico, as in many countries, microenterprises constitute the vast majority of the business landscape, comprising 94.9% of the total number of establishments [10]. Microenterprises face challenges due to limited education on navigating market demands and managing resources for their ventures. The National Survey on Productivity and Competitiveness of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (ENAPROCE) found that, since 2015, 98 out of every 100 businesses in manufacturing, trade, and services are microenterprises, employing over 75% of the workforce [11]. A significant percentage of entrepreneurs lack university degrees, as elementary-level EE programs are absent, preventing them from acquiring fundamental competencies needed for business comprehension and management. This stands in contrast to Mexico’s average of 9.1 years of schooling for individuals aged 15 and older [11].

This study was conducted in the region of San Quintin, situated in Baja California, Mexico. This rural and agricultural area holds immense potential for enhancing the quality of life. The entrepreneurial ecosystem in this region faces several challenges, a scenario that resonates across various parts of the country and globally. This context was selected as the research testing ground due to its relevance in reflecting similar situations worldwide.

While entrepreneurial culture hinges on external factors like training and financing [12], it is also tied to personal aspects, such as fostering creativity in educational settings, potentially beginning at the primary level [13]. Such environments can initiate and nourish EC through EE programs, aiding students in becoming more effective microentrepreneurs [14].

Due to the paramount importance of the subject, this study delves into the repercussions of early-stage EE initiatives among San Quintin’s young learners. This investigation holds the potential to offer a blueprint for analogous settings, shedding light on the enhancements in the entrepreneurial competences of children engaged in practical programs. Practical EE programs offer avenues to initiate EE without extensive curriculum modifications, recognizing the constraints in many regions. These practical entrepreneurial experiences can be delivered as extracurricular activities, external initiatives, or national programs [15]. For countries unable to revise their educational curriculum, these practical entrepreneurship programs offer a promising starting point [16].

Currently, micro, small, and medium enterprises, often managed by individuals lacking both the theoretical and practical tools for business creation, are reinforced by the educational level of microentrepreneurs and the competencies they develop through self-learning [17]. However, it is crucial to consolidate entrepreneurship through education [18], as while humans are born with entrepreneurial traits, formal education provides the means to actualize potentially successful ideas and enhance entrepreneurial competencies [19].

Although there are diverse interpretations and no defined consensus on the concept of competence [20], we will be referring to the following definitions. The amalgamation of knowledge, professional skills, and expertise that are adeptly mastered and applied within specific contexts [21]. In accordance with Brophy and Kiely [22] and Rankin [23], competencies encompass knowledge, values, skills, behaviors, and attitudes requisite for the successful execution of specific tasks, ranging from surgical procedures to the installation of household wiring.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

Although there is no universally accepted definition of EE [18], the European Commission [24] outlines two approaches to its concept development and application: one focusing solely on teaching entrepreneurial activities and enterprise creation, while the second emphasizes EE as a key competence for comprehensive preparation. According to the European Union’s (EU) Thematic Working Group on EE, the latter approach envisions EE as fostering the skills and mindsets needed to translate creative ideas into entrepreneurial actions. It is a pivotal competence for all students, contributing to personal development, active citizenship, social inclusion, and employability. Furthermore, its relevance spans lifelong learning, all knowledge disciplines, and education formats, supporting entrepreneurial spirit or behaviors, whether commercial or not [15].

If entrepreneurs contribute to economic growth, then instilling an education promoting an entrepreneurial attitude is significant [25]. However, fostering entrepreneurship competence [26] through compulsory schooling is not solely economic [27]. It is rooted in the belief that enhancing entrepreneurship capacity pedagogically grounds personal autonomy in the social context [28]. While EE can cultivate attitudes like self-confidence, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and the need for achievement [29], Freire [30] argues that having talent and even entrepreneurial traits is insufficient without developing them into competencies through training and technical learning. Noworatzky [31] states that entrepreneurship can be learned, and entrepreneurial intent can be stimulated. However, incorporating mechanisms into educational systems for integrating innovation and entrepreneurship, throughout all levels, remains a significant challenge [32].

The British Household Survey suggests a higher likelihood of students starting their own businesses after being exposed to entrepreneurial initiatives, facilitated by friends, family, and crucially, education [33]. EE at the primary level imparts early knowledge of business matters, facilitating engagement with the entrepreneurial world, and helping children understand entrepreneurs’ roles in the community [18].

