Abstract

This study examined how recent Doctor of Physical Therapy graduates from a health professions graduate school with an interprofessional curriculum conceptualize their professional and interprofessional identity (i.e., dual identity). Theoretical frameworks included social identity theory, intercontact group theory, and the interprofessional socialization framework. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 12 graduates in their first 1–2 years of practice in inpatient settings. Transcripts were analyzed using iterative and inductive phenomenological analysis to identify themes. Four themes related to professional identity emerged: from patient to physical therapist, profession exceeding expectations, connection with patient, and role affirmation through meaningful work. Six themes related to interprofessional identity emerged: valuing different mindsets, the authenticity of interprofessional education, feeling misunderstood, perceived versus true hierarchy, differing team dynamics, and being on the same page. Approaches to interprofessional education that focus on longitudinal socialization from professional education through clinical practice might best support the development of clinicians who value interprofessional collaborative practice.

1. Introduction

An older, diverse society with increasingly complex healthcare needs calls for integrating various healthcare services [1,2,3]. To optimize healthcare system performance, Berwick et al. [4] developed the Triple Aim focused on enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and reducing costs, which was later expanded to the Quadruple Aim, including caregiver wellness [5]. Central to realizing the Triple Aim was an increased focus on interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP) and associated interprofessional education (IPE) [6]. Despite the benefits of ICP in achieving the Triple Aim, adapting healthcare delivery and health professions education toward ICP and IPE has been slow [6]. Emerging evidence suggests a positive impact on future interprofessional collaboration with early introduction to IPE; however, there continues to be a gap in understanding of best practices in IPE [7].

Healthcare systems globally face worker shortages, resulting in fragmented and expensive care [1,6]. Historically, one reason for the high cost of care was the hierarchical method of healthcare delivery, where payments to physicians for procedures rather than preventive services were incentivized [8]. Patient care is historically delivered in silos of uniprofessional care by each practitioner (e.g., doctor, nurse, occupational therapist) rather than in teams. The transformation of the hierarchical uniprofessional model to ICP is a complex process involving changes in current healthcare providers’ professional and interprofessional identities.

Health professions educators need to design curricula focused on developing both professional and interprofessional identities among future healthcare professionals. Understanding the development of professional identity and its impact on interprofessional identity is key to forming effective interprofessional teams. Unfortunately, health professions education was and continues to be siloed and dedicated to developing strong clinicians in their chosen profession [9]. A shift to socializing students to become collaborative interprofessional team members is a significant challenge globally [1,10,11,12,13]. Focusing on a uniprofessional identity can affect healthcare providers’ collaboration where groups are socialized to favor one group over another (i.e., out-group discrimination) [3,9,14,15]. When health professions education is focused solely on the skills of the chosen profession, students do not have the opportunity to understand others’ roles and responsibilities. Early opportunities to work with students in interprofessional groups that extend into clinical practice are needed to gain insight into how to work as a team to solve complex patient health problems.

Interprofessional identity is an emerging concept in the literature; however, to advance ICP and IPE, it needs to become a more developed concept. Interprofessional identity is drawn from social identity theory (SIT) and intergroup contact theory (ICT), which encompass an individual’s socialization to the attitudes, behaviors, and knowledge about interprofessional collaboration [16]. Little is known about the development of interprofessional identity and the effects of IPE on its development or its influence on professional identity in health professions graduate students [17,18]. Therefore, the purpose of this phenomenological study is to understand professional and interprofessional identity formation in recent Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) graduates who engaged in both uniprofessional and interprofessional curricula. Knowledge generated from this study will inform health professions educators and healthcare delivery administrators on curricular design in health professions education and professional development post licensure to ensure readiness and continued development in interprofessional collaborative care.

Theoretical Frameworks

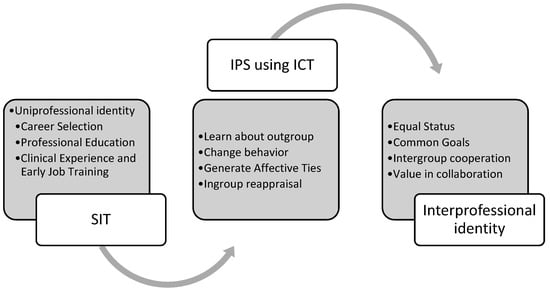

SIT, ICT, and the interprofessional socialization framework (IPS) underpin this study [14,15,16,19,20,21]. The IPS framework provides context and validation for the study, while SIT gives context for understanding professional identity and, therefore, its role in developing interprofessional identity. SIT and ICT provide context to understanding oneself in the larger context of group identification and interaction. To create a more collaborative healthcare environment, healthcare educators must understand how health professionals identify within their profession and as healthcare providers on a team. Figure 1 is a conceptual model demonstrating the interplay of SIT, ICT, and Pettigrew’s process for intergroup attitude change to describe the process of professional and interprofessional identity formation [15,21].

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Uniprofessional and Interprofessional Identity Formation. Note: The conceptual model connects social identity theory (SIT) [19,20], interprofessional socialization framework (IPS) [16], and intergroup contact theory (ICT) [14,15,21].

To break down professional barriers and create behavioral change toward collaboration, an improved understanding of ICT and the right ingredients for positive intergroup contact should be applied to IPE. A recent meta-analysis of intergroup contact theory found that positive intergroup contact typically reduces intergroup prejudice and that contact theory can be applied beyond ethnic and racial groups [15,21]. Pettigrew and Tropp [21] suggest four conditions for effective intergroup relationships: learning about the out-group, changing behavior, generating affective ties, and in-group reappraisal. Applying ICT and Pettigrew and Tropp’s [21] four processes of change through intergroup contact to IPE could improve relationships between healthcare professionals.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Context

Phenomenology is an approach to qualitative research that describes the common meaning of a lived experience for a group of individuals [22]. Phenomenological research attempts to interpret people’s relationship to the world and make meaning out of the lived experiences of these individuals. The process of analysis in phenomenology is iterative, employing a double hermeneutic. It is a qualitative approach trying to understand a first-person account from a third-person position [22]. The principal investigator is a physical therapist who worked in inpatient settings and is a health professions educator who teaches in physical therapy and interprofessional education. Phenomenology recognizes that the researcher cannot fully bracket themselves from the research and acknowledges that the researcher’s experience is part of the participant making sense of the phenomenon [22,23]. As an evolving construct in the literature, this allows a researcher experienced in interprofessional education and collaborative practice to make meaning of the meaning-making of the participants, which will lead to a more robust understanding of the construct. This phenomenological study was approved by the institutional review board MGB Human Research Committee Institutional Review Board and the Northeastern University Humans Research Committee Institutional Review Board. The study context was one graduate school in the Northeast region of the United States with a combined DPT and interprofessional curriculum. Students simultaneously engage in uniprofessional curricula (e.g., genetic counseling, occupational therapy, physical therapy (PT), physician assistant studies, communicant science disorders, and nursing) and an interprofessional curriculum, Interprofessional Model for Patient and Client-Centered Teams (IMPACT), which involves engaging in required and elective interprofessional learning activities and clinical experiences. During the required interprofessional curriculum, students are assigned to small interprofessional teams of five to six students from six different professional programs. The students engage in online didactic content, reflections on a common reading, onsite team-building activities, and simulations with standardized patients. During simulations in the second semester, medical students join the teams. Throughout the first year, students also participate in two interprofessional clinical education experiences on an Interprofessional Dedicated Education Unit at a local hospital. Also, many have interprofessional practice opportunities in the on-campus IMPACT Practice Center, a center dedicated to pro bono care and clinical education.

