Abstract

Discovering students’ beliefs and values as regards gender violence is a fundamental factor when attempting to tackle this problem in the sphere of universities. This study presents the validation of a scale for university students’ perceptions of gender-based violence, denominated as the Gender Violence Perception Scale (GVP-S). This scale measures the degree to which the aforementioned perceptions are influenced by gender, the university degree in which participants are enrolled, the type of school to which (i.e., private or state) they attended, and the level of education reached by their parents. The study was carried out with a sample of 1870 students at the University of Cordoba (Spain), and its results revealed that: (1) the GVP-S is well adjusted to and has the optimum psychometric properties for the sample studied, and (2) there are significant differences according to gender, the university degree being studied and the students’ parents’ education, but not the type of secondary education establishment attended. The conclusion that was reached was that it is necessary to carry out more research in this area, to provide preventative measures and training programs regarding gender violence to university students.

1. Introduction

Gender violence can appear in many forms and it is a problem that is the most brutal symbol of the inequality that exists in our society [1,2]. This type of violence is directed toward women for the mere reason that they are women, since their aggressors consider them to lack the minimum rights of freedom, respect, and decision making [3]. At the 4th World Conference in 1995, the United Nations Organization recognized violence toward women as an obstacle to the attainment of the objectives of equality, development, and peace. In addition to violating and destroying the enjoyment of human rights and fundamental liberties. Organic Law 1/2004, of 28 December 2004, and which concerns Integral Protection measures against Gender Violence, is defined as being a declaration of the relations concerning power that have been historically unequal for men and women [4]. The conquest of equality and respect for human dignity and people’s freedom should be a priority objective at all levels of socialization. According to the theoretical review that we have carried out, it is possible to state that gender violence is the result of multiple factors, including learning and culture, and in order to analyze and understand it, it is, therefore, necessary to consider all its dimensions and the social structure in which this phenomenon occurs [5]. Social relations are influenced by the stereotypes of femininity and masculinity that are socio-culturally established and created and, in turn, transmitted from one generation to another. This traditional model of assigned attributes gives much more power to men than to women. In fact, the role of by women in not too distant historical eras was that of inferior beings who were subjugated by men and who were their property. Violence toward women is the most extended type of violence in humanity. The most accepted definition of gender violence is that which appears in Annex II of the First Report of the 4th World Conference on women, which took place in Beijing (Peking) in 1995: “All acts of sexist violence whose possible or real result is physical, sexual or psychological damage” [6]. In this conceptual framework, violence is defined as “physical or psychological coercion exercised over a person in order to invalidate their wishes and oblige them to carry out a particular act” [7]. We have followed the suggestion of Gallardo-López and Gallardo and classified gender violence by taking into consideration two principal criteria: the environment in which this violence takes place and the different ways in which it manifests itself in a couple [8].

This study focuses on violence against women in the context of relationships within couples. It specifically analyzes the perception that university students have of situations of risk within the couple that lead to gender violence against women. Knowing these beliefs and detecting the students’ values concerning gender violence is fundamental as regards tackling this subject in the university environment. Organic Law 1/2004 states that some of the objectives of the education system should be education regarding fundamental rights and liberties, and equality between men and women, along with the exercising of tolerance and freedom within the democratic principles of coexistence. Its principles regarding quality should similarly include the elimination of those obstacles in order to attain full equality between men and women, and education with which to prevent conflicts and for their peaceful resolution [4]. Universities should understand and foment the transversal education, teaching of and research into gender equality and non-discrimination in all their academic environments, because gender violence is a problem that is present in all spheres of society, including universities. This has been demonstrated in numerous national and international research works [2,9], which state the need for preventative measures, attention, and eradication in the university context.