EE has been recognized as a means to foster various competencies and attributes, including creativity, opportunity recognition, risk-taking propensity, and the ability to innovate [2,4,5,34]. It equips individuals with the necessary competences to identify opportunities, take calculated risks, and transform ideas into tangible outcomes. Moreover, EE promotes self-confidence, resilience, adaptability, and critical thinking, essential attributes in an ever-evolving global landscape [35]. By nurturing these competences, EE contributes to personal development, employability, and economic growth [7]. By equipping individuals with the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes, EE empowers them to identify and pursue opportunities, solve problems, and contribute to economic growth and job creation [3,5].

1.2. Experiences of Entrepreneurship Education

One hypothesis currently being explored is the relationship between EE and the recognition of individual abilities; Pinho et al., conducted a qualitative study on the UKIDS project, which focused on elementary school children in six countries [36]. The findings suggested that entrepreneurship education positively impacted the recognition of individual abilities, such as creativity, self-confidence, persuasive skills, and the development of social competencies. This hypothesis aligns with the idea that entrepreneurship education provides a platform for students to explore and harness their unique talents [2].

In contrast, there are debates surrounding the most effective pedagogical approaches in entrepreneurship education. Likar et al., proposed a model in Slovenia that included innovation and creativity clubs, elective subjects, and training for teachers and school administrators [37]. This approach aimed to address the demand for implementing innovative techniques in education, while considering the current context. However, some scholars argue for a more integrated approach, embedding entrepreneurship education across various disciplines and subjects [38]. This controversy highlights the need for further research to determine the optimal strategies for delivering EE.

The current landscape of EE is characterized by diverse approaches, ranging from formal programs integrated into educational institutions to informal initiatives and experiential learning opportunities [37,39]. However, there are still controversies and divergent perspectives within the field, such as EE programs’ appropriate timing and duration [37,40]. These debates contribute to ongoing discussions and shape the direction of EE research and practice. Regardless, during the early 2000s, the OECD advised its member nations to integrate entrepreneurship-focused subjects into their educational frameworks across all levels. In the case of Mexico, though, these subjects were initially incorporated solely in high schools and universities that provided technological and economic-administrative programs [6]. The inclusion of entrepreneurship education at the elementary level plays a pivotal role in fostering the growth of critical thinking and problem-solving abilities among students [41].

In Mexico, Bernal, Sevilla, and Ramírez conducted a pilot test of the “My First Business: Entrepreneurship through Play” program, which involved creating mini companies with guidance from university advisors. The study highlighted the positive impact of the program on the children’s abilities to delegate, communicate, handle conflicts, and set goals. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education interventions at an early age [42].

The integration of EE into curricula has also received considerable attention. In Québec, Canada, Pepin investigated the process of learning to be enterprising through a school shop initiative. The study demonstrated that actively engaging students in the establishment of the school shop and involving them in problem-solving, critical reflection, and interdisciplinary learning promoted enterprising competences. This research emphasizes the significance of hands-on, experiential learning in EE [43].

Rastiti, Widjaja, and Handayati conducted a study on vocational high school students to explore the influence of EE, economic literacy, the family environment, and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions [44]. The findings indicated that these factors positively affected entrepreneurial intentions, with self-efficacy playing a mediating role. The study highlights the importance of educational institutions providing support systems to foster entrepreneurial attitudes and abilities, as well as the need for additional economic knowledge and motivation to enhance students’ self-efficacy. Overall, the research emphasizes the significance of these factors in promoting an entrepreneurial mindset among vocational high school students.

In their study, Aral and Kılıçoğlu focus on the importance of sustainable EE during the early childhood period. They emphasize that entrepreneurship and EE should be based on childhood experiences and start at an early age. By introducing sustainable EE to children, it is believed that future generations will develop a perception of sustainable entrepreneurship and be able to utilize existing resources effectively. The researchers conducted a thorough literature review and compiled relevant studies thematically to explore the topic of sustainable EE for early childhood. Their findings highlight the significance of integrating sustainable EE into the early childhood curriculum [45]. Heilbrunn’s study examining an experimental case of entrepreneurial experience in an Israeli elementary school underscores the importance of addressing multiple dimensions to facilitate cognitive transformation in students [46]. The study emphasizes the need to enhance attitudes, foster a preference for innovation, and cultivate proactive dispositions, particularly within the context of entrepreneurship. This analysis highlights the significance of implementing a holistic educational approach that encompasses cognitive development, attitudinal shifts, and the promotion of entrepreneurial mindsets.

