Employing a Force and Motion Learning Progression to Investigate the Relationship between Task Characteristics and Students’ Conceptions at Different Levels of Sophistication

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background and State of Research

1.1.1. Conceptual Change and Learning Progressions

- no clear distinction between force and motion (force = motion),

- force is proportional to motion (force~motion),

- force is proportional to velocity (force~velocity),

- force is proportional to acceleration (force~acceleration).

1.1.2. Variability of Students’ Conceptions

1.2. Effects of Conceptual and Contextual Task Characteristics: Focus of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrument

2.1.1. Selection of Conceptual and Contextual Task Characteristics

- 1.

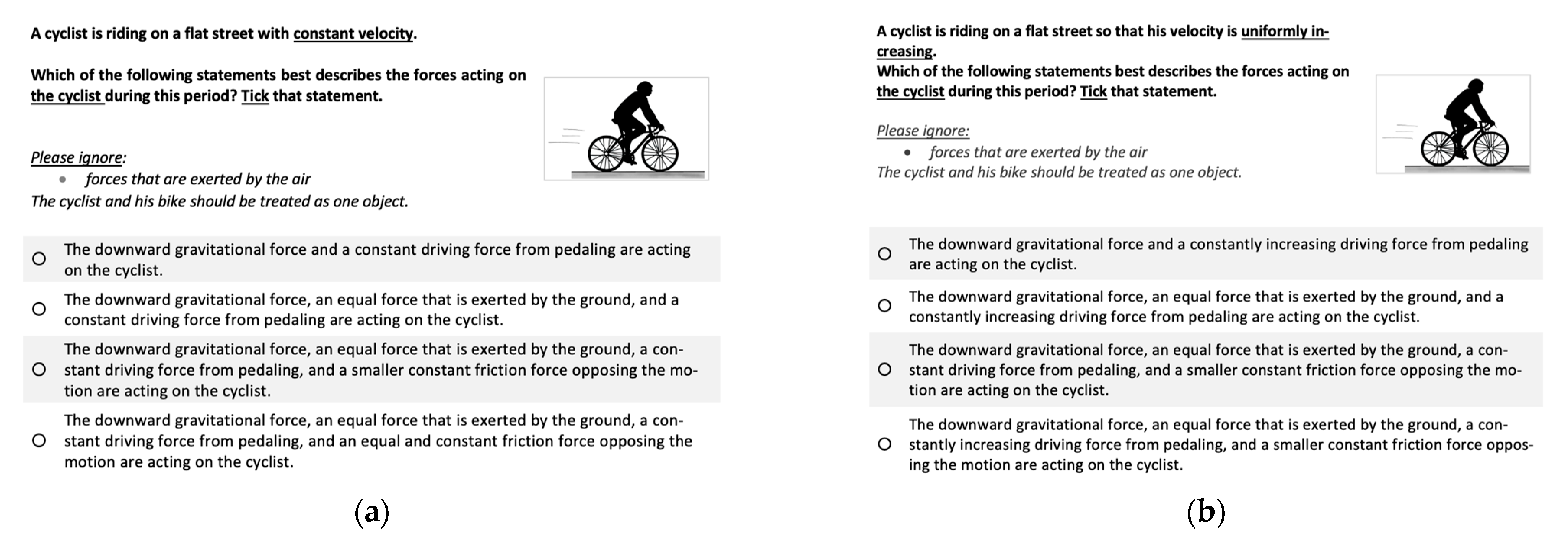

- The Newtonian law, that is, whether an item addresses the 1st or 2nd law (see Figure 1 for a pair of items differing in the addressed law).

- 2.

