A Systematic Review of Critical Success Factors in Blended Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

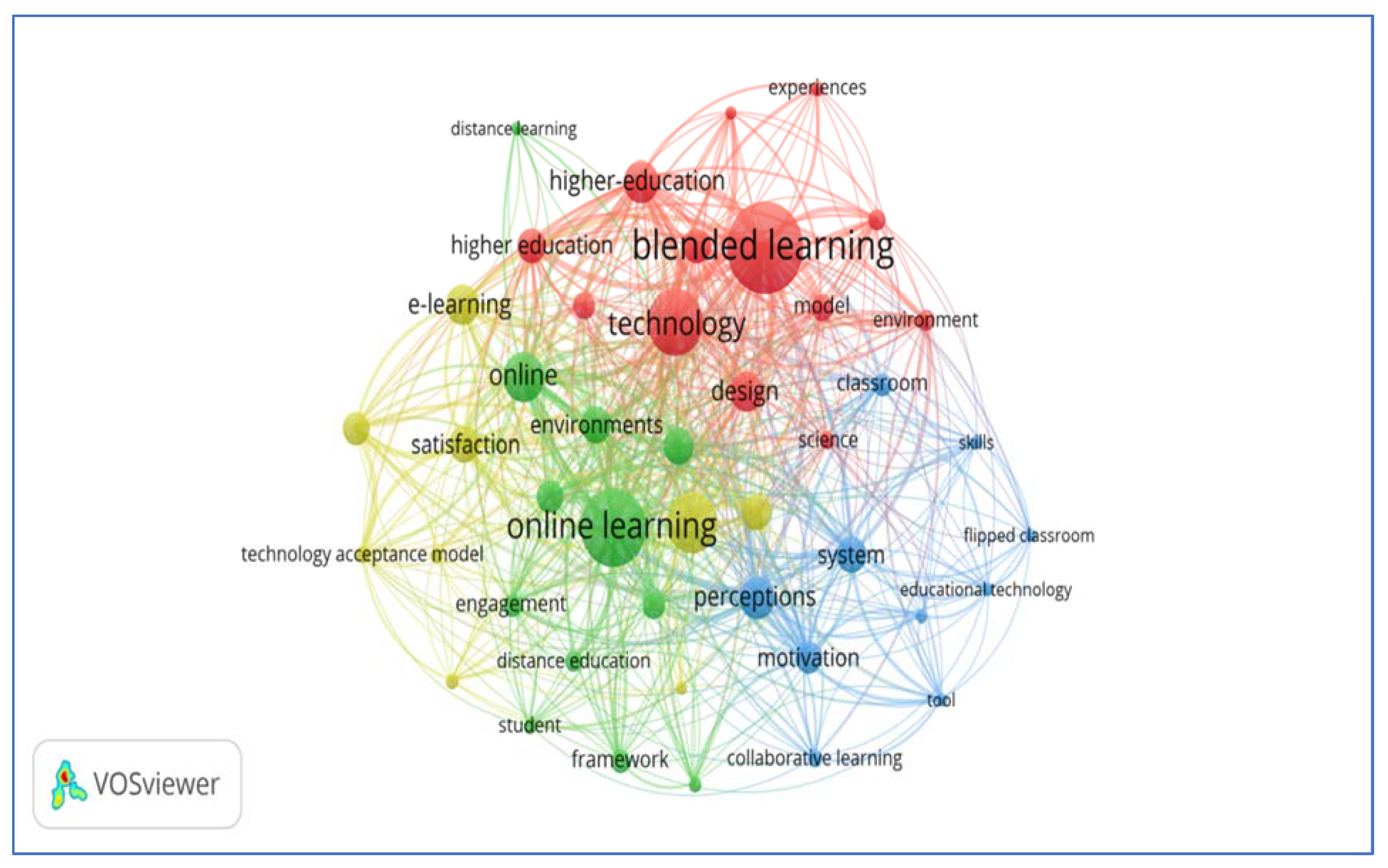

2. Literature Review

2.1. Blended Learning

2.2. Satisfaction in Blended Learning

2.3. Performance in Blended Learning

2.4. Critical Success Factors

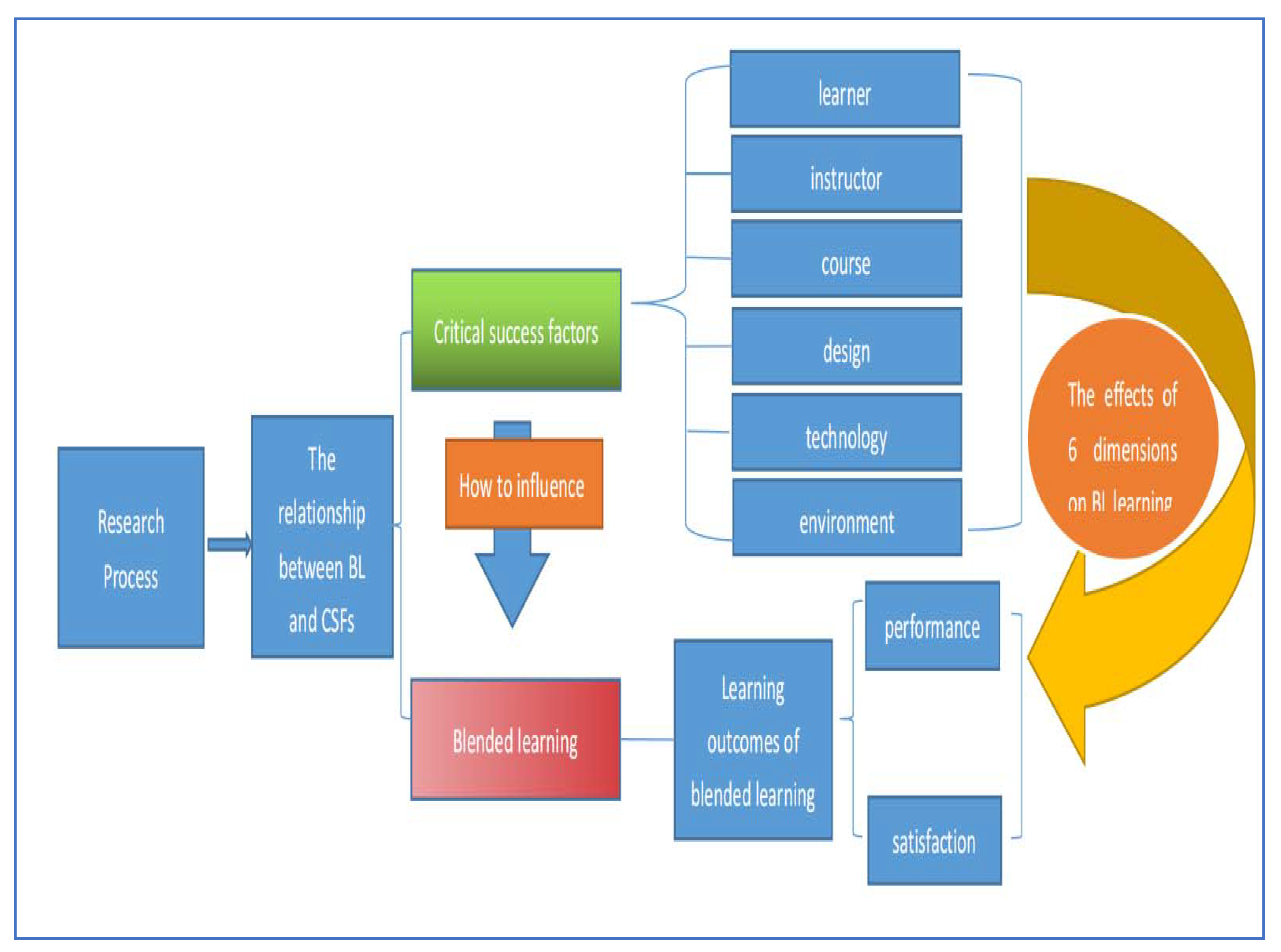

2.5. Purposed and Research Questions

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Designs

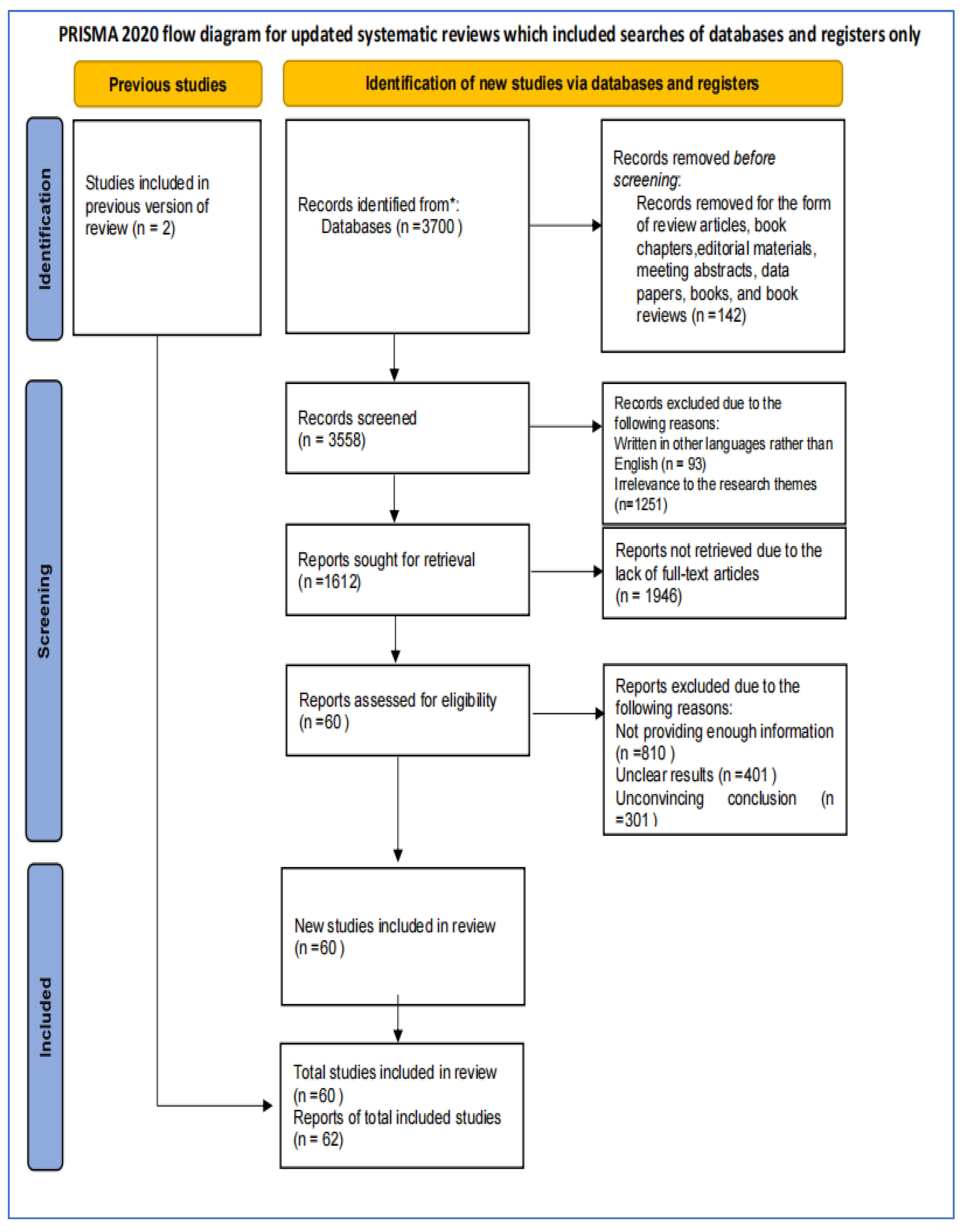

3.2. Research Corpus

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.4. Study Selection

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghazal, S.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Aldowah, H. “I am Still Learning”: Modeling LMS Critical Success Factors for Promoting Students’ Experience and Satisfaction in a Blended Learning Environment. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 77179–77201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, C.; Donalds, C.; Osei-Bryson, K.-M. Investigating critical success factors in online learning environments in higher education systems in the Caribbean. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2018, 24, 582–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkis, N.; Temizel, T.T. The Impact of Motivation and Personality on Academic Performance in Online and Blended Learning Environments. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2018, 21, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, A.Y.; Rajkhan, A.A. E-Learning Critical Success Factors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Analysis of E-Learning Managerial Perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.M.Y.; Geng, S.; Li, T. Student enrollment, motivation and learning performance in a blended learning environment: The mediating effects of social, teaching, and cognitive presence. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuban, C.D.; Hartman, J.L.; Moskal, P.D. Blended learning. Educause Cent. Appl. Res. Bull. 2004, 7, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.S.; Yao, A.Y.T. An Empirical Evaluation of Critical Factors Influencing Learner Satisfaction in Blended Learning: A Pilot Study. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 1667–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, A.; Rooney, D.; Lizier, A.L. Using technology integration frameworks in vocational education and training. Int. J. Train. Res. 2021, 19, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.; Ward, R. Developing a general extended technology acceptance model for e-learning (GETAMEL) by analysing commonly used external factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 56, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kong, S.C. Affordances and constraints of BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) for learning and teaching in higher education: Teachers’ perspectives. Internet High. Educ. 2017, 32, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, M.S.; Vallerand, R.J.; Guay, F. Academic motivation and school performance: Toward a structural model. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 20, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B.; Kamaludin, A.; Romli, A.; Raffei, A.F.M.; Phon, D.N.A.E.; Abdullah, A.; Ming, G.L. Blended Learning Adoption and Implementation in Higher Education: A Theoretical and Systematic Review. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2022, 27, 531–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, R.; Wu, J. A Literature Review on Blended Learning: Based on Analytical Framework of Blended Learning. J. Distance Educ. 2018, 36, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Sizing the Opportunity: The Quality and Extent of Online Education in the United States, 2002 and 2003. Sloan Consort. 2003, 659–673. [Google Scholar]

