Abstract

This study focused on professor leadership styles and investigated the impacts of various leadership characteristics on student academic performance as well as students’ perceptions of class engagement and trust toward a professor. Using multiple leaderships styles to estimate a model of the relationship between faculty leadership styles and student outcomes provides for a broader view compared to previous research. The empirical results indicated that student perception of class engagement was significantly influenced by a professor’s emotional leadership, Pygmalion leadership, and charismatic leadership. Further, student perception of trust toward a professor was significantly affected by the professor’s transformational leadership, Pygmalion leadership, and charismatic leadership. Lastly, student academic performance was significantly impacted by class engagement. This research provides practical applications for enhancing student academic performance with the adoption of relevant leadership styles in higher education classes.

1. Introduction

Even before the pandemic struck, higher education faced enrollment challenges. Most of us working in higher education continue to observe and believe in the benefits of a university experience and a college degree, but some do question the value proposition. New sources and organizations provide sound information for establishing an ROI (return on investment) for various degrees measured by the number of years a student takes to complete the degree [1]. This information adds to the skepticism about a university education but also demonstrates that students who start a degree and maintain a steady path to completing the degree in four years are much more likely to reap a financial benefit from their college experience.

Naturally, the pandemic slowed many students on the path to completion. Some students stepped out of their degree programs; some individuals chose to delay or even forego higher education. There has been ample news coverage of declining university enrollment, particularly from first-year students [2]. In addition to declines in first-year students, underserved students are also returning at a lower rate [2,3]. The “Great Interruption” is a phrase that describes the phenomenon of the declining university enrollments resulting from the disruption of COVID-19 [4].

Clearly, some universities and degree programs have been hit harder than others. The conditions have led to universities consolidating or closing, departments being eliminated, and program offerings being reduced [5]. The universities hardest hit are those serving low-/middle-income students and underserved students [5].

The post-pandemic era of higher education is likely to have a dramatically different history. Universities are having to approach recruiting and retention in a more effective manner. Many of the reasons for which students leave higher education or transfer universities have been carefully studied. Some of the reasons are more easily documented and measured, such as finances, illness, deployment, etc. [6,7]. However, students also fail to complete college, switch majors, and transfer for reasons that are less easily measured, including concerns about environment, social interactions, isolation, and fit [6,7]. Additionally, a detailed report on transfer and mobility emphasized that universities need to facilitate degree completion in short periods of time in order to achieve a positive value proposition for students [8].

In an effort to recruit and retain students, research has examined student academic achievements as a means for enhancing the performance of institutions and increasing the competitive advantage of students in the job market [9]. Though prior research has been conducted to predict and explain student academic performance based on learning styles and environment [10,11], less attention has focused on leadership styles of the professor. Adjusting to individual learning styles and changing the learning environment can be outside of the professor’s control [9], but professors can control their interactions with students. Therefore, professor roles and abilities to lead their classes should be considered [12,13]. This research explores how professors can support performance by encouraging student engagement and building trust through the use of an effective leadership style. Additionally, our research adds to the body of knowledge on leadership by examining multiple leadership styles concurrently. In order to support the development of a model that tests leadership styles concurrently, this paper focuses only on the role of the professor.

2. Literature Review

This study considers professor leadership styles as a core determinant of student class engagement, trust toward the professor, and academic performance. In class, a professor is required to actively interact with students to foster their achievements via assignments, quizzes, and exams, leaving many potential opportunities for student failures to occur. When student performance is lower than expectations, professors should provide authentic feedback and encouragement to the students regardless of their learning motivations or situations [14,15]. As the leader of the class, professors should provide direction and encouragement for their students to engage in course activities and to persevere throughout the semester. Further, by utilizing effective leadership skills, the professor can gain student trust and enhance performance.

The well-documented association between leadership and performance from the human resource management literature [16,17] suggests that a similar relationship may occur in the undergraduate classroom. Therefore, this study proposes that professors, serving as a leader in the classroom, can apply leadership theories to positively influence student academic performance and increase the students’ trust of the professors. Given that a student’s intrinsic learning motivations to enhance academic performance can vary greatly across students within a classroom, and these intrinsic learning motivations are influenced by many variables, professors often strive to create learning experiences that students find interesting and gratifying.

There are related studies that have explored the influence of professor leadership styles on student academic performance. These prior studies have typically focused on a single leadership style rather than considering the professor’s actual leadership style or multiple leadership styles simultaneously (e.g., transformational leadership [9]; Pygmalion leadership [15]; transactional leadership [18]). Utilizing approaches found in the human resources literature, this study assumes that professors may be practicing various leadership styles, and that each leadership style has different influences on student perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors in the class. For example, some professors have a high level of the leadership skill to empathize with students’ emotions and feelings (i.e., emotional leadership) [19]. In addition, some professors establish clear exchange relationships with their students in class, appealing to the students’ self-interest (e.g., rewards or punishments depending on their levels of achievement) (i.e., transactional leadership) [20].

Although types of managerial leadership, such as emotional leadership and charismatic leadership, have been studied as core determinants of followers’ work-related performance in the human resource management field, prior research in the education area has focused mainly on a professor’s transformational, Pygmalion, or transactional leadership to predict students’ academic performance [9,15,18]. It is plausible that effective leadership styles could enhance class engagement, student trust, and, ultimately, overall student academic performance. This study adds to the body of knowledge by examining student responses to multiple leadership styles concurrently.

2.1. Professor Leadership Styles

To contribute to the existing literature on education, this study proposes five types of professor leadership styles as core determinants of student class engagement, trust toward the professor, and academic performance based on social exchange theory and human resource management literature. As there are many leadership styles, it was impossible to include them all in this single study. An important part of the development of our model required a selection of a subset of leadership styles that offered depth and breadth of leadership characteristics.

The next step was to narrow the various leadership styles to those applicable to higher education. For example, several articles consider the effectiveness of applications of transformational leadership in an academic setting [21,22]. Collectively, the results of these studies support the inclusion of transformational leadership. The decision to retain certain leadership styles was also supported by the human resources literature. For example, the authors of [23] examined the construct of emotion and its impact on teamwork. This relationship supported the inclusion of emotional leadership in a higher education environment in which team assignments are commonplace. Additionally, the management literature indicates the value of constructive feedback associated with a Pygmalion leadership style [24]. In academics, constructive feedback is important for the learning process. Furthermore, transactional leadership is associated with improved performance, as demonstrated in the psychology literature [25], and the leadership literature [26] confirms that a charismatic leader motivates individuals towards achievement based on a clear vision and inspiration. Other research that guided our selection of leadership styles included the following: studies on transformational [18,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], emotional [34,35,36], Pygmalion [15,16,37], transactional [18,30,38,39], and charismatic leadership [28,40,41]. Ultimately, this body of literature provided the justification for the inclusion of the five leadership styles in this study as they relate to higher education.

