1. Introduction

Studies on learning patterns and religious tolerance have yet to be carried out in a positivistic research paradigm [

1]. Attention is generally paid to learning material variables that contribute to an increase in tolerance [

2] but not to the area of student learning strategies and patterns. The current study generally used reporting, evaluating, comparing, or reflecting approaches to tolerance education policies such as the Messer student exchange program [

3] in Israel, Schweitzer’s [

4] interfaith education course in Germany, Kafatos [

5] theatre-based intervention in Greece, and RE Brockman’s [

6] comparison in Texas and Québec public schools. One recurring discussion in the study of religious tolerance is focused on affirming centrality and developing Allport’s contact hypothesis by optimizing interfaith contact to minimize prejudice and strengthen tolerance. The research has yielded important insights for promoting religious tolerance education in countries with a Christian majority. However, contemporary educational research has not explicitly reported on learning pattern variables’ effect on attitudes toward religious tolerance in Muslim-majority societies. This analysis is important because learning patterns’ appropriateness contributes significantly to behavior decisions [

7].

Contemporary research trends on religious tolerance have documented various case studies that point to specific educational programs [

8]. The studies employed discourse analysis to benefit research and promote tolerance in religious education (RE) settings, specifically in alternative areas for conducting discursive exploration in developing tolerance education policies. Whereas in Southeast Asia, previous research has found empirical benefits through contemporary case studies of Indonesia, where religious conservatism and intolerance tend to experience an increase [

9]. This article begins by briefly reviewing previous studies and highlighting the gaps that need more study on the influence of learning patterns in forming a tolerant attitude. Therefore, this article highlights the phenomenon and potential for intolerant actions in a pluralistic Indonesian context, followed by a theoretical study of the role of learning patterns in countering intolerance. Finally, a quantitative measurement was carried out to see the magnitude of the influence of learning patterns on students’ tolerant behavior.

Apart from the two studies above, the primary publication from the Indonesian context related to this article is the work of Marintan [

10] on the effect of democratic parenting on tolerance. By accurately identifying that democratic parenting is not enough without theological transformation from exclusive to multiculturalist, Marintan proposed that democratic parenting must be built in tandem with Indonesian Islamic traditions closely linked to religious dogmas. He crystallized his theology into four core, ten implementation-level, and three level values. Such as the proposed concept of God’s mercy in Islam, which encourages humans to give attention to each other and spread love, even with different religious beliefs. Another concept used by Marintan is mutual respect between religious communities. It does not matter what religion you follow; people must respect one another. Vermunt, JD, and Donche [

11] considered Marintan research as the first role in developing tolerance, multicultural education, and relevant to the Indonesian context.’ This article takes Marintan’s work further by analyzing of learning patterns as a discursive embodiment of the curriculum influence the behavior of religious tolerance.

2. Views of Different Religions on the Phenomenon of Intolerance in Indonesia

Indonesia is a multicultural country that has 1340 ethnic groups, 6 recognized religions, and 5 races, which sometimes provokes intolerance [

12], evidenced by rampant acts of intolerance, especially after the fall of the New Order regime. Intolerance can be observed even more so in conflict-prone areas, along with opening channels of identity politics that carry the name of religion [

13]. At least three sad incidents have been recorded due to society’s inability to promote tolerance for a diversity of identities. For example, the Islamic–Christian conflict in Ambon and Maluku, which caused the loss of hundreds of lives; the (Islamic–Christian) religious conflict in Poso, which resulted in the deaths of 577 residents, 384 injuries, and 7932 destroyed houses; and the Sampit–Madura conflict, which resulted in the killing of 315 residents [

14]. Other acts of intolerance also occurred in conflict-prone areas, for example: the Cikeusik conflict in Banten and wars between villages and customary lands in Papua or West Nusa Tenggara. Trijono’s analysis states that this series of events started due to the incompatibility of implementing religious norms and cultural interests due to social change in a heterogeneous society [

15]. Facing this phenomenon, tertiary institutions must provide a learning model of religious tolerance by using student learning patterns to achieve learning objectives.