- Bliuc, A.M.; Goodyear, P.; Ellis, R.A. Research Focus and Methodological Choices in Studies into Students’ Experiences of Blended Learning in Higher Education. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 4, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasoh, F. Exploring the roles of blended learning as an approach to improve teaching and learning English. In Proceedings of the Multidisciplinary Academic Conference 2016, Albena, Bulgaria, 24–30 August 2016; pp. 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.R.; Woodfield, W.; Harrison, B. A framework for institutional adoption and implementation of blended learning in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 18, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, W.; Sukjairungwattana, P. Meta-analyses of differences in blended and traditional learning outcomes and students’ attitudes. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 926947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halverson, L.R.; Graham, C.R.; Spring, K.J.; Drysdale, J.S.; Henrie, C.R. A thematic analysis of the most highly cited scholarship in the first decade of blended learning research. Internet High. Educ. 2014, 20, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tennyson, R.D.; Hsia, T.L. A study of student satisfaction in a blended e-learning system environment. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Kanuka, H. Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.; Vaughan, N.D. Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles and Guidelines; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, E. A Blended Learning Model in Higher Education: A Comparative Study of Blended Learning in UK and Malaysia. Unpublished Thesis, University of Glamorgan, Wales, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Diep, A.N.; Zhu, C.; Struyven, K.; Blieck, Y. Who or what contributes to student satisfaction in different blended learning modalities? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.M.; Lin, G.Y.; Laffey, J.M. Building A Social and Motivational Framework For Understanding Satisfaction In Online Learning. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2008, 38, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.C. How student satisfaction factors affect perceived learning. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2010, 10, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.G.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, W. Student satisfaction, learning outcomes, and cognitive loads with a mobile learning platform. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.C.; Tsai, R.J.; Finger, G.; Chen, Y.Y.; Yeh, D. What drives a successful e-learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction. Comput. Educ. 2008, 50, 1183–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Gonzaga, E.; Ramirez-Arellano, A. The Influence of Motivation, Emotions, Cognition, and Metacognition on Students’ Learning Performance: A Comparative Study in Higher Education in Blended and Traditional Contexts. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211027561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, Q.N.; Muhammad, A.; Sanober, S.; Qureshi, M.R.N.; Shah, A. A mixed method study for investigating critical success factors (CSFs) of e-learning in Saudi Arabian universities. Methods 2017, 8, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Otter, R.R.; Seipel, S.; Graeff, T.; Alexander, B.; Boraiko, C.; Gray, J.; Petersen, K.; Sadler, K. Comparing student and faculty perceptions of online and traditional courses. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 19, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidecker, J.K.; Bruno, A.V. Identifying and using critical success factors. Long Range Plan. 1984, 17, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.J.; Huang, W.-H.; Lee, D.Y. The impact of employee’s perception of organizational climate on their technology acceptance toward e-learning in South Korea. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. Int. J. 2012, 4, 359–378. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, M.A.; Nunes, J.M. Critical issues for e-learning delivery: What may seem obvious is not always put into practice. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2008, 24, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; Lim, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Investigating the structural relationships among organisational support, learning flow, learners’ satisfaction and learning transfer in corporate e-learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 42, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.; Kellermanns, F.W. Student acceptance of a web-based course management system. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2004, 3, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, H.M. An empirical investigation of student acceptance of course websites. Comput. Educ. 2003, 40, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.-S.; Lai, J.-Y.; Wang, Y.-S. Factors affecting engineers’ acceptance of asynchronous e-learning systems in high-tech companies. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, H.M. Critical success factors for E-learning acceptance: Confirmatory factor models. Comput. Educ. 2007, 49, 396–413. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, D. Improved training methods through the use of multimedia technology. J. Comp. Inf. Syst. 1999, 40, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Gawad, T.; Woollard, J. Critical success factors for implementing classless e-learning systems in the Egyptian higher education. Int. J. Instr. Technol. Distance Learn. 2015, 12, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Alhabeeb, A.; Rowley, J. E-learning critical success factors: Comparing perspectives from academic staff and students. Comput. Educ. 2018, 127, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C.; Boyd, C.; Jain, S.; Khorsan, R.; Jonas, W. Rapid evidence assessment of the literature (REAL): Streamlining the systematic review process and creating utility for evidence-based health care. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.G.; Xu, W.; Yu, L. Constructing an online sustainable educational model in the COVID-19 pandemic environments. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-T.; Hajiyev, J.; Su, C.-R. Examining the students’ behavioral intention to use E-learning in Azerbaijan? The general extended technology acceptance model for E-learning approach. Comput. Educ. 2017, 111, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S.-S.; Huang, H.-M.; Chen, G.-D. Surveying instructor and learner attitudes toward E-learning. Comput. Educ. 2007, 49, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, E.M.; Dawson, H. Learning with motivation. In Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction; Mayer, R.E., Alexander, P.A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.C. The role of perceived resources in online learning adoption. Comput. Educ. 2008, 50, 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, N.J.; Peterson, E.R. Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: Relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2004, 41, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Hackley, P. Teaching effectiveness in technology mediated distance learning. Acad. Manage. J. 1997, 40, 1282–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.M.; Halpin, R. Teachers’ attitudes and use of multimedia technology in the classroom: Constructivist-based professional development training for school districts. J. Computer. Teacher Educ. 2002, 18, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, H.; Rada, R. Understanding the influence of perceived usability and technology self-efficacy on teachers. J. Res. Technol. Educ. Technol. 2011, 43, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Y.; Ramim, M.M. The E-learning skills gap study: Initial results of skills desired for persistence and success in online engineering and computing courses. In Proceeding of the Chais 2017 Conference on Innovative and Learning Technologies Research, Bologna, Italy, 26 June–1 July 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, S.; Koseler, R. Multi-dimensional students’ evaluation of e-learning systems in the higher education context: An empirical investigation. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbaugh, J.B.; Duray, R. Class section size, perceived classroom characteristics, instructor experience, and student learning and satisfaction with web-based courses: A study and comparison of two online MBA programs. In Academy of Management Best Papers Proceedings (pp. A1–A6) [CD-ROM]; Nagao, D., Ed.; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- De-Marcos, L.; García-Cabo, A.; López, E.G. Towards the Social Gamification of e-Learning: A Practical Experiment. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 33, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Baragash, R.S.; Al-Samarraie, H. Blended learning: Investigating the influence of engagement in multiple learning delivery modes on students’ performance. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 2082–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwalumbwe, I.; Mtebe, J.S. Using Learning Analytics to Predict Students’ Performance In Moodle Learning Management System: A Case Of Mbeya University Of Science And Technology. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2017, 79, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.M.; Zhu, C.; Diep, N.A. The effect of blended learning on student performance at course-level in higher education: A meta-analysis. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2017, 53, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini, R.; Sehgal, S.; Agrawal, G. Todays’ digital natives: An exploratory study on students’ engagement and satisfaction towards virtual classes amid COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2021, 38, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.; Shen, P.; Tsai, M. Developing an appropriate design of blended learning with web-enabled self-regulated learning to enhance students’ learning and thoughts regarding online learning. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2011, 30, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korr, J.; Derwin, E.B.; Greene, K.; Sokoloff, W. Transitioning an adult serving university to a blended learning model. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2012, 60, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Y.; Yu, H.J. Effectiveness study of English learning in blended learning environment. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2012, 2, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsowat, H. An EFL flipped classroom teaching model: Effects on English language higher-order thinking skills, student engagement and satisfaction. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Peng, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, H. Differentiating the learning styles of college students in different disciplines in a college English blended learning setting. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappamihiel, N.E. English as a second language students and English language anxiety: Issues in the mainstream classroom. Res. Teach. Engl. 2002, 36, 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, Z.; Rokhman, F.; Mathrani, A. Exploring the influencing factors of learning management systems continuance intention in a blended learning environment. Int. J. Innov. Learn. 2021, 30, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, M.; Bacao, F.; Oliveira, T. An e-learning theoretical framework. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 292. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, M.; Hwang, Y. Predicting the use of web-based information systems: Self-efficacy, enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies | Study Dimensions | Findings | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | 1 dimension (technology) | satisfaction | Blended learning |

