The Gender Gap in STEM Careers: An Inter-Regional and Transgenerational Experimental Study to Identify the Low Presence of Women

Abstract

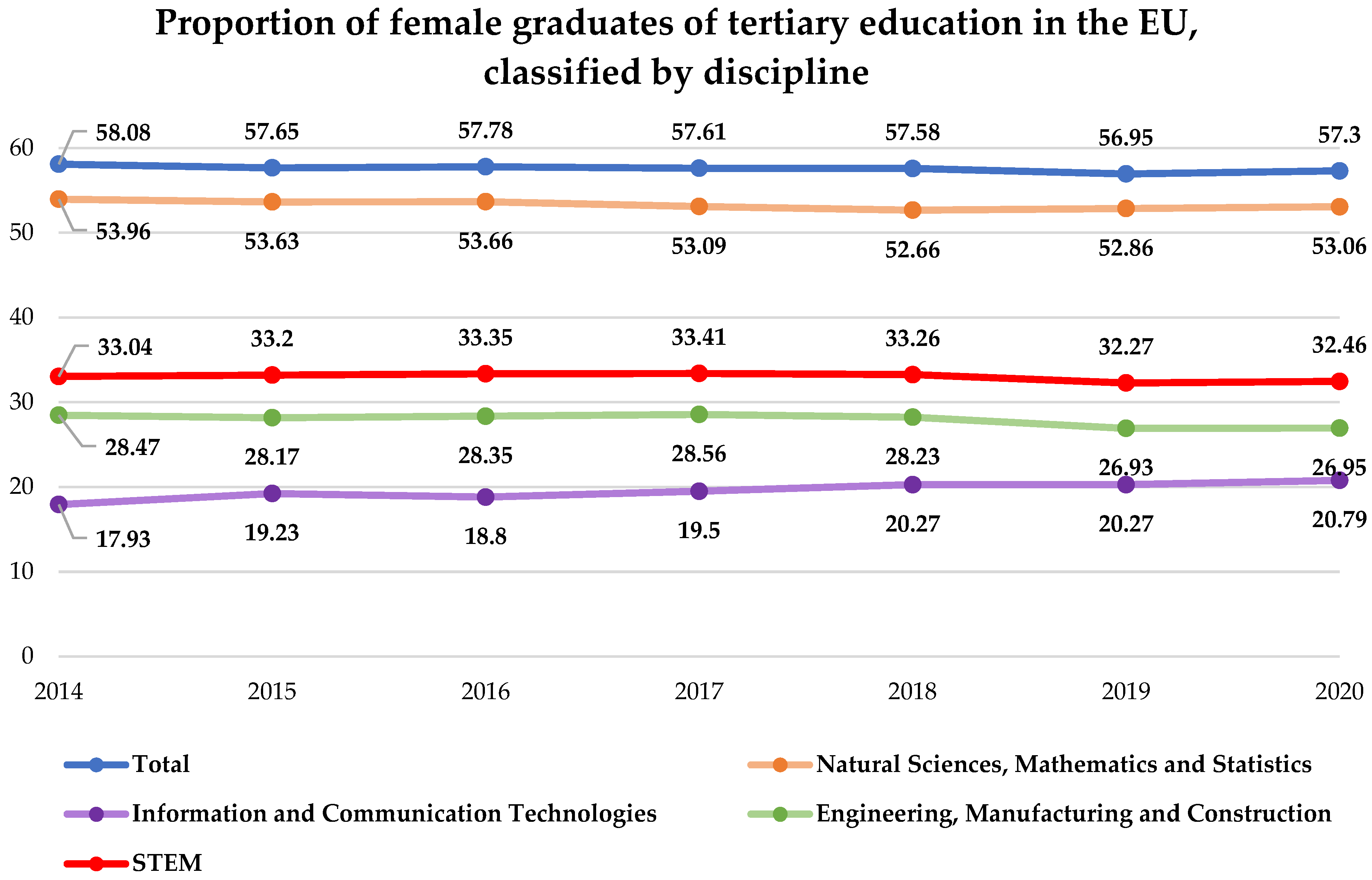

1. Introduction

- There is a graduate shortage due to negative perceptions of STEM professions;

- Major technological advances mean that degrees have to adapt to these changes;

- There is a common perception that most STEM professions are not gender-neutral.

- Interregional and international scope: the study is carried out in different regions of Spain (Huelva, Cadiz, and Badajoz), and in three European countries (Italy, Austria and the Czech Republic).

- Target groups: the sample analysed is made up of young people at five different moments of the life cycle, all linked to the transition to adult life (primary education, secondary education, higher education and the early stages of their entry into the labour market), with the aim of identifying the reasons for the low presence of women in STEM environments.

- Academic year: the study includes the entire education system, from primary education to university education.

- Survey analysis tool: the surveys are based on a multi-model theoretical foundation applying three theories: the expectancy–value theory of motivation, the social role theory and the gender stereotypes theory.

- Activities: participatory workshops led by women specialists in STEM fields. These workshops are given in primary and secondary education settings, and the workshops are adapted to the educational level at which they are given.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ALAS Approach: Foundation and Methodology

