Unlocking Emotional Aspects of Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Identity through Photovoice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Teachers’ Professional Identity and Emotions

3. The Narratives of Hong Kong Kindergarten Teachers

4. The Resistance Movement: The Photovoice Approach

5. Method

- What were the emotional aspects of kindergarten teachers’ identities?

- How did the kindergarten teachers interpret their identities through their photo narratives?

6. Findings

6.1. Theme One: Role Modeling

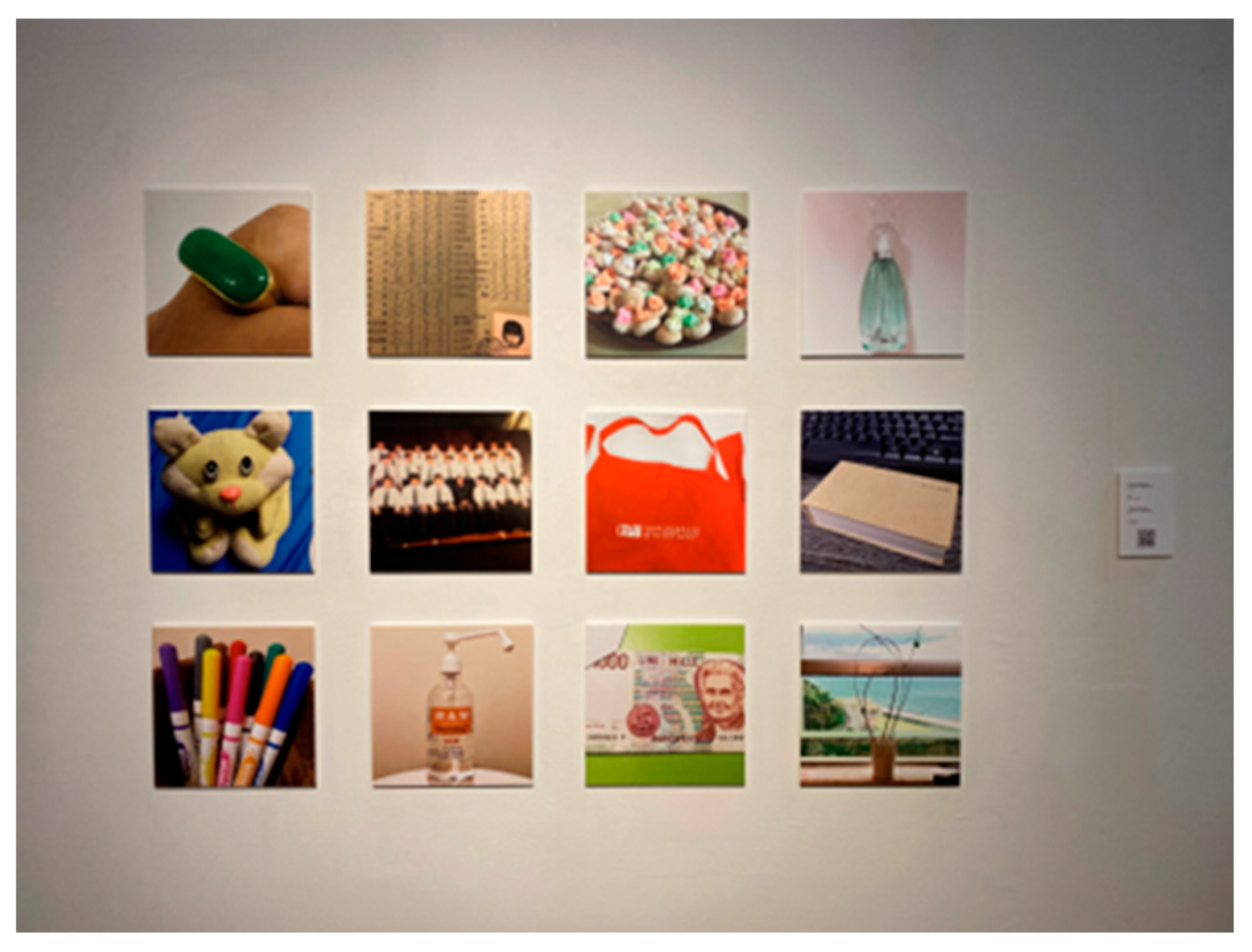

6.1.1. A Jade Ring (Teacher A; Male; Aged 32)

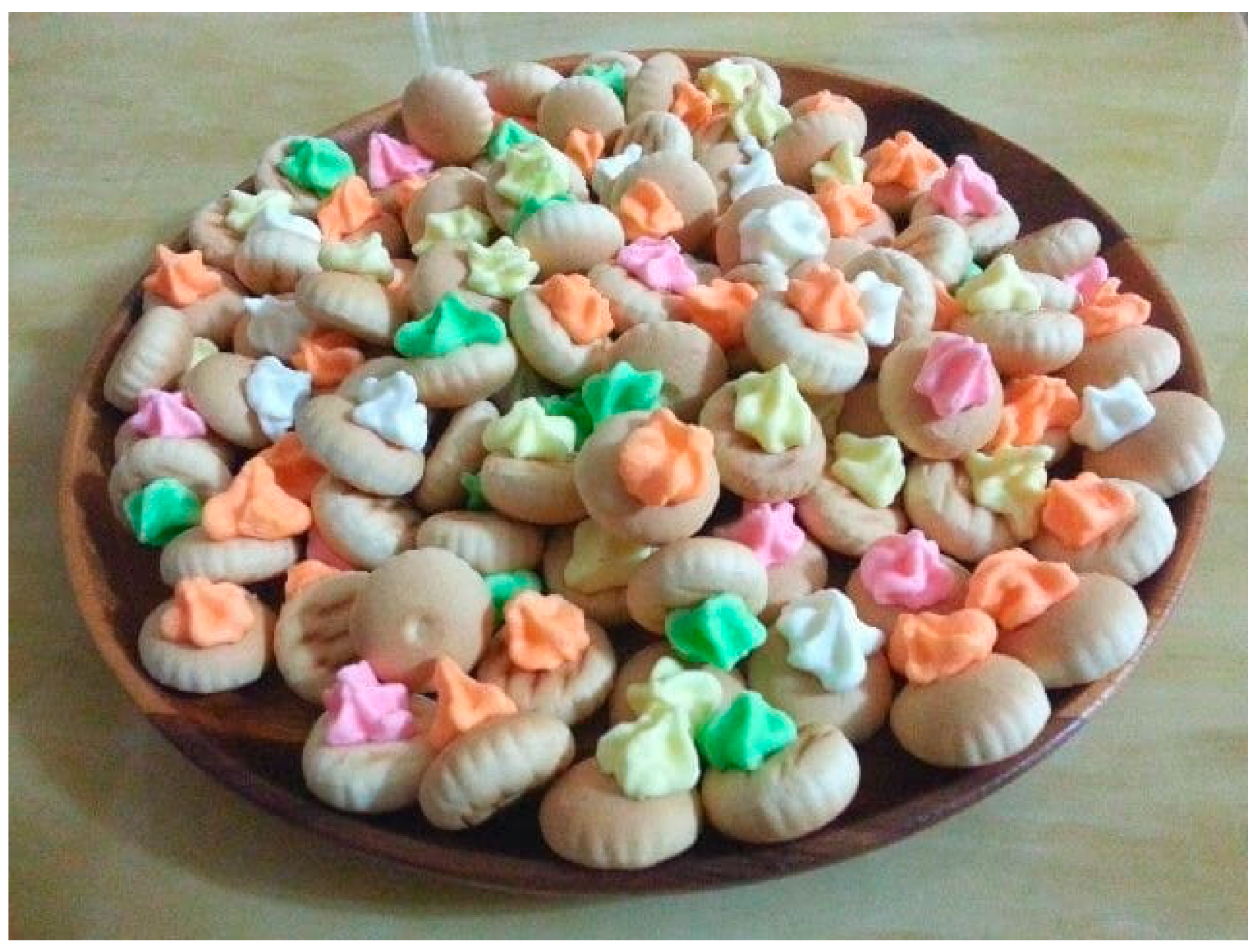