| [3] | 1 dimension (learner) | Satisfaction and performance | Online and blended learning |

| [7] | 1 dimension (design) | performance | Blended learning |

| [8] | 1 dimension (technology) | performance | IT technologies in the process of gradual study |

| [3,9] | 1 dimension (environment) | Performance and engagement | traditional offline courses, the online film clip |

| [10] | 1 dimension (course) | Performance | Blended learning |

| [11] | 3 dimensions (learner, instructor, technology) | perception | Online learning |

| The current study | All dimensions included in selected studies | Performance, satisfaction | Blended learning |

| Factors | Prior Research | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| learner | [9,10,36,37,38] | It mainly focuses on learner characteristics such as learning speed, interest, attitude, motivation, cognition, use of computer systems, computer efficiency and experience, and demographic characteristics. |

| instructor | [31,33,39] | It mainly focuses on the instructor’s teaching qualities, such as attitude, flexibility, responsiveness, knowledge of computer systems, teaching style and effectiveness. |

| course | [30,40,41,42] | It mainly focuses on course material and purpose, including course design, assessment, grading, quality of content, and flexibility. |

| design | [30,41,42] | It mainly focuses on instructional characteristics to align with the objectives of the institution, which include the clarity of the objective, teaching methods, learning strategies and psychology, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of conducting. |

| technology | [30,41,42] | It mainly focuses on the ICT system to present learning resources and purpose, which include ease of use, quality, reliability, efficiency, privacy, information, and the use of the software. |

| environment | [30,41,42] | It mainly refers to the learning environment, including learning management systems, technological infrastructure, interactivity, variety of assessments, system accessibility, and ease of navigation and other facilitating conditions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Min, W.; Yu, Z. A Systematic Review of Critical Success Factors in Blended Learning. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050469

Min W, Yu Z. A Systematic Review of Critical Success Factors in Blended Learning. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(5):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050469

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Wenhe, and Zhonggen Yu. 2023. "A Systematic Review of Critical Success Factors in Blended Learning" Education Sciences 13, no. 5: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050469

APA StyleMin, W., & Yu, Z. (2023). A Systematic Review of Critical Success Factors in Blended Learning. Education Sciences, 13(5), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050469