Teaching English as a Second Language in the Early Years: Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices in Finland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What characterises teachers’ pedagogical planning, teaching practices, and assessment of language learning in early L2 classrooms in Finland?

- (2)

- How do teachers perceive opportunities and challenges in early L2 classrooms in Finland?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Second Language Teaching Theories in the Early Years

2.2. Second Language (English) Teaching in Finnish Context

3. Research Design

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

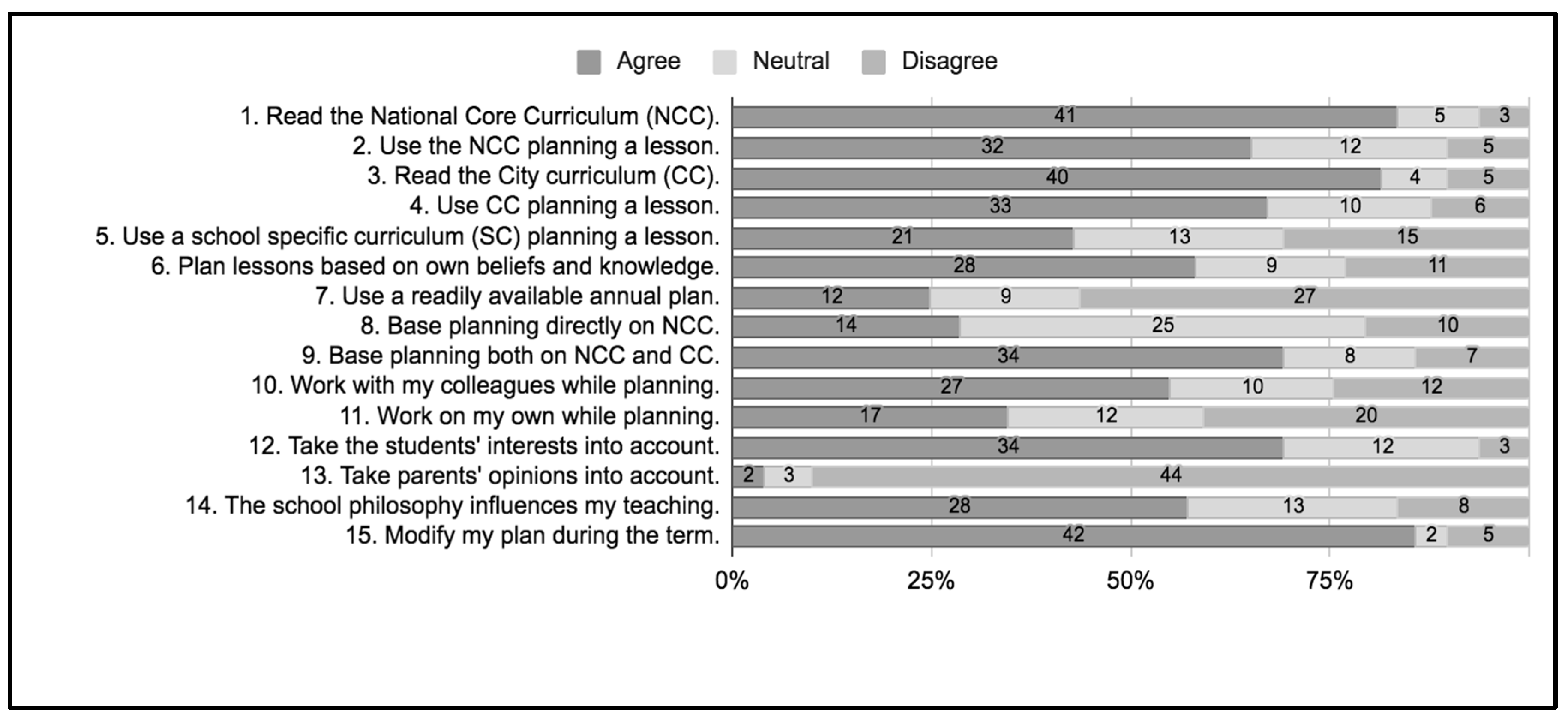

4.1. Planning in Early L2 Classrooms

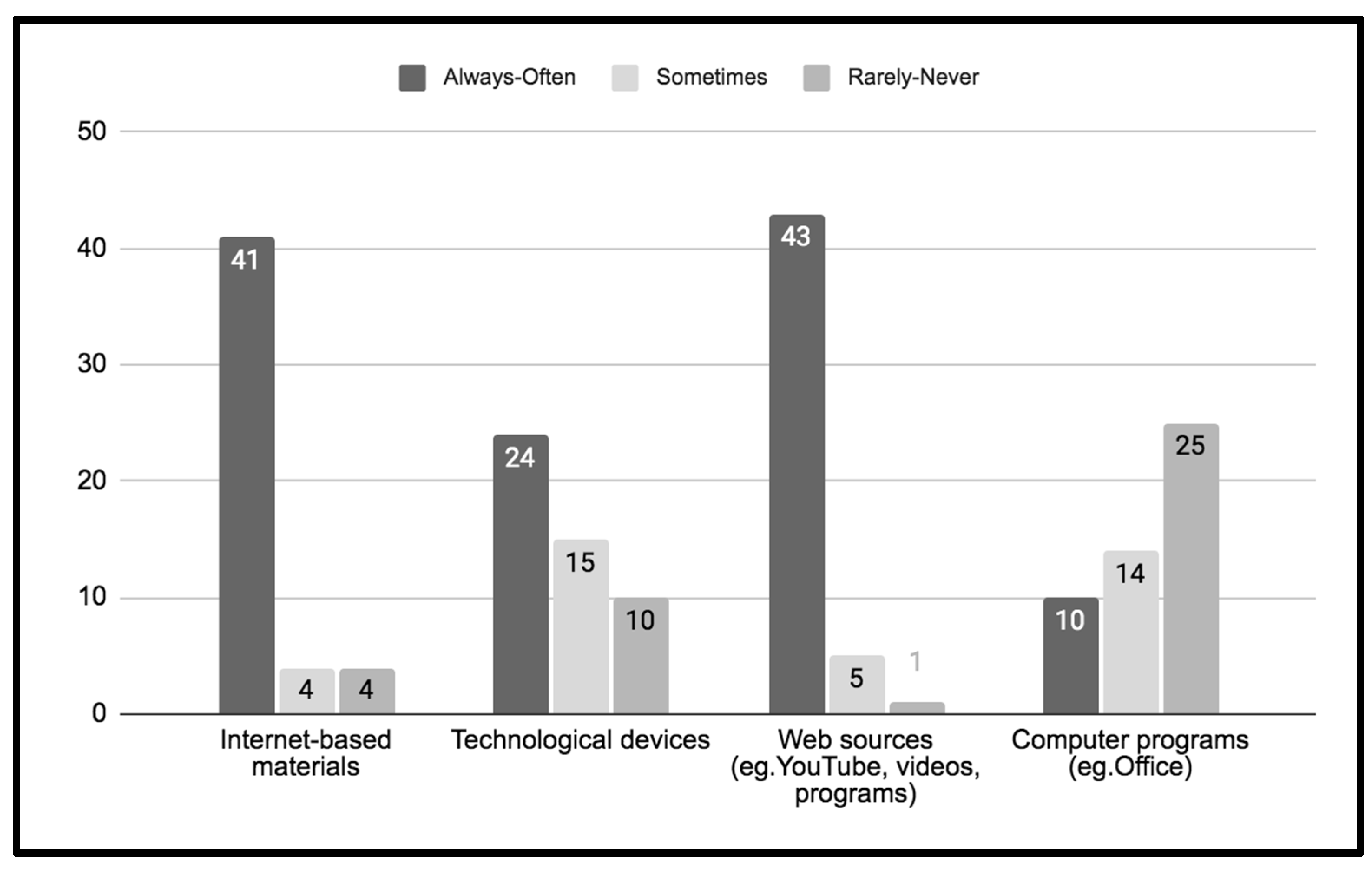

4.2. Teaching Practices in Early L2 Classrooms

“What I use depends on what we’re practising each time. For 1–2 graders I try to include some new content every time, but not too much. We have shared activities, pairwork and individual exercises.

Speaking and listening at first, then recognising words and then learning to write.

Mainly pictures, songs with choreography, small dialogues. Lots of listening, repeating and using the language orally. Also, games and exercises.”

4.3. Assessment Methods in Early L2 Classrooms

“I don’t think strong assessment is necessary with 1–2 graders. More important is to get to know the language and enjoy it.

I would like to collaborate more with other teachers in planning and assessment methods but usually they don’t have the time.

Two hours per week is pretty decent as long as it’s not in a 90 or two 45-min blocks. At least the other 45 min needs to be spread out along the entire week in 5–10-min blocks.”