6.1.2. Meringue Cookies (Teacher B; Female; Aged 26)

6.1.3. A Bottle of Fragrance (Teacher C; Female; Aged 30)

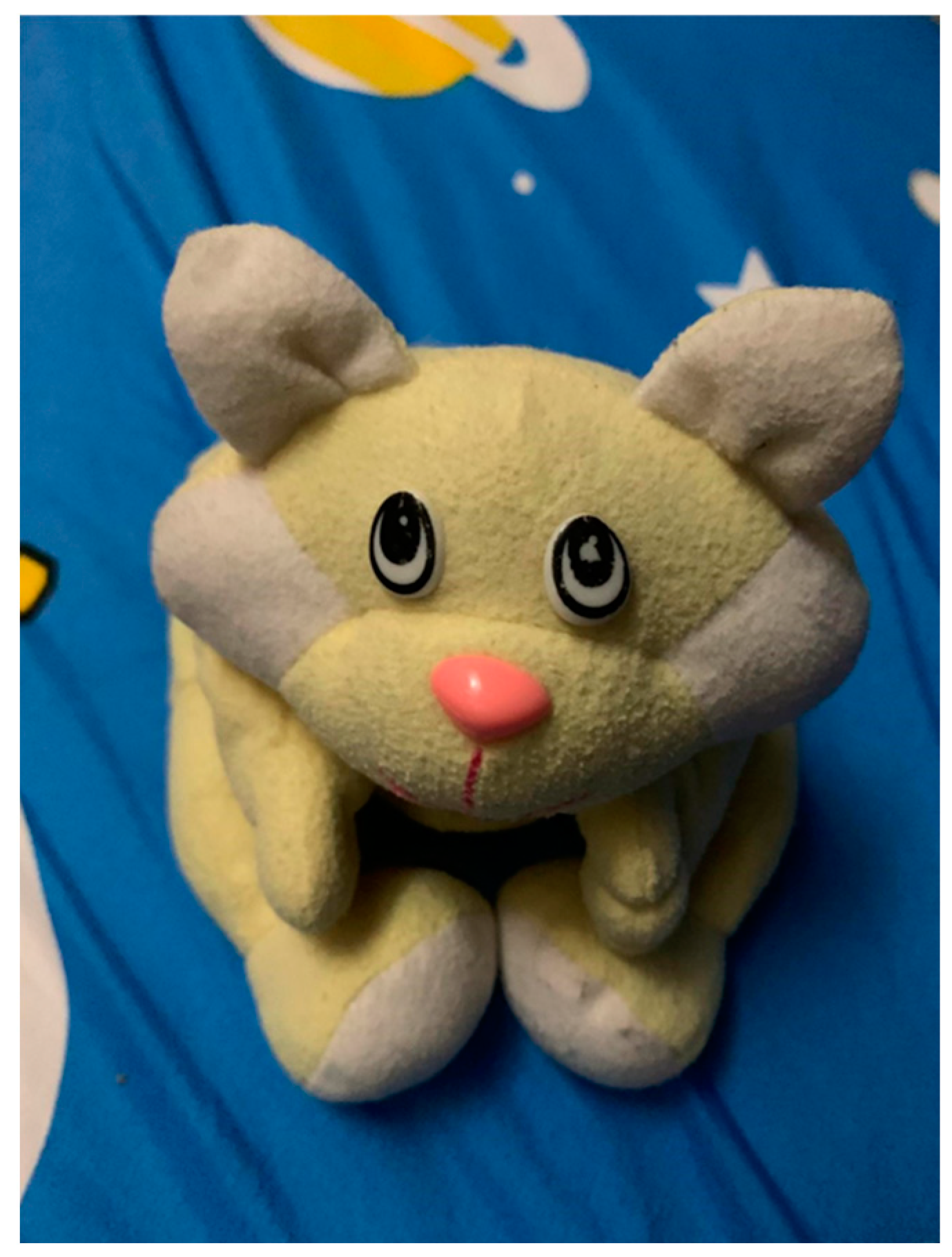

6.1.4. Bean (Teacher D; Female; Aged 24)

6.1.5. A Graduation Photo (Teacher E; Male; Aged 26)

6.2. Theme Two: Critical Reflection

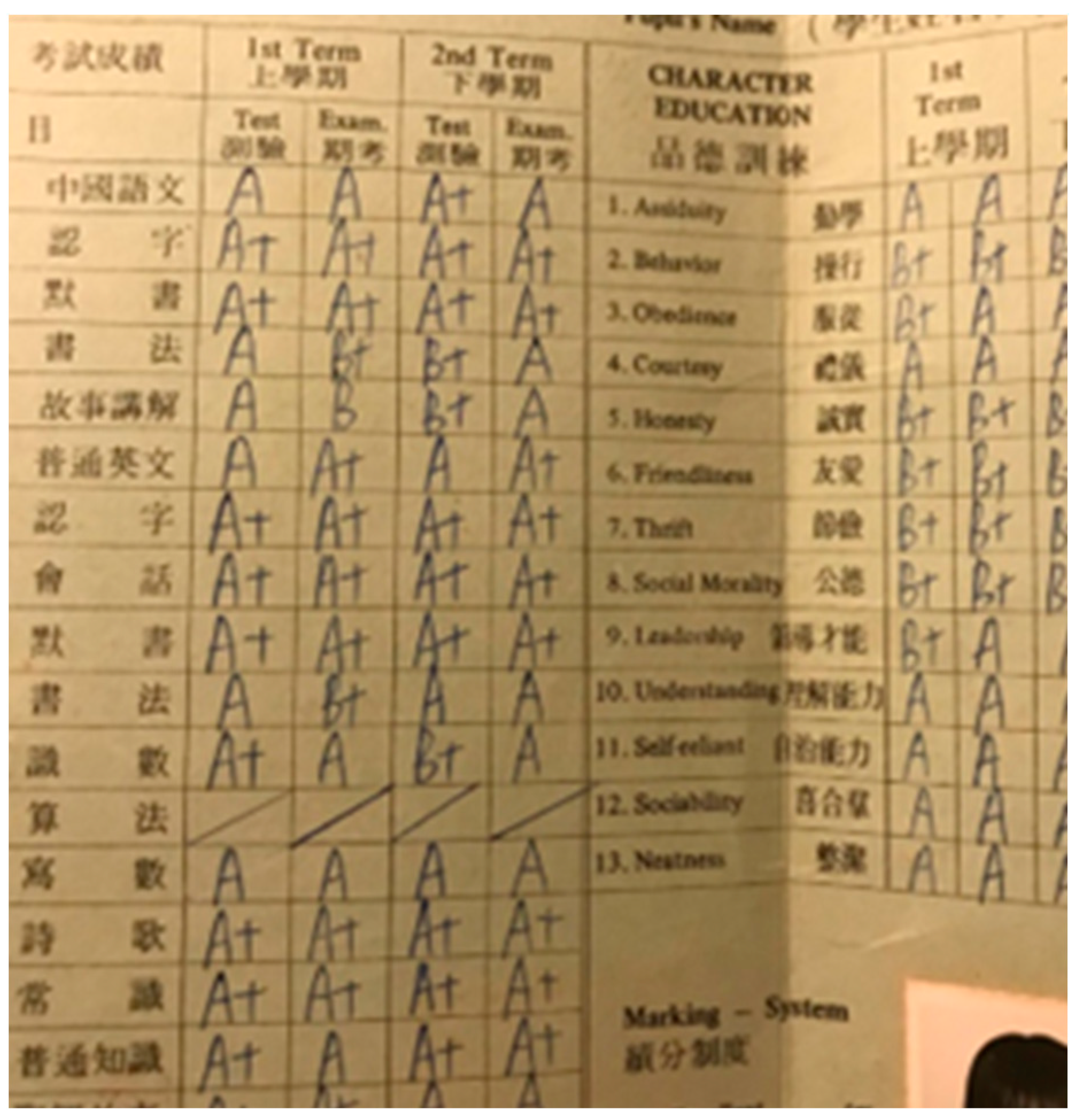

