Student and Language Teacher Perceptions of Using a WeChat-Based MALL Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic at a Chinese University

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Aim and Questions

- (1)

- What were Chinese university students’ and language teachers’ opinions of using the self-developed WALL program for university English vocabulary learning and teaching during the pandemic?

- (2)

- What were Chinese university students’ and language teachers’ evaluations of the WALL program?

4. Research Methods

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Participants and Sampling Techniques

4.3. Research Instruments

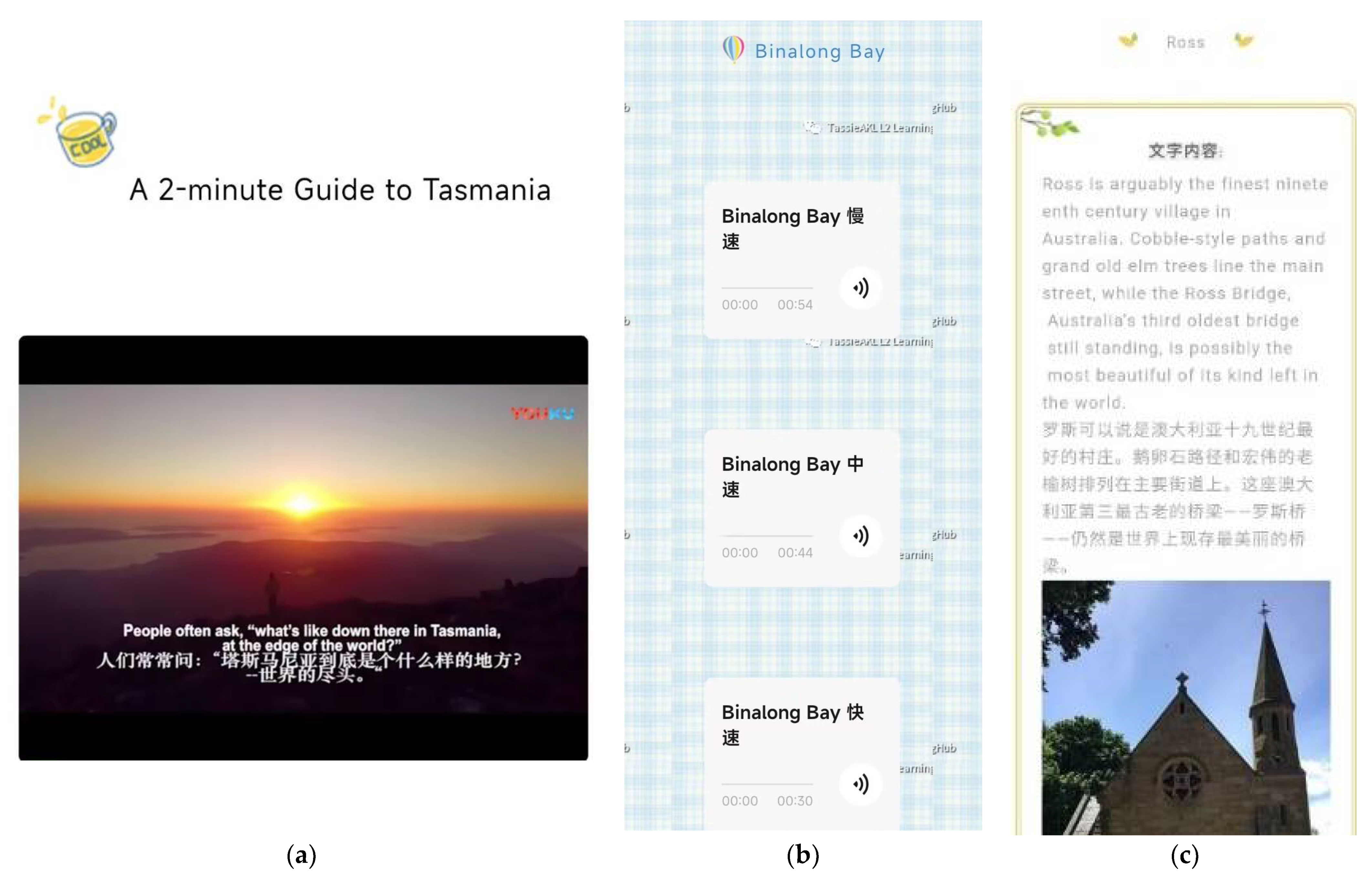

4.3.1. The WeChat-Assisted Language Learning Program (the WALL Program)

4.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

5. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Theme 1: Students’ and Language Teachers’ Evaluations of the WALL Program

