Abstract

This article explores Finnish early childhood education student teachers’ mental images of the concept of the environment. The empirical dataset consists of drawings made by the student teachers (n = 106) and their written reflections (n = 40). A qualitative content analysis was performed on the drawings, utilizing the concepts of geography. Consequently, the elements of the natural environment, the built environment, public space, and private space in the drawings were explored. The results show that over half of the drawings do not depict any elements of the built environment, which is why these drawings depict the concept of nature rather than that of the environment. In everyday language, ‘nature’ is often regarded as a synonym for the ‘environment’. In addition, more than 80% of the drawings lacked people. The natural environment, instead, was depicted as ideal without any environmental problems. The results suggest that the student teachers do not associate people and the built environment with the concept of the environment, culminating in a lack of interaction between people and the environment. Therefore, the study recommends diversifying student teachers’ perceptions of the environment. Future teachers who have a better conceptual understanding of the environment are more likely to provide children with increased opportunities for exploring and investigating both the natural environment and the built environment.

1. Introduction

The ‘environment’ is one of the key concepts in geography, but because of the various ways the term is used in everyday language, in different disciplines, and also in geography, its essence is often lost [1]. For instance, in everyday language, the environment often means the same as nature [2,3,4]. Many other geographical concepts, such as place and landscape, are close to the words used in everyday language as well, which is why their geographical meaning can be unclear [5].

Nonetheless, it is important to understand that the concept of the environment includes both the built environment and the natural environment, whereas the concept of nature mainly refers to the latter. For instance, according to the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care [6], pedagogical activities should take place in both the built and natural environments. Therefore, it is relevant to investigate how diverse Finnish early childhood education student teachers’ mental images of the environment are.

Traditionally, the immediate environment that surrounds children and young people has been considered a natural starting point for geography education [1]. Not only do most people in the world live in cities, but the built environment also mirrors the values and social situation of its time and possesses inherent esthetic worth [7].

This article focuses on the concept of the environment, especially from the point of view of the built environment and humans as part of the environment. The empirical dataset of this article consists of drawings made by Finnish early childhood education student teachers (n = 106) and their written reflections (n = 40). The instruction was to draw the environment as it is typically presented for children, among others, in children’s literature. The research questions of this article are as follows:

- What does the environment–human relation look like in the student teachers’ drawings?

- What sorts of implications do the student teachers’ mental images of the environment have on geography and environmental education?

Next, the key concepts of this study are introduced, many of which are geographical ones. First, the concepts of nature and the environment are presented in order to illustrate how they differ from each other. Second, the concept of landscape is explained as it compasses both the natural and built environments. Moreover, the term ‘landscape’ quite often appears as part of the instruction given to participants in environmental studies that involve drawing as a research method. Third, public space and private space are described because they are used in the analysis of the student teachers’ environmental drawings (see Section 3.2). Fourth, the results of a few exemplary works of research on environmental drawings are summarized at the end of Section 2.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Nature

Nature and the environment are central concepts of both environmental education and geography education [2,3,4]. Sue Elliot [8] has presented four approaches to defining nature. In the first approach, nature is thought of as wild, untouched by humans, and a distant destination for adventures. In the second approach, everything other than what is human-made and manufactured is understood as nature. Advertising takes advantage of the second approach as products are often described as natural or organic, as if they were directly from nature, although they are not [3]. The third approach comes from economics and natural sciences, where nature is seen as a source of natural resources and materials, as well as the object of research and classification. In the fourth approach, nature is understood as a holistic system made by ecosystems, where all parts influence each other and are dependent on each other.

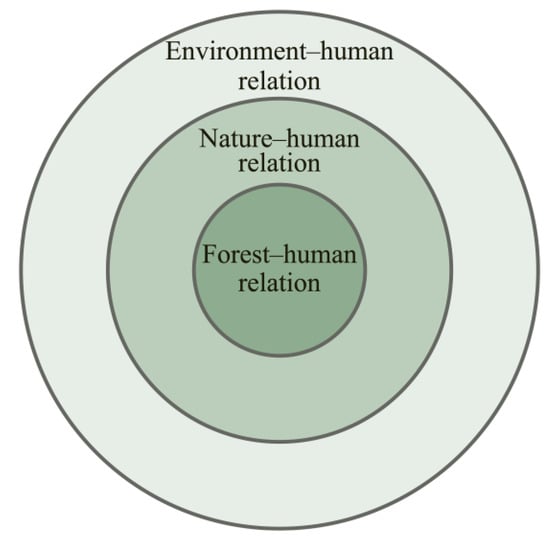

Although the concept of nature is ambiguous and difficult to define [9], Risto Wil-lamo [10] highlights that it is important to understand humans as part of nature. Humans cannot live without oxygen or food produced by the plants. Thus, nature is in people themselves: in the materials of the body, in the air people breathe, in the food people eat, and in the materials of the built environment. Figure 1 presents the relations between humans and the forest, nature, and the environment. The forest–human relation expands into a relation with nature when, in addition to the forest, people have experiences with other elements of nature, such as lakes or mountains. On the other hand, forest and nature are often considered synonyms. In turn, the nature–human relation expands into an environmental relation when elements of the built environment come into the picture. The city, that is, the built environment, is often considered the opposite of nature [11]. However, instead of dichotomous thinking, natural environments and built environments should be seen as opportunities to organize early childhood education and geography education in diverse learning environments [6,12].

