Abstract

This paper aims to conceptualise processual employability with identity theory to reflect the amorphous and developmental nature of employability. Through literature review, we propose a model demonstrating how the career identity emergence process is linked with processual employability behaviour through four stages of identity change: Identity Enactment, Identity Validation, Identity Construction, and Identity Exploration. Each stage is driven by the tension between the individual’s current career identity and the experienced social interactions with a changing Individual–World of Work Interface, which eventually constitutes an iterative process of employability suitable for the individual career context. It thus clarifies how the pursuit of an achieved career identity drives processual employability in a fast-changing social context and provides a holistic view of employability as a journey of identity changes. This review responds to the call for integrating developmental and sustainable views into employability and also enriches identity-based employability theories.

1. Introduction

Modern society brings uncertainty and fluidity to the World of Work (WoW), with fast-paced changes, volatile professions, as well as disruptive and shifting standards for being employable [1,2,3,4,5]. This situation raises a challenge to the traditionally dominating approach of possessional employability [6]. In this approach, employability is often defined as the possession of certain characteristics, skills, or capabilities [6,7], and the emphasis is often on the needs of the job market [8] viewed from a cross-sectional instead of a longitudinal perspective [9]. As a result, the employability concept gradually bears too many meanings [10,11] to effectively represent itself [12]. Therefore, more attempts to redefine employability by viewing it as a contextualised and developing process comprising actions and decisions that engage with and navigate through an emerging journey on the Individual–WoW Interface (IWI) [6,7,9,13,14,15,16,17,18]. While the destination could vary, every journey contains adaptive actions that situate the individual into their particular career context [16], in which they are willing to pursue what they value [9,19,20], and in which such pursuit is achieved by continuous self-development in capabilities and understanding of their own career [18,21,22]. This process would eventually result in the individuals being socially ascribed as employable [6,9,13] and, therefore, result in a higher chance of employment [19,23]. Such is the discourse of processual employability.

The key theme in processual employability is career identity. Previous research has indicated how career identity could play a role in employability as a compass of career-related actions [24], an enabler of self-direction and value-orientation [20], and a career capital [25] or disposition [26] that benefits the acquisition or maintaining of employment. However, as the underpinning factor of employability [10], a synthesised model is missing to explain how career identity is positioned in processual employability, so the latter can be understood as a social construct [9]. This gap prevents a deeper understanding of employability from a holistic perspective that combines proactive behaviours [6,7] with a developmental perspective [27] that reflects the dynamic and context-sensitive nature of the employability [13,16]. The relationship with the individualised IWI context also needs to be embedded, since career identity cannot be separated from the social context [28]. Such efforts could shed light on practical issues, for example, how processual employability may be enhanced by assessing and fostering a mature career identity [27,29]. In general, a theoretical explanation of how career identity plays its role in processual employability facing the changing social context is needed.

This conceptual paper aims to bridge the above gap by explaining processual employability via identity theory. Specifically, this paper focuses on the following questions:

- How is career identity positioned in the construct of processual employability?

- How does the change of career identity result in processual employability through identity work?

We build on the previous discussions that define employability as the achievement of a career identity [6,13] to illustrate processual employability as a structure supported and driven by career identity emergence with the individual’s interactions in the IWI. To do this, we place career identity in a position as both the reason and the result of one’s lived experience conducting processual employability behaviours and map the career identity emergence process with processual employability behaviours by connecting them with various forms of “identity work”—the activities people do to enact, form, repair, maintain, strengthen, or revise their identity in a context [30,31]. Eventually, we arrive at a conceptual model with four stages of identity change, namely, Identity Enactment, Identity Validation, Identity Construction, and Identity Exploration. Each stage is driven by the tension between the individual’s current career identity and the lived experiences conducting processual employability behaviours. Together, they form an iterative process with continuously adapting career identity that the individual enact as they grow into an environment [32] where they are most employable.

Our model provides a holistic view of processual employability with career identity emergence as an interactive [13] and evolving core responding and interdependent to the changing IWI [33]. It hence conceptualises the amorphous and fluid nature of employability. Our model enriches the identity-based employability theories [6,13] and can be seen as an alternative perspective for achieving sustainable employability [9,18]. To some degree, our theory also mitigates the divide between the discourses of processual employability and possessional employability [7] by embedding a developmental view on employability capitals [25,27]. Practically, our model can provide a foundation to examine the barriers to processual employability via a career identity perspective. It could benefit higher education and career practitioners in analysing how individual employability could be improved through facilitating and nurturing a mature career identity.

2. Employability as a Process: An Emerging Journey through the Misty Wilderness

Although lacking a detailed construct, researchers agree that processual employability constitutes activities led by proactive decisions and actions that pave pathways towards employment success [6,7,13,14]. Hence, processual employability is about enabling the individual’s proactive and adaptive behaviours to interact with their particular IWI context [16]. The IWI is a complex system that constitutes various contextual components—elements of employment opportunities and events [16,34,35]. Because contextual components are under various, dynamic, and unforeseeable influences from a tremendously complex system of the WoW [34], the IWI, therefore, forms an unpredictable and unique social context for each individual to travel through according to their own provision of employability. Phenomenon-wise, this is shown in forms that vary across time and space, for example, the changing and complicated information about the job market, the individual differences in interpreting these signals caused by diversities in the social, cultural, and economic background, and the activities that interact with the mix of the above. Therefore, the individual’s lived experiences interacting with the contextual components [36] would feel less like a clearly-routed movement to a clearly-identified destination, in which employability is about clarifying the target and persists through obstacles by gaining the needed employability attributes [37]. Rather, such a journey is perceived more as a short-sighted person fumbling in a misty wilderness, facing an emerging journey from beyond the known and anticipatable realm [15,36]. The destination of this journey, in this case, is increasingly self-defined by the internalised reference system of the individual.

In this case, individuals do not, and cannot, acquire enough relevant information to clearly plan and persistently implement the journey [38]. Instead, the change is increasingly dependent on an identity that acts as the anchor for being adaptive while staying focused, being resilient while facing negative emotions, and having well-being in uncertainty and complexity [39,40]. Identity also provides motivation [41] to engage with the dynamic and non-linear process in capturing contextual possibilities [42]; the sense of coherence, continuity, distinctiveness [43], and self-positioning in a social context [42,44]; and, in general, higher well-being [45]. This makes career identity the core part of processual employability, as the latter focuses on generating a process that creates personally meaningful and feasible career pathways, mitigates existing individual and environmental differences [7,14], and provides psychological success to sustain the process [20,46].

