Autistic Adult Knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Employment-Related Rights

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Advocacy

1.2. The ADA and Workplace Rights

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Setting and Materials

Test Scenarios

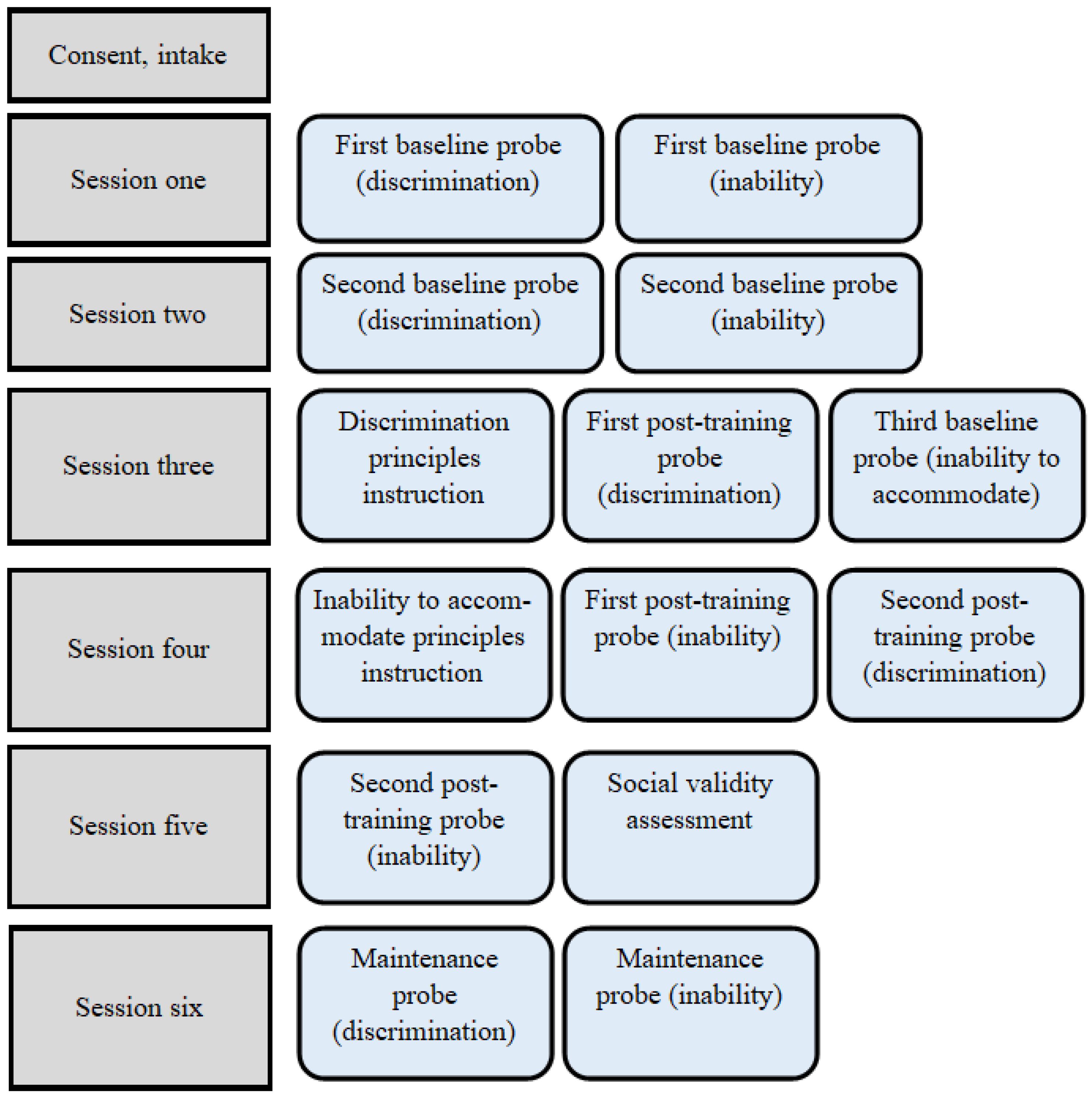

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Independent Variable

2.5. Dependent Variable

2.6. Interobserver Agreement

2.7. Procedure

2.7.1. Baseline

2.7.2. Instruction: Discrimination Training

2.7.3. Instruction for Inability to Accommodate Training

2.7.4. Second Post-Training Probe of Inability to Accommodate

2.7.5. Social Validity

2.7.6. Maintenance

3. Results

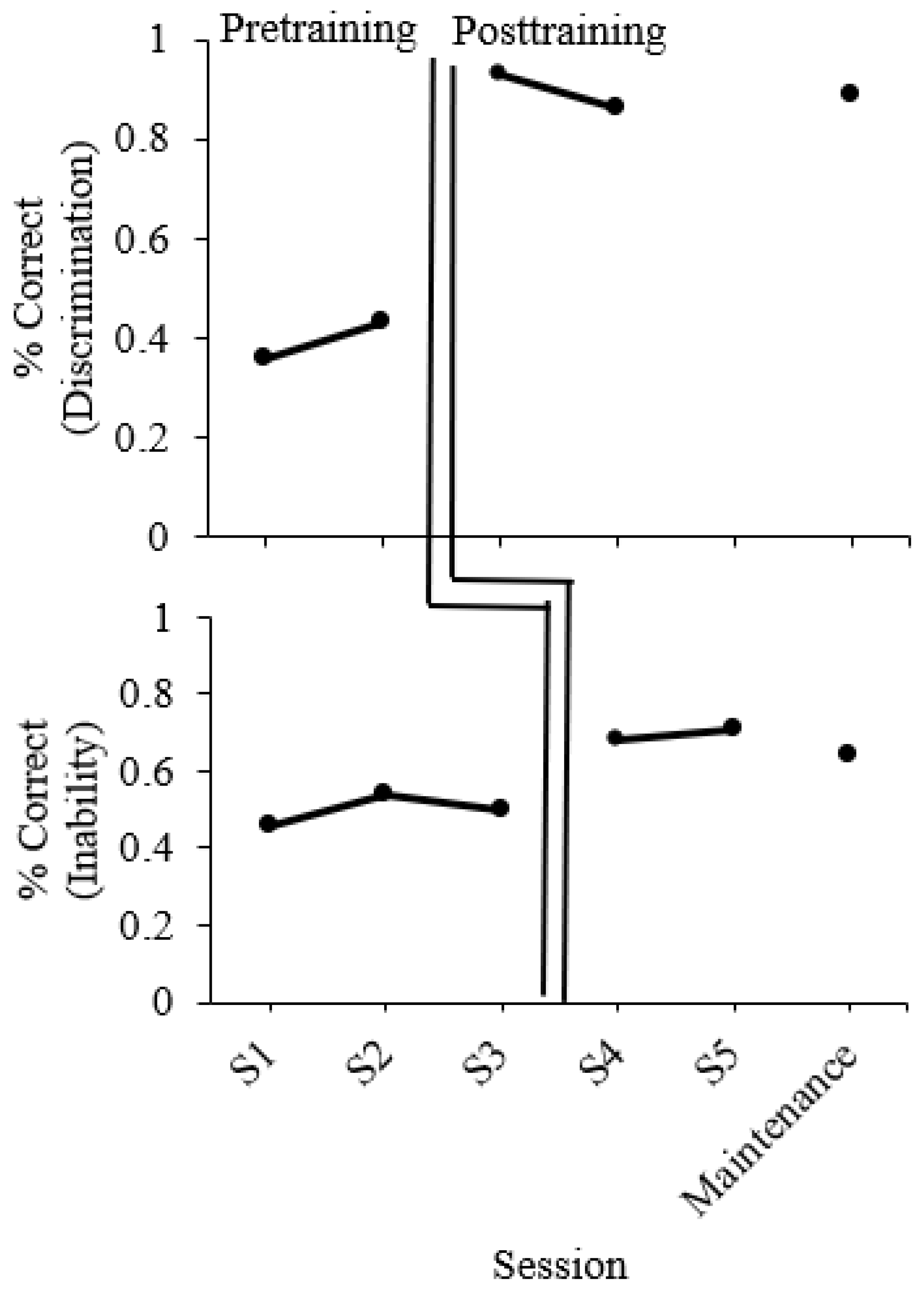

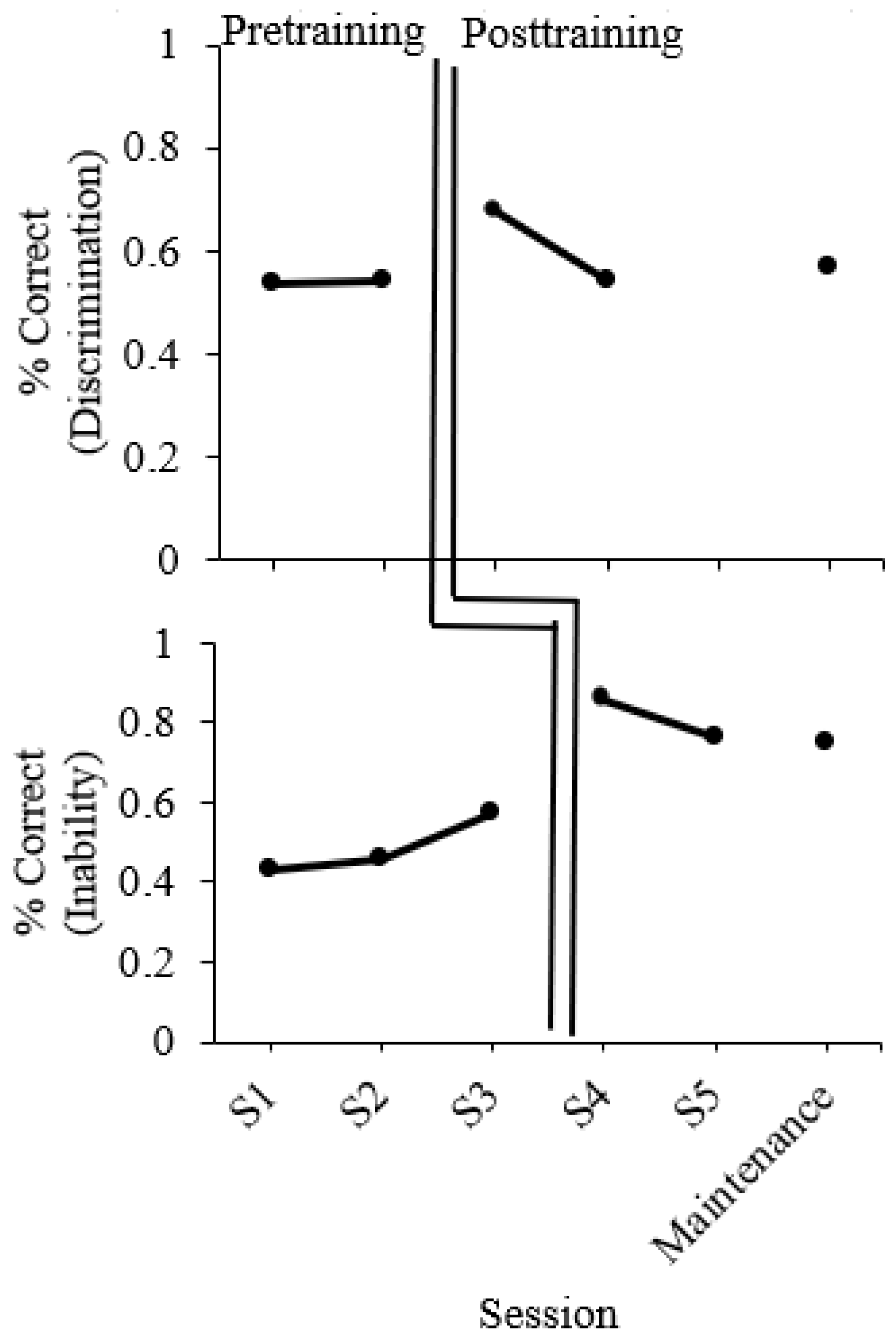

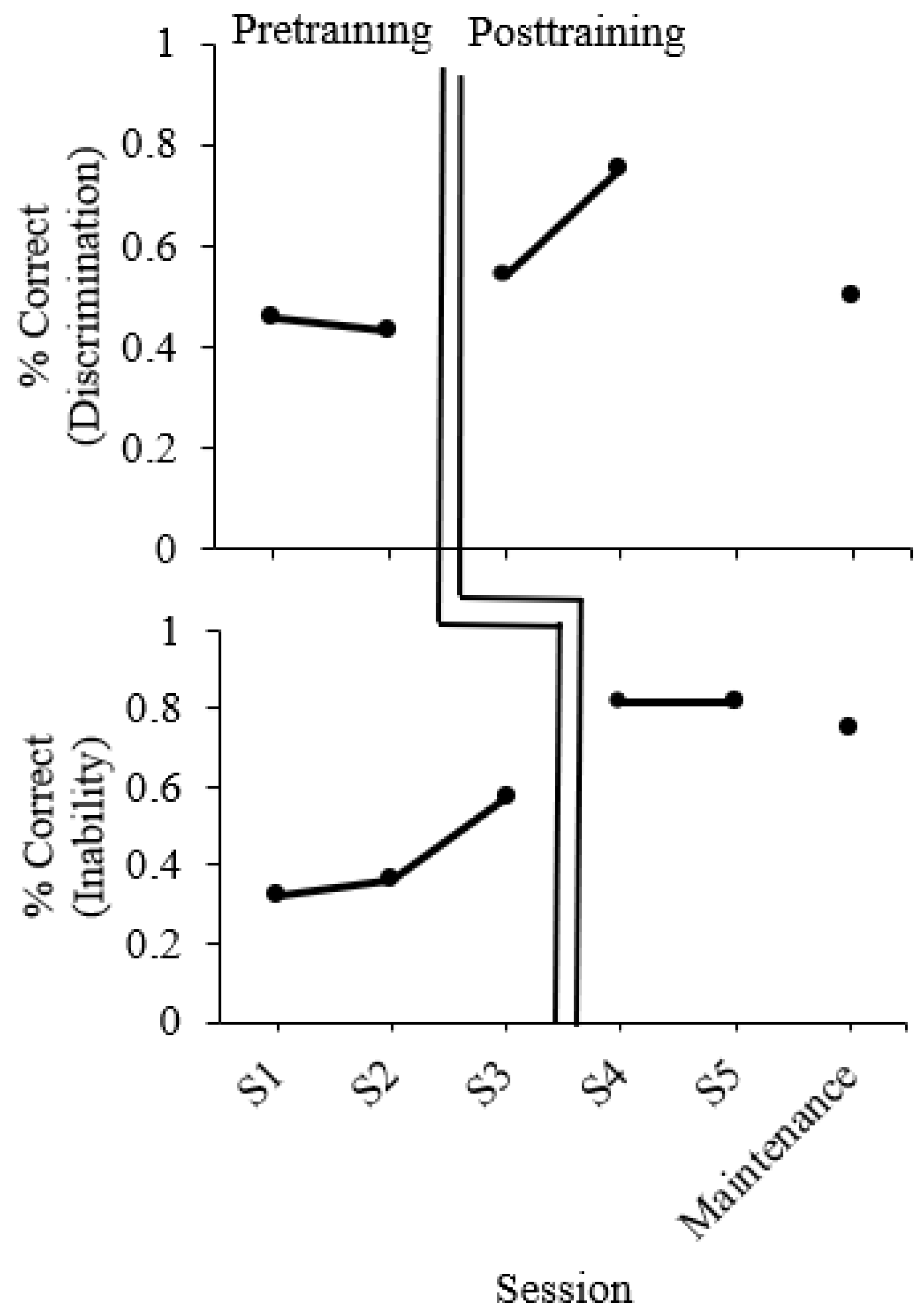

3.1. Probe Performance

3.2. Item Analysis

3.3. Social Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Scenarios (Employment Discrimination)

- 1.

- Principle: Refusal of accommodation

- a.

- Faysal works at the police station, where he works as a dispatcher. Due to the nature of his status as an autistic individual, Faysal has recently requested an accommodation to reduce the number of hours he works; however, this request has been denied, with the stated reason being that this would highlight his disability status.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Highlight disability status.

- b.