2.2. Participants

Twelve graduates from an entry level post-baccalaureate graduate DPT program from the classes 2020 and 2021 were recruited via purposive sampling. This initial study focused on DPT graduates only, because they experienced the same uniprofessional and interprofessional education, and this first study could inform a qualitative study of a larger interprofessional group based on identified themes. Only licensed practicing graduates in their final clinical internship experience or first year of practice working in inpatient settings (i.e., acute care hospitals, long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities, and long-term care facilities) were recruited, as it was theorized that the ICP would be more explicit in inpatient settings. Recruitment emails were sent no more than 3 times by the program manager of the program to reduce the potential for coercion.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The interview protocol was structured based on SIT and ICT theory and the IPS framework, and adapted from Brazg’s [24] interview protocol (see Appendix A). Specifically, interviews focused on career selection and professional training, including clinical experiences and early job experiences, and participant perceptions as PTs working on teams early in their careers. Twelve semi-structured interviews were completed. Interviews were approximately 45–60 min long, conducted via Zoom due to COVID-19 social distancing restrictions. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. Field notes were captured during and immediately following interviews, focusing on observations about the interaction with the participant. Interview data were checked for accuracy, then sent to the participants for member checking.

In line with iterative and inductive phenomenology analysis, transcripts were read and reread, bracketing interesting points, identifying compelling quotes, and developing codes to start the initial process of coding and theme development [22,25]. Following hand coding, data were uploaded to NVivo (Version 10) software for further organization of coding and identification of themes by looking across participants’ passages [26]. Based on identified themes, the interpretation of findings was developed considering theoretical underpinning and co-construction of meaning from data analysis.

The principal investigator discussed common codes and emerging themes with two researchers (LB and KN). This manuscript is a portion of the first author’s dissertation. KN and LB were advisors for the dissertation, and KN is the second author. All researchers involved have doctoral training and experience in qualitative research. After final coding, the principal investigator re-read transcripts to check the validity of the draft themes and discussed them with the same two researchers to ensure trustworthiness.

3. Results

Participants in the study were an average of 27.6 years of age, 69% were White, 16% Asian, and 15% Hispanic, practicing in various inpatient settings (see Table 1). They had an average of 3.3 months of practice beyond passing their national PT examination.

Table 1.

Demographics of Participants.

3.1. Conceptualization of Professional Identity

Four themes relevant to professional identity formation in recent graduates emerged: (1) from patient to physical therapist, (2) profession exceeding expectations, (3) connection with patients, and (4) role affirmation through meaningful work. The first theme to emerge from thematic analysis dealt with career selection. Starting with career selection either in high school or college, participants began to identify with the behavior, knowledge, and skills of physical therapists they interacted with as patients or observers in the clinical setting. Many participants described choosing PT due to their own experiences as a patient or a family member’s experience attending physical therapy. Some participants described investigating other medical rehabilitation careers, such as speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, or audiology. However, ultimately participants described being attracted to PT based on their personal experiences, a connection to movement, or a desire for more flexibility than they felt a career in medicine afforded. However, while the PT outpatient setting (often located in a gymnasium) seemed like an appealing place to work, many participants also gained insight into how PT can take place in many settings. Participants observed that PT could be more than just a fun workplace but also life-changing.

3.1.1. Theme: From Patient to Physical Therapist

Participants described first experiencing PT as a patient or a patient’s family member. They reported connecting to the profession due to the focus on movement, the relaxed environment where PT occurred, and the time and connection with the patient. Participants also reflected on how their physical therapists created welcoming environments and built trust with patients. Here, a participant recalls building a rapport with her physical therapist after multiple injuries and the trust she felt for her physical therapist:

Between 2013 and 2017, I think I had five knee surgeries. I tore my ACL three times, twice on the right, once on the left. So, I ended up with a physical therapist, he was a resident at [name of college] and I thoroughly enjoyed working with him. He…developed that patient-to-therapist rapport, and when I tore my ACL the second time, I just called him up and he said, “Come right in”. So, it was very warm, welcoming, and I felt like I was actually making progress.(Participant 11)

3.1.2. Theme: Connection with Patients

As the participants decided on their career selection, they had to complete observation hours as part of the application process to a DPT program. As an observer, these experiences further contributed to solidifying their choice of pursuing a degree in physical therapy. Instead of focusing on their injury and rehabilitation, they focused on how the physical therapist interacted and built rapport with their patients. One participant remarked, “I thought it was really fascinating, and [physical therapists] just had a unique relationship with their patients that I didn’t see with any other healthcare professions”. (Participant 12) This ability to build a relationship and watch a patient’s progress confirmed PT as the participants’ career choice.

One of the reasons identified as a facilitator to building rapport with patients was the time physical therapists spent with their patients, typically between 30 min to an hour. For several participants, time spent with patients was a predominant deciding factor in choosing PT, as described by this participant:

I think the biggest thing for me was seeing the relationship that physical therapists have with the patients, and the amount of time they have with them. I was looking into med school for a while to be a pediatrician, but I think the actual input that we have into the day-to-day over patients as well as seeing them for a long period of time and having an impact on what that outcome might look like, it’s really inspiring to me.(Participant 12)

Participants identified that physical therapists might also have a longer episode of care with the patients. Some clinicians may only see a patient once a year or a few times a year, whereas a physical therapist, depending on the setting, could work with a patient daily or a few times a week over weeks to months.

Several new clinicians spoke of their commitment to sports and movement and passion for understanding the human body. Although they had an interest in movement and the human body, most participants described the ability to get to know the patient as the driving force in becoming a physical therapist.

I realized I liked the whole body picture as far as rehab goes, so instead of just focusing on solely the ear or solely on speech and swallow, I liked the bigger picture of helping people functionally,— because I did also consider med school for a semester, but I realized I really did enjoy getting to know people and developing rapport and I felt like I could do that better as a therapist than as a doctor, so that’s kind of how I ended up in physical therapy.(Participant 11)

While participants had varying degrees of exposure to PT either as a patient or through observation, these were only glimpses into a complex profession. Participants later realized that they understood little about how physical therapists make decisions and how to help patients achieve their goals. They also had little sense of the scope of the profession and the many professional avenues that physical therapists could take.

