Abstract

Home education is a phenomenon that has been increasing globally over the past decade, particularly for families of children with special educational needs or disabilities. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this phenomenon with many families continuing to home educate even after their children can officially return to school. This paper reports on a small-scale design-based research project that explored the needs of families who are home educating children with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). Working in partnership with educational settings, practitioners, and families during the second year of the pandemic, academic researchers in Malaysia and England designed, implemented and evaluated a home learning pack for children with ASD aged 6–12 years old. The findings emphasised the role of economic, social and cultural capital for the families involved and how this impacted their ability to work and educate their children successfully. This raises crucial questions in relation to the place of home education within the wider international inclusive education debate and matters of social equality whilst also highlighting key questions for future research in this field on how policy and provision might develop to meet a growing diversity of need.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a notable increase in families with children with special education needs and disabilities (SEND) choosing to educate at home [1,2]. Over the past 5 years in the UK, this increase has been as much as 57%, with a further 1000 children waiting for a place in schools [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated this phenomenon with national lockdowns in many countries forcing school closures and shifting the role of educator from teacher to parent [3]. This project developed in response to this trend and the international pandemic practice of home education to evaluate how families with children with ASD effectively educate and to consider how inclusive education policy might respond to these developments.

As four academic researchers (two from Malaysia and two from England), we adopted a design-based approach to research in collaboration with 14 practitioners and 11 parents from three educational settings. We began the research with a baseline study to explore the needs for supporting home education for children with ASD. This then enabled us to design and trial a pack of home learning resources with six families before evaluating its use and impact. We conducted this research with a critical eye to the international meaning and practices of ’Inclusive Education’. The education tools, data and meanings that emerged cast light on commonly shared international realities for families living and educating with disability. Furthermore, the collaboration between researchers, practitioners and families highlighted meaningful and impactful ways society and its institutions could work if they aim to be responsive and inclusive of its membership whilst also raising questions as to what families and practitioners currently understand by ‘equal’ or ‘inclusive’ education.

This paper is presented in two parts. The first considers inclusive education in the context of home learning. We follow with a brief overview of Bourdieu’s thinking tools as concepts to explore how the system of education positions learning for children with SEND. This leads us to reflect on how the domains of learning, rather than core curriculum content, value individual children by providing a structure for learning both at home and in school. The second part sets out the present study and our research findings, which reimagine inclusive pedagogical practices for whole child development and academic progression.

2. Inclusive Education and the Question of Home Learning—International Developments

Evidence on a global scale highlights the negative impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had upon children’s learning and their expected chronological levels of attainment and progression [4,5]. For children with SEND, the picture is not as clear, with some research reporting that the lockdown has improved cognition and language skills for children with ASD but that social and emotional skills have worsened (Huang et al., 2021). The support for families of children with ASD during lockdowns in both England and Malaysia has varied depending on the education setting their child attended and the services they were accessing, as well as locality and cultural issues [6]. Consequently, the education tools and resources needed at home have also varied—both during and after school closures. These matters have all contributed to international concerns regarding the changing place and impact of inclusive education upon learners.

When questioning what is ‘Inclusive Education’ and how the diversity of learner needs has been met in England and Malaysia, one discovers a variety of positions, perspectives, policies and practices, which claim to be ‘Inclusive Education’ [7]. As a discourse, inclusive education emerged from the international disability rights movement and other related equality movements in the 1980s and 1990s, e.g., the rights of the child (UN 1989). Where there were barriers preventing the integration of children with disabilities, the ideals and policies of inclusion demanded these be challenged.

The theory and philosophy behind inclusive education is clearly depicted in the work of the Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education [8] and the academic research of Allan [9], Barnes [10] and Barton [11]. These sources, and their engagement with inclusive education, place its emphasis and practice with that of human rights and equality. Individuals are not equal; they bring with them a certain habitus and capital to the field of education that afford (or do not afford) their access to opportunities for learning [12]. An effective and inclusive pedagogy might be located within a specific location such as a school building or elsewhere. Most importantly, it should take place in an education space that values all aspects or domains of learning, understands and embraces diversity, and considers the needs of all learners and their families—whether that be in school, alternative provision or at home.