6.1.1. Program Design

The research team made the right decision because we use WeChat and public accounts every day. They are a part of my life. So, it’s natural to use WeChat, even for learning purposes. (Student No. 4)

WeChat and public accounts empower us with instant messaging, including voice and video calls, with lovely widgets and GIFs. Also, public accounts provide us with information in different forms, like texts, graphics, audio, and videos. (Student No. 2)

The topics in the bonus resources were entertaining to read. They were about different aspects of the introduced place, such as traffic rules. These greatly raised my motivation in reading the posts because I had rarely heard about or known these things before. I was attracted to find out more about the topics and to use the program in the long term. (Student No. 3)

I saw most students were fascinated by the topics. They were able to know about a particular location overseas, ranging from its local cultures, social life, and natural scenery. As the teacher, I was also intrigued by these contents because I felt curious about the contents. (Lecturer No. 3)

6.1.2. Delivered Learning Resources

The audio materials were an effective tool for the students with different language-proficiency levels because they were able to select the speeds that suited them the best, namely slow, medium, and fast. For me, I often selected the slow speed for intensive vocabulary learning, writing down each word as I could. I practiced my listening skills using the medium speed. The fast speed helped me improve my speaking and fluency. These three speeds were used differently for personalised learning purposes. (Student No. 5)

The audio-formatted resources helped the students learn vocabulary and benefited their different language skills, such as listening and speaking. They were able to read after the audio or scripts. It was also like a level-up game that motivated the students in achieving the learning tasks due to the different speeds. They could move up to the next level, which was more challenging, after they had managed the current difficulty level. (Lecturer No. 1)

The videos improved my different language skills, such as listening, speaking, and translating. This was because videos combined textual, audio, and visual information together for vocabulary learning. Also, lexical knowledge became more vivid than the content presented in plain texts in my textbooks. Sometimes, the videos were a good way of entertainment after study. (Student No. 1)

Memorising new words in the conventional way, such as rote learning, copying wordlists, and doing dictations, remains a pervasive approach for vocabulary learning in most Chinese universities. I believe there are some teachers and students who still prefer text-formatted materials. As well, remembering the word form was the most direct and regular approach for the students to learn vocabulary. It was particularly true for non-English major students, like those recruited in this research project. (Lecturer No. 2)

6.1.3. Designed Learning Activities

The daily practice successfully enhanced my vocabulary-learning outcomes. Because doing follow-up practice helped me have a deeper impression of and a better memory of the lexical knowledge and items I learned. Also, the daily practice pushed me to review the lexical items every day after learning the delivered learning content. (Student No. 3)

The daily practice, as spaced repetitions of the target lexical knowledge, strengthened lexical-learning effects through frequent reviewing of the learning materials. As well, the students were able to examine their learning achievements or performances. (Lecturer No. 1)

6.2. Theme 2: Advantages of WeChat-Based Learning Approaches

6.2.1. Learner Friendliness

WeChat-based learning approaches made vocabulary learning easy for me. Because learning was more convenient, compared to the traditional methods I used to apply, such as reciting target lexical items in my English textbook. I mean, I didn’t have to bring learning materials to learn vocabulary. All I needed was WeChat on my mobile phone. (Student No. 4)

I was able to learn vocabulary anytime and anywhere. For example, when I was on the go, such as heading to classrooms or for the next classes, I was able to listen to the audio materials. Also, when I was on the shuttle bus to the apartment and lining up in the cafeteria, I was able to see the short videos on the program. I didn’t need to sit in the classroom or library to learn. More importantly, I was able to take notes using my phone. (Student No. 5)

6.2.2. Motivation Enhancement

Most students in my class tended to have a stronger interest in learning the target lexical items delivered on the program. For instance, some watched the videos before classes and during class breaks. Some discussed the content they had problems with partners and in groups. Also, some students asked me for help. They were fascinated with the learning content and topics and would like to learn more about the target vocabulary actively, compared to their old learning behaviours. (Lecturer No. 3)