3.1.3. Theme: Profession Exceeding Expectations

After starting the physical therapist professional program, participants’ understanding of PT expanded as they became aware of how much broader the scope of PT was compared to their own patient experiences and observation hours. Perhaps because many participants had sought PT due to sports injuries, there was the assumption that PT was limited to a focus on sports medicine. Here, a participant talks about that misconception and describes their beginning understanding of the complexity of the thought process involved in making clinical decisions:

All I knew obviously was sports med physical therapy just from personal experience of being a patient, but of course, you don’t really see the side of physical therapy that they’re [physical therapist] thinking and clinical reasoning and clinical judgment and all that [sic]. I had no idea. There were some things that I looked back on that I realized my physical therapist did and, oh, that’s what he was looking for if I had a complication, or I remember I had some pain in the back of my knee and he was doing a lumbar strain and I had no idea what he was doing, so it was cool to connect the dots with what I experienced.(Participant 12)

As a patient and observer, participants were exposed to the more glamorous side of PT. They observed patient interaction but not the indirect aspects of patient care, such as documentation, billing, having difficult conversations, and patient advocacy, for example. Also, many had only been in outpatient or sports clinics. Hence, a DPT program opened many participants’ eyes to the possibilities and experiences of physical therapists outside of the outpatient setting and sports world. Once their understanding of the profession expanded, many participants shifted gears from outpatient aspirations to working with individuals in inpatient settings:

I had an [Integrated Clinical Experience] my first year, and getting to see that inpatient side that I had never experienced before school, I felt very drawn to it, and so I started talking more with people who worked in that setting so I had an idea of what I was getting into before I dove into it, and I felt my path was getting pushed in that direction.(Participant 6)

Beyond clinical practice, participants realized different opportunities in education, research, and belonging to a profession through involvement in the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). Once they realized the scope of PT and chose an area that they wanted to focus on at the beginning of their career, participants reflected on some of the challenges of PT (e.g., constraints of the healthcare system), feeling that they wanted to do more. Some described the weightiness of being someone who is helping people at their most vulnerable times and how they are dealing with more emotions than they had anticipated. However, ultimately, these perceived challenges were outweighed by the feeling that they were doing something meaningful in their work.

3.1.4. Theme: Role Affirmation through Meaningful Work

Although the participants recognized some job challenges overall, they felt that their experience as a physical therapist had solidified their career choice. Even though it is not easy, this participant acknowledges that being able to connect with and motivate a patient to improve their health creates meaning in their work.

That’s what I like about physical therapy. I get to help people take ownership of themselves, their well-being, their livelihood. I don’t do it for them. I can’t just inject you with the medication or give you a medication that does it for you. You have to do it for yourself, so that adds complexity and challenge to the job, but I find it also really rewarding when it happens.(Participant 1)

Participants recognized the gravity and responsibility of working with individuals at difficult times in their lives and how being part of their recovery provided them with joy in their profession. Although participants spoke of some of the challenges of PT, such as systems-level constraints, most affirmed their choice to be physical therapists.

I’d have to say just the feeling of helping someone when they’re in such a vulnerable state and being able to provide them with support they need when they’re recovering from illness and often times pretty severe illness at this stage in their recovery. I think being able to be one of the people they go to for support, whether it’s with functional mobility specifically or just in general recovery process, I think that’s probably the thing I like the most about being a physical therapist, being able to be there.(Participant 3)

Most participants were in their first year of physical therapist practice, still figuring out their role within their practice settings. Factors that had initially attracted them to PT through their early experiences as patients or family members of patients to some extent was still their experience. However, their professional education expanded their understanding of the breadth and depth of the profession. Participants found their greatest joy in connecting and interacting with the patients and seeing them progress toward their goals. In these inpatient settings, they were part of a larger team caring for the patient. This team dynamic was not always as apparent in the outpatient settings where they had initially been exposed to PT. As they developed in these early months as physical therapists, they were beginning to gain confidence in their professional roles and responsibilities and their ability to communicate that to others on the team. Professional identity requires a strong sense of belonging to the profession of choice, and the participants were clearly describing a belonging and pride in being a physical therapist (Table 2).

Table 2.

Themes and Codes for Professional Identity.

3.2. Participant Conceptualization of Interprofessional Identities and Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Professional and Interprofessional Identity Formation

Theme: Valuing Different Mindsets. All participants completed a required three-course interprofessional curriculum and several required and elective interprofessional learning activities that contributed to their interprofessional socialization. Interprofessional student teams participated in team-building exercises, online didactic and discussion work, and simulations of clinical scenarios with standardized patients. Participants reflected on their early interprofessional socialization during graduate school and identified some value in being exposed to students from other professions in terms of understanding roles and improving communication:

I think it helped get a basis for what other professions do in each setting, too. I think I felt pretty prepared going into all my clinicals knowing what [occupational therapy] and speech [and language therapy] were, whereas I feel like there have been other students that I’ve gotten to know on clinicals that are like, what does this person do? Why are you involved in this case more so than I was? So, I feel like it helped me get an understanding of everyone’s involvement in care.(Participant 8)

Participants felt those within the DPT program were like-minded regarding their learning interests. When working with other health professions students, participants were able to appreciate different mindsets and approaches to health problems. Through the IMPACT curriculum, participants were exposed to students in other programs and a diversity of approaches to patient care. Students from a local medical school joined the participants for two of the simulations. Several participants appreciated the value of simulation interactions with medical students, as it brought to light the differences in approaches to communication and teamwork in medical education.

3.2.1. Theme: Authenticity

Several participants described valuing the IMPACT curriculum, and many described the curriculum as foundational for understanding roles and responsibilities and interprofessional communication and teamwork. Participants felt that interprofessional practice looked different from how it was taught. They felt that the classroom experiences were not quite authentic. The standardized patients, who are actors, may have been overly dramatic, or the scenarios and number of team members involved were inconsistent with clinical practice. Here, a participant describes the value of interprofessional simulation but recognizes the difference from real clinical care:

I’ve never really had that type of simulation play out in real life, but it allowed us to interact in a way and collaborate in a way that prepares you for the collaboration you have to do as an interprofessional team member. Even though it doesn’t look exactly like that, I think it was a proper [way of] getting the wheels turning kind of thing, especially for someone who had zero interaction like that prior.(Participant 4)

Although IMPACT may have provided participants with the basics of interprofessional communication and teamwork, participants felt that most of their skill development occurred through clinical education experiences and job experience.