In the next sections, we will first review the proactive career behaviours that outline processual employability and then discuss the career identity emergence process in relation to these behaviours. Such discussions will illustrate how career identity both supports proactive career behaviours, and, is being constructed by the experience of conducting such behaviours.

3. Career Identity: The “Alpha and Omega” of Processual Employability

Career identity is the concepts and narratives that individuals use in a career-related context to define their roles. Therefore, career identity acts as a compass of, and motivation for, adaptive behaviours [24,47]. We position career identity as the core of processual employability, because career identity is the “Alpha and Omega” of processual employability: It is both the beginning and the end, both the result of and the reason for engaging with the changing IWI.

On the one hand, career identity is the reason for proactive career behaviour and, therefore, the beginning of processual employability. Career identity motivates actions and decision-making as individuals seek to bind their personal identity to the social identity in the career context [30]. As individuals seek to be accepted by a social group by establishing social bounds, behavioural changes that lead to employability are achieved through socialisation [48]. In this process, career identity provides concepts and narratives to interpret perceptions of the social activities that inform actions [10,49], shape graduates’ understanding of their experience, and lead to proactive behaviours pursuing emerging possibilities from the social environment [15,50,51]. In this case, career identity acts as the motivation for processual employability in the form of identity work—the individual pursues an achieved career identity which they proactively claim by changing behaviours and seeking a career context that affirms it [6,13]. Therefore, career identity drives proactive actions and decisions that constitute the processual employability [7].

On the other hand, career identity is changed by the lived experience of processual employability behaviours [36] and, therefore, the final result of processual employability. During their engagement with the IWI, individuals enact their career identity by conducting processual employability behaviours, which creates the social interactions they live in [32,52]. This is perceived as the claim for a career identity to be affirmed and ascribed by the career context the individual is trying to be part of [6,13]. These experiences of identity claim and affirmation inform the explorations and reasonings about one’s career identity [41,53,54]. As such, the ongoing interactions with the IWI deliver perceptions of the changing context by creating tension between the existing career identity and the perceived social affirmation [47,55,56]. This stimulates an adapted career identity to emerge as a response to the changing social context. Career identity therefore evolves until it reaches a grounded, mature, and stable form in a career context, in which the individual is able to show confidence and reliability [53,57].

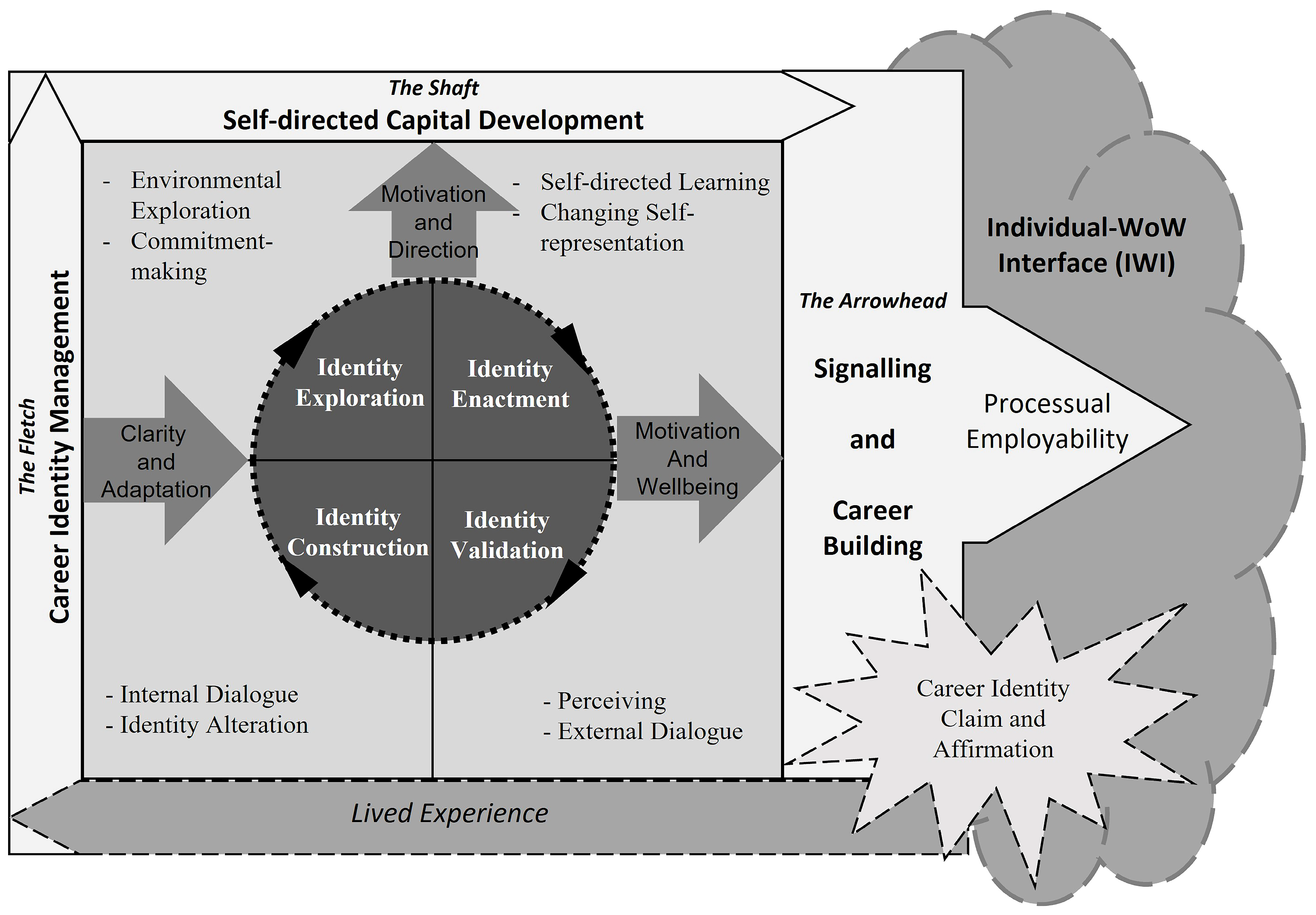

Therefore, social interactions with the IWI would eventually guide an individual into a balanced status between their career identity and the career role they attempt to enter. In such balance, the individual achieves a stable career identity which directs practices and decisions that are perceived as performance excellence in a career context [6,58], and in turn, the achieved career identity is enhanced [31]. This marks the achievement of employability for the particular IWI at a certain time and place until the next transition is required by the change in contextual components. In such cases, unbalanced experiences in identity work challenge the existing career identity, and individuals are again pressed to act so such tension can be eased and alter their career identity to bind themselves with the changed social context [30,31]. On that basis, we use career identity change as an interactive core to understand processual employability and the individual transition from different points in time, space, and, therefore, career-related social context. We then expand the discussion to the specific connections between the career identity emergence process and the processual employability behaviours, which is integrated into a conceptual model that puts all these elements into the bigger picture of Individual–WoW interactions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Career identity emergence positioned as the interactive core of processual employability.

