Abstract

Background: Flipped learning (FL) is being considered, in terms of new educational trends, a beneficial pedagogical model in the classroom. In particular, FL and intrinsic motivation (IM) are key components to the model since they can be crucial to a high-quality education. FL for the development of IM in higher education, as well as searches for potential interventions have, thus improved over the past ten years. However, no reviews that analyze the findings and conclusions reached have been published. Consequently, the objectives of this paper were to analyze the relationship between the use of FL and the IM of students in higher education, and to identify the aspects that should be present in FL models to develop the IM that contributes to high-quality education. Methods: in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, a systematic review of PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and ProQuest was carried out. Results: Of the 407 studies that were initially discovered, 17 underwent a full examination in which all findings and conclusions were analyzed. After implementation, the majority of the FL interventions improved IM results. Conclusion: many key aspects have been identified that must be followed in order to intrinsically motivate students using the FL methodology.

1. Introduction

According to the fourth Sustainable Development Goal of the 2030 Agenda [1], high-quality education promotes sustainable development. In this regard, intrinsic motivation (IM) is crucial to promoting high-quality education because students thus find the work itself engaging and fulfilling [2,3,4]. This enables them to give their work meaning, investigate new subjects, meet learning challenges, and create their own objectives or study subjects that pique their curiosity. Furthermore, there is a significant correlation between IM and academic performance and wellbeing [5].

Specifically, IM is the desire to perform a particular task or action in the hopes of finding enjoyment or delight in doing so [6,7,8,9]. The primary focus of self-determination theory (SDT) is on intrinsic motivators that support the basic psychological needs for growth [10,11,12,13,14]: autonomy (the desire for autonomy and a sense of responsibility for one’s actions), competence (where people feel effective and capable), and relatedness (where people feel significantly connected to or cared for by other people and groups). In addition, SDT-based research that particularly aims to promote IM through interventions has emerged recently [15,16,17,18,19]. The value of developing motivation in high-quality education has been examined by the scientific community [16,20,21,22]. As a result, multiple investigations have suggested particular strategies, pedagogical models, or programs to boost motivation in various educational areas and stages, as with, for example, Flipped Learning (FL) [23,24,25,26].

In particular, FL can be defined as a pedagogical model that allows for the relating of aspects of face-to-face education with virtuality, and enables students to be directed to access data in real time without them needing to be present in the classroom, so that the student assumes a fundamental role during the training process, increasing their responsibility, involvement, commitment, and accomplishment [1,7]. In the FL model, homework is completed outside of class while instruction is conducted in class. It is a teaching model where students watch asynchronous instructional videos or read some texts, articles, or books as homework while discussions, projects, experiments, and personalized coaching is carried out during class [3]. Other research highlights that FL has at least three essential elements: students obtain the majority of their course material from outside of the classroom; students actively engage with the material, other students, and the teacher in the classroom to complete higher-order learning activities; and students are required to complete outside-of-class tasks in order to benefit from the in-class activities [8].

At present, there are several studies that have analyzed the positive impact of FL as a pedagogical model to promote an autonomy-supportive learning environment, self-regulation, interaction between students and between students and the teacher, and a deeper engagement with the material, so that it can provide more complete learning experiences [15,16,27]. Additionally, there is an increasing amount of research that emphasizes the importance of FL for optimal academic performance [17,18,19]. FL enables students to be prepared for higher-order academic activities such as problem-solving [27]; it leads to better final examination scores, performances, and overall success [16]; and it has advantages in terms of time optimization, active learning, and understanding [10]. Therefore, FL is a very helpful pedagogical model because the outcomes of its use are the development of the competencies required by different educational programs.

Finally, the importance of IM to achieve high-quality learning in higher education has also been the focus of numerous FL investigations based on SDT [10,11,12,13]. The scientific community attaches great importance to this topic, so it is useful to be able to compile the knowledge that is currently available on different FL pedagogical models that promote IM. As a consequence, it will be possible to compile up-to-date data on the many types of interventions being employed and draw illuminating conclusions for subsequent research. The demand for collection and analysis, with the aim of closely evaluating the importance of IM in FL, served as the initial impetus for the current study. Therefore, this systematic review had two research questions: (1) ‘What is the relationship between the use of FL and IM in higher education like?’ and (2) ‘What aspects should be present in the FL model to develop IM?’. Therefore, the objectives of the present review are the following: (1) ‘to analyze the relationship between the use of FL and the IM of students in higher education’ and (2) ‘to identify the aspects that should be present in FL models to develop IM that contribute to quality education’. As a result, it will be possible to gather up-to-date information on the many types of interventions being used and make insightful reflections for future research. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, although some studies have summarized FL for education [28,29,30], a systematic review that includes FL for the development of IM in higher education has not yet been published. This study will be especially useful for academics, researchers, and instructors looking for high-quality education that complies with the 4th SDG of the 2030 Agenda.