4.4. Teacher Perspectives on Early L2 Education: Opportunities and Challenges

“There are fewer negative attitudes towards language learning.Learning pronunciation and vocabulary items easily.Children are enthusiastic. They are very motivated to learn a new language.Teaching English to younger children is very rewarding, because they’re keen learners.”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnstone, R. Introduction. In Learning through English: Policies, Challenges and Prospects; Johnstone, R., Ed.; British Council: London, UK, 2010; pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Key Data on Teaching Languages at School in Europe—2017 Edition; Eurydice Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017.

- Huhta, A.; Leontjev, D. Kielenopetuksen Varhentamisen Kärkihankkeen Seurantapilotti, Final Report; University of Jyvaskyla, Centre for Applied Language Studies: Jyvaskyla, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Inha, K. Vuosi Kärkihankentta Takana, Kieliverkoston Verkkolehden Teemanumero, [Online]. 2018. Available online: https://www.kieliverkosto.fi/fi/journals/kieli-koulutus-ja-yhteiskunta-kesakuu-2018/vuosi-karkihanketta-takana (accessed on 13 June 2019).

- Moyer, A. Age, Accent and Experience in Second Language Acquisition: An Integrated Approach to Critical Period Inquiry; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, L. Challenging Common Myths about Young English Language Learners; Foundation for Child Development Policy Brief, Advancing PK-3: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alstad, G.T.; Sopanen, P. Language orientations in early childhood education policy in Finland and Norway. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 7, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, S.; Lourenço, M. (Eds.) Early Years Second Language Education: International Perspectives on Theory and Practice; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, M.; Timple-Laughlin, V. Assessing young learners’ foreign language abilities. Lang. Teach. 2020, 54, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, P.; Johnstone, R.; Kubanek, A. The Main Pedagogical Principles Underlying the Teaching of Languages to Very Young Learners. Languages for the Children of Europe: Published Research, Good Practice and Main Principles. European Commission Report. 2006. Available online: http://ec.europa.e/ducatio/olicie/an/o/oungsum_en.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Rasinen, T. Näkökulmia Vieraskieliseen Perusopetukseen: Koulun Kehittämishankkeesta Koulun Toimintakulttuuriksi; Jyväskylän yliopisto: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wewer, T. Assessment of Young Learners’ English Proficiency in Bilingual Content Instruction (CLIL) in Finland: Practices, Challenges, and Points for Development. In Assessment and Learning in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Classrooms; de Boer, M., Leontjev, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remillard, J.T.; Van Steenbrugge, H.; Machalow, R.; Koljonen, T.; Krzywacki, H.; Condon, L.; Hemmi, K. Elementary teachers’ reflections on their use of digital instructional resources in four educational contexts: Belgium, Finland, Sweden, and US. ZDM—Math. Educ. 2021, 53, 1331–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.; Priestley, M.; Robinson, S. The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, M.; Mihaljević Djigunović, J. All shades of every colour: An overview of early teaching and learning of foreign languages. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 31, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiek, J.; Clandinin, D.J. Curriculum and teacher development. In Journeys in Narrative Inquiry; Clandinin, D.J., Ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siuty, M.B.; Leko, M.M.; Knackstedt, K.M. Unraveling the Role of Curriculum in Teacher Decision Making. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2016, 41, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNBE. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014; Publications 2016:5; Finnish National Board of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Purola, K.; Kuusisto, A. Parental participation and connectedness through family social capital theory in the early childhood education community. Cogent Educ. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enever, J. ELLiE: Early Language Learning in Europe; The British Council: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Enever, J. The Advantages and Disadvantages of English as a Foreign Language with Young Learners. In Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3–12 Year Olds; Bland, J., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2015; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rixon, S. Primary English and Critical Issues: A Worldwide Perspective. In Teaching English to Young Learners: Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3–12 Year Olds; Bland, J., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2015; pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen, K. A principled, personalised, trusting and child-centric ECEC system in Finland. In The Early Advantage 1: Early Childhood Systems that Lead by Example—A Comparative Focus on International Early Childhood Education; Kagan, S., Ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 72–98. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Early Childhood Development Overview. 2022. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/early-childhood-development/overview/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Lenneberg, E.H. Biological Foundations of Language; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Penfield, W.; Roberts, L. Speech and Brain Mechanisms, 3rd ed.; Atheneum: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, M. The age factor in context. In The Age Factor and Early Language Learning; Nikolov, M., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, A. Teaching Young Learners; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hiver, P.; Al-Hoorie, A.H.; Vitta, J.P.; Wu, J. Engagement in language learning: A systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021, 13621688211001289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.D. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: White Plains, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.; Rodgers, T. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. Task-Based Language Learning and Teaching; Oxford Applied Linguistics: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, J.J. The total physical response approach to second language learning. Mod. Lang. J. 1969, 53, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashen, S.D.; Terrell, T.D. The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R. Language Teaching Research and Pedagogy; Wiley-Balckwell: West Sussex, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, D.H. On Communicative Competence. In The Communicative Approach to Language Teaching; Brumfit, C.J., Johnson, K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Broström, S. A dynamic learning concept in early years’ education: A possible way to prevent schoolification. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2017, 25, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantolf, J.P. Sociocultural theory and second language development: State-of-the-art. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 2006, 28, 67–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society, the Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cekaite, A.; Aronsson, K. Language Play, a Collaborative Resource in Children’s L2 learning. Appl. Linguist. 2005, 26, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (2019). PISA 2018 Results, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/pisa-2018-results-volume-i-5f07c754-en.htm (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Steiner-Khamsi, G.; Waldow, F. (Eds.) Understanding PISA’s Attractiveness: Critical Analyses in Comparative Policy Studies; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- VOPS. Perusopetuksen Opetussuunnitelman Perusteiden 2014 Muutokset Ja Täydennykset Koskien A1-Kielen Opetusta Vuosiluokilla 1–2; Opetushallitus: Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Education Statistics Finland. Perusopetuksen 1–6 Luokkien A-Kielivalinnat; [Selection of A-languages in grades 1-6 in basic education.] Vipunen; Statistics Finland, the Ministry of Culture and Education and the Finnish National Agency for Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Inha, K.; Huhta, A. Kieltenopetus vuosiluokilla 1–3: Miten oppilaat siihen suhtautuvat ja mitä tuloksia sillä saavutetaan puolen vuoden opiskelun aikana? In Pidetään Kielet Elävinä—Keeping Languages Alive—Piemmö Kielet Elävinny; Kok, M., Massinen, H., Moshnikov, I., Penttilä, E., Tavi, S., Tuomainen, L., Eds.; Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistys ry. AFinLA:n vuosikirja: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2019; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D. English Language Teaching and Systematic Change 23 at the Primary Level: Issues in Innovation, Primary Innovations: Regional Seminar, A Collection of Papers; British Council: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2007; pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, M.; Djigunović, J. Recent research on age, second language acquisition and early foreign language learning. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2006, 26, 234–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, M.; Piispanen, M. The Early Bird Gets the Word. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2019, 12, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovellan, E. Teachers’ beliefs about learning and language as reflected in their views of teaching materials for Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). In Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Inha, K.; Kähärä, T. Introducing an Earlier Start in Language Teaching: Language Learning to Start as Early as in Kindergarten. 2018. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/introducing_an_earlier_start_in_language_teaching.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Hahl, K.; Pietarila, M. Class teachers, subject teachers and double qualified:conceptions of teachers’ skills in early foreign language learning in Finland. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2021, 13, 712–725. [Google Scholar]

