Evaluating a Smartphone App for University Students Who Self-Harm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Intervention

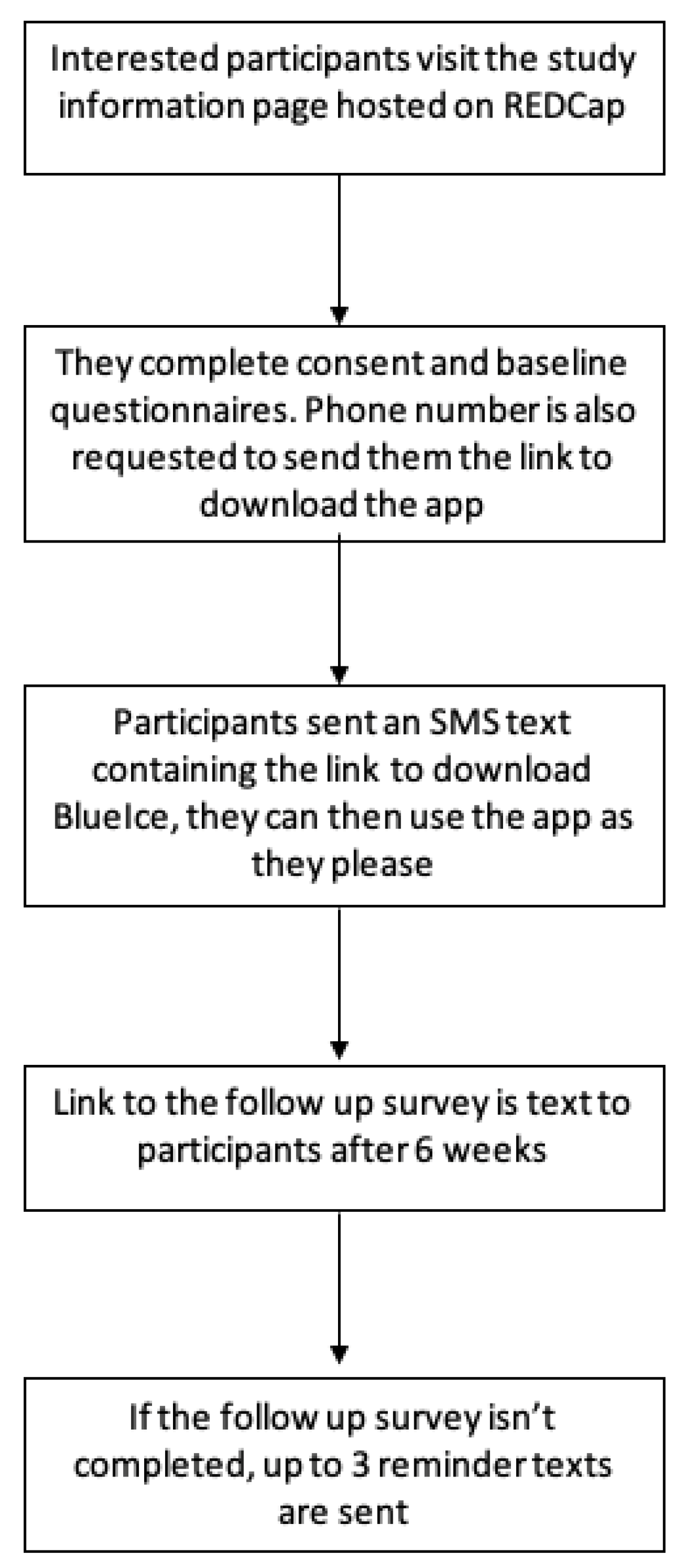

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Measures

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results therapy, as they Are believed to Be important

3.1. Post-Use Outcomes

3.2. Acceptability of BlueIce

3.3. Implementation

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Study Questionnaire

- 1.

- What is your age?

- 2.

- What gender do you identify as?

- Male

- Female

- Non-binary

- Prefer not to say

- Other

- a.

- If you selected other, please specify:

- 3.

- Do you identify as transgender?

- Yes

- No

- Prefer not to say

- 4.

- What best describes your sexuality?

- Gay

- Lesbian

- Bisexual

- Heterosexual

- Pansexual

- Queer

- Prefer not to say

- Other

- a.

- If you selected other, please specify:

- 5.

- What is your ethnicity?

- White

- Asian/Asian British

- Black/African/Caribbean/Black British

- Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups

- Prefer not to say

- Other

- a.

- If you selected Other, please specify:

- 6.

- What is your level at university?

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Doctoral

- Prefer not to say

- Other

- If you selected Other, please specify:

- 7.

- How did you hear about BlueIce?

- University website

- Poster around campus

- Facebook

- Twitter

- Word of mouth

- University wellbeing services

- Other

- If you selected Other, please specify:

- 8.

- Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems?

| Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

| Not being able to stop or control worrying | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

| Little interest or pleasure in doing things | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

| Feeling down, depressed or hopeless | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

- 9.

- Have you ever hurt yourself on purpose in any way (e.g., by taking an overdose of pills, or by cutting yourself)?

- Yes

- No

- a.

- If yes, how many times have you done this in the last 2 weeks? Please mark one box only.

- No times

- Once

- 2–5 times

- 6–10 times

- More than 10 times

- b.

- When was the last time you hurt yourself on purpose? Please mark one box only.

- In the last week

- More than a week ago but in the last 2 weeks

- More than 2 weeks ago but in the last 6 weeks

- More than 6 weeks ago

- c.

- When you last self-harmed, did you need to seek medical advice?

- Yes, but I did not seek medical advice

- Yes, and I did seek medical advice

- No

- 10.

- Please rate your overall average urge or desire to harm yourself in the last two weeks.

- 1.

- Never had the urge to self-harm

- 2.

- Rarely had the urge to self-harm

- 3.

- Sometimes had the urge to self-harm

- 4.

- Often had the urge to self-harm

- 5.

- Had the urge to self-harm nearly all the time

- 11.

- Over the past month have you felt that life was not worth living?

- Yes

- No

- 12.

- When faced with problems or situations that are stressful or distressing, to what extent:

| Do you feel confident or certain that you could deal with them? | 1 Not at all | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Somewhat | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Completely |

| Do you try to deal with any emotional upset, without self-harming? | 1 Not at all | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Somewhat | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Completely |

| Do you try to directly confront and deal with them? | 1 Not at all | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Somewhat | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Completely |

| Do you try and ignore or not think about them? | 1 Not at all | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Somewhat | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Completely |

| Do you try to think about them in a more positive way? | 1 Not at all | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Somewhat | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Completely |

- 13.

- Have you used BlueIce over the last 6 weeks?

- Yes

- No

- a.

- If no, were there any reasons why you didn’t use it? (free text response)

- b.

- If Yes—How many times have you used BlueIce?(Sliding scale) Never Rarely Sometimes Often

- 14.

- Were there any times that you used BlueIce and it stopped you from harming yourself?

- Yes

- No

- a.

- If no, why do you think it did not stop you from harming yourself? (free text response)

- b.

- If Yes, how many times did it stop you from harming yourself?(Sliding scale) Never Rarely Sometimes Often

- c.

- Why do you think BlueIce stopped you from harming yourself?(Free text response)

- 15.

Do you think other students could benefit from BlueIce? 1

Definitely not2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

DefinitelyWas BlueIce helpful for you? 1

Definitely not2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Definitely- 16.

- Is there any other feedback you would like to give about the BlueIce app or the impact it may have had on your mental health and self-harm? (free text response)