Figure 1.

Human relations with the forest, nature, and the environment, adapted and modified from [13] (p. 6).

2.2. Environment

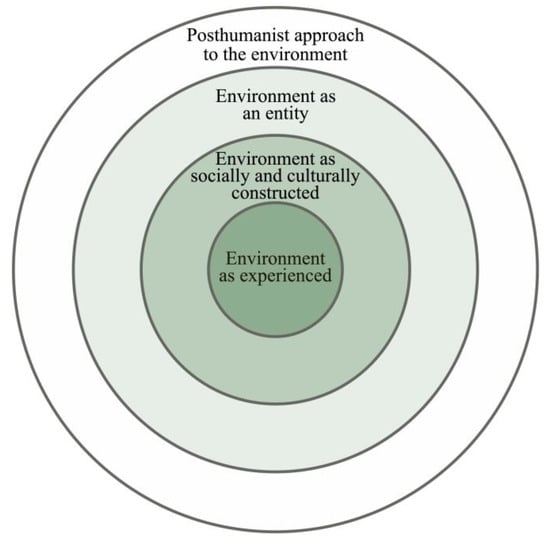

In addition to the concept of nature, the environment can also be defined in many ways. Sirpa Tani [1] has presented four approaches to defining the environment. The first approach is called the ‘environment as an entity’. In natural sciences, the environment is often treated as something that is detached from the observer. The environment and environmental problems are understood as an entity located outside of humans, which is viewed objectively from a distance. According to this approach, humans observe and study the environment from a distance without influencing it in any manner.

The second approach is called the ‘environment as experienced’ [1]. The environment is understood as always subjective and unique, defined by the person who explores it. Subjective experiences, a sense of place, esthetic values, and sensory observations of the environment are typical features of this approach. The environment is, therefore, not an object of research but an experienced and lived entity. In the end, the immediate environment becomes a personal and meaningful place. The individual-centered understanding of the environment has been common in environmental education. It has been used to emphasize the importance of personal relationships with the environment, which already begin to form in early childhood. The impact of childhood environmental experiences on an individual’s later environmental attitudes is emphasized, for instance, in Palmer’s [14] tree model. According to it, children should be able to spend time in outdoor environments playing and exploring, learning topics that interest them about the environment, such as the seasons and the hydrological cycle, and act for the good of the environment, for instance, by sorting and recycling waste [3].

The third approach is called the ‘environment as socially and culturally constructed’ [1]. This approach highlights the social elements of the environment, political decision-making related to the environment, and the impact of various environmental problems on human activity. Therefore, the third approach is typical of environmental policy and environmental protection. It combines scientific observations with personal value-laid experiences. In doing so, conflicts of opinion may arise between different groups of people [15].

In addition to the three above-mentioned approaches to the environment, a fourth approach has become more common in recent years, that is, the ‘posthumanist approach’ [4]. This means breaking away from a human-centered way of thinking. Therefore, humans and the environment are not seen as two separate entities; that is, the border between human and non-human is not essential. Instead, the focus is on the mutual emergence of humans and the environment in relation to each other and how they are in constant interaction with each other, creating new ways of being in the world [16].

In summary, all four approaches to the concept of the environment are visualized in Figure 2. An individual can be imagined in the center of Figure 2. The environment–human relation begins to form with the individual’s own experiences and observations in the immediate environment. This relationship expands to the socially and culturally constructed environment when individuals interact with each other, discussing how to use the environment and its affordances. The natural environment and the built environment form the physical entity in which individuals and societies live, communicate, and act on a daily basis. Lastly, the rhizomes [16] that interconnect humans and the environment with each other in the posthumanist approach form the background of Figure 2, creating spaces and opportunities to see and sense the world from new perspectives.

Figure 2.

Four approaches to the concept of the environment.

2.3. Landscape

Although, as described above, the environment can be defined in different ways, most often, the concept of the environment includes both the natural environment and the built environment. These two aspects can also be explored with the geographical concept of the landscape, which quite often refers to what opens in front of or below the viewer [17]. That is, landscape denotes a ‘view’, a ‘prospect’, a ‘vista’, or ‘the object of one’s gaze’ [18] (p. 104). Natural landscapes include, for instance, lakes, ponds, rocks, forests, mountains, and seascapes. The cultural landscape, on the other hand, includes urban and village landscapes, such as shops, city views, apartment buildings, field landscapes, and the built countryside [19]. However, since human influence is noticeable in most landscapes, there is no need for a clear boundary between the site of nature and the site of culture. Thus, nature and the city do not have to be understood as a binary opposition but can be seen as intertwined.