Students’ perceptions of gender violence are influenced by many factors, of which it is possible to highlight their family environment, the information that they receive via different means of communication, the degree that they are studying, their gender, and the education that they receive throughout their lives [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. These may, owing to their parents’ possible sexist conceptions and attitudes, mark their future interpersonal relationships. According to the study carried out by Vara-Horna et al. [11], 65% of students have been harmed by their current or ex partners, with psychological violence predominating over physical violence and having negative effects on their academic performance and, in the majority of cases, resulting in them giving up their degree. With regard to gender, men have a fundamentally greater tendency to blame female victims for the violence they have suffered, while women attribute responsibility to the person who committed the abuse and consider violent incidents to be more serious [12,13,14,15]. Males similarly tend to condone the use of violence against their partners and to agree with the existence of masculine privileges to a greater extent than women [16,17]. For example, when studying a group of adolescents, Díaz-Aguado observed that the women rejected the use of violence in any circumstance to a much greater extent than men, while the men tended to justify it [18]. In fact, 15% of the boys interviewed considered that the victim of violence is, in part, to blame for the situation. In their study, Yanes and González similarly observed that students with more traditional beliefs as regards the social and family role of women find women to be more responsible for conflicts within couples than do those who have a less traditional view of these roles [19]. However, no differences have been observed as regards other aspects of these conflicts, such as the perception of their frequency and gravity, or the males’ responsibility for these conflicts. In short, it has been detected that men and people with traditional attitudes toward gender roles generally tend to have positive attitudes toward violence against the women in couples, when compared to women and people whose attitudes toward gender roles are egalitarian.

The study on sexism and gender violence carried out by Rottenbacher found significant differences according to the type of degree that had been studied, with the balance being tipped in favor of Social Science students when compared to Science and Engineering students. With regard to the university at which they were studying, the same authors found that students at state universities were more likely to discriminate against women than those at private universities, i.e., sexism is mediated by the socio-economic and social/family situation [20]. They also concluded that men have more prejudices than women, and that their ideas are more sexist, and they attribute certain roles to women. These results are similar to those found in other research, and it is thus reasonable to assume that sexism is a risk factor that plays a role in violent behavior toward women [2,3,5,6,21,22].

Another factor that has been related to the attitudes regarding violence toward the women in couples is the parents’ level of education. For example, Yoshioka et al., observed that between 24 and 36% of a sample of Higher Education students from four universities justified violence in a couple under certain circumstances, with the education they had received and their parents’ academic education being the only demographic predictor in the research, such that the higher the level of the parents’ education, the lower the level of justification, and vice versa [17].

Although this result may be encouraging as regards preventing this problem, there is not always a correlation, since a high level of education does not guarantee the presence of unfavorable attitudes concerning violence toward the women in couples [23].

There are numerous scales with which to evaluate the different dimensions and constructs of gender violence [24,25,26,27], but not all of them contemplate the repercussions that the education received in and culture of the family environment may have on students’ perceptions of gender violence [2,17,28]. This study presents the validation of a scale with which to evaluate university students’ perceptions of gender violence. This scale measures the degree to which these perceptions are influenced by gender, the degree being studied, the type of secondary education establishment that the students attended (state or private), and the students’ parents’ academic education. There are numerous scales to assess different dimensions of gender violence.

2. The Present Study

Taking into account the above, the following objectives were proposed:

Objective 1:

To analyze the psychometric properties of the Gender Violence Perception Scale (GVP-S).

Objective 2:

To evaluate university students’ perceptions of gender violence according to their gender, the degree they are studying, the type of secondary education establishment that they attended (state or private) and their parents’ academic education.

With regard to these objectives, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1:

The Gender Violence Perception Scale (GVP-S) has a good fit and has the optimum psychometric properties for the sample studied.

Hypothesis 2:

Women will have a greater perception of situations in which there is violence toward women.

Hypothesis 3:

Social Science degree students will have a greater perception of situations in which there is violence toward women.

Hypothesis 4:

The students will have similar perceptions of gender violence, regardless of the type of secondary education establishment that they attended.

Hypothesis 5:

University students’ greater perceptions of situations in which gender violence occurs will be related to their parents’ higher levels of academic education.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

The participants were a total of 1870 students at the University of Cordoba (Spain). The procedure followed to select the sample was incidental and based on accessibility. Participants belonged to undergraduate courses whose teaching staff made a commitment to collaborate with the research project. Consequently, the students enrolled in the aforementioned courses were the subjects from whom the data was gathered.

Those degree programs in which the teachers committed themselves to collaborate with the research participated. In addition, all students who were in the classroom during data collection participated.

