Abstract

The purpose of this mixed methods study was to identify Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) students with markers of potential challenges on the National Physical Therapy Examination (NPTE) and evaluate their outcomes. The qualitative arm, framed by social cognitive theory, identified strategies students used to achieve first-attempt success. Of the 143 students from one DPT program who had markers of potential NPTE challenges, 79% overcame challenges to achieve success, revealing a weaker association between undergraduate grade point average (GPA) and NPTE performance. Year one program GPA and written exam performance while in the program were stronger predictors of NPTE performance. Qualitative analysis of interviews with 19 graduates revealed three themes: (1) Critical resources build confidence for a unique standardized test; (2) Peers support, teach, and hold each other accountable; and (3) Self-care is vital as emotions run high. Participants described needing to change their approaches to learning between undergraduate and DPT education. Critical resources for achieving first-attempt success included contextualizing knowledge in the clinical setting, NPTE preparatory courses, and frequent self-assessment, which facilitated retrieval practice and revealed knowledge deficits. Little is known about graduates who did not achieve first-attempt success but were ultimately successful, warranting further research.

1. Introduction

To become a licensed Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) and practice in the United States, one must graduate from a program accredited by the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE) and obtain a passing score on the national physical therapy license exam (NPTE), a timed multiple-choice examination. Currently, scores on standardized tests, such as the graduate record examinations (GRE), and undergraduate academic performance are the primary means of predicting first-attempt success on the NPTE [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In one investigation of student and programmatic characteristics associated with first-time and three-year ultimate NPTE pass rates, only one statistically significant variable was identified: students with a mean undergraduate cumulative grade point average (uGPA) >/= 3.52 had a 5.43 greater odds of being in the higher pass rate category than in the lower pass rate category [1]. The purpose of this research study was to identify students in one DPT program with markers of not achieving first-attempt NPTE success (uGPA < 3.52) and evaluate their outcome. We then used qualitative methods to explore the strategies students with academic challenges used to achieve first-attempt NPTE success.

The purpose of the NPTE is to assess basic, entry-level clinician competence. While graduates have a maximum of six attempts to pass the NPTE [7], delayed licensure has significant implications for the individual and the DPT program they graduated from. Graduates who are unsuccessful on their first attempt must wait three months to retake the exam and delay when they can begin to practice as fully licensed clinicians (i.e., not requiring the supervision of a licensed clinician). This limits the graduate’s ability to earn a full salary. Candidates can take the exam up to three times in a 12-month period which requires waiting six months between the third and fourth attempt [8]. There are additional financial burdens imposed on graduates with delayed licensure. First-time test takers’ costs range from $875 to $950. Each subsequent exam attempt costs $585 at a minimum [9,10]. Preparatory courses and texts are also costly. Graduates must begin paying their federal student loans six months after graduation, whether they have secured a license and employment or not [11]. Additionally, candidates who have failed twice or more are unlikely to pass on future attempts [12] and may never practice as DPTs. The stakes are high to achieve first-attempt success on the NPTE.

DPT programs must also meet a benchmark for the ultimate two-year pass rate on the NPTE to maintain accreditation standards [13]. Additionally, first-attempt NPTE success impacts a program’s reputation and qualitative assessment of the national ranking [1]. DPT programs, therefore, seek to admit candidates who can complete a rigorous graduate program and pass the NPTE. This may result in DPT programs relying on standardized test scores to identify candidates who will be successful on the NPTE. However, standardized tests have known gender and racial biases [14,15,16]. Over-reliance on standardized test scores to guide admissions decisions can potentially derail efforts to diversify the racial and ethnic diversity of the physical therapy (PT) profession [17].

These challenges are not unique to the PT profession. Occupational therapy (OT) students must demonstrate professional, academic, and ethical skills and pass the National Board for Certification in Occupational Therapy (NBCOT). Due to accreditation standards, OT programs are also motivated to identify factors that may lead to success on the NBCOT. Kurowski-Burt et al. [18] found that overall college GPA, American College Testing (ACT), or Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores; Occupational Knowledge Exam scores; and performance on clinical education experiences all predicted first-time pass on the NBCOT. Enrolling in an exam review course, reviewing case studies, practicing via simulation, and remediation of coursework such as anatomy and professional foundations were found to assist students with academic challenges in passing the NBCOT on their first attempt.

Similarly, in nursing, through qualitative interviews with graduates of a baccalaureate nursing program, Eddy and Epeneter [19] found that participants who passed the National Council Licensure Examination [for] Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN) on the first attempt accepted responsibility for learning, were proactive in test preparation, took the exam when they felt ready, and used stress management techniques to cope with this challenge. In contrast, unsuccessful participants tended to perceive their lack of success as the responsibility of others, seemed less able to manage stress, and took the exam despite not feeling ready. Such data on DPT graduates who successfully pass the NPTE is not available, warranting further study. This information can inform DPT program faculty and graduates about potential amenable strategies to support first-attempt NPTE success.

