Abstract

This study explores the motivation of international students who simultaneously studied L2 English and L3 Japanese while learning in an English-taught program specializing in policy studies at a Japanese university. Data were collected from five participants using semi-structured interviews, motivation graphs, a biographical questionnaire, and the program’s application form to examine how international students chose the program and the trajectories of their motivations to learn English, Japanese, and policy studies. The results show that all participants had rich experience in learning English and/or intercultural contacts before coming to Japan. Although two participants wanted to live in Japan to learn the language, three had no specific aim of studying abroad. The students’ motivation to learn English was enhanced when their study became more advanced, but their motivation to learn Japanese was more varied and complex. Although sustaining the motivation to learn Japanese over time seemed demanding, one of the participants invested more time in learning Japanese than English. This study highlights that exploring students’ disposition of motivation and international orientation can be beneficial, especially in uncovering why and how students can sustain their motivation to learn Japanese for academic purposes. Furthermore, it could indicate future directions for such programs.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the number of studies on L3 and languages other than English (LOTE) motivation has increased. Early work on this topic, including Csizér and Dörnyei [1,2,3], was mainly conducted in European contexts and reported that learning L2 and L3 simultaneously is demanding. These studies also indicate that the dominant lingua franca-use of English worldwide negatively affects motivation to learn L3 and LOTEs [4]. Consequently, L3 and LOTE learning “typically takes place in the shadow of Global English” [5] (p. 457). In contrast, recent studies in Asian contexts suggest that the relationship between motivation for learning L2 and LOTEs is more nuanced and dynamic [6].

1.1. Studies on L2 and L3 Motivation in an Asian Context

Like studies conducted in European contexts, motivation research focuses on L2’s relationship with L3 and LOTEs. Studies reported the competitive nature of the relationship, which aligns with previous studies. Some research has also demonstrated an adverse impact of L2 motivation on L3. For example, Simic et al. [7,8] explored international graduate students’ L2 (English) and L3 (Japanese) Willingness to Communicate (WTC) [9] in an English-taught program (ETP) at a Japanese university. Qualitative research uncovered [7] that students perceived Japanese as crucial for maintaining harmony with society but not for their academic studies. The following quantitative research [8] reported that higher English WTC was associated with lower Japanese WTC. In other words, L2 and L3 WTC have a seesaw-like relationship. They concluded that in a current graduate ETP, students came to Japan to pursue a degree. Thus, their L3 motivation decreased as their studies progressed.

In contrast, some other studies reported that the relationship is more dynamic and nuanced [6]. For example, they conducted an interview study in a Thai university using Dörnyei’s L2 motivational self system (L2MSS) as the theoretical framework [10,11]. Some participants were L3 majors while others studied business or management in English-medium instruction (EMI). The results showed that students learning in EMI had more vivid L2 ideal selves than students in L3 majors. Regarding ought-to self, students studying in EMI are strongly concerned about their English proficiency in relation to career opportunities. In contrast, they did not report concern regarding L3 ought-to self. They did not feel obligated to meet anyone’s expectations. Moreover, classes to learn L3 for EMI students were simple enough for them not to feel pressured to pass exams.

Fukui and Yashima [12] conducted a longitudinal qualitative study of Japanese university students studying abroad in Taiwan to learn L2 (English) and L3 (Chinese) using L2MSS as the framework. They reported their motivation to interact with each other in L2 and L3, and sometimes motivation to learn L3 was higher than L2. The study highlighted the struggles of learning L2 and L3 simultaneously and expressed that it was physically and psychologically demanding, especially in study abroad (SA) contexts. They concluded that it is essential for learners to have a community in practicing L3 to sustain and enhance L3 motivation.

Bui and Teng [13] conducted interviews with university students in Hong Kong using dynamic system theory (DST) [14]. They included the impact of L1 (Cantonese) on learning L3 (Japanese) in addition to the influence of L2 (English). The results indicated that some students spent less time learning English after they began to learn L3 due to several reasons. First, students felt a sense of progress when learning L3 more than L2 and similarities between L1 and L3 contributed to learners’ positive L3 learning experiences. They suggested that the shorter language distance (e.g., Chinese speakers learning Japanese as L3) could help sustain motivation to learn L3. Finally, they expressed the complex nature of L2 and L3 learning motivation and the significance of investigating L1 to explore L2 and L3 motivation further.