- Faysal works at the police station, where he works as a dispatcher. Due to the nature of his status as an amputee (left arm), Faysal has recently requested an accommodation to reduce the number of hours he works; however, this request has been denied, with the stated reason being that this would conflict with an essential job requirement.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Conflicts with essential job requirement.

- 2.

- Principle: Retaliation

- a.

- Natalya works at a local university where she serves as a financial officer paid by the hour. Due to her experience with social anxiety, she recently requested accommodation to work from home. Accordingly, she received her requested accommodation and reduced hours worked overall.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Reduction in work hours results in lower pay unrelated to accommodation.

- b.

- Natalya works at a local university where she serves as a financial officer paid by the hour. Due to her experience with social anxiety, she recently requested accommodation to work from home. Accordingly, she received her requested accommodation and tends to see her colleagues less often.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Social interactions with colleagues does not reduce most important work aspects.

- 3.

- Principle: Direct threat

- a.

- Rohit works at a local high school where he works as a chemistry teacher. However, due in part to his experience with PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), one day during work he experiences a surprising burst of anger, during which he flings an object at a student and causes an injury. His superior notifies him that he constitutes a direct threat to his students and coworkers and that he will be let go. Rohit suggests that instead, he could be given accommodation to teach virtually. He is still let go shortly afterwards.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Presents direct threat, accommodation would conflict with core teaching responsibilities (being physically present).

- b.

- Rohit works at a local high school where he works as a chemistry teacher. Rohit is also HIV positive. One day during work he is cut and, without his knowledge, spreads droplets of blood around the chemistry lab. His superior notifies him that he constitutes a direct threat to his students and coworkers and that he will be let go. Rohit suggests that instead, he could be given accommodation to not work with sharp objects or open flames. He is still let go shortly afterwards.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Presents direct threat, could be controlled with reasonable accommodation.

- 4.

- Principle: Reassignment

- a.

- Jerome is working as a lead program developer. However, recent events have caused him to officially register with his employer as having a major depressive disorder. Sometime afterwards, Jerome requests reassignment within his employment, specifically to work as a lead app developer, as the work is more to his liking. His employer denies him an automatic transfer based on disability status and instead states that he must compete for the position internally.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Transfer based on preference, not disability status; transfer position is likely to be in competition.

- b.

