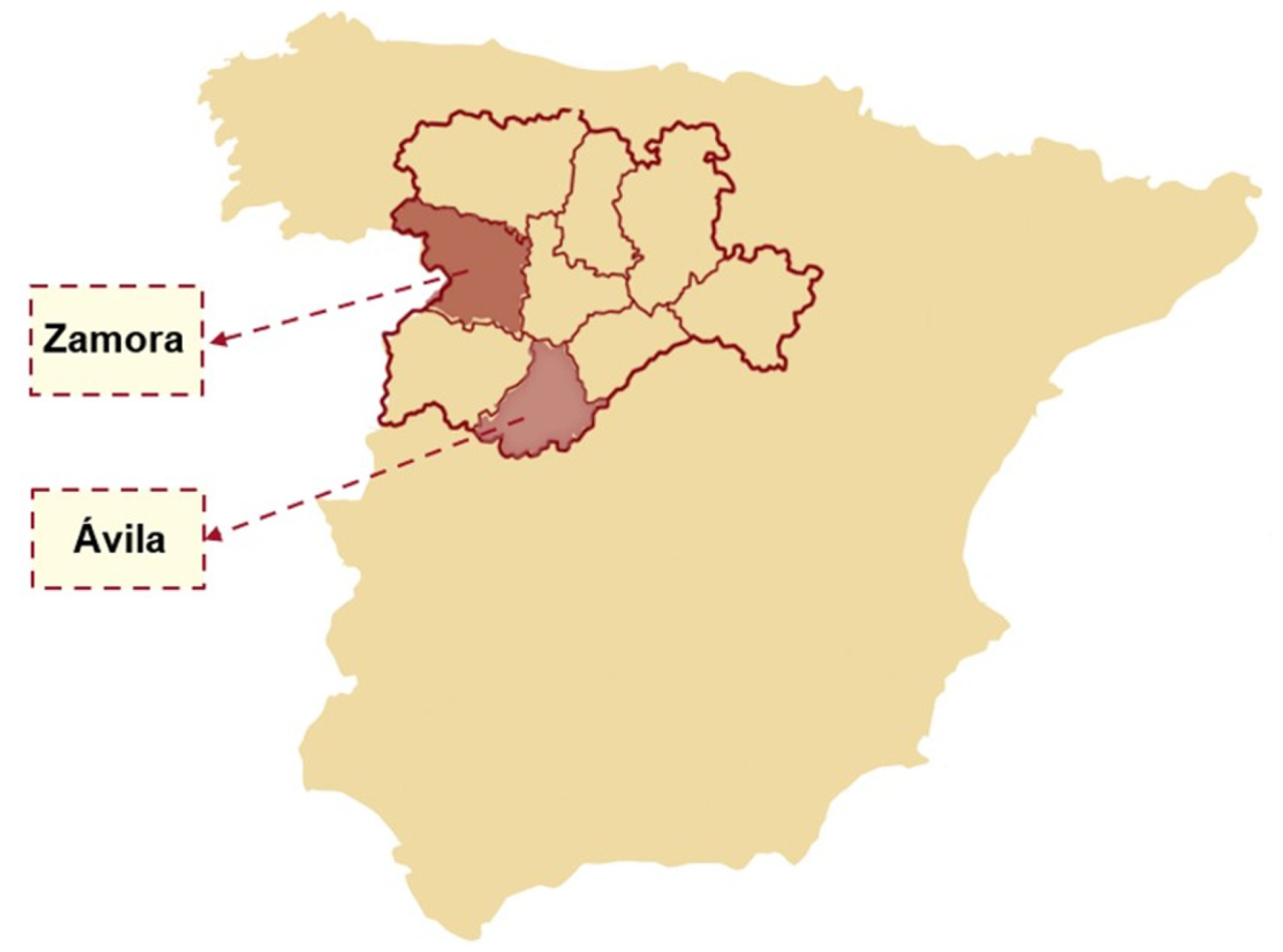

Incidence of Bullying in Sparsely Populated Regions: An Exploratory Study in Ávila and Zamora (Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Notion of Bullying and Its Incidence in the Post-Pandemic Situation