4. Processual Employability Behaviours in Relation to Career Identity

The concept of processual employability informs several types of activities to navigate through the dynamic and uncertain IWI into the WoW. In our model, this transition is similar to an arrow (processual employability) shot into the turbulent air (the IWI) aiming to hit birds (employments) flying fast and with changing sizes at various distances (the dynamic and unpredictable WoW). Every arrow is made with different materials (individual differences in the possession of employability attributes [7]), shot at various speeds and angles (individual differences in social and positional status [7]) into unpredictable turbulences (the changing composition of contextual components on the IWI). Therefore, it is not feasible to state what trajectory an arrow would or should take to hit which bird. However, if the arrow transforms as fit to the turbulence and keeps creating new trajectories it deems correct, it will catch a bird that is most suitable at each end of the trajectories.

We compare the structure of an arrow with that of processual employability behaviours. An arrow constitutes three major parts: the arrowhead that opens up a way in the water, the shaft that bears the arrowhead, and the fletch that stabilises the trajectory according to the turbulence. Just like an arrow, processual employability also comprises three major types of behaviours: Signalling and Career Building, Self-directed Capital Development, and Career Identity Management. We will then specify and explain the behaviours attached to each part of this “arrow” and link them with career identity, respectively, so career identity’s positioning in relation to processual employability can be clarified.

4.1. The Arrowhead—Signalling and Career Building

The arrowhead enables the arrow to open a way in the air. This aspect of processual employability encompasses Signalling and Career Building, which are involved in direct social interactions with the IWI (see Figure 1). Signalling is the interactive social activity conducted by the individual to deliver messages about their employability characteristics, typically personal capitals (defined in Section 4.2), so their career identity could be perceived, understood, and potentially ascribed as “employable” by others [35,59]. One would have a higher chance of employment if social affirmation of their career identity is achieved [6,13]. Career Building is the information-seeking, channel-building, or opportunity-creating behaviours for Signalling to take place [35,60], such as environment exploration and networking [7].

The specific approaches that one takes to implement these behaviours and/or set up a target could vary depending on individual conditions. However, these behaviours could all be considered as part of identity work [30,31], because the achieving of this goal is dependent on the enaction of a career identity that displays the appropriate career-role characteristics (various across each individual) and in pursuit of the identity to be accepted as part of a wider career identity community [6,31,58]. In this way, the pursuit of one’s career identity to be socially ascribed motivates an individual to create pathways towards a career role [6,13]. Therefore, career identity serves as the motivation to proactively engage with Signalling and Career Building activities, as well as the compass for actions in Signalling.

4.2. The Shaft—Self-Directed Capital Development

The shaft of the arrow bears the arrowhead, so it can be shot by a bow. This aspect in processual employability is captured by the development of personal capital—a combination of personal resources that benefits the individual’s value-creating functions in society and enhances their chance to maintain or acquire employment [8,58,61]. Since the fulfilment of economic needs is the premise for a career role to be needed and accepted, as a result, the possession of the appropriate personal capital required for a certain career role is essential for the individual to be recognised as employable, and the process of developing these capitals is what lays the foundation of the individual’s display of their career identity during Signalling and Career Building (see Figure 1).

Existing literature has pointed out four types of personal capital that contribute to employability, namely, human, social, cultural, and psychological capital [25,35,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Human capital refers to the job-relevant knowledge and skills [61] that directly contribute to one’s performance at work [25], while social capital is the sum of social and professional networks that help exploit job opportunities and mobilise existing human capital [25,69]. Meanwhile, cultural capital is the knowledge, dispositions, and behaviours that create fitness in the working situations and increase work-related functionalities; and psychological capital means the positive psychological capability—typically, self-efficacy, optimism, resilience, and adaptability—that enables proactive and adaptive behaviours that improve job performance and personal well-being [25,35].

However, when the processual employability perspective is proposed, it does not mean to debate about what configuration of possession of the above capitals would increase employability. Instead, by utilising the career identity concept, the processual employability perspective emphasises enabling a self-directed process of acquiring the possession of these capitals in a way that is most suitable for their particular situation. Such theoretical possibility is made feasible due to the unique features of identity. Different from personal capital, career identity is not a possession of competitiveness or resources [25,35,68], but the dynamic understandings, definitions, and key schemes that a person uses to define, direct, and present themselves in work-related contexts [24,44,47,70]. The result of achieving a career identity is not (only) work-related outcomes, but, more importantly, meaningful connections with the WoW [24,71,72]. Therefore, career identity is the manifestation of one’s ontological views on themselves in the WoW, which affects one’s attitudes, emotions, beliefs, and motivations of actions when entering a new social context [44,48,56,58,73].

Since career identity is relational and socially constructed during an individual’s interactions with elements on the IWI [6,48], it is therefore developmental and fluid [74] in service of making enduring and confident choices to personally invest in enacting itself [53,57] as to bring the sense of personal continuity, direction, and certainty [41]. In other words, personal capitals are the work-related competitiveness or resources that aid workplace performance, while career identity is the manifestation of one’s ontological views about themselves in the career context, which affects their attitudes, emotions, beliefs, and motivations to invest in acquiring these capitals [44,48,56,58,73]. If we may elaborate such difference with a maybe less ideal example, personal capital may be seen as the ingredients, equipment, and staff in a restaurant kitchen, while career identity is seen as the chef who decides what a satisfying meal for the customers should look like and what, as well as how, the above resources should be organised or developed. This is why we tend to differentiate career identity from personal capital, although some researchers might argue differently [25]. By such differentiation, the processual employability discourse is made compatible with the so-called possessional employability discourse [7,13] by seeing the possession of personal capital as a result of career identity development. Hence, we call this component of processual employability Self-directed Capital Development.

