Abstract

In the context of the efforts to reach equity in the classroom, peer feedback (PFB) is used, among other participative learning methods, as it is considered to minimize gender differences. Yet, recent studies have reported gender discrepancies in students’ willingness to provide feedback to their peers. Building on Gilligan’s theory of moral development, we tried to refine the source of this difference. We conducted a semi-experimental study during which education students of both genders performing a PFB activity in a face-to-face course were asked to fill out a questionnaire. This allowed us to estimate the link between, on the one hand, the comfort in providing PFB and the willingness to provide PFB, and on the other hand, personal characteristics like self-esteem, self-efficacy, and empathic concern, and intellectual characteristics like self-efficacy in the learned discipline and the proficiency to write and understand feedback. The linear regression analysis of 57 students’ answers to the questionnaire did not reveal gender differences in comfort in providing PFB and willingness to do so, but showed that the comfort in providing PFB was linked to cognitive proficiency in students of both genders, whereas the willingness to provide PFB was independent of any other variables in men and linked to self-esteem, empathic concern, and comfort in providing feedback in women. This result indicates a differential sensitivity to social factors in male and female students, aligning with Gilligan’s model of women’s ‘ethics of care’. Possible applications in education would be the use of PFB to train women in self-esteem or, inversely, the improvement of psychological safety in PFB exercises in groups including female students.

1. Introduction

School and academia are not places free of gender issues: gender biases and discrepancies, internalized prejudice, and fear of prejudice are still encountered there. Though the gap between female and male students diminishes regarding skills and achievements (in many fields, women, on average, even outperform men (See [1]), women are still less comfortable in situations involving social components like “enrolling, attending, fully participating… in school” [2]. Indeed, several learning settings in widespread use have proved to be unfavorable for female students. For instance, in lessons consisting of whole-class discussions, male college students are reported to participate more than females [3,4]. But conversely, other learning settings seem to favor female students. For instance, in collaborative learning, all-girls groups compared with all-boys groups demonstrate more collaboration and a less argumentative quality [5]. The proportion of females in a learning group improves the group’s emotional management [6]; and finally, improves the group’s performance [7]. Based on these considerations, progressive pedagogical practices try to balance the diversity of learning settings in order to ensure a fair learning experience for each student and at the same time to educate the students on egalitarian behaviors that they can apply to real-life settings. For these two purposes, the stream called ‘feminist pedagogy’ calls for favoring non-dominative learning configurations that respect and make room for individual differences, such as collaborative learning or participatory assessment [8]. Yet, not every participative learning strategy implies genders equity. Specifically, providing peer feedback is sometimes experienced quite differently by male and female students [9,10,11,12,13].

1.1. The Possible Gender Discrepancies in Peer Feedback

Peer feedback (PFB) is a formative assessment method in which students formulate a reaction about the performance or the learning product of fellow students in order to help them improve it [14]. This method is known to improve both the assessor’s and the assessee’s learning, to help students grasp assessment processes [15], and to develop students’ high order thinking skills [16,17] and critical thinking [18], their ability to cope with critique [14], and their self-esteem [19,20]. In most cases, it enhances students’ motivation to learn and their self-efficacy (for a review, see [21]).

Today, PFB is becoming more popular through its use in online courses with wide attendance [22] that have equal opportunity as one of their goals. Yet, it is not always accepted by students [23] and a negative attitude towards PFB also impairs the benefits it can bring [24,25]. The involvement of social interactions in peer feedback influences its outcomes in complex ways [12,21,26,27]: for instance, discomfort due to the fear of hurting a peer may diminish the motivation to participate in PFB [28], and peer pressure often impairs the reliability of the feedback [26,29]. Thus, this learning method suffers from both a gender bias and gender differences: the content of PFB is sometimes guided by the receiver’s gender (gender bias) [30,31], and students’ willingness and ways to provide PFB seems to be gender-dependent (gender difference). In what concerns gender differences in the attitudes towards PFB, the literature displays non-consistent results. Some authors do not report any gender difference in students’ attitude towards PFB in group work [32,33] or online settings [30,34,35,36]. Others [9,10] report that female students (in all cases pre-service teachers) were less willing to provide PFB than male students, or less comfortable to do so [10,37]. Finally, one article [1] described more positive attitudes towards PFB in female students. At the same time, from the point of view of PFB quality, some researchers estimate that women’s feedback on academic tasks was more profound and personal than men’s [38,39,40], but others report that mixed gender assessor-assessed dyads conducted a more polite but less profound interaction during feedback [41]. This unclear picture of students’ attitude towards PFB should be elucidated in order to help male and female students to cope with, take advantage of, and overcome gender differences in their attitude toward PFB [42,43]. This is the general goal of the research that we introduce in the present report.

1.2. Psycho-Social Models of Gender Differences

As a factor predicting differences in feelings and beliefs, gender is expected to influence in multiple ways the reactions of students to the requirement of providing PFB. In this paper, we use the term “gender” to distinguish between men and women, as it is customary when the topics that are considered are social issues and not biological characteristics [44]. At the same time, we categorized male and female participants in this research according to their declared sex. In doing so, we are conscious that we might miss some of the nuances of gender issues. The first nuance concerns specific people who do not identify according to their assigned binary biological sex or do not agree to identify in a binary mode. The second nuance concerns all the people, and it pertains to the definition of gender as a continuum: indeed, independently of biological sex, different people may behave in a more masculine or in a more feminine way, and this impacts many of their personal characteristics. Therefore, when gender is measured as a continuum (with a questionnaire such as the Bem Sex-Role Inventory [45]), some of the personal characteristics that are only weakly correlated with sex appear to be strongly correlated with gender as it is measured. This is what was found, for instance, in studies linking the degree of femininity or masculinity of the participants’ self-concept with their empathic concern (e.g., [46]) or with their self-esteem (e.g., [47]). Yet, in most populations today, the social treatment conferred to people is based on their biological sex, and therefore it is also important to characterize people as belonging to the two clearly defined groups: men and women. In the following part, we consider two theoretical models which were developed in order to rationalize the differences between men and women.