3.2.2. Theme: Feeling Misunderstood and Role Ambiguity

Participants felt that healthcare team members had some understanding of PT, which varied based on the practice setting. Physical therapists were perceived as valued team members to assess the safety and get patients moving again. However, participants were not confident that all team members truly understood the breadth and depth of their knowledge. When asked if others understood the role of PT, participants felt more disconnected from those outside rehabilitation:

I think OTs [occupational therapists] would have a really good perception, just because they work so closely in the setting I’m in. Same with speech therapists. I think between speech, PT, and OT, they’re very much on the same page.… With others like nursing or even PCAs [Personal Care Attendants] and CNAs [Certified Nursing Assistants] and MDs [Medical Doctors], it kind of depends on how long they’ve worked there. I’ve seen a huge difference with MDs who rotate- the pulmonologists rotate- there are some other specialties that rotate-so they’re coming from [name of clinic] or they’re at [ name of clinic] once a month every other month or something like that, so I think sometimes it gets a little lost in translation of what we do.(Participant 11)

Participants noted that just as they had a superficial understanding of the complex thought process that went into PT decision-making when they were patients or observers, participants understood why PT might appear “straight-forward” to other health professionals:

Overall, I think that [for] physical therapy it’s hard for a lot of people to see the benefit that we create, I think, in the long term. And also, we’re not entirely well understood because obviously we don’t only walk our patients, but it’s hard if I’m a nurse on a unit and the only time I see a physical therapist is walking a patient, of course I’m going to put two and two together that this is what the person does, so I think it’s a matter of not fully understanding what we do and also not recognizing our value.(Participant 1)

Due to the priority given to safe discharge from inpatient settings as recovery progresses, there is more perceived overlap between the rehabilitation professional roles. Many skills that the rehabilitation professional trains for are complementary, and individuals require functioning in multiple systems to participate in their life roles. Although the nuance may be clearer to rehabilitation professionals, others with less training and experience in these fields may not perceive the distinct expertise in each profession.

I think for family members or patients; they’re not quite sure the different things we do because, you know, we do everything functionally, so OT is getting them dressed, out of bed, and maybe walking to the bathroom with the goal of getting dressed and using the bathroom, but then I’m getting them dressed, out of bed, and walking to the bathroom for the goals of you need to be dressed and you need to use the bathroom and then we need to walk. It’s hard in their minds to maybe sometimes differentiate. I will say that what I’ve noticed is OT and PT will overlap a lot here. It kind of has to happen for you both to get your goals done.(Participant 10)

3.2.3. Theme: Perceived Versus True Hierarchy

Participants described teamwork in their practice settings as collaborative and respectful, although several participants described some perceptions of hierarchy. This was more likely to occur in a setting where some team members were not always in proximity to each other (e.g., same hospital floor) and, therefore, more difficult to reach. With these team members, who have less interaction with the team on a day-to-day basis, there were feelings of a lack of respect for the scope of PT. At those times, communication may seem more prescriptive than collaborative. Even within the same professional role, there are differences in personalities and preferences that can be challenging to navigate and affect feelings of belonging and place on the team. A participant reflects:

I’ve had to figure out the attendings and the residents and their roles and how they like to be approached and [how] they like to kind of respond: they like to have an open discussion, they like an email, they like a page. I think that’s kind of hard, and there’s definitely still a little bit of the feeling of a hierarchy or seniority in the hospital, which I think is a shame because we’re all on the same team. We honestly see the patients more often than they do, so sometimes that’s been frustrating when you’re trying to get a good relationship with your attending and not having them kind of respect and reciprocate that role.(Participant 10)

Participants acknowledged that the hierarchy could be perceived rather than actual. Participants reflected that, as they gain confidence and skill, they are focused on improving their interprofessional communication. Several participants described being respected in their interprofessional teams but reflected on how they wanted to continue to develop in their ICP. Many participants expressed a desire to develop their own confidence in communicating with the team. When describing ethical dilemmas encountered in their practice settings, many noted changes in a patient’s status and wished that they had spoken up sooner but could not, due to limited confidence in their advocacy skills. When asked to envision their future practice, many commented on gaining confidence in advocacy.

I think in general [my] practice would change to be more confident in the ability to just communicate more with other people, especially speaking out when they might say something to a family that you don’t really agree with and you say hold on, let’s back track here and take a different look at this big picture instead of silently taking it and then talking to the OT partner.(Participant 11)

Others described feeling less confident in their ability to advocate concisely and clearly and noted this as an area of growth. Here, a participant discusses challenges with being decisive:

And I think with a little bit more experience, I could probably be a little bit more concise and decisive in my conversation with the rest of the team, and I think that would help get at least my point across, as well as them understanding what I’m seeing. I think one of the things that I’ve noticed is I’m definitely still on the more passive side because of my lack of experience thus far and feeling like these people have been in this field for however long, much longer than me, they probably know better, even if their discipline has nothing really to do with mobility.(Participant 3)

Another participant reflects that, although the professional role may contribute to status on a team, experience also impacts the hierarchical perceptions. This further supports that the hierarchy may be more related to being a newer clinician who is gaining confidence on the team versus a particular professional role being perceived as higher status on the hierarchal ladder.

I think the role has something to do with it, but at the same time, how people perceive the person fulfilling that role. …taking my CI as an example again—I think everyone understands she’s a really good clinician, she’s seen a lot of stuff—so if she brings something up, there is probably a valuable reason why, especially going between disciplines if that makes sense. Whereas sometimes I think the more “novice” clinicians, young clinicians, not as experienced clinicians, …your role can be a little bit more defined and rigid, and you have to fit into that a little bit more.(Participant 6)

Despite the perceived hierarchical structure, there is still a collegiality to working in the inpatient setting where everyone has the same goal. Some of the perceived hierarchy may be related to the historical hierarchy in healthcare even though behavior does not reflect that power and hierarchy.

Even when the MDs come in and I’m with a patient, they always ask, hey, is it okay if we come in.… They’ll knock [on the door] if it’s okay or if they need to come back, they will come back if I ask them to, so even though there is that technical hierarchy, I don’t feel like anyone asserts anything over each other.(Participant 4)

Some participants described not being fully understood or heard on occasion, especially by individuals whom they did not work as closely with on a day-to-day basis or who were outside the rehabilitation professions. Participants acknowledged that the lack of understanding of PT could be partly due to limited exposure to the physical therapist practice. Other participants expressed that when they felt respected and on the same level as the rest of the team, there was more enjoyment in team collaboration: “The teams that I’ve seen, …I have enjoyed working in more, have been the teams who are a more level playing field with everyone as opposed to a hierarchy” (Participant 6). Interestingly, despite the mention of hierarchy from many participants, participants spoke highly of the collaboration that occurs on the teams. Many participants described being valued and feeling heard and respected despite being early in their careers.

3.2.4. Theme: Differing Team Dynamics

Team dynamics seemed affected by how accessible team members were to each other. The participants who worked in settings where all team members were on the floor sharing space, such as IRFs and acute care, that allowed for frequent face-to-face communication seemed to feel most valued and understood. In other settings where there was more separation of rehabilitation and medical professionals, such as skilled nursing facilities and long-term care facilities, there were more perceived difficulties with teamwork and communication. In acute care, often the nurses, physician assistants, rehabilitation professionals, and case managers were on the same floor, but surgeons were less accessible due to operating room time and other responsibilities, which affected the ability to get answers quickly in some cases. Generally, participants described close relationships and collaborative practices with other rehabilitation team members. There are many possibilities for how these relationships developed, such as the perception that their professions have equal status on the hierarchical ladder. Also, in some hospitals, the rehabilitation professionals share office space and/or treatment areas, which results in significant face-to-face interaction.