- Jerome is working as a park ranger. However, recent events have caused him to officially register with his employer as having arthritis. Sometime afterwards, Jerome requests reassignment within his employment, specifically to work as the local natural museum attendant, as the arthritis is disrupting his ability to work in the field. His employer denies him an automatic transfer based on disability status and instead states that he must compete for the position internally.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Transfer based on disability status; transfer position unlikely to be in competition.

- 5.

- Principle: Interviewing

- a.

- Fatima is applying for a position as a computer programmer. As per her experience with major depressive disorder, she requests to have an alternative to a job interview, as she thinks that needing to interview will unfairly disadvantage her. The employer declines to offer the alternative, stating that the interview is an important part of the application and selection process.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Contents of interview unlikely to be assessing essential job functions, given job.

- b.

- Fatima is applying for a position as a computer programmer. As per her experience with visual impairment, she requests to have an alternative to a job interview, as she thinks that needing to interview will unfairly disadvantage her. The employer declines to offer the alternative, stating that the interview is an important part of the application and selection process.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Contents of interview unlikely to be assessing essential job functions, given job.

- 6.

- Principle: Exacerbating a condition

- a.

- Santiago works as a professor and has recently acquired and disclosed arthritis. However, he is soon asked to perform a new task, teaching on the ground floor of a new building, as the elevator in this building is not working. Santiago then proceeds to teach the class as assigned.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Assignment has low chance of exacerbating Santiago’s arthritis.

- b.

- Santiago works as a professor and has recently acquired and disclosed a social anxiety diagnosis. However, he is soon asked to perform a new task, teaching an online class of 55 students three times weekly, as meeting digitally is easier on his social anxiety. He then proceeds to teach the class as assigned.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Assignment has low chance of exacerbating Santiago’s arthritis.

- 7.

- Principle: Timing of disclosure

- a.

- Mia has just applied for a job to work as a shipping and receiving staff member. Mia also has epilepsy but does not disclose this during the application process. When Mia is offered the position, she accepts. The job initially proves difficult due to her epilepsy, but Mia does not disclose her disability status and continues to work.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Mia did not disclose; not responsibility of employer to accommodate non-salient disability.

- b.

- Mia has just applied for a job to work as a shipping and receiving staff member. Mia also has epilepsy but does not disclose this during the application process. When Mia is offered the position, she accepts. The job initially proves difficult due to her epilepsy, whereupon she discloses her diagnosis and receives accommodation based on her disability status.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Upon disclosure, Mia is accommodated.

- 1.

- Faysal works at the police station, where he works as a dispatcher. Due to the nature of his status as an amputee (left arm), Faysal has recently requested an accommodation to reduce the number of hours he works; however, this request has been denied, with the stated reason being that this would increase the risk of workplace bullying and ostracism.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Cannot decline due to fear of worker experience.

- 2.

- Natalya works at a local hospital where she serves as a surgeon. Due to her experience with diabetes, she recently requested accommodation to have shorter and less intensive operations. Accordingly, she received her requested accommodation and tends to work with different types of operations than she did before.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Core features of Natalya’s employment experience preserved.

- 3.

- Rohit works at a local high school where he works as a chemistry teacher. However, due in part to his experience with PTSD, one day during work he experiences an anxiety attack, during which a fire in the lab starts. His superior notifies him that he constitutes a direct threat to his students and coworkers and that he will be let go. Rohit suggests that instead, he could be given accommodation to not work with chemicals or open flames. He is still let go shortly afterwards.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Direct threat may exist, could be controlled by stated accommodation.

- 4.

- Jerome is working as a lead program developer. However, recent events have caused him to officially register with his employer as having a major depressive disorder. Sometime afterwards, Jerome requests reassignment within his employment, specifically to work as an assistant app developer, as the schedule is less demanding. His employer denies him an automatic transfer based on disability status and instead states that he must compete for the position internally.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Transfer based on disability status; transfer position unlikely to be in competition.

- 5.

- Fatima is applying for a position as an automobile salesperson. As per her experience with major depressive disorder, she requests to have an alternative to a job interview, as she thinks that needing to interview will unfairly disadvantage her. The employer declines to offer the alternative, stating that the interview is an important part of the application and selection process.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Interview likely evaluates essential functions (social skill) of position.

- 6.

- Santiago works as a professor and has recently acquired and disclosed arthritis. However, he is soon asked to perform a new task, teaching on the fourth floor of a new building, which he thinks will be especially hard for him thanks to his arthritis, as the elevator in this building is not working. He asks for a reassignment to teach on the ground floor of the building, which is then refused.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Assignment likely to exacerbate arthritis, accommodation would preserve essential functions.

- 7.

- Mia has just applied for a job to work as a shipping and receiving staff member. Mia is also autistic with sensory sensitivity but does not disclose this during the application process. When Mia is offered the position, she accepts. The job initially proves difficult due to her sensory sensitivity, whereupon she discloses her diagnosis and receives accommodation based on her disability status.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Did not disclose non-obvious disability; accommodated upon disclosure.

- 1.

- Faysal works at the police station, where he works as a dispatcher. Due to the nature of his status as an autistic individual, Faysal has recently requested an accommodation to reduce the number of hours he works; however, this request has been denied, with the stated reason being that this would conflict with an essential job requirement.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Conflicts with essential job requirement.

- 2.

- Natalya works at a local hospital where she serves as a surgeon. Due to her experience with diabetes, she recently requested accommodation to have shorter and less intensive operations. Accordingly, she received her requested accommodation and a reduced number of clients received overall.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Reduction in opportunity to work without clear explanation.

- 3.

- Rohit works at a local high school where he works as a chemistry teacher. Rohit is also HIV positive. One day during work he must physically restrain a student, during which he is cut and his blood drips onto the floor. His superior notifies him that he constitutes a direct threat to his students and coworkers and that he will be let go. Rohit suggests that instead, he could be given accommodation to not have to physically confront students. He is still let go shortly afterwards.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Restraint likely not essential job function.

- 4.

- Jerome is working as a park ranger. However, recent events have caused him to officially register with his employer as having arthritis. Sometime afterwards, Jerome requests reassignment within his employment, specifically to work as the local natural museum attendant, as the work is more to his liking. His employer denies him an automatic transfer based on disability status and instead states that he must compete for the position internally.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Transfer based on preference, not disability status.

- 5.