6.2.1. A Kindergarten Report (Teacher F; Female; Aged 39)

6.2.2. Washable Marker Pens (Teacher G; Female; Aged 27)

6.2.3. Hand Sanitizer (Teacher H; Female; Aged 32)

6.3. Theme Three: Personal Recognition

6.3.1. An Apron (Teacher I; Female; Aged 34)

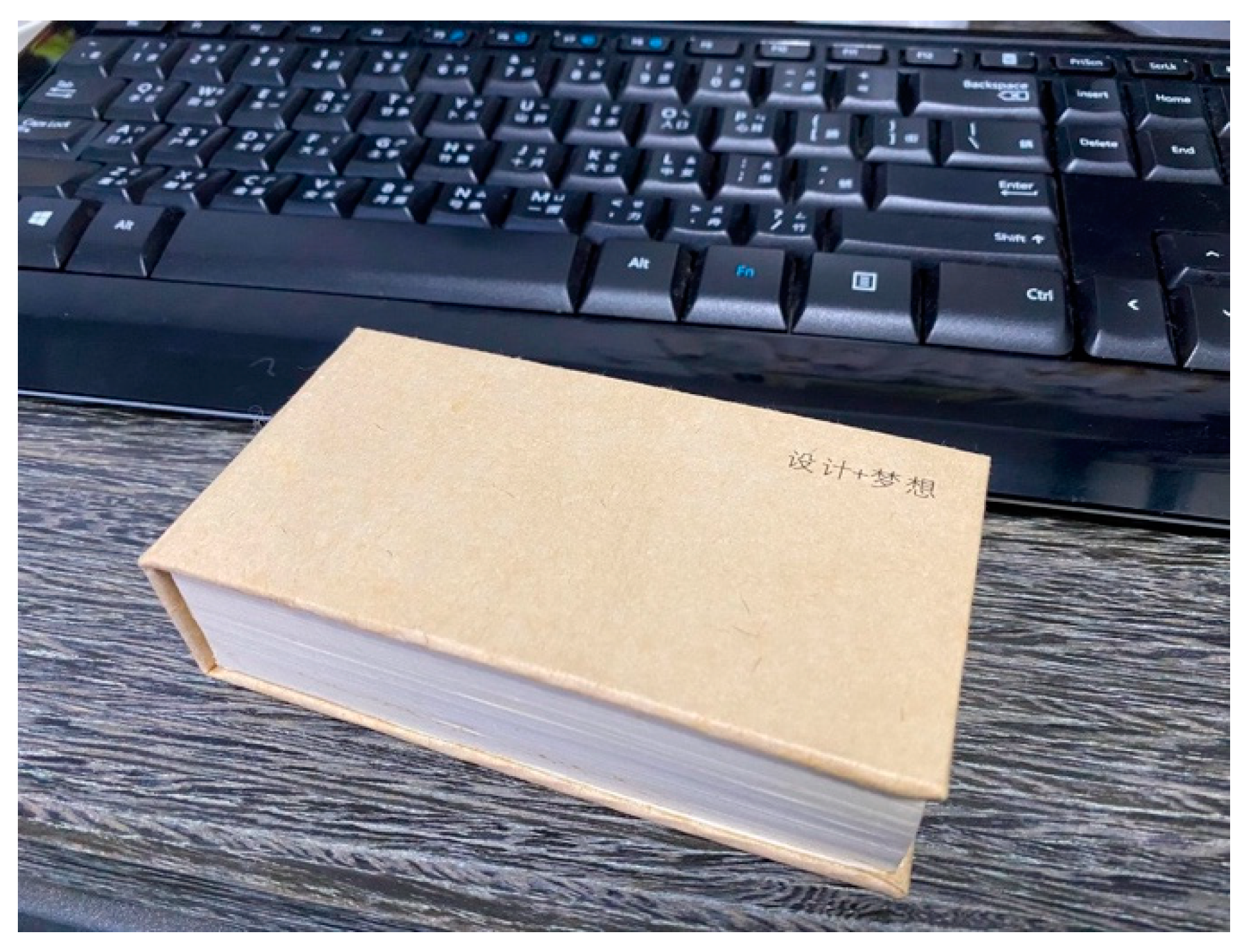

6.3.2. A Small Notebook (Teacher J; Female; Aged 42)

6.3.3. A Banknote of Maria Montessori (Teacher K; Female; Aged 51)

6.3.4. A Gift of a Plant (Teacher L; Female; Aged 33)

7. Discussion

7.1. Emotions in a Teacher’s Identity

7.2. Voices in a Professional Community

8. Conclusions

9. Declaration

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Researcher’s Diary (May 2020)