2.1.1. Methodology and Surveys

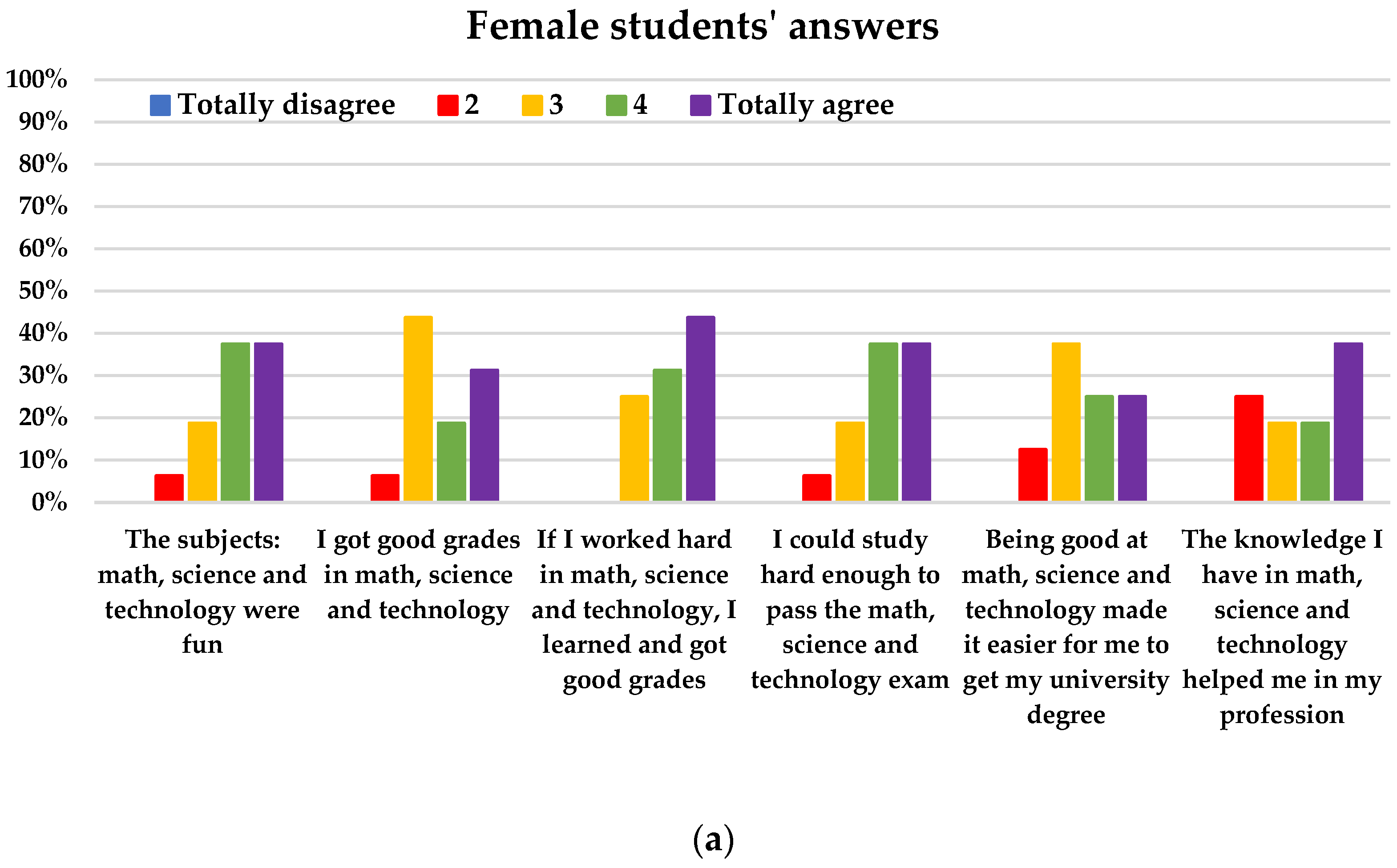

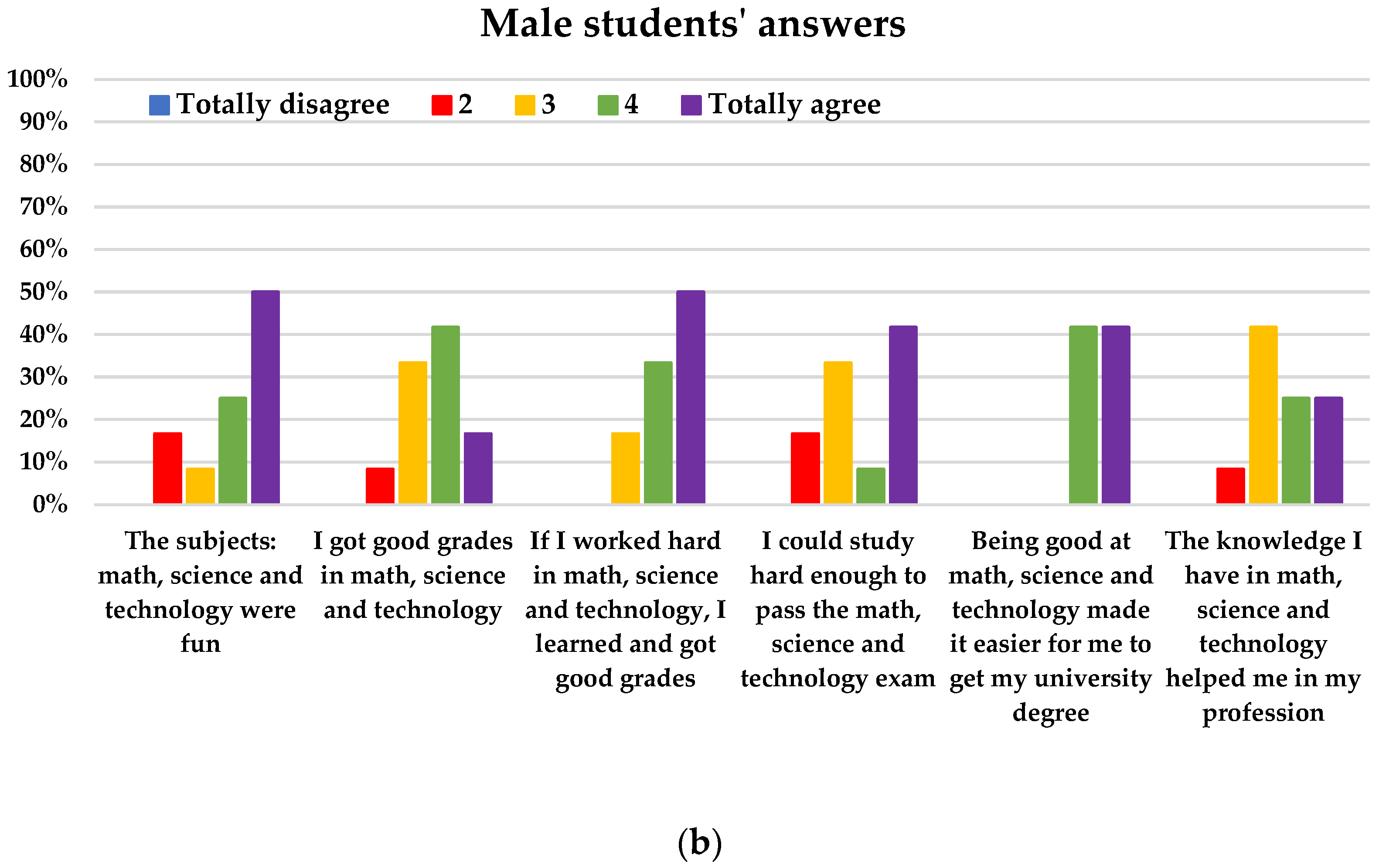

- The expectancy–value theory of motivation [22,23,24,25,26]: this model has been used to explain the vocational segregation of women and their under-representation in technology-related studies. The model proposes that the manifestation of a behaviour is the result of a multiplication of three components: the need for achievement (motives, MO), the probability of success (expectations, EX), and the incentive value (IV) of the task. People only enrol in studies that they believe they can succeed in because they have the skills and/or competencies to pursue them (expectations for success), and because they perceive them to have a high value (subjective task value).

- To measure these variables, in primary education, the response options were “Yes” and “No”, to ensure the subjects’ understanding and the reliability of their answers. At higher levels (secondary, university and graduates), the responses used consisted of a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