2.2. The Incidence of Bullying in Urban vs. Rural Areas

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Objectives and Variables

3.3. Instrument

3.4. Design and Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Attawell, K. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying; Education 2030; United National, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oksendal, E.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Wolke, D.; Helland, S.S.; Holte, A.; Wang, M.V.; Brandlistuen, R.E. Associations between Language Difficulties, Peer Victimization, and Bully Perpetration from 3 through 8 Years of Age: Results from a Population-Based Study. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2021, 64, 2698–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaghan, L.F. Civilising Recalcitrart Boys’ Bodies: Pursuing Social Fitness through the Anti-obesity Offensive. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.T.; Schmitz, R.M. Bullying at School and on the Street: Risk Factors and Outcomes among Homeless Youth. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 26, NP4768–NP4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sule-Tepetas, G.; Akgun, E.; Akbaba-Altun, S. Identifying Preschool Teachers’opinion about Peer Bullying. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 1675–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, I.; Montesó-Curto, P.; Metzler Sawin, E.; Jiménez-Herrera, M.; Puig-Llobet, M.; Seabra, P.; Toussaint, L. Risk Factors for Teen Suicide and Bullying: An International Integrative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2021, 27, e12930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.U.; Reidy, D. Bullying and Suicide Risk among Sexual Miniority Youth in the United States. Prev. Med. 2021, 153, 106728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azúa-Fuentes, E.; Rojas-Carvallo, P.; Ruiz-Poblete, S. Bullying as a Risk Factor for Depression and Suicide. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2020, 91, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, R.; Maughan, B.; Arseneault, L. Adult Health Outcomes of Childhood Bullying Victimization: Evidence from a Five- Decade Longitudinal British Birth Cohort. Amer. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.C.; Huang, M.F.; Wu, Y.Y.; Hu, H.F.; Yen, C.F. Pain, Bullying Involvement, and Mental Health Problems among Children and Adolescents with ADHD in Taiwan. J Atten. Disord. 2019, 23, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Solís, A.; Moreta-Herrera, R. Victims of Cyberbullying and its Influence on Emotional Regulation Difficulties in Adolescents in Ecuador. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2022, 14, 67–75. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10256/21059 (accessed on 19 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, A.B.; Galve-González, C.; Cervero, A.; Tuero, E. Cyberbullying in First-year University Students and its Influence on their Intentions to Drop out. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, E. You’ve got the Disease: How Disgust in Child Culture Shapes School Bullying. Ethnogr. Educ. 2021, 16, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.; Buendía, L.; Fernández, F. Grooming, Cyberbullying and Sexting in Chile According of Sex and School Management or Administrative Dependency. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2018, 89, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacampa, C.; Pujols, A. Effects of and Coping Strategies for Stalking Victimisation in Spain: Consequences for its Criminalisation. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2019, 56, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSouza, E.R.; Ribeiro, J. Bullying and Sexual Harassment Among Brazilian High School Students. J. Interpers. Violence 2005, 20, 1018–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieno, A.; Gini, G.; Santinello, M. Different Forms of Bullying and Their Association to Smoking and Drinking Behavior in Italian Adolescents. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Randall, D.P.; Ambrose, A.; Orand, M. ‘I was Bullied Too’: Stories of Bullying and Coping in an Online Community. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, J.M.; Jiménez-Blanco, A.; Artola, T.; Sastre, S.; Azañedo, C.M. Emotional Intelligence and the Different Manifestations of Bullying in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zequinão, M.A.; Medeiros, P.; Oliveira, W.A.; Santos, M.A.; Lopes, L.C.O.; Pereira, B. Body Dissatisfaction and Bullying among Underweight Schoolchildren in Brazil and Portugal: A Cross-Cultural Study. J. Hum. Growth Dev. 2022, 32, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagihan-Tanik, Ö.; Nezih, Ö.; Hasan, Ç. An Investigation of Cyberbullying and Cyber-Victimization of Mathematics and Science Pre-Service Teachers. Malays. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 8, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaç, B.; Yurt, E.; Aydin, M.; Kaşarci, I. Predictive Relationship between Humane Values of Adelescents Cyberbullying and Cyberbullying Sensibility. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 14, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Mayea, Y.; Díaz, A.P.; Gómez, R. Bullying Behaviors as a Form of Violence in Times of Pandemic and Impact on Mental Health. Rev. Cuba. De Pediatría 2022, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Lessard, L.M.; Puhl, R.M. Adolescent Academic Worries Amid COVID-19 and Perspectives on Pandemic-related Changes in Teacher and Peer Relations. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyobe, M.E.; Mimbi, L.; Nembandona, P.; Mtshazi, S. Mobile Bullying Among Rural South African Students: Examining the Applicability of Existing Theories. Afr. J. Inf. Syst. 2018, 10, 1. Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ajis/vol10/iss2/1 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Rodríguez-Álvarez, J.M.; Navarro, R.; Yubero, S. Bullying/Cyberbullying en Quinto y Sexto Curso de Educación Primaria: Diferencias entre Contextos Rurales y Urbanos. Psicol. Educ. 2022, 28, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebollero-Salinas, A.; Orejudo, S.; Cano-Escoriaza, J.; Íñiguez-Berrozpe, T. Cyvergossip and Problematic Internet Use in cyberaggression and cybervictimization among adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 131, 107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.R.; Granados, C.F.; Iglesias, C.M.; Guevara Pérez, J.C. Descriptive Study of Cybervictimization in a Sample of Compulsory Secondary Education Students. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 25, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelio, C.; Rodríguez-González, P.; Fernández-Río, J.; González-Villora, S. Cyberbullying in Elementary and Middle School Students: A Systematic Review. Comput. Educ. 2022, 176, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravaca-Sánchez, F.; Falcón-Romero, M.; Navarro-Zaragoza, J.; Ruiz-Cabello, A.L.; Frantzisko, O.R.; Maldonado, A.L. Prevalence and Patterns of Traditional Bullying Victimization and Cyber-teasing among College Population in Spain. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravaca-Sánchez, F.; Navarro-Zaragoza, J.; Luna-Ruiz-Cabello, A.; Falcón-Romero, M.; Luna-Maldonado, A. Association between Bullying Victimization and Substance Use among College Students in Spain. Adicciones 2016, 29, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Costa-Martins, M.; Silva, B.; Ferreira, E.; Nunes, O.; Castro-Caldas, A. How Different are Girls and Boys as Bullies and Victims? Comparative Perspectives on Gender and Age in the Bullying Dynamics. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 11, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Mazzucco, W.; Scarpitta, F.; Ventura, G.; Marotta, C.; Bono, S.E.; Arcidiacono, E.; Gentile, M.; Sannasardo, P.; Gambino, C.R.; et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Bullying Phenomenon among Pre-adolescents Attending First-grade Secondary Schools of Palermo, Italy, and a Comparative Systematic Literature Review. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorent, V.J.; Diaz-Chaves, A.; Zych, I.; Twardowska-Staszek, E.; Marín-López, I.; Díaz-Chaves, A. Bullying and Cyberbullying in Spain and Poland, and Their Relation to Social, Emotional and Moral Competencies. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 13, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClanahan, M.; McCoy, S.M.; Jacobsen, K.H. Forms of Bullying Reported by Middle-school Students in Latin America and the Caribbean. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2015, 8, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ren, J.; Li, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. School Bullying Among Vocational School Students in China: Prevalence and Associations with Personal, Relational, and School Factors. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP104–NP124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmy, P.; Vilhjálmsson, R.; Kristjánsdóttir, G. Bullying in School-aged Children in Iceland: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 38, e30–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagintsev, R.; Pinskaya, M.; Konstantinovskiy, D.; Kosaretsky, S. The Contradictions of Education in Russia. In Rural Youth at the Crossroads; Schafft, K.A., Stanić, S., Horvatek, R., Maselli, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulby, D.; Jones, C.; Harris, D. World Yearbook of Education 1992; Urban Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smorti, A.; Menesini, E.; Smith, P.K. Parents’ Definitions of Children’s Bullying in a Five-Country Comparison. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2003, 34, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. The Relationship of Aggression and Bullying to Social Preference: Differences in Gender and Types of Aggression. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2009, 33, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornu, C.; Abduvahobov, P.; Laoufi, R.; Liu, Y.; Séguy, S. An Introduction to a Whole-Education Approach to School Bullying: Recommendations from UNESCO Scientific Committee on School Violence and Bullying Including Cyberbullying. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2022, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.C.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S. Bullying/Cyberbullying in Secondary Education: A Comparison Between Secondary Schools in Rural and Urban Contexts. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Fernández, M.-V.; Lameiras-Fernández, M.; Rodríguez-Castro, Y.; Vallejo-Medina, P. Bullying Among Spanish Secondary Education Students: The Role of Gender Traits, Sexism, and Homophobia. J. Interpers. Violence 2013, 28, 2915–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchante, M.; Coelho, V.A.; Romão, A.M. The Influence of School Climate in Bullying and Victimization Behaviors during Middle School Transition. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 71, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, H.; Hayer, T.; Petermann, F.; Jugert, G. Physical, Verbal, and Relational Forms of Bullying among German Students: Age Trends, Gender Differences, and Correlates. Aggr. Bevav. 2006, 32, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, R.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S. Bullying-victimization Problems and Aggressive Tendencies in Spanish Secondary Schools Students: The Role of Gender Stereotypical Traits. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2011, 14, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wu, S.; Twayigira, M.; Luo, X.; Gao, X.; Shen, Y.; Long, Y.; Huang, C.; Shen, Y. Prevalence and Associated Factors of School Bullying among Chinese College Students in Changsha, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Víllora, B.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S.; Alfaro, A.; Navarro, R. Relations among Poly-Bullying Victimization, Subjective Well-Being and Resilience in a Sample of Late Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaux, E.; Castellanos, M. Money and Age in Schools: Bullying and Power Imbalances. Aggr. Behav. 2015, 41, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, E.; Murgui, S.; Musitu, G. Psychological Adjustment in Bullies and Victims of School Violence. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2009, 24, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Continente, X.; Pérez-Giménez, A.; Espelt, A.; Nebot-Adell, M. Bullying among Schoolchildren: Differences between Victims and Aggressors. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K. What Children Tell Us about Bullying in Schools. Child. Aust. 1997, 22, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K. Consequences of Bullying in Schools. Can. J. Psychiatry 2003, 48, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R. Multiple Victimization (Bullying and Cyberbullying) in Primary Education in Spain from a Gender Perspective. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 9, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslea, M.; Rees, J. At What Age are Children Most Likely to be Bullied at School? Aggr. Behav. 2001, 27, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, F.; Aguinaga, C.; Luje, R. Detection of Behavior Ptterns through Social Networks like Twitter, using Data Mining techniques as a method on detect Cyberbullying. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Software Process Improvement (CIMPS), Guadalajara, Mexico, 17–19 October 2018; pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Morata, A.; Alonso-Fernández, C.; Freire, M.; Martínez-Ortiz, I.; Fernández-Manjón, B. Creating Awareness on Bullying and Cyberbullying among Young People: Validating the Effectiveness and Design of the Serious Game. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 60, 101568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Morata, A.; Rotaru, D.C.; Alonso-Fernández, C.; Freire, M.; Martínez-Ortiz, I.; Fernández-Manjón, B. Validation of a Cyberbullying Serious Game Using Game Analytics. IEEE Transact. Learn. Technol. 2020, 13, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomera, R.; Fernández-Rouco, N.; Briones, E.; González-Yubero, S. Adolescents Bystanders´Responses and the Influence of Social Values on Applying Bullying and Cyberbullying Strategies. J. Sch. Violence 2021, 20, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, L.; Segales-Kirzner, M. Study on Social Entrepreneurship in Castile and Leon; Cives Mundi, European Regional Development Fund: Soria, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://projects2014-2020.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/tx_tevprojects/library/file_1506594453.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Piñuel, I.; Oñate, A. AVE Acoso y Violencia Escolar; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Forero, R.; McLellan, L.; Rissel, C.; Bauman, A. Bullying Behaviour and Psychosocial Health among School Students in New South Wales, Australia: Cross Sectional Survey. BMJ 1999, 319, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aggressions | Threats | Blocking | Coercions | Exclusion | Harassment | Intimidation | Manipulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressions | 1 | 0.2059 | 0.4780 | 0.5862 | 0.1515 | 0.0021 * | 0.0196 * | 0.7954 |