The sample was eventually divided into two sub-samples: a first sample corresponding to an exploratory study composed of 220 students, and a second sample made up of 1650 students, which corresponded to the confirmatory study. Of these students, 25.1% were male and 74.9% were female, and their ages ranged between 17 and 59 (M = 20.88; D.T = 3.606).

3.2. Instruments

Information was obtained through the use of an ad hoc questionnaire composed of the participants’ socio-demographic data (e.g., gender, parents’ level of studies) and questions regarding possible first-hand experiences of gender violence. These gender violence-related variables measured the degree to which the participants knew someone who had suffered something related to gender violence or sexual harassment (e.g., “threatening/intimidating e-mails or text messages”). This instrument was presented by means of a unifactorial 12-item Likert-type scale (see Table 1) on which the scores varied between 1 (Never) and 5 (Always).

Table 1.

Items on the Gender Violence Perception Scale (GVP-S).

3.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

Data collection was carried out by first contacting each of the university departments in order to provide information and obtain consent for participation in the research. Once consent had been obtained, the participants were asked to fill in the questionnaires, which took approximately 30 min. The participants, all of whom were adults, provided their informed consent in writing and were informed about the voluntary nature of responding to the questionnaire and that the data provided would be treated in an anonymous and confidential manner. Any doubts that arose were dealt with, and data collection took place without any incidents. The process was followed in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Helsinki Declaration.

The development procedure employed to carry out the study took place in two different phases. The purpose of the first phase, which was of an exploratory nature, was to examine the factorial structure of the instrument. More specifically, the Factor 10.9.02 program was used to carry out an Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA) with the objective of determining the number of underlying factors. The purpose of the second phase, which was of a confirmatory nature, was to validate the factorial structure of the instrument examined in the previous phase, to analyze its psychometric properties and to apply it [29]. This was done using a Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) and by employing the EQS 6.2 program.

Since an absence of normality was detected in the first phase, the Robust Estimation Method was employed. The modal’s fit was interpreted by employing Satorra–Bentler’s chi squared (x2S-B) and x2S-B/df. Other indices not affected by the sample size were also considered, such as the NNFI; NFI; CFI, and IFI, where values of ≤ 0.95 were employed as criteria with which to assume a good fit [30,31]. Finally, values of between 0.05 and 0.08 for the RMSEA were also considered to indicate that the model had a good fit.

A descriptive and comparative analysis was also carried out in the second phase, using the SPSS 20 program. The Mann–Whitney U test was employed in order to determine any differences among violent situations according to sex and type of secondary education establishment attended. Moreover, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to verify the existence of differences in the perception of violent situations according to the degree being studied and the parents’ level of academic education. The level of confidence was 95% (p < 0.05) and 99% (p < 0.01), depending on the case.

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factorial Analysis of the GVP-S

The results obtained from the EFA, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = 0.897) and the Bartlett–Sphericity Test (Bartlett Test = 1234.988; p < 0.01) indicated that the sample was ideal to be able to carry out the CFA. Table 2 shows the descriptions of each item, along with their factorial weights.

Table 2.

Univariant descriptive analyses, factorial weights and EFA communities.