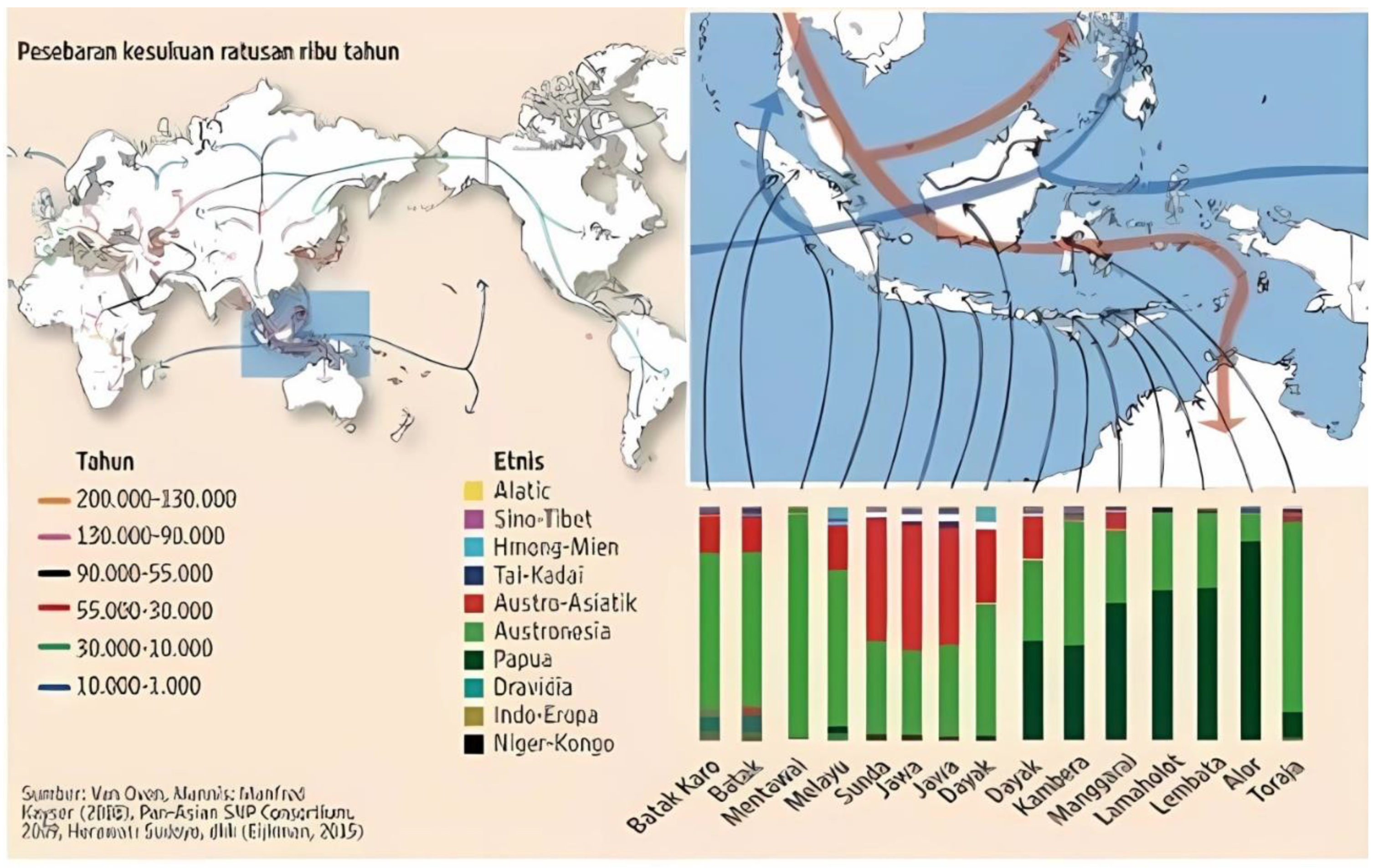

Figure 1 shows the Indonesian human genetic map.

Respect and tolerance for practitioners of other faiths are essential components of diversity in Islam. The Indonesian Ulema Council, initiated by Islamic figures, issued a fatwa on religious pluralism that supports tolerance in 2005.

“An understanding that teaches that all religions are the same and therefore the truth of each religion is relative. Therefore, every religious believer may not claim that only his/her religion is right while other religions are wrong. Pluralism also teaches that all religious adherents will enter and live side by side in heaven [

16].”

Pluralism is viewed as part of Islam’s essential attitude, namely being open to dialogue and accepting differences fairly. People are expected to have an ethos of reading, nurturing, learning, and being smart through openness and a dialogical attitude [

17]. Unfortunately, the community and religious leaders do not sufficiently understand this view. Some even think that pluralism is an attitude or idea that believes in the truth of all religions.

In the opinion of Indonesian Christians, John Hick [

4] has shaped the understanding of religious tolerance in the preceding decades. Hick says religious tolerance is closely related to pluralism as a particular theory regarding the relationship between traditions and various claims. This term implies that the world’s major religions significantly shape multiple perceptions regarding religious tolerance [

3]. In line with this, Indonesian Buddhists follow the example of the Buddha on religious tolerance. For example, King Asoka made a decree on a mountain rock, which read,

“One should not honour only one’s religion and condemn the religions of others. However, one should honour others’ religions for this or that reason. So doing, one helps one’s religion to grow and renders service to the religions of others too” [

3]. In acting otherwise, one digs the grave of one’s religion and harms other religions. Whoever honours his religion and condemns other religions does so indeed through devotion to his religion, thinking, “

I will glorify my religion. However, on the contrary, in so doing, he injures his religion more gravely” [

18].