Theoretical Framework

While non-cognitive variables such as personality traits and coping skills are not statistically associated with first-attempt success on the NPTE [2,4], self-efficacy may help explain how students with previous academic challenges prepared for and passed the NPTE. Self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in their ability to complete a task successfully [20]. A learner’s belief in their competence can alter their choices and actions as they pursue goals they believe they will accomplish. It also influences how much effort the learner exerts, how much they persevere, and how resilient they are in achieving a goal. Students who believe that they will be successful use more cognitive and metacognitive strategies than those who do not think they will be successful [21]. Self-efficacy is highly context-specific and task-dependent [20,22]. A learner can have high self-efficacy for some tasks (e.g., a practical examination and clinical application of skills) and low self-efficacy for others (e.g., a multiple-choice examination). Self-efficacy is more specific than self-confidence (a general personality trait) and self-esteem [23]. Ultimately, self-efficacy beliefs are strong determinants of accomplishment. However, self-efficacy is not predetermined but can develop over time and is influenced by several antecedents, including self-assessment, coaching, and repeated practice [24]. Self-efficacy has not been examined in NPTE test-takers. Social cognitive theory [25], which highlights individuals’ control over their thoughts and actions, forms the theoretical framework for this research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study leveraged a mixed methods explanatory sequential design [26] with quantitative data collection and analyses informing qualitative data collection and analyses. The qualitative arm of the study was grounded in phenomenology. Phenomenology is a careful examination of human experiences focused on how people make sense of their engagement in the world and life experiences. This qualitative inquiry method also focuses on making meaning of participants’ experiences with a shared phenomenon [27,28], such as preparing for the NPTE.

2.2. Research Questions

RQ1: To what extent does a uGPA predict first-attempt success on the NPTE for graduates of one DPT program?

RQ2: To what extent do admissions and academic factors differ among groups of students with an uGPA of less than 3.52 who are successful vs. unsuccessful at passing the NPTE the first time?

RQ3: What are the resources and learning strategies students with academic challenges use to achieve first-attempt success on the NPTE?

2.3. Participants and Context

One graduate school of health sciences in the northeast region of the United States served as the study context. The school has entry-level and post-professional programs in PT, occupational therapy, physician assistant studies, speech-language pathology, nursing, and genetic counseling. The DPT class includes 70 students supported by 21 faculty members. DPT students complete two years of didactic coursework followed by a year-long clinical internship. Before the internship, students must pass a curricular comprehensive examination that includes both practical and written components. The written portion is a 110-item multiple-choice exam. Students graduate four months into the internship and are eligible to sit for the NPTE. Graduates who pass the licensure exam complete the remaining eight months of the year-long internship as licensed DPTs while continuing to receive mentorship [29].

Since 2021, in addition to the didactic coursework, the program guides students’ NPTE preparation requiring that students complete two versions of the Practice Exam and Assessment Tool (PEAT), a timed, computer-based, multiple-choice practice exam for NPTE candidates developed by The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy [30]. Students take one PEAT five months before the NPTE and a second a month before the NPTE. The PEAT allows students to familiarize themselves with the types of questions on the NPTE. Students receive a detailed performance report by content area (such as body systems and professional work activities) and meet with their academic advisor to share their exam preparation plan. In addition, a student-run club hosts an NPTE preparatory course four months before the NPTE. While attendance is not mandatory, most students choose to attend. Texts purchased for the preparatory courses include multiple, timed practice tests, and students are advised to purchase additional PEAT exams.

The DPT program underwent a curricular revision in 2016, resulting in a substantially different, integrated modular curriculum [31]. During the process of curricular revision, the program also changed its admissions procedure to decrease emphasis on standardized test scores and use a holistic admissions process [32]. Students complete 15 four-week-long intensive courses as well as clinical education experiences over the course of two years. Students participate in three full-time clinical education experiences (CE) during the academic program. Clinical Education Experience 1 and 2 (CE1; CE2) are 10-week full-time experiences and the internship serves as CE3. Physical therapists practice in a variety of healthcare settings post-graduation. Therefore, CE settings vary, including Acute or Post-acute (PAC) and Outpatient settings. Acute or PAC include acute hospital, skilled nursing facility (SNF), inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), or homecare. Outpatient settings include outpatient hospital or private practice settings and school systems.

Each didactic course in the program culminates in a written multiple-choice and practical examination to assess students’ clinical reasoning and psychomotor skills. Each semester in this lock-step program includes either two or three courses. After the first semester, students with a GPA of less than 3.3 are offered supplemental instruction (weekly small group tutoring led by a graduate of the program). Additionally, students are offered a consultation with an Academic Support Counselor and the Office of Justice, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Students must obtain a GPA of 3.0 to graduate.

The quantitative arm of this study included demographic and academic performance data from students who matriculated into the DPT program between 2016 and 2019, completed the redesigned curriculum, graduated, and took the NPTE between 2019 and 2022. The qualitative arm of this study included students who graduated between 2019 and 2022 with a uGPA of less than 3.52 and were successful at passing the NPTE on the first attempt. Participants were excluded from the study if they graduated from the program before 2019, had a uGPA greater than or equal to 3.52, or did not achieve first-attempt success on the NPTE.

2.4. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the MGB Human Research Committee (protocol number 2022P000290). Participants in the qualitative arm of the study reviewed an information sheet and the interview protocol before participating in a virtual interview and received a $100 Amazon gift card for their participation. Participants were informed that researchers would deidentify all study data and report only aggregate data. Participants were asked not to share specifics about NPTE content but to focus on their preparation and feelings before and after the examination. To safeguard participant time, criteria for stopping data collection included monitoring when data saturation had occurred. Data saturation was defined as no new codes or themes emerging during concurrent thematic analysis.

2.5. Instrumentation

An interview protocol was drafted using questions developed by Eddy and Epeneter [19] who interviewed graduates of a baccalaureate nursing program about the NCLEX. The original protocol developed for our study included 13 items. The protocol was reviewed by the four DPT faculty members on the research team for content validity (JB, CS, LP, and KN), and the revised version included 16 items. Thereafter, one of the researchers conducted a cognitive interview with a 2021 graduate of the program who had achieved a first-attempt NPTE pass. Cognitive interviewing offers insights about a respondent’s thought process as they read or hear an item and respond to a question. The purpose of cognitive interviewing and testing is to establish face validity and explore whether participants consistently understand the questions in the way intended by the researchers [33]. The participant’s responses resulted in a modification to four items and the addition of follow-up questions. For example, an original item read, “How were your classroom experiences helpful in preparing for the exam? Not helpful?” The participant felt that the term “classroom experiences” was vague, and this question was reworded to “How was the didactic program helpful in preparing for the exam? Not helpful?” Content validity was supported by revisions by the four faculty members of the research team. The final protocol included 17 items and two demographic questions (see Appendix A).