In a study by Kolvereid and Isaksen, it was found that EE increases the likelihood of individuals starting their own businesses [47]. This highlights the practical value of such education in fostering entrepreneurial endeavors. The influence of EE on students’ perceptions was explored by Peterman and Kennedy, who found that it positively shapes students’ attitudes, beliefs, and intentions toward entrepreneurship [48]. This suggests that EE plays a crucial role in shaping individuals’ entrepreneurial mindset. The Entrepreneurship Education Project, introduced by Vanevenhoven and Liguori, demonstrated the positive impact of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial competences and behaviors [49].

Entrepreneurship education has the potential to foster student interest, joy, commitment, and creativity. By providing students with opportunities to explore their entrepreneurial potential, engage in hands-on activities, and develop real-world problem-solving competences, entrepreneurship education can ignite a passion for entrepreneurship and instill a sense of excitement and dedication. Moreover, the emphasis on creativity within entrepreneurship education encourages students to think outside the box, explore innovative solutions, and embrace their unique talents and ideas. Overall, entrepreneurship education serves as a catalyst for nurturing a positive and dynamic learning environment that cultivates the essential qualities needed for entrepreneurial success [50].

EE has evolved to develop an enterprising mindset and competences applicable to various organizations, fostering creativity, innovation, and adaptability for growth and societal progress [51]. This highlights the practical benefits of EE in developing entrepreneurial competencies. And the role of teachers in EE was emphasized by Ruskovaara and Pihkala, who highlighted the significance of teacher characteristics, teaching methods, and support systems in fostering entrepreneurial competencies among students [52].

2. Materials and Methods

San Quintín, with 87,616 inhabitants, experiences high migratory dynamics. Each year, numerous families from the southern parts of the country migrate to the region for agricultural work. Over half (52.1%) of the area’s population originates from other states, with at least 11,500 individuals speaking Spanish and indigenous languages [53]. Most who come to San Quintín find employment on agricultural ranches, engaging in activities like land preparation, planting, harvesting, or the packaging of fruits and vegetables. Some seek temporary housing, while many decide to settle in the region. Typically, these are humble individuals who perceive greater opportunities in San Quintín compared to their hometowns in southern Mexico. The living conditions have improved over the years, with instances of the children of farmworkers pursuing university degrees, an achievement not feasible in their native villages.

In Mexico, the Higher Education-Business Foundation (FESE) was established by the National Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions (ANUIES), the Employers’ Confederation of the Mexican Republic (COPARMEX), the Ministry of Public Education (SEP), and the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT). Its objective is to promote an entrepreneurial culture in the country through a practical EE program called “My First Company: Entrepreneurship through Play”. This program aims to develop entrepreneurial competences in 5th- and 6th-grade children. A part of the pilot test was conducted in Tijuana, Mexicali, and Ensenada; a total of 387 individuals participated, including children, teachers, school administrators, staff, and parents. After six months of work, 24 mini companies were created by the children and their university advisors. As a result of their involvement in the project, the children enhanced their abilities to delegate, communicate, listen, manage conflicts, and measure goals through effective communication [42].

Between 2012 and 2014, the Faculty of Engineering and Business in San Quintín (FINSQ) at the Autonomous University of Baja California (UABC) participated in the FESE’s My First Company project, with the support of scholarships for the young participants. Subsequently (2015–2019), using university resources, the program continued under the name “Cimarroncitos Emprendedores de San Quintín” (CESQ), providing training for academic faculty and university students to serve as business advisors for the primary school children and establish mini companies. The stages in the program are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Utilized variables and dimensions.

Between 2015 and 2019, approximately 55 university students served as advisors, and a total of 76 mini companies were created. From the entire group of participating children, 280 who remained in the San Quintín Valley were identified as the target population for the research. To ensure a representative probabilistic sample with a 95% confidence level, the questionnaire was administered to 165 children from the experimental group and 165 children from the control group. Before that, a pilot test was conducted with 53 children from elementary schools in San Quintín, who had similar ages and characteristics to the students expected to be included in the research. The purpose was to identify uncommon words in children’s language and improve the questionnaire’s questions for administration.

The children in the sample responded to a questionnaire comprising 39 questions: 9 related to general information and 30 designed to assess EC. The questionnaire was adapted from the instrument developed by the Assessment Tools and Indicators for Entrepreneurship Education (ASSTE) expert group. This instrument was originally designed to evaluate the level of EC in children participating in the Youth Start program. It is aligned with the entrepreneurship competencies indicated by the theory and presented in the previous section of this document; the operationalization can be observed in Table 2. The questionnaire was divided into two main variables, each encompassing three relevant dimensions for EC development. Indicators were formulated to measure these dimensions, forming the basis for the questions.