The research in this section suggested that L3 learning motivation is dynamic and affected by various factors (e.g., local vs. foreign languages, distance between L1, L2, and L3, and having a community to practice outside of the class). Still, compared to the vast amount of research focused on motivation to learn English, L3 studies are scarce. In fact, according to Boo et al. [15], over 70 percent of the research conducted in second language acquisition (SLA) between 2005 and 2014 focused on learning English. On the other hand, currently, people have contact with more than one additional language at some level. The awareness of the phenomenon in society is called the “multilingual turn” [16,17]. It also represents a critical attitude toward the current monolingual bias, in which English receives excess attention [18,19]. In response to this idea, this current research was conducted to contribute to investigating LOTEs further.

1.2. EMI’s Rapid Expansion and Related Motivation Studies

EMI is the use of the English language to teach academic subjects in countries or jurisdictions where the first language (L1) of the majority of the population is not English [20]. As English has become the de facto global language [21], EMI has become the new norm in tertiary education [22], including Japanese universities. Among varieties of EMI, English degree programs (English-taught programs, ETPs) have been used in an effort to attract international students by removing the language barrier to studying in Japan. ETPs were expected to accelerate internationalization on campus. However, the systematic review of EMI in higher education conducted by Macaro et al. [23] indicated that relevant research is limited by rapidly-expanding EMI. They also revealed that Japan is falling behind in research and pedagogical application even among Asian countries [23]. Regarding motivation, Lasagabaster [24] claimed that in the context of EMI, research on motivation has rarely been examined and therefore conducted a quantitative study at a university in the Basque region. He applied L2MSS as the theoretical framework and reported that ideal L2 self, family influence, and attitude toward EMI were beneficial in predicting participants’ intended effort in EMI. He expressed the necessity of further investigation of motivation in EMI, especially using qualitative methods. Finally, despite the growing number of international students in Japanese universities [25], very little research has focused on international students [26]. Galloway and Curle [26] explored international students’ reasons for choosing Japan as their SA destination. They reported learning Japanese and living in Japan to be their primary purposes. They also expressed that further research on international students in ETPs is critical to enhance institutions’ global competitiveness. In spite of being at a preliminary stage, this study is trying to fill the following research gaps: (1) monolingual bias in research on L2 motivation, by focusing on motivation to learn L3/LOTE, (2) motivation in the context of EMI, and (3) in particular, international students’ motivation in an ETP. Specifically, the study considers the following research questions:

- RQ1. Why do international students choose an ETP in Japan?

- RQ2. From individual perspectives, are the motivations to learn English, Japanese, and policy studies related? If so, how?

2. Method

2.1. Research Site, Participants

In this study, data were collected in an ETP (hereafter, Program A) in western Japan. Program A is in the College of Policy Studies, which enrolls approximately 20 students each year from all over the world, including China, India, and England. Program A is aimed at students who are interested in policy studies, especially from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), to recruit possible future leaders. Students are required to have sufficient proficiency in academic English to take EMI; they must have attained TOEFL iBT 71, Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) upper B1, or equivalent when applying. Students must earn 124 credits to graduate from the program, including courses on ecology, economics, and language. Of these, 12 credits must be from English for academic purposes (EAP) courses, regardless of their L1.

Regarding the Japanese language, no proficiency is required to apply to Program A. However, students are encouraged to achieve an intermediate level by graduation. There are six Japanese levels (i.e., Elementary 1, 2, Intermediate 1, 2, Advanced, and Proficient). Students take a placement test and take courses according to the test results. Students must earn another 12 credits from those Japanese language courses if their L1 is not Japanese. These language courses are to be taken alongside their EMI courses.

Participation in this study was voluntary. Maximum variation sampling was applied [27] among the students who were willing to be interviewed. The author chose students from different countries and with different strengths in their L2 based on her teaching experience. Thus, Gabi, Heidi, Pia, Silvia, and Iori (all pseudonyms) have various backgrounds; their profiles are listed in Table 1. The main participants in this study are Gabi, Heidi, and Pia (i.e., Iori and Silvia were excluded for the second round of the interview. Iori had health issues in the previous year and Silvia perceived her L1 as English). Although this study has a small number of participants, Barkhuizen [28] argued that various factors should be considered when deciding the number of participants. Some factors are under the control of the researchers (e.g., research purposes, the scale of the project) and some of these are outside of their control (e.g., participants’ availability, time constraints, and individual resources). Therefore, an appropriate number of participants depends on the study. Sometimes having one participant is enough. The author decided to focus on Gabi, Heidi, and Iori since the purpose of this study is not to try to reach the generalization of L2 and L3 learning experiences in ETPs but instead to explore learning experiences and motivational trajectories from individual perspectives.