The first model of gender differences is the basic feminist theory [48,49] that states that the different socialization of men and women leads women to feel that, compared with men, they have some inferiority (internalized oppression), or to fear that they will be supposed to have some inferiority (fear of prejudice) in certain fields [2]. In the general national population, this global inferiority feeling is translated into several personal characteristics. One of them is the trait self-esteem, which is defined as the extent to which a person prizes, approves, likes, or values him or herself [50] and has been consistently observed as lower in women [51,52]. Another personal characteristic is self-efficacy, that is, the evaluation of one’s proficiency and chances of succeeding at a specific task or in learning a specific discipline [53]. Women’s lower self-efficacy in some activities like mathematics has even been observed when women had the same objective achievements [54]. These differences in self-esteem and self-efficacy persist from childhood to college years [55]. An additional difference that can be explained by gender-specific acculturation is women’s lesser willingness to stand out than men [56]. Yet, among teachers, most studies report no gender difference in self-esteem, even in very culturally diverse societies (e.g., [57,58]).

The second model of gender differences pertains to characteristics that do not assume inferiority. Departing from the point of view of simple power relationships, several theoreticians claimed that a fundamental difference between men and women lies in the way they take others into account. In particular, Gilligan’s theory of moral development [59] proposes that, on average, moral reasoning in men is based more on principles like justice or individual rights, whereas moral reasoning in women is based more on social connectedness and on responsibility for people’s needs (‘an ethics of care’). Gilligan’s theory is not an essentialist view of gender differences [60], since it considers men’s and women’s tendencies in moral judgement as socially constructed to various extents and as possibly fluid, but it describes an actual difference between men and women that has successfully explained various behaviors. This model explains, for instance, the greater propensity of women to choose professions focusing on caring for people [61]. In terms of personal characteristics, this model allows one to account for the observed relative superiority of women in emotional abilities [62], including emotional intelligence [19] and dispositional empathic concern [63,64]. It also yields a greater conformity to the group among women [65]. Yet, as the case of self-esteem, gender differences in empathic concern among teachers are less pronounced than in the general population [66].

1.3. A Model of Gender-Sensitive Factors Influencing Attitudes towards PFB

The two theories reported here allow us to form hypotheses about the way gender may influence students’ feelings when providing PFB, and attitudes about providing PFB. In order to do so, we recall that in general, attitudes (here for instance, the willingness to provide feedback) are shaped by cognitive influences (for instance, the knowledge about one’s proficiency in the learned discipline or in feedback) and affective influences (for instance, fear of hurting someone when providing feedback) [67]. Affective influences may be emotions experienced when performing the activity [34], such as comfort, discomfort [68], and pleasure. They may also be beliefs rooted in cognitive appraisal, like the belief that peers’ assessments are less accurate than the instructor’s assessment, or the belief that it is not fair to assess peers [69]. Emotions and beliefs may not be fully correlated: some people may think it is good to give feedback but feel uncomfortable when doing so [70]. In accordance with this dichotomy between cognitive and affective factors, several typologies of factors influencing attitudes towards peer feedback have been built. For instance, Panadero [71] distinguished between ‘intrapersonal’ feelings (e.g., discomfort), cognitively based feelings (e.g., trust in the self as an assessor), and ‘interpersonal’ feelings (e.g., friendship). In parallel, Zou and colleagues [70] distinguished between ‘interpersonal negative concerns’ (will PFB impair relationships?) and ‘procedural negative concerns’ (is PFB fair?), and we [12] made up a classification based on two dichotomies: concrete (cognitive or practical) vs. affective factors, and personal vs. task-related factors. In the following part, we review those personal factors that influence students’ feelings and attitudes towards PFB, and which are at the same time known to display a recognized gender difference.

The theory of women’s relative sense of inferiority allows one to predict gender differences in students’ attitudes towards PFB, which occur directly or through the mediation of personal traits. First, women’s lower perceived status in society could directly influence their attitude towards PFB. Indeed, doubts about PFB’s fairness is a known problem [69,72,73] that may impair the willingness to participate in the exercise [11,70,74]. In the case of female students, the fear of gender bias can explain part of the stronger fairness concern observed among women in PFB [43]. Second, women’s social position is linked to several factors that could mediate the influence of gender on attitudes towards PFB.

One of these factors is the trait self-esteem. Providing PFB includes standing out, resisting social pressure, demonstrating some superiority to another person [75,76], and even taking the risk of hurting them [77,78]—that is, gaining power over somebody [18,79]. Therefore, it is logical that a lower self-esteem impairs the willingness to provide PFB [10,80]. Conversely, receiving PFB implies being able to stand the critique of peers [11,23,26] and a possible ‘loss of face’ [81]. Therefore, lower self-esteem impairs the ease of receiving critiques [82,83], and this is what has been observed with women in specific settings [84]. Another close phenomenon, the stronger tendency of female students to interpret negative feedback as indicating a lack of ability rather than lack of motivation [85], has also been related to women’s relatively lower self-esteem. Through an identification mechanism, these problems in receiving feedback possibly influence students’ willingness to provide PFB. As a conclusion, one can expect the link between gender and the willingness to provide PFB to be mediated by self-esteem.

The same rationale can be used to predict that the impact of gender on PFB could be mediated by self-efficacy in the subject matter and self-efficacy as an assessor (‘trust in oneself as an assessor’ [86]. Indeed, self-efficacy in the subject matter and self-efficacy as an assessor have been shown to be positively linked to students’ attitudes about PFB [24,86]. Students [18,23], and among them pre-service teachers [87], often question the legitimacy of students’ feedback in comparison to the instructor’s feedback. The lower ‘trust in the self as assessor’ observed in women [88,89] could explain women’s reported lower trust in peer feedback in comparison with the instructor’s feedback [18].

Another factor that can be related to a power difference between men and women is students’ epistemic beliefs: like most non-dominant groups in society, women were found to hold less conservative epistemic beliefs than men: they were less inclined to see science as a collection of truths that cannot be discussed, or scientific writing as representing a universal truth. A conservative view of science has been shown to correlate with a lower confidence in the feedback of peers as compared with instructor feedback, which seems more secure [90], and even with a lower peer feedback quality [91,92]. Therefore, contrary to the other variables, women’s less conservative conception of knowledge [91,92,93] should predict a greater acceptance of PFB and better performance in it [40,94].

The theory of gender-specific ethics also applies to PFB, since providing PFB involves the comparison of the performance of somebody else to a norm, and as such, it is essentially a judgement activity. This theory allows us to predict the existence of gender differences linked to social cohesion issues. Since women appear to be more concerned than men about group cohesion, their assessment should be directly subjected to biases like “friendship marking” and “decibel marking” [95], and the consciousness of this problem should impair their conception of PFB, as observed in mixed populations [86]. Women’s greater focus on interpersonal relationships may also influence their attitude about PFB though personal traits, one of them being dispositional empathic concern, as we have already stated.