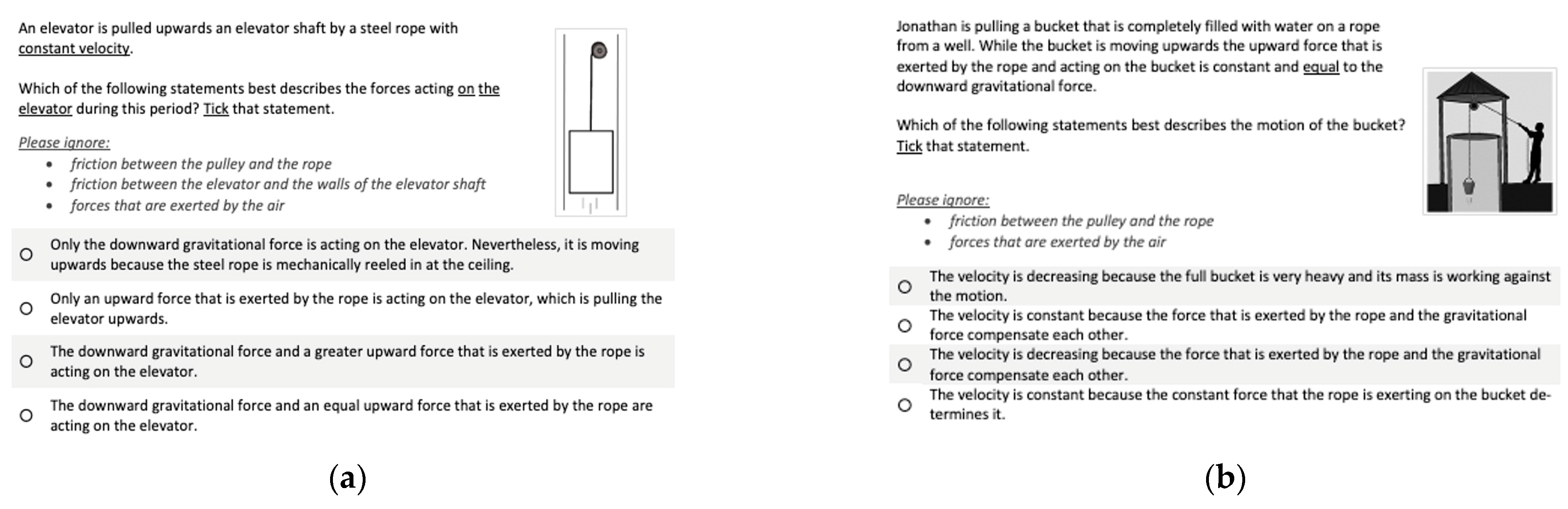

- The direction of problem, that is, whether students have to reason from given forces to resulting motion (force → motion) or from given motion to acting forces (motion → force; see Figure 2 for a pair of items differing in the direction of problem).

- 3.