2.1. Key Domains of Learning in Special Education

When children with SEND are educated within mainstream schooling, they are expected to fit into a system of education that develops chronologically and is designed to cover academic core curriculum content. A principal concern of such an educational system is how it may contribute towards social injustice by limiting access to a suitable education via inequalities in experiences and outcome opportunities [13]. Such a system can position children with SEND at a deficit and keep them from meeting expected learning outcomes. It may not value children’s capabilities and is therefore not inclusive of children who have needs that sit outside of the curriculum, where small developmental steps need to be supported and celebrated. In the UK, these broad areas of need (key domains of learning) are set out in the SEND Code of Practice [14] as follows: ‘communication and interaction, cognition and learning, social, emotional and mental health, and sensory and/or physical needs’. These domains are explored in Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Domains of learning.

Inclusive education for children with SEND positions children as capable in their own right. It is a philosophy that aims to transform education, to value individual children and to meet their educational needs [24]. By empowering families and children with SEND to direct their own learning needs within the domains of learning rather than a core national curriculum, attitudes to learning can shift to prioritise the child rather than the system.

2.2. A Need to Support Home Education for Children with SENDs

As noted above, England and Malaysia witnessed significant challenges to special education provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. The shifting trends and practices in policy and national provision during this time resulted in children receiving most of their education at home. When a child’s learning is entirely dependent on their family’s economic, cultural and social capital, inconsistencies in family educational tools/resource provision, learner experiences and progression can be seen. Enforced home learning was found to be both beneficial and detrimental for pupils and their families with some students making gains in their learning whilst others fell further behind their peers [5].

Access to online learning resources was hindered globally for many due to poor infrastructure, access to computers and poor digital skills in homes and societies [25]. This in turn added to the emotional and psychological challenges faced by many children with SEND and their families. Bellomo et al. [6] identified children with ASD as being particularly vulnerable to the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic with increased anxiety due to a loss of routine and a lack of access to support for both the child and the family. Similarly, Amorium et al. [26] recognised the importance of maintaining routines, and for those families that were able to implement a clear structure to learning at home. the benefits could be seen in terms of reduced anxiety and improved focus.

It becomes clear that the impact of learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic meant inconsistency in provision, family experience and progression for many children [27]. Despite a family’s desire to support the educational needs of their child(ren), capital, working commitments and hectic work routines presented as regular barriers [28]. One of the key challenges to proponents of special education was the separation of learners from one another, the loss of socialisation and the reduction in family support networks [29,30]. Calls and questions raised by families of children with SEND during lockdowns/school closures included the following: How can we, as the educators at home, work towards meeting our children’s learning needs? How do we continue to ensure their effective progress and success? What tools can our school communities develop and provide for us at this time [4,6]? The authors’ methodology and the home learning provision created was in response to these calls and to the inconsistency of provision that families were receiving. Thus, our study aimed to investigate the needs of families who were home educating children with ASD by asking the following key questions:

- How can families with children with ASD be supported in home learning as part of a philosophy of inclusive education?

- What are the experiences and realities of education at home for families with children with ASD?

- How might inclusive education policies and provisions respond to these developments?

3. The Study

The nature of this project meant that practical research methods were needed in order to gain insights into parents’ needs and experiences in supporting their child’s learning at home whilst also facilitating a theory-driven design for a home learning resource [31]. Working within the tight constraints of a pandemic meant that a practical method of data collection was needed that would support the development of a home learning resource and its evaluation. Such an approach is referred to by Morgan [32] as one of pragmatism, a model of inquiry linked to John Dewey with an emphasis on human experience.

The design of such a home learning pack also needed to minimise pressure on parents for structuring learning activities while providing the capacity for discovery and independence for both parents and children in order to fulfil needs. We were keen to adopt a methodology that would appreciate the authentic everyday experience of parents supporting learning at home for their child [33,34], and this was facilitated via a pragmatic, participant-orientated approach that provided a richness of data from the participant’s perspective known as design-based research (DBR). The combination of pragmatism and DBR created a result that was so much more than a simple process of product development; instead, it was theory-driven and responsive to the ‘emergent features’ of the situation in which we were operating [31].

DBR demands a cyclical approach to product development in recognition that one cycle is not sufficient to facilitate a finished product. The process is iterative starting with an initial needs analysis that leads to the design of a product, followed by further analysis and redesign, and, as such, it ‘has many cycles, trials and improvements over time’ [35]. This paper therefore represents the first cycle of our research, the pilot project, which forms a basis for developing home learning as part of the evolving philosophy and practice of inclusive education [36].