This process does not only comprise learning activities in a narrow sense (such as formal education and training), because the acquisition of social, cultural, and psychological capital is deeply rooted in experiencing social interactions [48], as well as comprehending and internalising them over time [25]. This is performed through socialisation, such as observation, reflective thinking, and professional practices [73,75], and by achieving deeper personal change and stance in the form of identity work [38]. To achieve this, the premise is that the individual has a sense of responsibility in their own career so they can be agentic in making conscious decisions and actions for their growth [20]. Career identity, therefore, serves as the motivation for Self-directed Capital Development [16] by promoting the exercise of agency as an inherent part of identity work [30], as well as by providing meaning and value orientations [20,65] that initiate and internalise personal change. Indirectly, career identity also promotes a higher level of well-being through the agency [41,45] and the development of social and psychological capital [68,76]. This is also why we propose to differentiate career identity from a form of personal capital [25] so it can be seen as a core that drives and links with the development of other personal capital.

4.3. The Fletch—Career Identity Management

Like an arrow cannot stably and continuously fly without the fletch, the processual employability construct does not stand without the management of the career identity. Because career identity functions as a personal reference structure to perceive and understand the information from individual interactions and experiences in a social context [77], career identity is the key that a person will evolve in adaptive behaviours as a response to the changing social context. Therefore, the management of career identity forms the “backend” of the processual employability arrow on the behavioural level (see Figure 1). It comprises activities of knowing, exploring, and changing one’s career identity based on the experience from the “front end”. This aspect of processual employability comprises perceiving and appraising the individual’s own dispositions, values, and capabilities in relation to the context [16,30,60]. It also includes the implicit activities that measure and adjust goals so a balance between the self-perceptions of objective capabilities and the self-perceptions of subjective values, interests, aptitudes, and aspirations [7,30,60]. These activities often take the form of career-related information gathering, dialogues or guidance-seeking [7,78], intra-personal or inter-personal exploration [7], and identification of possibilities [78].

Career Identity Management enables an individual to have clarity on self-awareness to make informed decisions according to how they are positioned to the provision of opportunities of the WoW, so one’s perceived employability is enhanced [78]. By managing the career identity, one also builds clarity on values, interests, aptitudes, and aspirations [30], which contributes to the sense of “knowing why” [14,65,79]. Therefore, career identity management facilitates the achievement of self-directed, value-driven careers with psychological success and higher well-being [20,80].

Concluding the above, we describe the processual employability construct as an arrow shooting into the turbulent air of IWI, and the arrow is made of the three parts of Signalling and Career Building, Self-directed Capital Development, and Career Identity Management. Meanwhile, we comprehend these processual employability behaviours as a form of identity work that individuals use to enact, maintain, or repair their career identity [30,31] in pursuit of an achieved career identity. In essence, it is the transformation of career-related “mode of being” [81] that interacts in between these behaviours and enables their development responding to social context changes. The processual employability construct is, therefore, only complete when the underlying career identity emergence process is embedded (as shown in Figure 1). In the next section, we will discuss how the career identity emergence process acts as the interactive core in relation to the above processual employability behaviours.

5. Career Identity Emergence in Relation to Processual Employability

We have shown that career identity is both the reason for, and the result of, the processual employability behaviours facing the changing IWI. This informs our approach to explain the achieving of processual employability by examining the underlying career identity formation process and the identity work that prompts processual employability. In this section, we will first give an overview of the four career identity formation stages to show how they are placed together. Then, we will specify each stage and explain the identity work involved that links to processual employability behaviours.

Using the concept of identity work, processual employability is a result of one’s cognitive and behavioural efforts to seek, enact, or maintain a career identity that provides the direction on acting as a part of a group in a career context [30,31]. Such a process enables the individual to land in a career role where their career identity is enacted while their practices of enactment are accepted as employable, which increases individual employability [6,58]. We thus call the above process Identity Enactment in the career identity emergence process. Secondly, the experience of engaging with processual employability behaviours also causes changes in career identity, as the individual experiences conflicts between their current practices to claim a career identity and perceived social recognition, which leads to the construction of expanded, repaired, or new career identity as the individual attempts to explain or makes sense of such experience [31,51,73]. We thus call this process Identity Construction in the career identity formation process.

There are also two types of interim activities in between Identity Enaction and Identity Construction to link them together. When an individual makes efforts in Self-directed Capital Development, Signalling, and Career Building activities, they attempt to claim a career identity and seek affirmation from the social context they face [6,13]. This identity claim/affirmation process forms the lived experience of engaging with the social interactions on the IWI, which forms the foundation for informing and changing one’s career identity from their experience [32,36,71]. As the contextual components in the IWI change, such interactions would result in exigencies in which the individuals feel challenged and unconfident in enacting the current identity [49] or stuck or suffering with the current identity [47]. Such experience is caused by perceiving the social validation of their identity claim practices [6,13]. Based on the above, we claim that individuals will first validate their current career identity before entering Identity Construction. We thus call this process Identity Validation.

An interim phase also exists between Identity Construction and the next Identity Enaction. When the career identity is being constructed, individuals also explore, and possibly reconsider, their current commitments to enact a career identity [57,74]. Individuals might also examine the IWI they currently face to identify options, concrete actions, and decisions to commit to [74,82]. Only after such exploration can individuals understand what to do to enact the evolved career identity. Thus, we name this stage Identity Exploration. What is worth noting is: The evolvement of career identity is not like upgrading a computer chip by pulling out the old piece and inserting a new one. Instead, it is a continuous and gradual process with much “lingering in-between” and “looking backwards” involved [38]. Therefore, Identity Exploration is intertwined with Identity Construction until a strong enough career identity emerges and directs the next Identity Enactment (see Figure 1).