References

- Dahlberg, G.; Moss, P. Ethics and Politics in Early Childhood Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.S. Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics—Updated Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Lee, C.K.J. Be passionate, but be rational as well: Emotional rules for Chinese teachers’ work. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Beauchamp, C. Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb. J. Educ. 2009, 39, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, K.K. Teachers’ Work and Emotions: A Sociological Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, S.; Jiang, L. Chinese preschool teachers’ emotional labor and regulation strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 92, 103024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelchtermans, G. Who I am in how I teach is the message: Self-understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2009, 15, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Language Teacher Emotion in Relationships: A Multiple Case Study. Preparing Teachers for the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D.; Meijer, P.C.; Verloop, N. Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2004, 20, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. School reform and transitions in teacher professionalism and identity. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2002, 37, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, S.L.; Schutz, P.A.; Rodgers, K.; Bilica, K. Early career teachers’ emotion and emerging teacher identities. Teach. Teach. 2017, 23, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melucci, A. The Playing Self: Person and Meaning in the Planetary Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockler, N. Becoming and ‘Being’a Teacher: Understanding Teacher Professional Identity; Rethinking Educational Practice through Reflexive Inquiry; Essays in honour of Susan Groundwater-Smith; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Hadfield, M. Metaphors for movement: Accounts of professional development. In Changing Research and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Kington, A.; Stobart, G.; Sammons, P. The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. Brit. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 32, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. Professional identity matters: Agency, emotions, and resilience. In Research on Teacher Identity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. The emotional practice of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1998, 14, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Lei, X.; Huang, Z. Understanding a STEM teacher’s emotions and professional identities: A three-year longitudinal case study. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2021, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C. Teacher emotions. In International Handbook of Emotions in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 504–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, K.K. A review of current sociological research on teachers’ emotions: The way forward. Br. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.J.; Stets, J.E. Identity Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wojdyło, K.; Baumann, N.; Fischbach, L.; Engeser, S. Live to work or love to work: Work craving and work engagement. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Tam, W.W.Y.; Park, M.; Keung, C.P.C. Emotional labour matters for kindergarten teachers: An Examination of the antecedents and consequences. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2022, 32, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.; Antonela, M. Good Practice for Good Jobs in Early Childhood Education and Care; OECD: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/education/goodpractice-for-good-jobs-in-early (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Hong, X.-M.; Zhang, M.-Z. Early childhood teachers’ emotional labor: A cross-cultural qualitative study in China and Norway. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, J.J. Evolution of the early childhood curriculum in China: The impact of social and cultural factors on revolution and innovation. Early Child Dev. Care 2016, 187, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J.; Bruner, J.S. Acts of Meaning: Four Lectures on Mind and Culture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haremustin, R.T. Discourses in the Mirrored Room: A Postmodern Analysis of Therapy. Fam. Process 1994, 33, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts-Holmes, G.; Moss, P. Neoliberalism and Early Childhood Education: Markets, Imaginaries and Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, J.; Hatch, J.A. Teachers’ perceptions of integrated kindergarten programs in Hong Kong. Early Child Dev. Care 2007, 177, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, K.H.; Lam, C.C. The tension between parents’ informed choice and school transparency: Consumerism in the Hong Kong education voucher scheme. Int. J. Early Child. 2012, 44, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, L. Middle-class childhood and parenting culture in high-rise Hong Kong: On scheduled lives, the school trap and a new urban idyll. Child. Geogr. 2015, 13, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Lau, E.Y.H. Extracurricular participation and young children’s outcomes in Hong Kong: Maternal involvement as a moderator. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 88, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, K.W.-H. Learning, Teaching, and Researching in Shadow Education in Hong Kong: An Autobiographical Narrative Inquiry. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.W. Leading today’s kindergartens: Practices of strategic leadership in Hong Kong’s early childhood education. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, E. Kindergarten Education Schem. 2022. Available online: https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/edu-system/preprimary-kindergarten/free-quality-kg-edu/index.html (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Simpson, D. Being professional? Conceptualising early years professionalism in England. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, M.; Stevenson, W. The Impact of Teachers’ Advanced Degrees on Student Learning. In Human Capital in Boston Public Schools: Rethinking How to Attract, Develop and Retain Effective Teachers; Rivkin, S., Eric, G., Hanushek, E.A., Kain, J.F., Eds.; Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica; National Council on Teaching Quality: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 73, pp. 417–458. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED512671.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Rao, N.; Lau, C.; Chan, S. Responsive Policymaking and Implementation: From Equality to Equity. A Case Study of the Hong Kong Early Childhood Education and Care System; Teachers College: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.M. What Should the Left Propose? Verso: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The ethic of the care for the self as a practice of freedom: An interview with Michael Foucault on 20th January 1984. In The Final Foucault; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.J. Foucault, Power, and Education, 1st ed.; Routledge key ideas in education series; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C. Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching and Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Reading images: Multimodality, representation and new media. Inf. Des. J. 2004, 12, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Literat, I. “A pencil for your thoughts”: Participatory drawing as a visual research method with children and youth. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, F. Young People, Identity and the Media. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Westminster, London, UK, 2007. Available online: http://www.artlab.org.uk/fatimah-awan-phd.htm (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Gauntlett, D. Creative Explorations: New Approaches to Identities and Audiences; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gauntlett, D. Using creative visual research methods to understand media audiences. Medien. Z. Theor. Prax. Medien. 2004, 9, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattine-Flaherty, E.; Singhal, A. Method and marginalization: Revealing the feminist orientation of participatory communication research. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the NCA 93rd Annual Convention, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–18 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C. Photovoice: A Participatory Action Research Strategy Applied to Women’s Health. J. Women’s Health 1999, 8, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas. Implementing Photovoice in Your Community. 2020. Available online: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/photovoice/main (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Wass, R.; Anderson, V.; Rabello, R.; Golding, C.; Rangi, A.; Eteuati, E. Photovoice as a research method for higher education research. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 834–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.W.-Y.; Chu, C.K.-W.; Cheng, A.H.-H.; Hui, E.S.-Y.; Fung, K.C.-K.; Yu, H.H.-W. “Getting ready to teach”: Using photovoice within a collaborative action research project. J. Educ. Teach. 2021, 47, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, T.; Eisner, E.W. Arts Based Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, A.; Torre, M.E. Participatory Action Research in Education. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, M.E.; Fine, M. Participatory action research (PAR) by youth. Youth Act. Int. Encycl. 2006, 2, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. In Toward a Sociology of Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.B.; Christensen, L. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Q. Photographs and stories: Ethics, benefits and dilemmas of using participant photography with Black middle-class male youth. Qual. Res. 2012, 12, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G.; Pilotta, J.J. Naturalistic inquiry. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1985, 9, 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiff, J.; Whitehead, J. Action Research for Teachers: A Practical Guide; David Fulton Publishers: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.C. The critical incident technique. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 51, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. The 1000-page question. Qual. Inq. 1996, 2, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.A.; Wang, C.C. Photovoice: Use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience in older adults. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.; Moon, R. Introducing Metaphor; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijen, Ä.; Kullasepp, K.; Anspal, T. Pedagogies of developing teacher identity. In International Teacher Education: Promising Pedagogies (Part A); Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Negotiating psychological disturbance in pre-service teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2006, 22, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M. Student-teachers’ concerns about teaching practice. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2007, 30, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live by; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, H.-L.; Kwok, S.Y.; Hui, A.N.; Chan, D.K.-Y.; Leung, C.; Leung, J.; Lo, H.; Lai, S. The significance of emotional intelligence to students’ learning motivation and academic achievement: A study in Hong Kong with a Confucian heritage. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anspal, T.; Eisenschmidt, E.; Löfström, E. Finding myself as a teacher: Exploring the shaping of teacher identities through student teachers’ narratives. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2012, 18, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D.; Verloop, N.; Vermunt, J.D. Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: An exploratory study from a personal knowledge perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2000, 16, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijen, Ä.; Kullasepp, K. All roads lead to Rome: Developmental trajectories of student teachers’ professional and personal identity development. J. Constr. Psychol. 2013, 26, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D.J.; Connelly, F.M.; Bradley, J.G. Shaping a professional identity: Stories of educational practice. McGill J. Educ. Montr. 1999, 34, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, V. The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. Handb. Res. Teach. Educ. 1996, 2, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Volkmann, M.J.; Anderson, M.A. Creating professional identity: Dilemmas and metaphors of a first-year chemistry teacher. Sci. Educ. 1998, 82, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malderez, A.; Hobson, A.; Tracey, L.; Kerr, K. Becoming a student teacher: Core features of the experience. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2007, 30, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoštšuk, I.; Ugaste, A. The role of emotions in student teachers’ professional identity. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 35, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoštšuk, I.; Ugaste, A. Student teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.L.; Zhang, L.J. Teacher learning as identity change: The case of EFL teachers in the context of curriculum reform. TESOL Q. 2021, 55, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltodano, M. Neoliberalism and the demise of public education: The corporatization of schools of education. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2012, 25, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, M. Neoliberalism and early childhood. Cogent Educ. 2017, 4, 1365411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, M. Reconceptualising the child: Power and resistance within early childhood settings. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2014, 15, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teacher | Gender | Age | Education Level | Years of Teaching | Context/Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Male | 32 | Bachelor | 12 | Principal of a kindergarten |