2.4. Public and Private Space

Along with landscape, space is one of the most central concepts in geography. For instance, in the environmental projects implemented at schools, attention can be paid to how the space is experienced by different groups of residents, that is, to the meanings people attach to their environments [4]. In addition, spaces can be thought of as private or public based on their ownership, that is, depending on whether they are privately or publicly owned. However, it might be more fruitful to pay attention to the interaction that takes place between the space and its users and to the means with which this interaction is being regulated [20]. Indeed, although openness is quite often associated with public spaces, they are regulated by rules and norms, the existence of which is often noticed only when someone deviates from them. Therefore, public spaces are in a state of constant change because the users shape them through their own activities [21].

2.5. Exemplary Research on Environmental Drawings

In the Finnish context, Eija Yli-Panula and Varpu Eloranta [22] have studied pupils in basic education (grades 1–2, 5–6, and 8–9) and their relations to the environment. They asked the pupils to draw the landscape they wanted to conserve. The results showed that the natural landscape was the most common one in all three age groups. In the natural landscapes, pupils quite often drew vegetation (e.g., trees, forests, and flowers), elements of water (e.g., lakes, creeks, rivers, and the sea), the sky, and the sun. One-third of the landscapes represented the built environment in which the natural landscape had been more or less affected by human activity. The number of built landscapes did not vary markedly between the three age groups. The third of the main categories, that is, drawings in which human beings were physically present, was the most infrequent and was relatively most often drawn by pupils in grades 5–6.

Another study [23] consisted of drawings made by 11–16-year-old Finnish and Swedish students. The results showed that all three landscape types—that is, the natural, built, and social—were presented in the drawings. The natural and built landscapes were the most frequent types, with the proportion of natural landscapes increasing and that of built landscapes decreasing with age. There were many similarities in the landscapes drawn by the Finnish and Swedish students. For instance, many of the drawings included trees, forests, and elements of water in addition to the elements of the built environment. According to the researchers, boys drew built landscapes more often than girls and Finnish students drew summer cottages, a cultural phenomenon typical of Finnish landscapes, which was not found in Swedish drawings.

The natural environment and the built environment have also been connected with human health and well-being. Eija Yli-Panula, Eila Jeronen, Eila Matikainen, and Christel Persson [24] have studied students’ views on landscapes worth conserving and the landscapes that affect and support their well-being. The participants were Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish students from grades 3 to 6. The students drew the landscapes they wanted to conserve. The students from all three countries preferred water, forest, and yard landscapes. In the drawings of natural landscapes, the most recurring themes were sunrise and sunset, as well as forest, beach, and mountain landscapes. Physical well-being was manifested in the opportunity to jog and walk, and social well-being was reflected in the presence of friends, relatives, and animals.

In the last study [25] presented here, 9–14-year-old Gambian and Kenyan pupils were asked to draw a landscape they wanted to conserve. Over half of the pupils depicted the built environment, one-third the social environment, and only every tenth pupil the natural environment. The drawings showed that the pupils’ conceptions of landscapes were mostly related to their social environment. The lack of natural landscapes in the Gambian drawings was particularly interesting because it indicated that the pupils did not have much regard for natural landscapes and their intrinsic value. According to the researchers, the lack might indicate that the pupils had little experience with or exposure to visual representations of untouched nature, which could have allowed them to make a connection with the natural landscape.

This article contributes to knowledge regarding early childhood education student teachers’ mental images of the environment using drawing as a research method. Mirroring the results of the above-mentioned studies, one could expect the student teachers to depict the natural environment more often than the built environment. In addition, the premise is that people are not depicted frequently in the drawings. The aforementioned studies do not report if nature was somehow humanized in the pupils’ drawings, which, on the contrary, is one point of interest in this research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Drawings and Reflections

The dataset of this article consists of drawings (n = 106) made by Finnish early childhood education student teachers and their written reflections (n = 40). The student teachers took part in a course entitled ‘Environmental Education and Primary Science’ at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki. The student teachers were asked to draw the environment as it is typically presented for children, among others, in children’s literature. Each student was given one sheet of A4 paper for drawing. Early childhood education student teachers produced the drawings on Monday, 12; Tuesday, 13; and Wednesday, 14 March 2018. There were one hundred women and six men among the students. The mean age of the student teachers was 25 years, and the age range was 19–53 years. Any other type of background information was not collected.

The student teachers were introduced to the drawing task after the first lecture, which was mandatory for them. During the lecture, Palmer’s [14] tree model and the four approaches to the concept of the environment (Figure 2) were presented to the student teachers. Therefore, the student teachers were given an opportunity to reflect on how they understand the concept of the environment and how the first lecture of the ‘Environmental Education and Primary Science’ course affected their thinking by writing on the back side of their drawings. Because the reflection was not mandatory to write, altogether, 40 student teachers used this opportunity to write a short reflection. Thus, a few examples of the reflections are given in this article, but the main dataset is the environmental drawings. The excerpts of the reflections included here were translated from Finnish to English, and standard punctuation was added for readability [26].

3.2. Content Analysis

A qualitative content analysis was performed on the drawings, utilizing the concepts of geography introduced in Section 2. The content analysis began by naming the elements of the drawings according to how they embodied the built and the natural environments [27]. The so-called exhaustive coding categories were used to classify the elements of the natural environment and the built environment. In practice, one dominant element from both the natural environment and the built environment was named from each drawing [28,29]. The reason for this was the richness of the visual material, which made it impossible to calculate everything that the drawings presented [30]. For instance, if the drawing depicted mountains, the drawing was not included in the category of forests, even though there were often some trees in addition to mountains in the same drawing. In other words, the mountains were interpreted as the dominant element of the natural environment because they were usually drawn larger than the forests.