4.2. Confirmatory Factorial Analysis of the GVP-S

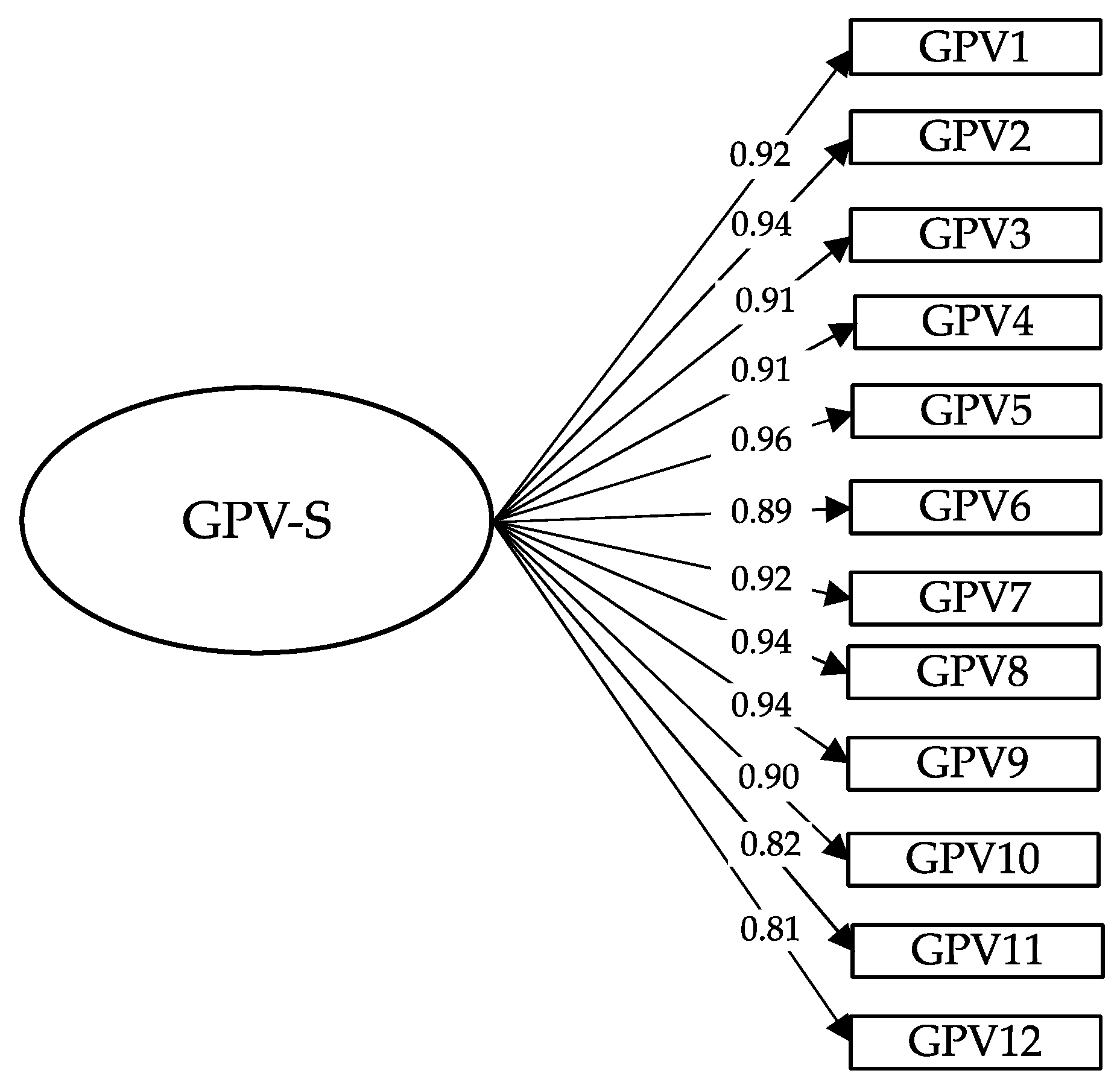

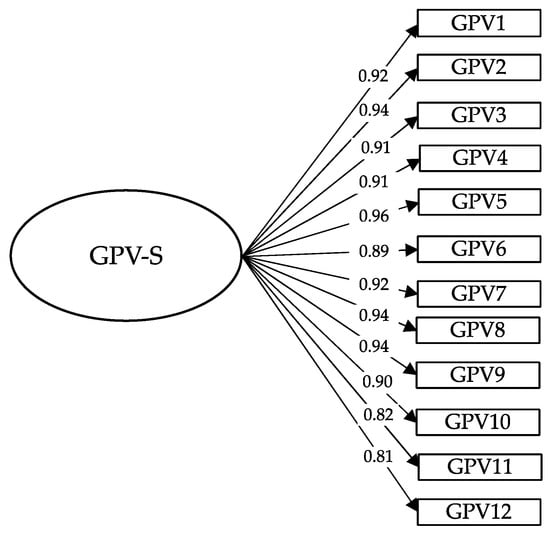

The robust maximum verisimilitude estimation method was employed in the second phase owing to the fact that the data lacked the normality required to be able to use a unifactorial model (see Figure 1). The various goodness of fit indices of the model were considered suitable: x2S-B = 524.3078; p = 0.00 [32]. Those that evaluated the relative fit of the model and those that were not affected by the sample size had high values, indicated their fit to the model: NFI = 0.961; NNFI = 0.957; CFI = 0.965; IFI = 0.965; RMSEA = 0.074.