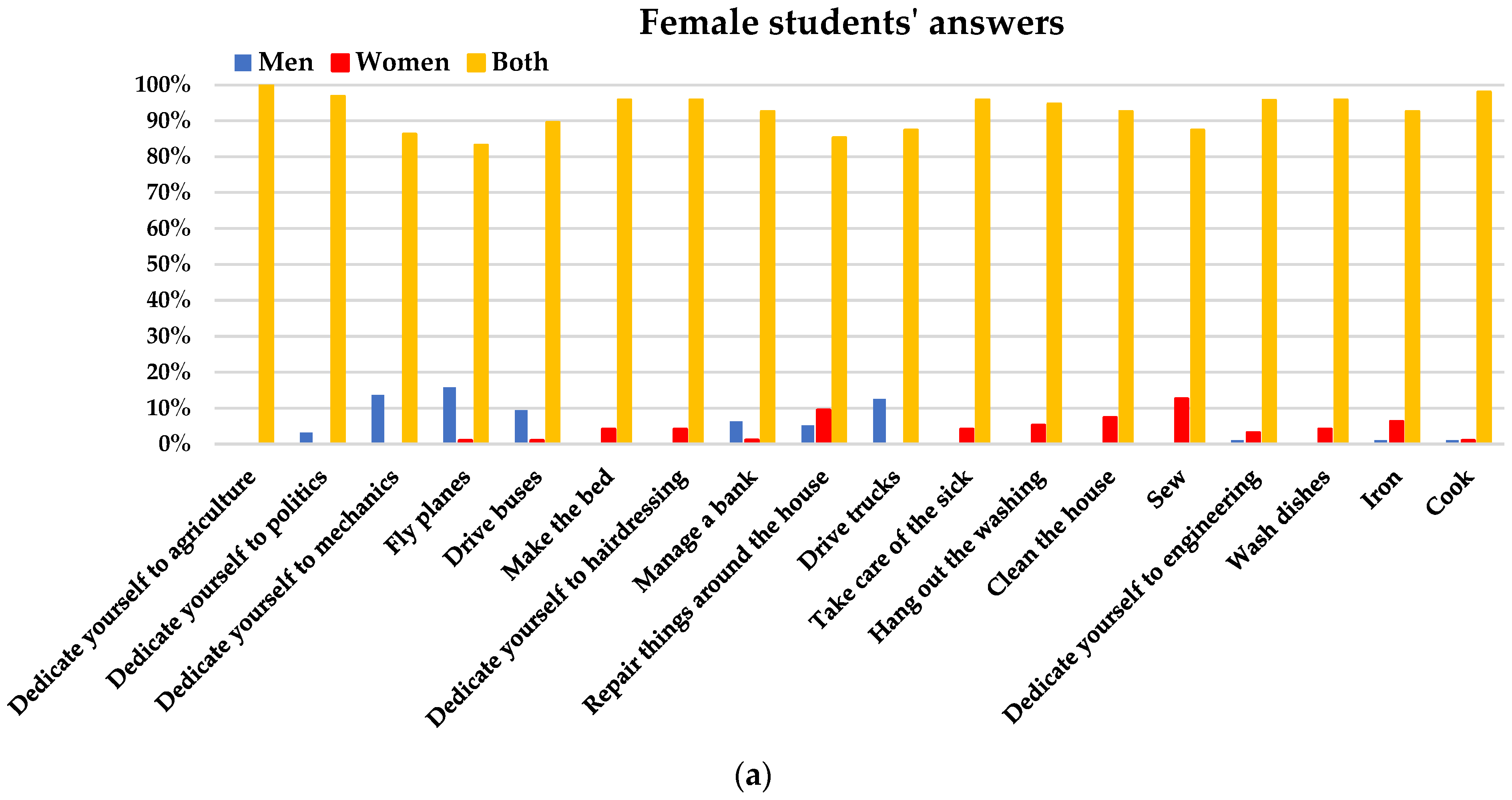

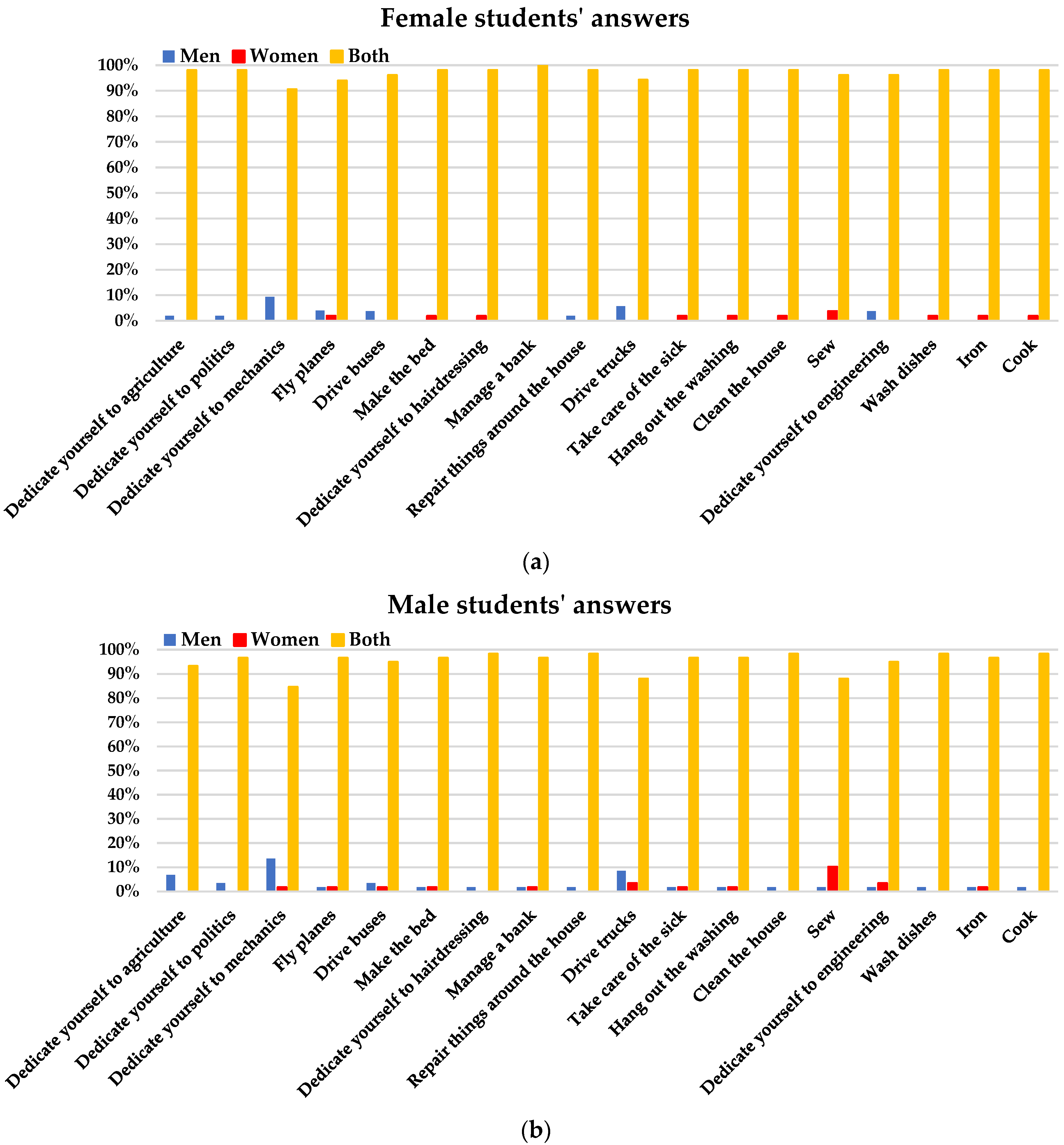

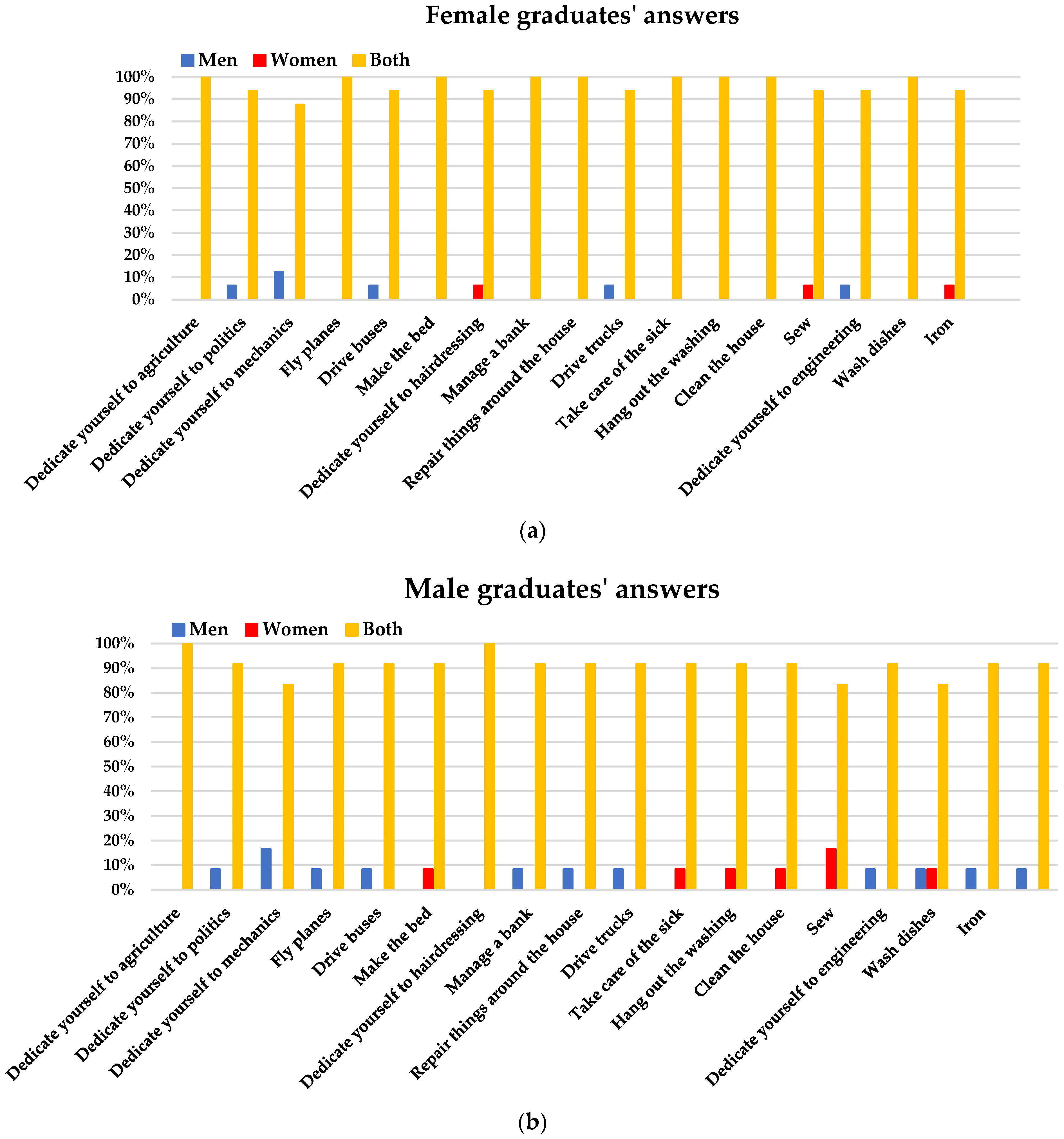

- Social role theory [27,28,29]: this model aims to highlight the sources of prejudice towards women in leadership positions. The goal of this model is to obtain information on participants’ beliefs about the tasks and activities they consider to be the domain of men, women or both. Socially, there is an incongruence between a woman’s traditional work role and a leadership position. This means that many women do not obtain leadership positions, or do not stay in them for long. Traditionally, women have had roles attributed to them that relate to care and emotions, while men have had roles attributed to them that relate to achievement, assertiveness and power.