- Fatima is applying for a position as an automobile salesperson. As per her experience with visual impairment, she requests to have an alternative to a job interview, as she thinks that needing to interview will unfairly disadvantage her. The employer declines to offer the alternative, stating that the interview is an important part of the application and selection process.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Interview likely evaluates essential functions (social skill) of position.

- 6.

- Santiago works as a professor and has recently acquired and disclosed a social anxiety diagnosis. However, he is soon asked to perform a new task, teaching a class of 55 students three times weekly. He thinks it will be especially hard for him thanks to his social anxiety. He asks for a reassignment to teach an online course instead, which is then refused.

- i.

- Answer: Likely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Assignment likely to exacerbate arthritis, accommodation would preserve essential functions.

- 7.

- Mia has just applied for a job to work as a shipping and receiving staff member. Mia is also autistic with sensory sensitivity but does not disclose this during the application process. When Mia is offered the position, she accepts. The job initially proves difficult due to her sensory sensitivity, but Mia does not disclose her disability status and continues to work.

- i.

- Answer: Unlikely to be discrimination

- ii.

- Key information: Mia did not disclose; not responsibility of employer to accommodate non-salient disability.

Appendix B. Scenarios (Inability to Accommodate)

- 1.

- Principle: Prolonged absence

- a.

- Fernando is a worker with diabetes who recently left to get an important operation with a recovery period of two weeks. His employer reassigned tasks to cover for him while he was absent. The operation was successful, but a complication ensures that Fernando’s recovery will be longer than expected. Specifically, Fernando’s doctors say that he will be able to return after four weeks rather than two. Fernando accordingly notifies his job and uses his saved sick and medical leave to cover the difference.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Clear leave period, covering with existing leave.

- b.

- Fernando is a worker with epilepsy who recently left to get an important operation with a recovery period of two weeks and has used up all his sick and medical leave to cover this two-week period. The operation was successful, but a complication ensures that Fernando’s recovery will be longer than expected. Specifically, Fernando’s doctors are not able to provide a time that Fernando would be medically able to return. Fernando accordingly notifies his job and asks for his leave to be extended accordingly based on his disability status.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Unclear leave period, non-use of employee coverage.

- 2.

- Principle: Removal of essential job functions

- a.

- Mikael is a retail store clerk with a disclosed social anxiety diagnosis. He asks for accommodation based on his disability status to not have to advertise company programs during client checkouts.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Preserves essential functions.

- b.

- Mikael is a home repair electrician with a disclosed arthritis diagnosis. He asks for accommodation based on his disability status to receive additional tools to minimize bending over during work.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Preserves essential functions (may increase ability).

- 3.

- Principle: Facility operation

- a.

- Jamal is a project manager with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), who needs to be present at a project for it to begin. According to the nature of his disability, he requests accommodation that the traditional project supervisors’ meeting start at 10:00 a.m. instead of 9:00 a.m., such that he can be certain he will always be present for the start of the meeting.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: “Traditional” meeting timing unlikely to be essential.

- b.

- Jamal is a project manager who uses a wheelchair, who needs to be present at a project for it to begin. According to the nature of his disability, he requests accommodation that shifts start at 10:00 a.m. instead of 9:00 a.m., such that he can be certain he will always be present for the start of work on the project.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Start of work shift likely to be essential.

- 4.

- Principle: Infringing on rights of other workers

- a.

- Robbie is a worker with lupus. In his job as a CNC machinist, Robbie is trained at a key point in the process. However, due to his experience of lupus, Robbie asks for accommodation wherein he can begin his shift up to 15 min later than usual, based on how his symptoms are progressing that day. Due to the nature of this position, other workers will arrive but will still be paid before Robbie arrives and the process can resume.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Not causing loss of others’ pay.

- b.

- Robbie is a worker with bipolar disorder. In his job as a CNC machinist, Robbie is trained at a key point in the process. However, due to his experience of bipolar, Robbie asks for accommodation wherein he can begin his shift up to a half-hour later than usual, based on how his symptoms are progressing that day. Due to the nature of this position, other workers will arrive but will not be paid until Robbie arrives and the process can resume.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Causing loss of others’ pay.

- 5.

- Principle: Financial ability of the employer

- a.

- René is a retail store associate who is legally blind due to macular degeneration. As René is otherwise qualified to work, René asks for the materials produced for employees (such as the employee handbook and any other written employee documents or messages) to also be produced in Braille so that she has a reference for it. Her employer, who produces an average yearly profit of $100,000, is currently deciding if it is in their ability to meet this request as it would have an estimated cost of approximately $5000.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: High cost, financial ability to cover.

- b.

- René is a retail store associate who is legally blind due to her experience of a stroke. As René is otherwise qualified to work, René asks for the materials produced for employees (such as the employee handbook and any other written employee documents or messages) to also be produced in Braille so that she has a reference for it. Her employer, who produces an average yearly profit of $10,000, is currently deciding if it is in their ability to meet this request as it would have an estimated cost of approximately $5000.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: High cost, lack of financial ability to cover.

- 6.

- Principle: Persistent refusal of accommodation

- a.

- Bridget is a worker with major depressive disorder who is pursuing a workplace accommodation for a non-essential job function. Bridget has suggested accommodation that, while likely to be successful, is out of the range of what the employer can do. Their employer has suggested three other accommodation that would address Bridget’s stated accommodation needs; however, Bridget has declined to accept these accommodations in favor of her suggestion.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Accommodation targets non-essential job function.

- b.

- Bridget is a worker with muscular dystrophy who is pursuing a workplace accommodation for a non-essential job function. Bridget has suggested accommodation that, while likely to be successful, is out of the range of what the employer can do. Their employer has suggested one other accommodation that would address Bridget’s stated accommodation needs; however, Bridget has declined to accept these accommodations in favor of her suggestion.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Accommodation targets non-essential job function.

- 7.

- Principle: Workplace redesign

- a.

- Donovan is applying to work at a small mechanic shop. However, Donovan discloses that he has an auditory sensitivity due to his personal experience with autism and asks if he could have accommodation to reduce noise in his workspace. The employer’s HR representative suggests that workers should regularly attend to shop machines to prevent unusual loud noises.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Ongoing redesign, demands on other workers.

- b.