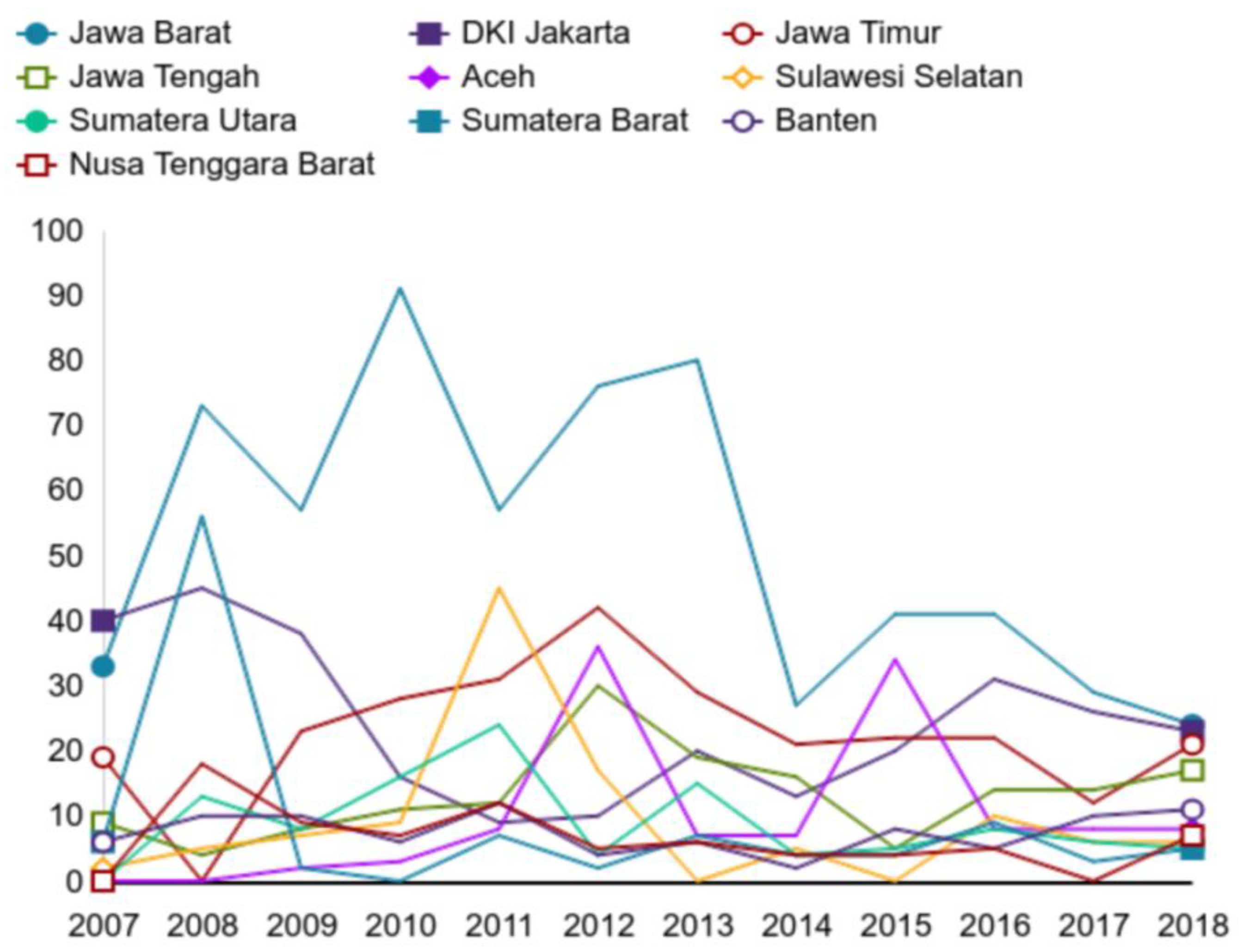

Meanwhile, the Setara Institute noted that from 2007 to 2018, there were 2400 violations of the Conditions of Freedom/Belief (KKB), with the most cases occurring in West Java, with most victims belonging to the Ahmadiyah congregation [

19].

Figure 2 shows the level of religious tolerance in several provinces in Indonesia.

Contrary to the data above, recent developments on the issue of religious tolerance in Indonesia show a positive trend. The Vice President of Indonesia, for example, Ma’ruf Amin, said that Indonesia received good recognition from various nations because of its inter-religious harmony: “They see how we can build the nation’s integrity because there is an agreement with Pancasila. So, they are amazed” [

20]. He said that sometimes Indonesia needs to be aware that it has become the spotlight for other countries regarding religious tolerance. Amin also shared his experience of being visited by a team of film producers from Italy who wanted to document inter-religious harmony in Indonesia, including in Borobudur Temple in Central Java, Mount Bromo in East Java, and the interior areas of Lebak, Banten [

21]. This shows Indonesia’s acceptance in the eyes of the world as a tolerant society in the area of religion.

3. Theoretical Review

Within the theoretical framework of learning patterns, research has consistently identified three qualitative ways related to how students learn: learning directed (cognitive patterns), learning required (socio-affective patterns), and practical-empirical patterns [

11,

22]. In learning directed (cognitive patterns), students attempt to recall the learning material in order to attain a high exam score. They remember the material and study it sequentially and step-by-step, without considering the link between bigger pieces [

23]. They adhere closely to the guidelines established by teachers, study materials, and other external actors. The purpose of their learning is to pass tests or assess their abilities. They consider learning as essentially the acquisition of information from other sources for one’s own use, imitating every material given by the lecturer in the same way. This pattern is determined by a stepwise procedure with the ILS scale (consisting of the ‘memorize and practice’ and ‘analyze’ subscales), external regulation, knowledge intake as a theory of learning, as well as directed certification and directed learning orientation [

22].