2.6. Data Collection and Analysis

2.6.1. Phase 1: Quantitative Data Analysis

Graduates with an uGPA of less than 3.52 with admission between 2016 and 2019 and graduation between 2019 and 2022 were included in the study sample. The main outcome measure was the result of students’ first attempt on the NPTE (successful/unsuccessful), and students were categorized into two groups based on this outcome. Students were identified as successful with a score of 600 or greater or unsuccessful with a score of less than 600. Pre-admission factors included: age (years); gender identity (female or male) and race categorized into White and racial/ethnic minority due to the small number of students in each of the minoritized categories. Cumulative undergraduate and total pre-requisite GPA were measured as 0–4; first-generation college student (yes/no); and English as a second language (ESL; yes/no).

Additional potential predictors included the following: GPA at completion of program’s year 1, year 2, and year 3 academic years (0–4.0); performance on curricular comprehensive written examination (0–100); students scoring below a GPA of 3.3/4.0 at the end of any term (yes/no); and students placed on academic probation (yes/no). Academic probation was defined as a cumulative GPA less than 3.0 during any semester(s) of the program, any course failure (below 73%; yes/no); any written exams below 80% (yes/no). We also included data on the proportion of students who took a Leave of Absence (LOA) identified as none, failure, or voluntary (yes/no); students with any professional behavior advisements (yes/no); the number of oral warnings (yes/no); number of written warnings (yes/no); and students with accommodations at any point in the academic program (yes/no).

Student demographic and academic factors were compared using non-parametric t tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. To determine the order of predictive power for the association of demographic and academic factors and NPTE performance researchers used a random forest model [34]. The random forest model approach is based on a decision tree-based algorithm aimed at estimating the importance of relevant predictors. It merges multiple decision trees for a more accurate result and allows for uncovering linear and non-linear signals in the data. One useful output from the random forest model is the ordering of predictors based on how well the predictor explains the variance in the dependent variable. The overall performance of the predictive model can be represented by the generalized R-Square statistic.

2.6.2. Phase 2: Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

Graduates who met the inclusion criteria of uGPA < 3.52 and first attempt pass on the NPTE (N = 113) received a recruitment email to participate in a 1:1 interview. The first twenty respondents were invited to interview. The interview was conducted virtually using Zoom by one of two researchers (KN or LP). Interviews were audio-recorded, and then data were transcribed, deidentified, checked for accuracy, and sent to the participants for member checking.

Researchers used NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2020) and inductive coding to code across the data set, as no pre-existing coding frame existed. Two researchers (KN and LP) then completed the first cycle coding [35]. Each researcher independently coded the same transcript and then met to decide on one set of shared codes. The researchers agreed that the coding process would allow for emergent coding. The researchers then coded four more transcripts independently and agreed on a second set of shared codes. During this second coding meeting, the researchers reviewed the transcripts together and discussed the emergence of new codes, which included codes such as “the impact of the pandemic.” Researchers discussed common codes and emerging themes, added the new codes to the codebook, and coded the remaining transcripts independently before a third coding meeting. At the final coding meeting, researchers identified groups of codes that formed themes. Finally, the researchers re-read the transcripts to check the validity of the draft themes and adjusted the theme statements for accuracy.

Member checking, data triangulation, and researcher triangulation contributed to trustworthiness in the qualitative inquiry [36]. Participants reviewed their transcripts to verify the accuracy with the opportunity to reach out to researchers with additional comments or questions. The researchers also leveraged two forms of triangulation: data triangulation and researcher triangulation. Data triangulation included analyzing interview transcripts and field notes. Researcher triangulation leveraged data analysis performed by two researchers with experience in qualitative research, coding independently, and then meeting to agree on codes.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

The classes of 2019–2022 included 263 graduates who sat for the NPTE in their respective years. Of those students, 143 had a cumulative undergraduate GPA of less than 3.52 out of 4.0 (range 2.08–3.5). Among those students, 113 (79%) were successful (S) on the first attempt of the NPTE and 30 (21%) were unsuccessful (UN). Table 1 compares demographic and admission factors for students who were successful compared to those who were unsuccessful on the first attempt at the NPTE. On average, students with a successful first attempt were younger (S: 24.3 vs. UN: 25.8 years; Cohen’s d = 0.38, small effect size). A greater proportion of students who were not successful on the first attempt were from a racial/ethnic minority group (S: 52, 48.2% vs. UN: 22, 73.3%). All 30 students who were unsuccessful at their first attempt on the NPTE were successful at a subsequent attempt.

Table 1.

Demographic and Academic Performance Factors for Students with an Undergraduate Cumulative GPA < 3.52 and with First Attempt Success on the NPTE compared to Students with an Unsuccessful First Attempt on the NPTE.

Several academic performance factors were statistically significantly different between students who were successful compared to those who were unsuccessful, including first, second, and third-year program GPA, curricular comprehensive written exam performance, any terms with a GPA less than 3.3, any terms on academic probation, any course failures, any course final written exam scores below 80%, leave of absence, and PEAT performance (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Academic Factors for Students with an Undergraduate Cumulative GPA < 3.52 and with First Attempt Success on the NPTE compared to Students with an Unsuccessful First Attempt on the NPTE.