Since the specific influence of dispositional empathic concern on the attitude towards PFB has not yet been researched, we can only express hypotheses here. On the one hand, the fact that feedback is a kind of help suggests that higher empathic concern should be linked to a greater willingness to give feedback to a peer, as has been observed in some cases [14]. On the other hand, the consciousness that peer feedback may hurt its recipient is expected to raise negative emotions towards PFB [96]; one of these emotions is, for instance, the feeling that PFB is less fair to other students than the instructor’s assessment [23,97]. Yet, in some cases, even this consciousness has been shown to be positively correlated with participation in PFB [70], and the anxiety to provide feedback was shown to be linked with feedback accuracy [98]. Thus, regarding gender differences, if women display higher empathic concern in comparison to men [63], and therefore have a higher consciousness that PFB may help and also hurt [86], then they should have a greater willingness than men to provide PFB [43] but also feel less comfortable doing so.

In conclusion, the two models of gender differences allow us to hypothesize that two kinds of variables may predict gender differences in PFB: the model of felt inferiority generates hypotheses about ‘intrapersonal’ [71] variables and the model of different ethics generates, rather, hypotheses about ‘interpersonal’ [71] variables. Moreover, the existing knowledge in these fields leads to several predictions concerning the influence of the different variables on comfort and willingness to provide feedback and some of these predictions contradict each other. The purpose of the present work is to help evaluate the relative impact of these influences.

1.4. Research Questions

On the basis of the preceding discussion, the specific goal of the present research was to check the possibility of explaining gender differences in attitudes towards PFB by differences in the trait self-esteem and dispositional empathic concern. Since, as we recalled, an attitude always has an affective basis, we split the students towards PFB into two variables: we defined the comfort in providing PFB [71] (or ease of providing feedback [37,99]) as the degree of positive feelings and beliefs experienced by the student during the activity, and the willingness to provide PFB as the degree of positive attitude towards providing PFB (or positive opinion about PFB’s usefulness [37]. Our general hypothesis was that these two variables could be influenced by personal characteristics like the trait self-esteem [50] and dispositional empathic concern [63], controlling for academic characteristics such as students’ self-efficacy in the learned discipline [100] and students’ proficiency in feedback [21], and that self-esteem and empathic concern could mediate gender differences.

The hypotheses that we intended to verify are listed here with a distinction between cognitive (cog) and social (soc) parameters:

- Compared with men, women should display lower self-esteem and lower self-efficacy in the learned discipline, but higher empathic concern (H1);

- The comfort in providing PFB should increase with students’ self-esteem or self-efficacy in the studied discipline as well as their proficiency in providing PFB (H2cog), but decrease with empathic concern (H2soc);

- The willingness to provide PFB should increase with students’ self-esteem or self-efficacy in the studied discipline as well as their proficiency in providing PFB (H3cog), and increase with empathic concern (H3soc);

- Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and empathic concern should mediate the link between gender and attitudes towards PFB (H4)—compared with men, women should display a lower comfort in providing PFB and a lower willingness to provide PFB.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The research was conducted according to a semi-experimental design. It involved a convenience sample including 57 pre-service teachers studying in a small teacher training college. The students were aged from 18 to 37 years, 19 were men and 38 were women. The sex imbalance in the sample reflects the situation of the teaching sector. The students were in different years of study, and already had a succinct teaching experience that included giving feedback to pupils. Most students (43) were physical education teachers, and the others were science pre-service teachers. The students performed a PFB activity in one of four different F2F courses where one of the final requirements was to prepare and give a whole-class presentation as a team, and to give public feedback to another team of students who taught another topic. In the two physical education courses, the students had to present to the class an actual sports activity, and in the two science courses, they had to perform a computer-supported presentation on a topic enlarging the knowledge acquired in the course (see [101]). After each presentation, the other students in the class were required to give oral feedback. There was no special training in feedback giving. This open FTF feedback, as opposed to online feedback, fit the goal of the research, since it maximized the human interactions for which we wanted to account. Face to face feedback is also thought to yield specific gains to the feedback activity [71]. We did not record which gender pairing occurred during the actual PFB activity between providers and recipients of feedback and assumed that men and women gave feedback to men and women in a random way. On the day when the students completed these two requirements, they were presented with an informed consent form and a questionnaire. The study received the approval of the Authors’ College’s Ethics Research Policy, and was conducted in accordance with its principles.

2.2. Research Tools

The self-reported questionnaire included the following Likert scales (all of them except self-efficacy, from 1 = “I do not agree at all” to 5 = “I very much agree”). For each index, the reported Crohnbach alpha values were computed on our sample. Alpha values obtained were close to the ones published in the literature, except for IRI.

Self-esteem was evaluated using a 5-point Rosenberg’s scale [46] including positive and negative items and used as a continuum (alpha 0.859).

Self-efficacy in the studied discipline was evaluated using the 8 corresponding items of MSLQ’s 7-point Likert scale according to Pintrich and colleagues [100] (alpha 0.936).

Empathic concern was evaluated using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), a 5-point Likert scale [66] including 7 items (alpha 0.601).

The proficiency in feedback was evaluated by two items: ‘I find it hard to find what to write in my feedback’ and ‘It is hard for me to express what I want to say in my feedback’ (alpha 0.660).

Comfort in providing PFB (alpha 0.792) and willingness to provide PFB (alpha 0.765) were assessed on 5-point Likert scales using the following items inspired by Cheng & Warren [102], Authors [12], and Vanderhoven and colleagues [99], and covering most categories defined by Panadero [71]: our variable “comfort” related to Panadero’s [71] intrapersonal (emotion, fairness and comfort, and interpersonal factors (friendship, psychological safety)), and our variable “willingness” related to some of his cognitive factors (trust in the self as assessor, trust in the other as assessor), and one intrapersonal factor (fairness).

2.2.1. Comfort in Providing Feedback (* Indicates Inverse Coding)

- I feel uncomfortable providing peer feedback *;

- It is difficult for me to formulate feedback to a peer;

- When I provide feedback to a peer, I fear hurting him or her *;

- Feedback containing negative remarks can hurt *;

- If I provide critical feedback, this can hurt me afterwards *;

- When I provide feedback, I do not think it can hurt;

- I loved providing feedback;

- I have no affective difficulty in providing feedback, I am not shy or careful when providing feedback.