Table 2.

Operationalization of the dimensions on entrepreneurship education in elementary school children.

The questionnaire underwent a pilot test to prevent errors from confusing or ambiguous questions. For this purpose, fieldwork was conducted, seeking access to primary school children in the San Quintín region. Groups of children with similar ages and characteristics to the anticipated participants in the actual study were selected. The pilot test involved 53 children and revealed certain flaws in the questions, such as unfamiliar words in children’s language and a lack of clarity in some questions, among other details. These issues were addressed and improved prior to administering the questionnaire to the target sample. After, all the questionnaires were administered between September and October 2019. The collected data were processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23, and the results were analyzed through comparative analysis of means for independent samples, correlation analysis between variables, and regression analysis.

The analysis of the results on the CESQ program was conducted mostly through quantitative research, specifically a transactional study. The data were collected at a single point in time to examine the correlation between the implementation of the CESQ and the entrepreneurial competencies (EC) developed by the participating children. To determine whether the EC of these children differed from those who did not participate in the program, a group of children and young people of the same ages, living under similar conditions in the same area, and with generally the same characteristics as the experimental group, was selected as the control group.

3. Results

The analysis of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is utilized to assess the reliability of the measurement instrument, with the alpha value ranging from zero to one. As the value approaches one, the reliability level increases and, typically, a coefficient higher than 0.7 is sought [54]. In the current study, the obtained value is 0.888, as indicated in Table 3. This value was derived from 100% of the captured questionnaires.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

As mentioned, the research study involved a sample of 330 respondents, and the results are presented in Table 4. The participation of both genders is approximately equal, with a slightly higher percentage of boys than girls. In terms of age, 12 years old is the most predominant at 33.6%, followed by 14 years old at 20.3%, and 13 years old represented 16.7%. The lowest proportion of respondents is 0.6%, represented by 16-year-old teenagers. It is important to mention the results obtained regarding the parents’ place of origin, 37.7% of fathers come from southern states in Mexico, such as Oaxaca, Chiapas, Guerrero, and Veracruz, and 36.7% of mothers also come from the same places, which is the largest group. These parents saw the need to migrate to improve their income and quality of life. Regarding the state of Baja California, fathers are represented at 17.9%, while mothers are represented at 27.9%, indicating that mothers are mostly native to the state. This study focuses on San Quintín, Baja California, a rural area with a significant migrant population doing agricultural work [53]. It has a population of 117,568 [55], with 52.1% coming from other states and some speaking indigenous languages [53]. Education has improved the residents’ quality of life [56]. In the CE program, children from bilingual schools in San Quintín participate, including those from migrant families [55]. Indigenous languages are being lost, but bilingual schools promote their preservation. Many find work in agricultural ranches, and some families settle permanently in the region. Opportunities to progress in the north attract them more than in their hometowns [55]. Some have pursued higher education, which is a remarkable achievement [56].

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

The results on the most prominent occupations of the parents are represented as follows, in Table 5, 33.9% as day laborers, 3% as mechanics, 4.5% as masons, and 2.1% as teachers. Additionally, 25.2% of the respondents stated that they are unaware of their parents’ occupations. They mentioned that their parents are engaged in technical trades and basic commercial activities that do not require a professional degree. This reinforces the information presented about the regional context, as the majority of these children’s parents arrived in San Quintín in search of a better quality of life, many of them continue to work as day laborers on agricultural farms, while others have various occupations related to the field and the people who work in agriculture.

Table 5.

Occupations of the parents.

The responses from the participants regarding the presence of a business or entrepreneurial activity by someone close to them are presented in Table 6, the descriptive results indicate that 38.8% of them have relatives who have developed a business idea. On the other hand, 35% of the respondents do not have any family members who own a company. Additionally, neither the parents nor the mothers are entrepreneurs, indicating that the teenagers lack a supportive environment to develop or consider creating any entrepreneurial intentions. The British Household Survey refers to a higher likelihood of students starting their own businesses once they have been in contact with other entrepreneurial initiatives, either through their friends, family, or, most importantly, through education [33]. Some students, like those shown in Table 2 of our research, do not have contact with entrepreneurial individuals, which is why the European Commission report titled “A New Concept of Education: Investing in Skills for Better Socioeconomic Outcomes”, recommended that every young person should have a hands-on entrepreneurial experience before completing compulsory education. The report emphasizes the importance of investing in competences to achieve improved socioeconomic outcomes [27].