We used the following variables to determine the order of predictive power for demographic and academic factors and the association with NPTE performance: age, gender identity, race category, first-generation college student, ESL, uGPA, pre-requisite GPA, year 1 GPA, curricular comprehensive written exam performance, any terms with a GPA less than 3.3, any terms on academic probation, any course failures, any course final written exam scores below 80%, leave of absence, professional behavior advisement, oral warning, written warning, accommodations, and type of clinical setting of CE1, CE2, and CE3. Performance on the PEAT was excluded from the final analysis based on the number of missing scores. As the PEAT was administered beginning with the graduating class of 2021, there was a non-random expectation of missing data from the classes of 2019 and 2020. Additionally, due to the high correlation between year 1, year 2, and year 3 GPA (0.92, p < 0.001), year 1 was selected as the factor to represent GPA as it serves as an early and amenable risk factor.

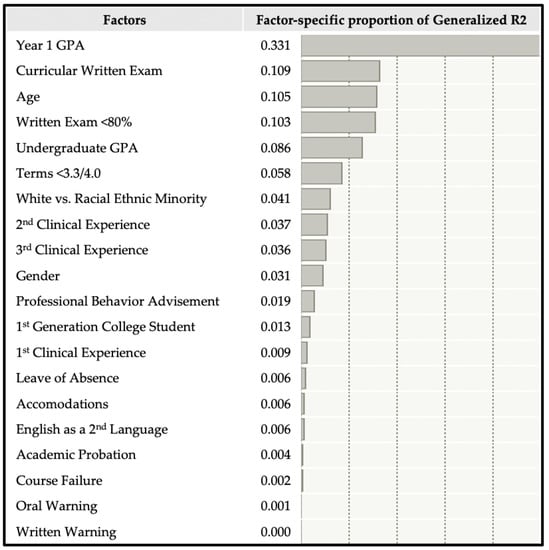

Based on the selected variables, the random forest model resulted in a generalized R-Square of 0.62, indicating that 62% of the variance for the association between the demographic and academic factors and NPTE performance can be explained by the study variables (Figure 1). The demographic and academic factors with the strongest predictive power of NPTE performance were year 1 program GPA (R2 0.62 × Portion 0.33 = 0.205), which has a unique contribution of 20.5% of explained variance, curricular written exam (6.8%), any written exam scores below 80% (6.4%), and undergraduate cumulative GPA (5.3%).

Figure 1.

Predictive power for the association of student demographic and academic factors and NPTE performance. Generalized R-Square = 0.617.

3.2. Qualitative Results

The first 20 participants who responded to the recruitment email were asked to participate in a 1:1 interview with the researchers. One participant did not show up for the scheduled interview. Demographic data on the 19 interview participants are available in Table 3. Thematic analysis resulted in three themes: (1) Critical resources build confidence for a unique standardized test; (2) Peers support, teach, and hold each other accountable; and (3) Self-care is vital as emotions run high. Table 4 includes themes, sample codes, and additional excerpts.

Table 3.

Demographic data of interview participants.

Table 4.

Themes, sample codes, and excerpts.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Critical Resources Build Confidence for a Unique Standardized Test

All participants had taken standardized tests, such as the SAT and GRE, when applying to undergraduate and graduate programs, describing varying test-taking abilities and self-efficacy. They felt that previous standardized tests were less focused on a specific knowledge base and more on the ability to take a test. The NPTE, however, required both a discipline-specific knowledge base and advanced test-taking skills. With previous standardized tests, many participants described that repeated testing was beneficial to build test-taking skills; however, success on the NPTE required frequent practice testing to reveal gaps in knowledge and then focused study between practice exams:

I would take a practice GRE, see my score, and then just go through the refining process. And through that you see your score going up and up. I find that standardized testing for me was just building that knack for those strategies(Participant 6)

Most participants took at least one NPTE preparatory course and felt one of the most helpful aspects of the preparatory course was the guidance for mapping a study schedule. The timing of the preparatory course also served as a “kick-off” to examination preparation. All participants discussed the importance of time management and having a consistent schedule dedicated to studying to stay on track. Most participants started studying at least three months before the exam. “A lot of it was just schedule, having the time set aside to study specifically for it” (Participant 2). Having sufficient time to dedicate to studying and a detailed schedule helped to contribute to strong mental health during this stressful period.

An important aspect of preparation for the NPTE included participants’ CEs. Students described that during CE, when they were involved in direct patient care, they were often exposed to content areas that they may not have covered during the didactic aspect of the program or were exposed to in greater depth while caring for patients. Additionally, patient care allowed the participants to contextualize their knowledge. Abstract knowledge was now attached to a specific person, which helped them to remember content. However, there were still times when there was a disconnect between studying for the NPTE and the knowledge participants felt that they needed for clinical practice:

The breadth of knowledge that I needed to know [for the exam] was the most difficult—more than we even talked about it. Obviously, we can’t get through everything that’s on the NPTE at school. At school, we’re more focused on actually becoming good clinicians. So, it’s not like focusing on the NPTE. But there are things that I just literally have never heard of that I’m trying to study up on(Participant 15)

To be able to store this vast amount of knowledge, retrieval practice through practice questions was described as the most effective study strategy used by participants. Even when studying in groups with peers, the focus was on developing and reviewing practice questions. Most participants described taking several practice tests (between 5–7) spending much of their time reviewing the tests to identify knowledge deficits.