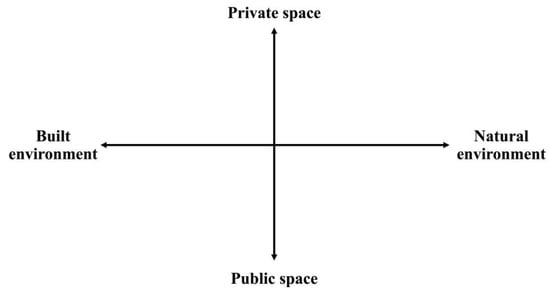

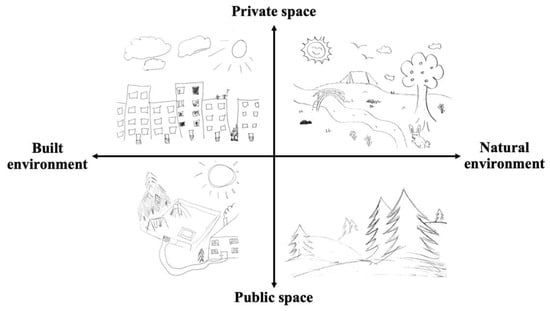

In addition to the degree of human activity in the environment (i.e., natural environment–built environment), the drawings were examined to see how they embodied private space and public space [27]. It was most meaningful to look at the boundary between public space and private space in the context of the built environment because, for instance, the forests can be thought of as representing public space. This is because of the so-called ‘everyone’s rights’ (before ‘everyman’s rights’) and the codes of conduct on private lands that enable hiking and camping in privately owned forests in Finland and other Nordic countries. In practice, this was executed by placing the results of the first round of the content analysis into four fields. The four fields are made of two axes: the horizontal axis between the built environment and the natural environment and the vertical axis between public space and private space (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The four fields used to organize the most common elements in the drawings, adapted and modified from [27] (p. 223).

In addition to the two rounds of qualitative content analysis described above, a special point of interest was to examine the presence of people and the humanization of nature in the drawings. In the drawings, inanimate nature was most often humanized by presenting the sun with a smiling face. Similarly, living nature was humanized by depicting animals and flowers with smiling faces.

3.3. Limitations

When it comes to visual methodology, there are some benefits and challenges, as there are with all the methods. Visual methods are especially fruitful in situations where the researcher is interested in the participants’ mental images, opinions, and emotions [31,32]. By drawing, it is possible to present phenomena that cannot be presented by writing or photography and vice versa [33,34]. A photograph tends to capture a moment frozen in time, whereas a drawing is an embodied physical act influenced by the participant’s emotions, perceptions, and experiences [35]. For instance, it would not have been possible to notice the student teachers’ tendency to humanize nature—such as depicting the sun with a smiling face—with photography. On the other hand, the boundary between public space and private space was difficult to determine in terms of the depicted forests and water elements in the drawings.

Because the materials produced by visual methods are ambiguous, it is worthy to supplement them with, for example, interviews or questionnaires [36]. In this research, the student teachers were given an opportunity to elaborate on their understanding of the concept of the environment on the back side of their drawing. However, these reflections do not comment on the drawings per se. It is also good to keep in mind that representations produced with visual methods are never objective or neutral, as they present the world through the choices and perspectives of the author [32,37].

Another limitation is the influence of dominant images in circulation in the media and popular culture [35,37]. For instance, in a study of young people’s representations of urban scape, it was found that the view of cities presented in news media affected the perceptions of the participants [38]. Therefore, it is rather challenging to elaborate on how much the drawings in this article depict the student teachers’ mental images of the environment and how much their mental images of the environmental illustrations are influenced by children’s literature.

4. Results

4.1. Drawings

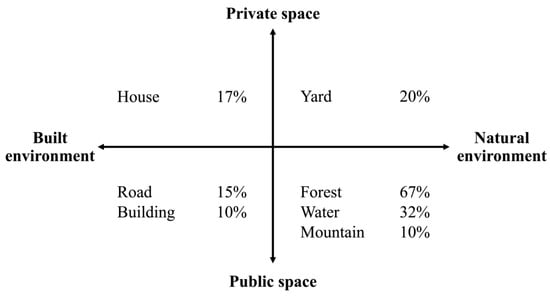

Figure 4 shows the most common elements of the early childhood education student teachers’ drawings (n = 106) and their relation to the built environment and the natural environment, as well as to private space and public space. The most common element of the natural environment was forests (67%). In addition, 32% of the drawings included an element of water, such as a lake, a river, or the sea. Ten percent of the drawings described mountains. In addition to mountains, forests were often present in these drawings, but due to exhaustive coding categories, forests were not taken into account in these cases [28,29]. When it comes to private space, the yard (20%) was the most common element in the context of the natural environment. Elements such as a tree—or two, at the most—grass, and flowers were used to illuminate the yards. The tree(s) in the yard was often recognizable as an apple tree (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The most common elements in the drawings.