Table 1.

Participants’ profiles.

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

To answer the research questions (i.e., why do international students choose an ETP in Japan? From an individual perspective, are the motivations to learn English, Japanese, and policy studies related? If so, how?), qualitative data were collected because it is beneficial to explore new, uncharted areas [27]. In addition, qualitative approaches are valuable when examining reality from an individual perspective and understanding complex phenomena in depth [29,30,31]. Regarding the context of L3 learning, it is much more complicated than L2 learning and therefore research on L3 needs to consider a wide range of factors [19]. For example, the reasons for learning L3 are diverse and complex and the target level learners would like to achieve. Moreover, the value of multilingualism in the societal and educational environments students are in is different. Thus, qualitative approaches are applied in this study.

The data were collected from a biographical questionnaire, interviews, and the Program A application forms.

2.2.1. Biographical Questionnaire

Prior to the first round of interviews, participants were asked to complete a short biographical questionnaire on their background, including nationality, L1, L2, and L3, as well as the levels of L2 and L3.

2.2.2. Motivation Graphs

Based on previous studies [12,32,33], motivation graphs were collected to elicit the participants’ motivational trajectories from their enrolment in Program A to the interview. The participants drew two lines to express their motivation to learn English and Japanese, respectively. The grid was divided into semesters and the motivation scale ranged from 0 to 5.

2.2.3. Interviews

Among methods of collecting qualitative data, interviewing is used most frequently (Dörnyei, 2007; Ushioda, 2019). Interview expectations for participants’ roles and etiquette are typically shared [34]. It also helps achieve a variety of research aims with its flexibility [27]. Finally, it allows a researcher to explore “self-and-identify strivings” [19,30] (p. 667). Interviewing was considered the most appropriate tool regarding the participants’ diverse backgrounds and the study objectives Therefore, primary data were collected from semi-structured interviews.

Following Fukui and Yashima [12] and Dörnyei [27], the interview for each participant was conducted twice. First, a preliminary round of interviews was conducted. Based on analyses of these interviews, a second round was conducted. The results introduced in this paper were mainly from the second round. Based on Fukui and Yashima [12], questions included “Why did you decide to study in Japan?”, “Why did you decide to study in Program A?”, “What reason(s) and/or incident(s) related to motivational ups and downs did you feel in your English and Japanese learning?”, and “What are you planning to do after graduation?”. During the first round of interviews, Iori shared that she had been sick during the previous year and had to prioritize treatment over her studies. Silvia identified herself as an L1 English speaker, so did not learn or try to improve her English proficiency. To answer the research questions, especially RQ2 (i.e., are the motivations to learn English, Japanese and policy studies related?), those two participants were excluded from the second round of interviews. Therefore, data from Gabi, Heidi, and Pia will be discussed in this paper, while Silvia and Iori’s stories will be referred to when appropriate.

2.2.4. Program A Application Forms

After the first round of interviews, the researcher realized that the students’ language learning experiences were more diverse than anticipated. To ensure the second round of interviews was more effective, their Program A application forms, including a record of their learning experience (e.g., which schools they attended and their primary language of instruction), were collected.

2.3. Procedure

All the data were collected with the participants’ consent. They also understood that they could withdraw from the study at any time. The author conducted all interviews. Since I was a faculty member and was teaching Heidi, Pia and Silvia, they were carefully informed that the participation and their answers would not affect their grades in any way. Each interview was conducted separately and face-to-face in the author’s office. The duration of both rounds of each interview lasted between 60 to 80 min, were conducted in English, and audio was recorded.

2.4. Analyses

The data analysis method was based in part on the grounded theory approach [35]. Spoken data were transcribed and reread. Data were then coded sentence by sentence or based on units of meaning. The transcripts were read again and concepts were created to describe each code. Finally, concepts with a similar meaning were grouped and developed into categories. As the aim of the study was not to postulate a theory, data from each participant were analyzed separately. Data not related to the research questions were excluded (e.g., experiences with COVID-19). The results section applied the narrative inquiry approach to investigating a phenomenon [36]. This means that narrative was used to explore the content of the narratives—what they tell us about their experiences.