I would take a practice exam. The next day, I would go over it, and then go over the questions that I missed. And either questions I missed or concepts that I guessed, and I could see myself missing out on the actual exam. I’d write it down. The next day, I’d make study guides based on concepts I need to go over(Participant 10)

Preparatory courses and practice tests provided participants with an appropriate expectation of the NPTE. Participants would initially take practice tests at home, with distractions, and multiple breaks, getting up and acting out scenarios (such as questions about gait and body mechanics). However, as the time to the NPTE grew closer, participants attempted to replicate the testing environment which would involve remaining seated for many hours. Participants would not be able to rely on their psychomotor skills, which are heavily emphasized in DPT programs. During practice and in the actual examination, participants flagged questions that were challenging, and reviewed those at the end of each exam section. Most participants learned not to change answers and trust their initial instincts unless they had a strong rationale.

I’m not a fan of changing my answers because I always feel like there’s a reason I chose the first one. And usually, that reason is correct. The ones that I struggled with a lot, I didn’t answer, I just tagged them and then went to the next one…it’s about 5 to 10% of the time that I would have actually changed my answer(Participant 16)

Most participants were also preparing for the examination during the pandemic. Social distancing measures were a perceived benefit to some participants as there were fewer distractions. Many were willing to sacrifice during this time to ultimately achieve their goal of becoming DPTs. Preparing for the NPTE was seen as the final hurdle: “Just from talking to my classmates, I think the people who sacrificed a little bit to study were the people who are more successful”(Participant 3).

A dedicated study schedule and taking practice examinations helped to build confidence. Although performance on sections of the practice examinations improved, which helped to confirm that the study strategies were effective, many participants did not achieve a passing score on the practice tests until just prior to the NPTE. This led to increased self-efficacy going into the examination; however, most participants described leaving the examination feeling as if they were unsuccessful. Upon reflection, they acknowledged that they had worked hard and should have trusted in the process.

3.2.2. Theme 2: Peers Support, Teach, and Hold Each Other Accountable

Most participants had changed their approach to studying between undergraduate and post-graduate programs. They described relying on a passive approach to learning and using rote memorization to succeed in written examinations in undergraduate programs. However, in the DPT program, they focused on gaining an understanding of key concepts and applying foundational knowledge. They relied on collaborative learning and group study to be successful. Most participants continued to study in groups (at least some of the time) to prepare for the NPTE.

In undergrad, it was more about just getting answers, memorizing a quick answer … but in PT school, knowing that these are concepts I’m going to be applying for life, I really had to delve in deep and understand, why was I doing this? Why are these concepts important? Learning how to make it stick in my brain was actually me lecturing and teaching these concepts. Either teaching myself or just teaching my classmates when we have review sessions. That exposed a lot of what I do know, and what I don’t know(Participant 6)

There were numerous benefits to group discourse, but many participants remarked that group study helped hold them accountable to others. Preparing for the exam took, on average, at least three months of intense preparation. Regular touchpoints with their peers helped to sustain momentum. While preparing for the NPTE, participants were either in year-long clinical internships or working full-time. Participants needed to be prepared for the group study session, so that meant independent preparation and then being ready to discuss concepts in the group and teach content to each other.

If you can explain something in detail then you know the content, right? I think that was a productive way to study with other people or groups … question each other and ask someone to explain something to you(Participant 14)

Peer teaching helped participants gain a deeper understanding of a topic, “What you read in a textbook, it’s hard for me to understand it. But when I hear someone else say it in layperson’s terms, or apply it in a different way, it just made sense to me” (Participant 7). Group study also served as a form of self-assessment that helped to reveal gaps in knowledge. This cycle of independent study and then checking in with peers helped to build participant self-confidence. Studying with peers was also a form of self-care as they supported each other during a particularly challenging period. Few outside of their peer group understood what they were experiencing, the pressure of studying for an exam that would allow them to practice in their chosen field.

There are times when I got in my own head. And we would all do the same. We’d all get frustrated, and we would all just pull each other out and remind each other, let’s not have tunnel vision here and see the big picture while improving. We’re almost there! We just kept encouraging each other. We took care of each other in that way … whether it’s just cleaning your house, or even just making a meal for all of us during that time, I think that’s been really helpful to just keep our mind sane, supporting each other(Participant 6)

Most participants relied on groups that included 2–4 classmates who were often in different clinical settings, which brought diverse experiences to the group. When asked about additional resources the program could have provided, participants expressed that it would have been helpful to hear from peers in graduating classes how they had approached study preparation. While all participants had relied on group study to succeed in the program, some were not able to leverage groups for NPTE preparation due to the pandemic and social distancing measures or physical distance as classmates traveled back home and out of state.

3.2.3. Theme 3: Self-Care Is Vital as Emotions Run High

Many participants described a host of emotions in the months leading up to the examination. There was fear of not passing the exam and the potential shame of seeing their faculty at conferences and having to share news of their failure. Some participants were in yearlong internships and required licensure to transition out of the student phase of internship to practicing as a licensed clinician. An unsuccessful attempt would mean remaining as a student intern until they could reapply to take the NPTE. Participants envisioned the embarrassment of having to return to the clinical environment and share with patients and staff that they had not passed:

I was so worried that I wasn’t going to pass because I was in a year-long [internship]. And, everyone’s going to know. What do I do if I don’t pass because I’m supposed to be working? I remember I was more nervous about not being able to work for them than I was actually passing(Participant 3)

These were not results that participants would be able to keep private. Participants felt fear and doubt after completing the examination, and surprise and relief upon learning they had passed. One participant described “I cried. I don’t think I’ve ever felt relief like that in my entire life” (Participant 15). Many did not realize the pressure they had been under until it was over. Participants acknowledged the importance of self-care to successful preparation. Almost every participant described some form of movement as a self-care strategy. Participants relied on exercise while they were students in order to succeed in their rigorous program and continued to prioritize exercise while preparing for the exam. Many had been high school and college athletes. Time for exercise was built into their study schedule.