2.2.2. Willingness to Provide Feedback (* Indicates Inverse Coding)

- People manage their learning as they wish, no matter what feedback they will receive from a peer *;

- In my opinion, it is not right to criticize a peer *;

- I think that when I provide feedback to a peer, it helps both of us;

- My feedback will help people learn;

- People are certainly grateful about the help they receive in feedback;

- I do not think that my feedback will be useful to the people who receive it *;

- It is important to give feedback to peers because it helps them learn.

Comfort in receiving (instead of giving) PFB was also measured and found to have a high correlation with comfort in providing PFB, but it did not add an explanatory dimension to our analysis and therefore we did not include the corresponding data in this report.

Gender was asked according to three possibilities: ‘male’, ‘female’ or ‘other’. Only two students chose the third possibility, and since they were the only ones, they were discarded from the sample.

2.3. Data Analysis

Questionnaire validation was made on an independent sample and led to slight modifications in the original questionnaires up to the form published here. Before using the data of the sample, we checked with appropriate T-tests that there were no significant statistical differences between the different kinds of students (different years of study, different courses, and different mother tongues) involved in the quasi-experiment, according to any of the parameters that were considered in this research. All the following calculations, including linear regression, were made and examined both for the whole group and for each gender separately. A Shapiro–Wilk test was performed on every variable and did not show evidence of non-normality. The distributions of the variables for each gender group were slightly skewed in opposite directions, but as reported in the following part, this did not impair the validity of the linear regression analysis. The possibility of collinearity was checked on the basis of the correlations and every explanatory variable was subjected to regression analysis against relevant others, in order to refine its relationships with them and to detect possible mediation effects. No significant correlation was found between the two main explanatory variables (self-esteem and empathic concern). The correlations between the other variables and self-esteem are accounted for in the analysis.

3. Results

As a first step, the means and standard errors of the studied variables were computed (Table 1), as well as the zero-order correlations between them (Table 2).

Table 1.

Students’ characteristics, comfort in providing PFB, and willingness to provide PFB (means, standard deviations, and t-test comparison between gender groups).

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations between students’ characteristics and attitudes towards PFB (first row is the whole sample and, in parentheses, correlation in men only/women only).

The goal of the analysis that was performed in a second step was to deepen the links between the variables. We addressed the problem of multiple comparison by running a set of linear regression calculations with each of the variables as the dependent variable, in order to estimate the relative influence of the different variables on each other and to pick up the variables that explained a larger part of others’ variance. Moreover, in order to create a directional order between the variables, we made the fundamental hypothesis that, in accordance with the theory of attitudes [67], comfort in providing PFB could influence the willingness to provide PFB, but not the contrary. On this basis, we applied multiple linear regression by first studying the predictive potential of students’ characteristics (proficiency in feedback, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and empathy) on the comfort in providing PFB (Table 3), and then included the comfort in providing PFB as one of the explanatory variables along with the four latter characteristics in the study of the willingness to provide PFB (Table 4). In each case, the homoscedasticity of the distribution was evaluated by assessing the predicted probability plot, and the residuals were found to be rather equally distributed. Mediation analyses were performed when appropriate.

Table 3.

Regression analysis predicting comfort in providing peer feedback.

Table 4.

Regression analysis predicting willingness to provide peer feedback.

In men, on the one hand, 56% of the variance in comfort in providing PFB was predicted by self-efficacy in the discipline and proficiency in feedback (Table 3), and further regression analyses showed that these variables did not mediate any other personal characteristics. Specifically, it appears that higher self-efficacy in the discipline was linked to a lesser comfort in providing feedback. On the other hand, men’s willingness to provide PFB was not significantly predicted by any of the studied variables (Table 4), with the most probable but not significant link being proficiency in feedback.

In women, 40% of the variance in the comfort in providing PFB was significantly explained by the proficiency in feedback (Table 3). Proficiency in feedback entirely mediated the influence of empathic concern on the comfort in providing feedback, as could be shown by a separate regression analysis predicting the proficiency in feedback in women from personal characteristics (R2 = 0.397, F(3, 31) = 10.2, p = 0.000, b = 0.628, p = 0.000 for empathic concern), but proficiency in feedback did not mediate any link with the other personal characteristics self-esteem or self-efficacy. Regarding the willingness to provide PFB, 67.8% of the variance was significantly explained by two orthogonal variables expressing personal traits (Table 4): self-esteem and empathic concern, and by the comfort in providing feedback, which fully mediated the influence of the proficiency in PFB. Self-efficacy in women was strongly correlated with self-esteem but was not directly linked to the willingness to provide feedback (p = 0.142). A regression analysis performed on the whole sample (men and women together) gave results close to those of the women’s group.

4. Discussion

No gender discrepancies in self-esteem, self-efficacy, and empathic concern were found in our sample (H1 was not verified). The absence of gender differences in the trait self-esteem confirms previous results obtained on teachers [57] and may be explained by the feminization of the teaching profession: indeed, female respondents feeling more aligned with their situation are known to score higher on self-esteem tests. Since our sample consisted of physical education and science pre-service teachers, which are disciplines considered as more manly, it is possible that the women in the sample gained special self-esteem from the fact that their field of study already challenged the superiority of men. The nature of the teaching profession can also account for the absence of gender differences in the trait empathy, since teaching requires a mindset from practitioners of both genders that is closer to what is considered as feminine empathic capacities [58].

In what concerns the correlations between personal characteristics, the absence of a link found between self-esteem and empathic concern in both genders was in accordance with previous research [63]. In female students and not in male students, self-efficacy and the trait self-esteem were observed to be very significantly correlated, and this is in accordance with the hypothesis that both characteristics are slightly impaired among women because of the same difference in socialization [54]. In female students only, there was a significant link between the proficiency in feedback on the one hand and empathic concern on the other hand. This suggested that empathic concern is a personal trait that, at least in our sample, women built on when providing peer feedback more than men did.

With respect to gender differences in attitudes towards PFB, our results did not confirm the claims reported in some of the previous research [9,10,11] and match (H4 not confirmed): in our sample, students of both genders displayed, on average, moderate to positive comfort in providing PFB and moderate to positive attitude towards PFB (Table 1.) This modest feeling of comfort is in accordance with previous research, see [21]. Yet, our results unveiled more subtle phenomena that were not described before.