- Donovan is applying to work at a small mechanic shop. However, Donovan discloses that he has an auditory sensitivity due to his personal experience with a recent concussion and asks if he could have accommodation to reduce noise in his workspace. The employer’s HR representative suggests that Donovan could use noise-cancelling headphones during his shifts.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Redesign not necessary, no demands on other workers.

- 1.

- Fernando is a worker with diabetes who recently left to get an important operation with a recovery period of two weeks. His employer reassigned tasks to cover for him while he was absent. The operation was successful, but a complication ensures that Fernando’s recovery will be longer than expected. Specifically, Fernando’s doctors say that he will be able to return after four weeks rather than two. Fernando accordingly notifies his job and uses the rest of his sick and medical leave to cover the difference.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Clear leave period, covering with existing leave.

- 2.

- Mikael is a retail store clerk with a disclosed social anxiety diagnosis. He asks for accommodation based on his disability status to not have to advertise company programs during client checkouts.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Preserves essential functions.

- 3.

- Jamal is a project manager with ADHD, who needs to be present at a project for it to begin. According to the nature of his disability, he requests accommodation that shifts start at 10:00 a.m. instead of 9:00 a.m., such that he can be certain he will always be present for the start of work on the project.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Start of work shift likely to be essential.

- 4.

- Robbie is a worker with lupus. In his job as a CNC machinist, Robbie is trained at a key point in the process. However, due to his experience of lupus, Robbie asks for accommodation wherein he can begin his shift up to 15 min later than usual, based on how his symptoms are progressing that day. Due to the nature of this position, other workers will arrive but will not be paid until Robbie arrives and the process can resume.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Not causing loss of others’ pay.

- 5.

- René is a retail store associate who is legally blind. As René is otherwise qualified to work, René asks for the materials produced for employees (such as the employee handbook and any other written employee documents or messages) to also be produced in Braille so that she has a reference for it. Her employer, who produces an average yearly profit of $10,000, is currently deciding if it is in their ability to meet this request as it would have an estimated cost of approximately $5000.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: High cost, lack of financial ability to cover.

- 6.

- Bridget is a worker with major depressive disorder who is pursuing a workplace accommodation so that she can perform an essential job function. Bridget has suggested accommodation that, while likely to be successful, is out of the range of what the employer can do. Their employer has suggested one other accommodation that would address Bridget’s stated accommodation needs; however, Bridget has declined to accept these accommodations in favor of her suggestion.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Accommodation targets essential job function Bridget cannot perform, is not reasonable.

- 7.

- Donovan is applying to work at a small mechanic shop. However, Donovan discloses that he has an auditory sensitivity due to his personal experience with autism and asks if he could have accommodation to reduce noise in his workspace. The employer’s HR representative suggests that Donovan could use noise-cancelling headphones during his shifts.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Redesign not necessary, no demands on other workers.

- 1.

- Fernando is a worker with diabetes who recently left to get an important operation with a recovery period of two weeks. His employer reassigned tasks to cover for him while he was absent. The operation was successful, but a complication ensures that Fernando’s recovery will be longer than expected. Specifically, Fernando’s doctors are not able to provide a time that Fernando would be medically able to return. Fernando accordingly notifies his job and asks for his leave to be extended accordingly.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Unclear leave period, non-use of employee coverage.

- 2.

- Mikael is a home repair electrician with a disclosed arthritis diagnosis. He asks for accommodation based on his disability status to identify electrical issues but not fix them if it would require bending over.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Conflicts with essential functions.

- 3.

- Jamal is a project manager who uses a wheelchair, who needs to be present at a project for it to begin. According to the nature of his disability, he requests accommodation that the traditional project supervisors’ meeting start at 10:00 a.m. instead of 9:00 a.m., such that he can be certain he will always be present for the start of the meeting.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: “Traditional” project meeting time unlikely to be essential.

- 4.

- Robbie is a worker with bipolar disorder. In his job as a CNC machinist, Robbie is trained at a key point in the process. However, due to his experience of bipolar, Robbie asks for accommodation wherein he can begin his shift up to a half-hour later than usual, based on how his symptoms are progressing that day. Due to the nature of this position, other workers will arrive but will still be paid until Robbie arrives and the process can resume.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Causing loss of others’ pay.

- 5.

- René is a retail store associate who is dyslexic. As René is otherwise qualified to work, René asks for the materials produced for employees (such as the employee handbook and any other written employee documents or messages) to also be produced in Braille so that she has a reference for it. Her employer, who produces an average yearly profit of $100,000, is currently deciding if it is in their ability to meet this request as it would have an estimated cost of approximately $5000.

- i.

- Answer: Could accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: High cost, financial ability to cover.

- 6.

- Bridget is a worker with muscular dystrophy who is pursuing a workplace accommodation for an essential job function. Bridget has suggested accommodation that, while likely to be successful, is out of the range of what the employer can do. Their employer has suggested three other accommodation that would address Bridget’s stated accommodation needs; however, Bridget has declined to accept these accommodations in favor of her suggestion.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Accommodation targets essential job function Bridget cannot perform, is not reasonable.

- 7.

- Donovan is applying to work at a small mechanic shop. However, Donovan discloses that he has an auditory sensitivity due to his personal experience with a recent concussion and asks if he could have accommodation to reduce noise in his workspace. The employer’s HR representative suggests that workers should regularly attend to shop machines to prevent unusual loud noises.

- i.

- Answer: Could not accommodate

- ii.

- Key information: Ongoing redesign, demands on other workers.

Appendix C. Social Validity Questionnaire

- 1.

- How well do you think our style of teaching taught you the information?

- a.

- Very poorly

- b.

- Somewhat poorly

- c.

- A little poorly

- d.

- I am not sure.

- e.

- A little well

- f.

- Somewhat well

- g.

- Very well

- 2.

- How did you like the number of study sessions?

- a.

- There were far too many sessions.

- b.

- There were a few too many sessions.

- c.

- I liked the number of sessions used.

- d.

- There were a few too many sessions.

- e.

- There were far too many sessions.

- 3.

- How did you like the length of study sessions?

- a.

- They were much too long.

- b.

- They were a little too long.

- c.

- I liked the length as it was.

- d.

- They were a little too short.

- e.

- They were much too short.

- 4.

- How well did you like the timing of sessions (how we met once or twice a week)?

- a.

- I wish that we had met much less often.

- b.

- I wish that we had met a little less often.

- c.