2. Materials and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed when conducting this systematic review [5,14] (Supplementary Material S1). The PRISMA-supported standards guarantee that each of the listed articles has undergone a careful review process.

2.1. Design

To identify articles published before 23 July 2023, a systematic search was conducted of the Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest databases. The search was conducted on titles, abstracts, and keywords, and the search strategy included words relating to (1) population, (2) interventions, (3) and outcomes. The three groups of keywords were combined using AND, and the terms in each group were linked using OR: population—“university”, “higher education”, “high education”; intervention—“flipped classroom”, “flipped learning”; and outcomes—“intrinsic motivation”, “self-determination theory”.

2.2. Screening Strategy and Selection of Scientific Articles

Duplicate records were deleted when the search was ended. The remaining records were then checked to see if they met the inclusion or exclusion criteria, which are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

2.3. Data Selection

The aspects of FL pedagogical models that could foster IM as well as data that can most correctly represent FL have been extracted. To achieve this, the information collected from the original publications is presented in three tables: The first presents the aim of the study, the country, sample, area, measurement methods, results, and conclusions. The second one details the year of studies, the duration of FL, whether it was gamified or not, and the detailed intervention. The third table shows the aspects that should be present in the FL model depending on the moment in time and the person responsible for its execution.

2.4. Methodological Assessment

By adapting the STROBE evaluation criteria, the methodological evaluation process was applied to find articles that were appropriate for inclusion [20]. Each item was scored using a numerical description (1 = finished, 0 = not finished). Following O’Reilly et al. [5], each study’s rating was qualitatively examined in accordance with the rules detailed in the Supplementary Material S2. Articles with scores below seven were considered to be at a high risk of bias, while those with scores over seven were considered to be at low risk.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Selection of Studies

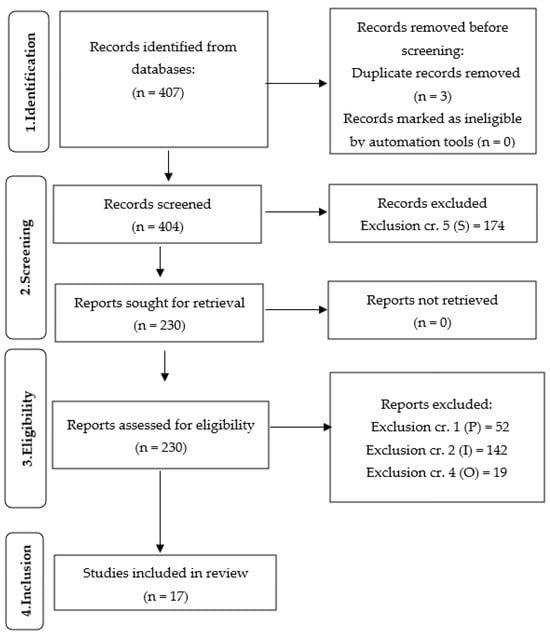

A total of 407 documents, of which 3 were duplicates, were initially obtained from the Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest databases. As a result, 404 articles in total were downloaded. Following a second review of the remaining publications’ titles, abstracts, and complete texts, using the same criteria described in Table 1, 174 studies were disregarded in accordance with Criterion 5 (Study). Of the remaining 230 articles, 52 were removed for not meeting Criterion 1 (Population), 142 were removed based on Criterion 2 (Intervention), and 19 were removed for not meeting Criterion 4 (Outcomes). Finally, 17 articles were included in the qualitative analysis. The four PRISMA-recommended phases are depicted in a flow diagram in Figure 1, along with the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each article in each phase.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

3.2. Methodological Quality

Table 2 shows that the overall methodological quality of the articles is very high based on our assessment using each of the STROBE evaluation criteria [5], which have been described in Section 2.4.

Table 2.

The methodological quality of the articles.