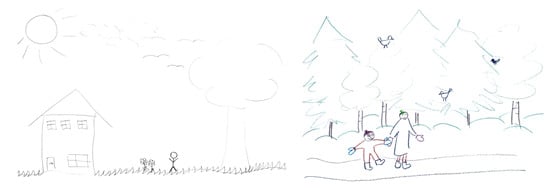

Figure 5.

A typical drawing of the environment (by a 20-year-old woman).

The built environment was represented by buildings in 27% of the drawings. Of these drawings, 17% had one building and 10% had more than one. Private space was mostly represented by buildings recognizable as single-family houses (17%). They typically had one door, a chimney, and a few windows (Figure 5). In addition to detached houses, cars (3%), tents (2%), and hammocks (2%) appeared in a few drawings. Roads and paths were the dominant elements of the built environment in 15% of the drawings. Sometimes, it was difficult to distinguish a road or a path from a river, but often, lines depicting waves were drawn to illuminate the river. In addition, public space in the built environment was represented by playgrounds (5%), bridges (2%), swings (2%), piers (2%), and parking lots (2%)—in addition to a “market” and a “supermax” named in individual drawings. Other individual elements of the built environment were, for instance, a fence, a pasture, a birdhouse, and a rowboat.

A total of 51% of the drawings did not present any elements of the built environment. In turn, people were missing in 83% of the drawings. In the drawings that did depict people, they were mostly represented as stick figures. It was difficult to reason the role people had or what they were doing in the environments depicted in these drawings. In Figure 6, two examples of drawings depicting people are given: a stick figure as well as an adult and a child with a smiling face. By contrast, 70% of the drawings presented other animals. Of these drawings, 25% depicted animals and flowers as smiling or sleeping, often with the letters “zzz”. The smiling sun was found in seven percent of the drawings, whereas the plain sun was depicted in 51% of the drawings. A smiling moon was found in two drawings.

Figure 6.

Examples of people in the drawings: a stick figure (by a 21-year-old woman) and an adult and a child with a smiling face (by a 34-year-old woman).

In Figure 7, there are four more examples of the early childhood education student teachers’ drawings categorized according to the dimensions of the built environment, the natural environment, private space, and public space. The drawing depicting the buildings was made by a 22-year-old man, the playground was drawn by a 22-year-old woman, the natural environment with the tent and the bridge was drawn by a 21-year-old woman, and the spruce forest was drawn by a 21-year-old woman. Even though the tent is human-made, it was one of the few elements that could be interpreted to represent private space in the context of the natural environment, alongside the yards and the hammocks.

Figure 7.

Exemplary environmental drawings.

Six of the drawings can be connected to the theme of the hydrological cycle, which is a traditional topic in environmental education [3]. Of these six cases, two drawings depicted clouds with clear droplets of water. The snowman was depicted in three drawings; in one of these drawings, it was also snowing. One of the drawings depicted lightning; thus, it is an interesting question to ponder whether it was possibly raining in the depicted landscape as well. In addition, six drawings depicted the nighttime with the moon and the stars.

In most of the drawings, the natural environment was presented as ideal; that is, they did not depict any environmental problems. In previous studies, even romantic features have been associated with the environment [2,39]. Only two exceptions were found: In one drawing by a 21-year-old woman, there was a sad-looking, melting snowman, which could be connected to the theme of either the arrival of spring or possibly climate change (Figure 8). Another drawing by a 23-year-old woman shows how the stages of meat processing are represented for children. In the drawing, the slaughterhouse is named a “happy place” (Figure 8). Otherwise, none of the drawings presented scary, dangerous, or controversial themes (cf.) [11].

Figure 8.

Two exemplary drawings depicting the environment as non-ideal: the sad-looking, melting snowman (by a 21-year-old woman) and the stages of meat processing (by a 23-year-old woman).

4.2. Reflections

Altogether, 40 students reflected on their understanding of the concept of the environment and how the first lecture of the ‘Environmental Education and Primary Science’ course possibly affected their thinking. It became evident that the student teachers thought that nature and the environment could be regarded as synonyms: “During the lecture, I realized that I often confuse the concepts of nature and the environment and use them as synonyms” (21-year-old woman). The natural environment was emphasized by some of the student teachers: “The word environment made me think of a forest” (21-year-old woman). On the other hand, the reflections showed incorrect preconceptions about whether the built environment belongs to the concept of the environment: “I thought that the environment meant mostly nature and not buildings” (20-year-old woman). One student teacher reflected on the role of humans as part of nature: “It occurred to me whether humans are part of nature” (42-year-old woman).

However, the first lecture of the ‘Environmental Education and Primary Science’ course expanded some of the student teachers’ understandings of the environment. For instance, a 22-year-old woman wrote the following in her reflection: “The first mental image that immediately came to my mind was nature, which I drew a picture of. The first lecture made me think the environment as a whole, including the built environment, such as the cities”. In addition, a 27-year-old woman stated the following: “When I talk about the environment, I often mean nature, such as trees and forests. The lecture made me think that the environment is much more than the forests, including the built milieu, parks, and so on”.