| Threats | 1 | 0.1997 | 0.2059 | 0.0641 | 0.0439 * | 0.1598 | 0.1598 | |

| Blocking | 1 | 0.8130 | 0.1883 | 0.3917 | 0.0466 * | 0.0466 * | ||

| Coercions | 1 | 0.6326 | 0.4780 | 0.4367 | 0.0695 | |||

| Exclusion | 1 | 0.2391 | 0.3237 | 0.3237 | ||||

| Harassment | 1 | 0.0119 * | 0.1063 | |||||

| Intimidation | 1 | 0.0530 | ||||||

| Manipulation | 1 |

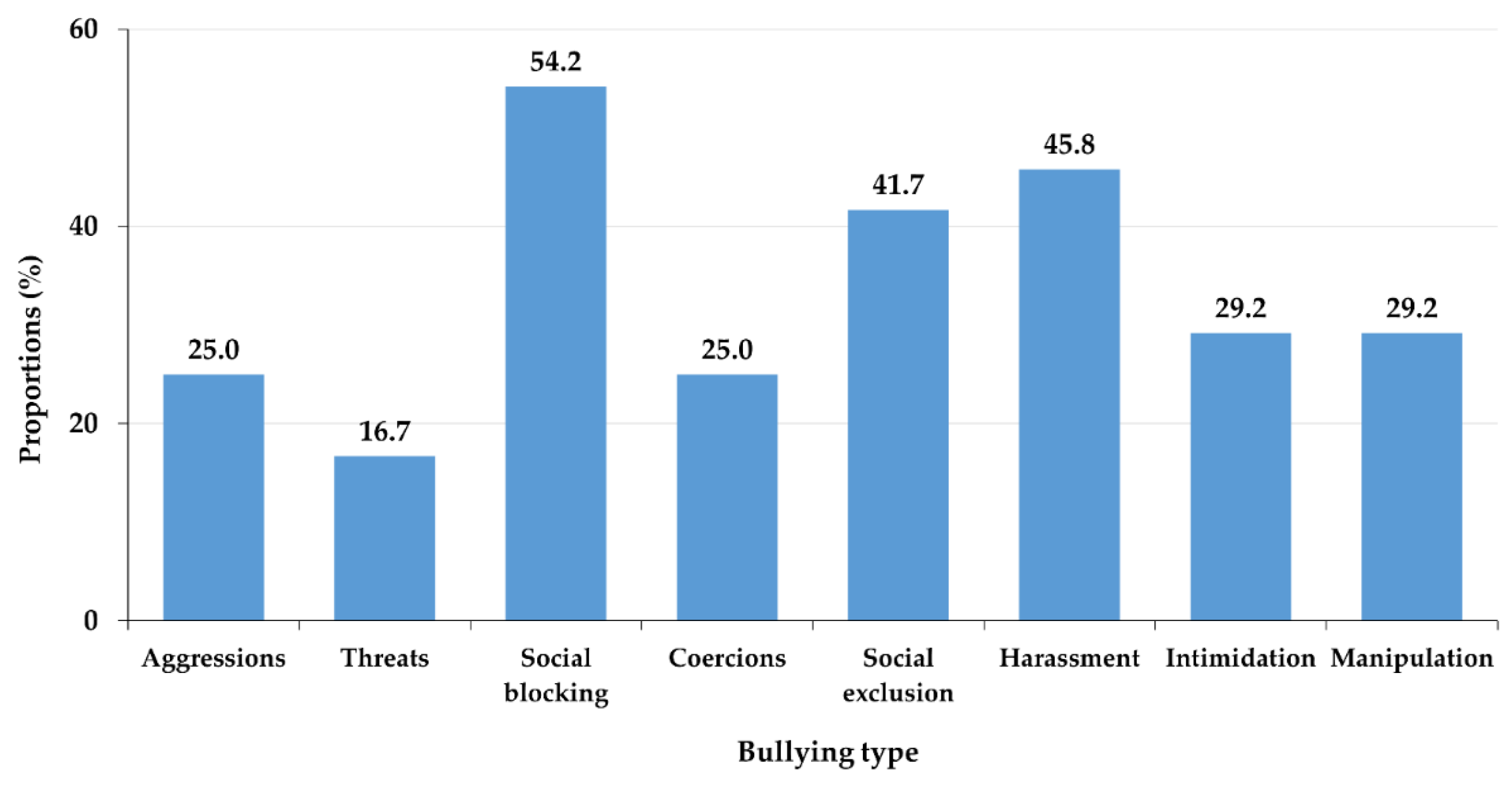

| Bullying Type | Total (%) | Females (%) | Males (%) | Chi-Square | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressions | 25.0 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 1.48 | 0.2235 |

| Threats | 16.7 | 75.0 | 25.0 | 0.32 | 0.5716 |

| Social blocking | 54.2 | 53.8 | 46.2 | 0.91 | 0.3411 |

| Coercions | 25.0 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 2.90 | 0.0883 |

| Social exclusion | 41.7 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 0.41 | 0.5212 |

| Harassment | 45.8 | 72.7 | 27.3 | 0.91 | 0.3411 |

| Intimidation | 29.2 | 71.4 | 28.6 | 0.34 | 0.5621 |

| Manipulation | 29.2 | 85.7 | 14.3 | 2.27 | 0.1317 |

| Mean | Std. Deviation | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 11.61 | 1.80 | 4.00 |

| Bullied | 11.08 | 1.89 | 4.00 |

| Not bullied | 11.69 | 1.77 | 3.00 |

| At risk of being bullied | 12.29 | 1.80 | 1.00 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullied—Not bullied | −0.6105 | 0.4089 | −1.4930 | 0.2850 |