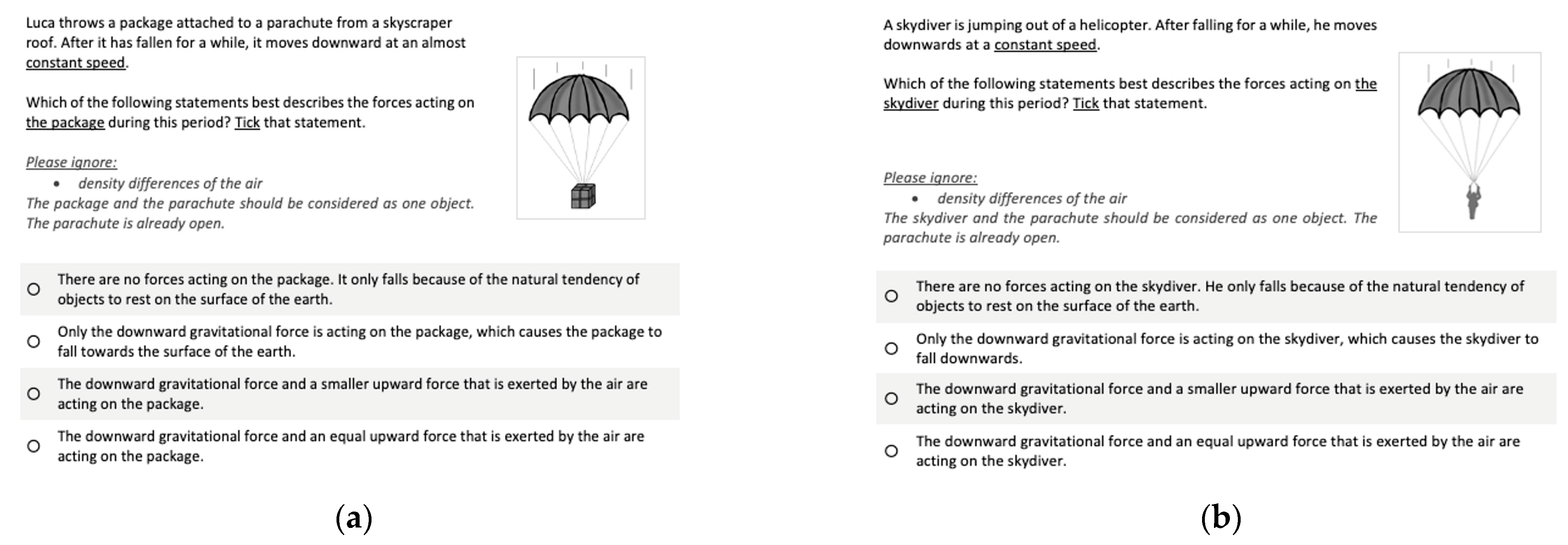

- The plane of motion, describing if an item addresses either horizontal or vertical motion (see Figure 3 for a pair of items differing in the plane of motion).

- 4.

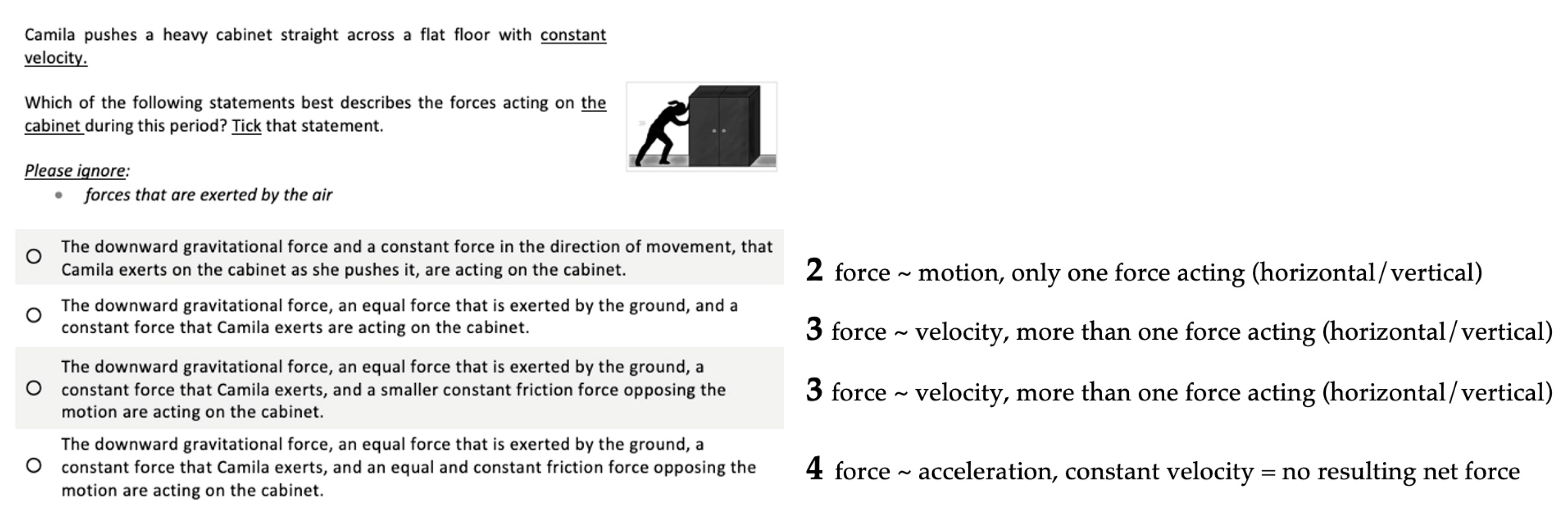

- The type of object considered, describing if an item addresses either a non-living object or a person (see Figure 4 for a pair of items differing in the type of object considered).

2.1.2. Development and Compilation of Items and Test Booklets

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Step 1: Data Entry and Rasch Modeling of Raw Scores

- Model 1: All items are assumed to define one single trait.

- Model 2a: Items on Newton’s 1st and 2nd law define one trait, items on Newton’s 3rd law another.

- Model 2b: Items on Newton’s 1st and 3rd law define one trait, items on Newton’s 2nd law another.

- Model 2c: Items on Newton’s 1st law define one trait, items on Newton’s 2nd and 3rd law another.

- Model 3: Items on Newton’s 1st, 2nd, and 3rd law define three separate traits.