References

- Taliaferro, L.A.; Muehlenkamp, J.J. Risk Factors Associated with Self-injurious Behavior Among a National Sample of Undergraduate College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2015, 63, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallman, H.M. Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Aust. Psychol. 2010, 45, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.J.; James, R.; Magistro, D.; Donaldson, J.; Healy, L.C.; Nevill, M.; Hennis, P.J. Mental health and movement behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in UK university students: Prospective cohort study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 19, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swannell, S.V.; Martin, G.E.; Page, A.; Hasking, P.; John, N.J.S. Prevalence of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Nonclinical Samples: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivertsen, B.; Hysing, M.; Knapstad, M.; Harvey, A.G.; Reneflot, A.; Lønning, K.J.; O’Connor, R.C. Suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm among university students: Prevalence study. BJPsych Open 2019, 5, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, P.; Arundell, L.-L.; Saunders, R.; Matthews, H.; Pilling, S. The efficacy of psychological interventions for the prevention and treatment of mental health disorders in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 280, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollust, S.E.; Eisenberg, D.; Golberstein, E. Prevalence and Correlates of Self-Injury Among University Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 56, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharsati, N.; Bhola, P. Patterns of non-suicidal self-injurious behaviours among college students in India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 61, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; McLafferty, M.; Ennis, E.; Lapsley, C.; Bjourson, T.; Armour, C.; Murphy, S.; Bunting, B.; Murray, E. Socio-demographic, mental health and childhood adversity risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviour in college students in Northern Ireland. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.; Eckenrode, J.; Silverman, D. Self-injurious Behaviors in a College Population. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliffe, B.; Stallard, P. University students’ experiences and perceptions of interventions for self-harm. J. Youth Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyz, E.K.; Ba, A.G.H.; Eisenberg, D.; Kramer, A.; King, C.A. Self-reported Barriers to Professional Help Seeking Among College Students at Elevated Risk for Suicide. J. Am. Coll. Health J. ACH 2013, 61, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, J.C.; Fox, K.R.; Franklin, C.R.; Kleiman, E.M.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; Hooley, J.M.; Nock, M.K. A brief mobile app reduces nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injury: Evidence from three randomized controlled trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooth. The State of the Nation’s Mental Health. Kooth Pulse 2021. 2021. Available online: https://explore.kooth.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Kooth-Pulse-2021-Report.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Davies, E.B.; Morriss, R.; Glazebrook, C. Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattie, E.G.; Adkins, E.C.; Winquist, N.; Stiles-Shields, C.; Wafford, Q.E.; Graham, A.K. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression, Anxiety, and Enhancement of Psychological Well-Being Among College Students: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.A.; Jung, M.E. Evaluation of an mHealth App (DeStressify) on University Students’ Mental Health: Pilot Trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.L.; Shochet, I.; Stallman, H. Universal online interventions might engage psychologically distressed university students who are unlikely to seek formal help. Adv. Ment. Health 2010, 9, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Bauer, S.; Salter, A.; Bennett, L.; Seilhamer, R. Changing Mobile Learning Practices: A Multiyear Study 2012–2016. 2018. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2018/4/changing-mobile-learning-practices-a-multiyear-study-2012-2016 (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Cliffe, B.; Stokes, Z.; Stallard, P. The Acceptability of a Smartphone App (BlueIce) for University Students Who Self-harm. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cliffe, B.; Stallard, P. The Acceptability, Safety, and Effects of a Smartphone Application for University Students Who Self-Harm: An Open Study. JMIR Prepr. 2022. Available online: https://preprints.jmir.org/preprint/40492 (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Stallard, P.; Porter, J.; Grist, R. A Smartphone App (BlueIce) for Young People Who Self-Harm: Open Phase 1 Pre-Post Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallard, P.; Porter, J.; Grist, R. Safety, Acceptability, and Use of a Smartphone App, BlueIce, for Young People Who Self-Harm: Protocol for an Open Phase I Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care: Prevalence, Impairment, Comorbidity, and Detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, F.; Manea, L.; Trepel, D.; McMillan, D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2, a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumosleh, J.M.; Jaalouk, D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students—A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löwe, B.; Kroenke, K.; Gräfe, K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 58, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.P.; Rockhill, C.; Russo, J.E.; Grossman, D.C.; Richards, J.; McCarty, C.; McCauley, E.; Katon, W. Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a Brief Screen for Detecting Major Depression among Adolescents. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e1097–e1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, A.; Golding, J.; Macleod, J.; Lawlor, D.A.; Fraser, A.; Henderson, J.; Molloy, L.; Ness, A.; Ring, S.; Smith, G.D. Cohort Profile: The ‘Children of the 90s’—The index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, E.; Sayal, K.; Townsend, E. Functional Coping Dynamics and Experiential Avoidance in a Community Sample with No Self-Injury vs. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Only vs. Those with Both Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Suicidal Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, I.; Tingley, J.; Taylor, G.; Medina-Lara, A.; Rhodes, S.; Stallard, P. Beating Adolescent Self-Harm (BASH): A randomised controlled trial comparing usual care versus usual care plus a smartphone self-harm prevention app (BlueIce) in young adolescents aged 12–17 who self-harm: Study protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliffe, B.; Tingley, J.; Greenhalgh, I.; Stallard, P. mHealth Interventions for Self-Harm: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.; Sharma, V.; Fortune, S.; Wadman, R.; Churchill, R.; Hetrick, S. Adapting a codesign process with young people to prioritize outcomes for a systematic review of interventions to prevent self-harm and suicide. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C.; Fox, F.; Redwood, S.; Davies, R.; Foote, L.; Salisbury, N.; Williams, S.; Biddle, L.; Thomas, K. Measuring outcomes in trials of interventions for people who self-harm: Qualitative study of service users’ views. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honary, M.; Bell, B.; Clinch, S.; Vega, J.; Kroll, L.; Sefi, A.; McNaney, R. Shaping the Design of Smartphone-Based Interventions for Self-Harm. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A.L.; Gratz, K.L. Freedom from Self-Harm: Overcoming Self-Injury with Skills from DBT and Other Treatments; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, L.; Campbell, A.; Sethi, S.; O’Dea, B. Comparative Randomized Trial of an Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Program and an Online Support Group for Depression and Anxiey. J. Cyberther. Rehabil. 2011, 4, 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R.D.; Buckey, J.C.; Zbozinek, T.D.; Motivala, S.J.; Glenn, D.E.; Cartreine, J.A.; Craske, M.G. A randomized controlled trial of a self-guided, multimedia, stress management and resilience training program. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Amaya, M.; Szalacha, L.A.; Hoying, J.; Taylor, T.; Bowersox, K. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Effects of the COPE Online Cognitive-Behavioral Skill-Building Program on Mental Health Outcomes and Academic Performance in Freshmen College Students: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 28, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, J.E.; Richards, D.; Palmer, R.; Coudray, C.; Hofmann, S.G.; Palmieri, P.A.; Frazier, P. Supported Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Programs for Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in University Students: Open, Non-Randomised Trial of Acceptability, Effectiveness, and Satisfaction. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e11467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Bergen, H.; Mahadevan, S.; Casey, D.; Simkin, S. Suicide and deliberate self-harm in Oxford University students over a 30-year period. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, C.J.; Rahim, W.A.; Rowe, R.; O’Connor, R.C. An exploratory randomised trial of a simple, brief psychological intervention to reduce subsequent suicidal ideation and behaviour in patients admitted to hospital for self-harm. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelraheem, M.; McAloon, J.; Shand, F. Mediating and moderating variables in the prediction of self-harm in young people: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic | Category | Baseline Sample (N = 80) | Follow-Up Sample (N = 27) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender identity | |||