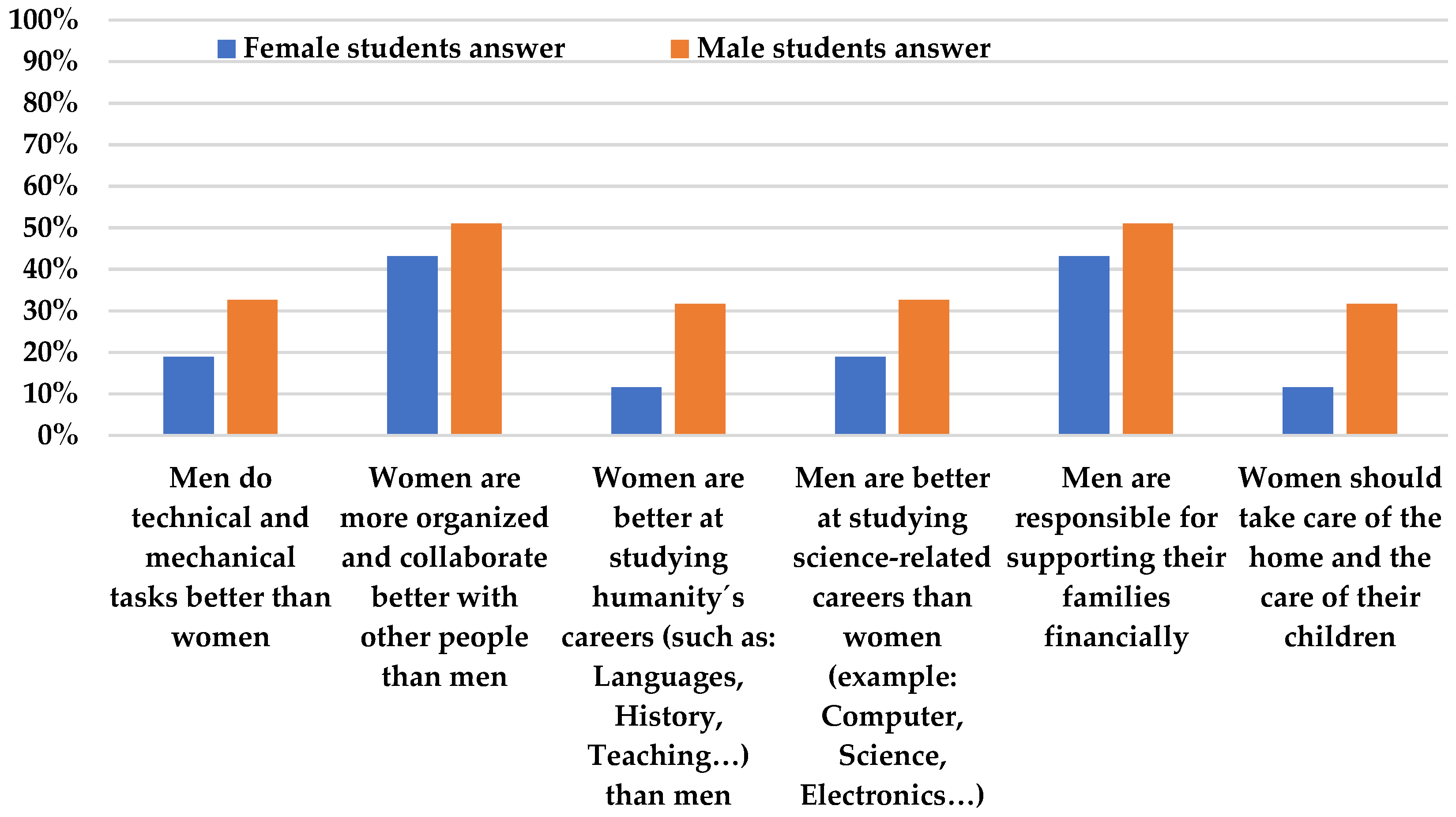

- Gender stereotypes theory [30,31,32,33]: this model explains that gender stereotypes have a multicomponent structure linked to personality traits, role-related behaviours and professions. This means that the closer the match between a person’s self-image and the prototypical image of someone working in a particular field, the more likely that person is to choose that profession. When applied to women, this means that they find few similarities between themselves and the prototypical image of a person working in the STEM field. The main cause of this problem is the lack of female role models in the scientific and technological fields, which does not encourage women to opt for these fields. For this purpose, the construct is made up of two components: stereotypes about competences and capabilities (SCC), and stereotypes about social responsibility (SSR).

- To measure these variables, in primary education, the response options were “Yes” and “No”, to ensure the subjects’ understanding and the reliability of their answers. At higher levels (secondary, university and graduates), the responses used consisted of a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

- The educational environment [34]: To identify possible structural problems and how the educational environment influences the selection of academic curricula from primary school to university, additional questions have been included in the surveys; these questions concern the number of laboratories in a given centre, the number of laboratory practices carried out, the use of inclusive language, etc.