3.1. Approach

At the needs analysis phase of the study, we conducted a baseline evaluation to gain insight into the barriers and enablers for home learning, the areas of learning with which families needed support and the resources available. Questionnaires consisted of four close-ended and six open-ended questions hosted via an online platform, and the link was distributed by email to the settings in their role as gatekeeper [37] and cascaded to staff and parents. As part of our inclusive education ethos, we wanted to be responsive to individual needs whilst empowering diversity. As such, the matter of cultural capital [38] for our families was a key element of consideration in both the design, content and accessibility of our home learning pack. We recognised the tension between the individuals and the system of education and the challenges that home learning presented to inclusive education both in theory and application.

Following the initial analysis of needs, we then developed a pilot home learning pack, which included a range of activities across all four broad areas of need, and this was shared digitally via an online platform and pdf files. Following our initial roll-out of the home learning pack, the researchers carried out an evaluation via an online questionnaire recognising the need for ease of access across two countries, time zones, cultures and a range of settings. This post-design evaluation consisted of thirteen questions, which focused on the parents’ perceptions of the format of the home learning packs in supporting their child’s learning. Our focus here was on the appropriateness of the design; how well the activities supported the child’s learning, enhanced parental knowledge, improved their confidence; and how the experience empowered both the parents and the children. Two open-ended questions focused on the barriers and limitations of using the home learning packs.

For the baseline survey, a total of twenty-five completed responses were received from 14 setting staff and 11 parents. They came from one SEND centre in England and two centres in Malaysia. Of these, eleven families from both countries agreed to take part in the next stage of the research and access the pilot home learning pack. However, only six Malaysian parents completed the final evaluation stage of the research. This may be related to a second pandemic lockdown in England at the time and the approaching end of term.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse closed questions in both the baseline and evaluation questionnaires, thus summarising the data in a meaningful way [39]. A thematic analysis [40] then facilitated the identification of patterns across the data set with systematic rigour that brought trustworthiness and credibility to the research.

3.2. Ethics

Whilst children with ASD took part in the activities, the data for this project was collected from the parents and practitioners. We recognise that a criticism of this research is a potential lack of authenticity [41] without the voices of the children being included, but time pressures and the pandemic context made this challenging. It was anticipated that, as a first cycle, of research the parents’ voices would provide some insight into the family’s experiences and that future cycles would include the children more as active participants within the research process.

Procedural ethics ensured that informed consent was obtained from the parents and practitioners involved in the study. The participants were made aware of the purposes of the project, how their data would be stored, their right to withdraw and their rights to anonymity in accordance with BERA [42] ethical guidelines.

4. Research Findings

4.1. Needs Analysis Phase

Key themes within the baseline study focused on the needs for inclusive education, the areas of learning that families with children with ASD needed support with and the design of a home learning support pack. This provided a focus for us to develop the home learning pack and the subsequent evaluation.

Findings at this initial stage indicated that parents received a good level of support from the settings (8/11 parents). When evaluated in terms of the different domains of learning, the area that was rated the lowest was sensory needs (7/11 parents). General wellbeing was the highest with all parents rating support as good or exceptional, whilst the other learning areas were held in high regard by 8–10 parents. This means that any additional home learning support should not replace setting support but should complement the learning opportunities already provided with a focus primarily on sensory needs.

When asked to elaborate on their responses, the participants indicated a need for wider support for children across the areas of social development (behaviour and independence), communication and language, cognition, and sensory skills, and this is in line with the four domains of learning as set out in the UK SEND Code of Practice [14]. Parents also reflected on their own need for support as educators for their child in terms of how to engage with their child’s learning, and this is emphasised by Parent 4, who stated, ‘I wish there is a platform for parent to seek help and the correct method to teach our kids’.

In terms of design, participants highlighted a wish for hands on practical activities that would reinforce or complement their learning in school, stating a desire for ‘ideas for home-base physical activity and hands on technology/equipment for practical learning on top of theory’ (Parent 1). They identified an interest in specific ‘sensory or fidgeting tools that are suitable for home base study’ (Parent 1), to improve motor control and concentration [43], and to have access to resources such as downloadable worksheets and useful websites. Of interest were the concerns raised by participants in terms of ‘time, training and knowledge’ (Practitioner 6) or, as Bourdieu [38] would describe, their economic, social and cultural capital. Worries about the cost of a home learning resource were highlighted, along with accessibility, in terms of the format, degree of difficulty, clarity and sustainability of parent training and empowerment.