| B | Female | 26 | High Diploma | 6 | Class teacher of a kindergarten |

| C | Female | 30 | High Diploma | 8 | Class teacher of a kindergarten |

| D | Female | 24 | Bachelor | 2 | Teacher of a special education center |

| E | Male | 26 | Bachelor | 4 | Class teacher of a kindergarten |

| F | Female | 39 | Master | 18 | Principal of a kindergarten |

| G | Female | 27 | Bachelor | 5 | Class teacher of a kindergarten |

| H | Female | 32 | Master | 10 | Deputy principal of a kindergarten |

| I | Female | 34 | Bachelor | 9 | Class teacher of a kindergarten |

| J | Female | 42 | Bachelor | 21 | Deputy principal of a kindergarten |

| K | Female | 51 | High Diploma | 27 | Deputy principal of a kindergarten |

| L | Female | 33 | Bachelor | 9 | Class teacher of a kindergarten |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, C.S.; Leung, S.K.Y.; Wan, S.W.-y. Unlocking Emotional Aspects of Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Identity through Photovoice. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040342

Pan CS, Leung SKY, Wan SW-y. Unlocking Emotional Aspects of Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Identity through Photovoice. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(4):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040342

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Chloe Simiao, Suzannie K. Y. Leung, and Sally Wai-yan Wan. 2023. "Unlocking Emotional Aspects of Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Identity through Photovoice" Education Sciences 13, no. 4: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040342

APA StylePan, C. S., Leung, S. K. Y., & Wan, S. W.-y. (2023). Unlocking Emotional Aspects of Kindergarten Teachers’ Professional Identity through Photovoice. Education Sciences, 13(4), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040342