2.1.2. Materials and Participatory Workshops

2.2. Inferential Statistics, and Reliability and Consistency Tests

3. Results

3.1. Primary Education Students

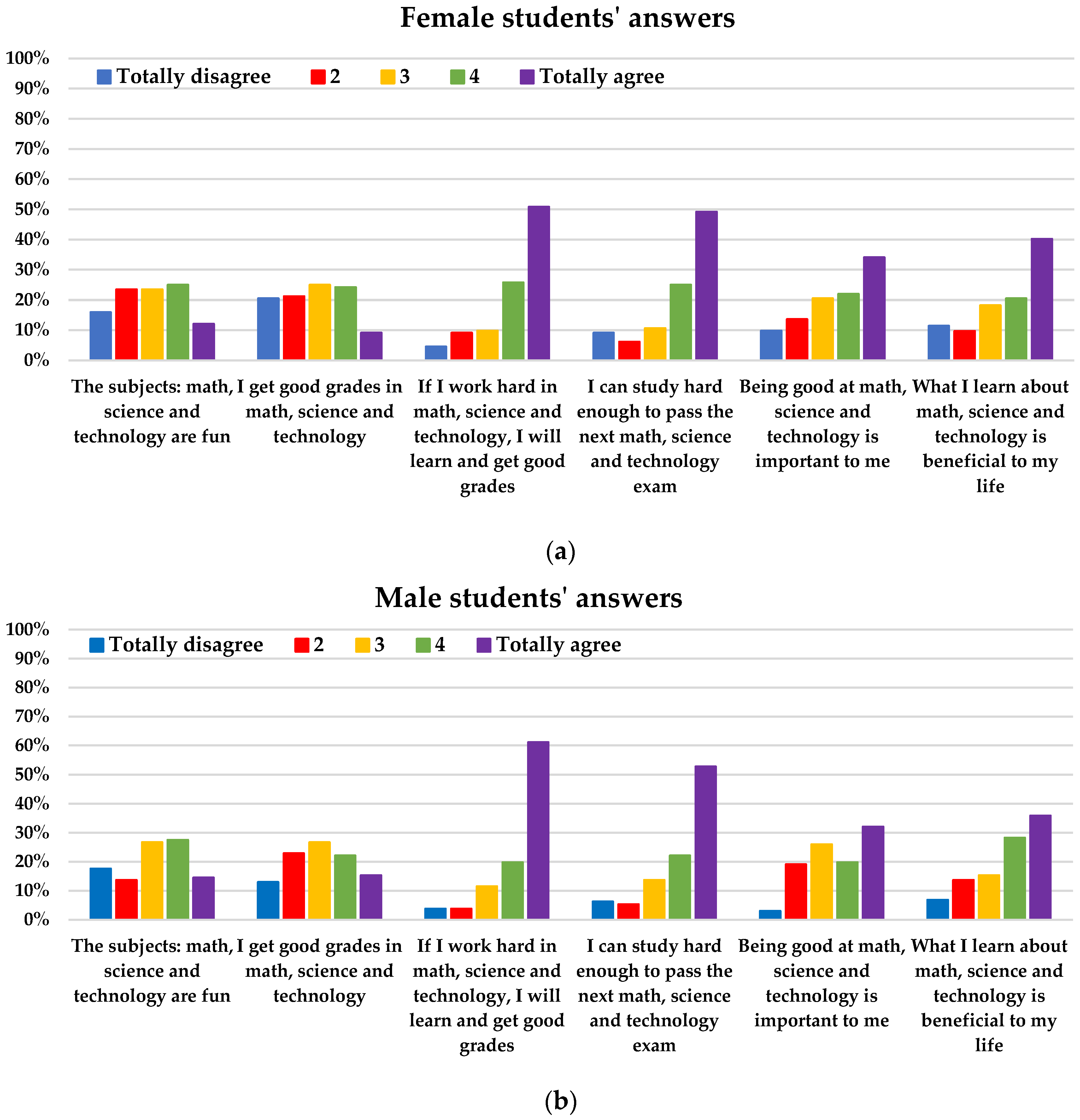

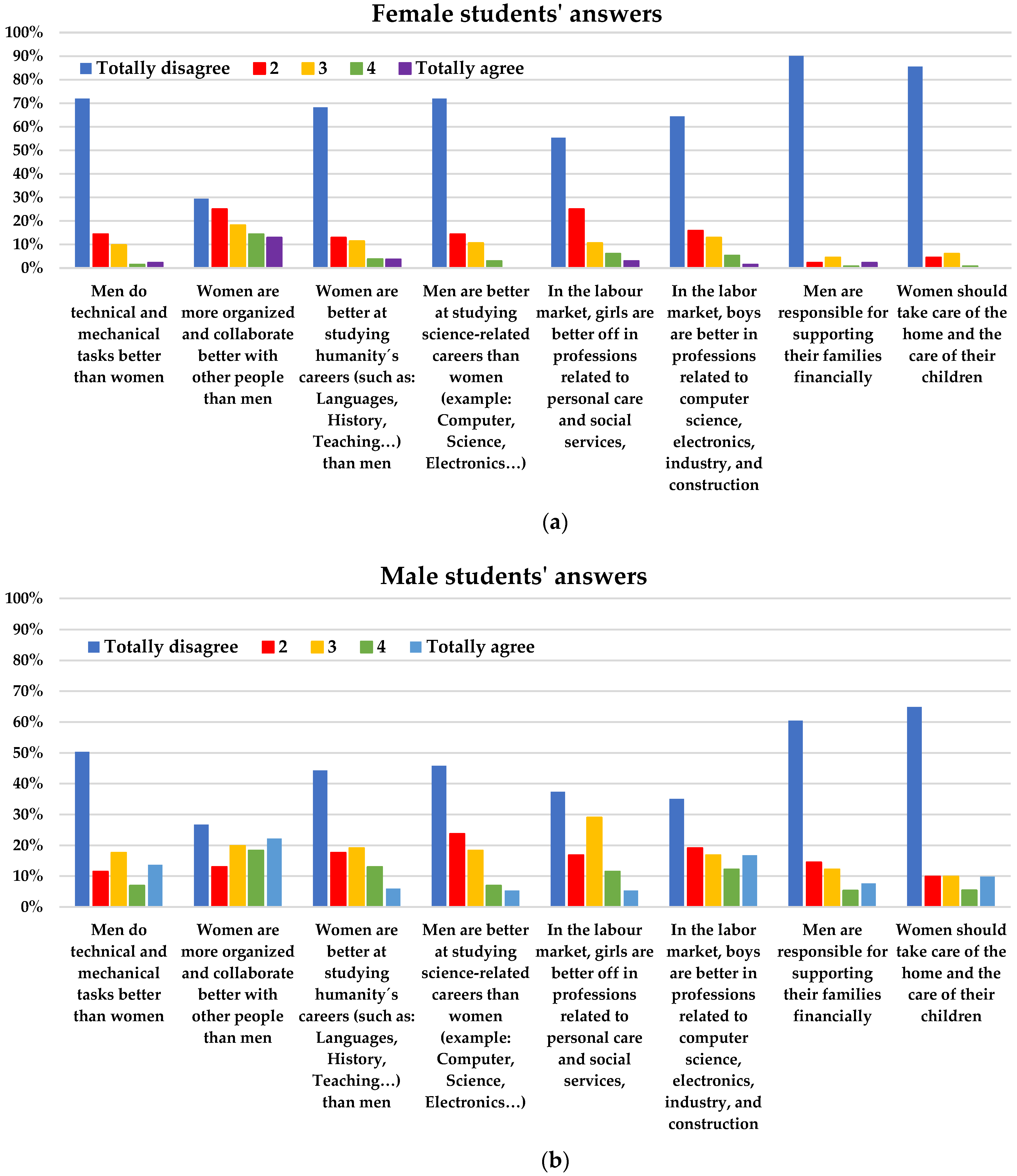

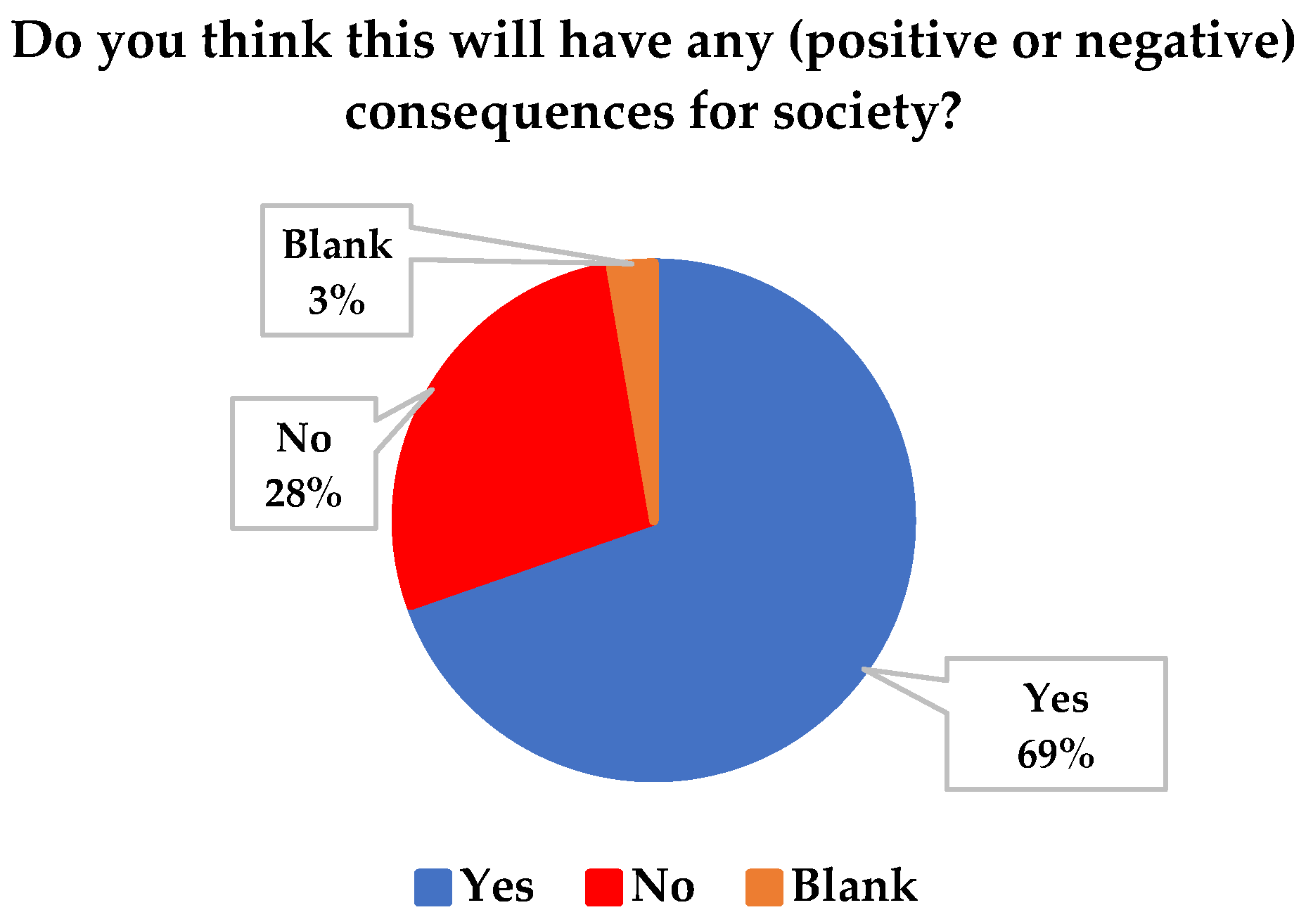

3.2. Secondary Education Students

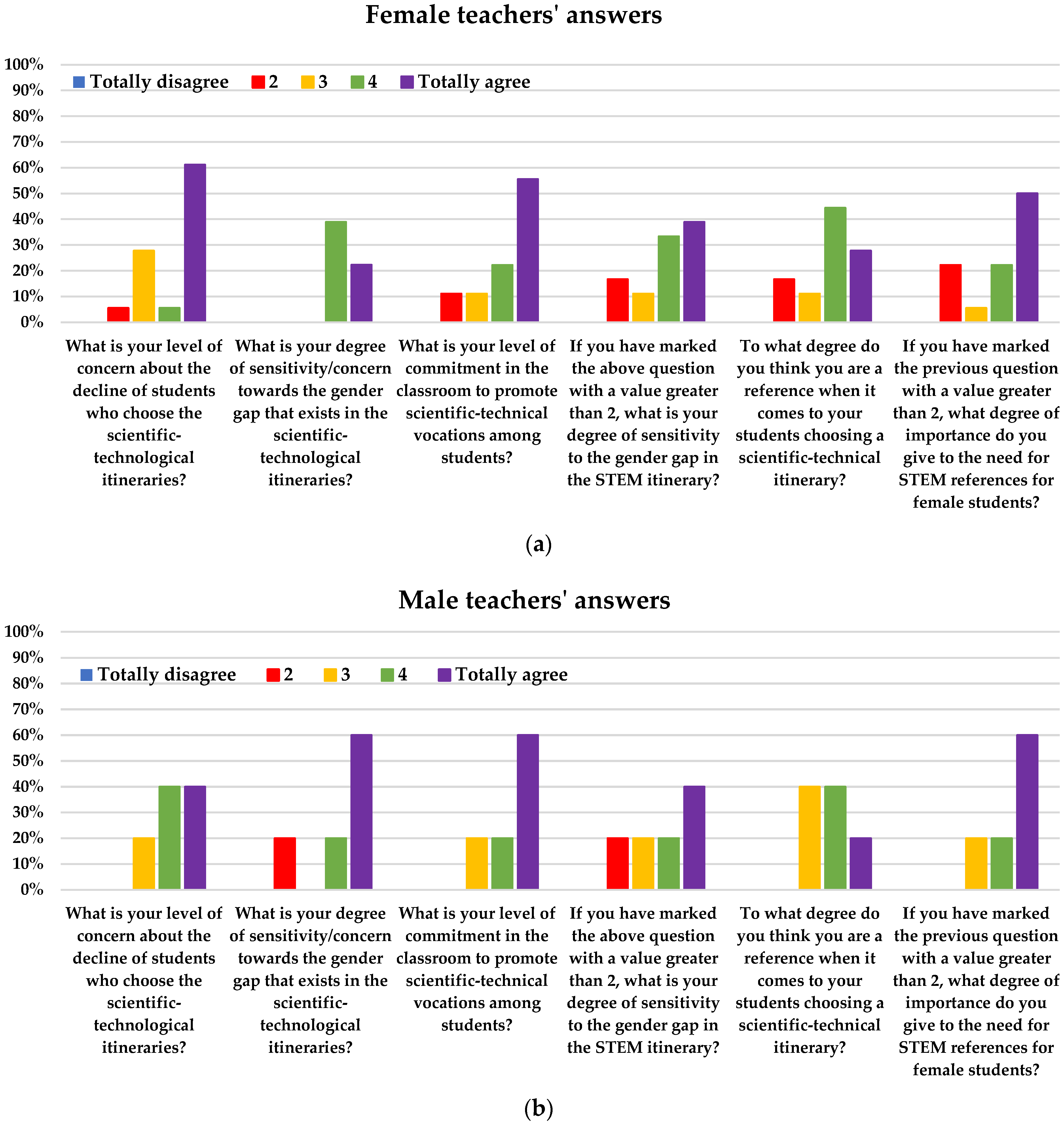

3.3. Primary and Secondary Teachers

3.4. University

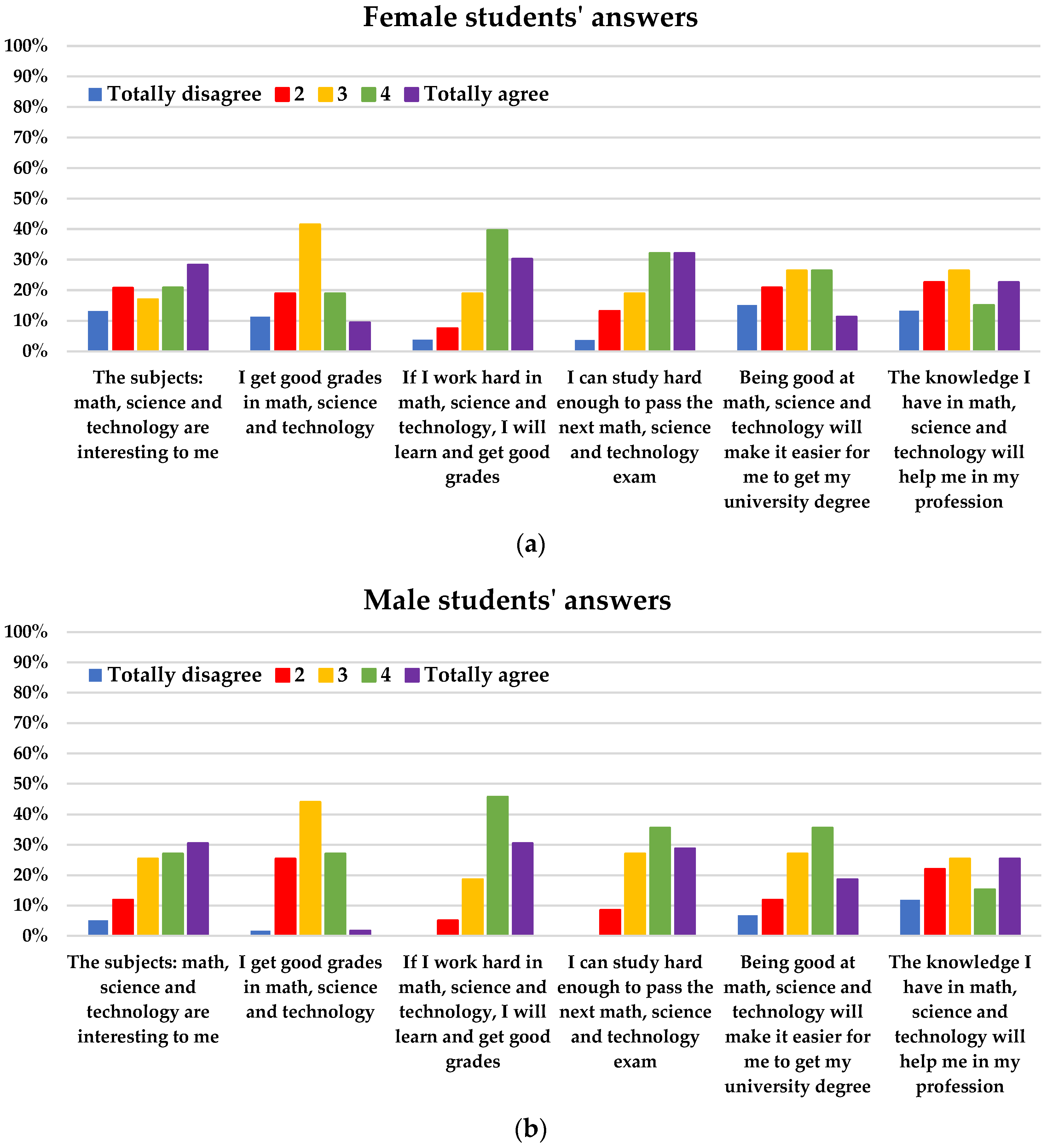

3.4.1. University Students

3.4.2. University Professors

3.5. University Graduates

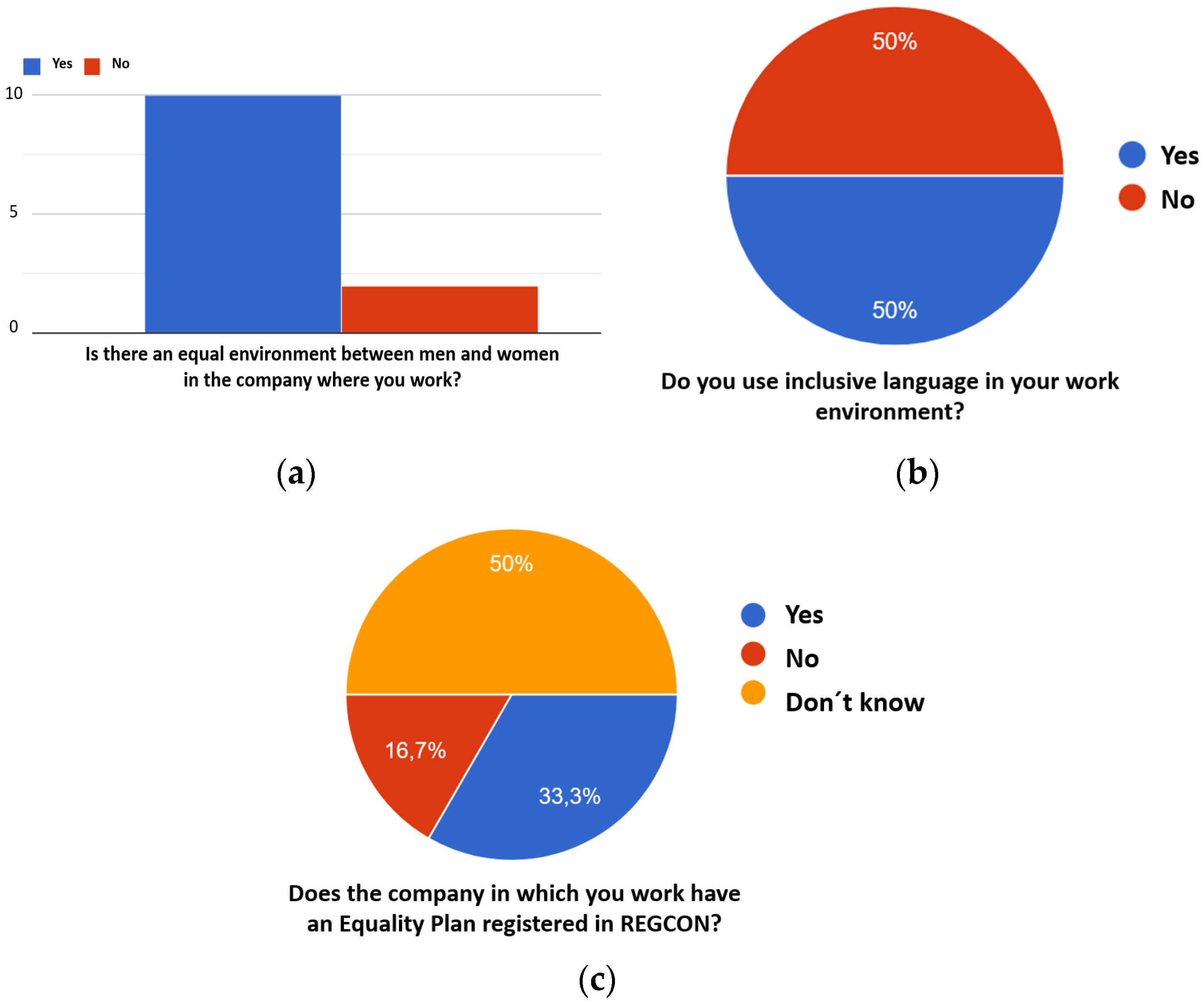

3.6. Enterprise/Industry Professionals

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Acronyms

| ALAS | Accompanying girLs towArds STEM careers |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| BEng | Bachelor of Engineering degree |

| CEDEFOP | European Center for the Development of Professional Vocation |

| EEA | European Education Area |

| EPWS | European Platform of Women Scientists |

| ERA | European Research Area |

| EU | European Union |

| GENERA | Gender Equality Network in the European Research Area |

| MS | Member state |

| PAU | University entrance exams |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics |

| UHU | University of Huelva |

| UNGA | United Nations General Assembly |

Appendix A

| Factorial Analysis | Primary Students | Secondary Students | University Students | University Graduates | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Load | AVE | Alfa | Mean (SD) | Load | AVE | Alfa | Mean (SD) | Load | AVE | Alfa | Mean (SD) | Load | AVE | Alfa | |

| Motives (MO) | ||||||||||||||||

| STEM subjects are fun | 4.22 (1.59) | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 3.01 (1.29) | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 3.49 (1.31) | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 3.93 (1.15) | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| I understand STEM subjects | 4.50 (1.33) | 0.85 | 3.14 (1.26) | 0.90 | 3.31 (1.09) | 0.93 | 3.64 (1.09) | 0.94 | ||||||||

| I get good grades in STEM subjects | 4.70 (1.06) | 0.64 | 2.92 (1.27) | 0.86 | 2.99 (0.96) | 0.80 | 3.57 (1.03) | 0.91 | ||||||||