As a theoretical contribution, this study adds to and elaborates on the distinct impact of a professor’s various leadership styles on students. Furthermore, from a practical perspective, compared to prior research that was focused on the perspective of students, the current research emphasizes the critical role of professor leadership styles in class, which may allow for professors and institutions to develop pedagogical strategies that enhance student academic performance.

2.1.1. Transformational Leadership

The learning process is changing, so learning also needs transformation [42]. Transformational leadership focuses on followers’ long-term vision for their self-development and self-transformation into leaders [43]. Periods of crisis or change support the emergence of transformational leadership [44,45]. Although there is some disagreement in the literature regarding the definition and application of the concept of transformational leadership [44], there is justification for its inclusion in this study.

Research in the education field indicates that the effects of transformational leadership in a work environment may be applicable to an instructional setting [21,22,27,30,31]. In an educational context, an instructor’s transformational leadership style can influence students to engage in class, feel connected with the instructor, and develop a motivation to learn [46]. Compared to transactional leadership, transformational behaviors by the professor have a stronger link with student learning and instructor credibility perceptions [47]. Transformational leadership in the classroom may also lead to a higher level of employee engagement in the workplace by alumni who received inspiration from their former professor [48]. Based on previous literature, transformational leadership in this study is defined as a professor’s leadership style to transform, motivate, and enhance students’ learning actions via organizing the student collective learning purpose [49]. Hence, because instructors with a highly developed style of transformational leadership tend to be more committed, dedicated, and motivated to teach and interact with students, they are more likely to be motivated by the students as well [46].

According to [20], transformational leaders (1) recognize their followers’ strengths, personal goals, and development needs, (2) consistently improve their followers by challenging entrenched values and assumptions, (3) motivate the followers to behave in accordance with a shared purpose and long-term vision, and (4) focus on developing the followers’ pride in accomplishments. Thus, transformational professors have high academic performance expectations from students, provide an appropriate model, offer intellectual stimulation, provide individualized support, foster group goal acceptance, and identify and articulate a shared vision [46,50].

2.1.2. Emotional Leadership

Emotional leadership focuses on the emotional traits of individuals, such as empathy [35]. Emotional leaders have a higher level of ability to perceive their own and their followers’ emotions and feelings, as well as to simultaneously manage their own and their followers’ emotions and feelings [51]. Thus, a professor’s emotional leadership emphasizes the characteristic of emotional intelligence that empathizes with students’ emotions and feelings, while re-experiencing the same. Emotional leadership allows a leader to understand others’ emotions and feelings and then naturally contribute to their problem solving and pattern recognition by identifying with those problems [35].

Compared to other leadership styles (oriented to followers’ task performance), emotional leadership focuses on current relationships with followers [23]. In other words, an emotional leader encourages followers to maintain confidence when they are required to complete challenging tasks rather than exert pressure on the followers [35]. This is because emotional leadership can allow a leader to identify followers’ strengths and weaknesses for completing the tasks and accurately read their nonverbal cues, feelings, or moods while interacting with them [19]. In addition, followers who work with an emotional leader are more likely to speak their minds and express sensitivity and understanding, which makes them manage their emotions well in a work setting. Consequently, a professor’s emotional leadership can serve an important role in establishing and maintaining a close relationship with students in class.

2.1.3. Pygmalion Leadership

Pygmalion leadership focuses on the impact of a leader’s positive expectations of followers’ performance in a work environment [52]. In other words, leaders who practice Pygmalion leadership tend to make followers perceive that their leaders have high expectations of the followers’ capabilities and performances. The management literature has indicated that one of the ways to demonstrate a Pygmalion leadership style is to offer constructive feedback and challenging opportunities by emphasizing the leader’s belief that followers will be able to succeed [24].

It is possible that this applies to a classroom leader as well. The application of this concept to a classroom would suggest that a professor with a high level of Pygmalion leadership creates a supportive class environment, helping students to improve their academic performance. Thus, students feel free to express their views and opinions and attempt to gain more attention from the professor in order to meet the professor’s high expectations. Furthermore, the professor tends to offer opportunities to the students to display exceptional academic performance through challenging assignments and tasks. Lastly, the most important role of the professor is to provide the students with appropriate feedback by echoing high expectations, praising the students, or leaving constructive comments [16,53]. In effect, the professor’s climate, input, output, and feedback (e.g., praise) result in student success or failure in class, depending on how much the students struggle to meet the professor’s expectations [37].

The impact of a professor’s Pygmalion leadership on student academic performance is based on the relationship between the professor’s expectation-based behavior and the students’ behavior. In other words, the expectation cannot solely enhance student academic performance and change their behavior. For example, the expectation about students enables the professor to formulate high levels of supportive attitudes toward them, which leads the professor to invest more energy toward the students with potential [54]. Hence, a professor’s Pygmalion leadership will influence students’ behavioral intentions and actual behaviors, since students appreciate that the professor acknowledges their potential in class [52].

2.1.4. Transactional Leadership

Compared to other leadership styles that focus on followers’ intrinsic needs, transactional leadership is based on followers’ extrinsic needs or self-interest by focusing on the exchange relationship between a leader and followers [17,20]. For example, a professor who practices transactional leadership clarifies students’ responsibilities, rewards them for meeting the class objectives and goals, and corrects (or punishes) them when they cannot meet the class objectives and goals. The ultimate goal of transactional professors may be to establish clear expectations and goals in class and generate higher levels of students’ academic performance by providing them with appropriate rewards (when they are above the expectation) or punishments and constructive feedback (when they are below the expectation) according to the fundamental notion of transactional leadership [25]. Thus, one of the advantages of transactional leadership is to quickly correct followers’ actions that need improvement, which leads to followers’ immediate improvements to be rewarded [39].