3. Results

The analysis of the data elicited before and during SA in Program A yielded 30 categories related to the RQs for Gabi, with 105 codes under these categories. For Heidi, 30 categories were found, with 110 codes. For Pia, 31 categories were identified, with 136 codes. The participants had some commonalities and differences. From the demographic information provided, it was evident that everyone had rich English learning experiences. Further, they had little to no knowledge about policy science before enrollment. Heidi and Pia had ample international contacts as they grew up, but neither of them had any specific reasons for applying to Program A. Each case is discussed according to their perception of the significance of Japanese for academic purposes. Categories are identified in bold and the intelligent verbatim transcription technique [37] is applied in the following section.

3.1. Case 1-Gabi: Japanese Is as Important as English to Learning Policy Studies

Sustained High Motivation to Learn Japanese

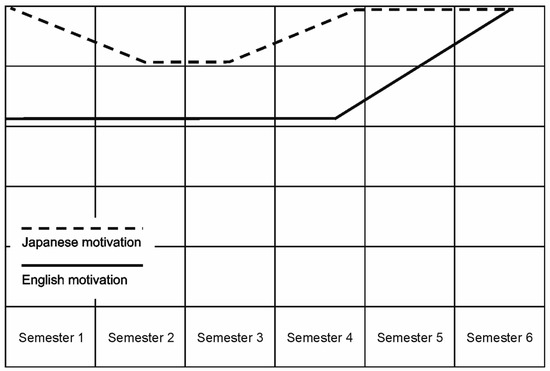

Gabi’s motivation to learn Japanese (see Figure 1) remained elevated. Table 2 shows the categories cited in this section.

Figure 1.

Gabi’s motivation graph during SA.

Table 2.

Main categories for Gabi.

For Gabi, acquiring Japanese was essential for SA as she wanted to secure a job in a Japanese company based in China. The following excerpt describes competitiveness in the Chinese job market and how English is losing its premium value [12].

| Excerpt 1. | |

| Gabi | If you could speak Japanese, you may be better than others. You may have more opportunities to get a job in some Japanese companies, other than just normal Chinese companies. |

| Interviewer | Is English not enough? |

| Gabi | It’s not enough. Nowadays in China, it’s popular for some parents to have their children learn a variety of languages. So, they are more competitive than others. It’s a kind of social phenomena in China. I think learning more languages is better. |

Gabi wanted to learn an L3 spoken by a small population, such as Japanese or Korean. She chose Japanese owing to her positive attitude toward Japanese culture and integrativeness [38].

| Excerpt 2. | |

| Gabi | I like the atmosphere. Maybe it’s kind of a stereotype, but most of us think the Japanese are serious, like always serious about everything. So, I think it may be the same at the university. We can learn more than in Korea. |

| Excerpt 3. | |

| Gabi | In Program A, we can learn English, Japanese, and policy studies. So, I think it’s better [than being in a language major]. |

| Interviewer | Why do you think it is better? |

| Gabi | Because I think language is just a tool to communicate. |

Since enrollment, she has been highly motivated to learn Japanese for academic purposes. She has taken many extra Japanese classes, spent 30 min to one hour in studying Japanese every day, and taken the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT). At the time of her interview, she had already passed the highest grade of JLPT and was still trying to improve her score to conduct research in Japanese, be able to participate in Japanese discussions at graduate school, and obtain a scholarship. She clearly visualized herself speaking fluent Japanese as a graduate student (ideal L3 self) which enhanced her motivation.

| Excerpt 4. | |

| Gabi | In a graduate school, the classes might be taught in Japanese. And when the discussions are conducted, there would be a lot of Japanese students in the group. I may have to discuss in Japanese, so I need to learn Japanese before I go to graduate school. |

Meanwhile, she put learning English on hold [6].

| Excerpt 5. | |

| Gabi | I started to learn English from primary school, but I started to learn Japanese just from university, so maybe the time (that I spent to learn Japanese) is not long enough, so I need to put more time into learning Japanese. |

Regarding motivation to learn English, in fact, Gabi did not take any extra EAP courses or take extra time to learn English. However, she still valued learning English as she was aware that improving her English proficiency was necessary to becoming a university professor abroad, which was her ideal job at that time. Her choice to prioritize learning Japanese over English confirms the conclusions of previous studies that learning two languages at the same time is demanding (e.g., Fukui & Yashima, 2021); the motivations to learn L2 and L3 thus interact with each other depending on the contexts [6]. As can be seen in Gabi’s case, the motivations to learn Japanese, English, and the academic discipline are all interrelated.