2.3.2. Step 2: Investigation of Instrument Functioning

2.3.3. Step 3: Estimation of Item Difficulty

- 2: the probability of choosing an answer on level 2 or higher is equal to the probability of choosing an answer on level 1.

- 3: the probability of choosing an answer on level 3 or higher is equal to the probability of choosing an answer on a lower level (i.e., 2 or 1).

- 4: the probability of choosing an answer on level 4 is equal to the probability of choosing an answer on a lower level (i.e., 3, 2, or 1).

2.3.4. Step 4: Investigating Effects of CCTCs Using Multiple Regression

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Newton’s Laws (Conceptual)

4.2. Effects of the Direction of Problem (Conceptual)

4.3. Effects of the Plane of Motion (Contextual)

4.4. Effects of the Type of Object (Contextual)

4.5. General Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bao, L.; Redish, E.F. Educational Assessment and Underlying Models of Cognition. In The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: The Contributions of Research Universities; Becker, W.E., Andrews, M.L., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2004; pp. 221–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.; Lemmer, M.; Gunstone, R. Alternative conceptions: Turning adversity into advantage. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schecker, H.; Duit, R. Schülervorstellungen und Physiklernen [Students’ conceptions and physics learning]. In Schülervorstellungen und Physikunterricht; Ein Lehrbuch für Studium, Referendariat und Unterrichtspraxis [Students’ Conceptions and Physics Learning. A Textbook for Studies, Teacher Training and Practice]; Schecker, H., Wilhelm, T., Hopf, M., Duit, R., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.; Jones, G.; Hurford, W. Children’s conceptual understanding of forces and equilibrium. Phys. Educ. 1985, 20, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausubel, D.P. Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo, A.C.; von Aufschnaiter, C. Moving beyond misconceptions: Learning progressions as a lens for seeing progress in student thinking. Phys. Teach. 2018, 56, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSessa, A.A. A History of Conceptual Change Research: Threads and Fault Lines. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, 2nd ed.; Sawyer, R., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, M.; Wilhelm, T. Conceptual Change—Entwicklung physikalischer Vorstellungen [Conceptual Change—development of physics conceptions]. In Schülervorstellungen und Physikunterricht; Ein Lehrbuch für Studium, Referendariat und Unterrichtspraxis [Students’ Conceptions and Physics Learning. A Textbook for Studies, Teacher Training and Practice; Schecker, H., Wilhelm, T., Hopf, M., Duit, R., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedderer, H.; Schecker, H. Towards an Explicit Description of Cognitive Systems for Research in Physics Learning. In Research in Physics Learning. Theoretical Issues and Empirical Studies; Duit, R., Goldberg, F., Niedderer, H., Eds.; IPN: Kiel, Germany, 1992; pp. 74–98. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society; Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Duit, R.; Treagust, D.F. Learning in Science—From Behaviourism towards Social Constructivism and Beyond. In International Handbook of Science Education; Fraser, B.J., Tobin, K.G., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School, Expanded Edition; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duit, R.; Bibliography—STCSE. Students’ and Teachers’ Conceptions and Science Education. 2009. Available online: https://archiv.ipn.uni-kiel.de/stcse/ (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Schecker, H.; Wilhelm, T. Schülervorstellungen in der Mechanik [Students’ conceptions in mechanics]. In Schülervorstellungen und Physikunterricht, Ein Lehrbuch für Studium, Referendariat und Unterrichtspraxis [Students’ Conceptions and Physics Learning. A Textbook for Studies, Teacher Training and Practice]; Schecker, H., Wilhelm, T., Hopf, M., Duit, R., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.E.; Hammer, D. Conceptual Change in Physics. In International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change; Vosniadou, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo, A.C.; Steedle, J.T. Developing and assessing a force and motion learning progression. Sci. Educ. 2009, 93, 389–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, A.C. Learning progressions: Significant promise, significant change. Z. für Erzieh. 2012, 15, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Taking Science to School: Learning and Teaching Science in Grades K-8; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmer, M. Nature, cause and effect of students’ intuitive conceptions regarding changes in velocity. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minstrell, J. Facets of Students’ Knowledge and Relevant Instruction. In Research in Physics Learning. Theoretical Issues and Empirical Studies; Duit, R., Goldberg, F., Niedderer, H., Eds.; IPN: Kiel, Germany, 1992; pp. 110–128. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, D. The effect of context on students’ reasoning about forces. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1997, 19, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Aufschnaiter, C.; Rogge, C. Conceptual change in learning. In Encyclopedia of Science Education; Gunstone, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogborn, J. Science and Commonsense. In Connecting Research in Physics Education with Teacher Education—Volume 2; Vicentini, M., Sassi, E., Eds.; International Commission of Physics Education: Singapore, 2008; Available online: https://web.phys.ksu.edu/icpe/Publications/teach2/Ogborn.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Niedderer, H. Überblick über Lernstudien in der Physik [Overview of learning studies in physics]. In Lernen in den Naturwissenschaften [Learning in science]; Duit, R., von Rhöneck, C., Eds.; IPN: Kiel, Germany, 1996; pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- National Assessment Governing Board. Science Framework for the 2009 National Assessment of Educational Progress. 2008. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED502955.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Krajik, J.S. The Importance, Cautions and Future of Learning Progression Research. In Learning Progressions in Science. Current Challenges and Future Directions; Alonzo, A.C., Gotwals, A.W., Eds.; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popham, W.J. The lowdown on learning progressions. Educ. Leadersh. 2007, 64, 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, G.W.; Neumann, I.; Liang, L.L.; Neumann, K. Empirical Validation of a Learning Progression for Newton’s Third Law Using Items from the Force Concept Inventory [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching (NARST), Rio Grande, Puerto Rico, 6–9 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, D.C.; Alonzo, A.C.; Schwab, C.; Wilson, M. Diagnostic assessment with ordered multiple-choice items. Educ. Assess. 2006, 11, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadenfeldt, J.C.; Bernholt, S.; Liu, X.; Neumann, K.; Parchmann, I. Using ordered multiple-choice items to assess students’ understanding of the structure and composition of matter. J. Chem. Educ. 2013, 90, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSessa, A.A. Knowledge in Pieces. In Constructivism in the Computer Age; Forman, G., Pufall, P.B., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, D. How consistently do students use their alternative conceptions? Res. Sci. Educ. 1993, 23, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosniadou, S.; Vamvakoussi, X.; Skopeliti, I. The Framework Theory Approach to the Problem of Conceptual Change. In International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change; Vosniadou, S., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2008; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vosniadou, S. Refraiming the Classical Approach to Conceptual Change: Preconceptions, Misconceptions and Synthetic Models. In Second International Handbook of Science Education; Fraser, B., Tobin, K., McRobbie, C.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosniadou, S. Conceptual Change Research: An Introduction. In International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change; Vosniadou, S., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2008; pp. xiii–xxviii. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.; Tolmie, A.; Howe, C.; Mayes, T.; Mackenzie, M. Mental Models of Motion? In Models in the Mind. Theory, Perspective & Application; Rogers, Y., Rutherford, A., Bibby, P.A., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1992; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, L.; Hogg, K.; Zollman, D. Model analysis of fine structures of student models: An example with Newton’s third law. Am. J. Phys. 2002, 70, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, C.; Battaglia, O.R. Conceptual Understanding of Newtonian Mechanics Through Cluster Analysis of FCI Student Answers. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2019, 17, 1497–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; MacIsaac, D. An investigation of factors affecting the degree of naïve impetus theory application. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2005, 14, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D. The effect of the direction of motion on students’ conceptions of forces. Res. Sci. Educ. 1994, 24, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, R.; Heckler, A.F. Systematic study of student understanding of the relationships between the directions of force, velocity, and acceleration in one dimension. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Phys. Educ. Res. 2011, 7, 020112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger, D.; Byard, M.; Driver, R.; Draper, S.; Hartley, R.; Hennessy, S.; Mohamed, R.; O’Malley, C.; O’Shea, T.; Scanlon, E. The conception of force and motion of students aged between 10 and 15 years: An interview study designed to guide instruction. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1994, 16, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, D.; Wells, M.; Swackhamer, G. Force concept inventory. Phys. Teach. 