Figure 1.

CFA Model for GVP-S.

The polychoric correlations among the items of which the scale is composed were positive (Table 3). Moreover, the indices obtained for reliability and internal consistency were considered to be satisfactory for the instrument in general (α = 0.899).

Table 3.

Matrix of polychoric correlations among GVP-S items.

4.3. Application of GVP-S: Evaluating University Students’ Perceptions of Gender Violence According to Gender, Degree Studied, Type of Secondary Education Establishment Attended (State or Private) and Parents’ Academic Education

The results of the Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples obtained for the comparison of gender as regards the participants’ perceptions of gender violence revealed that the women obtained higher scores than the men for most of the items (see Table 4). The women scored significantly higher than the men in all cases, except for the perception of uncomfortable situations or fear of feeling harassed and intimidated, and in situations in which there are obscene comments, rumors or attacks with relation to one’s sex life. Both men and women obtained similar scores in these cases.

Table 4.

Results regarding comparison of perception of gender violence according to gender.

Regarding the type of studies (see Table 5), those participants enrolled in the degree in Labor Relations and Human Resources had a significantly lower perception of feelings of position or jealousy (GVP1) when compared to those enrolled in the degrees in Early Childhood Education, Social Education, and Psychology. The same happened with those studying for degree in Primary Education with regard to those studying Infant Education and Social Education in the case of this item.

Table 5.

Results regarding comparison of perception of gender violence according to degree being studied.

In the case of receiving threatening e-mails or text messages (GVP3) and sexist comments (GVP6), the students on Social Education degrees obtained a higher level of perception than those on Labor Relations and Human Resources, Infant Education, Primary Education degrees, and the Joint Honors in Tourism and Translation degree. Those studying Primary Education had a lower perception than those studying Psychology and Infant Education; and the same occurred in the case of Labor Relations and Human Resources with respect to Psychology.

Psychological aggression (GVP5) was also perceived to a greater extent by the future Social Educators than by the Psychology, Infant Education, Primary Education, and Master’s degree students, as also occurred with feeling uncomfortable or the fear of feeling harassed and intimidated (GVP9) with respect to the Psychology, Infant Education, Primary Education and Labor Relations, and Human Resources students. The students on the Psychology degree also obtained lower scores for this item than those studying Tourism and Translation. Moreover, the future psychologists had a lower perception of situations that implied preferential treatment or better grades in return for sexual favors (GVP11) than did the students on other degrees.

The results concerning the type of Secondary Education establishment attended were not different for any of the items (see Table 6). The students who had attended state schools (those that receive economic support from the state) and the students who had attended private schools (those financed by the pupils’ parents) obtained similar scores as regards their perceptions of situations related to gender violence.

Table 6.

Results regarding comparison of perception of violent situations according to Secondary Education establishment attended.

With regard to the parents’ academic education (see Table 7), those people whose parents had a medium level of academic education (secondary education and vocational training) had a greater perception of situations related to hearing sexist comments than those whose parents had a high level of education (university and post-university education).

Table 7.

Results regarding comparison of perceptions of violent situations according to parents’ level of academic education.

In the case of the mothers’ academic education (see Table 8), those students whose mothers had not received any academic education (no studies) had a greater perception of situations related to psychological aggression than those whose mothers had any level of academic education, be it low (primary), medium (secondary), or high (university and post-university).

Table 8.

Results regarding comparison of perceptions of violent situations according to mother’s level of academic education.