First, and independently of gender considerations, our results suggest that comfort in providing PFB (an emotion) and willingness to provide PFB (an attitude) have some different foundations in students’ minds. In our sample, comfort in providing PFB was mostly linked to cognitive variables: in men, 56% of the variance in the comfort in providing PFB could be explained by self-efficacy in the learned discipline and by proficiency in feedback, and in women, 40% of its variance could be explained mostly by proficiency in feedback (H2cog verified, H2soc invalidated). This result strengthens the finding of other authors about the link between proficiency in feedback and comfort in providing feedback [86]. The negative link found in men between self-efficacy in the discipline and comfort in providing feedback can be explained by the supposition that students with a stronger proficiency in the discipline have more features to critique in their peers’ products, and therefore they have more reasons to fear they may hurt their peers [28,98]. The willingness to provide feedback, on the contrary, was eventually (in women) linked to social traits, self-esteem, empathic concern, and to comfort in providing feedback, but was not directly linked to cognitive characteristics (H3cog invalidated, H3soc confirmed). In the framework of the theory of attitudes, this separation between cognitive and social influences is a common configuration [67]. In practice, this shows an essential difference between comfort in providing PFB and willingness to do so. Indeed, when a student is required to provide PFB, he or she will feel more difficulty in doing this and fear hurting the other more if he or she has a lesser proficiency in doing this, or if he or she is more knowledgeable on the topic and expects to have a lot of critique to deliver, and this shows that students are conscious that in academic settings, intellectual proficiency determines the appropriate impact of PFB on the receivers. Conversely, when a student needs to make the decision to provide PFB or is asked to approve this type of exercise on a fundamental level, his or her reaction is not based on specific cognitive considerations, but eventually involves social and affective components.

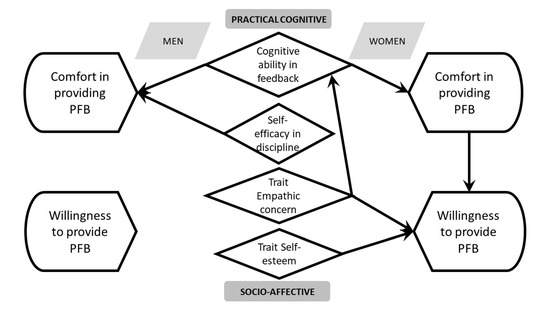

Second, regarding gender differences, our results suggest that although men and women in our sample displayed the same level of comfort in providing PFB and of willingness to provide PFB, the underlying mechanisms leading them to their attitudes were different for each gender (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relationships among the variables in the case of male students (left) and female students (right) according to the statistical analysis of the data.

The original finding of this study was that instead of influencing the willingness to provide PFB through the mediation of personality traits, like we hypothesized (H4), gender seemed to be a factor that moderated the link between socially significant traits and the willingness to provide PFB. Indeed, in our experiment, it appears that men were willing to give feedback anyway, independently of what they knew they were able to say, of their self-esteem, of how they feared to hurt others, and of their willingness to help the other person, and this despite their possessing these characteristics at the same level as women, on average. In contrast, in our sample, for an average female student to be more willing to provide PFB, she had to be self-assured enough to stand out, she had to possess a stronger desire to help the receiver, or for additional reasons, she had to experience less discomfort when providing PFB. The link found for women between the willingness to provide PFB and two alternative socially significant traits, self-esteem and empathic concern, suggests that for women, the principal concern in PFB was not cognitive but social. This hypothesis of the importance of social traits in the willingness to provide feedback is reinforced by the fact that self-efficacy in the learned discipline, which depends partly on cognitive characteristics, as opposed to self-esteem, was not a predictor of the willingness to provide PFB, whereas the more social trait, self-esteem, was. In summary, in our sample, PFB seemed to be considered by women as a socially loaded act, whereas for men, it seems to be…just an act. Our findings fit the logics of Gilligan’s model [59], since according to this model, moral judgement is driven more by social considerations in women, and by formal considerations in men. They also corroborate the finding that in free non-academic settings, male students give more feedback but are less prone to interpret comments as a critique than female students [84]. On a day-to-day casual level, our conclusion can be brought together with the impression given by conversations in adolescent groups: in these situations, boys generally criticize one another without restraint and receive critiques without much discomfort, whereas girls have a much more careful, sophisticated, and lengthy way of providing critiques and reacting to them.

Limitations of the Present Work

From a methodological point of view, on the one hand, several biases are possible in the present research. The drawbacks of self-reporting as a data collection methodology are well-known. The small sample size and its sex imbalance may generate validity issues, and some of the unsignificant correlations found could be attributed to it. Self-reported questionnaires imply the risk of social-desirability bias or of gender bias. Moreover, while the trait self-esteem and dispositional empathic concern are generally stable in students, on the contrary, self-reported self-efficacy [53,100], self-reported proficiency in feedback [21], and the attitude towards PFB [21,36,74] may be influenced by contingent variables. For instance, the PFB exercise which was performed close to filling out the questionnaire could influence the feelings of self-efficacy and the willingness to provide PFB that they declared in the questionnaire [23,102] and influence students’ attitudes towards PFB [11]. On the other hand, the relationships found in this study between personal traits and comfort or willingness to provide feedback seem to be strong enough to compensate for the small sample size. It is worth suggesting that since, in our sample, women and men displayed similar levels of self-esteem and empathic concern, the effects revealed in this study should be even stronger in samples where women and men display these characteristics at different levels. An additional methodological suggestion can be based on the regression analysis that we performed of our whole sample: this analysis yielded results similar to those of the female students alone and occulted the effects that were found for male students. This analysis suggests that the results of other studies on PFB using mixed gender samples without gender differentiation may hide gender effects similar to the one identified here.

From a theoretical point of view, it is clear that the model of influences that we built upon two major paradigms of gender differences has limitations. We could include in this model additional personal characteristics that are known to be moderated by the gender parameter. For instance, in relationship with women’s weaker power in society, women were found to hold less conservative epistemic beliefs, and in relationship to women’s stronger concern with social issues, women, on average, were found to seek more conformity than men. These characteristics and perhaps others could explain additional parts of the variance in the comfort to provide PFB and the willingness to do so.