When going through the above four types of career identity changes, processual employability is delivered into reality through the three types of processual employability behaviours, which forms the arrow to chart through the changing IWI dynamics. Therefore, processual employability is, in essence, an iterative process guided by Career Identity Emergence. On that basis, we form a model to conceptualise this process in the wider picture of the WoW (Figure 1). Details of this model are then explained as follows:

5.1. Identity Enactment

In this stage, individuals take action to enact their career identity in the WoW. Taking an observer’s perspective, this is when an individual takes concrete actions to claim a career identity and actualise their commitment to the career identity [53,83]. However, from the individual’s perspective, they are following the “personal reference system” provided by their career identity [77] to make decisions that fit into the particular IWI they face. This is thus the contextualised action-taking stage to achieve situatedness in a career role of a social context that the individual is motivated and agentic to pursue. The actions in this stage are directed by the identity options identified in the previous stage of Identity Exploration—those that the individual prioritises and is committed to actualising, which is guided by an emergent career identity that corresponds to the contextual components previously encountered by the individual. Therefore, the behaviours reflect the adaptation of career identity grounded in the perception of the self-in-context [16], which makes the individuals act and look more like a part of a collective group with shared practices [31,58]. Thus, the opportunity for the emergent career identity to be affirmed by the social context is increased [6,58].

Individuals mainly conduct two types of identity work to enact a career identity. The first is Changing Self-presentation directly associated with Signalling and Career Building in the processual employability behaviours. This means that individuals attempt to change their approach to creating impressions of the self during their interactions with significant others in the social context [84]. Self-presentation may include the way of speaking and engaging with others, deciding on how to perform on social occasions, how to deploy personal capital, and subjectively, how to view and interpret the signals from others [85]. For example, during a job application process, one may change the way of explaining the motivation for pursuing employment, so the career identity they enact could be shown in a convincing way with a better chance of being affirmed. Such change can also reflect itself in the approach and attitudes when deploying personal capital in the workplace to fulfil career role-related tasks. For example, individuals could change how they handle and perform in specific work assignments or take on new responsibilities that could represent their adapted career identity. The change in self-presentation also objectively increases social connections, which results in the development of social capital.

Individuals also enact their career identity by engaging with Self-directed Learning, which is directly associated with Self-directed Capital Development. Where personal capital is perceived as insufficient to enact an adapted career identity, individuals would engage in learning activities or practices to enhance the existing or acquire new personal capitals that could help reflect and enhance the adapted career identity. A typical example is that an adapted career identity could guide the individual to participate in education or training programs to acquire knowledge and skills to fulfil the adapted career identity. The adapted career identity also enables meaning, agency, and, therefore, motivation [41,86] for the individual to engage with formal or informal learning and socialisation aiming to situate into the social context they seek to join [75,87,88]. Such endeavours eventually add to the development of social, cultural, and psychological capital.

5.2. Identity Validation

From the individual’s perspective, this is a stage in which they perceive the social signals that validate their identity claims. To have the chance of validation, career identity prompts activities to engage with Career Building and Signalling. From this angle, Career Building and Signalling activities are the behavioural results of Identity Enactment and the experiential premise of Identity Validation.

Following the previous stage, the individual’s cognitive and behavioural efforts in claiming a career identity are perceived by significant others in the social context, and the latter would respond by showing affirmation or disaffirmation of the claimed career identity [6,13]. If the claimed career identity is affirmed by the social context, it means the individual’s self-representation and personal capital have been accepted as employable by the IWI context. For example, in job-seeking activities, candidates with an affirmed career identity are admitted as employable by the recruiters, which results in objective employability. Another example could be someone who recently took on a new role to lead a team in the workplace, and when his/her practices of enacting the leader’s role are accepted by co-workers and followers, the person is more employable for being in the leadership role. In this case, an employable and relatively stable career identity is achieved, with the individual having a clear focus and commitment to their chosen career role [53], and motivation to continue the current practices [47], which marks the unification of subjective and objective employability [6]. However, the claimed career identity can also be disaffirmed by the social context and lead to boundary experiences marked by the feeling of being unconfident and challenged to enact a career identity [49]. Such experiences take the form of context-related events in which the individual struggles to perceive the appropriate level of distinctiveness (e.g., feeling undervalued or underemployed), continuity (e.g., becoming a manager from an individual contributor), or coherence (e.g., a shy person learning to master public speaking for work) [40]. These events could exist throughout the Self-directed Capital Development, Signalling and Career Building process, and prompt Career Identity Management.

Either affirming or disaffirming, such signals are likely to come in a mix from significant others in the social context to be perceived and interpreted by the individual. Therefore, Perceiving is a key identity work in this stage. The individuals open themselves to and communicate with the social context they interact with and gather information regarding how their identity claim has been perceived and interpreted by others [36]. Perceiving can be performed by observing the feedback responding to their actions of identity claim [73]. Such identity claims test their adapted career identity [73] and provide essential information on the acceptance of one’s adaptations in the Self-directed Capital Development, Signalling, and Career Building behaviours, which informs and influences the career identity [38,82]. The other type of identity work is External Dialogue, in which individuals seek to receive direct feedback on how others view their behaviours of identity claim. These dialogues help the individual realise what and how their identity claims are accepted in a social context [47,49], and where they have been positioned in the social environment as a career role [29]. On that basis, they stimulate reflections on the meaning of the individual’s actions in identity claims and add to the motivation of their career identity commitments [29,83]. Individuals might also turn to their trusted ones for counsel or feedback in terms of their identity claim behaviours [7], which also forms a type of External Dialogue, although they might not be the ones who directly grant or maintain employment opportunities.

5.3. Identity Construction

In this stage, the individuals make sense [32,52] of the information from the previous stage of Identity Validation and adapt their career self-views to explain their encounters in reality. This process represents the internal dialogue [49] as individuals struggle to negotiate an updated version of a career identity that justifies their positioning in the social context [29,44] to achieve a sense of distinctiveness, continuity, and coherence [43], clarity, and understanding about their own career [21]. These implicit activities bring fragmented pieces of information received from the previous stage into a structure, and inform one’s subjective interests, values, and aspirations as well as their objective capabilities, which aligns with the Career Identity Management of processual employability [60]. As a result, the current career identity is adapted in its structure and salience as a new personal frame of reference, while such change is bounded by the social context [38,70].

The key identity work activities include Internal Dialogue and Identity Alteration. Individuals sort the information perceived from the previous stage, give them meaning to make sense of them [32,89], and incorporate them into the social context’s viewpoints and judgements of themselves [49]. Using others as a mirror, individuals see their objective capabilities and subjective values, interests, aptitudes, and aspirations [30,60] reflected in the IWI they face [84]. Connecting things that happened with their own conduct and career identity in the form of autobiographical reasoning [54,90], individuals have Internal Dialogues with themselves to build causality between the outside world and their own behaviours, choices, feelings, and cognitions [49]. Such dialogue eventually results in the understanding of how social responses are linked to one’s identity enactment behaviours [49] as feedback for institutionalisation [32].