Table 6.

Someone close to you has a business.

Similarly, Table 7 shows the responses to the question on whether they have supported the tasks of a family business, 67.6% indicate no, while 32.4% indicate yes. This aligns with the previous question, as most teenagers do not have parents that are entrepreneurial figures in their lives. Oe and Tanaka made a study to examine the effectiveness of scaffolding materials in entrepreneurship education, using the social learning theory framework. The results show that the conventional business analysis model taught in lectures overlooks non-economic factors and real-life situations, emphasizing the importance of considering the sociocultural context. The scaffolding materials helped learners understand the conceptual model in a practical context, stimulated class discussions, and deepened comprehension. Additionally, the materials encouraged reflection and storytelling, enhancing self-awareness and learning outcomes. The study highlights the value of social learning theory in designing effective learning support measures for entrepreneurship education [57].

Table 7.

Have you supported or do you support tasks in a family business?

In a study conducted in Aguascalientes, Mexico, the entrepreneurial spirit of students was examined. The focus of the study was to compare students who had self-employed parents with those whose parents were not self-employed. Seven dimensions of entrepreneurial spirit were analyzed, including self-confidence, innovative behavior, achievement motivation, emotional self-efficacy, leadership, proactivity, and tolerance for uncertainty. The findings revealed significant differences in all dimensions, favoring the children of self-employed mothers. Additionally, the children of self-employed fathers showed advantages in the dimensions of self-confidence and innovative behavior. The results highlight the significant impact of strengthening maternal entrepreneurial activity on the development of entrepreneurial spirit in their children [58].

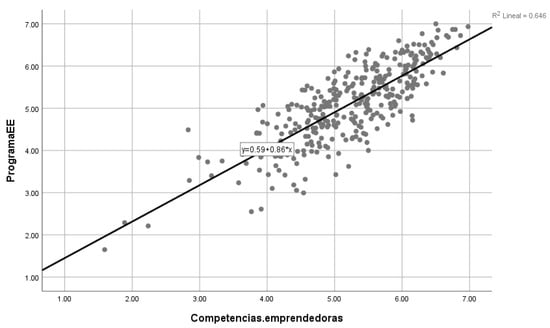

Table 8 and Figure 1 demonstrate a positive correlation between the two variables, indicating that an increase in practical programs for students (independent variable) leads to a corresponding improvement in their entrepreneurial competences (dependent variable). This finding confirms that while there are areas for improvement in the development of such programs, their implementation is positively impacting the lives of the participating children.

Table 8.

Pearson correlation.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot. Vertical: EE programs; horizontal: entrepreneurship competences. Source: Self-generated from the SPSS database.

Table 9 presents the standardized beta coefficient, which helps quantify the contribution of each independent dimension to the dependent variable. The dimension that contributes the most is knowledge of social entrepreneurship with 36%, followed by entrepreneurial knowledge at 34.4%, and, lastly, the teaching–learning process contributes 28.4%. The observed significance value is less than 0.05 for all three dimensions, indicating that the data is statistically significant. In line with this, the Youth Start program report showed a greater positive influence on students who had prior experiences with social entrepreneurship education, reinforcing our findings regarding social entrepreneurship as the most influential dimension in developing entrepreneurial competences [59]. However, the other dimensions used in this study are also relevant and should be further strengthened. One area of opportunity for the CE program is the implementation of modules dedicated to personal finance or economic reasoning, as the current material provides very little or no emphasis on these aspects. There are programs implemented in other countries, such as the “Me and Economics” program or the entrepreneurship educational program JA-YE, where children can benefit from this valuable tool that provides the foundation for acquiring and understanding economic concepts in the future [60].

Table 9.

Regression analysis.