| Expectations (EX) | ||||||||||||||||

| If I work hard in STEM subjects, I will learn and get good grades | 4.98 (0.28) | 0.71 | 0.54 | −0.18 | 2.66 (1.35) | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 3.94 (0.95) | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 4.18 (1.02) | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.78 |

| I can study hard enough to pass the next STEM subjects exam | 4.88 (0.67) | −0.71 | 4.20 (1.13) | 0.92 | 3.80 (1.05) | 0.90 | 3.93 (1.05) | 0.90 | ||||||||

| Incentive value (IV) | ||||||||||||||||

| Being good at STEM means a lot to me | 4.72 (1.03) | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 3.58 (1.27) | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 3.24 (1.21) | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 3.82 (1.06) | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.82 |

| Being good at STEM will help me in the rest of the years in my studies | 4.86 (0.74) | 0.76 | 3.99 (1.19) | 0.77 | 3.22 (1.4) | 0.81 | 3.46 (1.32) | 0.89 | ||||||||

| What we learn about STEM is beneficial to my life | 4.84 (0.79) | 0.64 | 3.58 (1.26) | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| The knowledge I have of STEM will help me in my future work | - | - | 3.70 (1.33) | 0.83 | 3.16 (1.53) | 0.74 | 3.25 (1.29) | 0.86 | ||||||||

| Stereotypes about competences and capabilities (SCC) | ||||||||||||||||

| Men are more qualified than women to do technical and mechanical tasks | 2.05 (1.76) | 0.75 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 1.15 (1.27) | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.87 | 1.63 (0.94) | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 1.43 (0.96) | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.83 |

| Women are better able to do organizational and cooperative tasks | 2.89 (2.00) | 0.55 | 2.76 (1.46) | 0.73 | 2.47 (1.37) | 0.68 | 1.89 (1.07) | 0.54 | ||||||||

| Girls’ performance is better in arts, humanities and social sciences majors | 1.88 (1.66) | 0.82 | 1.90 (1.22) | 0.80 | 1.7 (1.07) | 0.82 | 1.57 (1.17) | 0.91 | ||||||||

| The performance of boys is better in scientific-technical careers | 1.68 (1.51) | 0.76 | 1.73 (1.05) | 0.83 | 1.47 (0.82) | 0.78 | - | - | ||||||||

| In the labour market, girls are better in professions related to care and services | - | - | - | - | 2.03 (1.18) | 0.73 | 1.96 (1.15) | 0.69 | 1.61 (1.03) | 0.91 | ||||||

| In the job labour, boys are better at STEM professions | - | - | - | - | 2.10 (1.35) | 0.86 | 1.68 (0.96) | 0.81 | 1.64 (1.19) | 0.87 | ||||||

| Stereotypes about social responsibility (SSR) | ||||||||||||||||

| Men are responsible for supporting their families financially | 1.80 (1.61) | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 1.54 (1.09) | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 1.16 (0.61) | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 1.21 (0.83) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.1 |

| Women should take care of the house and their children. | 2.43 (1.92) | 0.86 | 1.58 (1.17) | 0.93 | 1.32 (0.88) | 0.85 | 1.21 (0.83) | 0.99 | ||||||||

Appendix B

| Secondary Students | University Students | University Graduates | ||||

| Mean (SD) Female | Mean (SD) Male | Mean (SD) Female | Mean (SD) Male | Mean (SD) Female | Mean (SD) Male | |

| Motives (MO) | ||||||

| STEM subjects are fun | 2.94 (1.27) | 3.08 (1.30) | 3.30 (1.42) | 3.66 (1.18) | 3.81 (1.17) | 4.08 (1.16) |

| I understand STEM subjects | 2.94 (1.27) | 3.34 (1.21) | 3.06 (1.20) | 3.54 (0.93) | 3.56 (1.15) | 3.75 (1.05) |

| I get good grades in STEM subjects | 2.80 (1.27) | 3.04 (1.26) | 2.96 (1.11) | 3.02 (0.82) | 3.50 (1.15) | 3.67 (0.88) |

| Expectations (EX) | ||||||

| If I work hard in STEM subjects, I will learn and get good grades | 4.09 (1.75) | 4.31 (1.07) | 3.85 (1.06) | 4.02 (0.84) | 4.19 (0.83) | 4.17 (1.27) |

| I can study hard enough to pass the next STEM subjects exam | 3.99 (1.29) | 4.10 (1.19) | 3.75 (1.16) | 3.85 (0.94) | 4.06 (0.93) | 3.75 (1.21) |

| Incentive (IV) | ||||||

| Being good at STEM means a lot to me | 3.57 (1.34) | 3.59 (1.21) | 2.98 (1.25) | 3.47 (1.14) | 3.63 (1.02) | 4.08 (1.08) |

| Being good at STEM will help me in the rest of the years in my studies | 3.97 (1.23) | 4.01 (1.15) | 2.96 (1.41) | 3.46 (1.36) | 3.19 (1.47) | 3.83 (1.03) |

| What we learn about STEM is beneficial to my life | 3.60 (1.31) | 3.56 (1.21) | - | - | - | - |

| The knowledge I have of STEM will help me in my future work | 3.68 (1.38) | 3.73 (1.27) | 3.11 (1.35) | 3.20 (1.36) | 3.19 (1.42) | 3.33 (1.15) |

| Stereotypes about competences and capabilities (SCC) | ||||||

| Men are more qualified than women to do technical and mechanical tasks | 1.48 (0.90) | 2.22 (1.47) | 1.64 (0.94) | 1.61 (0.95) | 1.19 (0.54) | 1.75 (1.29) |

| Women are better able to do organizational and cooperative tasks | 2.56 (1.38) | 2.96 (1.51) | 2.45 (1.29) | 2.49 (1.45) | 2 (1.03) | 1.75 (1.14) |

| Girls’ performance is better in arts, humanities and social sciences majors | 1.62 (1.07) | 2.19 (1.30) | 1.66 (1.02) | 1.73 (1.13) | 1.50 (1.09) | 1.67 (1.30) |

| The performance of boys is better in scientific-technical careers | 1.45 (0.80) | 2.02 (1.19) | 1.40 (0.72) | 1.54 (0.90) | ||

| In the labour market, girls are better in professions related to care and services | 1.77 (1.06) | 2.31 (1.23) | 1.91 (1.11) | 2 (1.19) | 1.50 (1.09) | 1.75 (0.96) |

| In the job labour, boys are better at STEM professions | 1.64 (1) | 2.56 (1.49) | 1.64 (0.94) | 1.71 (0.98) | 1.44 (0.81) | 1.92 (1.56) |

| Stereotypes about social responsibility (SSR) | ||||||

| Men are responsible for supporting their families financially | 1.23 (0.77) | 1.85 (1.27) | 1.08 (0.27) | 1.24 (0.79) | 1 (0) | 1.50 (1.24) |

| Women should worry about the house and taking care of their children. | 1.31 (0.87) | 1.85 (1.36) | 1.19 (0.52) | 1.44 (1.10) | 1 (0) | 1.50 (1.24) |

Appendix C

| χ2 Gender | ||||

| Primary Students | Secondary Students | University Students | University Graduates | |

| Motives (MO) | ||||

| STEM subjects are fun | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.57 |

| I understand STEM subjects | 0.69 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.54 |

| I get good grades in STEM subjects | 0.65 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.65 |

| Expectations (EX) | ||||

| If I work hard in STEM subjects, I will learn and get good grades | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 0.48 |

| I can study hard enough to pass the next STEM subjects exam | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.43 | 0.30 |

| Incentive value (IV) | ||||

| Being good at STEM means a lot to me | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.12 |

| Being good at STEM will help me in the rest of the years in my studies | 0.79 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.59 |

| What we learn about STEM is beneficial to my life | 0.90 | 0.13 | - | - |

| The knowledge I have of STEM will help me in my future work | - | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.59 |

| Social Role (SR) | ||||

| Who would these activities correspond to men, women or both? Engage in agriculture | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.21 | - |

| … Politics | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.35 |

| … Mechanics | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.75 |

| … Fly planes | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 0.24 |

| … Drive buses | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.83 |

| … Do housework | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.24 |

| … Engage in hairdressing | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.38 |

| … Head a bank | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0.24 |

| … Repair devices at home | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.94 | 0.24 |

| … Drive trucks | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.83 |

| … Take care of sick | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.24 |

| … Hang out the washing | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.24 |

| … Cleaning the house | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.24 |

| … Sew the clothes | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.38 |

| … Engage to engineering | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.83 |

| … Washing the dishes | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.24 |

| … Ironing | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.83 |

| … Cooking | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.37 | 0.24 |

| Stereotypes about competences and capabilities (SCC) | ||||

| Men are more qualified than women to do technical and mechanical tasks | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.48 |

| Women are better able to do organizational and cooperative tasks | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.38 |

| Girls’ performance is better in arts, humanities and social sciences majors | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.52 |

| The performance of boys is better in scientific-technical careers | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.64 | - |

| In the labour market, girls are better in professions related to care and services | - | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.26 |

| In the job labour, boys are better at STEM professions | - | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.21 |

| Stereotypes about social responsibility (SSR) | ||||

| Men are responsible for supporting their families financially | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.24 |

| Women should worry about the house and taking care of their children. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.24 |

