Optimizing Health Professions Education through a Better Understanding of “School-Supported Clinical Learning”: A Conceptual Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Learning in Clinical Practice: Indispensable but Intangible?

3. Opportunities and Threats in School-Supported Clinical Learning

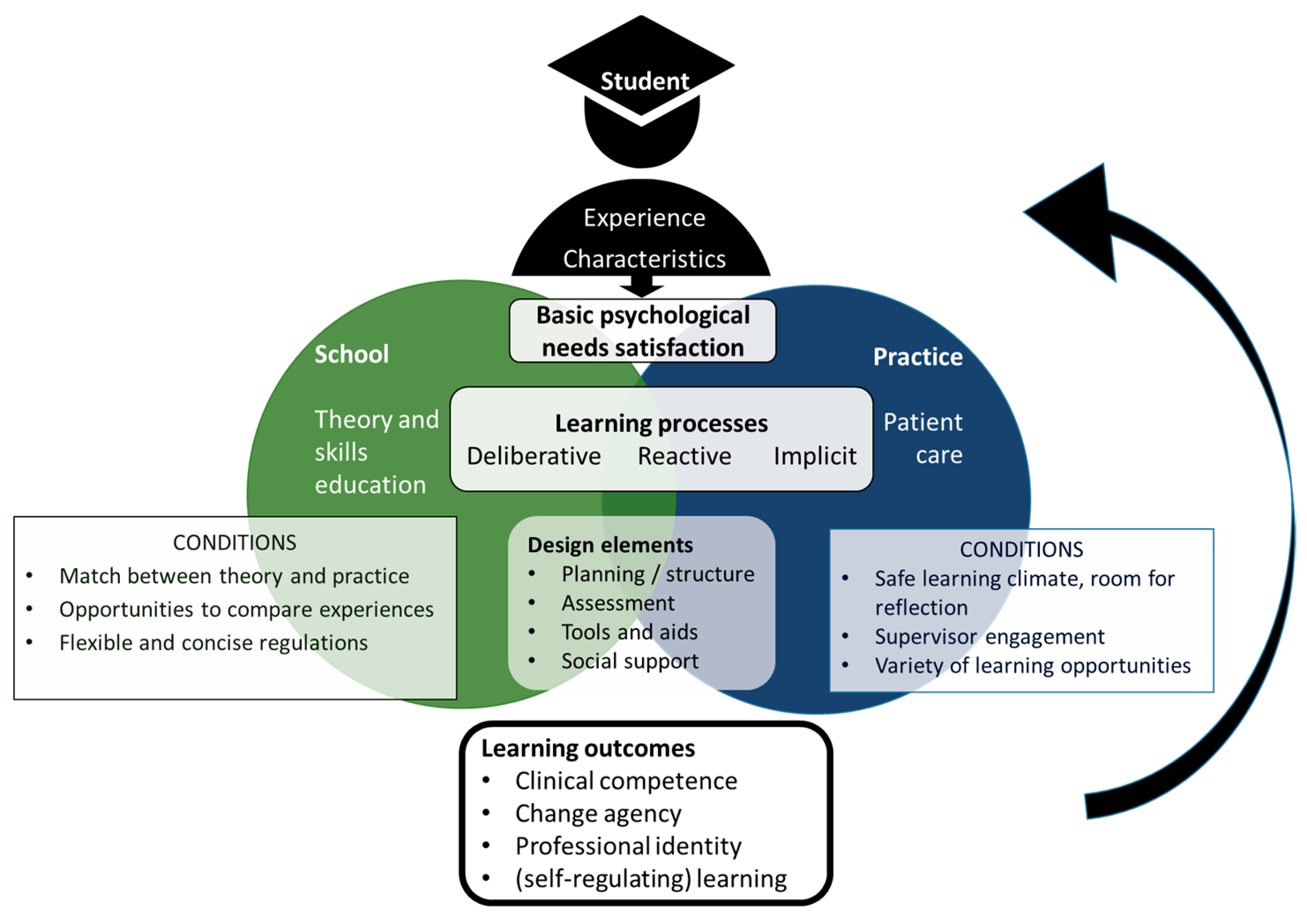

4. Description of a Conceptual Model to Study and Optimize School-Supported Clinical Learning

5. Use of the Conceptual Model in Practice and Research: General Guidelines and an Example

6. Critical Discussion of the Model and Directions for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peters, S.; Clarebout, G.; Diemers, A.; Delvaux, N.; Verburgh, A.; Aertgeerts, B.; Roex, A. Enhancing the connection between the classroom and the clinical workplace: A systematic review. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2017, 6, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcke, A.M.; Dornan, T.; Eika, B. Outcome (competency) based education: An exploration of its origins, theoretical basis, and empirical evidence. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2013, 18, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndtsson, I.; Dahlborg, E.; Pennbrant, S. Work-integrated learning as a pedagogical tool to integrate theory and practice in nursing education—An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 42, 102685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, J.; Roberts, R.; Kitto, S.; Strand, P.; Johnston, P. Using paradox theory to understand responses to tensions between service and training in general surgery. Med. Educ. 2018, 52, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.; Clarebout, G.; Van Nuland, M.; Aertgeerts, B.; Roex, A. How to connect classroom and workplace learning. Clin. Teach. 2017, 14, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Loon, K.A.; Scheele, F. Improving graduate medical education through faculty empowerment instead of detailed guidelines. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, M.; van der Burgt, S.M.E.; Bronkhorst, L.H.; Daelmans, H.E.M.; Peerdeman, S.M.; Kusurkar, R.A. Learning in and across communities of practice: Health professions education students’ learning from boundary crossing. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2022, 27, 1423–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, M.; Broeksma, L.A.; Barry, M.; Van der Burgt, S.E.M.; Daelmans, H.E.M.; Peerdeman, S.M.; Kusurkar, R.A. Bridging between school and practice? Challenges to boundary objects in nursing education. Submitted.

- Stoffels, M.; van der Burgt, S.M.; Stenfors, T.; Daelmans, H.E.; Peerdeman, S.M.; Kusurkar, R.A. Conceptions of clinical learning among stakeholders involved in undergraduate nursing education: A phenomenographic study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C. Work-based learning. In Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory, and Practice; Wiley-Blackwell and ASME: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrowolska, B.; McGonagle, I.; Jackson, C.; Kane, R.; Cabrera, E.; Cooney-Miner, D.; Di Cara, V.; Pajnkihar, M.; Prlić, N.; Sigurdardottir, A.K.; et al. Clinical practice models in nursing education: Implication for students’ mobility. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruess, R.L.; Cruess, S.R.; Steinert, Y. Medicine as a Community of Practice: Implications for Medical Education. Acad. Med. 2018, 93, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppen, L.; Irby, D.M.; Durning, S.J.; Maggio, L.A. Interventions designed to improve the learning environment in the health professions: A scoping review. MedEdPublish 2018, 7, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman-Barger, K.; Boatright, D.; Gonzalez-Colaso, R.; Orozco, R.; Latimore, D. Seeking Inclusion Excellence: Understanding Racial Microaggressions as Experienced by Underrepresented Medical and Nursing Students. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, M.; de Bourmont, S.; Paul-Emile, K.; Pfeffinger, A.; McMullen, A.; Critchfield, J.M.; Fernandez, A. Physician and Trainee Experiences with Patient Bias. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Cate, O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 1176–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramley, A.L.; McKenna, L. Entrustable professional activities in entry-level health professional education: A scoping review. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 1011–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kua, J.; Lim, W.S.; Teo, W.; Edwards, R.A. A scoping review of adaptive expertise in education. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruppen, L.D.; Irby, D.M.; Durning, S.J.; Maggio, L.A. Conceptualizing Learning Environments in the Health Professions. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.J. Kolb, integration and the messiness of workplace learning. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2017, 6, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bvumbwe, T. Enhancing nursing education via academic-clinical partnership: An integrative review. Int J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 3, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, Y.; Mann, K.V. Faculty development: Principles and practices. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2006, 33, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gulden, R.; Timmerman, A.; Muris, J.W.M.; Thoonen, B.P.A.; Heeneman, S.; Scherpbier-de Haan, N.D. How does portfolio use affect self-regulated learning in clinical workplace learning: What works, for whom, and in what contexts? Perspect. Med. Educ. 2022, 11, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, D.G.; Ferguson, K.J. The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96. Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, D.P.; Wesevich, A.; Lichtenfeld, J.; Artino, A.R., Jr.; Brydges, R.; Varpio, L. Tying knots: An activity theory analysis of student learning goals in clinical education. Med. Educ. 2017, 51, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, K.M.; Gruppen, L.D. Competency-Based Education as Curriculum and Assessment for Integrative Learning. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, M.; Peerdeman, S.M.; Daelmans, H.E.; Ket, J.C.; Kusurkar, R.A. How do undergraduate nursing students learn in the hospital setting? A scoping review of conceptualisations, operationalisations and learning activities. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flott, E.A.; Linden, L. The clinical learning environment in nursing education: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, K.; Titchen, A.; Hardy, S. Work-based learning in the context of contemporary health care education and practice: A concept analysis. Pract. Dev. Health Care 2009, 8, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordquist, J.; Hall, J.; Caverzagie, K.; Snell, L.; Chan, M.-K.; Thoma, B.; Razack, S.; Philibert, I. The clinical learning environment. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, S.F.; Bakker, A. Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 132–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y.; Sannino, A. Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Cate, T.J.; Kusurkar, R.A.; Williams, G.C. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE guide No. 59. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, M.; Koster, A.S.; van der Burgt, S.M.E.; de Bruin, A.B.H.; Daelmans, H.E.M.; Peerdeman, S.M.; Kusurkar, R.A. The role of basic psychological needs satisfaction in the relationships between learning climate, self-regulated learning and learning outcomes in the clinical setting. Submitted.