To achieve a balance between the enacted identity and the perceived social validation, individuals go through Identity Alteration to alter the structure of their career self-definition. It is possible that an individual could reject a career identity or stick with the current career identity [6] depending on the differences in individual dispositions and the particular IWI they face. However, we choose to use the term alteration to dilute the sense of dualism in this identity work process, since the pursuit of a sense of identity continuity and coherence [43] makes it reasonable to believe that this is not likely to be a complete refusal or persistence to the current career identity. The altered career identity is more likely to be a revised version of the previous one, with some structures newly added, some made obsolete, some condensed, and some preserved. The change is made according to what the individual evaluates as practical to solve the identity claim/affirmation conflict perceived earlier [77], which in fact builds up to a career identity that survives the experienced reality in a specific social context.

5.4. Identity Exploration

Through the previous stages, a new version of career identity which embodies the contextual adaptations and revisions has emerged. To bring the new career identity into enactment, the individual starts exploring possibilities to enact their adapted career identity. In this stage, commitment is the keyword to answer the question: “now what?”. By doing so, individuals gather information about the WoW, evaluate available choices, and make contextually informed, value-driven, and meaningful decisions on their approach to enact the new career identity [7,83], which aligns with a protean career orientation [20] that leads to employability [80].

The identity work process involved in this stage is Environmental Exploration accompanied by Commitment-making. Environmental Exploration is the activities in which individuals proactively seek opportunities where their adapted career identity can be demonstrated, and work experience can be acquired. This drives the individual to engage with Career Building, including networking, investigating the environment, gathering job-market information, and identifying opportunities, which are all significant in improving processual employability [7,35]. Through such actions, the individual paves the way for Identity Enactment, but it does not necessarily lead to the next stage: If there appear to be no opportunities ideal and available, the individual could turn to evaluate their goal and options under the adapted career identity and adjust their commitment [57,74]. Either way, individuals explore the environment to see how their adapted career identity could fit into the IWI they face to achieve the self-claimed and socially validated career identity [13]. Therefore, Environmental Exploration is closely linked with Commitment-making. Commitments are the actions and behavioural changes that individuals invest in enacting an identity [48,83]. With the information gathered from earlier, individuals identify the commitments they need to make to enact the adapted career identity, generate meaningful goals [88], and evaluate the feasibility of them in synthesis with their adapted career identity [60,82]. Career identity supports these identity work processes as the motivational factor [29,88], and as a result, career indecision could be overcome, and the person–job fit is more likely to be achieved.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This conceptual paper attempts to detail the identity-based processual employability construct to explain the source, components, and interactive nature of processual employability. This is completed by discussing the construct of processual employability, the role of career identity in processual employability, and the process of identity work beneath them. We develop a four-stage conceptual model which essentially explains processual employability as the behavioural-level representation of career identity work. With this model, we identify how career identity is the underpinning factor and compass of the processual employability [10,24], which enriches the discussions on the processual employability [6,7,13] and sustainable employability [9,18]. Based on a clarified role of career identity in enabling context-sensitive employability [16,25,29,58,91], we also specify the links between processual employability behaviours and career identity change through identity work, which demonstrates how the components of employability are not only co-existing but also inter-dependent with each other [21]. Our model responds to the call for conceptualising the core of employability and combining multiple views [27] with a holistic, identity-based theory. On a theoretical level, it reflects the interactional and dynamic nature of employability by involving career identity change in the face of transitions between changing social contexts [16,80]. In this way, we theorise employability as a social construct co-delivered by the individual and social environment they are in, which is a rather rare but highly needed perspective in the field of employability research [9], and poses a challenge to the traditional human capital-focused employability discourse [8,58] aiming to “produce” human resources.

Our model provides educators, career counsellors, and teachers with a theoretical framework to view employability as a contextualised result of career identity emergence. It suggests that if higher education means building sustainable and student-focused employability, learning should inform career identity. To illustrate with an example, instructional designers and teachers might utilise this model to evaluate whether their design of student learning experience allows their students to experience the four stages of identity change, especially allowing students to make choices and demonstrate their attainment of personal capitals (the enactment), receive feedback, and have external dialogues (the validation) [29,49,76,82], so a strong learning environment may be built to positively influence student employability by allowing professional socialisation [48,73].

Meanwhile, our model highlights the practical value of positioning career identity development at the centre of employability development to enable its context-sensitive and interactive nature [13,16]. For example, career counsellors and professionals could focus on the part of Identity Construction and Exploration, where the internal dialogical process [49] about subjective value and aptitude system is understood and clarified. Potentially, our model could be a theoretical foundation for a tool to identify the weakness in the individual’s career identity development process, which provides guidance for proper intervention to improve their level of career identity development. This would help students to build meaning in learning experiences that inform career identity [47,65,92] and further promote behavioural change and value-oriented career pursuits [20,93]. With efforts from various aspects but covering the whole process of the model, the higher educational institution could build a social eco-system that promotes employability with a focus on career identity emergence and the creation of the future workforce [8,11,94].

For future research, our discussions indicate the need to probe career identity structure as the antecedent of employability and proactive career behaviours. Future research could test the relationship between the processual employability behaviours and the identity work variables to identify the antecedents of processual employability and further specify its construct. In addition, our model shows that career identity is formed both as narratives based on autobiographical reasoning and as commitments led by environmental exploration. Future research could combine both of the above perspectives [41] to explore how a mature career identity can be constructed to benefit processual employability behaviours. Such efforts could make clear the career identity emergence process in relation to social interactions [28] and shed light on stimulating context-sensitive processual employability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., X.Z. and G.B.; Supervision, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and reviewers of the journal for their hard work evaluating and reviewing this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN 9780745639864. [Google Scholar]