1992, 30, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, A.M.; von Aufschnaiter, C.; Vorholzer, A. Effects of conceptual and contextual task characteristics on students’ activation of mechanics conceptions. Eur. J. Phys. 2021, 42, 025702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Li, M. Validating a partial-credit scoring approach for multiple-choice science items: An application of fundamental ideas in science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2021, 43, 1640–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, R.K.; Sokoloff, D.R. Assessing student learning of Newton’s laws: The force and motion conceptual evaluation and the evaluation of active learning laboratory and lecture curricula. Am. J. Phys. 1998, 66, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, R. Diagnosing Pupils’ Understanding. Forces and Motion 1: Identifying Forces. Evidence-Informed Practice in Science Education (EPSE) Project Diagnostic Question Set; University of York Science Education Group: York, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, R. Diagnosing Pupils’ Understanding. Forces and Motion 2: The Link between Force and Motion. Evidence-Informed Practice in Science Education (EPSE) Project Diagnostic Question Set; University of York Science Education Group: York, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hessisches Kultusministerium 2016 Kerncurriculum Gymnasiale Oberstufe Physik. Available online: https://kultusministerium.hessen.de/sites/default/files/media/kcgo-ph.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Blüggel, L.; Hegemann, A.; Schmidt, M. Impulse Physik (Oberstufe); [Impulse Physics (Senior Level)]; Ernst Klett Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany; Leipzig, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grehn, J.; Krause, J. Metzler Physik [Metzler Physiscs], 4th ed.; Schroedel: Braunschweig, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Demtröder, W. Experimentalphysik 1 (Mechanik und Wärme) [Experimental Physics 1 (Mechanics and Heat)], 8th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giancoli, D.C. Physik (Lehr- und Übungsbuch) [Physics (Text- and Workbook)], 3rd ed.; Pearson Studium: München, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tipler, P.A.; Mosca, G. Physik (Für Wissenschaftler und Ingenieure) [Physics (for Scientists and Engineers)], 6th ed.; Wagner, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haladyna, T.M.; Downing, S.M.; Rodriguez, M.C. A review of multiple-choice item-writing guidelines for classroom assessment. Appl. Meas. Educ. 2002, 15, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, P. Multiple choice items: How to gain the most out of them. Biochem. Educ. 1991, 19, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, I.; Fulmer, G.W.; Liang, L.L. Analyzing the FCI based on a force and motion learning progression. Sci. Educ. Rev. Lett. 2013, 2013, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, A.; Hartig, J.; Rupp, A.A. An NCME instructional module on booklet designs in largescale assessments of student achievement: Theory and practice. Educ. Meas. 2009, 28, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, W.J.; Staver, J.R.; Yale, M.S. Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. A User’s Guide to Winsteps® Ministep Rasch-Model Computer Programs: Program Manual 5.2.3. Available online: https://www.winsteps.com/winman/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Rost, J. Lehrbuch Testtheorie, Testkonstruktion [Textbook Test Theory, Test Construction], 1st ed.; Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, W.J.; Staver, J.R. Advances in Rasch Analyses in the Human Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Robitzsch, A.; Kiefer, T.; Wu, M. Package ‘TAM’. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/TAM/TAM.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Robitzsch, A.; Kiefer, T.; George, A.C.; Uenlue, A. Package CDM. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/CDM/CDM.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 5th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer, D.; Wilhelm, T. Aristoteles siegt immer noch über Newton. Unzulängliches Dynamikverstehen in Klasse 11 [Aristotle still triumphs over Newton. Inadequate understanding of dynamics in grade 11]. Math. und Nat. Unterr. 1997, 50, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J. Mathematische Modellbildung und Videoanalyse zum Lernen der Newtonschen Dynamik im Vergleich; [Comparison of Mathematical Modeling and Video Analysis for Learning Newtonian Dynamics]; Logos Verlag Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Aufschnaiter, C.; Rogge, C. Misconceptions or missing conceptions? Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Tech. Educ. 2010, 6, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redish, E.F. Changing Student Ways of Knowing: What Should our Students Learn in a Physics Class? Invited talk presented at the conference World View on Physics Education 2005: Focusing on Change, Delhi, India, 21–26 August 2005. Available online: http://physics.umd.edu/perg/papers/redish/IndiaPlen.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Berufsverband Deutscher Psychologinnen und Psychologen & Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie. Berufsethische Richtlinien des Berufsverbandes Deutscher Psychologinnen e.V. [Professional Ethical Guidelines of the Professional Association of German Psychologists e.V.]. 2016. Available online: https://uni-giessen.de/fbz/fb06/psychologie/ethikkommission/downloads-intern/ethischerichtlinien (accessed on 14 March 2023).