3.2. Case 2-Heidi: English Was More Important Than Japanese to Learn Policy Studies

3.2.1. No Specific Reasons, but Excited about SA

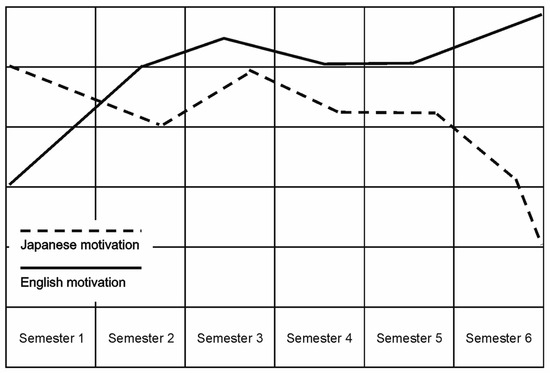

Unlike Gabi, Heidi’s motivation fluctuated during her time in Program A (see Figure 2). The categories cited in this section are listed in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Heidi’s motivation graph during SA.

Table 3.

Main categories for Heidi.

In fact, she did not have a specific aim when applying for Program A. During the first round of the interview, she said that she learned about Program A at an SA fair her teacher required her to attend and signed up for its mailing list to obtain a novelty item. While she had no knowledge about either policy studies or Japan, she enrolled in Program A owing to her parents’ encouragement and scholarship opportunities.

| Excerpt 6. | |

| Heidi | I thought Japan was a country like Singapore, you know, like the ones who speak English, like people speak English. |

She did not know what policy studies were even a year after enrollment.

| Excerpt 7. | |

| Heidi | I had no idea what policy studies was. And I still wasn’t quite sure about policy studies during the first two semesters […] every time my family asked me, “So what are you studying?” I answered, “I don’t know, I have no idea.” |

However, she has a high positive attitude toward communicating with others and high English proficiency. This could be due to the international environment in which she was raised; Heidi’s mother raised her as bilingual and sent her to English language and bilingual schools when she was six. Her family also hosted international volunteers when she was in high school. This ensured that Heidi had constant opportunities to use English in authentic situations. Although she was not particularly interested in Program A or Japan, her extensive exposure to English and intercultural communication helped her prepare for SA. Her openness to a new culture and willingness to communicate in L3 [9] are observed in the following excerpt, which shows that she was initially quite excited to learn Japanese.

| Excerpt 8. | |

| Heidi | I was excited, really excited to learn Japanese, a new language. Yeah, to study and to be able to communicate with the people here. |

3.2.2. The Interchanging Degree of Motivation between Learning Japanese and English

In contrast, her motivation to learn English at that time was low. She was tired of studying English since she had taken various standardized exams (e.g., TOEFL, the exit exam in Indonesia) and thought her English was already adequate. However, her motivation to learn English was boosted through communication with other students in Program A when she realized that her English was not as perfect as she thought and could be improved further.

| Excerpt 9. | |

| Heidi | I felt, okay, I have enough English, but then I started to see my friends from all around the world with many different accents and I started to think like, it’s not enough, like my English is not enough. I need to know more slang, more phrases, more accents, and be more familiar with accents. |

Her motivation to learn EAP was enhanced as her courses became more advanced.

| Excerpt 10. | |

| Heidi | The more I study policy studies, the more I should improve my English, like I have to improve. […] Yeah. When I read journal articles, I feel like I need to improve my skills to read quickly in English. |

She also valued Japanese for academic purposes to fully comprehend the research conducted in Japan thoroughly.

| Excerpt 11. | |

| Heidi | When I study policy studies in Japan, like case studies in Japan, I feel, oh, I don’t have enough Japanese to understand what’s going on in Japan. |

However, she had given up learning Japanese at the time of the interview. Although she was excited about learning Japanese in the beginning, she was getting bad grades, failing the JLPT, and struggling with learning kanji (Chinese characters). Her negative learning experience gradually decreased her motivation to learn the language and when only a year of Program A remained, she lost her motivation completely.

| Excerpt 12. | |

| Heidi | I was like, okay, I’m going to give up on Japanese. I don’t think it’s my thing. |

Silvia also mentioned that she quit learning Japanese because of her negative learning experience (e.g., she barely passed the kanji classes although she worked very hard). Hence, this indicates that learning experience significantly affects L3 motivation and it is common for students to lose their motivation to learn Japanese over time due to negative learning experiences.

As noted, Heidi perceived her motivation to learn English, Japanese, and policy studies to be interrelated although her motivation to learn Japanese and policy studies was weaker than her motivation to learn English and policy studies.