- I liked it as it was.

- d.

- I wish we had met a little more often.

- e.

- I wish we had met much more often.

- 5.

- How would you rate your knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act?

- a.

- Very little

- b.

- A little

- c.

- Some

- d.

- A lot

- e.

- Very much

- 6.

- How would you rate your knowledge of employment discrimination based on disability status?

- a.

- Very little

- b.

- A little

- c.

- Some

- d.

- A lot

- e.

- Very much

- 7.

- How would you rate your knowledge of inability to accommodate?

- a.

- Very little

- b.

- A little

- c.

- Some

- d.

- A lot

- e.

- Very much

- 8.

- Is there any additional feedback you would like to give us?

References

- Chen, J.L.; Leader, G.; Sung, C.; Leahy, M. Trends in employment for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the research literature. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, D. Employment and adults with autism spectrum disorders: Challenges and strategies for success. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Hedley, D.; Randolph, J.K.; Raymaker, D.M.; Robertson, S.M.; Vincent, J. An expert discussion on employment in autism. Autism Adulthood 2019, 1, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C. Autism and employment: Implications for employers and adults with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 4209–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittenburg, H.N.; Cimera, R.E.; Thoma, C.A. Comparing Employment Outcomes of Young Adults with Autism: Does Postsecondary Educational Experience Matter? J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2019, 32, 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cordell, A.T.; Flower, R.L.; Zulla, R.; Nicholas, D.B.; Hedley, D. Workplace social challenges experienced by employees on the autism spectrum: An international exploratory study examining employee and supervisor perspectives. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.J.; Taylor, J.; Berdyyeva, A.; McClelland, A.M.; Murphy, K.M.; Westbrook, J. Interventions for improving employment outcomes for persons with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review update. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2021, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmuth, E.; Silletta, E.; Bailey, A.; Adams, T.; Beck, C.; Barbic, S.P. Barriers and facilitators to employment for adults with autism: A scoping review. Ann. Int. Occup. Ther. 2018, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlin, P.; Magiati, I. Autism spectrum disorder: Outcomes in adulthood. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, V.; Brooke, A.M.; Schall, C.; Wehman, P.; McDonough, J.; Thompson, K.; Smith, J. Employees with autism spectrum disorder achieving long-term employment success: A retrospective review of employment retention and intervention. Res. Pr. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2018, 43, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, R.L.; Cannella-Malone, H.I. Vocational skills interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2016, 28, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, S.M.; Hedley, D.; Uljarević, M. Restricted, repetitive behaviours and interests in the workplace: Barriers, advantages, and an individual difference approach to autism employment. In Repetitive and Restricted Behaviors and Interests in Autism Spectrum Disorders; Gal, E., Yirmiya, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, C.; Kobylarz, A.; Zaki-Scarpa, C.; LaRue, R.H.; Manente, C.; Kahng, S. Differential reinforcement to decrease stereotypy exhibited by an adult with autism spectrum disorder. Behav. Interv. 2021, 36, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.G.; Carlson, J.I. Reduction of severe behavior problems in the community using a multicomponent treatment approach. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1993, 26, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S.M.; McVilly, K.R.; Stokes, M.A. Autism and employment: What works. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 60, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.D.; Joshi, A. Dark clouds or silver linings? A stigma threat perspective on the implications of an autism diagnosis for workplace well-being. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzeminska, A.; Austin, R.D.; Bruyère, S.M.; Hedley, D. The advantages and challenges of neurodiversity employment in organizations. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, C.M.; Henry, S.; Linthicum, M. Employability in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Job candidate’s diagnostic disclosure and ASD characteristics and employer’s ASD knowledge and social desirability. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2021, 27, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santuzzi, A.M.; Waltz, P.R.; Finkelstein, L.M.; Rupp, D.E. Invisible disabilities: Unique challenges for employees and organizations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 7, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M.T. How can the work environment be redesigned to enhance the well-being of individuals with autism? Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, L.A.; Mesibov, G.B. Perceptions of social challenges of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2005, 9, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, D.; Feeley, C.; Lubin, A. Travel patterns, needs, and barriers of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Report from a survey. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2016, 2542, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubin, A.; Feeley, C. Transportation issues of adults on the autism spectrum: Findings from focus group discussions. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2016, 2542, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.; Migliore, A.; Butterworth, J. Self-determination, social skills, job search, and transportation: Is there a relationship with employment of young adults with autism? J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2016, 45, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, R.; Remington, A. The strengths and abilities of autistic people in the workplace. Autism Adulthood 2022, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, E. Autism, attributions, and accommodations: Overcoming barriers and integrating a neurodiverse workforce. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.; Falkmer, M.; Girdler, S.; Falkmer, T. Viewpoints on factors for successful employment for adults with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, S.M.; Hedley, D.; Uljarević, M.; Dissanayake, C.; Gal, E. If you’ve employed one person with autism: An individual difference approach to the autism advantage at work. Autism 2018, 23, 1607–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bury, S.M.; Hedley, D.; Uljarević, M.; Gal, E. The autism advantage at work: A critical and systematic review of current evidence. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 105, 103750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, G.; Kapp, S.K.; Elliott, D.; Elphick, C.; Gwernan-Jones, R.; Owens, C. Mapping the autistic advantage from the accounts of adults diagnosed with autism: A qualitative study. Autism Adulthood 2019, 1, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, G.; Sharif, Z.; Sultan, M.; Di Rezze, B. Workplace accommodations for adults with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 42, 1316–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisman-Nitzan, M.; Gal, E.; Schreuer, N. It’s like a ramp for a person in a wheelchair”: Workplace accessibility for employees with autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 114, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.; Storey, K.; Post, M.; Lemley, J. The use of auditory prompting systems for increasing independent performance of students with autism in employment training. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2011, 34, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordell, A.T. Creating a Vocational Training Site for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2023, 10534512231156882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Cervantes, P.E.; Matson, J.L. Comorbid symptomology in adults with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 3961–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supekar, K.; Iyer, T.; Menon, V. The influence of sex and age on prevalence rates of comorbid conditions in autism. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test, D.W.; Fowler, C.H.; Wood, W.M.; Brewer, D.M.; Eddy, S. A conceptual framework of self-advocacy for students with disabilities. Remedial Spéc. Educ. 2005, 26, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbitter, K.; Buckle, K.L.; Ellis, C.; Dekker, M. Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: Implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ne’Eman, A.; Bascom, J. Autistic self advocacy in the developmental disability movement. Am. J. Bioeth. 2020, 20, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schena, D.; Rosales, R.; Rowe, E. Teaching self-advocacy skills: A review and call for research. J. Behav. Educ. 2022, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeire, T. The Americans with Disabilities Act and the employment of people with disabilities. In The Decline in Employment of People with Disabilities: A Policy Puzzle; Stapleton, D.C., Burkhauser, R.V., Eds.; W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2003; pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Jolls, C. Identifying the effects of the Americans with Disabilities Act using state-law variation: Preliminary evidence on educational participation effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- ADA.Gov. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, As Amended. 2023. Available online: https://www.ada.gov/law-and-regs/ada/ (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- US Department of Labor. Americans with Disabilities Act. 2023. Available online: https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/disability/ada (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Blanck, P. On the importance of the Americans with Disabilities Act at 30. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2021, 10442073211036900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Angrist, J.D. Consequences of Employment Protection? Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesel, L.R.; Dezelar, S.; Lightfoot, E. Equity in social work employment: Opportunity and challenge for social workers with disabilities in the United States. Disabil. Soc. 2019, 34, 1399–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Shin, J. The effect of the Americans with Disabilities Act on economic well-being of men with disabilities. Health Policy 2006, 76, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue III, J.J.; Stein, M.A.; Griffin, C.L., Jr.; Becker, S. Assessing post-ADA employment: Some econometric evidence and policy considerations. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 2011, 8, 477–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolin, T.; Patwell, M. A critique of economic analysis of the ADA. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2003, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Osten, V.; Rezai, M.; Bui, S. Disclosure and workplace accommodations for people with autism: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 43, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievert, A.L.; Cuvo, A.J.; Davis, P.K. Training self-advocacy skills to adults with mild handicaps. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1988, 21, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Skinner, R.; Martin, J.; Clubley, E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists, and mathematicians. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard-Brak, L.; Fearon, D.D. Self-advocacy skills as a predictor of student IEP participation among adolescents with autism. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2012, 47, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.M. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1978, 11, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant ID | Age (Years) | Ethnic Identity | Hispanic Cultural Origin | Gender Identity | Autism Diagnosis Received? | Autism Score (Out of 50) | Employed within the Past Year? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christa | 43 | Non-Hispanic White or European American | No | Nonbinary | Yes | 31 | No |