Most students showed stronger learning motivation because they found WeChat-based learning approaches interesting to use. They engaged in learning the target lexical items and using the WeChat-based program because of the sense of novelty. As a language teacher, I found it fun to use WeChat for vocabulary teaching myself, as well. (Lecturer No. 2)

6.2.3. Support for Collaborative Learning

WeChat-based learning approaches supported my vocabulary learning with my fellows. I often learned the target lexical items delivered by the program with my best friends or roommates. As well, we quizzed each other on some important lexical content. Additionally, if I had some problems with the delivered lexical-learning content, I was able to leave messages to or have instant communication with the straight—A students in my class. If they couldn’t figure out the answers, I would turn to my teacher for learning assistance and guidance on WeChat. (Student No. 3)

We recited the target lexical items together after class. We also did the vocabulary quizzes on the program in groups to check how well we had learned. We often quizzed each other. WeChat provided instant communication and prompt learning assistance. We were able to get help from our fellow students and teachers. (Student No. 1)

6.3. Theme 3: Problems of the WALL Program

6.3.1. Distracting Learning Environments

It was hard to stay focused due to the inevitable distractions. I mean, there were unexpected messages on WeChat when I was learning vocabulary or watching the videos using the program. There was not much I could do about it, since WeChat is a social app. (Student No. 4)

It was hard to focus on learning vocabulary using the program because of the disturbances on WeChat and mobile phones. Unlike in classrooms where teachers are always around, I found it challenging to ensure my learning efficiency and outcomes. (Student No. 5)

6.3.2. Uncertain Learning Effects

The students could not have satisfactory learning outcomes when using the program for vocabulary learning. It was less likely to make sure their learning engagement, learning attitudes, and learning behaviours in the program-based learning setting. (Lecturer No. 2)