- Kift, S. Employability and Higher Education: Keeping Calm in the Face of Disruptive Innovation. In The Employability Agenda; Jiggs, J., Crisp, G., Letts, W., Eds.; Education for Employability; Brill Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Trede, F.; Macklin, R.; Bridges, D. Professional Identity Development: A Review of the Higher Education Literature. Stud. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y. The Core Task of Future Education: Nurturing Mindset. J. High. Educ. 2020, 41, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ge, J. Replying to Management Challenges: Integrating Oriental and Occidental Wisdom by HeXie Management Theory. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2012, 6, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, L. Becoming a Graduate: The Warranting of an Emergent Identity. Educ. Train. 2015, 57, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay-Somerville, B.; Scholarios, D. Position, Possession or Process? Understanding Objective and Subjective Employability during University-to-Work Transitions. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1275–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, G.; Higgs, J.; Letts, W. The Employability Agenda. In Learning for Future Possibilities; Higgs, J., Letts, W., Crisp, G., Eds.; Education for Employability; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fleuren, B.P.I.; de Grip, A.; Jansen, N.W.H.; Kant, I.; Zijlstra, F.R.H. Unshrouding the Sphere from the Clouds: Towards a Comprehensive Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Employability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgstock, R.; Jackson, D. Strategic Institutional Approaches to Graduate Employability: Navigating Meanings, Measurements and What Really Matters. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2019, 41, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, J.; Cloutman, J. Employability Interests and Horizons: Public and Personal Realisations. In The Employability Agenda; Jiggs, J., Crisp, G., Letts, W., Eds.; Education for Employability; Brill Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- McCash, P. Employability and Depth Psychology. In Graduate Employability in Context; Tomlinson, M., Holmes, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2017; pp. 151–170. ISBN 9781137571670. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, L. Competing Perspectives on Graduate Employability: Possession, Position or Process? Stud. High Educ. 2013, 38, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouwel, S.J.C.; van Luijn, A.; Zweekhorst, M.B.M. Developing a Processual Employability Model to Provide Education for Career Self-Management. Educ. Train. 2019, 62, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, W. Pursuing Employability: A Journey More Than a Destination. In Learning for Future Possibilities; Higgs, J., Letts, W., Crisp, G., Eds.; Education for Employability; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- McIlveen, P. Defining Employability for the New Era of Work: A Submission to The Senate Select Committee on the Future of Work and Workers; The Senate: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Reid, J. Redefining “Employability” as Something to Be Achieved: Utilising Tronto’s Conceptual Framework of Care to Refocus the Debate. High. Educ. Ski. Work. Based Learn. 2016, 6, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Klink, J.J.; Bültmann, U.; Burdorf, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Zijlstra, F.R.; Abma, F.I.; Brouwer, S.; van der Wilt, G.J. Sustainable Employability—Definition, Conceptualization, and Implications: A Perspective Based on the Capability Approach. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2016, 42, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, P.M.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Van Vuuren, T. “I WILL SURVIVE” A Construct Validation Study on the Measurement of Sustainable Employability Using Different Age Conceptualizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T.; Yip, J.; Doiron, K. Protean Careers at Work: Self-Direction and Values Orientation in Psychological Success. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D.E.; Liu, M.; Maria Van der Heijden, B.I.J. Work in Progress: The Progression of Competence-Based Employability. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, P.A.; Keating, L.A.; Ashford, S.J. How Being in Learning Mode May Enable a Sustainable Career across the Lifespan. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrier, A.; Sels, L. The Concept Employability: A Complex Mosaic. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2003, 3, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J.; Ashforth, B.E. Employability: A Psycho-Social Construct, Its Dimensions, and Applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Forms of Graduate Capital and Their Relationship to Graduate Employability. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J. A Dispositional Approach to Employability: Development of a Measure and Test of Implications for Employee Reactions to Organizational Change. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2008, 81, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbert, L.; Bernaud, J.-L.; Gouvernet, B.; Rossier, J. Employability: Review and Research Prospects. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2016, 16, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A. Professional Identity: A Concept Analysis. Nurs. Forum 2020, 55, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, F.; Lengelle, R.; Winters, A.; Kuijpers, M. A Dialogue Worth Having: Vocational Competence, Career Identity and a Learning Environment for Twenty-First Century Success at Work. In Enhancing Teaching and Learning in the Dutch Vocational Education System; de Bruijn, E., Billett, S., Onstenk, J., Eds.; Professional and Practice-Based Learning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 18, pp. 139–155. ISBN 9783319507323. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. Who Am I and What Am I Going to Do with My Life? Personal and Collective Identities as Motivators of Action. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 44, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H.; Petriglieri, J.L. Identity Work and Play. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2010, 23, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; Foundations for Organizational Science; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-8039-7176-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fugate, M.; van der Heijden, B.; De Vos, A.; Forrier, A.; De Cuyper, N. Is What’s Past Prologue? A Review and Agenda for Contemporary Employability Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2021, 15, 266–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, W.; McMahon, M. Career Development and Systems Theory: Connecting Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Career Development Series; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 9789462096356. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.; Dodd, L.J.; Steele, C.; Randall, R. A Systematic Review of Current Understandings of Employability. J. Educ. Work 2015, 29, 877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgstock, R.; Grant-Iramu, M.; Bilsland, C. Going beyond “Getting a Job”: Graduates’ Narratives and Lived Experiences of Employability and Their Career Development. In Learning for Future Possibilities; Higgs, J., Letts, W., Crisp, G., Eds.; Education for Employability; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yorke, M. Employability in Higher Education: What It Is, What It Is Not; Learning and Employability Series; The Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, H. Working Identity: Unconventional Strategies for Reinventing Your Career; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2003; p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Glavin, K.W.; Haag, R.A.; Forbes, L.K. Fostering Career Adaptability and Resilience and Promoting Employability Using Life Design Counseling. In Psychology of Career Adaptability, Employability and Resilience; Maree, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 433–445. ISBN 9783319669533. [Google Scholar]