| Nate | 25 | Hispanic | Yes | Male | Yes | 29 | No |

| Justin | 20 | Non-Hispanic White or European American | Yes | Male | Yes | 24 | No |

| Discrimination-Related Principles | Inability to Accommodate-Related Principles |

|---|---|

| Refusal of Accommodation | Prolonged Absence |

| Retaliation | Removal of Essential Job Functions |

| Direct Threat | Facility Operation |

| Reassignment | Infringement on the Rights and Pay of Others |

| Interviewing | Financial Ability of the Employer |

| Exacerbating a Condition | Persistent Refusal of Accommodation |

| Timing of Disclosure | Workplace Redesign |

| Item | Christa | Nate | Justin | Average Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Discrimination | ||||

| Refusal of accommodation | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.42 |

| Retaliation | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.33 |

| Direct threat | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Reassignment | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.33 |

| Interviewing | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.35 |

| Exacerbating a condition | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Timing of disclosure | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Average | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.54 |

| Explanation | ||||

| Refusal of accommodation | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.25 |

| Retaliation | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.17 |

| Direct threat | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.33 |

| Reassignment | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Interviewing | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Exacerbating a condition | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Timing of disclosure | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.83 |

| Average | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| Inability to accommodate | ||||

| Prolonged absence | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.58 |

| Removing essential job functions | 0.75 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.75 |

| Facility operation | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 0.39 |

| Infringement | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Financial ability | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.67 |

| Persistent refusal | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Workplace redesign | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.56 |

| Average | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.56 |

| Explanation | ||||

| Prolonged absence | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| Removing essential job functions | 0.75 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.31 |

| Facility operation | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 |

| Infringement | 0.75 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Financial ability | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.45 |

| Persistent refusal | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.18 |

| Workplace redesign | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Average | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| Post-training | ||||

| Discrimination | ||||

| Refusal of accommodation | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| Retaliation | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| Direct threat | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Reassignment | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.67 |

| Interviewing | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.42 |

| Exacerbating a condition | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Timing of disclosure | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Average | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.73 |

| Explanation | ||||

| Refusal of accommodation | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| Retaliation | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| Direct threat | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.42 |

| Reassignment | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.42 |

| Interviewing | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.58 |

| Exacerbating a condition | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| Timing of disclosure | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Average | 0.89 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.70 |

| Inability to accommodate | ||||

| Prolonged absence | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.92 |

| Removing essential job functions | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.83 |

| Facility operation | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 |

| Infringement | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Financial ability | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Persistent refusal | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.17 |

| Workplace redesign | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Average | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.76 |

| Explanation | ||||

| Prolonged absence | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| Removing essential job functions | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Facility operation | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.67 |

| Infringement | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Financial ability | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Persistent refusal | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 |

| Workplace redesign | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Average | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.76 |

| Participant | Christa | Nate | Justin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Style of teaching | Very well | Very well | Very well |

| Number of sessions | Liked number of sessions | Liked number of sessions | Liked number of sessions |

| Length of sessions | Liked length of sessions | Liked length of sessions | Liked length of sessions |

| Timing of sessions | Liked timing of sessions | Wish we had met a little more often | Liked timing of sessions |

| Knowledge of ADA | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Knowledge of discrimination | 4/5 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Knowledge of inability to accommodate | 4/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schena, D., II; Rosales, R. Autistic Adult Knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Employment-Related Rights. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 748. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070748

Schena D II, Rosales R. Autistic Adult Knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Employment-Related Rights. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(7):748. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070748

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchena, David, II, and Rocio Rosales. 2023. "Autistic Adult Knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Employment-Related Rights" Education Sciences 13, no. 7: 748. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070748

APA StyleSchena, D., II, & Rosales, R. (2023). Autistic Adult Knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Employment-Related Rights. Education Sciences, 13(7), 748. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070748