Table 10 contains the ANOVA variance statistic that measures the critical level of significance. If it is less than or equal to 0.05, it determines whether the hypothesis of variances is met or not, indicating whether significant differences exist between the groups. In the conducted study, it is shown that entrepreneurial mindset and business competences significantly influence, while the relationship between entrepreneurship and the labor market is not significant. Hence, entrepreneurship is not considered a competitive strategy regarding the labor market demand, and there is no association between job opportunities and entrepreneurial actions. Our study shows that implementing a practical EE program significantly improved participants’ entrepreneurial mindset, including their thinking, self-assessment, attitudes, and skills. Similar positive effects were found in previous research, indicating that entrepreneurship education enhances creativity, self-confidence, persuasive skills, and social competencies [36,37]. Different approaches, from formal programs to experiential learning opportunities, foster innovation, and economic understanding [37,39,60]. The program also benefited children by enhancing their delegation, communication, conflict management, and goal-setting abilities [18]. Other studies emphasize the importance of educational support systems and additional economic knowledge to promote an entrepreneurial mindset among vocational high school students [20]. Finally, early integration of sustainable entrepreneurship education, starting from childhood experiences, is deemed significant [43,45].

Table 10.

ANOVA variance.

It is evident that actions need to be taken to help young people connect their passions with entrepreneurship. However, it should be noted that the children who participated in this activity were very young and may not have a clear vision of their future aspirations. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize the integration of entrepreneurship and work-related competences in schools to cultivate professionals who can make positive changes in their environment through their chosen careers.

4. Conclusions

The present discussion provides valuable insights into the significance of EE programs in fostering an entrepreneurial mindset and developing EC among young learners. Our San Quintín study demonstrated that the practical implementation of an EE program led to substantial improvements in participants’ entrepreneurial thinking, self-assessment, attitudes toward entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial skills. These findings support the effectiveness of such programs in facilitating the holistic development of entrepreneurial abilities among children.

Furthermore, the inclusion of innovation and creativity clubs, elective subjects, and teacher and administrator training, as proposed by Likar et al., proved to be successful in promoting innovation and creativity among students [37]. Moreover, the incorporation of formal programs in educational institutions, as highlighted by Damian and Cobos, and Denegri and Sepulveda, along with informal initiatives and experiential learning opportunities, has shown positive outcomes in terms of fostering innovation, creativity, and economic understanding [39,60]. These findings emphasize the importance of diverse approaches to entrepreneurship education, catering to the unique needs and contexts of learners. Entrepreneurial endeavors go beyond mere economic results and have the potential to bring about significant changes in social, institutional, and cultural contexts [61].

In summary, entrepreneurship education aims to cultivate individuals with entrepreneurial mindsets, capabilities, and propensities, recognizing their broader applicability in diverse organizational contexts. This emphasis on developing enterprising individuals acknowledges the economic impact of nurturing individuals who can contribute to organizational performance and competitiveness [62].

The research conducted in various regions, including Mexico, Slovenia, Chile, and others, consistently indicates the crucial role of entrepreneurship education in nurturing entrepreneurial attitudes, skills, and competencies. By engaging young learners in practical entrepreneurial activities and providing support systems, educational institutions can empower students to make positive contributions to their communities and drive positive change through their chosen professions. As emphasized by Aral and Kılıçoğlu, integrating sustainable entrepreneurship education from an early age is vital in shaping an entrepreneurial mindset and preparing future generations for a rapidly changing economic landscape [45].

Limitations of This Study

Among the limitations of this study, we can highlight the difficulty in locating the children or young individuals who had participated in this program. Ideally, there should be a pre-established registration process before commencing a practical EE program to identify participants. Additionally, employing both pre-tests and multiple post-tests could offer insights into progress over the medium and long term. Moreover, designing instruments that can be captured and interpreted using statistical programs to create structural equation models might provide more comprehensive analysis results.

Author Contributions

Methodology, A.M.-L.; Software, L.R.-L.; Validation, F.-Y.R.-A. and L.R.-L.; Formal analysis, F.-Y.R.-A. and L.R.-L.; Investigation, F.-Y.R.-A., L.R.-L. and A.M.-L.; Writing—original draft, F.-Y.R.-A.; Writing—review & editing, F.-Y.R.-A.; Supervision, A.M.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sarıkaya, M.; Coşkun, E. A new approach in preschool education: Social entrepreneurship education. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, P.; Singh, S.K.; Awasthi, A. Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education Institutions: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A. Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.; Hill, F.; Leitch, C. Entrepreneurship education and training: Can entrepreneurship be taught? Part I. Educ. + Train. 2005, 45, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra-Pons, P.; Calatayud, C.; Garzón, D. A review of entrepreneurship education research and practice. J. Manag. Bus. Educ. 2022, 5, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, F.; Figueiredo, J.; Krueger, N. Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 687–725. [Google Scholar]