For some of the student teachers, the inclusion of the built environment in the concept of the environment was known from the very beginning: “I consider the environment to mean both the natural and the built environments” (21-year-old woman) and “The first thing that came to my mind was nature, recycling, and the urban landscape” (21-year-old woman). According to a 39-year-old man, the built environment is emphasized too much in children’s literature: “In children’s books, the environment is often about the built environment, that is, the city. Nature is underrepresented. Everyone is still happy. Values that destroy nature are reproduced”. In the opinion of a 20-year-old woman, environmental problems are not presented to children: “Everything is fine, life is smiling, and the animals are happy”.

5. Discussion

In this article, Finnish early childhood education student teachers’ mental images of the environment have been examined with the help of environmental drawings. The main result is that student teachers do not associate the built environment or people with the concept of the environment. That is, half of the drawings did not depict any elements of the built environment, and more than 80% of the drawings lacked people. The absence of people in environmental drawings aligns with findings from previous studies [22]. People have been absent even in drawings depicting urban environments [38]. When it comes to the number of people in environmental drawings, it seems that it does not matter whether the word ‘environment’ or the word ‘landscape’ is used in the instruction.

As it turned out, studying student teachers’ mental images of the environment is challenging. This is because the instruction for the student teachers was to draw the environment as it is typically presented for children, among others, in children’s literature. As stated in Section 3, it is, therefore, rather difficult to elaborate to what extent the drawings represent the student teachers’ mental images of the environment and to what extent their mental images of the environmental illustrations in children’s literature. The instruction may have mainly shaped the student teachers’ tendency to humanize living nature, as 25% of all the animals and flowers were depicted with smiling faces.

All in all, the concept of the environment is ambiguous and, therefore, difficult to define [2,3]. One of the challenges is that, in everyday language, the environment often means the same as nature, or alternatively, the environment is thought to refer only to the natural environment [4]. Indeed, previous studies show that early childhood educators, too, consider the concepts of nature and the environment synonyms. Still, some of the early childhood education student teachers wrote in their reflections that the first lecture of the ‘Environmental Education and Primary Science’ course had little effect on their ways of understanding the concept of the environment. Bela Yavetz, Daphne Goldman, and Sara Pe’er [39] (p. 367) have noticed the same in their research, as they report that student teachers’ understanding of the environment was essentially basic, and their professional preparation did not lead to substantial development in this.

For the aforementioned reasons, the student teachers’ mental images and understandings of both the concept of nature and the concept of the environment need reflection [10]. First, if future early childhood educators do not see conceptual differences between nature and the environment, how can it be guaranteed that children will become sufficiently familiar with the built environment, as well? This is an important question because, according to the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care [6], children should have opportunities to explore both the natural environment and the built environment.

Second, if people are not seen as part of the environment, what does the role of humans as the cause and moderator of environmental problems look like? To deal with human-caused environmental problems, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, an understanding of the interaction between humans and the environment is needed. However, it is good to keep in mind that children are not to be burdened with environmental problems in early childhood education. Instead, the focus should be on practicing the skills in order to act for the good of the environment [3,14,40].

Third, in order for a person to develop relationships with nature and the environment, a conceptual understanding of nature and the environment is needed. Children’s perceptions of what is meant by the concepts of nature and the environment are influenced by the meanings produced by the social environment, that is, early childhood educators around them. One of the challenges is that a binary opposition between the environment and society can be found in teachers’ thinking [41]. Because of this, the social and cultural dimensions of the environment are not fully recognized [42]. Here, educators can benefit from incorporating geographical concepts, such as landscape, meaningful places, and architectural styles in different decades, in their pedagogical activities, even if they do not have a strong background in geography or environmental studies [43]. In addition, observing the characters of the built environment and seasonal changes that take place in the urban environment will develop children’s and young people’s environmental sensitivity as well [44].

When it comes to the style of pedagogy that is most appropriate for environmental education, Finnish teachers rarely use engaging, experiential, hands-on, real-world approaches in their teaching [45,46]. Even during their free time, the mobility of children and young people is more limited and scheduled nowadays. The concept of ‘bubble-wrap generation’ has been used to describe children whose parents figuratively wrap their children in bubble-wrap to protect them from the dangers of the surrounding environment [47]. The ‘backseat generation’, on the other hand, has been used to describe children whose relationship with the environment is structured according to what they see from the car window when their parents drive them from one place to another [48].

In light of the concepts of the bubble-wrap generation and the backseat generation, the extensive number of forests in the student teachers’ environmental drawings in this study is a positive finding—especially if it will be concretized in early childhood education as weekly field trips to nearby forests with the children. Environmental education carried out in forests develops children both physically, emotionally, and cognitively [3,49]. At the same time, children’s relationships with nature and the environment develop and deepen as meaningful places are created outside their homes and kindergartens [40]. The immediate surroundings should be a safe place for children, which at the same time offers experiences of joy and a sense of survival [50]. Because of this, it is understandable that the student teachers depicted the environment as safe and ideal in their drawings.