In the IRFs and acute care settings, most often, the treating therapist would attend team meetings. However, in some settings, such as LTAC and SNFs, one rehabilitation manager would meet with other disciplines’ managers and administrators for the facility. In these settings, participants described more disconnect with the decision-making process. Despite feeling connected with the other rehabilitation professionals, participants felt less heard by those outside of rehabilitation and administration who were making overall policies at their places of practice. They felt that they had less connection to the decision-making and that their concerns may go unheard:

I love working with my coworkers on the rehab team. We…all have good rapport, we all really enjoy each other’s company, and we all really respect each other, but once you’re outside of the rehab team, once you start getting into the medical team and the administrative team, things kind of break down a little bit. Unfortunately, our communication structure at my workplace is not the best. Among the entire rehab team, we only have one person who goes to meetings as our representative and it’s like a really bad game of telephone where I tell them, they tell them, they tell them, and then maybe we try to do something about it, but it’s a moot point by that point.(Participant 1)

Although proximity enhanced interprofessional communication, the importance of communication in interprofessional practice was not lost on these new clinicians. Several participants commented on the significance of communication, describing it as “critical” or “the way to show a team that you’re supporting them”:

I think especially in the inpatient setting that I’m in, it is crucial that we talk as a team and not just once a week during our big team meetings, but every day and every hour of every day. I talk to my other therapy team members, so speech and OT, after every single session. And then speak to the nurses and doctors and all that a little less frequently, but just as often. I don’t think there’s a single person I don’t talk to at least once during the day.(Participant 8)

3.2.5. Theme: Being on the Same Page

Communication happened in a variety of ways in various settings. Participants described reading other team members’ notes, communicating via a whiteboard in patient rooms, emailing, paging, texting on the hospital phone system, weekly or daily team rounds, and face-to-face interactions: “I provide PT-specific interventions, but it’s really about what the rehab team collectively is doing, so it feels like when we’re working with a patient, we’re all operating as a team to improve their quality of life”.

Many participants described the importance of presenting a united front and understanding each other’s perspectives when communicating with the family. Several participants described challenges when the team had a communication breakdown and provided caregivers with incongruent messages and how that could lead to distrust and affect satisfaction with the care. Participants felt that consistent team communication led to caregivers feeling confident in the teams’ decision-making and that their loved ones were receiving the best care:

And then I think another one is just making sure that everyone has kind of a united front for the family in terms of communication with the family and the patient. I think sometimes problems we run into are the family hears one thing from one person, another thing from another person, and the therapist comes in and says a third thing, and they’re going, “What’s happening?” and then trying to regain the family’s confidence and trust and belief in what you’re telling them can be pretty difficult, so I think having that unified message in front of the patient, in front of the family, everyone being on the same page is really key.(Participant 6)

Although the participants acknowledged that being on the same page in terms of communication with caregivers was important, they did recognize that they did not always agree behind the scenes. Participants described the importance of being able to listen and respectfully disagree. Participants also described the importance of prioritizing and picking their battles by reflecting on whether they needed to advocate for a patient or if there was a different way to problem-solve a solution based on the situation. Often, the team worked together to resolve differences. Having various people gather information can help to get the bigger picture for others on the team. Participants described that being able to work as a team creates value for their role (Table 3).

Table 3.

Themes and Codes for Interprofessional Identity Formation.

4. Discussion

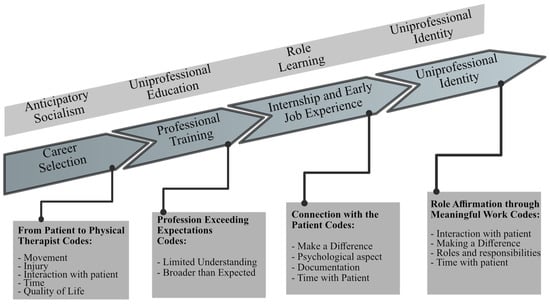

Consistent with the interprofessional socialization framework [16], participants in this study went through a process of professional socialization starting with career selection to physical therapy education and early job experience ending in demonstrating an identity as a physical therapist. Professional identity formation is thought to begin forming in adolescents before entering career-specific education and through connections to a person’s values and background [27,28]. Development of this identity starts when individuals think about a future career and is shaped by societal representations that often contain myths or stereotypes about the selected career [29,30]. For many participants, their first exposure to PT was as a patient, later developing into an interest in pursuing PT as a career due to their positive interactions with their physical therapists and exposure to the clinical environment. These participants, early in practice, demonstrated a beginning identity where they better understood the roles and responsibilities of physical therapy. Many described understanding a much broader scope of responsibility than they conceived of coming into their physical therapist education, such as that of advocate, team member, and motivator. When they entered a DPT program, most assumed they would work with athletes because that was their personal experience. However, during their time as DPT students, they began to appreciate the breadth of opportunities available to them as physical therapists in a variety of practice settings.

Figure 2 is an adaptation of the IPS framework developed by Khalili et al. [16] to illustrate the temporal sequence from career selection to professional training to early job experience to uniprofessional identity in the context of the themes and codes identified through thematic analysis in this study. Relevant professional socialization time points identified were career selection, professional training, and early job experience, which is congruent with the IPS framework [16,31]. Khalili et al. [16] identified media and societal influence on career selection, whereas this analysis identified participants’ personal experiences with PT as a driver of career selection. Professional training and early job experiences were critical in expanding participants’ understanding and perceptions of the physical therapy profession.

Figure 2.

Themes and Codes for Professional Identity Formation in the Context of Interprofessional Socialization Framework. Note. Adapted, with permission, from“An Interprofessional Socialization Framework for Developing an Interprofessional Identity Among Health Professions Students”, by H. Khalili, C. Orchard, H. K. Laschinger, and R. Farah, 2013, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), p. 450 pp. 448–453. (https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.804042) [16]. Copyright 2013 by Hossein Khalili.