| Model | Npars | Deviance | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 291 | 16,699.57 | 18,408.36 |

| Model 2a | 293 | 16,475.63 | 18,196.16 |

| Model 2b | 293 | 16,636.45 | 18,356.98 |

| Model 2c | 293 | 16,657.74 | 18,378.27 |

| Model 3 | 296 | 16,462.56 | 18,200.70 |

| Variable | B | 95% CI for B | SE B | β | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Model 1 (F(2, 45) = 24.391, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.520, R2adj = 0.499, ΔR2 = 0.520 *** | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −0.421 | −0.691 | −0.151 | 0.134 | ||

| Control Variables | L4_L3 | 1.003 | 0.506 | 1.500 | 0.247 | 0.427 *** |

| L4_L2 | 2.511 | 1.712 | 3.310 | 0.397 | 0.665 *** | |

| Model 2 (F(4, 43) = 15.744, p < 0.001, R2= 0.594, R2adj = 0.557, ΔR2 = 0.074 *) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −0.182 | −0.580 | 0.216 | 0.197 | ||

| Control Variables | L4_L3 | 0.868 | 0.374 | 1.361 | 0.245 | 0.369 *** |

| L4_L2 | 2.544 | 1.722 | 3.366 | 0.408 | 0.674 *** | |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.552 | −0.988 | −0.116 | 0.216 | −0.256 * |

| mf_fm | 0.280 | −0.171 | 0.732 | 0.224 | 0.134 | |

| Model 3 (F(6, 41) = 11.718; p < 0.001, R2 = 0.632, R2adj = 0.578, ΔR2 = 0.037) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 0.027 | −0.413 | 0.468 | 0.218 | ||

| Control Variables | L4_L3 | 0.852 | 0.363 | 1.340 | 0.242 | 0.363 ** |

| L4_L2 | 2.718 | 1.893 | 3.543 | 0.409 | 0.720 *** | |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.484 | −0.915 | −0.052 | 0.213 | −0.224 * |

| mf_fm | 0.272 | −0.170 | 0.713 | 0.218 | 0.130 | |

| Contextual Task Charac. | h_v | −0.344 | −0.775 | 0.088 | 0.214 | −0.165 |

| o_p | −0.199 | −0.619 | 0.220 | 0.208 | −0.093 | |

| Variable | B | 95% CI for B | SE B | β | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Model 1 (F(1, 30) = 1.358, p = 0.253, R2 = 0.043, R2adj = 0.011, ΔR2 = 0.043) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −2.385 | −2.993 | −1.776 | 0.298 | ||

| Control Variable | L4_L3 | 1.965 | −1.478 | 5.407 | 1.686 | 0.208 |

| Model 2 (F(3, 28) = 8.215; p < 0.001, R2= 0.468, R2adj = 0.411, ΔR2 = 0.425 ***) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −3.005 | −3.868 | −2.143 | 0.421 | ||

| Control Variable | L4_L3 | 0.358 | −2.432 | 3.149 | 1.362 | 0.038 |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.276 | −1.249 | 0.696 | 0.475 | −0.083 |

| mf_fm | 2.227 | 1.237 | 3.217 | 0.483 | 0.656 *** | |

| Model 3 (F(5, 26) = 5.333; p = 0.002, R2 = 0.506, R2adj = 0.411, ΔR2 = 0.038) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −3.156 | −4.182 | −2.130 | 0.499 | ||

| Control Variable | L4_L3 | 0.370 | −2.459 | 3.199 | 1.376 | 0.039 |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.342 | −1.327 | 0.643 | 0.479 | −0.102 |

| mf_fm | 2.366 | 1.348 | 3.384 | 0.495 | 0.697 *** | |

| Contextual Task Charac. | h_v | 0.590 | −0.408 | 1.587 | 0.485 | 0.180 |

| o_p | −0.460 | −1.465 | 0.546 | 0.489 | −0.133 | |

| Variable | B | 95% CI for B | SE B | β | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Model 1 (F(1, 41) = 0.028; p = 0.869, R2 = 0.001, R2adj = -0.024, ΔR2 = 0.001) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −0.649 | −0.960 | −0.338 | 0.154 | ||