3.3. Case 3-Pia: Japanese Is Unrelated to Learning Policy Studies

Finally, Pia enrolled in Program A because it was the only option for attending university. Table 4 lists the main categories for Pia. She had not intended to SA, but her father convinced her to pursue a degree in Japan when she failed the university entrance exam in Korea. Although she applied to three ETPs in Japan, she was only accepted to Program A. Consequently, unlike Gabi or Heidi, Pia did not mention any goals or excitement about SA. Like Heidi, she was not interested in either Japanese or policy studies. However, she had plentiful intercultural experience and high English proficiency as she had lived in the United States for a year at the age of 11 due to her father’s job.

Table 4.

Main categories for Pia.

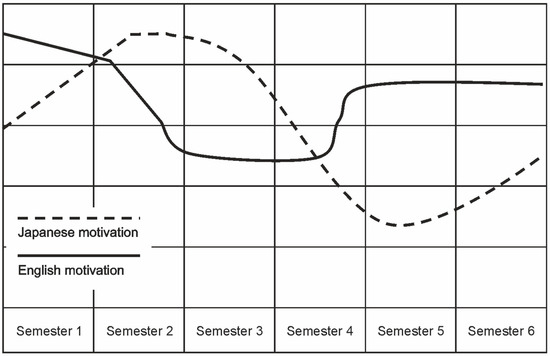

After enrollment, Pia felt that Japanese classes were easy. She enjoyed them and obtained good grades. This positive learning experience enhanced her motivation to learn Japanese (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pia’s motivation graph during SA.

However, her motivation to learn Japanese decreased when she fulfilled the prerequisite to graduate, although she felt obligated to be fluent in the native language of her SA country. It could be because she did not have a clear image of the person she wanted to become as a Japanese speaker [11] or her perception that learning Japanese is related to her academic learning.

| Excerpt 13. | |

| Pia | English and my academic studies are related because I study everything in English. But, Japanese, I don’t think it’s related. It’s independent. |

Regarding her motivation to learn English, it decreased in the second semester when she realized that “nativeness” was less important than she expected.

| Excerpt 14. | |

| Pia | After the first semester, I realized that it’s not that important. Perfect English, of course, it matters. But the contents matter more. I kind of lost my interest in academic English. |

| Interviewer | How did you realize it was not that important? |

| Pia | Well, in Program A, there are some students whose mother tongue is English. I’m 100% sure that they wrote papers in more perfect English than me, but I had better scores. I had better grades, and it seems like maybe it matters but it’s not as important as I expected |

However, while working on her graduation thesis, she realized that she found reading and writing English far more demanding than writing and reading Korean. This enhanced her motivation to learn EAP.

| Excerpt 15. | |

| Pia | Even though I know that it [perfect English] is not what matters the most, English is still an important part of my academic studies. I feel pressure like when I have to read like 30 pages of a journal article. In Korean, I read really, really fast […], but in English, I’m really slow. I feel pressured [and think] “how can I read all of this?”. |

While Program A was not her initial desired destination, Pia’s overall learning experience was positive. She even expressed that since she wanted to become a university professor, Program A, which let her focus on academic learning, was a better choice than going to a Korean university.

| Excerpt 16. | |

| Pia | I will recommend Program A [to my friends] because—in Korea, most of Korean university students work harder to get a job instead of going to graduate school. Most of the classes, are not academic enough […]. But, in Program A, you have a deeper understanding of the content that we study than in Korea. |

4. Discussion

This study tried to uncover the initial motivation and relationship between different kinds of motivation in an ETP. Regarding RQ1 (Why do international students choose an ETP in Japan?), the results suggested that some students chose Program A to live in Japan, but not everyone had clear SA aims when applying to the program. Gabi chose Japanese as her L3 because she had a positive affective disposition toward the Japanese community (i.e., integrativeness) [38] and culture. Iori also chose Program A because she wanted to learn about Japanese culture and the language, as she was half-Japanese. Heidi and Pia, meanwhile, did not have any specific goals for SA. Silvia also said that she was not interested in either Japan or policy studies but chose Program A as she obtained a full four-year scholarship. Previous surveys were designed based on the hypothesis that international students have clear intentions to study in Japan [26]. However, the current study captures a different reality and suggests that the expansion of EMI has led to an increase in student mobility; thus, SA no longer requires considerable courage or determination, especially SA in the same region (e.g., Korean students studying in Japan). The participants’ biographical data and interviews show that they grew up in environments with ample experiences of learning English and intercultural contacts. Even though Silvia had not gone abroad previously, her father was working in England. In other words, recruiting students who tend to relate to the international community (i.e., international posture) [39] could be quite beneficial regardless of the academic discipline of the ETPs.