| Female | 58 (72.5%) | 20 (74.1%) | |

| Male | 12 (15%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Non-binary | 5 (6.3%) | 0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 5 (6.3%) | 3 (11.1%) | |

| Transgender | |||

| No | 72 (90%) | 25 (92.6%) | |

| Yes | 5 (6.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (3.8%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Sexuality | |||

| Heterosexual | 37 (46.3%) | 9 (33.3%) | |

| Bisexual | 13 (16.3%) | 7 (25.9%) | |

| Lesbian | 8 (10%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Queer | 7 (8.8%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Pansexual | 3 (3.8%) | 2 (7.4%) | |

| Gay | 2 (2.5%) | 0 | |

| Other—Demisexual | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Other—Unsure | 1 (1.3%) | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (1.3%) | 0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 7 (8.8%) | 3 (11.1%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 61 (76.3%) | 20 (74.1%) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 10 (12.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 5 (6.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Other—Middle Eastern | 2 (2.5%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Other—Latin American | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Other—North African | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| University level | |||

| Undergraduate | 68 (85%) | 21 (77.8%) | |

| Postgraduate | 5 (6.3%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Doctoral | 5 (6.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (2.5%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| Item | Answer | Baseline Sample n (%) | Follow-Up n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime self-harm | Yes | 57 (71.3%) | 18 (66.7%) |

| No | 23 (28.7%) | 9 (33.3%) | |

| Self-harm frequency within last 2 weeks | 0 | 34 (59.6%) | 9 (50%) |

| 1 | 7 (12.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | |

| 2–5 | 14 (24.6%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| 6+ | 2 (3.5%) | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Last self-harm episode | In the last week | 15 (26.8%) | 6 (33.3%) |

| Between 1 and 2 weeks ago | 7 (12.5%) | 3 (16.7%) | |

| Between 2 and 6 weeks ago | 15 (26.8%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| More than 6 weeks ago | 19 (33.9%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| Self-harm urges within last 2 weeks | Never had the urge | 22 (27.8%) | 10 (37%) |

| Rarely had the urge | 20 (25.3%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| Sometimes had the urge | 20 (25.3%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Often had the urge | 15 (19%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| Had the urge nearly always | 2 (2.5%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Medical advice needed during last self-harm | No | 50 (89.3%) | 16 (88.9%) |

| Yes but did not seek it | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Yes and it was sought | 4 (7.1%) | 1 (5.6%) | |

| Suicidal thoughts in past month | No | 32 (40%) | 14 (51.9%) |

| Yes | 48 (60%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Items | Baseline M(SD) | Follow-Up M(SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 5.44 (1.81) | 4.52 (1.97) |

| Depression | 5.37 (1.80) | 4.52 (1.60) |

| Self-harm urges | 1.85 (1.29) | 1.35 (1.33) |

| Self-harm acts | 1.06 (1.25) | 1.06 (1.25) |

| Suicidal ideation | 0.62 (0.50) | 0.50 (0.51) |

| Coping self-efficacy | 4.58 (1.86) | 5.65 (1.74) |

| Reappraisal | 4.08 (2.00) | 5.31 (2.21) |

| Emotion regulation | 6.69 (2.62) | 7.69 (2.24) |

| Active coping | 4.56 (2.00) | 5.60 (1.92) |

| Avoidant coping | 6.08 (2.15) | 6.04 (2.62) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cliffe, B.; Stallard, P. Evaluating a Smartphone App for University Students Who Self-Harm. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040394

Cliffe B, Stallard P. Evaluating a Smartphone App for University Students Who Self-Harm. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(4):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040394

Chicago/Turabian StyleCliffe, Bethany, and Paul Stallard. 2023. "Evaluating a Smartphone App for University Students Who Self-Harm" Education Sciences 13, no. 4: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040394

APA StyleCliffe, B., & Stallard, P. (2023). Evaluating a Smartphone App for University Students Who Self-Harm. Education Sciences, 13(4), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040394