Participants used their knowledge of teaching and learning theory to dedicate focused time to study and then take a scheduled break. Getting enough sleep, spending time with friends and family, and being conscious of nutrition were all priorities. Participants were also conscious of where they were studying. One participant described moving back to school to surround themselves with “like-minded people who were only focusing on studying” (Participant 6). Prioritizing mental health was at the forefront of many participants’ minds. Being fully immersed in study preparation was also described as a form of self-care:

I feel like dedicating time to myself was actually more helpful for me than anything else. In terms of food or mental health, meditation, that type of stuff. I didn’t do any of that. I just felt like, in general, I had less on my plate by just dedicating time to study. And that was enough for me to feel better(Participant 7)

4. Discussion

The NPTE is a high-stakes examination and graduates of DPT programs face immense pressure (both financial and psychological) to achieve first-attempt success. While there are known student and programmatic factors that contribute to NPTE success [1,2,3,4,5,6], there are no studies to date that highlight how DPT students overcome academic challenges to achieve first-attempt success. We identified 143 students from one DPT program who had markers of potential challenges on the NPTE (uGPA of less than 3.52 [1]), a majority of whom (79%) overcame challenges to achieve success.

Social cognitive theory [25] which frames this research, highlights that learners’ thoughts mediate their knowledge and action, and belief about abilities strongly influences learners’ behavior. We framed this research around learner self-efficacy which influences learners’ effort and resilience and develops over time. Self-efficacy development is influenced by mastery experiences, vicarious learning, social persuasion as well as the reduction in stress and negative emotions [20]. We noted these antecedents of self-efficacy in our participants’ responses.

Critical resources included contextualizing knowledge in the clinical setting, engagement in preparatory courses, strategies for retrieval of information, and frequent self-assessment, which revealed knowledge deficits. Brown et al. [37] highlight that to learn, we must retrieve. Testing (or the act of memory retrieval) strengthens the neural routes and solidifies the memory. In this way, frequent testing can result in long-term retention [37]. Participants completed on average five timed practice tests as a means of effortful retrieval to solidify learning and memory. With effective study strategies, participants had multiple opportunities for mastery (a known antecedent of self-efficacy) [22]. As participants saw their scores on practice tests increase, self-efficacy peaked just before the exam.

Participants were recruited based on a low undergraduate GPA ranging from 2.22 to 3.5/4.0. Our study identified a weaker association between uGPA and NPTE performance compared to other academic factors such as year 1 GPA and written exam performance. One explanation for this result is that the participants may have refined their study strategies during graduate school. We gained insight into how participants changed their study approach between undergraduate and graduate studies, particularly around collaborative learning. Interestingly, this contrasts with a study of undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in health sciences courses in one university, where Peixoto et al. [38] found few differences between how undergraduate and graduate students approached learning.

Marton and Saljo [39] highlight two approaches to learning. The surface approach involves memorization and rote learning to passively acquire information presented, and a deep approach involves actively engaging with the material and internalizing the fundamental meaning of the information presented. Participants in our study described relying on rote memorization and short-term memory strategies during undergraduate studies but switching to deeper learning strategies in graduate school. Participants prioritized deeper learning strategies being cognizant of needing to understand and remember concepts they would use throughout their careers as PTs. Our findings contrast Dalomba et al. [40] who found that DPT students demonstrated a higher surface approach to learning compared with OT students in one California school. This incongruence is possibly due to the difference in the study populations that includes DPT graduates in our study, who were preparing for licensure and entry into practice. DPT students may use familiar surface learning approaches as they transition from undergraduate programs but may soon realize the need for long-term retention and adopt deeper learning approaches as evidenced in this study. Not surprisingly, the transition from undergraduate to graduate programs is identified as one of the academic challenges faced by DPT students [41]. Students enrolled in an academically rigorous DPT program must not only acculturate into a new profession but also dramatically change their learning strategies which had worked for them previously. DPT students may benefit from an introduction to the science of learning early in their curricula.

Sources of vicarious learning and social persuasion in this study included peers and academic advisors. Every participant in this study relied on collaborative group work to be successful in their DPT program, and most continued to rely on study groups while preparing for the NPTE. Group work is emphasized in DPT education as reciprocal peer tutoring increases confidence in communication and teamwork [42] and because graduates will form part of an interprofessional collaborative team during professional practice [43]. NPTE study groups offered continued opportunities for mastery and vicarious learning. Studying in groups helped to increase accountability and served as a motivator to sustain effort over the typically three-month-long study period. Few participants talked about the opportunities to learn from role models other than the advice provided by faculty. Some participants offered this as a recommendation for the academic program, to provide panel discussions with graduates who had successfully passed the examination. In this way, vicarious learning could contribute to enhanced self-efficacy for future test takers.

Study groups also offered opportunities for positive talk and ongoing motivation. Effective management of stress and negative emotions is a powerful antecedent to self-efficacy as participants must continue to believe that they will be successful. Low self-efficacy is frequently related to burnout as well as feelings of helplessness or hopelessness [44]. Participants managed stress through physical activity, time with family and friends, getting enough sleep, and proper nutrition. Not surprisingly, given the study population of physical therapists who are movement specialists, almost every participant described some form of movement as self-care.