3.3. Article Analysis

Below are the outcomes from the analysis of the studies, together with the most crucial information regarding the FL developed in each study. To achieve this, the information collected from the original publications is presented in three tables: Table 3 details the specific information on each FL intervention. Table 4 provides the aspects that should be present in the FL model depending on the moment in time and the person responsible for its execution. Table 5 presents the primary information on each study (aim, country, sample, area, measurement methods, results, and conclusions).

Table 3.

Description of FL interventions.

Table 4.

FL model depending on the moment in time and the person responsible.

Table 5.

The studies’ country, sample, area, measurement methods, results, and conclusions.

Table 3 shows that the academic year in which FL has been applied is very varied, thus, it is not necessary to have a higher or lower level of knowledge of a subject. As for the duration of the interventions, they are very varied, from a couple of weeks to a semester or two whole semesters. Likewise, it can be observed that the interventions were either gamified or not.

Additionally, as shown in Table 4, instructors provide different types of materials to students to prepare the subject matter prior to face-to-face classes: lectures, textbooks, gamified e-books, audios, videos, case studies, publications about the subject, contact information for experts, and other e-resources. The materials must be accessible; attractive, so that they arouse the curiosity of the students; well organized; and include the most relevant and up-to-date information, and all this in accordance with the objectives of the subject and the course. In order to make the material available to the students, the instructors use different systems: printed documents, email, WhatsApp, Facebook, Youtube, Moodle, Google Classroom, Blackboard, ECHO360 software, and the Socrative platform. In relation to the research results, it can be seen in Table 5 that the majority of the studies found that IM had been developed following the FL pedagogical model and relied on the SDT, which supports the basic psychological needs required for the growth of autonomy, competence, and relatedness [10,11,12,13,21,22,24,25,26,31,32,35,36]. In addition, some studies that have compared traditional FL and gamified FL have found better results with the later, since it encouraged students to participate in the learning process [23,37], while another study that did so perceived improvements only in IM and social relatedness [34]. Finally, one study found no significant differences in IM between students who followed FL and those who received traditional instruction [33]. However, the authors of this study believe that although their intervention had the potential to increase IM, it may have been too short to have had an effect.

As can be seen in Table 5, the studies analyzed are student-driven, because the articles focus on the impact of FL on student motivation, and its other benefits for students, to achieve quality education. Additionally, the study topic is interesting independently of cultural or educational approaches since most of the sampled studies are numerous, representative, and geographically spread across a wide range of regions. A variety of tools are used for measuring, such as standardized scales, interviews, ad hoc surveys, and observation. Because of this, extensive findings from many perspectives can be obtained.

With regard to the conclusions of these studies, it can be observed in Table 5 that FL is a pedagogical model that assists in the development of IM, and specifically of the three basic psychological needs for it [9,10,28,29,30,35,37,38,39,40,41]. The discussion in this article analyzes the causes of the development of IM. Research has highlighted five different aspects that have been taken into account, such as the redesign of the course content [10], as the teacher must be conscious of the need to reinforce preparation for in-class work [31]; instructor support [12], since it favors students´ relatedness (see Table 4); the interactive nature of the learning environment that allows flexibility in time and place, and interaction with a variety of learning sources such teachers and peers [11,12,21]; the importance of varied materials like watching video lectures or talks, reading text-based material, and taking online quizzes [25,32,35,36,37]; and, finally, it is worth mentioning the importance of well-designed gamification used in conjunction with the FL model to encourage students to participate in the learning process and improve their learning perception [23,24,34,37].

4. Discussion

This study has answered the following research questions: (1) ‘What is the relationship between the use of FL and IM in higher education like?’ and (2) ‘What aspects should be present in the FL model to develop IM?’.

Regarding the first research question, this systematic review has shown that the published interventions employing FL as a pedagogical model have helped to increase IM. In relation to autonomy, the participants of the analyzed articles were motivated to study and practice the tasks, were able to learn on their own, took responsibility for their education, made decisions, and had the necessary confidence in their ability to learn. In addition, students had plenty of opportunity for self-learning in a welcoming and non-threatening learning environment due to the FL intervention [21]. Furthermore, the students had the freedom to choose the time and location of their own education as well as to start studying assignments on their own. In relation to competence, the SDT states that meeting students’ desire for competence explains why pre-class materials are successful. Pupils thought that there was no difficulty in learning from the resources (need for competence). Students had a sense of control over their learning outcomes and competence with tasks and activities. Pupils admitted that they felt comfortable speaking up during class discussions and that they arrived to class prepared. In relation to relatedness, some studies concluded that the FL classroom layout was incredibly inspiring and stimulating for group discussions, ensuring a cordial and cooperative exchange of ideas, which is consistent with other research [39,40]. Additionally, students can gain quick scaffolding from other students through this cooperation and group interaction, which helps them overcome numerous learning obstacles and complete the assignments to the required standards. The students thought that their experience in FL had taught them something new, they could share knowledge with their teacher and peers on an equal platform, helping them grow as critical thinkers and problem solvers, which was consistent with other research [41,42].