- Zunino, D. Influence of genetic factors and institutional environment on entrepreneurial activity: Evidence from a twin study in Italy. Ind. Corp. Change 2022, 31, 681–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuechle, G. The contribution of behavior genetics to entrepreneurship: An evolutionary perspective. J. Evol. Econ. 2019, 29, 12631284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Micro, Pequeña, Mediana y Gran Empresa. Estratificación de los Establecimientos; INEGI: CDMX, México, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía INEGI. Encuesta Nacional Sobre Productividad y Competitividad de Las Micro, Pequeñas y Medianas Empresas. 2015. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enaproce/2015/ (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Ramírez Calvillo, R.; Ramírez Berumen, I.E.; Acero Soto, I.O. La cultura emprendedora y los proyectos financiados por remesas en Zacatecas. Cienc. Adm. 2013, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Burin, D. Proyecto Jóvenes Emprendedores Rurales: Manual del Capacitador; Instituto para la Inclusión Social y el Desarrollo Humano: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, A.B.; Gutiérrez, A.C. La formación de emprendedores en la escuela y su repercusión en el ámbito personal. Una investigación narrativa centrada en el Programa EME. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2014, 72, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois, A.; Balcon, M.P.; Riiheläinen, J.M. Entrepreneurship Education at School in Europe. Eurydice Report; Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Likar, B.; Cankar, F.; Zupan, B. Educational Model for Promoting Creativity and Innovation in Primary Schools. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2015, 32, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarda, A.M.; Madrigal, D.F.; Flores, M.T. Factors associated with learning management in Mexican micro-entrepreneurs. Estud. Gerenciales 2016, 32, 381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Damián, J. Sistematizando experiencias sobre educación en emprendimiento en escuelas de nivel primaria. Rev. Mex. De Investig. Educ. 2013, 18, 159–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dehter, M. Responsabilidad Social de las Universidades Hisponoamericanas Para la Animación de la Cultura Emprendedora Regional; Universidad Nacional de San Martín: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bunk, G.P. La transmisión de las competencias en la formación y perfeccionamiento profesionales de la RFA (Asociación de Estudios sobre el Trabajo y la Organización de Empresas). Rev. Eur. Form. Prof. 1994, 1, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, F.M. Análisis de Competencias Emprendedoras del Alumnado de las Escuelas Taller y Casas de Oficios en Andalucía. Primera fase del diseño de Programas Educativos para el Desarrollo de la Cultura Emprendedora Entre los Jóvenes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy, M.; Kiely, T. Competencies: A New Sector. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2002, 26, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, N. The New Prescription for Performance: The Eleventh Competency Benchmarking Survey; Competency & Emotional Intelligence Benchmarking Supplement 2004/2005; IRS: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea, EACEA/Eurydice. La educación Para el Emprendimiento en los Centros Educativos en Europa. Informe de Eurydice; Oficina de Publicaciones de la Unión Europea: Luxemburgo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hytti, U.; O’Gorman, C. What is ‘enterprise education’? An analysis of objetives and methods of enterprise education programmes in four European countries. Educ. + Train. 2004, 46, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Europea (CE). Recomendación del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo Sobre Las Consecuencias Clave Para el Aprendizaje Permanente. Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea. 2006. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32006H0962 (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Comisión Europea (CE). Rethinking Education: Investing in Skills for Better Socio-Economic Outcomes; Comisión Europea (CE): Estrasburgo, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ladeveze, L.N.; Canal, M.N. Noción de emprendimiento para una formación escolar en competencia emprendedora. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2016, 71, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, L.; Vásquez, C. Evolución del concepto de emprendedor: De Cantillón a Freire. Rev. Digit. Investig. Postgrado 2015, 5, 882–894. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, A. Pasión Por Emprender, 2nd ed.; Grupo Editorial Norma: Bogotá, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Noworatzky, J. Tesis Experiential Learning and Its Impact on Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention in Two Innovative High School Programs. Ph.D. Thesis, College of Professional Studies Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.C.; Ward, A.; Hernández, B.; Flores, J. Educación emprendedora: Estado del arte. Propósitos Represent. 2017, 5, 401–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Europea (CE). Plan de Acción Sobre Emprendimiento 2020, Relanzar el Espíritu Emprendedor en Europa Bruselas. Recuperado de 2013. Available online: http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2012:0795:FIN:ES:PDF (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Volkmann, C.K.; Wilson, K.E.; Mariotti, S.; Rabuzzi, D. Educating the Next Wave of Entrepreneurs: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Capabilities to Meet the Global Challenges of the 21st Century; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackéus, M. Entrepreneurship in Education; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, M.I.; Fernandes, D.; Serrão, C.; Mascarenhas, D. Youth start social entrepreneurship program for kids: Portuguese UKIDS-case study. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2019, 10, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likar, D.; Juhart, M.; Kostevc, Č. Entrepreneurial Skills Development in Slovenian Primary Schools: The Impact of the HEIRRI Project. In Global Entrepreneurial Trends in the 21st Century 2015. Yaakob, J.C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 67–89.