7. Discussion

7.1. Students’ and Language Teachers’ Perceptions of the WALL Program

7.2. Problems of the WALL Program

7.3. Recommendations for Future WeChat-Based Language Learning and Teaching Programs

8. Limitations and Suggestions

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. 290 Million Students out of School Due to COVID-19: UNESCO Releases First Global Numbers and Mobilizes Response. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/news/290-million-students-out-school-due-covid-19-unesco-releases-first-global-numbers-and-mobilizes (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. An Announcement Regarding “Suspending Classes without Stopping Learning”. 2020. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/202002/t20200212_420385.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Namaziandost, E.; Hashemifardnia, A.; Bilyalova, A.A.; Fuster-Guillén, D.; Palacios Garay, J.P.; Ngoc Diep, L.T.; Ismail, H.; Sundeeva, L.A.; Rivera-Lozada, O. The effect of WeChat-based online instruction on EFL learners’ vocabulary knowledge. Educ. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8825450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Han, J.; Liu, C.; Xu, H. How do university students’ perceptions of the instructor’s role influence their learning outcomes and satisfaction in cloud-based virtual classrooms during the COVID-19 pandemic? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 627443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukulska-Hulme, A.; Shield, L. An overview of mobile assisted language learning: From content delivery to supported collaboration and interaction. Recall 2008, 20, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.P.; Mei, B. Modeling preservice Chinese-as-a-second/foreign-language teachers’ adoption of educational technology: A technology acceptance perspective. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 35, 816–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Crompton, H. Status and trends of mobile learning in English language acquisition: A systematic review of mobile learning from Chinese databases. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2021, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, F.L. New Horizons in MALL Pedagogy: Exploring Tertiary EFL Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices in the Hintherland of the People’s Republic of China. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai International Studies University, Shanghai, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Fan, S.; Wang, Y. Mobile-assisted language learning in Chinese higher education context: A systematic review from the perspective of the situated learning theory. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 9665–9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Chen, J.; Zheng, P.; Wu, Y. Factors affecting EFL teachers’ affordance transfer of ICT resources in China. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 30, 1044–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. China’s higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Some preliminary observations. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. On the lesson design of online college English class during the COVID-19 pandemic. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2020, 10, 1484–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, M. Study on college students’ online learning satisfaction and analysis of the influencing factors during COVID-19: A case study of Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications. Jiangsu Sci. Technol. Inf. 2020, 37, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, L.; Hong, J.C.; Cao, M.; Dong, Y.; Hou, X. Exploring the role of online EFL learners’ perceived social support in their learning engagement: A structural equation model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.G. The effects of gender, educational level, and personality on online learning outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naciri, A.; Baba, M.A.; Achbani, A.; Kharbach, A. Mobile learning in Higher education: Unavoidable alternative during COVID-19. Aquademia 2020, 4, ep20016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, K.M.; Wei, T.; Brenner, D. Remote teaching during COVID-19: Implications from a national survey of language educators. System 2021, 97, 102431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Mezhuyev, V.; Kamaludin, A. Towards a conceptual model for examining the impact of knowledge management factors on mobile learning acceptance. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Z. Mobile-assisted pronunciation learning with feedback from peers and/or automatic speech recognition: A mixed-methods study. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, M. Team-based mobile learning supported by an intelligent system: Case study of STEM students. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, X.; Li, H. Situated game teaching through set plays: A curricular model to teaching sports in physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2018, 37, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesova, D.V.; Moskovkin, L.V.; Popova, T.I. Urgent transition to group online foreign language instruction: Problems and solutions. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2021, 19, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F. Investigating College Students’ English Online Learning Autonomy during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University, Baoding, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.Y.; Huang, F.; Lou, Y.Q.; Chen, S.M. Students’ perceptions of using mobile technologies in informal English learning during the COVID-19 epidemic: A study in Chinese rural secondary schools. J. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 4, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.X.; Luo, J. SWOT analysis of foreign language teaching online under the background of the “COVID–19 Epidemic”: A case study of Kaili University. J. Kaili Univ. 2020, 38, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Adams Becker, S.; Cummins, M.; Davis, A.; Freeman, A.; Hall Giesinger, C.; Ananthanarayanan, V. NMC Horizon Report: 2017 Higher Education Edition; The New Media Consortium: Austin, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Z.; Chen, W.C.; Jia, J.Y.; An, H.L. The effects of using mobile devices on language learning: A meta-analysis. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 1769–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.P. Research on a New Model for Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language Assisted by WeChat. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an International Studies University, Shaanxi, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J. A study on the blended English teaching mode based on live broadcasting under pandemic. J. Qilu Norm. Univ. 2020, 35, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Crosthwaite, P. The affordances of WeChat Voice Messaging for Chinese EFL learners during private tutoring. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 22, 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, V.; Nouri, J. A systematic review of second language learning with mobile technologies. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2018, 13, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, X.J. Qualitative research on lexical fossilized errors in written language of the non-English majors. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Fan, S.; Wang, Y.J.; Lu, J.J. Chinese university students’ experience of WeChat-based English-language vocabulary learning. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.; Cardon, P.; Poddar, A.; Fontenot, R. Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 54, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. Significance of the Web as a Learning Resource in an Australian University Context. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- CNNIC. The 49th China Statistical Report on Internet Development. 2022. Available online: https://www.mpaypass.com.cn/download/202203/16113334.html (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Chiu, Y.H. Computer-assisted second language vocabulary instruction: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2013, 44, E52–E56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Jager, S.; Lowie, W. Narrative review and meta-analysis of MALL research on L2 skills. Recall 2020, 33, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, G.; Hubbard, P. Some emerging principles for mobile-assisted language learning. Int. Res. Found. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2013, 1–15. Available online: http://www.tirfonline.org/english-in-the-workforce/mobile-assisted-language-learning (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Zhang, L.Y. The Design Research of Mini Program of “Educational Technology Theory and Innovation” Course. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Huhhot, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. The Basics of Social Research, 5th ed.; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.F. Applied linguistics: Research Methods and Thesis Writing, 6th ed.; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, M.C.; Bradley, M.A. Data Collection Methods: Semistructured Interviews and Focus Groups. 2009. Available online: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2009/RAND_TR718.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Burns, R.B. Introduction to Research Methods, 4 ed.; Pearson Education: Frenchs Forest, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.J. An Investigation of University Students’ Views about Teaching and Learning English through Their Own Experiences in High Schools and University of Mainland China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.Y. Investigating a m-learning model for college English from the perspective of “AI+Education”. J. Kaifeng Vocat. Coll. Cult. Art 2020, 40, 87–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger, J.S. The social and mobile learning experiences of students using mobile e-books. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2013, 17, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gablinske, P.B. A Case Study of Student and Teacher Relationships and the Effect on Student Learning; Rhode Island College: Providence, Rhode Island, 2014; Available online: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/266 (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Palalas, A. Mobile-assisted language learning: Designing for your students. In Second Language Teaching and Learning with Technology: Views of Emergent Researchers; Thouësny, S., Bradley, L., Eds.; Research Publishing Net: Irvine, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, M.; Taylor, J.; Vavoula, G. Theory of learning for the mobile age. In The SAGE Handbook of e-Learning Research; Andrews, R., Haythornthwaite, C., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; pp. 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- Kozulin, A.; Gindis, B.; Ageyev, V.S.; Miller, S.M. Learning in Doing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kamasak, R.; Özbilgin, M.; Atay, D.; Kar, A. The effectiveness of mobile-assisted language learning (MALL): A review of the extant literature. In Handbook of Research on Determining the Reliability of Online Assessment and Distance Learning; Calimag, M.M.P., Ed.; IGI Global Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Eri, R.; Gudimetla, P.; Star, S.; Rowlands, J.; Girgla, A.; To, L.; Li, F.; Sochea, N.; Bindal, U. Digital resilience in higher education in response to COVID-19 pandemic: Student perceptions from Asia and Australia. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Han, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C. To WeChat or to more chat during learning? The relationship between WeChat and learning from the perspective of university students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 1813–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusa, A.A.; Umar, I.N. A scoping review of critical predictive factors (CPFs) of satisfaction and perceived learning outcomes in E-learning environments. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 1223–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Application of Mobile Phones Apps in College English Vocabulary Learning: A Case of Baicizhan. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Normal University, Xining, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.X.; Zhang, L.J. Teacher learning in difficult times: Examining foreign language teachers’ cognitions about online teaching to tide over COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burston, J. Twenty years of MALL project implementation: A meta-analysis of learning outcomes. Recall 2015, 27, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Academic Faculties/Disciplines/Schools | Students (n = 5) | Teachers (n = 3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | No. 1 | F | Y1 | No. 1 | F |