Regarding the second research question, this review has identified several aspects that help to promote IM in FL interventions. It is important to have a good knowledge of the FL guidelines before designing the objectives and methodologies of a subject, taking into account the coordinators of the FL implementation. For this purpose, it is strongly advised that teachers take advantage of training seminars in order to understand how to use FL to organize their course instructional activities. A symbiosis is therefore required between in-depth knowledge of the FL and technical competency of the subject. This is congruent with other studies [43,44]. It is also advisable that the instructor has support to prepare their videos or material, for example, or for any questions that may arise during the FL teaching.

Another aspect to FL is to convey the significance of this pedagogical method to the students so that they are aware of what FL is before they begin the course. It is also necessary for students to become acquainted with this method in order to take an active and accountable role in their education. When the program educational goals were determined, the students were informed about the working technique from the very beginning [45], and their acceptance of it could be depended upon. Employing the FL methodology improved the educational experience for pupils and promoted favorable learning results and behavioral adjustments. By using a graded method, cognitive overload was avoided and students were given control over their learning process. In this respect, to feel in control in such a novel environment, students who have not previously utilized FL may require more than an introductory lecture and a course description in the curriculum.

It is also important to assess the difficulties that students have in implementing FL [12]. Some students find this approach too harsh at first, and they require support and inspiration to adjust to a new, more engaging approach to learning [46]. Given the difficulty of designing a FL course to support first-year student motivation, it may not be advisable to use FL for an introductory course [12,47]. As the novelty of this instructional strategy wore off, students’ favorable attitudes toward the flipped approach waned throughout the course [48]. In this regard, some students believe that the increased demand for independent study outside of class time and the absence of lectures are unfair or excessive [49]. It is crucial for learners and trainers to communicate continuously throughout the process in order to overcome these challenges. One strategy suggested for students is to write their thoughts about the use of FL in a journal. After that, teachers talk with students about their reflections to find out what challenges they are facing and how to overcome them [12].

Another important aspect of FL is to make sure that the material has been prepared before going to class. In order to achieve this, it is crucial to let students know ahead of time about the information they need to prepare on their own. It is obvious that students who prepare the necessary materials ahead of time will grasp the information more readily than those who arrive at traditional classrooms with no prior knowledge of the subject matter [10]. Using tools such as quizzes offers teachers a chance to verify the work that the students have completed on their own [23,34].

Another aspect of FL is knowing how to combine student autonomy with interactions between students and expert teachers throughout the intervention [21]. These two facets stem from Vygotsky’s social constructivism theory of learning [50], which holds that students’ autonomous efforts in creating new information and meaning through social interaction and teamwork constitute learning. Programming milestones offer intentional practice opportunities spaced throughout the semester that impact learning and promote autonomy. Rather than assigning students a set of tasks to complete in a predetermined order, this feature lets them design their own plan to meet the course requirements and choose the next challenge to solve [35]. Regarding interaction, learning occurs when someone tries to explain to others what he or she knows about the task. Students might gain a deeper understanding of their viewpoints through the discussion [37]. They can gain greater confidence to complete the tasks in this way. When faced with challenges, people can return to the learning content in the material to find the information required to do the activity, and, because of the material’s useful feedback, they feel more capable. Teachers should also give pupils the right resources and feedback to help them feel successful and self-sufficient. For instance, rather than evaluating pupils based on norms, more pertinent information may be provided to help them grasp how to complete the learning tasks [37].