Overall, this needs analysis highlighted a need for a home learning resource that would accomplish the following:

- Complement any existing education provision;

- Include home learning activities that cover all four domains of learning;

- Be low cost;

- Be easily accessible in terms of format and content;

- Empower parents to support their child’s learning.

These criteria thus provided an ‘orientation point for the design and re-design of home learning activities’ [44] that would take place over several cycles of DBR, providing a focus for evaluating the design and planning for the next cycle of research.

4.2. Development and Implementation Phase

During this first cycle of DBR, our hypothesis was that all children are curious and capable in their own right and that any approach to support home learning should value the child as an individual in order to meet their educational needs [24,45]. Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns and school closures shifted the role of educator from teacher to parent, inclusive education positions learning and education as a concern for all and not something that only takes place within the confines of a school building. The design, development and implementation of a home learning resource pack therefore needed to encompass this inclusive education philosophy in order to enable and empower families to become confident and competent in their approach and practice.

The design criteria identified during the needs analysis led to our development of a home learning pack in the form of a set of activity ‘cards’ linked to the four domains of learning rather than specific curriculum content. This meant that the activities would complement any existing education provision rather than replace it. The activity cards were made available to participants as a free resource in both pdf format and via a website, making them easily accessible and printable as appropriate to the needs of the family and their circumstance.

Introductory ‘cards’ explained how we had designed the pack and how the activities linked to the different domains of learning [14]. We were seeking to provide a range of activities in order to provide for the different needs, developmental stage and interests of the children and families. Participants were encouraged to choose those activities that they were drawn toward and interested in rather than having to complete all of them. Each domain of learning had its own set of between three and six activities to select from as set out in Table 2 below. Most were available in pdf format and on the website. Three of the physical activities were only available on the website so as to gain insight into how the website might be used.

Table 2.

Pack content.

Each activity was designed to be explained on two sides of a single A5 ‘card’. Each card set out the purpose of the activity, resources, and what to do, whilst on the back of the card were tips, extension activities and support for parents. We made it clear throughout that the separate areas of need are interrelated and that the contents of the pack were not designed to replace specialist setting activities but to complement them.

A colour scheme meant that each area of learning was branded with a distinctive colour so that different activities could be easily associated with their specific domain of learning. A key area of concern held by the researchers was the cultural appropriateness of the activities, and it was good to note that parents were overwhelmingly positive in this regard. The researchers took care during the design of the activities to ensure that the images and colour scheme used would be appropriate to Malaysian culture (such as avoiding yellow, as this colour was linked to royalty, and black, which is a colour for mourning, and replacing images of a dog with a cat, which is a preferred pet in Malaysia).

4.3. Evaluation Phase

After the home learning pack had been trialled with families, we moved to the evaluation phase with a focus on identifying the child’s level of interest and engagement with the activities, the parents’ experience of facilitating their child’s learning using the packs and any revisions needed for the pack design for the next cycle of research.