Regarding RQ2 (Are the motivations to learn English, Japanese and policy studies related? If so, how?), the results indicated a strong relationship between participants’ motivation to learn English and the content of their academic program, confirming the results of a previous study in EMI [40]. However, the relationship between motivation to learn Japanese and the program’s academic content is more complex and differs among participants. Existing research on L3 motivation usually reports that L3 learning “typically takes place in the shadow of Global English” [5] (p. 457). Thus, studies often focus on the negative impact of L2 (English) on L3 learning [1,2]. However, Gabi maintained high motivation to learn Japanese for academic purposes, which was supported by her positive learning experience, clear L3 ideal self, and L3 ought-to self [11]. Although Heidi lost her motivation to learn Japanese due to negative learning experiences, she still thought Japanese was important to understanding academic research based in Japan. Heidi’s narratives support previous research results. L2 learning experiences is the strongest predictor in the L2MSS (i.e., ideal L2 self, ought-to L2 self, and L2 learning experience) [18,41,42,43]. Contrastingly, Pia perceived Japanese as insignificant for her academic learning even though she enjoyed her Japanese classes. In fact, Pia saw taking Japanese classes as an easy way to sustain her high GPA while Silvia quit taking Japanese classes because they were lowering her GPA; this suggests that GPA affects students’ choice of courses [43]. Pia’s perspective of Japanese being unrelated to academic learning is in line with Simic et al., [8] whose study reported that “harmony with society” (p. 118) is a major reason that international students in a Japanese ETP learned the Japanese language while considering it largely unassociated with academic success. As their ultimate SA goal is to obtain a degree, the more fluent they become in English, the less motivated they become to communicate in Japanese. This study pointed out that current ETPs remove the language barrier to studying in Japan but do not inspire students to learn the Japanese language and culture.

The study has certain limitations, such as the small sample size. Moreover, two participants were excluded. One (Iori) had a health issue. The other (Silvia) was excluded due to her perception of her L1. Furthermore, participation in the study was voluntary. Therefore, some participants could have been more motivated than others. Although more research must be conducted to confirm the study results, its findings suggest that international orientation and L2 and L3 motivations seem interrelated in the context of ETPs. In addition, one benefit derived from this study involved a student with a vivid ideal L3 self, sustaining her high L3 motivation even in an ETP context, in which Global English is valued significantly. Thus, a possibility exists that L3 learning motivation can be sustained and enhanced if the language classes provide positive learning experiences and help students visualize their ideal selves as L3 speakers.