A transactional leader’s reward serves as a motivational factor for followers to meet the leader’s expectations and goals and to perform better in a work setting. Further, a transactional leader’s punishments motivate followers to avoid failures and mistakes to meet their leader’s expectations and goals and to engage in better work performance [17]. In class, transactional professors tend to establish clear expectations, goals, rewards, and punishment standards. They motivate students to accomplish specific assignments to earn rewards by doing better and to avoid punishments by working hard. However, a transactional professor also provides constructive feedback to lower-performing students in addition to the punishments to make them perform better in class.

2.1.5. Charismatic Leadership

Similar to other areas of leadership styles, there is some disagreement among scholars regarding the development of charismatic leadership [55]. Charismatic leadership is based on followers’ perceived evaluation of a leader’s characteristics and behavior [40]. More specifically, the reflection of people, tasks, and participative orientation of a leader’s characteristics and behavior determines whether followers interpret the leader as charismatic. A charismatic leader also tends to possess the ability to articulate and formulate an inspirational vision and to foster followers’ impression that the leader is extraordinary [40]. The leader’s extraordinary character and inspirational vision entice followers to decide to follow that leader without reservation. Therefore, the attributes of charismatic leadership serve as signals for followers, such as a leader’s use of metaphors and symbols, passionate and expressive communication skills, and articulation of values [26]. The study in [55] noted the behaviors and attributions of charismatic leadership: (1) “Justifying the mission by appealing to values that distinguish right from wrong; (2) Communicating in symbolic ways to make the message clear and vivid, and also symbolizing and embodying the moral unity of the collective per se; and (3) Demonstrating conviction and passion for the mission via emotional displays” (p. 304).

In addition to the above attributes, charismatic leadership attracts attention, motivates followers emotionally and intellectually, focuses on collective identity, provides a clear vision, rapidly responds to contextual and environmental cues, and influences others in an organization [56]. In the same way, a professor’s characteristics serve as signals for students’ perceptions of charismatic leadership by showing the professor’s abilities to minimize the perceived risks of coordination and cooperation challenges, inspire and offer a clear vision and goal, and attract their attention in class. Further, a professor who is experienced with charismatic leadership can direct students toward shared goals, such as academic achievements.

2.2. Class Engagement, Trust toward Professor, and Academic Performance

According to the education literature, students formulate perceptions of class engagement by combining experiences with a professor and peers, academic challenges, grades, motivation, class environment, self-efficacy, and participation [57]. However, most research in this field has focused on the psychological aspect of student class engagement based on employee work engagement, such as affect, cognition, and behavior [58]. Hence, student class engagement is defined as highly pleasurable emotional (affect), cognitive (cognition), and behavioral (behavior) involvement in class activities [9,59]. More specifically, regarding excitement and enthusiasm, the emotional aspects of class engagement emphasize activated and pleasurable feelings and emotions of students while taking a class and/or participating in class activities. Cognitive aspects focus on the moment when students concentrate in class and pay attention to the professor by being fully absorbed in the class and class activities. Lastly, behavioral aspects are based on students’ exerting extra energy and effort for the class and class activities through enthusiastic interactive behaviors.

In relationship marketing literature, trust is considered a critical aspect of maintaining an exchange process and as a fundamental relationship that builds a psychological block between two parties [60]. Within the education context, if students trust a professor in class, they will perceive the relationship with the professor as more valuable, which leads them to retain the relationship. Further, one party’s high level of trust toward the other party in the relationship develops the perceptions of integrity and reliability as well as a belief that the other party brings only positive consequences [61,62]. Hence, students’ trust toward a professor can be exhibited by the confidence of the professor’s goodwill for them in class. This belief results in one party’s integrative behavior (i.e., students in this study), which consequently leads them to maintain the relationship with the other party (i.e., professor in class in this study) [63].

Academic performance serves as a critical indicator that evaluates an instructor’s course quality assurance and predicts students’ learning outcomes [64]. Students should develop learning skills, strategies, and approaches while taking a course by actively interacting with the instructor and consuming the whole course content to achieve good academic performance [65]. According to prior research in the education field, students are required to use both general and specific learning approaches and strategies [64,66,67]; however, general approaches can be developed by students’ own cognitive strategies, whereas specific ones can be enhanced by help-seeking and peer-learning from an instructor. Therefore, it is critical to consider the role of a professor’s leadership style in class in predicting students’ overall academic performance.

2.3. Hypotheses Development

The social exchange theory is based on the notion that voluntary actions of individuals are “motivated by the return they are expected to bring and typically do in fact bring from others” [68] (p. 91). The exchange between individuals and others focuses on the norms of reciprocity [68,69]. Hence, it is assumed that individuals may retain the exchange process when reciprocations (or benefits) occur as expected. Reciprocations enable individuals to create psychological obligations and attempt to return them to others by maintaining the exchange relationship [69]. According to [33], an exchange relationship between two parties begins with a short-term relationship, and then a long-term relationship is established. More specifically, a short-term relationship is established by exchanges of tangible materials between two parties. Based on the exchange process, two parties develop a long-term relationship by mutual commitment and trust, such as emotionally added relationships [68]. Within the education context, student class engagement and trust toward a professor may serve as a “psychological pull-to-stay force” in class. For example, when students establish the exchange relationship with their professor in class and receive benefits from the professor (i.e., through leadership styles in this study) (short-term relationship), they may feel obliged and indebted to return the favor by attempting to remain and work hard in class (i.e., class engagement and academic performance in this study) (long-term relationship) [70].

In class, a professor and students exchange information, resources, and class-related benefits under the professor’s leadership, and depending on the leadership style, students can be induced into trusting the professor and engaging in class. In the human resource management field, a manager becomes a specific target, motivating followers to engage in favorable attitudes and behaviors for the target [33]. Within the context of this study, when students trust the professor and engage in class, they experience a high level of relational obligation with the professor and the class, which motivates them to work hard in class (i.e., enhanced academic performance). Based on the aforementioned notions, this study establishes and tests the following alternative research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Transformational leadership is positively associated with class engagement (H1a) and trust toward professor (H1b).

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Emotional leadership is positively associated with class engagement (H2a) and trust toward professor (H2b).

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Pygmalion leadership is positively associated with class engagement (H3a) and trust toward professor (H3b).

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Transactional leadership is positively associated with class engagement (H4a) and trust toward professor (H4b).

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Charismatic leadership is positively associated with class engagement (H5a) and trust toward professor (H5b).