| Bullied—At risk | −1.2024 | 0.7712 | −1.5590 | 0.2560 |

| At risk—Not bullied | 0.5918 | 0.7029 | 0.8430 | 0.6660 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nieto-Sobrino, M.; Díaz, D.; García-Mateos, M.; Antón-Sancho, Á.; Vergara, D. Incidence of Bullying in Sparsely Populated Regions: An Exploratory Study in Ávila and Zamora (Spain). Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020174

Nieto-Sobrino M, Díaz D, García-Mateos M, Antón-Sancho Á, Vergara D. Incidence of Bullying in Sparsely Populated Regions: An Exploratory Study in Ávila and Zamora (Spain). Education Sciences. 2023; 13(2):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020174

Chicago/Turabian StyleNieto-Sobrino, María, David Díaz, Montfragüe García-Mateos, Álvaro Antón-Sancho, and Diego Vergara. 2023. "Incidence of Bullying in Sparsely Populated Regions: An Exploratory Study in Ávila and Zamora (Spain)" Education Sciences 13, no. 2: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020174

APA StyleNieto-Sobrino, M., Díaz, D., García-Mateos, M., Antón-Sancho, Á., & Vergara, D. (2023). Incidence of Bullying in Sparsely Populated Regions: An Exploratory Study in Ávila and Zamora (Spain). Education Sciences, 13(2), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020174