5. Discussion

When evaluating gender violence in the university environment, few authors have designed and analyzed scales with which to measure students’ thoughts and beliefs in this context. The principal objective of this study has, therefore, been to verify whether the GVP-S might be a good instrument with which to do so. According to the results obtained after carrying out the psychometric analyses detailed above, the GVP-S has indices of reliability and consistency that make it highly recommendable for this purpose, and the first hypothesis proposed in this research is, therefore, confirmed. Previous studies have analyzed scales with which to evaluate gender violence, as is the case of the Abuse Risk Inventory (ARI), whose fundamental purpose is to identify women who are currently victims of abuse and who are at risk from their partners or ex-partners [33]. The Emotional Abuse Scale (EAS) is a scale that evaluates emotional abuse during courtship, with 54 items grouped into 4 factors: hostile deprivation, dominance/intimidation, degradation, and restrictive control [34]. This instrument can be adapted to people of both sexes with regard to their partners. There is also the Partner Abuse Scale, Non-Physical (PASNP) [35], a 25-item scale that evaluates the magnitude of non-physical abuse perceived by the partner, and which is intended for people who are in a relationship, co-habiting, or married [36]. All of these studies have been carried out with the attainment of tools with which to measure the different constructs and dimensions surrounding violence toward women and have optimum qualities.

Moreover, with regard to the study presented herein, the research concludes that women perceive situations in which there is a greater risk of gender violence, psychological aggression, control (over the activities carried out, the company kept), jealousy (feeling of possession), threatening and/or intimidating e-mails, and text messages, etc., in a more significant manner than do men [18,19,36]. The second hypothesis proposed in this study is, therefore, confirmed, since the women surveyed had a greater perception of violent situations for women than did the men.

In the case of the degrees that the participants were studying, this research supports the results obtained in previous studies [6,37]. These studies coincide with our results, since the students studying for degrees in education are more sensitive as regards detecting situations that may induce men to commit acts of violence against women. More specifically, the students on Social Education and Primary Education degrees appreciated this type of situation to a greater extent. It is, therefore, possible to confirm the third hypothesis which states that people studying for Social Science degrees have a greater perception of gender violence.

The fourth hypothesis is confirmed because students showed similar perceptions of gender-based violence, regardless of the type of high school establishment that they attended. However, different results have been found in another research. Carrasco-Lozano and Veloz-Méndez conducted a research in Mexico to identify the way in which students from a state school and students from an independent Christian school learnt values. The conclusions of this study were that values are learnt according to the type of school, and that gender also determines the perception of these values [38]. In this regard, the study also proves the importance of teachers’ idiosyncrasy and practices [39,40].

Parents are a fundamental pillar as regards the values that they instill in their children, and their academic education is consequently an important variable in the educational criteria they use and the relationship that is established between them [11,16,18]. However, the conclusion reached after carrying out our study was that those students whose parents have a medium level of education (secondary education and vocational training) are more sensitive to sexist and obscene comments and rumors or attacks concerning their sex lives than those whose parents have a high level (university and post-university) of academic education. The fifth hypothesis is, therefore, only partially corroborated, since a greater perception of gender violence situations is felt by those university students whose parents have a lower level of academic education. Moreover, in the case of mothers, the lower their academic education, the greater their children’s perception of gender violence.

The results of this research show that those students whose mothers have no academic education (no studies) are more sensitive to situations related to psychological aggression toward women when compared to the students whose mothers have any other level of academic education, be it low, medium, or high. These results coincide with those obtained in the studies by different authors [2,10,19,28,41], in which neither the students’ socio-economic level nor their socio-educative level significantly correlated with their beliefs and values [42].

6. Conclusions

The results shown in this paper contribute to showing the importance of carrying out research into gender violence and sexual harassment in the university context. The similarities between this study and the existing literature lead us to propose the design of research tools that will analyze and evaluate the dimensions and constructs related to violence toward women. This study contributes to the literature by providing an instrument to measure students’ thoughts and beliefs about gender-based violence. The E-PVG can be considered an optimal and reliable scale for this purpose.

The parallelism found with other research reveals the difference between men and women as regards their perceptions of situations in which there is a greater or lesser risk of gender violence occurring in couples. Women perceive more risky situations for gender-based violence than men (psychological aggression, control, jealousy, etc.).

Another finding is that students of education degrees show greater sensitivity to detect situations that may induce men to commit violence against women. In addition, students show similar perceptions of violence, regardless of the type of School in which they had been previously enrolled.