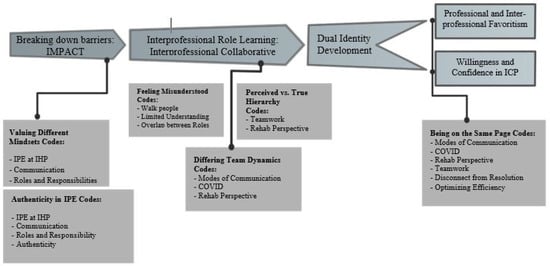

The IPS recommends early IPE in conjunction with uniprofessional education to break down barriers and provide opportunities for interprofessional role learning [16]. Figure 3 displays a modification of the interprofessional socialization framework within the context of the studied institution’s interprofessional curriculum (IMPACT Practice). Khalili et al. [16] describe an interprofessional socialization process. First, the focus is on breaking down barriers between groups and reducing stereotypes to create more equal status during professional education. Then, interprofessional role collaboration leads to a sense of belonging on the interprofessional team. Finally, individuals create a climate for equity of professional perspectives and develop a dual identity [16]. Through engagement in both uniprofessional and interprofessional curricula, participants described an increasing professional identity as a physical therapist. Participants described a better understanding of the roles and responsibilities between professions through their interprofessional curriculum, clinical education, and early job experiences (Figure 3). Participants certainly valued interprofessional teamwork and communication but may not have fully actualized an interprofessional identity in this early stage of their careers.

Figure 3.

Themes and Codes for Interprofessional Identity Formation in the Context of Interprofessional Socialization Framework. Note. ICP = interprofessional collaborative practice; IPE = interprofessional education; IHP = Institute of Health Professions. Adapted, with permission, from “An Interprofessional Socialization Framework for Developing an Interprofessional Identity Among Health Professions Students”, by H. Khalili, C. Orchard, H. K. Laschinger, and R. Farah, 2013, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), p. 451 pp. 448–453. (https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.804042) [16]. Copyright 2013 by Hossein Khalili.

The participants felt that their IPE prepared them to some degree to better understand the roles and responsibilities of various members of the healthcare team. They also found their interprofessional curriculum to be particularly helpful in understanding different communication styles. They acknowledged, however, that the role-learning experience often felt somewhat inauthentic and not quite what they had experienced in their clinical practice. The IPS framework culminates in a dual identity (uniprofessional and interprofessional) [16]. Even with IPE breaking down barriers, participants described a perceived organizational hierarchy in healthcare. Some of the hierarchy may be perceived from existing stereotypes in healthcare or due to decreased confidence of new clinicians. The feelings of hierarchy seemed to vary based on the clinical setting and the accessibility of team members on the floor. More frequent team member interactions seemed to reduce those feelings.

Also, participants understood that for those not trained in rehabilitation science, role distinction might be difficult when focusing on the goal of increasing function to get someone to the next level of care. PT often focuses more on the gross motor tasks that allow individuals to function in their homes. The focus of PT may be on transfers between surfaces, walking, stairs, and balance. In contrast, occupational therapists may focus on activities of daily living such as toileting, dressing, bathing, meal preparation, and eating. Speech-language pathologists are more focused on speech, swallowing, and cognition. Since all of these skills overlap to allow an individual to function in their home and participate in society, the ability to formulate clear role distinctions might be challenging to those outside the professions, especially as the patient progresses toward discharge.

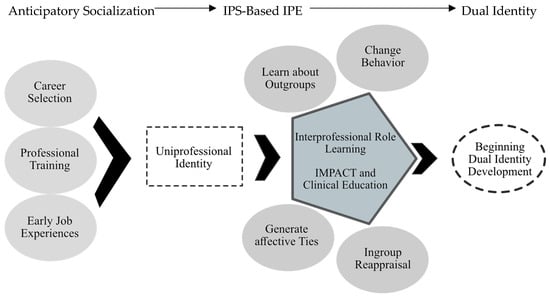

Despite the continued barriers in healthcare systems to ICP, such as lack of access to team members in some settings and limited understanding of the roles and responsibilities of those who do not work as closely on a day-to-day basis, participants described an openness to ICP, fostered early in their education and reinforced through their clinical and early job experiences. Although the participants may not have fully realized a dual identity yet in their early clinical practice, this was facilitated in their professional education and training. It was further solidified through positive team interactions that should foster the ongoing development of a dual identity as a physical therapist and interprofessional team member. It did appear that participants had not completely embraced their identity as interprofessional team members due to some of these challenges, but also due to their own confidence in their clinical reasoning and ability to communicate with the team to advocate for their patients concisely. There were aspects of their practice they wanted to develop further, which is consistent with studies on identity formation in novice physical therapists (Figure 4) [32,33,34].

Figure 4.

Dual Identity Formation in Context of Interprofessional Socialization Framework and Interprofessional Curriculum. Note. IPS = interprofessional socialization framework; IPE = interprofessional education. Adapted with permission from “An Interprofessional Socialization Framework for Developing an Interprofessional Identity Among Health Professions Students”, by H. Khalili, C. Orchard, H. K. Laschinger, and R. Farah, 2013, Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), p. 451 pp. 448–453. (https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.804042) [16]. Copyright 2013 by Hossein Khalili.

Barriers and facilitators to interprofessional socialization in this study provide considerations for IPE and ICP. First, participants identified a lack of authenticity in their IPE that could be addressed in didactic curricula and through the expansion of interprofessional clinical education. Second, although there has been an expansion in pre-licensure IPE, there is less focus in the post-licensure phase, which may be important for continued interprofessional identity formation that facilitates ICP. Although most participants acknowledged the value of gaining insight into other professions’ roles and responsibilities and practicing interprofessional communication in the simulations through their interprofessional curriculum, they felt that ICP looked much different in practice than what they experienced in the curriculum and simulations.

Although logistically challenging, focusing time on interprofessional learning experiences that align closely with the realities of clinical practice may provide better contextual learning. One of the required experiences in the IPE curriculum included a rotation to the Interprofessional Dedicated Education Unit at a local hospital [35,36], which involved direct observation of a health practitioner, not from the student’s discipline, while working on an acute care hospital floor. For example, a nurse may have an occupational therapy and DPT student observe them; then, the students are grouped for debriefing to understand interprofessional practice better. Giving students the opportunity to observe and participate in effective collaborative practice across the continuum of care provides authentic and relatable experiences for students entering early clinical practice.

The IPDEU creates a strategic partnership to facilitate mutual interests [35,36]. The expansion of the IPDEU to various settings provides not only valuable learning experiences for pre-licensure students but also provides post-licensure clinicians the opportunity to engage in IPE and increase learning around interprofessional competencies. Finding opportunities for continued learning in interprofessional groups for clinicians post-licensure will be important to advance the value, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in the clinical environment. Although IPE in pre-licensure education has been gaining traction and demonstrating effectiveness in changing the attitudes of health professions students about teamwork, there is less evidence about interprofessional continuing education post-licensure [37,38,39,40]. One of the early limitations to IPE pre-licensure were logistical barriers posed by rigorous uniprofessional accreditation standards, time, and faculty development needs. Logistical barriers can be even greater in the post-professional world of continuing education [40]. Figure 4 provides a conceptual model of this process in the context of the interprofessional curriculum IMPACT Practice.