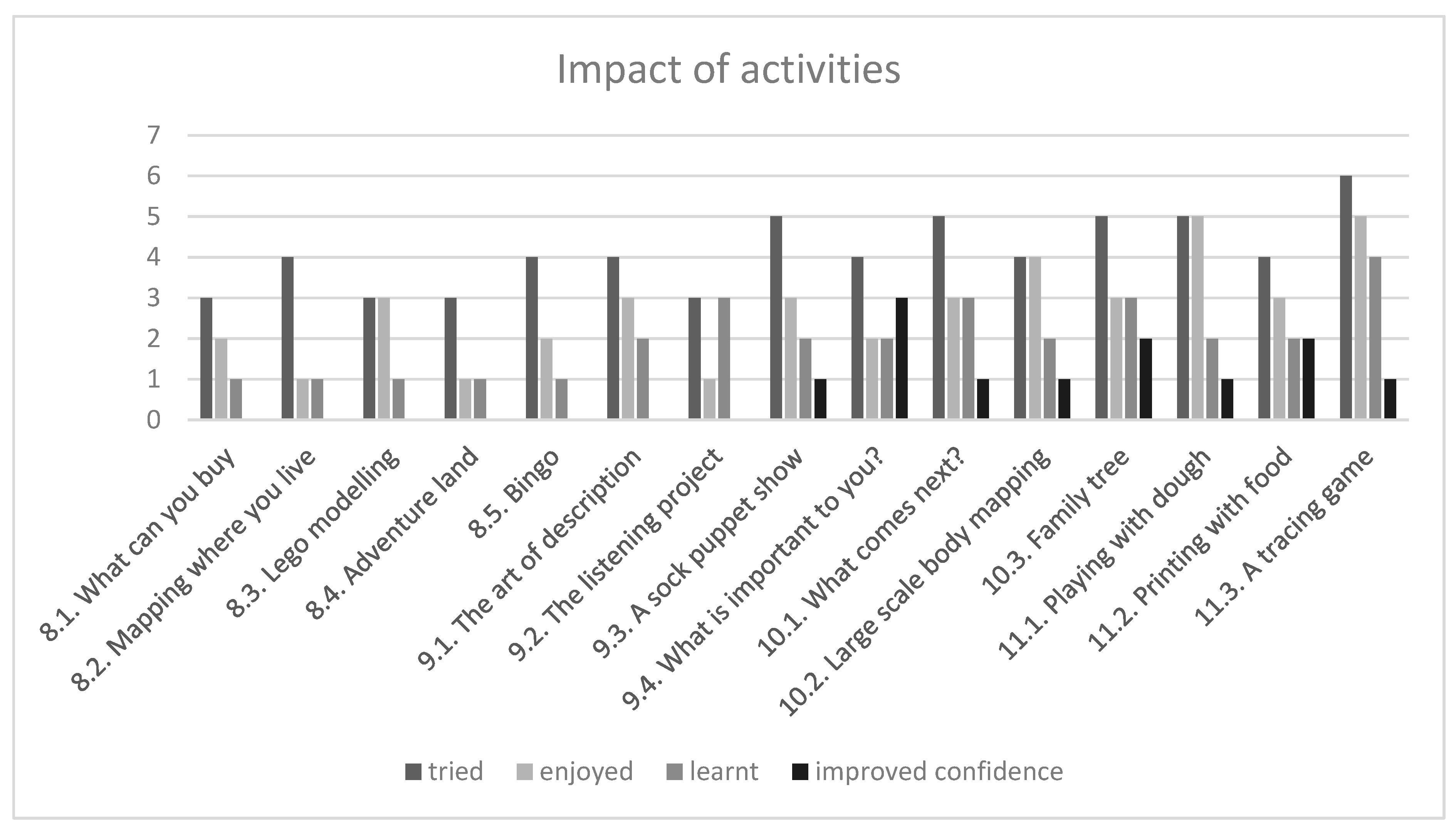

Whilst we encouraged families to choose only those activities they were interested in, within the participant group, all of the activities on the pdf cards were tried, and they provided a learning opportunity as summarised in Figure 1 below. Notably, none of the three additional activities for supporting physical development, which were available only on the website, were tried, despite parents stating that it was easier to access the website materials than pdfs. Feedback from two of the six parents highlighted an interest in accessing printed activity cards that they could easily return to in the future. This is a point of note for future cycles of this project if we are to ensure that the resources are made accessible for all.

Figure 1.

Impact of activities.

In terms of child engagement there was a particularly high level of interest (all parents) in the activities supporting social and emotional needs and sensory/physical needs. This confirms the findings from the initial needs analysis for activities to support these domains of learning and from the literature in terms of how the pandemic had a negative impact on social and emotional wellbeing during lockdown [46]. It highlights a need to provide home learning that is physical in nature and engages different senses as a basis for learning and for supporting social and emotional well-being.

The activities that provided the most enjoyment were the ‘sock puppet show’, ‘what comes next?’, ‘family tree’, ‘play dough’ and the ‘tracing game’. While all of the activities had been designed to be fun and engaging, these provided the most stimulation mentally and physically. They were also ranked highly in terms of supporting the child’s confidence in their abilities and the parent’s confidence in supporting their child’s learning, along with the ‘what is important to me?’ and ‘printing with food’ activities

4.4. Findings and Limitations

The repositioning of parents as educators during the pandemic has cast light on the challenges of providing suitable learning in the home. Of particular concern has been how parents are supported when their child has additional needs in terms of their knowledge and resources—their economic and cultural capital [6].

Whilst this has only been a pilot project, our initial findings indicated that parents felt more empowered to support their child’s learning at home, whilst five out of six parents felt that their child was more empowered to develop their own learning using the home learning packs. This was an important outcome and relates to the development and practice of an inclusive education philosophy that recognises the funds of knowledge [47] residing in families rather than locating knowledge exclusively with teachers in schools.