5. Conclusions

From the point of view of gender studies, our results describe a rather optimistic global picture where male and female students display homogenous behaviors in self-esteem and empathic concern, as well as comfort in providing PFB and willingness to provide PFB. At the same time, these results suggest that similar behaviors in men and women do not automatically mean similar mindsets. Indeed, in our sample, men who displayed more willingness than the others to provide PFB did not have a special profile in terms of self-esteem or of the trait empathic concern; yet women who displayed more willingness than other women to provide PFB had mostly either more self-esteem or more willingness to help other people (empathic concern). This could imply that, in order to behave in the same manner as men in PFB, women had to dig into psychological resources that men did not have to use. Thus, it is possible that women find ways to adapt to men’s behavioral norms in peer feedback, but that they do it without changing their internal tendencies. Such an effect is well-known in women’s studies. Of course, this insight does not allow us to draw conclusions about the innate or socially acquired nature of gender differences in attitudes towards PFB [59], but it shows that a difference between men and women in PFB may exist even if it is not blatant.

5.1. Directions for Future Research

The model that we tried to confirm in this report may help to understand psycho-social influences affecting PFB. First, the reproduction of our research design with larger samples and other populations (students in other disciplines and non-students) could ascertain the validity of this model. Second, attempts to improve this model could be made by envisioning additional parameters that possibly influence students’ attitudes towards PFB. Since the characteristics that were our focus did not explain all the variance in students’ feelings and attitudes towards PFB and willingness to provide PFB, one could search for other factors that could act differently on men and women, such as additional personal traits or cultural factors. The use of qualitative research tools in the study of students involved in PFB could help to approach these additional factors. Third, regarding gender, the use of a questionnaire defining gender as a continuum could help to distinguish between those PFB-relevant behaviors that are linked to the social categorization of people according to their biological sex (for instance, the fear of discrimination), and those behaviors that stem from personal traits linked to gender measured on a continuum (for instance, the fear of standing out), and should therefore be addressed independently from their biological sex. Finally, from an educational point of view, an experimental manipulation of the learning climate or of the learning methods in use is also expected to yield gender differences in comfort and willingness to provide PFB and could be used to devise new teaching methods.

5.2. Educational Development

From a practical point of view, our results show that behavioral homogeneity in a mixed gender group does not negate the need to be aware of deep gender differences in the psychological mechanisms that allow students to shape their behavior. Therefore, our study could inspire some improvements in the use of PFB in learning settings. The format of PFB exercises could be adapted to the motivations of each gender. For instance, in order to enhance women’s motivation to participate in PFB, one could devise conditions enhancing the feeling that PFB is helpful to others, as is the case for feedback in microteaching, for instance, or conditions grouping the learners in groups of friends [103] or groups characterized by a high interdependency and psychological safety. Conversely, the use of PFB with no gender adaptation could help in raising students’ awareness of gender differences, just as the use of non-anonymous peer feedback is valuable in order to foster deep interpersonal cognitive exchanges in learning [104]. Thus, it could help to forge female students’ self-assurance [20] and men’s thoughtfulness. Finally, the gender difference emerging in this research also suggests the need to differentially train teachers to adapt their feedback to the situation they are in, independently of the personal and sometimes gender-biased way of expressing feedback. We think that in some cases, like in feedback to a skilled student on a technical exercise, it is important to bluntly express the truth about the other’s performance, and this suggests the need for some women to behave in a more ‘manly’ way. In other cases, for instance, when teaching low achievers [105], we think that it is important to be careful about the affective and social significance of feedback, and this requires that men, too, behave according to an ‘ethics of care’.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and Y.P.; methodology, R.S., Y.P., D.-E.S. and G.H.; validation, D.-E.S. and N.R.; formal analysis, R.S. and D.-E.S.; investigation, Y.P., R.S., D.-E.S., O.H.B. and E.W.; resources, D.-E.S., O.H.B. and E.W.; data curation, D.-E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-E.S.; writing—review and editing, D.-E.S., Y.P, N.R. and G.H.; visualization, D.-E.S.; supervision, D.-E.S.; project administration, N.R., O.H.B., E.W.; funding acquisition, R.S., Y.P., D.-E.S. and N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a internal grant of the former Ohalo Academic College in 2020 and the redaction of the article was made possible by a retreat of the Unit for Gender Equality at Tel Hai Academic College.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the former Ohalo Academic College (2008 and 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The first author wishes to dedicate this article to the loving memory of Elie Saada (Sadino) Seroussi, University of Paris.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Warrington, M.; Younger, M. The Other Side of the Gender Gap. Gend. Educ. 2000, 12, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, E.K.; Mensch, B.S.; Psaki, S.R.; Haberland, N.A.; Kozak, M.L. PROTOCOL: Policies and interventions to remove gender-related barriers to girls’ school participation and learning in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the evidence. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2019, 15, e1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crombie, G.; Pyke, S.W.; Silverthorn, N.; Jones, A.; Piccinin, S. Students’ perceptions of their classroom participation and instructor as a function of gender and context. J. High. Educ. 2003, 74, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Mccabe, J.M. Who Speaks and Who Listens: Revisiting the Chilly Climate in College Classrooms. Gend. Soc. 2021, 35, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asterhan, S.C.; Schwarz, B.; Gil, J. Small-Group, Computer-Mediated Argumentation in Middle-School Classrooms: The Effects of Gender and Different Types of Online Teacher Guidance. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 82, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunaway, M.M. IS Learning: The Impact of Gender and Team Emotional Intelligence. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2013, 24, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Curşeu, P.L.; Chappin, M.M.H.; Jansen, R.J.G. Gender diversity and motivation in collaborative learning groups: The mediating role of group discussion quality. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, L.; Watkins Allen, M.; Walker, K.L. Feminist pedagogy: Identifying basic principles. Acad. Exch. Q. 2002, 6, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C.; Waring, M. Student teacher assessment feedback preferences: The influence of cognitive styles and gender. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, Y.; Bar-Shalom, O.; Sharon, R. Characterization of Pre-service Teachers’ Attitude to Feedback in a Wiki-environment Framework. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2014, 22, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.L.; Tsai, C.C. University students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward (online) peer assessment. High. Educ. 2006, 51, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seroussi, D.E.; Sharon, R.; Peled, Y.; Yaffe, Y. Reflections on Peer Feedback in Disciplinary Courses as a Tool in Pre-service Teacher Training. Camb. J. Educ. 2019, 49, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammons, J.L.; Brooks, C.M. An Empirical Study of Gender Issues in Assessments using Peer and Self Evaluations. Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 2011, 15, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Topping, K. Peer Assessment: Learning by Judging and Discussing the Work of Other Learners. Interdiscip. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dochy, F.; Segers, M.; Sluijsmans, D. The use of self-, peer-, and co-assessment in higher education: A review. Stud. High. Educ. 1999, 24, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.S.J.; Liu, E.Z.F.; Yuan, S.M. Web-based peer assessment: Feedback for students with various thinking-styles. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2001, 17, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.Z.; Lin, S.S.; Chiu, C.; Yuan, S. Web-based peer review: The learner as both adapter and reviewer. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2001, 44, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.F.; Carless, D. Peer feedback: The learning element of peer assessment. Teach. High. Educ. 2006, 11, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Emotional Intelligence at Work: A professional Guide; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsmeier, B.A.; Henrike, P.; Maja, F.; Schneider, M. Peer feedback improves students’ academic self-concept in higher education. Res. High. Educ. 2020, 61, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E.; Alqassab, M.; Fernández-Ruiz, J.; Ocampo, J.C.G. A systematic review on peer assessment: Intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2023; 1–23, Published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, S.E.M.; Blakemore, L.; Marks, L. Is peer review an appropriate form of assessment in a MOOC? Student participation and performance in formative peer review. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.; Cooper, A.; Lancaster, L. Improving the quality of undergraduate peer assessment: A case for student and staff development. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2002, 39, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gennip, N.A.E.; Segers, M.S.R.; Tillema, H.H. Peer assessment as a collaborative learning activity: The role of interpersonal variables and conceptions. Learn. Instr. 2010, 20, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.R.; Brown, G.T.L. Opportunities and obstacles to consider when using peer- and self-assessment to improve student learning: Case studies into teachers’ implementation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 36, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gennip, N.A.E.; Segers, M.S.R.; Tillema, H.H. Peer assessment for learning from a social perspective: The influence of interpersonal variables and structural features. Educ. Res. Rev. 2009, 4, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Tang, C. Student engagement with peer feedback in L2 writing: A multiple case study of chinese secondary school students. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 2023, 46, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, K.; Mather, R.; Jones, H.; Lusuardi, C. Student Engagement with Peer Assessment: A Review of Pedagogical Design and Technologies. In Advances in Web Based Learning ICWL 2009; Spaniol, M., Li, Q., Klamma, R., Lau, R.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; p. 367e375. [Google Scholar]