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Class engagement is positively associated with academic performance.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Trust toward professor is positively associated with academic performance.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

The authors worked with Qualtrics (a web-based survey company) for data collection from online panel samples of students who are currently enrolled in undergraduate programs in the United States. This purposive sampling method enables the authors to avoid any potential impacts of geographic and cultural differences on the research findings [71]. Qualtrics shared a web survey link with its active panel members who are currently enrolled in undergraduate programs in the United States. To arouse each participant’s perceptions of a favorite professor before answering the survey items, the first page of the questionnaire had the following open-ended questions: (1) “What is the first leadership characteristic that comes to mind when thinking of your favorite professor?”; (2) “What is the second leadership characteristic that comes to mind when thinking of your favorite professor?”; and (3) “What is the third leadership characteristic that comes to mind when thinking of your favorite professor?” The authors carefully reviewed each answer to check whether the characteristics were closely related to a professor’s leadership styles before finalizing the dataset (e.g., honest, nice, caring, helpful (appropriate) vs. money, rich, none (inappropriate)). Consequently, 15 participants were removed during the data purification procedure, and 200 participants were retained for further data analyses. Of the participants, most students (142) self-identified as female (71%); 47.5% were Caucasian, followed by Hispanic (15%) and African American (13.5%); 28.5% of the participants were sophomores, and 28.5% were juniors, followed by freshmen (21%).

3.2. Measures

Given that this study required respondents to consider several leadership styles, it was necessary to reduce previously used scales to include only those items that could feasibly represent the leadership styles included. A subset of questions from the existing literature were selected to help avoid respondent fatigue, and the measures were subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis (e.g., Pygmalion leadership was measured with Rosenthal’s brief summary of four factors, including climate, input, output, and feedback rather than full items). Additionally, it was necessary to modify scales that were previously validated to be relevant for an educational context. For example, this study used the revised scales of Balwant et al. [9] to measure class engagement originally from engagement in the human resource management field. The scales were modified to specifically relate the leadership theory to a classroom setting. Questions retained in this study demonstrated high loading on the factors developed, and each scale achieved an alpha of 0.792 or higher.

All measures for each construct are indicated in Table 1. Each item was adapted from prior research and revised through the back-and-forth method by the authors for this study’s context (e.g., focusing on a professor’s leadership style instead of those of a manager in a workplace). The authors selected the items after checking how well the measures were conceptually developed and empirically tested in a rigorous manner. All items except for the academic performance measure were measured with a 7-point Likert-type scale (“1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree”). For the academic performance construct, the participants were asked to indicate their academic performance in their favorite professor’s class within the range of their grade percentage (from 0 to 100 percent). The authors also attempted to control common method bias by randomly ordering the survey items as a procedural remedy, as exhibited in the study of [72].

Table 1.

Measurement Model from CFA.

4. Methods and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

The two-step approach of [73] was employed in this study to test the reliability and validity of each indicator before testing the research hypotheses via a path analysis. With SPSS 26.0, the authors checked the reliability by assessing the respective Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all measures. During this stage, the academic performance construct was excluded, because it was measured with one item. Table 1 indicates that the reliabilities of all measures were confirmed by exceeding an acceptable level (0.70) in the social science field (i.e., transformational leadership = 0.892, emotional leadership = 0.870, Pygmalion leadership = 0.792, transactional leadership = 0.808, charismatic leadership = 0.798, class engagement = 0.887, and trust toward professor = 0.869) [74]. After confirming the reliability, the authors performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with AMOS 26.0 to test the convergent validities of all indicators. Before doing so, the authors checked all indicators’ kurtosis and skewness for confirming the data’s normal distribution (i.e., all indicators were not greater than +1 or lower than −1). As indicated in Table 1, all indicators’ critical ratios that signified the convergent validity were statistically significant (i.e., more than 2.58, p < 0.01) [75].

Although the fit indices of the measurement model were less than the acceptable values in general, the authors decided to test each hypothesis based on the notion that “more complex models with smaller samples may require somewhat less strict criteria for evaluation with the multiple fit indices” [75] (p. 654). In this study, the measurement model had 39 indicators with 200 samples, the measurement model’s χ2/d.f. value was less than 2.5, and the RMSEA value was also less than 0.08. In addition, the authors expected that each hypothesis had the potential to make meaningful contributions to the extant literature on education.

Further, the authors assessed the discriminant validity of all indicators by performing multiple CFAs with each pair of constructs with respective measures, as exhibited by the approach of [76]. The authors compared the chi-square and degree-of-freedom values of each unconstrained model (i.e., assuming the two constructs are different) with those of each constrained model (i.e., assuming the two constructs are the same). It resulted in one value difference in the degree of freedom between the two models. In this case, if the chi-square values’ difference between two models is greater than 3.84, the two constructs are significantly discriminated in the significant level of 0.05. Table 2 demonstrates that all constructs signified discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Chi-square difference test for discriminant validity of the measures.

This study performed Harman’s one-factor test as the last step before moving all measures forward to a path analysis to empirically test common method bias [77]. The authors compared the chi-square = 1363.758 and degree of freedom values = 675 of the measurement (multidimensional) model with those of the one-factor model (chi-square = 2102.404, degree of freedom = 702). Since the chi-square and degree of freedom values of the measurement model were better than those of the one-factor model, the authors concluded that common method bias might not be a serious issue in this study.