There was a range of families participating in this project with a variety of abilities and circumstances. This study was also conducted during lockdown, and it was possible that the parents were not able to engage with some activities to their fullest extent. Most of the limitations mentioned by the parents appeared to be focused on the time they had to work with their child stating that it was ‘challenging to keep the child focused to complete the activity due to surroundings at home’ (Parent 2). Another parent pointed out that their child lacked the ability to work independently, stating ‘my child would always need guidance to keep an eye on him during activities’ (Parent 3).

Whilst we had emphasised in the pack guidance that families should choose to access only those activities they are interested in and drawn towards, parents did comment on a need to provide activities suited to a range of abilities, stating that ‘Some activities may not suit/is too advanced for my child … Perhaps provide simpler activities for cognition and learning’ (Parent 4) and that ‘certain activities do show some interest to the child but maybe not all’ (Parent 3).

As a first cycle of DBR, these findings indicate promising results in terms of empowering parents and children in their learning at home. This is an element to build upon in the next iteration of the pack in addition to improving accessibility and providing activities suited to a wider range of needs and developmental stages.

5. Discussions

This study represents the first cycle of a design-based research project. It was developed in response to increasing demands in Malaysia and the UK to support families with children with ASD who were struggling to support their child’s learning during lockdown. The challenges faced by these families have brought to light issues of social justice, equity, access and inclusion. Engaging families in learning has become more significant in terms of the provision of educational experiences of children at home, in school and online [48]. This project has highlighted a need to empower families in their child’s learning at home and at school as part of an inclusive system of education that values the role of parents in their child’s education and recognises the knowledge [47] acquired outside of school. It highlights the role of familial habitus and capital in the field of education and how these can become barriers or enablers to learning at home.

5.1. Home Learning as Part of Inclusive Education

This study aimed to cast light on how families with children with ASD can be supported in their home learning as part of the philosophy of an inclusive education curriculum. We argue that when viewed through an inclusive education lens [9,24], ‘education’ encompasses more than the content of a national curriculum, and this is particularly important for children with additional needs who do not necessarily conform and fit into a mainstream system of education that is premised against a measurement of ‘normal’ development [45].

Schools and professionals need to re-consider their culture and practices to ensure that no one is left out [45]. Inclusion does not mean offering the same to everyone; it is about recognising the strengths and needs of the individual, working with children and their family to support those needs, and providing activities that build on the strength and competencies of children to enhance their development across all domains of learning.

5.2. The Role of Habitus, Capital and Field in Inclusive Education

The experiences and realities of home learning for families with children with ASD have highlighted the role of habitus, capital and field. For many children, home learning during lockdown took the form of online work set by the school following a national curriculum. This brought challenges in terms of a family’s ability to access the internet, the need for a learning space in the home for the child and the support for the child from the family in terms of curriculum knowledge and encouragement. Parents were expected to take on more significant duties to support the daily learning routines of their child [29], and, indeed, this research found that a main concern of parents was their time and resources.

The dispositions and attitudes for learning in the home, the habitus [13] of parents and that of their children, are influential in a child’s educational development. It takes time to change attitudes to learning and to reposition education as more than school. Not all families have the economic, social or cultural capital [38] to draw upon in order to support their child’s learning in terms of resource, knowledge or connections. Participants in this research felt under pressure to have their child conform to a ‘norm’ and to achieve in curriculum tests and, as such, viewed education as residing in a purely cognitive domain. Those with higher levels of capital were able to access additional support via specialist educational providers or resources. For those with less capital, the barriers of time, space and resource were significant.

5.3. Empowering Learning at Home

This research has highlighted the need for families to have choice and a significant say in the form of provision available for their children. This feeds into the inclusive education discourse in terms of the importance of empowerment. The design of the home learning packs needed to minimise the pressure on parents, to help lead a restrictive curriculum-based education in the home and to empower parents and children to recognise the learning that takes place every day through activity [33]. The design of the home learning packs aimed to do just this: to make links to everyday experiences such as shopping, to the development of a child’s mathematical knowledge. Valuing the authenticity of voice and everyday experience in this way raises the importance of a pragmatic, participant-oriented design, which would cater for the different learning needs of children with ASD.