- Data Protection Act. Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council (2016/679). 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679 (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity. (TENK, 2019). Ministry of Education and Culture. Available online: http://www.tenk.fi/en (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 11th ed.; Wadswoth: Belmont, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, J.; Czaja, R.; Blair, E. Designing Surveys; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 1-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- OPH. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/en/education-and-qualifications/national-core-curriculum-basic-education (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- OPH. Education in Finland. Finnish National Agency for Education. 2020. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/education-in-finland-2020_1.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Đurišić, M.; Bunijevac, M. Parental involvement as an important factor for successful education. Res. Insights Chall. Facil. Crit. Think. 2017, 7, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Vandenbroeck, M. (De)constructing parental involvement in early childhood curricular frameworks. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 26, 813–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helman, L.A.; Burns, M.K. What does oral language have to do with it? Helping young English-language learners acquire a sight word vocabulary. Read. Teach. 2008, 62, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, M.J. Assessing Children’s Learning; David Fulton: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Lankinen, T. Striving for Educational Equity and Excellence: Evaluation and Assessment in Finnish Basic Education. In Miracle of Education: The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools; Niemi, H., Toom, A., Kallioniemi, A., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wortham, S.C.; Hardin, B.J. Assessment in Early Childhood Education; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu, S.; Kumpulainen, K.; Kuusisto, A. Scaffolding Children’s Participation During Teacher-Child Interaction in Second Language Classroom. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Numbers of Teachers | Age | Experience in Teaching | Qualifications | Highest Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 female 1 male | 20–29 years: 10 30–39 years: 11 40–49 years: 18 50–59 years: 9 60 and over: 1 | Less than one year: 2 1–5 years: 13 5–10 years: 7 10–15 years: 14 15 years over: 13 | Class teacher: 29 English teacher: 17 Pre-school teacher: 1 Others: 2 (the qualification was not specified by the participants) | Master: 48 Bachelor: 1 |