Another significant aspect of FL is that using gamification in a FL intervention gives students a lot of chances for engagement and fun [24,35,37]. It is now simpler for pupils to take pre-class material seriously due to the gamification of quizzes. This is why the questions chosen and the gamified quiz design are so important, as the level of difficulty of the test might affect students’ motivation. The team leaderboard-based intervention, the use of badges, and the instant task-level feedback that games offer in the form of points can enhance the effectiveness of the learning process [23,34]. In addition to the feedback mechanisms that are employed, social interaction formats must also be taken into account. Implementing team competition is another crucial step in ensuring a positive culture of competition. Students’ social relatedness was effectively fostered by this kind of contact. This could be the case because, among other things, it facilitates enriching discussions and exchanges and aids in encouraging student feedback and involvement. Similarly, the use of technology to access educational resources increased students’ autonomy and engaged them in the process of finding and analyzing knowledge [10].

Other aspects that should be taken into account, but that are not specific to FL and are applicable to almost any learning process, are that the content should be well-designed, teacher support should be promoted, or a variety of rich materials should be offered.

In general, this systematic review has identified that IM can be promoted by FL as autonomy, competence, and relatedness are promoted in the participants of the analyzed articles through the encouragement of different aspects of FL intervention. In this regard, it is crucial to keep in mind that FL pedagogical models used to support IM must achieve the following strategies:

- -

- have a good knowledge of the FL guidelines before designing the intervention.

- -

- explain adequately to the students what FL is all about.

- -

- monitor the students’ difficulties with regard to the FL intervention.

- -

- make sure that students have prepared the material before class.

- -

- know how to combine self-study with interaction.

- -

- use badges and leaderboards in the gamification used in the FL intervention.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the inclusion of the most pertinent databases, it is conceivable that some additional publications might be located in other databases, which could be a limitation of the current study. In addition, it is also possible that some articles could be discovered in other languages, because articles that have not been published in English or Spanish have been excluded from this study. Additionally, it should be mentioned that there are several limitations to the research that was analyzed. Because the surveys relied on retrospective and self-assessment comments, certain studies may have had a limited sample size, and a dataset that was only collected once, at a particular school or institution; consequently, some results may potentially be biased due to the subjectivity of the students. Finally, the present review has identified 17 articles; as more articles are published in the future, the results can be further generalized with the addition of new systematic reviews.

This article can act as the starting point for further research, because the scientific community has shown that the development of IM through FL is a very relevant topic that is still developing and has a long way to go. In this regard, as previously discussed, the technology applied in FL is very important for the development of students’ IM. Therefore, new technological advances that can be applied in education, such as artificial intelligence, should be investigated in the future. Finally, due to the diversity of the work being carried out to foster IM through FL, this is an ideal field for innovation in line with the suggestions made in this review.

6. Conclusions

In this systematic review, the two research objectives have been fulfilled: (1) ‘to analyze the relationship between the use of FL and the IM of students in higher education’ and (2) ‘to identify the aspects that should be present in the FL model to develop IM that contribute to quality education’. Given that past reviews on FL had different purposes, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no systematic review has examined the two research objectives of this paper. As a result, this review’s most pertinent theoretical contributions address the objectives that are outlined below.

Regarding the first research objective, it may be said that the results of the analyzed articles suggest that applying the FL methodology increases students´ IM. Following the SDT, this approach promotes the three elements of students´ basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence, and relatedness). Due to the benefits of implementing a FL methodology, this approach is becoming more common in universities across a range of academic and geographic areas.

Regarding the second research objective, it should be noted that all studies concurred on the need to recommend specific aspects of FL, based on the development of IM through FL, because doing so motivates students to be more interested in their studies and provides them with a sense of accomplishment. In this review, in the discussion, six key aspects have been identified that must be followed in order to intrinsically motivate students using the FL methodology.

This study also supplies practical implications for lecturers, teachers, or instructors that they can use as a guide in their classes. Therefore, practical aspects are provided on how to motivate learners intrinsically in an FL intervention. While there is not a single script that works for all FL interventions, students find that being prepared before class helps them concentrate on solving issues and participating actively. While a FL intervention might not be appropriate in every educational setting, it might be when it best meets the needs of the teacher, the students, and aligns with the subject matter.