Participants in this study, although graduates from a school with a robust dedicated interprofessional curriculum, still described challenges applying what they learned to their early clinical practice as they gained confidence in their own professional roles. In the first year of practice, communication and interaction skills are still developing, and clinicians are learning from others [33,34]. In contrast, in the second year of practice, clinicians engage in more collaborative learning with others and begin to teach other colleagues [33]. The clinical environment is an important area of learning in the first 2 years of practice, and dedicated workshops, learning activities, and mentoring related to interprofessional socialization are important to continue to foster teamwork after licensure. Workplaces that foster an effective learning environment can help to develop lifelong learning opportunities that are interprofessional in nature [9,16].

Participants valued IPE in graduate school; however, they had not had further team-based training since starting clinical practice to reinforce learning of interprofessional competencies. Logistical barriers such as scheduling have long been cited as a barrier to IPE and ICP [40]. Better partnerships between health professions education and healthcare delivery systems that leverage technology could help to break down barriers to post-licensure IPE and create opportunities for learning at all levels of health professionals to ensure competent teamwork [40]. Simulation has long been recognized as a mechanism for advancing IPE [41,42,43]. Simulation provides a realistic approach to a standardized experience that promotes teamwork and allows for a lower-stakes environment to make mistakes without risking patient harm [44,45]. Investment in simulation-based educational technologies in partnership with healthcare delivery systems and health professions education could result in meaningful and more authentic learning experiences pre- and post-licensure. These learning experiences could happen onsite or in a fully virtual environment, reducing logistical barriers and allowing individuals from multiple professions to problem-solve together.

Technology has broken down barriers between healthcare providers and healthcare students and has provided increased access for patients [46]. Participants in this study spoke about team members who were not in the hospital due to safety measures “Zooming” into team conferences. Participants also described the use of a virtual monthly interprofessional evaluation and team conference to allow professionals from different healthcare disciplines to engage in problem-solving for individuals with complex needs. Leveraging these technologies can reduce some logistical barriers to IPE and ICP and allow for learning pre- and post-licensure.

Several participants in this study identified the value of having students from a local medical school join the school’s interprofessional simulations. Participants wished there were more opportunities for this engagement because they felt the communication styles of the medical students were different than what was taught to rehabilitation professionals. Participants in this study also identified stronger collaboration and ease of collaboration with other rehabilitation professionals (e.g., occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists) compared to medical professionals (e.g., doctors, physician assistants, and nurses). Health professions educators should continue to develop interprofessional learning opportunities that closely align with clinical practice, such as interprofessional clinical education. Also, ensuring opportunities to learn with medical, rehabilitation, and social care workers most closely aligns with clinical practice and would provide more authenticity to IPE for health professions students. With the proliferation of new technological innovations in health professions education, new opportunities may exist for health professions schools to partner with medical schools and other programs to break down barriers and advance interprofessional role learning both pre- and post-licensure.

5. Limitations

Participants in this study received a unique interprofessional curriculum in addition to uniprofessional curricula. Because of the dedicated interprofessional curriculum that all students in this context are engaged in during their health professions education, the results of this study may not be transferable to other health professions educational settings. Additionally, this study focused on a group of clinicians practicing in only inpatient settings where access to team members and the concept of teamwork may have been more explicit. Therefore, the study findings may not be transferable to physical therapists working in community-based practices like outpatient practices and home care settings.

Also, almost all participants were from the class of 2021 and very early in their clinical practice. Since the first 2 years of clinical practice is considered a critical period of identity formation with differing benchmarks for each year [32], the transferability of the results to individuals in their second year of practice and beyond may be limited. A study investigating the longitudinal development of interprofessional identity formation may help to inform further post-licensure critical periods for professional development in IPE.

This study purposively sampled only physical therapist graduates as a first step to understanding professional and interprofessional (i.e., dual identity) formation and should be repeated with an interprofessional group of health professions graduates. Repeating this study with an interprofessional sample of graduates from medical and health professions programs, such as social work and public health, may improve understanding of similarities and differences in dual identity formation between professions and could further inform IPE best practices.

6. Recommendations for Future Research

Future research should focus on better understanding dual identity in students and clinicians at different stages: novice through expert. Does professional and interprofessional identity continue as a dual identity, or is interprofessional identity the predominant one in expert practice? Are there critical time periods for identity formation in students and clinicians? What is the correct dosage of IPE to facilitate interprofessional socialization in the student years and clinical practice? Identity formation is iterative, so a better understanding of the longitudinal examination of an interprofessional group of health professions students from graduation through clinical practice could inform appropriate time points and content for pre- and post-licensure IPE. Also, multisite studies at institutions with differing andragogies and dosages of IPE could help inform best practices in program development and the time needed for IPE. Creative partnerships between health delivery systems and health professions education around interprofessional clinical education and post-professional continuing professional development should be investigated.

7. Conclusions

This study investigated how recent DPT graduates in their first year of practice conceptualize their professional and interprofessional identity and identified barriers and facilitators of ICP. Relevant time points for professional identity formation were career selection, professional training, and early job experience. The professional identity formation of participants in this study paralleled the process identified in the interprofessional socialization framework described by Khalili et al. [16].

IPE during graduate school helped to facilitate participants’ understanding of the different roles and responsibilities of the health professions and different mindsets regarding individuals pursuing various health professions careers. Through IPE experiences, they developed attitudes and beliefs regarding the importance of ICP that were further solidified in practice. Participants felt that these learning experiences were not fully authentic to their ICP experiences in clinical practice, highlighting the need for pre-licensure IPE that connects to clinical practice and continued IPE post-licensure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P. and K.N.; methodology, L.P. and K.N.; software, L.P.; formal analysis, L.P. and K.N.; investigation, L.P.; data curation, L.P. and K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P. and K.N.; writing—review and editing, L.P. and K.N.; project administration, L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval granted from the MGB Human Research Committee Institutional Review Board (Protocol number 2021P000703, approved 5 April 2021) and Northeastern University Humans Research Committee Institutional Review Board) Protocol number CPS21-03-03, approved 9 April 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Lynda Beltz, Kristal Clemons, and Keshrie Naidoo for their support as my dissertation committee advisors (LP). We want to thank Shweta Gore for her masterful editing (LP and KN).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- Can you describe what made you decide to pursue a career in physical therapy?

- Was this a shift from what you pursued as an undergraduate?

- Can you describe what led you to pursue physical therapy over another health profession?

- Did your physical therapy education match or not match your expectations?

- What is your favorite part of your job as a physical therapist?

- What are some of the challenges?

- Does your expectation of physical therapy match your experience?

- How would you describe the dynamics of interprofessional healthcare teams at your workplace?

- How would you describe the relationship between the physical therapist and various members of the healthcare team?

- How do you perceive your role on the interprofessional team?

- How clear are your roles and responsibilities to you?

- How distinct is your role from other members of the care team (especially from other rehabilitation providers)?

- Do you feel that your perspective is valued as a member of the interprofessional team?

- Can you describe how you think others perceive your role?

- Can you describe a time in your work where your team faced an ethical dilemma?

- What happened?

- What brought attention to the problem?

- Who was involved in the resolution?

- What process did the team use to deal with the dilemma?

- How did you deal with conflict?