Students who study with socio-affective patterns adopt a deep learning approach. Their understanding focuses on what they learn, arrange some facts from the separation of the view, and criticize the learning material he developed [

24], and engage with what they are learning. They have a unique way of learning, do not want to be locked up in the material determined by the lecturer. Student perspectives uphold the construction of knowledge as personal responsibility [

25]. Student encouragement is deeper about the topic of study that is processing on the ILS scale with the subscala connect and compose and the criticism process.

Finally, students who learn using practical-empirical patterns seek connections between knowledge gained in class and outside the classroom, such as what to learn, and consider the application of the method to study practice [

26]. They are more interested in learning material that he thinks is useful for life today, knowledge that is not related to that they consider it not important [

24]. Their tendency to the work side to have good performance and ability.

The learning pattern trend is based on a quantitative research view, meaning that latent factors can be distinguished based on factor analysis, which reflects coherent patterns and correlates between differentiating scales. The pattern of learning shown must be understood as a framework that is sometimes noticed or not noticed. Some people exhibit all of the characteristic learning patterns; others are more flexible and show characteristics of one, two, or even three patterns. This causes a combination of different learning patterns to occur in small groups in the class [

11].

Figure 3 describes the model of learning patterns adopted by students. Cognitive strategies affect students’ conceptions and motivation in learning, play a role in processing learning materials. This orientation leads to learning outcomes that are influenced by various contextual and personal factors. Their understanding plays a role in providing capital for further learning. Even changing learning contexts can also change the patterns experienced before [

11]. All lines between elements are drawn as links to emphasize the dynamics of the model. Individual characteristics regarding intelligence beliefs also influence the way students learn.

Figure 3 Shows the types of learning patterns and influencing factors.

Not an unchangeable human characteristic, learning patterns are the result of the interaction between personal and contextual influences [

12,

13]. In previous research, the coordination of these concepts is commonly referred to as ‘learning patterns’. However, Even so, there is still an assumption that learning patterns are human nature that cannot be changed [

11,

27]. Because of this, research trends since 2004 no longer call it a ‘learning pattern’. Instead, researchers are better suited to understand the concept of learning patterns as dynamic terms that represent a whole set of student learning strategies, perspectives, and motives [

28].

Multiple personal and contextual factors impact students’ learning patterns, according to previous studies. Some of the things that influence are age, subject matter knowledge, and educational history. Important contextual aspects that influence student learning include the instructional techniques used, the kind of evaluation, and opportunities for student collaboration [

29]. The student’s learning process is also proven to be associated with student learning outcomes. For example, several studies have shown that student learning outcomes are often associated with meaningful learning patterns, for example student activities related to composing, critical engagement, and analytical procedures that may be experienced [

30].

Hawk, TF and Shah, Clark, and Janine, revealed that learning patterns could influence students’ ability to accept diversity [

31]. Learning patterns as a series of learning become sustainable habits that lead to behavioral tendencies [

32]. However, unfortunately, learning patterns need to be remembered in the literature study of religious tolerance [

3]. Contemporary discussion of tolerance has tended toward two less-related domains. First, existing studies only discuss the theoretical literature presented by Wegner [

33] and Alam, Mansur [

34]. Second, research on tolerance is associated with anti-radical character learning and its influence on understanding societal ideology [

28].

Meanwhile, research in learning patterns tends to look at the effect of learning attitudes on the selection of learning media [

35]. Alternatively, one could relate it to the learning patterns used by students. Compared to previous research, this research seems to be one step ahead. We tried to see the influence of cognitive, socio-affective, and practical empirical learning patterns on tolerant behavior in knowledge, affection, or actions [

36]. This variable was chosen to measure the extent to which the success of Islamic learning can instill religious tolerance. Furthermore, this research is expected to identify what learning patterns can improve understanding, affection, and actions of religious tolerance as attitude variables (See

Table 1) [

13].