4.2. Testing of the Research Hypotheses

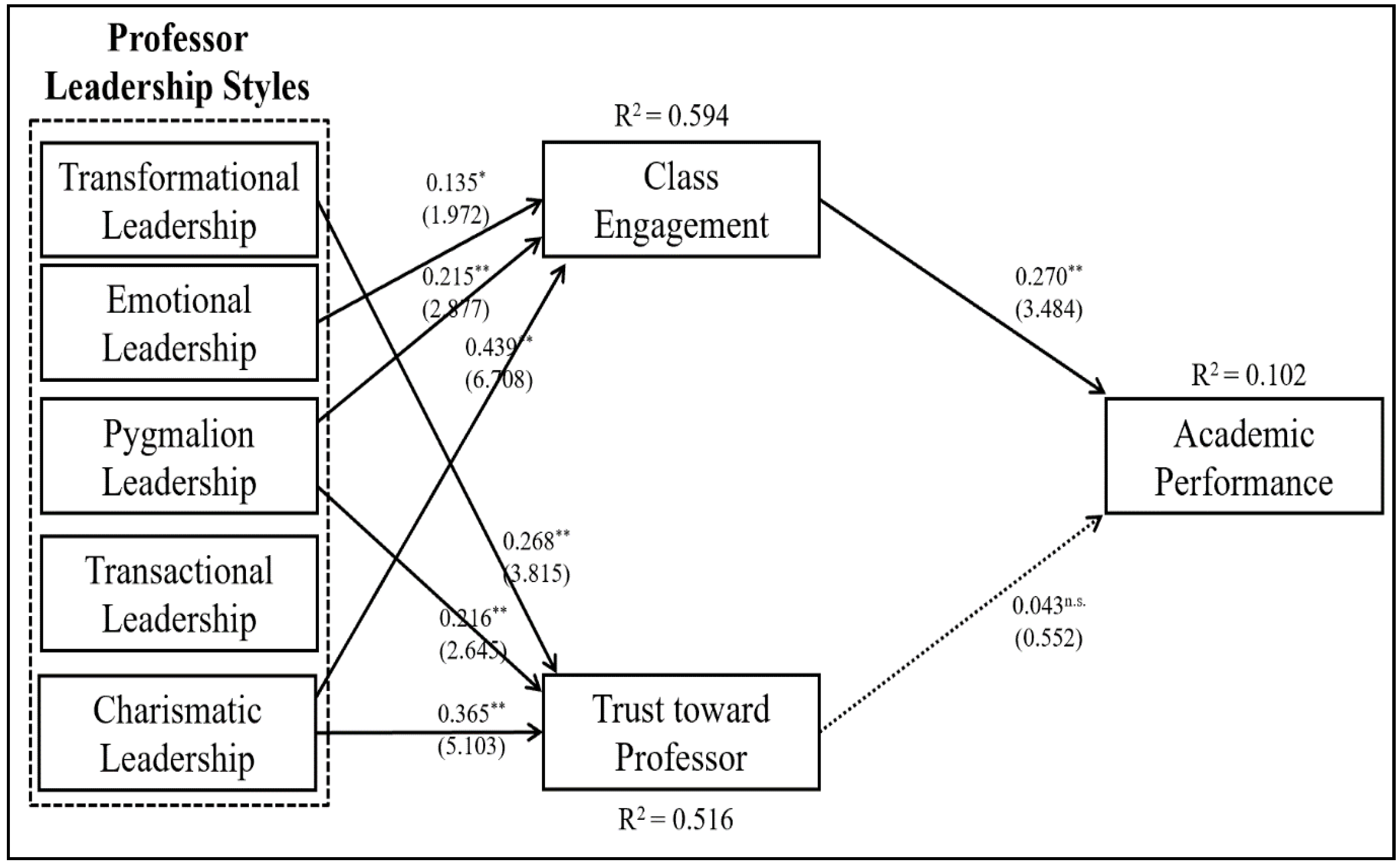

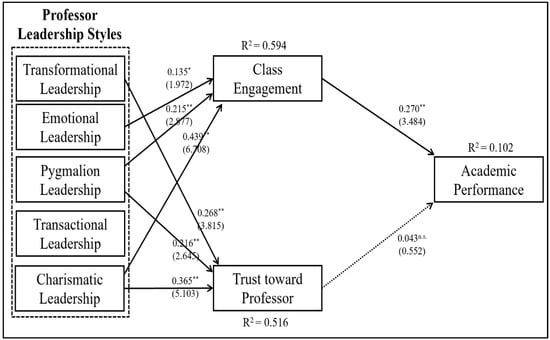

The authors conducted a path analysis via AMOS to empirically test the research hypotheses by using the means of all measures for each construct that signified the reliability and validities. According to [75], a path analysis “employs simple bivariate correlations to estimate relationships in a structural equation modeling and seeks to determine the strength of the paths shown in path diagrams” (p. 616). Since the main purpose of this study was to rigorously examine which leadership style has a stronger impact on students versus those of others (i.e., comparing relative strengths of each path), this study used a path analysis as one type of structural equation modeling approach. The research model’s fit indices are demonstrated under Table 3, and Figure 1 illustrates maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) for the research model’s parameters.

Table 3.

Standardized parameter estimates.

Figure 1.

Estimates of path analysis. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, n.s. = no significance. Note: Only significant paths are demonstrated (except for the path from trust toward professor to academic performance).

Table 4 provides a summary of the results. H1a was not supported, because transformational leadership’s impact on class engagement was not statistically significant (coefficient = 0.101, critical ratio = 1.580, p > 0.05); H1b was supported, as transformational leadership was significantly related to trust toward the professor (coefficient = 0.268, critical ratio = 3.815, p < 0.01). H2a was supported, because emotional leadership had a significantly positive impact on class engagement (coefficient = 0.135, critical ratio = 1.972, p < 0.05), but H2b was not supported, since emotional leadership’s influence on trust toward the professor was not statistically significant (coefficient = 0.069, critical ratio = 0.932, p > 0.05). H3a and H3b were supported because of Pygmalion leadership’s significant impact on class engagement (coefficient = 0.215, critical ratio = 2.877, p < 0.01) and trust toward the professor (coefficient = 0.216, critical ratio = 2.645, p < 0.01). H4a and H4b were not supported due to transactional leadership’s insignificant effects on class engagement (coefficient = 0.000, critical ratio = −0.002, p > 0.05) and trust toward the professor (coefficient = −0.103, critical ratio = −1.466, p > 0.05). H5a and H5b were supported, because charismatic leadership significantly influenced class engagement (coefficient = 0.439, critical ratio = 6.708, p< 0.01) and trust toward the professor (coefficient = 0.365, critical ratio = 5.103, p < 0.01). Lastly, there was support for H6 but not for H7, because academic performance was significantly affected only by class engagement (coefficient = 0.270, critical ratio = 3.484, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Test of hypotheses summary.

Interestingly, all types of leadership styles had statistically significant covariances with trust toward the professor, class engagement, and academic performance according to the results of CFA. However, when the correlations were changed to the causal relationships, the impact of transactional leadership on class engagement and trust toward the professor was insignificant, the effect of transformational leadership on class engagement was insignificant, and the influence of emotional leadership on class engagement was insignificant because of the relatively strong power of other leadership styles’ influences on class engagement and trust toward the professor. From a statistical perspective, the relatively strong power tends to make the respective impacts of transformational leadership, emotional leadership, and transactional leadership on class engagement and trust toward the professor weaker [78]. Hence, it is arguable that Pygmalion leadership and charismatic leadership styles could be more powerful determinants of class engagement, trust toward the professor, and academic performance.