| Always/Often | Sometimes | Rarely/Never | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual tasks | f | 27 | 13 | 9 |

| % | 55 | 27 | 18 | |

| Pair work | f | 39 | 9 | 1 |

| % | 80 | 18 | 2 | |

| Group work | f | 28 | 18 | 3 |

| % | 57 | 37 | 6 | |

| Role plays | f | 21 | 13 | 15 |

| % | 43 | 27 | 30 | |

| Competitions | f | 14 | 15 | 20 |

| % | 29 | 30 | 41 | |

| Music | f | 48 | 1 | 0 |

| % | 98 | 2 | 0 | |

| Hands-on tasks | f | 44 | 4 | 1 |

| % | 90 | 8 | 2 | |

| Handouts | f | 22 | 18 | 9 |

| % | 45 | 37 | 18 | |

| Move around class | f | 40 | 9 | 0 |

| % | 82 | 18 | 0 | |

| Outdoor activities | f | 6 | 14 | 29 |

| % | 12 | 29 | 59 | |

| Board games | f | 21 | 20 | 8 |

| % | 43 | 41 | 16 | |

| Draw, colour, label | f | 40 | 6 | 3 |

| % | 82 | 12 | 6 | |

| Pronunciation | f | 39 | 7 | 3 |

| % | 80 | 14 | 6 |

| Language | Always/Often | Sometimes | Rarely/Never | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | f | 12 | 9 | 28 |

| % | 25 | 18 | 57 | |

| Finnish | f | 25 | 16 | 6 |

| % | 51 | 33 | 12 |

| Always/Often | Sometimes | Rarely/Never | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using one specific textbook | f | 13 | 14 | 22 |

| % | 27 | 28 | 4 | |

| Using several textbooks | f | 22 | 12 | 15 |

| % | 45 | 24 | 31 | |

| Using own materials | f | 35 | 11 | 3 |

| % | 72 | 22 | 6 | |

| Using a ready material pack (including a textbook, workbook, flashcards, etc.) | f | 16 | 10 | 23 |

| % | 33 | 20 | 47 | |

| Need more materials at school | f | 32 | 9 | 8 |

| % | 65 | 18 | ||

| A classroom/language lab need | f | 14 | 19 | 15 |

| % | 29 | 40 | 31 | |

| Avoid using digital materials | f | 2 | 3 | 44 |

| % | 4 | 6 | 90 |

| Assessment of Teaching | SA/Agr | Neutral | Dis/SD | Median | Mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I assess the students’ performance regularly and keep track of the results. | f | 20 | 15 | 14 | 3 | 3 |

| % | 40.8 | 30.6 | 28.5 | |||

| 2. I monitor the students’ performance during the lesson and help them when they need it. | f | 46 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| % | 93.8 | 6.1 | 0.0 | |||

| 3. It is difficult for me to remember each student’s improvement in the lesson without a written assessment. | f | 13 | 11 | 24 | 3 | 2 |

| % | 26.5 | 22.9 | 48.9 | |||

| 4. I report the students’ assessment to the parents between the scheduled assessment talks. | f | 11 | 10 | 27 | 2 | 2 |

| % | 22.4 | 20.8 | 55.1 | |||

| 5. I discuss the students’ learning with the other staff and collaborate with them. | f | 29 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| % | 59.1 | 22.4 | 18.3 | |||

| 6. I collaborate with other language teachers at the school regarding teaching content, teaching activities, or assessment. | f | 34 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 4 |

| % | 69.3 | 12.2 | 18.3 | |||

| 7. Two hours a week for English language lessons is enough at early ages. | f | 45 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| % | 91.8 | 6.1 | 2.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koyuncu, S.; Kumpulainen, K.; Kuusisto, A. Teaching English as a Second Language in the Early Years: Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices in Finland. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121177

Koyuncu S, Kumpulainen K, Kuusisto A. Teaching English as a Second Language in the Early Years: Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices in Finland. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(12):1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121177

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoyuncu, Selma, Kristiina Kumpulainen, and Arniika Kuusisto. 2023. "Teaching English as a Second Language in the Early Years: Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices in Finland" Education Sciences 13, no. 12: 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121177

APA StyleKoyuncu, S., Kumpulainen, K., & Kuusisto, A. (2023). Teaching English as a Second Language in the Early Years: Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices in Finland. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121177