6. Conclusions

To conclude, it is of great importance that student teachers have diverse perceptions of the environment. In this research, it is suggested that student teachers who have a better conceptual understanding of the environment are more likely to provide children with opportunities for investigating both the natural environment and the built environment. Therefore, teacher training should include a more nuanced understanding of environment–human relations and give student teachers a more extensive toolkit for actively exploring the environment with children. At the moment, people are the biggest force that changes the environment. If environmental problems, or wicked problems, are to be solved, people must take an active approach to environmental issues [40]. In order for future teachers to act as role models for the children and to discuss environmental issues with them, student teachers must understand the role and responsibility humans have in shaping the environment [51]. Therefore, it is essential that student teachers reach an understanding that both humans and the built environment are included in the concept of the environment [39].

In future research, the work could be extended to children’s literature. For instance, it would be interesting to compare the results of this study, that is, the elements of environmental drawings made by early childhood education student teachers, with the elements of environmental illustrations in children’s books. In addition, the ways in which old and current children’s books visualize the environment and humans could be worth studying: How has the ratio between forests and the built environment changed over the decades in the illustrations? What sorts of roles do adults and children have in the illustrations? It would also be interesting to deepen the research on student teachers’ perceptions of the cultural conventions and pedagogical ways of presenting the environment visually in materials aimed at children.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In Finland, research with human participants must comply with the guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK (https://tenk.fi/en/advice-and-materials/guidelines-ethical-review-human-sciences, accessed on 19 October 2023). The University of Helsinki has undertaken to comply with TENK’s guidelines. The guidelines do not cover medical research as defined by law (Medical Research Act 488/1999) or other research designs where ethical review is a separate obligation laid down by law. Ethical review is to be carried out prior to gathering data if the research contains one or more of the following factors: 1. Participation in the research deviates from the principle of informed consent. Participation is not, for example, voluntary, or the subject is not given sufficient or correct information about the research. 2. The research involves intervening in the physical integrity of research participants. 3. The focus of the research is on minors under the age of fifteen without separate consent from a parent or carer or without informing a parent or carer in a way that would enable them to prevent the child’s participation in the research. 4. Research that exposes participants to exceptionally strong stimuli. 5. Research that involves a risk of causing mental harm that exceeds the limits of normal daily life to the research participants, their family members, or others closest to them. 6. Conducting the research could involve a threat to the safety of participants or researchers, their family members, or others closest to them. If none of the above factors is met, an ethical review is not required.

Informed Consent Statement

The student teachers were informed that if they willingly give their drawings to the author, (a) the drawings will be treated as a scientific dataset, and (b) the drawings can anonymously be published in an academic paper. Participation was voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

Access to the student teachers’ environmental drawings and reflections can be inquired into from the author with the permission of the student teachers.