The authors tested the indirect effects of a professor’s leadership styles on student academic performance via class engagement in addition to their direct effects (i.e., trust toward the professor could not be a mediator, because its impact on academic performance was insignificant). As exhibited in the study of [79], the authors used the Monte Carlo and Bootstrap maximum likelihood approaches to assess the indirect impacts within 95% of the confidence level. As indicated in Table 3, a professor’s Pygmalion leadership (indirect coefficient = 0.067, p < 0.05) and charismatic leadership (indirect coefficient = 0.134, p < 0.01) would indirectly affect students’ academic performance through class engagement. Since the direct impacts of a professor’s two leadership styles on student academic performance were insignificant (i.e., Pygmalion leadership (critical ratio = 0.511) and charismatic leadership (critical ratio = 1.374)), class engagement played a role as a full mediator between a professor’s Pygmalion leadership/charismatic leadership and students’ academic performance.

5. Discussion

The academic performance of students is considered a core factor that determines their success for graduation and even after graduation (e.g., for job applications). In choosing to adopt favored leadership styles, faculty may enhance student academic performance [9]. Accordingly, this empirical study was conducted to predict academic performance from the perspectives of a professor on leadership styles in class. Due to the important role of a professor in leading a class throughout a semester, this study’s empirical findings verified that a professor’s leadership style could be a core attribute for student success and enhance academic performance. In particular, this study attempted to conceptually demonstrate and empirically examine the impact of a professor’s various leadership styles on student class engagement and academic performance. More specifically, the empirical results of this study were based on five leadership styes observed as predicting the engagement, trust, and performance of individuals in previous research.

According to [9], an individual’s leadership directs other people toward their goals (i.e., academic performance in this study) by guiding, structuring, and facilitating activities (i.e., class engagement in this study) and relationships with them (i.e., trust toward the professor in this study). Therefore, the empirical results of the current study proposed not only how to develop a professor’s leadership styles for student class engagement and trust toward the professor, but also how to enhance student academic performance in order to help them to succeed in the degree program. In sum, the main goal of the current empirical study was to reveal the critical roles of a professor’s leadership style regarding student academic achievement.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

One of the main contributions of this study to the extant literature is to theoretically formulate and empirically test a research model accounting for various aspects of a professor’s leadership style in the undergraduate student context. Specifically, prior research in the education field has considered the role of a professor’s leadership style as a core determinant of student perceptions of, attitudes toward, and behavior in class [9,12,80]. Whereas previous studies have focused primarily on the impact of one specific leadership style on student performance, in this study, we account for the possibility that professors may have used different types of leadership styles in class. For example, although two different professors may teach the same class with identical course content in one semester, students in each class tend to show different levels of class engagement and academic achievement, depending on how the professors lead the class with their unique leadership characteristics [9,15].

In the human resource management field, research has been conducted to explore various leadership styles and empirically investigate their distinct impact on followers’ favorable outcomes, such as trust, work engagement, and task performance. [16,81]. However, there is little research that proposes various leadership styles in addition to transformational and transactional leadership and investigates their distinct impact on students’ responses in the education setting. Our empirical study’s findings are based on the application of various leadership styles developed and studied in the human resource management field to the education setting to explore the most influential leadership styles that support students in achieving success. The empirical findings of this study enable scholars in the education field to apply more leadership-oriented models in the undergraduate student context to enhance student academic performance.

Second, this study applies and expands the social exchange theory to the education setting by proposing class engagement and trust toward a professor as mediators of the association between professor leadership styles and student academic performance. The theory assumes that individuals tend to seek to maximize benefits and minimize costs when involved in an exchange process [82]. Hence, when individual’s perceived expected benefits outweigh anticipated costs, they are more likely to be continuously involved in the exchange process [83]. The current study’s empirical finding is based on the notion that students also expect benefits from taking a class, and they calculate expected costs of money, time, and effort during a semester. Compared to the approach of prior research in the education field (i.e., viewing students as students of a professor only) [84,85], the current study also considers and treats students as customers of an educational service/product by focusing on the mediating roles of class engagement and trust toward a professor in improving academic performance. Some students may decide to withdraw from a class because of lower levels of benefits than they expected or because of higher levels of costs than they calculated. Consequently, this action may result in falling profits of academic institutions in the long-term.

The current study considers a professor’s leadership style as one of the most influential benefits that determines student engagement and trust toward the professor based on the social exchange theory. This is a different approach from those of prior research regarding the theory as well. For example, the study in [86] was based on the social exchange theory to predict knowledge sharing between students from individual motivations, such as economic reward and self-efficacy. Prior research has used the social exchange theory to build a strong relationship between students or between students and a university without consideration of the role of a professor in class [85,87]. However, the current research proposes a particular flow that indicates students should be engaged in class and trust their professor, which leads them to continue pursuing academic goals (i.e., academic performance). In other words, the primary focus of the social exchange theory in the education setting should not be the relationship between students but the relationship between a professor and students. Based on the social exchange theory, therefore, the current research suggests the underpinning flow that investigates the impact of distinct professor leadership styles on student perceptions of class engagement and trust in the professor to build a strong relationship between the professor’s students and class via the empirical results. Although the effect of trust in a professor on academic performance was not significant, the hypothesized research model was theoretically meaningful from the perspective of social exchange between a professor and students.

There may be potential factors that influence student academic performance in the education field, such as intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for learning, based on the self- determination theory [84]. However, it could be argued that the intrinsic motivations and characteristics are different for each student, and it is very challenging for professors to recognize and control those variable motivations and characteristics in class. To better understand students’ favorable perceptions, attitudes, and behavior in class, this study focused on the perspectives of a professor on leadership styles and how this has a positive effect on students based on the social exchange theory. This study recommends that scholars recognize the importance of a professor’s leadership style in enhancing student academic performance as well as class engagement compared to prior empirical studies’ approaches to student-related factors, learning motivation, demographic characteristics, and personality [88,89].

5.2. Practical Implications

It has been theorized that leadership, leadership styles, and skills can be taught. A leadership style consists of several characteristics. Students appear to respond favorably to characteristics that instill trust and promote engagement. We encourage professors to adopt hybrid leadership characteristics from more than one leadership style when the student composition supports it. Universities could assist by providing workshops for professors on leadership skills (e.g., charismatic and emotional leadership skills) after conducting a needs assessment to identify which leadership style characteristics professors do and do not have. Professor leadership styles can be assessed from student evaluation forms and qualitative feedback (e.g., creating a word cloud or word tree associated with the professors’ characteristics) and/or through discussions with their mentors or department chairs. Universities can promote a variety of techniques to help professors develop characteristics of effective leadership. Seminars, workshops, teacher training, brown bag luncheons, etc. can provide important tools.