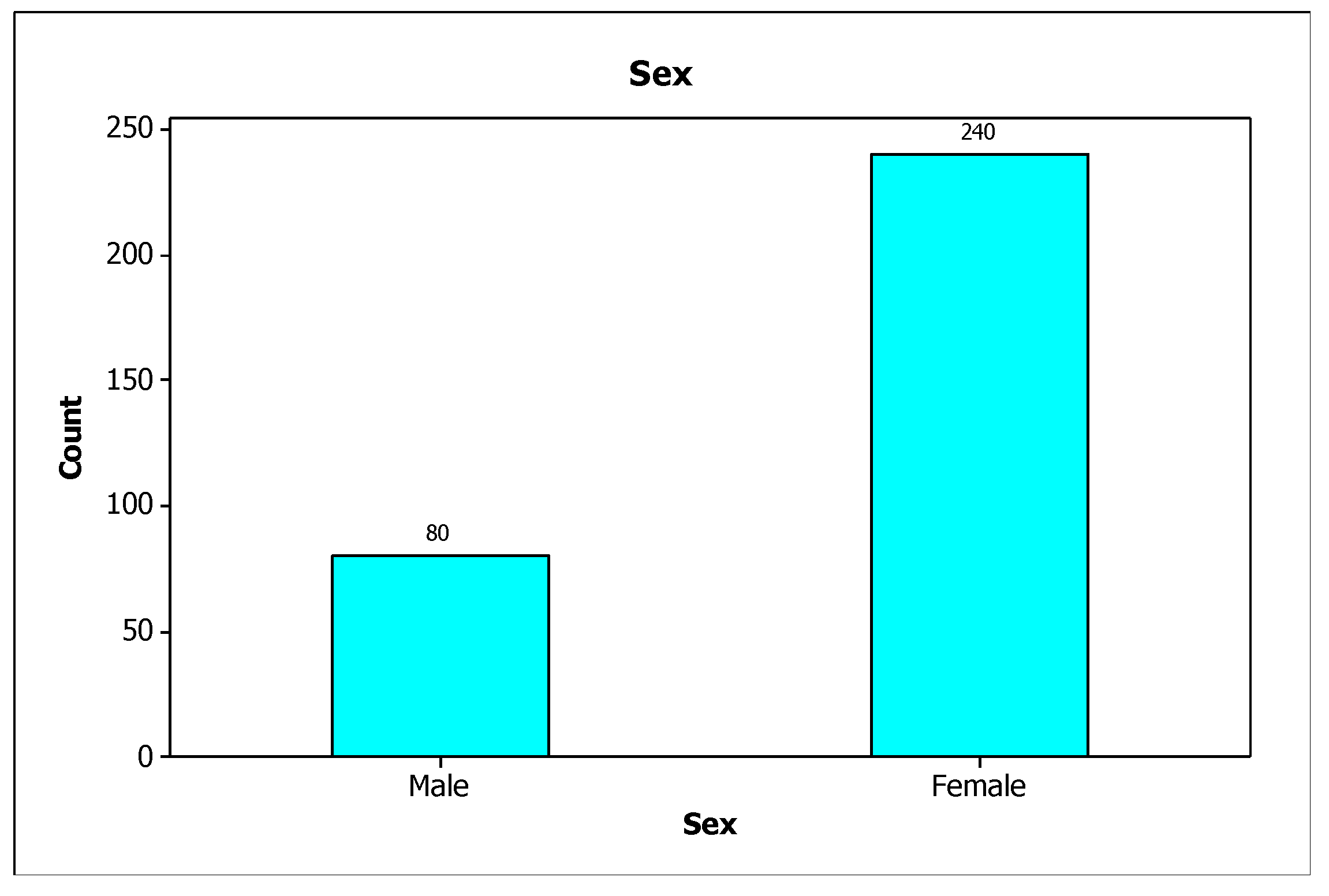

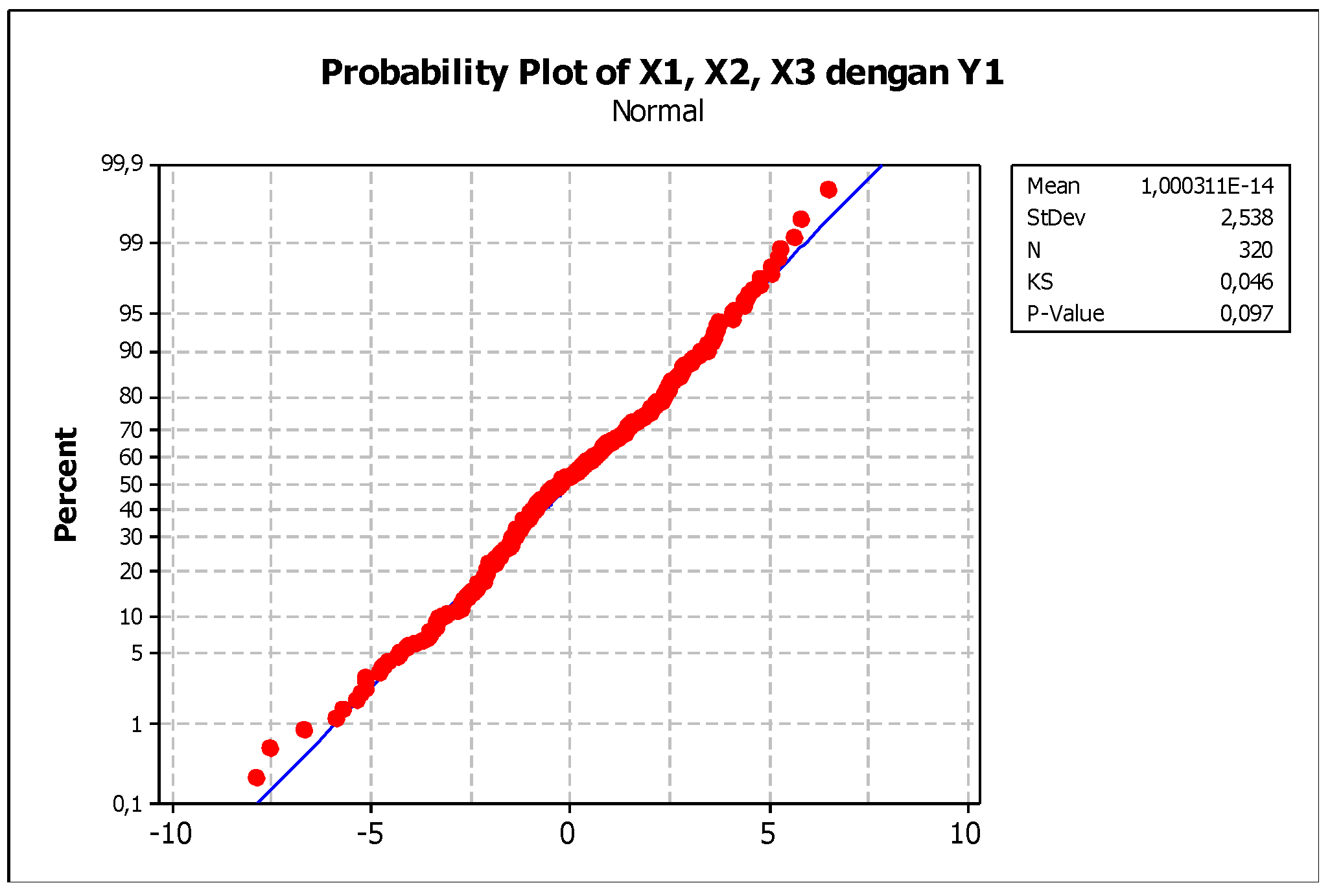

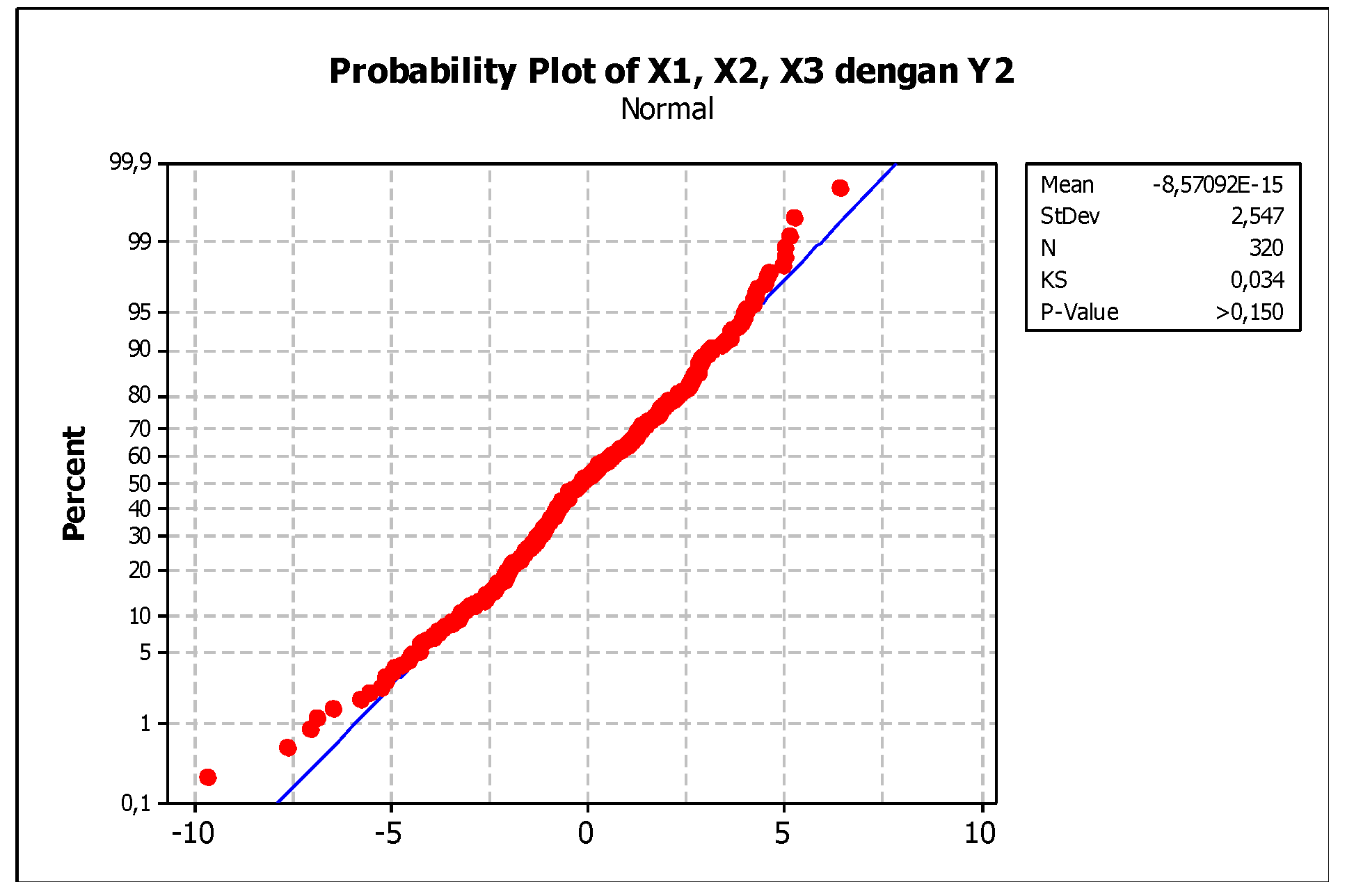

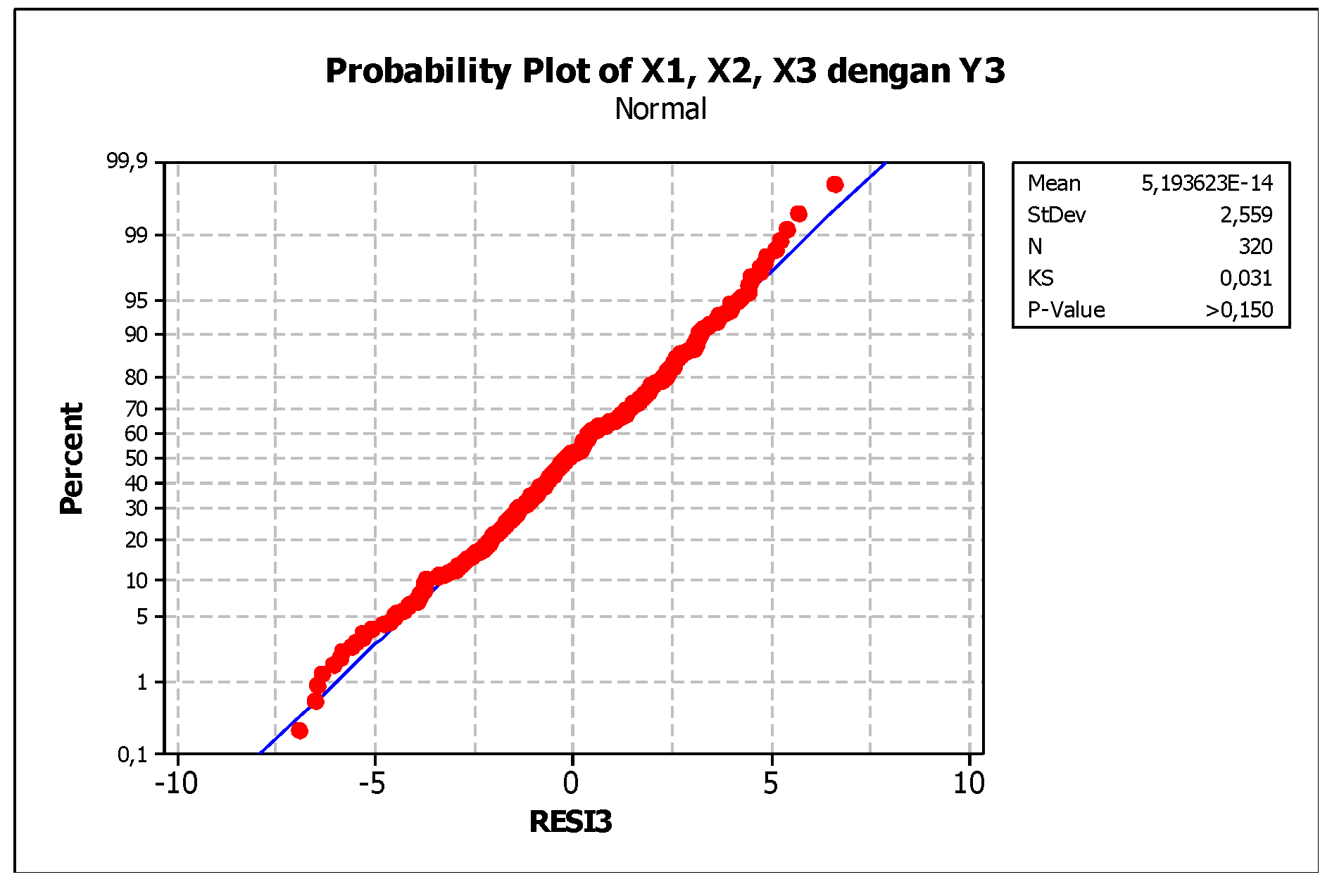

X and Y research variables are then broken down into sixty questions where X1 is a Cognitive pattern, X2 is a Socio-Affective pattern, and X3 is an empirical practice. Y1 is knowledge of religious tolerance, Y2 is a feeling of religious tolerance, and Y3 is an actual act of religious tolerance.

A simultaneous test is used to see the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable. The accompanying test hypothesis can be written as follows:

meaning that the independent variable has no significant impact on the dependent variable,

there is at least one .

Test Statistics:

The following are the test statistics used in the form of an ANOVA table (See

Table 2).

Critical area:

Reject if means that at least one independent variable has a significant effect on the dependent variable.

Partial Test Hypothesis:

independent variable has no significant effect on the dependent variable).

(the independent variable has a considerable impact on the dependent variable).