| Chemistry | No. 2 | M | Y1 | No. 2 | M |

| Information Technology | No. 3 No. 4 | M F | Y1 Y2 | No. 3 | F |

| Media and Communication | No. 5 | F | Y2 | N/A | |

| Q1. What is your opinion of using WeChat for vocabulary learning/teaching? |

| Q2. How is mobile-based vocabulary learning different from the learning/teaching method(s) you have used before? Apart from what has been offered in the WALL program, is there anything else you would expect? |

| Q3. How would you evaluate the WALL program? |

| Q4. Did you like using the WALL program? Why or why not? |

| Q5. How do you like the vocabulary-learning activities you participated in? |

| Q6. What is your opinion of the delivered learning resources? |

| Q7. Could you comment on the three forms of the delivered learning resources (namely texts, audio, and video clips)? |

| Q8. Is there anything you would like to suggest for the WALL program? |

| Q9. How do you think the WALL program has influenced your vocabulary learning/teaching? |

| Q10. How do you think the WALL program has influenced your/students’ motivation for vocabulary learning? |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Students’ and language teachers’ evaluations of the WALL program |

| 76 |

| Theme 2: Advantages of WeChat-based learning approaches |

| 49 |

| Theme 3: Problems of the WALL program |

| 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F. Student and Language Teacher Perceptions of Using a WeChat-Based MALL Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic at a Chinese University. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030236

Li F. Student and Language Teacher Perceptions of Using a WeChat-Based MALL Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic at a Chinese University. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(3):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030236

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fan. 2023. "Student and Language Teacher Perceptions of Using a WeChat-Based MALL Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic at a Chinese University" Education Sciences 13, no. 3: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030236

APA StyleLi, F. (2023). Student and Language Teacher Perceptions of Using a WeChat-Based MALL Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic at a Chinese University. Education Sciences, 13(3), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030236