Quantitative statistical analysis revealed factors associated with not achieving a first-attempt success on the NPTE including a first-year program GPA of less than 3.3. Interestingly, the program had already put strategies in place to support students whose GPA fell below 3.3. While these strategies, including supplemental instruction, were successful in helping students graduate, additional interventions are needed to support NPTE success. While ESL was not one of the leading factors associated with first-time failure on the NPTE in our program, other authors have identified ESL as significantly associated with needing more than one attempt to pass the NPTE [5]. Michaels et al. [45] highlight that learners may be confident in a discipline-specific knowledge base but have difficulty understanding test questions, particularly verbose questions. The use of a tool such as the Language Variation Tool [45] may help to identify learners who misunderstand the meaning of test questions and allow programs to provide targeted intervention on test-taking strategies.

Limitations

This study focused on four cohorts of graduates from one academic institution, one of only three programs in the United States that leverages a modular curriculum, limiting the generalizability of findings. We recruited participants from four cohorts who took the license examination between 2019 and2022 and retrospectively explored their study strategies and self-efficacy surrounding the exam. While most participants who participated in the qualitative aspect of the study took the NPTE between 2021 and 2022 (n = 14), it is possible that the participants who studied for and took the exam before 2021 (n = 5) would have been challenged to recall their specific study strategy and mindset. Future research may benefit from the use of quantitative measures of self-efficacy that could be used to determine whether high levels of self-efficacy before the NPTE can predict first-attempt success. Little is known about students who were unsuccessful the first time they took the NPTE. We do not know how their strategies differed from the students who were successful. Future research should focus on these learners and their persistence, sustaining effort to ultimately achieve mastery.

5. Conclusions

The stakes are high for DPT graduates to achieve first-attempt success on the NPTE. Our study highlights that students with known admissions predictors of challenges on the NPTE (uGPA < 3.52) can achieve first-attempt success by leveraging preparatory courses, group study, and frequent self-assessment to reveal knowledge deficits and facilitate retrieval practice. Analysis of admissions and academic performance data revealed that first-year program written exam performance was more predictive of first-attempt NPTE success or failure than admissions factors. By analyzing program level data, DPT faculty can identify students at risk after the first year in the program and develop interventions to support first-attempt success.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N., J.B., L.P. and C.S.; methodology, K.N., J.B., L.P., C.S. and P.G.; formal analysis, K.N., L.P., C.S. and P.G.; investigation, K.N., J.B., L.P., C.S. and P.G.; resources, K.N. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.N., J.B., L.P., C.S., P.G., J.E.B. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, K.N., J.B., L.P., C.S., P.G., J.E.B. and S.K.; visualization, K.N., J.B., L.P., C.S., P.G., J.E.B. and S.K.; project administration, K.N.; funding acquisition, K.N. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Intramural grant awarded by the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, MGH Institute of Health Professions (HP9340).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the MGB Human Research Committee Intuitional Review Board (protocol code 2022P000290, approved 24 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Protocol

- When did you take the NPTE (January or April)?

- What circumstances led you to take the exam in April?

- How did you feel when you learned that you had passed the NPTE? Were you surprised? Why or why not?

- How did you feel about your score on the exam? Is that what you anticipated? Why or why not?

- Why do you think you passed the NPTE on the first try?

- How did you prepare for the NPTE?

- Did you take a prep course?

- What was the most helpful thing you learned from taking the prep course?

- Did you find the PEAT helpful in preparing for the exam? If so, how? If not, why not?

- How many practice exams did you take in preparation for the exam?

- Did you have a specific strategy of when and how you used the practice exams?

- Did you review the answers of the practice tests?

- Did you replicate the testing situation when you took the practice exams (e.g., following the time limit, limited breaks, wearing a mask etc.)?

- If you replicated the testing situation, did you find it helpful?

- How did your performance on the practice tests inform your exam preparation?

- When did you start preparing for the NPTE?

- Can you estimate how many hours per week you devoted to studying for the NPTE?

- Did you plan out a monthly schedule? Week-to-week?

- Did you work individually or with a group while preparing for the NPTE?

- What was the most effective study strategy that you used?

- What strategies did you use to take care of/prioritize your health and well-being while preparing for the exam?

- What were your feelings during the examination?

- Without sharing content-specific information, was there anything that surprised you about the examination?

- Did anything happen during the exam that affected your performance?

- Without sharing content-specific information, what aspect of the NPTE did you find the most difficult? Why?

- What aspect of the NPTE did you find the least challenging?

- How long did you spend taking the exam?

- Did you review your answers? If you reviewed your answers, how often did you make changes?

- Were there any particular strategies you used while taking the exam that you found to be most effective?

- How would you describe your standardized test-taking abilities prior to entering PT school (e.g., on the GRE or SAT)?

- How would you describe your ability to succeed on written exams during the PT program?

- Did you make any changes to your study strategies between undergrad and PT school?

- How was the DPT curriculum helpful in preparing for the exam? Not helpful?

- How were your clinical experiences helpful in taking the NPTE? Not helpful?

- Can you identify any strategies the PT program could put in place to help students be successful with the NPTE?

- What advice would you give to DPT students preparing to the take NPTE?