The structure of the learning activities facilitated a capacity for discovery and independence for both parents and children. There was a recognition that an activity aimed at one domain of learning had threads that interlinked to all areas of a child’s learning and development. By explaining how a learning activity linked to a child’s development, the parents in this study felt empowered to support their child’s learning at home, and, at the same time, the children felt more empowered to develop their own home learning.

5.4. Developing Inclusive Education Policy

Inclusion is a global agenda and should be a goal for the education of all children [45]. Definitions of inclusive education are, however, a matter of debate both in country and internationally. In Malaysia, inclusive education is a relatively new concept with legislation changes in 2019 to ensure that no child is refused enrolment at any school of their choice, whereas an ‘inclusive education’ programme in Malaysia refers to a specialist educational programme for children with SEND that is separate to a mainstream class or school [49]. In England, inclusive education is focused on a parent’s right to send their child to a school of their choice; however, the education provided in that school is not necessarily inclusive. Instead, children with additional needs are compared to an ableist agenda [45] that positions those with SEND as a deficit and in need of segregation into specialist classrooms. Even the language of SEND positions those with identified needs as ‘other’, as outside of a ‘norm’. As countries across the globe were plunged into lockdown education in the home became an expected part of everyday life. This brings into question the place of ‘inclusive education’ in an era where education is located only in schools.

An alternative view of inclusive education is as a philosophy, an approach that values the abilities of the individual, diversity and interests. Here, education outside of school becomes part of inclusive education rather than separate from it. Relationships between child, parent, teacher, school and other professionals are strengthened by funds of knowledge in homes, schools and the community.

6. Conclusions

This research aimed to design a resource to support learning at home for families with children with ASD in England and Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic. A design-based research approach was adopted that invited settings, practitioners and families to contribute their views on home learning, thebarriers, enablers and aspirations. Findings from the first cycle of research highlight a need to empower parents and children in their education across all domains of learning via activities that engage the children, celebrate their funds of knowledge and relate to their everyday lives. In this way, economic, social and cultural barriers to education are reduced, and learning becomes meaningful and purposeful to each child whilst also supporting their education on a holistic level.

The need for inclusive education systems has been highlighted on a global level; however, definitions of inclusion remain unclear as children with additional needs remain segregated, othered from their peers and, in some casesconsidered as deficit. By repositioning inclusive education as a philosophy that focuses on the capabilities of children, learning becomes a construction arising between children, their families and teachers [24].