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful to the student teachers who participated in the study. I also thank the reviewers and the guest editor of the special issue for their constructive feedback which enabled me to refine the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Tani, S. The environments of learning environments: What could/should geography education do with these concepts. J. Res. Didact. Geogr. (J-READING) 2013, 2, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Flogaitis, E.; Agelidou, E. Kindergarten teachers’ conceptions about nature and the environment. Environ. Educ. Res. 2003, 9, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikka-Nihti, M.; Suomela, L. Iloa ja Ihmettelyä: Ympäristökasvatus Varhaislapsuudessa; PS-kustannus: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cantell, H.; Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E.; Tani, S. Ympäristökasvatus: Kestävän Tulevaisuuden Käsikirja; PS-kustannus: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cantell, H.; Rikkinen, H.; Tani, S. Maantieteen ainedidaktiikka tutkimuksen kohteena. In Ainedidaktiikka Tutkimuskohteena ja Tiedonalana; Kallioniemi, A., Virta, A., Eds.; Suomen Kasvatustieteellinen Seura: Turku, Suomi, 2012; pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Agency for Education. National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care 2022; National Board of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Russ, A.; Krasny, M.E. (Eds.) Urban Environmental Education Review; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, S. Children in the natural world. In Young Children and the Environment; Davis, J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 44–73. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, F.; Castéra, J.; Clément, P. Teachers’ conceptions of the environment: Anthropocentrism, non-anthropocentrism, anthropomorphism and the place of nature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willamo, R. Kokonaisvaltainen Lähestymistapa Ympäristönsuojelutieteessä: Sisällön Moniulotteisuus Ympäristönsuojelijan Haasteena. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 12 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Duhn, I.; Malone, K.; Tesar, M. Troubling the intersections of urban/nature/childhood in environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Benzon, N. Discussing nature, ‘doing’ nature: For an emancipatory approach to conceptualizing young people’s access to outdoor green space. Geoforum 2018, 93, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhunkorva, R.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Paaskoski, L. Metsäsuhteiden Kenttä; Lusto: Punkaharju, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, J. Environmental Education in the 21st Century: Theory, Practice, Progress and Promise; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E. Ympäristöaiheet humanistis-yhteiskunnallisten aineiden opetuksessa. In Näin Rakennat Monialaisia Oppimiskokonaisuuksia; Cantell, H., Ed.; PS-kustannus: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015; pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rautio, P.; Hohti, R.; Leinonen, R.-M.; Tammi, T. Reconfiguring urban environmental education with ‘shitgull’ and a ‘shop’. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D. Geography and Vision, 2nd ed.; I. B. Tauris: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, J.; Kraftl, H. Cultural Geographies: An Introduction; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Linkola, H. “Niin Todenmukainen Kuin Mahdollista”: Maisemavalokuva Suomalaisessa Maantieteessä 1920-luvulta 1960-luvulle. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 14 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tani, S. Oikeus oleskella? Hengailua kauppakeskuksen näkyvillä ja näkymättömillä rajoilla. Alue Ympäristö 2011, 40, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Välimaa, I. Mielipaikoista luokkahuoneeseen: Nuorten elämismaailman yhdistäminen maantieteen opetukseen. Terra 2012, 124, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Panula, E.; Eloranta, V. The landscapes that Finnish children and adolescents want to conserve: A study of pupils’ drawings in Basic Education. Nordidactica 2011, 1, 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yli-Panula, E.; Persson, C.; Jeronen, E.; Eloranta, V.; Pakula, H.-M. Landscape as experienced place and worth conserving in the drawings of Finnish and Swedish students. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Panula, E.; Jeronen, E.; Matikainen, E.; Persson, C. Conserve my village: Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish students’ valued landscapes and well-being. Sustainability 2022, 14, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Panula, E.; Jeronen, E.; Eilola, S.; Pakula, H.-M. The Gambian and Kenyan pupils’ conceptions of their valued landscapes and animals. In Arvot ja Arviointi: Ainedidaktisia Tutkimuksia; Kallio, M., Krzywacki, H., Poulter, S., Eds.; Suomen Ainedidaktinen Tutkimusseura: Helsinki, Finland, 2019; pp. 225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rajala, A.; Akkerman, S.F. Researching reinterpretations of educational activity in dialogic interactions during a fieldtrip. Learn. Cult. Soc. Inter. 2019, 20, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, R. Tutkija visuaalisen aineiston tulkitsijana. Terra 2012, 124, 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jokela, S.; Raento, P. Collecting visual materials from secondary sources. In An Introduction to Visual Research Methods in Tourism; Rakić, T., Chambers, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Seppä, A. Kuvien Tulkinta; Gaudeamus: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jokela, S. Tourism, Geography and Nation-Building: The Identity-Political Role of Finnish Tourism Images. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 22 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tani, S. Eletty ja kuvattu kaupunki: Nuorten kaupunkipiirrokset tulkinnan kohteina. In Lapsuuden Muuttuvat Tilat; Strandell, H., Haikkola, L., Kullman, K., Eds.; Vastapaino: Tampere, Finland, 2012; pp. 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 5th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Sociolinguistics and social semiotics. In The Routledge Companion to Semiotics and Linguistics; Cobley, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Briell, J.; Elen, J.; Depaepe, F.; Clarebout, G. The exploration of drawings as a tool to gain entry to students’ epistemological beliefs. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 8, 655–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kearns, R.; Eggleton, K.; van der Plas, A.; Coleman, T. Drawing and graffiti-based approaches. In Creative Methods for Human Geographers; von Benzon, N., Holton, M., Wilkinson, C., Wilkinson, S., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2021; pp. 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.; Elen, J. ‘Picturing’ instruction: An exploration of higher education students’ knowledge of instruction. Stud. High. Educ. 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, S. Building a facade for Finland: Helsinki in tourism imagery. Geogr. Rev. 2011, 101, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béneker, T.; Sanders, R.; Tani, S.; Taylor, L. Picturing the city: Young people’s representations of urban environments. Child. Geogr. 2010, 8, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavetz, B.; Goldman, D.; Pe’er, S. How do preservice teachers perceive ‘environment’ and its relevance to their area of teaching? Environ. Educ. Res. 2014, 20, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People Nat. 2020, 2, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C. The environment/society disconnect: An overview of a concept tetrad of environment. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 41, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E. Ympäristö Ylittää Oppiainerajat: Arvolatautuneisuus ja Monialaisuus Koulun Ympäristöopetuksen Haasteina. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 12 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, D.; Hagelman, R. Geographic and environmental themes in children’s literature. J. Geog. 2021, 120, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, S. Reflected places of childhood: Applying the ideas of humanistic and cultural geographies to environmental education research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloranta, S. Koulun Toimintakulttuurin Merkitys Kestävän Kehityksen Kasvatuksen Toteuttamisessa Perusopetuksen Vuosiluokkien 1–6 Kouluissa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 22 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, L.-A.; Sjöblom, P.; Hofman-Bergholm, M.; Palmberg, I. High performance education fails in sustainability? A reflection on Finnish primary teacher education. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, K. The bubble-wrap generation: Children growing up in walled gardens. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, L. It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban children’s daily use of space. Child. Geogr. 2005, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.; Barnes, M.; Jordan, C. Do experiences with nature promote learning? Converging evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linzmayer, C.D.; Halpenny, E.A. ‘I might know when I’m an adult’: Making sense of children’s relationships with nature. Child. Geogr. 2014, 12, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.O.; Hakari, S. Early childhood educators and sustainability: Sustainable living and its materialising in everyday life. Utbild. Demokr. 2018, 27, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).