References

- Cook, C.; Engelhard, C.; Landry, M.; McCallum, C. Modifiable variables in physical therapy education programs associated with first-time and three-year National Physical Therapy Examination pass rates in the United States. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2015, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolden, M.; Hill, B.; Voorhees, S. Predicting success for student physical therapists on the national physical therapy examination. Phys. Ther. 2020, 100, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddle, D.; Utzman, R.; Jewell, D.; Pearson, S.; Kong, X. Academic difficulties and program-level variables predict performance on the National Physical Therapy Examination for Licensure. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galleher, C.; Rundquist, P.; Barker, D.; Chang, W.-P. Determining cognitive and non-cognitive predictors of success on the national physical therapy examination. IJAHSP 2012, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Salgado, B.; Barakatt, E. Identifying demographic and preadmission factors predictive of success on the national physical therapy licensure examination for graduates of a public physical therapist education program. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2018, 32, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, J.; Thomas, R.M.; Eifert-Mangine, M. Pilot study: What measures predict first time pass Rate on the National Physical Therapy Examination? Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2017, 15, 51960842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSBPT. National Exam (NPTE). Available online: https://www.fsbpt.org/Secondary-Pages/Exam-Candidates/National-Exam-NPTE/Eligibility-%20Requirements (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- FSBPT. Retake Exam. Available online: https://www.fsbpt.org/Secondary-Pages/Exam-Candidates/National-Exam-NPTE/Retake-Exam (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- FSBPT. Exam Registration and Payment. Available online: https://www.fsbpt.org/Our-Services/Candidate-Services/Exam-Registration-Payment (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- FSBPT Schedule Your NPTE Appointment. Available online: https://www.fsbpt.org/Secondary-Pages/Exam-Candidates/National-Exam-NPTE/Schedule-Exam (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Available online: https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/when-do-i-need-to-start-paying-my-federal-student-loans-en-585/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- FSBPT. Important Retake Information for the NPTE. Available online: https://www.fsbpt.org/Secondary-Pages/Exam-Candidates/National-Exam-NPTE/Retake-Exam/Important-Retake-Information (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Standards and Required Elements for Accreditation of Physical Therapist Education Programs. Available online: https://www.capteonline.org/globalassets/capte-docs/capte-pt-standards-required-elements.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Hoffman, J.L.; Lowitzki, K.E. Predicting college success with high school grades and test scores: Limitations for minority students. Rev. High. Educ. J. Assoc. Study High. Educ. 2005, 28, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clawson, T.W. Test anxiety: Another origin for racial bias in standardized testing. Meas. Eval. Guid. 1981, 13, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warne, R.T.; Yoon, M.; Price, C.J. Exploring the various interpretations of “test bias”. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2014, 20, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.; Zafereo, J. Faculty and programmatic influence on the percentage of graduates of color from professional physical therapy programs in the United States. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2021, 26, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowski-Burt, A.L.; Woods, S.; Daily, S.M.; Lilly, C.L.; Scaife, B.; Davis, D. Predicting student success on the National Board for Certification in Occupational Therapy examination. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, L.L.; Epeneter, B.J. The NCLEX-RN Experience: Qualitative interviews with graduates of a baccalaureate nursing program. J. Nurs. Educ. 2002, 44, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv. Behav. Res. Therapy. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 1, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, T.; Pintrich, P.R. Student Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning: A LISREL Model; Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED): Washington, DC, USA, 1991; pp. 127–153.

- Pajares, F. Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Rev. Educ. Res. 1996, 66, 543–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, P.A.; Klehe, U.C. Self Efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Industrial/Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed.; S.G. Rogelberg: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K.M.; Alexander, J.E. The empirical development of an instrument to measure writerly self-efficacy in writing centers. J. Writ. Assess. 2012, 5. Available online: https://escholarship.org/content/qt5dp4m86t/qt5dp4m86t.pdf?t=r071jg (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Bandura, A. National Inst of Mental Health. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA; National Inst of Mental Health: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, A.C.; Creswell, J.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Clegg Smith, K.; Meissner, H.I. Best practices for mixed methods for quality of life research. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochmiller, C.R.; Lester, J.N. An Introduction to Educational Research: Connecting Methods to Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method, Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Portney, L.G.; Knab, M.S. Implementation of a 1-year paid clinical internship in physical therapy. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2011, 15, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSBPT. Practice Exam & Assessment Tool (PEAT). Available online: https://www.fsbpt.org/Our-Services/Candidate-Services/Practice-Exam-Assessment-Tool-PEAT (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Jette, D.; Macauley, K.; Levangie, P. A theoretical framework and process for implementing a spiral integrated curriculum in a physical therapist education program. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2020, 34, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerchen, V.P.; Williams-York, B.P.; Ross, L.J.M.; Wise, D.P.; Dominguez, J.P.; Kapasi, Z.P.; Brooks, S.P. Purposeful recruitment strategies to increase diversity in physical therapist education. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2018, 32, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D. Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Chapter 12: Writing about qualitative research. In Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.C.; Roediger, H.L., III; McDaniel, M.A. Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, H.M.; Peixoto, M.M.; Alves, E.D. Learning strategies used by undergraduate and postgraduate students in hybrid courses in the area of health. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2012, 20, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marton, F.; Saljo, R. On qualitative difference in learning: I—outcome and process. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1976, 46, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaLomba, E.; Mansur, S.; Bonsaksen, T.; Jan Greer, M. Exploring graduate occupational and physical therapy students’ approaches to studying, self-efficacy, and positive mental health. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plack, M.M.; Healey, W.E.; Huhn, K.; Costello, E.; Maring, J.; Hilliard, M.J. Navigating student challenges: From the lens of first-year doctor of physical therapy students. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2022, 36, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seenan, C.; Shanmugam, S.; Stewart, J. Group peer teaching: A strategy for building confidence in communication and teamwork skills in physical therapy students. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2016, 30, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update. Available online: https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2016-Update.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Rahmati, Z. The study of academic burnout in students with high and low levels of self-efficacy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 171, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, N.N.; Stewart, T.; Barredo, R.; Raynes, E.; Edmundson, D.; Kunnu, E. Use of a diagnostic tool to predict performance on high-stakes multiple choice tests: A case study. In Forum on Public Policy Online; Oxford Round Table: Urbana, IL, USA, 2019. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1245878.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).