- Panadero, E.; Romero, M.; Strijbos, J.-W. The impact of a rubric and friendship on peer assessment: Effects on construct validity, performance, and perceptions of fairness and comfort. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2013, 39, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow, D.D.; Treinen, K.P. The role of gender in perceived speaker competence: An analysis of student critiques. Commun. Educ. 2004, 53, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, T.; Ropers, G. How gendered is the peer-review process? A mixed-design analysis of reviewer feedback. PS Political Sci. Politics 2022, 55, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatfield, T. Examining satisfaction with group projects and peer assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 1999, 24, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listyani, L. Gender-based responses to peer reviews in academic writing. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2019, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.H.; Hou, H.T.; Wu, S.Y. Exploring students’ emotional responses and participation in an online peer assessment activity: A case study. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2014, 22, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collimore, L.M.; Paré, D.E.; Joordens, S. SWDYT: So What Do You Think? Canadian students’ attitudes about peerScholar, an online peer-assessment tool. Learn. Environ. Res. 2015, 18, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Schunn, C.D.; Wang, Y. What makes students contribute more peer feedback? The role of within-course experience with peer feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2021, 47, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praver, M.; Rouault, G.; Eidswick, J. Attitudes and affect toward peer evaluation in EFL reading circles. Reading 2011, 11, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hamer, J.; Purchase, H.; Luxton-Reilly, A.; Denny, P. A comparison of peer and tutor feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, O.; Hatami, J.; Bayat, A.; van Ginkel, S.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Mulder, M. Students’ online argumentative peer feedback, essay writing, and content learning: Does gender matter? Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, O.; Banihashem, S.K.; Taghizadeh Kerman, N.; Parvaneh Akhteh Khaneh, M.; Babayi, M.; Ashrafi, H.; Biemans, H. Gender differences in students’ argumentative essay writing, peer review performance and uptake in online learning environments. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022; 1–15, Published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanjani, A.M.; Li, L. Exploring L2 writers’ collaborative revision interactions and their writing performance. System 2014, 44, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchikov, N. Improving Assessment through Student Involvement: Practical Solutions for Aiding Learning in Higher and Further Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Guijarro, S.; Bengoechea, M. Gender differential in self-assessment: A fact neglected in higher education peer and self-assessment techniques. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, S.; Babor, T.F.; De Castro, P.; Tort, S.; Curno, M. Sex and Gender Equity in Research: Rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2016, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, S.L. The measurement of psychological androgyny. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivtzan, I.; Redman, E.; Gardner, H.E. Gender role and empathy within different orientations of counselling psychology. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2012, 25, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, A.; Rosenberg, J.A. Androgyny, masculinity, and self-esteem. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 1987, 15, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beauvoir, S. The Second Sex; Alfred, A., Ed.; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Jacklin, C.N. The Psychology of Sex Differences; Stanford Unversity Press: Redwood, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, B.; Grabe, S.; Dolan-Pascoe, B.; Twenge, J.; Wells, B.; Maitino, A. Gender differences in domain-specific self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2009, 13, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W.; Arslan, R.C.; Denissen, J.J.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Gebauer, J.E.; Potter, J.; Gosling, S.D. Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A Self-efficacy: Towards a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [CrossRef]