Learning in the home during and following the pandemic thus becomes a key and core part of inclusive education provision. Rather than seeing it as separate from what takes place behind the school gates, undervalued and not adequately resourced, we argue for inclusive education policies and provisions that engage with home learning as a complementary and essential component of inclusive education pedagogy for all learners’ progress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization V.B.; methodology, V.B. and Y.L.L.; formal analysis, V.B. and Y.L.L.; investigation, V.B. and Y.L.L.; resources, V.B.; data curation, V.B., Y.L.L. and T.J.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B., S.G., Y.L.L. and T.J.N.; writing—review and editing, V.B., S.G., Y.L.L. and T.J.N.; visualization, V.B.; supervision, V.B. and S.G.; project administration V.B.; funding acquisition, V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the topic.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Morton, R. Home education: Constructions of choice. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2010, 3, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, N.; Doughty, J.; Slater, T.; Forrester, D.; Rhodes, K. Home education for children with additional learning needs–a better choice or the only option? Educ. Rev. 2020, 72, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludgate, S.; Mears, C.; Blackburn, C. Small steps and stronger relationships: Parents’ experiences of homeschooling children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2022, 22, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, A.; Ogurlu, U.; Logan, N.; Cook, P. COVID-19 and Remote Learning: Experiences of Parents with Children during the Pandemic. Am. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld, M.; Soland, J.; Tarasawa, B.; Johnson, A.; Ruzek, E.; Liu, J. Projecting the Potential Impact of COVID-19 School Closures on Academic Achievement. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, T.R.; Prasad, S.; Munzer, T.; Laventhal, N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Pediatr. Rehabil. Med. Interdiscip. Approach 2020, 13, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilholm, C. Research about inclusive education in 2020–How can we improve our theories in order to change practice? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 36, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. 2022. Available online: http://www.csie.org.uk/ (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Allan, J. Inclusive education, democracy and COVID-19. A time to rethink? Utbild. Demokr. 2021, 30, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C. Disability, higher education and the inclusive society. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2007, 28, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, L. Inclusive Education and Teacher Education: A Basis for Hope or a Discourse of Delusion? Institute of Education: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.-C. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, C. Education, inequality and social justice: A critical analysis applying the Sen-Bourdieu Analytical Framework. Policy Futur. Educ. 2019, 17, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education; Department of Health. Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years Statutory guidance for organisations which work with and support children and young people who have special educational needs or disabilities. In DFE-00205-2013; Department for Education: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dockrell, J.; Lindsay, G.; Roulstone, S.; Law, J. Supporting children with speech, language and communication needs: An overview of the results of the Better Communication Research Programme. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2014, 49, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wearmouth, J. Effective SENCo. Meeting the Challenge; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Denham, S.; Watts, S. The SENCo Handbook. Leading Provision and Practice; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. Construction of Reality in the Child; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. Thought and Language; Hanfmann, E., Vakar, G., Kozulin, A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. The Behaviour of Organisms; Appleton Century Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C. Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory; Constable: London, UK, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occupational Therapy Helping Children. What Is Proprioception and Why Is It Important? Occupational Therapy Helping Children. 2021. Available online: https://occupationaltherapy.com.au/proprioception/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Klibthong, S. Re-Imagining Inclusive Education for Young Children: A Kaleidoscope of Bourdieuian Theorisation. Int. Educ. Stud. 2012, 5, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyema, E.M.; Eucheria, N.C.; Obafemi, F.A.; Sen, S.; Atonye, F.G.; Sharma, A.; Alsayed, A.O. Impact of Coronavirus Pandemic on Education. J. Educ. Pract. 2020, 11, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, R.; Catarino, S.; Miragaia, P.; Ferreras, C.; Viana, V.; Guardiano, M. The impact of COVID-19 on children with autism spectrum disorder. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 71, 285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Done, E. The role pressures for Special Educational Needs Coordinators as managers, leaders and advocates in the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for inclusive education. Med. Res. Arch. 2022, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.X.; Lau, B.T. Parental Perceptions, Attitudes and Involvement in Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders in Sarawak, Malaysia. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2018, 29, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L. Changing balance of care in Covid-19 lockdown for children with autism. J. Clin. Case Rep. Online 2020, 1, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spain, D.; Mason, D.; Capp, S.J.; Stoppelbein, L.; White, S.W.; Happé, F. “This may be a really good opportunity to make the world a more autism friendly place”: Professionals’ perspectives on the effects of COVID-19 on autistic individuals. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2021, 83, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Design-Based Research Collective. Design-Based Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational Inquiry. Am. Educ. Res. Assoc. 2003, 32, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. Paradigms Lost and Pragmatism Regained. Methodological Implications of Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakkary, R.L. Experiencing Interaction Design: A Pragmatic Theory; Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Plymouth: Plymouth, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.; Burbules, N. Pragmatism and Educational Research; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 7th ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, L. What counts as evidence of inclusive education? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R. Power and trust: An academic researcher’s perspective on working with interpreters as gatekeepers. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hebl, M. Descriptive Statistics. In Introduction to Statistics; Lane, D., Ed.; Rice University: Houston, TX, USA, 2003; pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Watson, S.; Adams, J.; Brook, K.; Charman, T.; Crane, L.; Cusack, J.; Leekam, S.; Milton, D.; Parr, J.R.; Pellicano, E. Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism 2019, 23, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research; BERA: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.J.; Bravi, R.; Minciacchi, D. The efect of fdget spinners on fne motor control. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3144–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.; Eerde, D.V. An introduction to design-based research with an example from statistics education. In Doing Qualitative Research: Methodology and Methods in Mathematics Education; Bikner-Ahsbahs, A., Knipping, C., Presmeg, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 429–466. [Google Scholar]

- Runswick-Cole, K. Time to end the bias towards inclusive education? Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2011, 38, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Sun, T.; Zhu, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Chen, Q.; Peng, G.; Zhao, D.; Yu, H.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children with ASD and Their Families: An Online Survey in China. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volman, M.; Gilde, J.T. The effects of using students’ funds of knowledge on educational outcomes in the social and personal domain. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2021, 28, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.H.; Foy, K.; Mulligan, A.; Shanks, R. Teaching in a third space during national COVID-19 lockdowns: In loco magister? Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M. The Zero Reject policy: A way forward for inclusive education in Malaysia? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 27, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).