For workshops focused on charismatic leadership, the most influential leadership style in this study, universities and each department should provide professors with information on how to develop attributes of effectiveness and charisma by articulating their visions for students. More specifically, professors in these workshops can practice developing and displaying charismatic styles of speech and delivery through simulated lecture sessions. This would allow professors to gain skills in establishing a charismatic image for students. For Pygmalion leadership style workshops, professors should discuss how to establish a high expectation for each student, set difficult and specific goals, and provide more challenging opportunities and authentic feedback to students.

Workshops on emotional leadership should help develop professors’ emotional and subjective aspects when interacting with students. Compared to the charismatic leadership style, professors would learn about how to empathize with students’ emotional states via various cases and simulations. Finally, workshops related to transformational leadership style should support faculty sharing their class-related visions and goals with their students through case discussions and simulations with other professors. One method of doing so might be providing professors with the opportunity to have in-person meetings with transformational leaders from academia or industry, which may inspire them to talk optimistically about their plans and insights for students and classes.

5.3. Limitations

As with other social science studies, this research has limitations and provides directions for future studies in the education field. First, this research provides a controlled model to initially test multiple leadership styles concurrently. As in any complex quantitative model, it is impractical to explore all potential pathways. We hope this research inspires scholars to engage in future studies that expand the depth and breadth of research exploring leadership in an educational context. Additionally, we are hopeful that the validation of this model may provide a platform for future research that can broaden the respondent pool without the strict controls in place in this study. Specifically, future research should explore additional pathways, cause and effect, and interaction effects. Second, the empirical findings of this study may only be generalizable to the undergraduate programs in the United States, because the participants in this study were limited to US students. Future research could be expanded to other geographic regions. Third, although the measurement model of this study confirmed reliability and validity, the empirical findings and implications relied heavily on the cross-sectional approach. Thus, future research might employ longitudinal approaches. Fourth, this study considered five leadership styles to prevent participants’ fatigue while completing the survey. Future studies might explore other leadership styles. Fifth, this study focused on a student thinking about their best classroom experience. However, prompting a student with their favorite professor may have limited the generalizability of the results. Future studies should look at both positive and negative classroom experiences in an evaluation of professor leadership styles. Finally, though a major contribution of this study is the examination of leadership styles concurrently in an education application, this limits the breadth of the model. We think that future research should consider the expansion of this model to include additional variables such as student focus, active learning strategies, etc. [90].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., N.D.A., T.L.K.; methodology, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, N.D.A., T.L.K.; visualization, M.K., N.D.A., T.L.K.; project administration, M.K., N.D.A., T.L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Louisiana State University in Shreveport (LSUS 2019-00031 and 25 February 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions e.g., privacy or ethical.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Farrington, R. Is college even worth it? Here’s how to decide. Forbes 2022, 17, e10255. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertfarrington/2022/01/11/is-college-even-worth-it-heres-how-to-decide/?sh=76956353461f (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. 2022. Available online: https://nscresearchcenter.org/stay-informed/ (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Kovacs, K. The Pandemic’s Impact on College Enrollment. 2022. Available online: https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/covid19-impact-on-college-enrollment/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20National%20Student,fell%204.4%25%20in%20the%20fall (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Conley, B.; Massa, R. The Great Interruption. 2022. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/views/2022/02/28/enrollment-changes-colleges-are-feeling-are-much-more-covid-19 (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Dickler, J. Universities Are Going to Continue to Suffer. Some Colleges Struggle with Enrollment Declines, Underfunding. CNBC. 2022. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/10/05/colleges-struggle-with-enrollment-declines-underfunding-post-covid.html (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Staff Writers. The 12 Biggest Reasons for Transferring Colleges. Best Colleges. 2022. Available online: https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/top-reasons-students-transfer-colleges/#:~:text=Over%20one%2Dthird%20of%20students,%2D19%2C%20and%20school%20fit (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Moldoff, D.K. 10 Reasons Why Students Transfer. Academy One. 2022. Available online: https://www.collegetransfer.net/Articles/I-Am-Looking-to-Transfer-Colleges/10-Reasons-Why-Students-Transfer (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. 2016. Available online: https://nscresearchcenter.org/category/2016/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Balwant, P.T.; Birdi, K.; Stephan, U.; Topakas, A. Transformational instructor- leadership and academic performance: A moderated mediation model of student engagement and structural distance. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 884–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fraihat, D.; Joy, M.; Sinclair, J. Evaluating E-learning systems success: An empirical study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandmiller, C.; Dumont, H.; Becker, M. Teacher Perceptions of Learning Motivation and Classroom Behavior: The Role of Student Characteristics. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 63, 101893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarivirta, T.; Kumpulainen, K. School autonomy, leadership and student achievement: Reflections from Finland. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yough, M.; Merzdorf, H.E.; Fedesco, H.N.; Cho, H.J. Flipping the classroom in teacher education: Implications for motivation and learning. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noell, G.H.; Burns, J.M.; Gansle, K.A. Linking student achievement to teacher preparation: Emergent challenges in implementing value added assessment. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. Covert communication in classrooms, clinics, courtrooms, and cubicles. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, S.H.; Koo, D.W.; Cannon, D.F. Pygmalion leadership: Theory and application to the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 20, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, B.; Junni, P. CEO transformational and transactional leadership and organizational innovation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 1542–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, A. Investigation of transformational and transactional leadership styles of school principals, and evaluation of them in terms of educational administration. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 10, 2758–2767. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y. Emotional leadership as a key dimension of public relations leadership: A national survey of public relations leaders. J. Public Relat. Res. 2010, 22, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkan, S.; Goodboy, A.K. Transformational leadership in the classroom: Fostering student learning, student participation, and teacher credibility. J. Instr. Psychol. 2009, 36, 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Pounder, J.S. Transformational classroom leadership: A basis for academic staff development. J. Manag. Dev. 2009, 28, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Barsade, S.G. Mood and emotions in small groups and work teams. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuijen, X.M.; van den Berg, P.T.; van Dam, K.; Thierry, H. Pygmalion and employee learning: The role of leader behaviors. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1248–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Engemann, K.N.; Williams, C.E.; Gooty, J.; McCauley, K.D.; Medaugh, M.R. A meta-analytic review and future research agenda of charismatic leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 508–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkan, S.; Goodboy, A.K. Transformational leadership in the classroom: The development and validation of the Student Intellectual Stimulation Scale. Commun. Rep. 2010, 23, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkan, S.; Goodboy, A.K. Leadership in the college classroom: The use of charismatic leadership as a deterrent to student resistance strategies. J. Classr. Interact. 