- What did your involvement in the resolution of the problem look like?

- Imagine it is 5 years from now, and you are being recognized for being an outstanding interprofessional team member.

- What would be the storyline?

- How will your practice have changed? Stayed the same?

- What is the headline for the story?

References

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Carron, T.; Rawlinson, C.; Arditi, C.; Cohidon, C.; Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Gilles, I.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I. An Overview of Reviews on Interprofessional Collaboration in Primary Care: Effectiveness. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinders, J.J.; Krijnen, W.P.; Goldschmidt, A.M.; Van Offenbeek, M.A.G.; Stegenga, B.; Van Der Schans, C.P. Changing Dominance in Mixed Profession Groups: Putting Theory into Practice. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwick, D.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Whittington, J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, B.; Lutfiyya, M.N.; King, J.A.; Chioreso, C. A Scoping Review of Interprofessional Collaborative Practice and Education Using the Lens of the Triple Aim. J. Integr. Care 2014, 28, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.L.; Sim, M.; Little, V.; Almost, J.; Andrews, C.; Davies, H.; Harman, K.; Khalili, H.; Reeves, S.; Sutton, E. Pre-entry perceptions of students entering five health professions: Implications of interprofessional education and practice. J. Integr. Care 2019, 22, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, B. Interprofessional education and collaborative practice: Welcome to the “new” forty-year-old field. Advisor 2015, 3, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Khalili, H.; Price, S.L. From Uniprofessionality to Interprofessionality: Dual vs Dueling Identities in Healthcare. J. Integr. Care 2022, 36, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, H. Toward a Theoretical Framework for Interprofessional Education. J. Integr. Care 2013, 27, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, H.; Gray, R.; Helme, M.; Low, H.; Reeves, S. Interprofessional Education Guidelines; Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. Carven Digital: Yorkshire, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.caipe.org/Resources/Publications/Caipe-Publications/Barr-h-Gray-r-Helme-m-Low-h-Reeves-s-2016-Interprofessional-Education-Guidelines (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. What Is CAIPE? 2021. Available online: https://www.caipe.org/about-Us (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update. 2016. Available online: https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2016-Update.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Allport, G.W.; Clark, K.; Pettigrew, T. The Nature of Prejudice; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F. Intergroup Contact Theory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, H.; Orchard, C.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Farah, R. An Interprofessional Socialization Framework for Developing an Interprofessional Identity among Health Professions Students. J. Integr. Care 2013, 27, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.; Williams, S. Professional Identity in Interprofessional Teams: Findings from a Scoping Review. J. Integr. Care 2019, 33, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, R.; Brewer, M.; Flavell, H.; Roberts, L.D. Professional and Interprofessional Identities: A Scoping Review. J. Integr. Care 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social Identity and Intergroup Relations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Social stereotypes and social groups. In Rediscovering Social Identity; Psychology Press: Sussex, UK, 2010; pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 751–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among the Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method, and Research; Sage Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brazg, T.N. The (Inter)Professional Identity of Hospital Social Workers: Integration and Operationalization of Profession-Specific Knowledge, Skills, and Values with Boundary-Spanning Competencies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (Released in March 2020). 2020. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Gendron, T.; Myers, B.; Pelco, L.; Welleford, E. Promoting the development of professional identity of gerontologists: An academic/experiential learning model. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2013, 34, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R. Fixing identity by denying uniqueness: An analysis of professional identity in medicine. J. Med. Hum. 2002, 23, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Hean, S.; Sturgus, P.; Macleod Clark, J. Investigating the factors influencing professional identity of the first-year health and social care students. Learn. Health Soc. Care 2006, 5, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, M.; Norman, I.; Cooper, S.; Gill, E.; Hilton, R.; Judd, P.; Jones, S.C. Interprofessional perceptions of health care students. J. Integr. Care 2013, 17, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, H.; Orchard, C. The Effects of an IPS-Based IPE Program on Interprofessional Socialization and Dual Identity Development. J. Integr. Care 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.L.; Jensen, G.M.; Mostrom, E.; Perkins, J.; Ritzline, P.D.; Hayward, L.; Blackmer, B. The First Year of Practice: An Investigation of the Professional Learning and Development of Promising Novice Physical Therapists. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 1758–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, L.M.; Black, L.L.; Mostrom, E.; Jensen, G.M.; Ritzline, P.D.; Perkins, J. The First Two Years of Practice: A Longitudinal Perspective on the Learning and Professional Development of Promising Novice Physical Therapists. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.M.; Gwyer, J.; Shepard, K.F.; Hack, L.M. Expert Practice in Physical Therapy. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, G.; Portney, L.G.; Vega-Barachowitz, C.; Jampel, A.; Schnider, M.E.; Inzana, R.; Zeytoonjian, T.; Fitzgerald, P.; Tuck, I.; Jocelyn, M.; et al. The Interprofessional Dedicated Education Unit: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Innovative Model for Fostering Interprofessional Collaborative Practice. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2020, 19, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, P.S.; Tuck, I.; Knab, M.S.; Doherty, R.F.; Portney, L.G.; Johnson, A.F. Competent in Any Context: An Integrated Model of Interprofessional Education. J. Integr. Care 2018, 32, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyess, A.L.; Brown, J.S.; Brown, N.D.; Flautt, K.M.; Barnes, L.J. Impact of Interprofessional Education on Students of the Health Professions: A Systematic Review. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2019, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guraya, S.Y.; Barr, H. The Effectiveness of Interprofessional Education in Healthcare: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safabakhsh, L.; Irajpour, A.; Yamani, N. Designing and Developing a Continuing Interprofessional Education Model. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, G.E. The Future of Health Professions Education: Emerging Trends in the United States. FASEB BioAdv. 2020, 2, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaganas, J.C. Exploring Healthcare Simulation as a Platform for Interprofessional Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA, 2012. Available online: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/91 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Palaganas, J.C.; Epps, C.; Raemer, D.B. A history of simulation-enhanced interprofessional education. J. Integr. Care 2014, 28, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Olson, J.K.; Sadowski, C.; Parker, B.; Alook, A.; Jackman, D.; Cox, C.; MacLennan, S. Interprofessional Simulation Learning with Nursing and Pharmacy Students: A Qualitative Study. Qual. Adv. Nurs. Educ.-Av. Form. Infirm. 2014, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, T.; Phillips, S.; Patel, S.; Ruggiero, K.; Ragucci, K.; Kern, D.; Stuart, G. Virtual Interprofessional Learning. J. Nurs. Educ. 2018, 57, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar, G. Simulation-Enhanced Interprofessional Education in Health Care. Creat. Educ. 2015, 6, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, L.M.; Hoots, B.; Tsang, C.A.; Leroy, Z.; Farris, K.; Jolly, B.; Antall, P.; McCabe, B.; Zelis, C.B.R.; Tong, I.; et al. Trends in the Use of Telehealth During the Emergence of the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, January–March 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).