- van Doeselaar, L.; Becht, A.I.; Klimstra, T.A.; Meeus, W.H.J. A Review and Integration of Three Key Components of Identity Development: Distinctiveness, Coherence, and Continuity. Eur. Psychol. 2018, 23, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doeselaar, L.; McLean, K.C.; Meeus, W.; Denissen, J.J.A.; Klimstra, T.A. Adolescents’ Identity Formation: Linking the Narrative and the Dual-Cycle Approach. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Life Design: A Paradigm for Career Intervention in the 21st Century. J. Couns. Dev. 2012, 90, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K.C.; Syed, M.; Pasupathi, M.; Adler, J.M.; Dunlop, W.L.; Drustrup, D.; Fivush, R.; Graci, M.E.; Lilgendahl, J.P.; Lodi-Smith, J.; et al. The Empirical Structure of Narrative Identity: The Initial Big Three. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Process. Individ. Differ. 2020, 119, 920–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPointe, K. Narrating Career, Positioning Identity: Career Identity as a Narrative Practice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.M.; Lodi-Smith, J.; Philippe, F.L.; Houle, I. The Incremental Validity of Narrative Identity in Predicting Wellbeing: A Review of the Field and Recommendations for the Future. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 20, 142–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T.; Chandler, D.E. Psychological Success: When the Career Is a Calling. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, F. The Development of a Career Identity. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 1998, 20, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M.; Jackson, D. Professional Identity Formation in Contemporary Higher Education Students. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, F.; Lengelle, R. Narratives at Work: The Development of Career Identity. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2012, 40, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Constructing Careers: Actor, Agent, and Author. J. Employ. Couns. 2011, 48, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. Career Counseling, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781433829550. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy-Spicer, D.H. Where the Action Is: Enactment as the First Movement of Sensemaking. In Educational Leadership, Organizational Learning, and the Ideas of Karl Weick; Johnson, B., Jr., Kruse, S.D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 25. ISBN 9781315114095. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, J.; Marcia, J.E. The Identity Statuses: Origins, Meanings, and Interpretations. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 31–53. ISBN 9781441979872. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.P. The Psychology of Life Stories. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, J.L. Identity, Development and Desire: Critical Questions. In Identity Trouble; Caldas-Coulthard, C.R., Iedema, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2008; pp. 17–42. ISBN 9781349522736. [Google Scholar]

- Slay, H.S.; Smith, D.A. Professional Identity Construction: Using Narrative to Understand the Negotiation of Professional and Stigmatized Cultural Identities. Hum. Relat. 2011, 64, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E. Identity Formation in Adolescence: The Dynamic of Forming and Consolidating Identity Commitments. Child Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. Re-Conceptualising Graduate Employability: The Importance of Pre-Professional Identity. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Lees, R. Marketing Education and the Employability Challenge. J. Strateg. Mark. 2016, 25, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgstock, R. The Graduate Attributes We’ve Overlooked: Enhancing Graduate Employability through Career Management Skills. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2009, 28, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, E.; Nelissen, J.; De Cuyper, N.; Forrier, A.; Verbruggen, M.; De Witte, H. Employability Capital: A Conceptual Framework Tested Through Expert Analysis. J. Career Dev. 2019, 46, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Çavuş, M.; Gökçen, A. Psychological Capital: Definition, Components and Effects. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 5, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M. Rethinking Graduate Employability: The Role of Capital, Individual Attributes and Context. Stud. High Educ. 2017, 43, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFillippi, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The Boundaryless Career: A Competency-Based Perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital and Beyond; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; ISBN 9780199316472. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, H.; Rastogi, R. Psychological Capital and Career Commitment: The Mediating Effect of Subjective Wellbeing. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yu, F.; Li, T. Career Capital and Wellbeing: A Configurational Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helens-Hart, R. The Employability Self-Assessment: Identifying and Appraising Career Identity, Personal Adaptability, and Social and Human Capital. Manag. Teach. Rev. 2019, 4, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, E.P.; Rich, Y. Identity Education: A Conceptual Framework for Educational Researchers and Practitioners. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 46, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, S. Adolescent Identity Development in Context. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, M.; Wåhlin, N. Identity Construction among Boundary-Crossing Individuals. Scand. J. Manag. 2001, 17, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker Caza, B.; Creary, S. The Construction of Professional Identity. In Perspectives on Contemporary Professional Work; Wilkinson, A., Hislop, D., Coupland, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 259–285. ISBN 9781783475575. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, S.S.; Ghayas, S. Process of Career Identity Formation among Adolescents: Components and Factors. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T. Careers and Socialization. J. Manag. 1987, 13, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengelle, R.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Meijers, F. The Foundations of Career Resilience. In Psychology of Career Adaptability, Employability and Resilience; Maree, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 29–47. ISBN 9783319669533. [Google Scholar]

- Berzonsky, M.D. A Social-Cognitive Perspective on Identity Construction. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 55–76. ISBN 9781441979872. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.; Wilton, N. Perceived Employability among Undergraduates and the Importance of Career Self-Management, Work Experience and Individual Characteristics. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.B.; Claman, P.H.; DeFillippi, R.J. Intelligent Enterprise, Intelligent Careers. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1995, 9, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellazzo, L.; Bonesso, S.; Gerli, F.; Batista-Foguet, J.M. Protean Career Orientation: Behavioral Antecedents and Employability Outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. Graduate Employability: A Review of Conceptual and Empirical Themes. High Educ. Policy 2012, 25, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaslin, M. Co-Regulation of Student Motivation and Emergent Identity. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 44, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, K.; Schwartz, S.J.; Goossens, L.; Pollock, S. Employment, Sense of Coherence, and Identity Formation: Contextual and Psychological Processes on the Pathway to Sense of Adulthood. J. Adolesc. Res. 2008, 23, 566–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D. The Self; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 9780805861563. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education. Rev. Res. Educ. 2000, 25, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Toward a Psychology of Human Agency: Pathways and Reflections. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. Motivation and Social Cognitive Theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen, S.B. A Situative Turn in the Conversation on Motivation Theories. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann Glynn, M.; Watkiss, L. Of Organizing and Sensemaking: From Action to Meaning and Back Again in a Half-Century of Weick’s Theorizing. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 1331–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, T.; Reese, E. Getting a Life Takes Time: The Development of the Life Story in Adolescence, Its Precursors and Consequences. Hum. Dev. 2015, 58, 172–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.A.; Inman, M.; Rojas, H.; Williams, K. Transitioning Student Identity and Sense of Place: Future Possibilities for Assessment and Development of Student Employability Skills. Stud. High Educ. 2018, 43, 891–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. Business Graduate Employability—Where Are We Going Wrong? High Educ. Res. Dev. 2013, 32, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Li, C. Research-Led Learning and Critical Thinking; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2021; ISBN 9787521325638. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Bell, K.; Bennett, D.; McAlpine, A. Employability in a Global Context: Evolving Policy and Practice in Employability, Work Integrated Learning, and Career Development Learning; Graduate Careers Australia: Wollongong, Australia, 2018; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).