The role of parents is crucial when it comes to value and education. Parents’ level of education is related to their sensitivity to this type of violence. For illustrative purposes parents with a medium level of academic studies are more sensitive to sexist, obscene comments, rumors or attacks on sexual life, compared to parents with a high level of academic education. It is also important to emphasize that for the very case of mothers, the unschooled ones tend to be more sensitive towards situations linked to psychological aggression against women.

The research shown herein also identifies the need to implement actions and programs directed toward preventing sexist behavior and attitudes in university students.

It is necessary to highlight the importance of the students’ cultural context and the context of their families since their parents’ academic education and the educational guidelines they provide affect their perceptions of situations in which gender violence occurs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O.-R. and M.I.A.; methodology, M.I.A. and I.D.; software, I.D.; formal analysis, I.D.; investigation, M.O.-R., M.I.A. and I.D.; resources, M.O.-R.; data curation, M.O.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O.-R., M.I.A. and I.D; writing—review and editing, I.D.; project administration, M.O.-R. and M.I.A.; Funding acquisition, M.O.-R. and M.I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Proyectos de I+D+i en el marco del Programa Operativo FEDER Andalucía 2014–2020. Proyecto Impulsa2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions privacy.

Acknowledgments

To the collaborators of the Intercultural Chair “Córdoba Ciudad de Encuentro “ of the University of Cordoba.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Maquibar, A.; Estalella, I.; Vives-Cases, C.; Hurtig, A.K.; Goicolea, I. Analysing Training in Gender-Based Violence for Undergraduate Nursing Students in Spain: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 77, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuna-Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez-Osuna, L.M.; Dios, I.; Amor, M.I. Perception of gender-based violence and sexual harassment in university students: Analysis of the information sources and risk within a relationship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharoni, S.; Klocke, B. Faculty Confronting Gender-Based Violence on Campus: Opportunities and Challenges. Violence Women 2019, 25, 1352–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marugán Pintos, B. Límites de la utilización del concepto ‘violencia de género’ en la Ley Orgánica 1/2004 para actuar contra el acoso sexual. J. Fem. Gend. Women Stud. 2015, 1, 53–61. Available online: https://revistas.uam.es/revIUEM/article/view/411 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Torralbo, M.; Garrido, B.; Hidalgo, M.; Sábado, T. Diseño y validación de un instrumento para medir actitudes machistas, violencia y estereotipos en adolescentes. Metas De Enfermería 2018, 21, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Diéguez Méndez, R.; Martínez-Silva, I.M.; Medrano Varela, M.; Rodríguez-Calvo, M.S. Creencias y actitudes del alumnado universitario hacia la violencia de género. Educ. Médica 2020, 21, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito, F. Violencia de género. Mente Y Cereb. 2011, 48, 20–25. Available online: https://www.uv.mx/cendhiu/files/2013/08/Articulo-Violencia-de-genero.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Gallardo-López, J.A.; Gallardo Vázquez, P. Educar en igualdad: Prevención de la violencia de género en la adolescencia. Rev. Educ. Hekademos 2019, 26, 31–39. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6985275 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Pozo, C.; Martos, M.J.; Alonso, E. ¿Manifiesta actitudes sexistas el alumnado de enseñanza secundaria? Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 8, 541–560. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, H. La prevención de la violencia de género en adolescentes. Una experiencia en el ámbito educativo. Apunt. Psicol. 2007, 25, 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, A.A.; Asencios-Gonzalez, Z.B.; McBride, J.B. Does Domestic Violence against Women Increase Teacher-Student School Violence? The Mediating Roles of Morbidity and Diminished Workplace Performance. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, NP17979–NP18005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, L.M.; Richman, C.L. Attitudes toward domestic violence: Race and gender issues. Sex Roles 1999, 40, 227–247. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1018898921560 (accessed on 10 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.J.; Cook, C.A. Attributions about spouse abuse: It matters who the batterers and victims are. Sex Roles 1994, 30, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, M.; Byrne, C.A.; Mutsumi, M.; Abraham, A.G. Attitudes toward violence against women: A cross-nation study. Sex Roles 2003, 49, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; Harris, R.J. The effect of provocation, ethnicity and injury description of men’s and women’s perceptions of a wife- battering incident. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, F.E. Attitudes and family violence: Linking intergenerational and cultural theories. J. Fam. Violence 2001, 16, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, M.R.; DiNoia, J.; Ullah, K. Attitudes toward Marital Violence: An Examination of Four Asian Communities. Violence Women 2001, 7, 900–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Aguado, M.J. Adolescencia, sexismo y violencia de género. Pap. Del Psicólogo 2003, 23, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yanes, J.M.; González, R. Correlatos cognitivos asociados a la experiencia de violencia interparental. Psicothema 2000, 12, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenbacher, J.M. Sexismo ambivalente, paternalismo masculino e ideología política en adultos jóvenes de la ciudad de Lima. Pensam. Psicológico 2010, 14, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Nuñez, J.; Derluyn, I.; Valcke, M. Student Teachers’ Cognitions to Integrate Comprehensive Sexuality Education into Their Future Teaching Practices in Ecuador. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 79, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale Development Research: A Content Analysis and Recommendations for Best Practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.A.; Hampson, S.C.; Ackerman, A.R. Sexual and Relationship Violence Prevention and Response: What Drives the Commuter Campus Student Experience? J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP11421–NP11445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.B.; Schmidt, G.; Lent, B.; Sas, G.; Lemelin, J. Screening for violence against women. Validation and feasibility studies of a French screening tool. Can. Fam. Physician Med. Fam. Can. 2001, 47, 988–995. [Google Scholar]