2011, 46, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; Matute, J. Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojode, L.A.; Walumbwa, O.; Kuchinke, P. Developing human capital for the evolving work environment: Transactional and transformational leadership within instructional setting. In Proceedings of the Midwest Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 6–11 August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pounder, J.S. Transformational classroom leadership: The fourth wave of teacher leadership? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2006, 34, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounder, J.S. Transformational leadership: Practicing what we teach in the management classroom. J. Educ. Bus. 2008, 84, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, H.H.M.; Huang, X.; Lam, W. Why does transformational leadership matter for employee turnover? A multi-foci social exchange perspective. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyong, D.N.; Rathee, N.K. Exploring emotional intelligence and authentic leadership in relation to academic achievement among nursing students. Int. J. Arts Sci. 2017, 10, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, R.H. The many faces of emotional leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.S.; Law, K.S. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirayath, S.; Lalgem, E.M.; George, S.B. Expectations come true: A study of Pygmalion effect on the performance of employees. Manag. Labour Stud. 2009, 34, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Mind Garden: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Jung, D.I.; Berson, Y. Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J.A.; Kanungo, R.N.; Menon, S.T. Charismatic leadership and follower effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.L.; Steers, R.M.; Terborg, J.R. The effects of transformational leadership on teacher attitudes and student performance in Singapore. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, L. Teacher development through reflective teaching. In Second Language Teacher Education; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Sitkin, S.B. A critical assessment of charismatic—Transformational leadership research: Back to the drawing board? Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovica, D.; Ciricb, M. Benefits of transformational leadership in the context of education. Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. EpSBS 2016, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.L. Instructor transformational leadership and student outcomes. Emerg. Leadersh. Journeys 2011, 4, 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Pounder, J.S.; Stoffell, P.; Choi, E. Transformational classroom leadership and workplace engagement: Is there a relationship? Qual. Assur. Educ. Int. Perspect. 2018, 26, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simola, S.; Barling, J.; Turner, N. Transformational leadership and leaders’ mode of care reasoning. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. A review of transformational school leadership research 1996–2005. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2005, 4, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, D. Leadership and expectations: Pygmalion effects and other self-fulfilling prophecies in organizations. Leadersh. Q. 1992, 3, 271–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Sharma, K. Self-fulfilling prophecy: A literature review. Int. J. Interdiscip. Multidiscip. Stud. 2015, 2, 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. The Pygmalion process and employee creativity. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Bastardoz, N.; Jacquart, P.; Shamir, B. Charisma: An ill-defined and ill- measured gift. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabo, A.; Van Vugt, M. Charismatic leadership and the evolution of cooperation. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2016, 37, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezar, A.J.; Kinzie, J. Examining the ways institutions create student engagement: The role of mission. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2006, 47, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.R. Framing student engagement in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, G.F.; Burch, J.J.; Womble, J. Student engagement: An empirical analysis of the effects of implementing mandatory web-based learning systems. Organ. Manag. J. 2017, 14, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S.P. Trust and commitment influences on customer retention: Insights from business-to-business services. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Chen, W.; Duanmu, J.L. Determinants of international students’ academic performance: A comparison between Chinese and other international students. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2010, 14, 389–405. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott-Chapman, J.; Hughes, P.; Wyld, C. Monitoring Student Progress: A Framework for Improving Student Performance and Reducing Attrition in Higher Education; National Clearinghouse for Youth Studies: Hobart, Tasmania, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J.B. Student Approaches to Learning and Studying: Research Monograph; Australian Council for Educational Research Ltd., Radford House, Frederick St.: Hawthorn, Australia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, A.; Boyle, E.; Dunleavy, K.; Ferguson, J. The relationship between personality, approach to learning and academic performance. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1907–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Cropanzano, R.; Hartnell, C.A. Organizational justice, voluntary learning behavior, and job performance: A test of the mediating effects of identification and leader-member exchange. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1103–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Yoo, C.Y. Branded app usability: Conceptualization, measurement, and prediction of consumer loyalty. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Assessing method variance in multitrait-multimethod matrices: The case of self-reported affect and perceptions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Assumption and comparative strengths of the two- step approach: Comment on Fornell and Yi. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 20, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, R.T.; Moorman, C.; Dickson, P.R. Getting return on quality: Revenue expansion, cost reduction, or both? J. Mark. 2002, 66, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Koo, D.W.; Han, H.S. Innovative behavior motivations among frontline employees: The mediating role of knowledge management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. How does a celebrity make fans happy? Interaction between celebrities and fans in the social media context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balwant, P.T. Transformational instructor-leadership in higher education teaching: A meta-analytic review and research agenda. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2016, 9, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.C.; Idris, M.A.; Tuckey, M. Supervisory coaching and performance feedback as mediators of the relationships between leadership styles, work engagement, and turnover intention. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2019, 22, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms; Harcourt Brace Javanovich: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.S.; Koo, D.W. Linking LMX, engagement, innovative behavior, and job performance in hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3044–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A. Supportive Chinese supervisor, innovative international students: A social exchange theory perspective. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, P.; Prince, N. The psychological contract of science students: Social exchange with universities and university staff from the students’ perspective. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2015, 34, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lytras, M.; Ordonez de Pablos, P.; He, W. Exploring the effect of transformational leadership on individual creativity in e-learning: A perspective of social exchange theory. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Zhang, M.; Qi, D. Effects of different interactions on students’ sense of community in e-learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2017, 115, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Boucher, A.R. Optimizing the power of choice: Supporting student autonomy to foster motivation and engagement in learning. Mind Brain Educ. 2015, 9, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhija, A.; Richards, D.; de Haan, J.; Dignum, F.; Jacobson, M.J. The influence of gender, personality, cognitive and affective student engagement on academic engagement in educational virtual worlds. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, Proceedings of the 19th International Conference, AIED 2018, London, UK, 27–30 June 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Nepal, R.; Rogerson, A.M. From theory to practice of promoting student engagement in business and law-related disciplines: The case of undergraduate economics education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).