| Control Variable | L4_L3 | 0.049 | −0.540 | 0.637 | 0.291 | 0.026 |

| Model 2 (F(3, 39) = 4.339; p = 0.010, R2= 0.250, R2adj = 0.193, ΔR2 = 0.250 **) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −0.502 | −0.936 | −0.069 | 0.214 | ||

| Control Variable | L4_L3 | −0.172 | −0.718 | 0.374 | 0.270 | −0.092 |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.615 | −1.097 | −0.134 | 0.238 | −0.359 * |

| mf_fm | 0.649 | 0.155 | 1.142 | 0.244 | 0.385 * | |

| Model 3 (F(5, 37) = 6.194; p < 0.001, R2 = 0.456, R2adj = 0.382, ΔR2 = 0.205 **) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −0.177 | −0.611 | 0.258 | 0.214 | ||

| Control Variable | L4_L3 | −0.252 | −0.738 | 0.233 | 0.239 | −0.135 |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.523 | −0.948 | −0.097 | 0.210 | −0.305 * |

| mf_fm | 0.642 | 0.209 | 1.074 | 0.214 | 0.381 ** | |

| Contextual Task Charac. | h_v | −0.775 | −1.198 | −0.353 | 0.209 | −0.463 *** |

| o_p | 0.057 | −0.375 | 0.489 | 0.213 | 0.033 | |

| Variable | B | 95% CI for B | SE B | β | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Model 1 (F(2, 45) = 0.129; p = 0.879, R2 = 0.006, R2adj = −0.038, ΔR2 = 0.006) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 1.766 | 1.317 | 2.215 | 0.223 | ||

| Control Variables | L4_L3 | −0.015 | −0.840 | 0.811 | 0.410 | −0.005 |

| L4_L2 | 0.324 | −1.003 | 1.651 | 0.659 | 0.074 | |

| Model 2 (F(4, 43) = 4.509; p = 0.004, R2= 0.296, R2adj = 0.230, ΔR2 = 0.290 ***) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 2.557 | 1.952 | 3.162 | 0.300 | ||

| Control Variables | L4_L3 | 0.381 | −0.369 | 1.132 | 0.372 | 0.141 |

| L4_L2 | 1.368 | 0.118 | 2.618 | 0.620 | 0.314 * | |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.542 | −1.204 | 0.121 | 0.329 | −0.218 |

| mf_fm | −1.293 | −1.979 | −0.607 | 0.340 | −0.537 *** | |

| Model 3 (F(6, 41) = 3.449; p = 0.008, R2 = 0.335, R2adj = 0.238, ΔR2 = 0.040) | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 2.795 | 2.112 | 3.478 | 0.338 | ||

| Control Variables | L4_L3 | 0.388 | −0.369 | 1.145 | 0.375 | 0.143 |

| L4_L2 | 1.543 | 0.264 | 2.822 | 0.633 | 0.354 * | |

| Conceptual Task Charac. | N1_N2 | −0.464 | −1.132 | 0.204 | 0.331 | −0.186 |

| mf_fm | −1.303 | −1.987 | −0.619 | 0.339 | −0.541 *** | |

| Contextual Task Charac. | h_v | −0.306 | −0.975 | 0.363 | 0.331 | −0.127 |

| o_p | −0.351 | −1.001 | 0.299 | 0.322 | −0.143 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Just, A.M.; Vorholzer, A.; von Aufschnaiter, C. Employing a Force and Motion Learning Progression to Investigate the Relationship between Task Characteristics and Students’ Conceptions at Different Levels of Sophistication. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050444

Just AM, Vorholzer A, von Aufschnaiter C. Employing a Force and Motion Learning Progression to Investigate the Relationship between Task Characteristics and Students’ Conceptions at Different Levels of Sophistication. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(5):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050444

Chicago/Turabian StyleJust, Anna Monika, Andreas Vorholzer, and Claudia von Aufschnaiter. 2023. "Employing a Force and Motion Learning Progression to Investigate the Relationship between Task Characteristics and Students’ Conceptions at Different Levels of Sophistication" Education Sciences 13, no. 5: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050444

APA StyleJust, A. M., Vorholzer, A., & von Aufschnaiter, C. (2023). Employing a Force and Motion Learning Progression to Investigate the Relationship between Task Characteristics and Students’ Conceptions at Different Levels of Sophistication. Education Sciences, 13(5), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050444