The implementation of FL that supports IM is required to guarantee high-quality education. As a result of the aforementioned initiatives, the fourth Sustainable Development Goal of the 2030 Agenda can be supported. This goal emphasizes the need to give all students access to high-quality education and encourage possibilities for lifelong learning [1].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci13121226/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Supplementary S2: Standards for Assessing the Quality of Articles. Reference [51] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K.A. and A.V.; methodology, R.K.A. and M.R.-G.; formal analysis, R.K.A., M.C.M.-M. and M.R.-G.; investigation, A.V.; data curation, R.K.A., M.C.M.-M. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.A. and A.V.; writing—review and editing, A.V., M.C.M.-M. and M.R.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Giangrande, N.; White, R.M.; East, M.; Jackson, R.; Clarke, T.; Saloff Coste, M.; Penha-Lopes, G. A Competency Framework to Assess and Activate Education for Sustainable Development: Addressing the UN Sustainable Development Goals 4.7 Challenge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lio, A.; Dhaliwal, H.; Andrei, S.; Balakrishnan, S.; Nagani, U.; Samadder, S. Psychological Interventions of Virtual Gamification within Academic Intrinsic Motivation: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotos-Martínez, V.J.; Tortosa-Martínez, J.; Baena-Morales, S.; Ferriz-Valero, A. Boosting Student’s Motivation through Gamification in Physical Education. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Frías, E.; Arquero, J.L.; Del Barrio-García, S. Exploring How Student Motivation Relates to Acceptance and Participation in MOOCs. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Caulfield, B.; Ward, T.; Johnston, W.; Doherty, C. Wearable Inertial Sensor Systems for Lower Limb Exercise Detection and Evaluation: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1221–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q. Information Literacy and Recent Graduates: Motivation, Self-Efficacy, and Perception of Credit-Based Information Literacy Courses. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2023, 49, 102682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beluce, A.C.; Oliveira, K.L.D. Students’ Motivation for Learning in Virtual Learning Environments. Paidéia 2015, 25, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holding, A.; Koestner, R. A.; Koestner, R. A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on How to Choose, Use, and Lose Personal Goals. In The Oxford Handbook of Educational Psychology; O’Donnell, A., Barnes, N.C., Reeve, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-0-19-984133-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bochiş, L.N.; Barth, K.M.; Florescu, M.C. Psychological Variables Explaining the Students’ Self-Perceived Well-Being in University, During the Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 812539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawaneh, A.K.; Moumene, A.B.H. Flipping the Classroom for Optimizing Undergraduate Students’ Motivation and Understanding of Medical Physics Concepts. EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2020, 16, em1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Perera, C.J. Exploring Students’ Competence, Autonomy and Relatedness in the Flipped Classroom Pedagogical Model. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velde, R.V.D.; Van Westrhenen, N.B.; Labrie, N.H.M.; Zweekhorst, M.B.M. ‘The Idea Is Nice… but Not for Me’: First-Year Students’ Readiness for Large-Scale ‘Flipped Lectures’—What (de)Motivates Them? High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.S.; O’Reilly, J.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Zhang, J.H. Evaluating the Flipped Classroom Approach in Asian Higher Education: Perspectives from Students and Teachers. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1638147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, N.S.; Kofoed, L.B.; Bruun-Pedersen, J.R.; Andreasen, L.B. Flipped Learning in a PBL Environment—An Explorative Case Study on Motivation. EJSBS 2020, 27, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-W.; Shen, P.-D.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-H. How to Solve Students’ Problems in a Flipped Classroom: A Quasi-Experimental Approach. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 2017, 16, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Mesa, M.-C.; Castañeda-Vázquez, C.; DelCastillo-Andrés, Ó.; González-Campos, G. Augmented Reality and the Flipped Classroom—A Comparative Analysis of University Student Motivation in Semi-Presence-Based Education Due to COVID-19: A Pilot Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendaña-Cuervo, C.; López-González, E. Impacto de La Clase Invertida En La Percepción, Motivación y Rendimiento Académico de Estudiantes Universitarios. Form. Univ. 2021, 14, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlan Yılmaz, F.G. An Investigation into the Role of Course Satisfaction on Students’ Engagement and Motivation in a Mobile-assisted Learning Management System Flipped Classroom. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2022, 31, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, H.; Lowell, V.; Watson, W.; Watson, S.L. Using Personalized Learning as an Instructional Approach to Motivate Learners in Online Higher Education: Learner Self-Determination and Intrinsic Motivation. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2020, 52, 322–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challob, A.I. The Effect of Flipped Learning on EFL Students’ Writing Performance, Autonomy, and Motivation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 3743–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Carrion, R.; Franco-Leal, N. Antecedents of Academic Performance in Management Studies in a Flipped Learning Setting. J. Educ. Bus. 2022, 97, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzeky, M.E.H.; Elhabashy, H.M.M.; Ali, W.G.M.; Allam, S.M.E. Effect of Gamified Flipped Classroom on Improving Nursing Students’ Skills Competency and Learning Motivation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Carrasco, C.-J.; Monteagudo-Fernández, J.; Moreno-Vera, J.-R.; Sainz-Gómez, M. Effects of a Gamification and Flipped-Classroom Program for Teachers in Training on Motivation and Learning Perception. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, T.; Kurniawan, R.; Zainuddin, Z.; Keumala, C.M. The Role of Pre-Class Asynchronous Online Video Lectures in Flipped-Class Instruction: Identifying Students Perceived Need Satisfaction. J. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamsyah, R.; El Bouazzaoui, A.; Kanjaa, N. Impact of the Flipped Classroom on the Motivation of Undergraduate Students of the Higher Institute of Nursing Professions and Health Techniques of Fez-Morocco. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Zhao, K.; Lee, C.R.; Runshe, D.; Krousgrill, C. Active Learning through Flipped Classroom in Mechanical Engineering: Improving Students’ Perception of Learning and Performance. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2021, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut-Ilgu, A.; Jaramillo Cherrez, N.; Jahren, C.T. A Systematic Review of Research on the Flipped Learning Method in Engineering Education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lui, A.M.; Martinelli, S.M. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Flipped Classrooms in Medical Education. Med. Educ. 2017, 51, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, M. A Systematic Review of the Use of Gamification in Flipped Learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 3327–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, J.; Sturges, D.; Schlote, R. Flipping the Classroom: Effects on Course Experience, Academic Motivation, and Performance in an Undergraduate Exercise Science Research Methods Course. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2018, 18, 22729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzer, N.; Krishna, B.; Kotangale, A.; Mohandas, L. HyFlex Environment: Addressing Students’ Basic Psychological Needs. Learn. Env. Res. 2023, 26, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll-Khosrawi, P.; Zöllner, C.; Cencin, N.; Schulte-Uentrop, L. Flipped Learning Enhances Non-Technical Skill Performance in Simulation-Based Education: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, M.; Sailer, M. Gamification of In-class Activities in Flipped Classroom Lectures. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenberg, P.; Navon, J.; Nussbaum, M.; Pérez-Sanagustín, M.; Caballero, D. Learning Experience Assessment of Flipped Courses. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2018, 30, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng Flipping the Classroom and Tertiary Level EFL Students’ Academic Performance and Satisfaction. J. Asia TEFL 2017, 14, 605–620. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Hwang, G.-J.; Chang, S.-C.; Yang, Q.; Nokkaew, A. Effects of Gamified Interactive E-Books on Students’ Flipped Learning Performance, Motivation, and Meta-Cognition Tendency in a Mathematics Course. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 3255–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, L.; Hayes, J.R. A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. Coll. Compos. Commun. 1981, 32, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bahrani, R.H. Flipped Classroom as a New Promoting Class Management Technique. J. Fac. Educ. 2020, 2, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.Y.; Hussin, S.; Ismail, K. Implementation of Flipped Classroom Model and Its Effectiveness on English Speaking Performance. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2019, 14, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enfield, J. Looking at the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Model of Instruction on Undergraduate Multimedia Students at CSUN. TechTrends 2013, 57, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Attaran, M. Malaysian Students’ Perceptions of Flipped Classroom: A Case Study. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2016, 53, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urfa, M. Flipped Classroom Model and Practical Suggestions. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 2018, 1, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang, K.; Ollermann, F. Flipped Classroom Evaluation Using the Teaching Analysis Poll. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’19), Valencia, Spain, 25–28 June 2019; Universitat Politècnica València: Valencia, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gilboy, M.B.; Heinerichs, S.; Pazzaglia, G. Enhancing Student Engagement Using the Flipped Classroom. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraut, G.L. Inverting an Introductory Statistics Classroom. Primus 2015, 25, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, J.F. How Learning in an Inverted Classroom Influences Cooperation, Innovation and Task Orientation. Learn. Env. Res. 2012, 15, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, S.; Beal, M.; Lamb, C.; Sonderegger, D.; Baumgartel, D. Flipping Undergraduate Finite Mathematics: Findings and Implications. Primus 2015, 25, 814–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.G. The Flipped Class: A Method to Address the Challenges of an Undergraduate Statistics Course. Teach. Psychol. 2013, 40, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S.; Cole, M. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).