- Hodson, N. Landscapes of practice in medical education. Med. Educ. 2020, 54, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.J.H.; Kulasegaram, K.M. Beyond the tensions within transfer theories: Implications for adaptive expertise in the health professions. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2022, 27, 1293–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eames, C.; Coll, R.K. Cooperative education: Integrating classroom and workplace learning. In Learning through Practice; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 180–196. [Google Scholar]

- Eraut, M. Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 70, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynjälä, P.; Beausaert, S.; Zitter, I.; Kyndt, E. Connectivity between education and work: Theoretical models and insights. In Developing Connectivity between Education and Work; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bouw, E.; Zitter, I.; de Bruijn, E. Characteristics of learning environments at the boundary between school and work–A literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskelä, P.; Nykänen, S.; Tynjälä, P. Models for the development of generic skills in Finnish higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2018, 42, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, C.; Evans, P.; Jerez, O. How to encourage intrinsic motivation in the clinical teaching environment?: A systematic review from the self-determination theory. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2015, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.S.; Rafique, J.; Vincent, T.R.; Fairclough, J.; Packer, M.H.; Vincent, R.; Haq, I. Mobile Medical Education (MoMEd)-how mobile information resources contribute to learning for undergraduate clinical students-a mixed methods study. BMC Med. Educ. 2012, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogossian, F.E.; Cant, R.P.; Ballard, E.L.; Cooper, S.J.; Levett-Jones, T.L.; McKenna, L.G.; Ng, L.C.; Seaton, P.C. Locating “gold standard” evidence for simulation as a substitute for clinical practice in prelicensure health professional education: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 3759–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paci, M.; Faedda, G.; Ugolini, A.; Pellicciari, L. Barriers to evidence-based practice implementation in physiotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2021, 33, mzab093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramis, M.-A.; Chang, A.; Conway, A.; Lim, D.; Munday, J.; Nissen, L. Theory-based strategies for teaching evidence-based practice to undergraduate health students: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konkola, R.; Tuomi-Gröhn, T.; Lambert, P.; Ludvigsen, S. Promoting learning and transfer between school and workplace. J. Educ. Work. 2007, 20, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, S.; Lenouvel, E.; Cantisani, A.; Klöppel, S.; Strik, W.; Huwendiek, S.; Nissen, C. Working with entrustable professional activities in clinical education in undergraduate medical education: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masso, M.; Sim, J.; Halcomb, E.; Thompson, C. Practice readiness of new graduate nurses and factors influencing practice readiness: A scoping review of reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 129, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lave, J. Situating learning in communities of practice. Perspect. Soc. Shar. Cogn. 1991, 2, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoffels, M.; Peerdeman, S.M.; Daelmans, H.E.M.; van der Burgt, S.M.E.; Kusurkar, R.A. Optimizing Health Professions Education through a Better Understanding of “School-Supported Clinical Learning”: A Conceptual Model. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060595

Stoffels M, Peerdeman SM, Daelmans HEM, van der Burgt SME, Kusurkar RA. Optimizing Health Professions Education through a Better Understanding of “School-Supported Clinical Learning”: A Conceptual Model. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(6):595. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060595

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoffels, Malou, Saskia M. Peerdeman, Hester E. M. Daelmans, Stephanie M. E. van der Burgt, and Rashmi A. Kusurkar. 2023. "Optimizing Health Professions Education through a Better Understanding of “School-Supported Clinical Learning”: A Conceptual Model" Education Sciences 13, no. 6: 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060595

APA StyleStoffels, M., Peerdeman, S. M., Daelmans, H. E. M., van der Burgt, S. M. E., & Kusurkar, R. A. (2023). Optimizing Health Professions Education through a Better Understanding of “School-Supported Clinical Learning”: A Conceptual Model. Education Sciences, 13(6), 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060595