- Kuratko, D.F. The Emergence of Entrepreneurship Education: Development, Trends, and Challenges. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, R.I.; Cobos, P.L. Entrepreneurship Education in Primary School: Fostering an Entrepreneurial Mindset. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2022, 18, e00281. [Google Scholar]

- Damian, R.I.; Simón, M. Entrepreneurship Education in Early Childhood: Fostering Entrepreneurial Skills in Young Learners. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 82, 101315. [Google Scholar]

- De Lourdes Cárcamo-Solís, M.; del Pilar Arroyo-López, M.; del Carmen Alvarez-Castañón, L.; García-López, E. Developing entrepreneurship in primary schools. The Mexican experience of “My first enterprise: Entrepreneurship by playing”. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 64, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, V.; Sevilla, J.F.; Ramírez, J. My First Business: Entrepreneurship through Play; Foundation for Higher Education-Business (FESE): CDMX, México, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, M. Learning to be Enterprising: A Study of School Entrepreneurship Education. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastiti, M.S.; Widjaja, S.U.M.; Handayati, P. The Role Of Self-Efficacy In Mediating The Effect Of Entrepreneurship Education, Economic Literacy And Family Environment On Entrepreneurial Intentions For Vocational School Students In Jember Regency. South East Asia Journal of Contemporary Business. Econ. Law 2021, 24, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Aral, N.; Kiliçoğlu, E.A. Sustainable entrepreneurship education “early childhood”. Generations 2022, 2, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn, S. Advancing entrepreneurs hip in an elementary school: A case study. Int. Educ. Stud. 2010, 3, 174–184. Available online: http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ies/article/viewFile/5886/4658 (accessed on 19 May 2019). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kolvereid, L.; Isaksen, E. New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 866–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise education: Influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanevenhoven, J.; Liguori, E. The impact of entrepreneurship education: Introducing the entrepreneurship education project. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.; Perez, J.P.; Novoa, S. Developing orientation to achieve entrepreneurial intention: A pretest-post-test analysis of entrepreneurship education programs. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A. Entrepreneurship and small business management: Can we afford to neglect them in the twenty-first century business school? Br. J. Manag. 1996, 7, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskovaara, E.; Pihkala, T. Entrepreneurship education in schools: Empirical evidence on the teacher’s role. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 108, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. Available online: http://www.inegi.org.mx/ (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Lucero, I.; Meza, S.; Validación de Instrumentos Para Medir Conocimientos. Departamento de Física—Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales y Agrimensura—UNNE. 2002. Available online: https://studylib.es/doc/4644001/validaci%C3%B3n-de-instrumentos-para-medir-conocimientos (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Gobierno del Estado de Baja California. Programa Para la Atención de la Región de San Quintín 2015–2019. Recuperado de 2017. Available online: http://www.copladebc.gob.mx/programas/regionales/Programa%20para%20la%20Atencion%20de%20la%20Region%20de%20San%20Quintin%202015-2019.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Oe, H.; Tanaka, C. Qualitative Evaluation of Scaffolded Teaching Materials in Business Analysis Classes: How to Support the Learning Process of Young Entrepreneurs. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, C.E.C.; González, L.E.C.; Olvera MDL Á, S.; Rodríguez, M.D.C.L. El espíritu emprendedor y un factor que influencia su desarrollo temprano. Concienc. Tecnológica 2015, 49, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Youth Start (YS). Se Consultaron Varios Documentos en. 2019. Available online: http://www.youthstart.eu/en/sitioofficial, (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Denegri, M.; Sepúlveda, L. Me and the Economy: Fostering Entrepreneurial Mindsets from an Early Age. Liberabit 2014, 20, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rindova, V.; Barry, D.; Ketchen, D. Introduction to special topic forum: Entrepreneuring as emancipation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, A.; Wraae, B. Entrepreneurship education but not as we know it: Reflections on the relationship between Critical Pedagogy and Entrepreneurship Education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).