Funding

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (22K00724).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results, discussion and conclusions of this article are available at DOI: 10.17632/2284g37bnt.1. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank all the participants in this study. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and input.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Csizér, K.; Dörnyei, Z. Language Learners’ Motivational Profiles and Their Motivated Learning Behavior. Lang. Learn. 2005, 55, 613–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A. Contexts of possibility in simultaneous language learning: Using the L2 Motivational Self System to assess the impact of global English. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2010, 31, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A. Examining the impact of L2 English on L3 selves: A case study. Int. J. Multiling. 2011, 8, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizér, K.; Illés, É. Helping to Maximize Learners’ Motivation for Second Language Learning. Lang. Teach. Res. Q. 2020, 19, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Al-Hoorie, A.H. The Motivational Foundation of Learning Languages Other Than Global English: Theoretical Issues and Research Directions. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siridetkoon, P.; Dewaele, J.-M. Ideal self and ought-to self of simultaneous learners of multiple foreign languages. Int. J. Multiling. 2017, 15, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simic, M.; Tanaka, T.; Hasegawa, Y. Usage of Japanese as a Third Language among International Students in Japan. J. Int. Stud. 2006, 11, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Simic, M.; Tanakai, T.; Yashima, T. Willingness to Communicate in Japanese as a Third Language among International Students in Japan. Multicult. Relat. 2007, 4, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Dörnyei, Z.; Clément, R.; Noels, K.A. Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2 Confidence and Affiliation. Mod. Lang. J. 1998, 82, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z. The L2 Motivational Self System. In Motivation, Language Identity, and the L2 Self; Dörnyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z. The Psychology of the Language Learner Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, H.; Yashima, T. Exploring Evolving Motivation to Learn Two Languages Simultaneously in a Study-Abroad Context. Mod. Lang. J. 2021, 105, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, G.; Teng, F. Exploring complexity in L2 and L3 motivational systems: A dynamic systems theory perspective. Lang. Learn. J. 2019, 49, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen-Freeman, D. Complexity Theory. In Theories in Second Language Acquisition; VanPatten, B., Williams, J., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Boo, Z.; Dörnyei, Z.; Ryan, S. L2 motivation research 2005–2014: Understanding a publication surge and a changing landscape. System 2015, 55, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S. (Ed.) The Multilingual Turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and Bilingual Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, L. SLA for the 21st Century: Disciplinary Progress, Transdisciplinary Relevance, and the Bi/multilingual Turn. Lang. Learn. 2013, 63 (Suppl. S1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hoorie, A.H. The L2 motivational self system: A meta-analysis. Stud. Second. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2018, 8, 721–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Ushioda, E. Teaching and Researching Motivation, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden, J. English as a Medium of Instruction-a Growing Global Phenomenon; British Council: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.A. English-medium teaching in European higher education. Lang. Teach. 2006, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, I.; Fenton-Smith, B.; Humphreys, P. EMI Issues and Challenges in Asia-Pacific Higher Education: An Introduction. In English Medium Instruction in Higher Education in Asia-Pacific: From Policy to Pedagogy; Fenton-Smith, B., Humphreys, P., Walkinshaw, I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Macaro, E.; Curle, S.; Pun, J.; An, J.; Dearden, J. A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Lang. Teach. 2017, 51, 36–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, D. The relationship between motivation, gender, L1 and possible selves in English-medium instruction. Int. J. Multiling. 2015, 13, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heigham, J. Center Stage but Invisible: International Students in an English-Taught Program. In English-Medium Instruction in Japanese Higher Education: Policy, Challenges and Outcomes; Bradford, A., Brown, H., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2018; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, N.; Curle, S. “I Just Wanted to Learn Japanese and Visit Japan”: The Incentives and Attitudes of International Students in English-Medium Instruction Programmes in Japan. Int. J. Lang. Stud. 2022, 16, 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methodologies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhuizen, G. Number of participants. Lang. Teach. Res. 2014, 18, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushioda, E. A Person-in-Context Relational View of Emergent Motivation and Identity. In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self; Dörnyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ushioda, E. Researching L2 Motivation: Past, Present and Future. In The Palgrave Handbook of Motivation for Lanugage Learning; Lamb, M., Csizér, K., Henry, A., Ryan, S., Eds.; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2019; pp. 661–682. [Google Scholar]

- Ushioda, E. Researching L2 Motivation: Re-Evaluating the Role of Qualitative Inquiry, or the ‘Wine and Conversation’ Approach. In Contemporary Language Motivation Theory: 60 Years since Gardner and Lambert (1959); Al-Hoorie, A.H., MacIntyre, P.D., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2020; pp. 194–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T.; Arano, K. Understanding EFL Learners’ Motivational Dynamics: A Three-Level Model from a Dynamic Systems and Sociocultural Perspective. In Motivational Dynamics in Language Learning; Dörnyei, Z., MacIntyre, P.D., Henry, A., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 285–314. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, L.; Dörnyei, Z.; Alastair, H. Learner Archetypes and Signature Dynamics in the Language Classroom: A Retrodictive Qualitative Modelling Approach to Studying L2 Motivation. In Motivational Dynamics in Language Learning; Dörnyei, Z., MacIntyre, P.D., Henry, A., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 238–259. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.L.; Crabtree, B.F. Depth of Interviewing. In Doing Qualitative Research; Crabtree, B.F., Miller, W.L., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1999; pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhuizen, G.; Consoli, S. Pushing the edge in narrative inquiry. System 2021, 102, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, M. Contrastive analysis of Turkish and English in Turkish EFL learners’ spoken discourse. Int. J. Engl. Stud. 2016, 16, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T. International Posture and the Ideal L2 Self in the Japanese EFL Context. In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self; Dörnyei, Z., Ushioda, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, N.; Yashima, T. Motivation in English Medium Instruction Classrooms from the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory and the Ideal Self. JACET J. 2017, 61, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T.; Nishida, R.; Mizumoto, A. Influence of Learner Beliefs and Gender on the Motivating Power of L2 Selves. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101, 691–711. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, M. A Self System Perspective on Young Adolescents’ Motivation to Learn English in Urban and Rural Settings. Lang. Learn. 2012, 62, 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A. Toward a Typology of Implementation Challenges Facing English-Medium Instruction in Higher Education: Evidence from Japan. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2016, 20, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).