References

- Marchisio, M.; Barana, A.; Fissore, C.; Pulvirenti, M. Digital Education to Foster the Success of Students in Difficulty in Line with the Digital Education Action Plan. EDEN Conf. Proc. 2021, 1, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiadou, N.; Rambla, X. Education policy governance and the power of ideas in constructing the new European Education Area. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 4, 14749041221121388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, I. Referentiality mechanisms in EU education policymaking: The case of the European Education Area. Eur. J. Educ. 2022, 57, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Ordóñez, R. ALAS: Accompanying girls towards STEM careers. An experimental study from primary to higher education. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE Eurasian Conference on Educational Innovation, Singapore, 3–5 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Ceada, Y.; Martín, M.J. Study on the Low Presence of Women in the STEM field. Search for Reasons to Be Able to Increase Participation. In Proceedings of the V Jornadas ScienCity 2022. Fomento de la Cultura Científica, Tecnológica y de Innovación en Ciudades Inteligentes, Huelva, Spain, 14–16 November 2022; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría General de Universidades. Datos y Cifras del Sistema Universitario Español. Publicación 2021–2022. In Datos y Cifras. 2022. Available online: https://www.universidades.gob.es/stfls/universidades/Estadisticas/ficheros/DyC_2021_22.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Langdon, D.; McKittrick, G.; Beede, D.; Khan, B.; Doms, M. STEM: Good Jobs Now and for the Future. In ESA Issue Brief #03-11. 2011; pp. 37–49. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED522129 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Fallis, A. Encouraging STEM Studies for the Labour Market. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment Projections. 2022. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/stem-employment.htm (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Tres Bishop, D. The Hard Truth About Soft Skills. Muma Bus. Rev. 2017, 1, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mely, W.; Br, B.; Nirwana, D.; Manulang, R. The Effect of Organizational Learning on Improving Hard skills, Soft Skills, and Innovation on Performance. J. Prajaiswara 2022, 3, 126–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schislyaeva, E.R.; Saychenko, O.A. Labor Market Soft Skills in the Context of Digitalization of the Economy. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.S.; Piña, A.A. Strategically Addressing the Soft Skills Gap Among STEM Undergraduates. J. Res. STEM Educ. 2021, 7, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attström, K.; Niedlich, S.; Sandvliet, K.; Kuhn, H.-M.; Beavor, E. Mapping and Analysing Bottleneck Vacancies in EU Labour Markets—Overview Report. 2014, p. 122. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eures/downloadSectionFile.do?fileId=8010 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- García-Holgado, A.; Verdugo-Castro, S.; González, C.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.C.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. European Proposals to Work in the Gender Gap in STEM: A Systematic Analysis. IEEE Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Aprendiz. 2020, 15, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, A. The role of cultural contexts in explaining cross-national gender gaps in STEM expectations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2016, 32, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Holgado, A.; Mena, J.; García-Peñalvo, F.J.; Pascual, J.; Heikkinen, M.A.; Harmoinen, S.; García, L.; Niebles, R.P.; Amores, L. Gender equality in STEM programs: A proposal to analyse the situation of a university about the gender gap. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Porto, Portugal, 27–30 April 2020; Volume 21, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dulce-Salcedo, O.V.; Maldonado, D.; Sánchez, F. Is the proportion of female STEM teachers in secondary education related to women’s enrollment in tertiary education STEM programs? Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 91, 102591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. Women in STEM: Ability, preference, and value. Labour Econ. 2021, 70, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.C.; Haber, A.S.; Ghossainy, M.E.; Barbero, S.; Corriveau, K.H. The impact of visualizing the group on children’s persistence in and perceptions of STEM. Acta Psychol. 2023, 233, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaweł, A.; Krstić, M. Gender Gaps In Entrepreneurship And Education Levels From The Perspective Of Clusters Of European Countries. J. Dev. Entrep. 2021, 26, 2150024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R.; Groot, E.V. De Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom. J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. 1997. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-08589-000 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Expectancy–Value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Freedman-Doan, C.; Frome, P.; Jacobs, J.; Yoon, K.S. Gender-role socialization in the family: A longitudinal approach. In The Developmental Social Psychology of Gender; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 333–360. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W. Social role theory. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 2, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation; John, M., Ed.; MacEachran Memorial Lecture Series; 1985; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Wood, W.; Diekman, A.B. Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In The Developmental Social Psychology of Gender; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 123–174. [Google Scholar]

- Deaux, K.; Lewis, L.L. Structure of gender stereotypes: Interrelationships among components and gender label. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaux, K.; Winton, W.; Crowley, M.; Lewis, L.L. Level of categorization and content of gender stereotypes. Soc. Cogn. 1985, 3, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáinz, M.; Meneses, J.; López, B.-S.; Fàbregues, S. Gender Stereotypes and Attitudes Towards Information and Communication Technology Professionals in a Sample of Spanish Secondary Students. Sex Roles 2016, 74, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannover, B.; Kessels, U. Self-to-prototype matching as a strategy for making academic choices. Why high school students do not like math and science. Learn. Instr. 2004, 14, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturrock, G.R.; Zandvliet, D.B. Citizenship Outcomes and Place-Based Learning Environments in an Integrated Environmental Studies Program. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vacancies at ISCO 4-Digit Level | Vacancies at ISCO 2-Digit Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Specific Occupation | Rank | Specific Occupation |

| 7 | Mechanical engineers | 2 | Science and engineering professionals |

| 8 | Software developers | 3 | Information and communications technology professionals |

| 12 | Electrical engineers | 7 | Science and engineering associate professionals |

| 14 | Civil engineers | 14 | Electrical and electronic trade workers |

| Reference | Scope | Target Group (1) | Academic Year | Survey Analysis Tool | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors’ proposal | National and international (Spain and the Czech Republic) | Primary education (Students and teachers) | Third and fourth year | Model 1: Expectancy–Value Theory of Motivation Model 2: Social Role Theory Model 3: Gender Stereotypes Theory | Renewable Energies, Industrial Electronics and Chemical Engineering participatory workshops |

| National and international (Spain and Italy) | Secondary education (Students and teachers) | Fifth and sixth year | Renewable Energies, Industrial Electronics and Chemical Engineering participatory workshops | ||

| National and international (Spain, Italy, Austria and the Czech Republic) | University (Students and professors) | All | - | ||

| National (Spain) | University graduates | All | - | ||

| National (Spain) | Enterprise/industry professionals | All | - | ||

| [16] | International | Secondary education | 15 and 16 years old | International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO) World Bank and European Values Survey (EVS) Item Response Theory | - |

| [17] | National and International | University | All | UNESCO SAGA Toolkit | - |

| [18] | National (Bogotá) | Secondary education | All | - | - |

| [19] | National (University of Purdue) | University graduates | All | First Destination Survey American Community Survey National Survey of College Graduates | - |

| [20] | National | Preschool | 4–6 years old | Attribution theory | - |

| [21] | International (European countries) | Youth, higher education, adult learning and STEM education | 15–30 years old | European Union Labor Force Survey (EU-LFS) | - |

| Is there a STEM lab in your school? | Yes (%) | No (%) |

| 16.60% | 83.40% | |

| How many times have you gone to the lab? | Less than 10 (%) | More than (%) |

| 98.50% | 1.50% | |

| Science teacher’s gender | Male (%) | Female (%) |

| 12.60% | 87.40% | |

| Mathematics teacher’s gender | Male (%) | Female (%) |

| 21.10% | 78.90% |

| Is there a STEM lab in your high school? | Yes (%) | No (%) |

| 88.20% | 11.80% | |

| How many times have you been to the lab? | Less than 10 (%) | More than (%) |

| 75.30% | 24.70% | |

| Science teacher’s gender | Male (%) | Female (%) |

| 32.70% | 67.30% | |

| Mathematics teacher’s gender | Male (%) | Female (%) |

| 57% | 43% | |

| Technology teacher’s gender | Male (%) | Female (%) |

| 63.10% | 36.90% |

| Female Students’ Responses | Male Students’ Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEM (%) | No STEM (%) | STEM (%) | No STEM (%) | |

| Family influence | 18.8% | - | 2.63% | - |

| Vocation | 54.55% | 88.10% | 55.26% | 71.43% |

| Previous curricular itinerary | 9.09% | 11.90% | 2.63% | 4.76% |

| Obligation | - | - | 5.26% | - |

| Professional opportunities | 18.18% | - | 34.21% | 19.05% |

| Dk/Da | - | - | - | 4.76% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez, M.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Ceada, Y. The Gender Gap in STEM Careers: An Inter-Regional and Transgenerational Experimental Study to Identify the Low Presence of Women. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070649

Martínez M, Segura F, Andújar JM, Ceada Y. The Gender Gap in STEM Careers: An Inter-Regional and Transgenerational Experimental Study to Identify the Low Presence of Women. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(7):649. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070649

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez, Macarena, Francisca Segura, José Manuel Andújar, and Yolanda Ceada. 2023. "The Gender Gap in STEM Careers: An Inter-Regional and Transgenerational Experimental Study to Identify the Low Presence of Women" Education Sciences 13, no. 7: 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070649

APA StyleMartínez, M., Segura, F., Andújar, J. M., & Ceada, Y. (2023). The Gender Gap in STEM Careers: An Inter-Regional and Transgenerational Experimental Study to Identify the Low Presence of Women. Education Sciences, 13(7), 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070649