- Lemus Martín, S.; Castillo, M.; Moya, M.; Padilla García, J.L.; Ryan, E. Elaboración y validación del Inventario de Sexismo Ambivalente para Adolescentes. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2008, 8, 537–562. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=33712001013 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Moya, M.; Expósito, F.; Padilla, J.L. Revisión de las propiedades psicométricas de las versiones larga y reducida de la Escala sobre Ideología de Género. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2006, 6, 709–727. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.; Basile, K.C.; Hertz, M.F.; Sitterle, D. Measuring Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Perpetration: A Compendium of Assessment Tools; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cubells, J.; Calsamiglia, A. Romantic love’s repertoire and the conditions of possibility of violence against women. Psychology 2015, 14, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, Development and Future Directions. Psicothema 2017, 29, 236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegidis, B.L. Abuse Risk Inventory Manual; Consulting Psychologist Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C.M.; Hoover, S.A. Measuring Emotional Abuse in Dating Relationships as a Multifactorial Construct. Violence Vict. 1999, 14, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, W.W. The WALMYR Assessment Scales Scoring Manual; WALMYR Publishing Company: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C.J.A.; Menke, J.M.; O’Hara Brewster, K.; Figueredo, A.J. Validation of a measure of intimate partner abuse with couples participating in divorce mediation. J. Divorce Remarriage 2009, 50, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS 6 Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software, Inc.: Temple, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer Pérez, V.A.; Bosch Fiol, E.; Palmer, M.C.; Torres Espinosa, G.; Navarro Guzmán, C. La violencia contra las mujeres en la pareja: Creencias y actitudes en estudiantes universitarios/as. Psicothema 2006, 18, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco Lozano, M.E.E.; Veloz Méndez, A. Aprendiendo valores desaprendiendo violencia, un estudio con niñas y niños de escuelas de educación básica en el estado de Hidalgo. Ra Ximhai 2014, 10, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobernado Arribas, R. Consecuencias ideacionales del tipo de escuela (pública, privada religiosa y privada laica). Rev. Pedagog. 2003, 226, 439–458. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, G.; Alfonso Vergara, M. Factores que determinan la elección de carrera profesional: En estudiantes de undécimo grado de colegios públicos y privados de Barrancabermeja. Rev. Psicoespacios 2018, 12, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Osuna, L.M. Análisis de la Percepción Sobre la Violencia de Género y Acoso por Razón de sexo en la Universidad. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Córdoba (España), Córdoba, Spain, 2021. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10396/21584/2021000002313.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Melendez-Rhodes, T.; Košutić, I. Evaluation of Resistance to Violence in Intimate Relationships: Initial Development and Validation. Violence Women 2021, 27, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).