- Zander, L.; Höhne, E.; Harms, S. When Grades Are High but Self-Efficacy Is Low: Unpacking the Confidence Gap Between Girls and Boys in Mathematics. Front. Psychol. Sec. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 11, 552355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorra, M.L. Self-efficacy and self-esteem in third-year pharmacy students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2014, 78, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, K.B.B. Evidence on Self-Stereotyping and the Contribution of Ideas. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 129, 1625–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, E.; Dhingra, K.; Boduszek, D. Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, self-esteem, and job stress as determinants of job satisfaction. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2014, 28, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, N.; Mubashir, T.; Tariq, S.; Masood, S.; Kazmi, F.; Zaman, H.; Zahidb, A. Self-Esteem and Job Satisfaction in Male and Female Teachers in Public and Private Schools. Pak. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 12, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Heyes, C.J. Anti-Essentialism in Practice: Carol Gilligan and Feminist Philosophy. Third Wave Feminisms. Hypatia 1997, 12, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, P.; Ting, Y.Y.; Tan, K.Y. Sex and care: The evolutionary psychological explanations for sex differences in formal care occupations. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Núñez, M.T.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Montañés, J.; Latorre, J.M. Does emotional intelligence depend on gender? The socialization of emotional competencies in men and women and its implications. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 6, 455–474. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christov-Moore, L.; Simpson, E.A.; Coudé, G.; Grigaityte, K.; Iacoboni, M.; Ferrari, P.F. Empathy: Gender effects in brain and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 46, 604–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tašner, V.; Mihelič, M.Ž.; Čeplak, M.M. Gender in the teaching profession: University students’ views of teaching as a career. CEPS J. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2017, 7, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, N.K.L. The impact of stress in self- and peer assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2005, 30, 51e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. Students’ perceptions of fairness in peer assessment: Evidence from a problem-based learning course. Teach. High. Educ. 2013, 18, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Schunn, C.D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F. Student attitudes that predict participation in peer assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E. Is it safe? Social, interpersonal, and human effects of peer assessment: A review and future directions. In Handbook of Social and Human Conditions in Assessment; Brown, G.T.L., Harris, L.R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- McConlongue, T. But is it fair? Developing students’ understanding of grading complex written work through peer assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.-Y. Anonymous versus identified peer assessment via a Facebook-based learning application: Effects on quality of peer feedback, perceived learning, perceived fairness, and attitude toward the system. Comput. Educ. 2018, 116, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijbos, J.-W.; Pat-El, R.; Narciss, S. Structural validity and invariance of the Feedback Perceptions Questionnaire. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 68, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D.; Gallagher, F.M. Coming to terms with failure: Private self-enhancement and public self-effacement. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 28, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Tai, J.H.M. Grudges and gratitude: The social-affective impacts of peer assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topping, K.J. Self and peer assessment in school and university: Reliability, validity and utility. In Optimising New Modes of Assessment: In Search of Qualities and Standards; Segers, M., Dochy, F., Cascallar, E., Eds.; Kluwer Academic: Groningen, 2003; pp. 55–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.; Bol, L. A Comparison of Anonymous Versus Identifiable e-Peer Review on College Student Writing Performance and the Extent of Critical Feedback. J. Interact. Online Learn. 2007, 6, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Thomsen, T.; Scagnetti, G.; McPhee, S.R.; Akenson, A.B.; Hagerman, D. The scholarship of critique and power. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2021, 9, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, M.H.; Brockner, J.; Frankel, B.S. Self-esteem and reactions to failure: The mediating role of overgeneralization. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.; Ng, R. Peer assessment of oral language proficiency. Perspectives 1994, 6, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.D. High self-esteem buffers negative feedback: Once more with feeling. Cogn. Emot. 2010, 24, 1389–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; De Pater, I.E.; Judge, T. Differential affective reactions to negative and positive feedback, and the role of self-esteem. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Sex differences in reactions to evaluative feedback. Sex Roles 1989, 21, 725–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Davidson, W.; Nelson, S.; Enna, B. Sex differences in learned helplessness: II. The contingencies of evaluative feedback in the classroom and III. An experimental analysis. Dev. Psychol. 1978, 14, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotsaert, T.; Panadero, E.; Estrada, E.; Schellens, T. How do students perceive the educational value of peer assessment in relation to its social nature? A survey study in Flanders. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2017, 53, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.L.; Tsai, C.C.; Chang, C.Y. Attitudes towards peer assessment: A comparison of the perspectives of pre-service and in-service teachers. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2006, 43, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, C. Students as evaluators in practicum: Examining peer/self assessment and self-efficacy. In Proceedings of the National Conference of the Association for Counselor Education and Supervision, New Orleans, LA, USA, 27–31 October 1999; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sluijsmans, D. Establishing Learning Effects with Integrated Peer Assessment Tasks; The Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, S.Y.; Cho, Y.H. Predicting Pre-Service Teachers’ Intention of Implementing Peer Assessment for Low-Achieving Students. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, C.J. An Exploratory Study of the Relationship between Epistemological Beliefs and Self-Directed Learning Readiness. Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Noroozi, O. The role of students’ epistemic beliefs for their argumentation performance in higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2022; 501–512, Published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter Magolda, M.B. Knowing and Reasoning in College: Gender-Related Patterns in Students’ Intellectual Development; Jossey Bass: Hoboka, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Banihashem, S.K.; Noroozi, O.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Tassone, V.C. The intersection of epistemic beliefs and gender in argumentation performance. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2023; 1–19, Published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pond, K.; Ul-Haq, R.; Wade, W. Peer Review: A Precursor to Peer Assessment. Innov. Educ. Train. Int. 1995, 32, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, F. Emotions related to identifiable/anonymous peer feedback: A case study with turkish pre-service english teachers. Issues Educ. Res. 2021, 31, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.H.; Schunn, C.D. Students’ Perceptions about Peer Assessment for Writing: Their Origin and Impact on Revision Work. Instr. Sci. 2011, 39, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqassab, M.; Strijbos, J.; Ufer, S. Preservice mathematics teachers’ beliefs about peer feedback, perceptions of their peer feedback message, and emotions as predictors of peer feedback accuracy and comprehension of the learning task. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhoven, E.; Raes, A.; Montrieux, H.; Rotsaert, T.; Schellens, T. What if pupils can assess their peers anonymously? A quasi-experimental study. Comput. Educ. 2015, 81, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R.; Smith, D.; Garcia, T.; McKeachie, W. A Manual for the Use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ); The University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- de Grez, L.; Valcke, M.; Roozen, I. The impact of an innovative instructional intervention on the acquisition of oral\presentation skills in higher education. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 112e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Warren, M. Having second thoughts: Student perceptions before and after a peer assessment exercise. Stud. High. Educ. 1997, 22, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, A.R.; Luque, M.; Letón, E.; Hernández-del-Olmo, F. Automatic assignment of reviewers in an online peer assessment task based on social interactions. Expert Syst. 2019, 36, e12405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotsaert, T.; Panadero, E.; Schellens, T. Anonymity as an instructional scaffold in peer assessment: Its effects on peer feedback quality and evolution in students’ perceptions about peer assessment skills. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 33, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh Kerman, N.; Noroozi, O.; Banihashem, S.K.; Karami, M.; Biemans, H.J.A. Online peer feedback patterns of success and failure in argumentative essay writing. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2022; 1–13, Published online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).