Test Statistics:

where,

Critical Areas: Reject H

0 if,

6. Discussion

The analysis results of the simultaneous test (F-test) show that the three learning patterns significantly influence religious tolerance. The data can be seen from the p-value (0.00) < alpha (0.05 and F > F-table). This study shows that: First, the level of student knowledge about religious tolerance is dominantly influenced by cognitive learning patterns with values (p-Value (0.00) < alpha (0.05)) and t values (10.21) > t table (1.97). The socio-affective score is (p-Value (0.021) < alpha (0.05)) and t value (2.32) > t table (1.97). In contrast, practical-empirical learning patterns show the most minor influence with a value (p-Value (0.045) < alpha (0.05)) and t (2.01) > t-table (1.97). Second, awareness of affection of religious tolerance is more dominantly influenced by cognitive and socio-affective learning patterns. The respective values are (p-Value (0.00) < alpha (0.05)); (t (9.50) > t table (1.97)); and (p-Value (0.00) < alpha (0.05)); (t (3.65) > t table (1.97)). Of course, this figure is better than the empirical-practical learning pattern, which only has a p-Value of 0.043 (p-Value (0.43) < alpha (0.05)); (t (2.03) > t table (1.97)). Third, towards tolerant actions, cognitive, socio-affective, practical-empirical learning patterns have the same effect, namely (p-Value (0.00) < alpha (0.05)).

The research findings indicate that three trends link cognitive learning and socio-affective patterns with religious tolerance. First, the cognitive learning pattern influences students’ understanding of religious tolerance, with a p-Value reaching 0.00, followed by a socio-affective pattern with a p-Value of 0.021. In contrast, practical-empirical learning patterns show the most minor effect, with a p-Value reaching 0.045.

These results are in line with the literature study by Saputri et al., which stated that cognitive learning patterns encourage students to improve their thinking skills [

23]. The patterns drive the brain-based abilities needed to perform any task, from the simple to the most complex [

40]. Furthermore, research conducted by Kusumaningtias (2013) would support the results of this study. He explained that someone with a cognitive learning strategy that is too dominant sometimes overrides practice and feeling; he only stops acting on the thinking side but does not carry out or feel what he is thinking [

41].

In the second result, this study shows that all X variables fully influence affection of tolerance. The magnitude of the influence of the cognitive learning and socio-empirical learning patterns has a p-Value of 0.00. In other words, these two understanding patterns contribute to determining students’ affection for tolerance. Of course, this figure is better than the empirical-practical learning pattern, which only has a p-Value of 0.043 in its effect on forming affection of tolerance. So, the meaning of this data shows that cognitive learning and socio-empirical learning patterns greatly influence affection of tolerance. However, practical-empirical learning patterns also have an influence, although it is small.

Of course, this second set of data is in line with the expression of Waters [

42], which states that thoughts and social conditions influence affection. Cognitive learning patterns emphasize the ability to remember and think logically [

43] and understand causal concepts rationally and systematically [

44]. Meanwhile, socio-affective learning patterns tend to emphasize emotions, such as appreciation, values, affection, enthusiasm, interests, and attitudes toward things [

45]. The correlation between the two is at the level of feeling, where the feeling is a form of order traveling from the mind’s work [

46] so that the balance between cognitive and socio-affective learning patterns becomes a unique combination to create affection of tolerance.

Somewhat differently, the results of this second study contradict the conclusions of Timothy Plex’s research, which state that a person’s affection is a form of spontaneous action without thinking. Also, contrary to what Suzi Jagger explained, the socio-affective treatment is a subjective treatment that overrides thinking [

47]. This research confirms that cognitive learning patterns that prioritize reason and socio-affective ones that emphasize affection have the same significant influence in shaping students’ affection of tolerance. This finding certainly supports Fadli and Ulil’s research, in line with the research described in the previous paragraph, that affection for tolerance is also influenced by a person’s knowledge of the phenomenon of religious tolerance [

48].

In the third trend, this study shows that tolerant behavior is significantly influenced by all learning patterns studied in the research. Cognitive learning patterns have a

p-Value of 0.00, and socio-affective and practical-empirical learning patterns have a

p-Value of 0.00. These data indicate that in this research, cognitive learning patterns, socio-affective learning patterns, and empirical-practical learning patterns have the same influence in encouraging students to display tolerant actions. This may be in line with Jensen’s research, which states that attitude is a conclusion from behavior [

49]; in other words, a person’s behavior is a form of embodiment of what he thinks and feels.

However, the data from the third research are at odds with the study mentioned by Utami, which explains that action is only based on habits or traditions that already exist in the surrounding environment, not thoughts [

50]. Alternatively, Widiyati’s analysis explains that actual action is determined by the emotional state of the perpetrator [

51]. Of course, this is nothing new because both of these studies received criticism from Mutiar et al., who explained that actions are carried out based on the actor’s specific goals. He strives to achieve his goals himself. In other words, value rationality has a role in determining personal action choices.

Overall, the data from this study indicate that the cognitive learning pattern has a more significant influence on the formation of tolerant thinking, besides being influenced by the other two learning patterns, even though in a small percentage. Whereas in the realm of affection, research shows that cognitive and socio-affective learning patterns have an equally dominant influence compared to empirical-practical learning patterns. Meanwhile, in the realm of tolerant behavior, this study shows that cognitive, socio-affective, and practical-empirical learning patterns have the same influence in shaping students’ tolerant attitudes.