Abstract

The use of social–emotional learning (SEL) practices in online literature teaching has not yet been sufficiently researched. This study addresses this lacuna by identifying SEL practices mentioned by lecturers and preservice teachers (PSTs) as they reported on their respective experiences of teaching and learning in online literature lessons. Data were collected using three research tools: questionnaires were completed by 28 lecturers from four different teacher education colleges and 90 PSTS; semi-structured interviews were held with 12 of the literature PSTs; and a focus group was held with six lecturers. A data analysis revealed six major SEL-related themes mentioned by lecturers and PSTs as essential practices of online learning and teaching: building relationships, working collaboratively, emotional involvement, effective communication, dealing with conflicting feelings, and techno-pedagogic skills. These findings contribute to our understanding of online learning and teaching versatility and complexity. Considering these findings in light of existing theoretical models demonstrates that while five themes coincide with the skills included in the CASEL model, the sixth theme regarding techno-pedagogical skills is not part of the original model. These findings expand the applicability of the CASEL model from its original face-to-face learning context to the interaction between learners and lecturers in an online platform.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in the interest in social–emotional learning (SEL), manifested in both the scientific literature and in shifts occurring in education systems throughout the world [1]. Underlying this tendency is a consensus on the need to expand the goals of education, while addressing several varied components, among them, the need to develop 21st century skills [2]. The heightened interest in SEL can be understood in the context of the many changes affecting the realm of education, particularly the shift to online teaching and learning [3]. Hence, numerous organisations, international institutions, and education systems worldwide are addressing the topic and identifying it as a key element for coping effectively with the changing reality [4]. DePaoli et al. [5] noted the paucity of proper training for educational teams and the insufficient number of scientific findings demonstrating the successful use of SEL in schools, all of which weaken the likelihood of its optimal implementation.

Efforts are being made to take steps to examine and advance the implementation of SEL into education systems. Such efforts include formulating the image and characteristics of 21st century high school graduates and the type of SEL and skills they will have to demonstrate [6]. An examination of the sudden transition to distance learning during COVID-19 also indicates that SEL plays an important role in human development, particularly during times of crisis [7]. In this context and from a discipline perspective, no in-depth research has been completed on the application of SEL in literature teaching [8]. The current study’s goal was to bridge this gap by identifying the SEL practices that preservice teachers (PSTs) and lecturers addressed when they discussed their individual experiences of teaching and learning in online literature classes.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Approach to SEL in the Teacher Education Arena

Although there is no single and widely accepted definition for the concept of SEL, it can be generally described as related to a process in which students learn and apply a range of social, emotional, and behavioural skills and characteristics that are required for succeeding in school, in the workplace, in relationships, and in civic life [9]. SEL abilities include skills, knowledge, attitudes, and social–emotional tendencies that are required to formulate goals, regulate behaviours, construct relationships, and analyse and remember information, within contexts that aim to nurture these abilities [10]. SEL abilities also include emotional processes such as regulating emotions and demonstrating empathy, as well as interpersonal skills, such as understanding others’ perspectives and demonstrating social responsibility [11,12]. SEL-related processes should not be considered an independent content unit but rather an integral part of all educational and systemwide relationships. Hence, it is necessary to create the conditions and environment that promote and nurture such skills, characteristics, and tendencies, which, in turn, serve to promote optimal and productive functioning [13].

2.2. Preparing Educators to Integrate SEL into Their Respective Curricula

The SEL approach has affected the work of in-service and preservice teachers. Schonert-Reichl et al. [14] recommended that teacher education programmes address up-to-date SEL knowledge and consider PSTs’ ability to apply this knowledge not only in the contents of their lessons, but also in their behaviour in general. Other researchers have recommended including SEL content in all processes related to teacher education rather than assigning this topic unique courses. They claim that integrating SEL content into teacher education programmes has led to positive shifts in the perceptions and attitudes of PSTs [15]. However, SEL implementation is a complicated mission because developing students’ SEL requires teachers to develop their SEL abilities as well, and SEL teacher preparation is still deficient [5,16].

A theoretical model that considers the link between the social–emotional abilities of educational teams and the development of these skills among their students was introduced by Jennings and Greenberg [17]. According to this theoretical model, it is important to first and foremost nurture and develop the skills and abilities of the educational teams to inculcate optimal emotional skills among learners. This idea is based on the understanding that teachers could directly promote the learning and acquisition of SEL skills through the behaviours they demonstrate [13].

2.3. The Framework of the CASEL Model

The broad use of the concept of SEL, the absence of an authoritative definition, and the numerous academic frameworks that emphasise different aspects of SEL indicate the need to create a conceptual infrastructure and accepted standards when discussing this issue. For the current study, and particularly in light of our goals and the characteristics of SEL that were identified inductively in our study, we found the CASEL theoretical model to be particularly suitable, as it comprehensively presents core SEL skills that are integral to the work of educators. Research-wise, we relied on the theoretical framework of CASEL since it was empirically examined and found to be effective [18].

The CASEL model addresses five major interlinked realms of SEL, the process through which all people understand and manage their emotions, set positive goals, and act to obtain them. The five linked realms of SEL according to the CASEL model are as follows. Self-awareness: an individual’s ability to identify one’s own emotions, thoughts, and values and the way they affect one’s behaviour; self-management: an individual’s ability to regulate one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviours in a variety of situations; social awareness: the ability to understand social and moral norms of behaviour, and identify resources in one’s family, school, and community and rely on them. This realm also includes cultivating an appreciation for variety and difference, respect towards others, listening, sensitivity, and empathy towards others’ feelings [19]; relationship skills: an individual’s ability to create and maintain healthy and reciprocal relationships with others from a variety of sociocultural groups, resist negative social pressures, manage conflict, assist others and ask for assistance; responsible decision making: an individual’s ability to make choices that are informed, moral, and effective as regards interpersonal and social interactions. Skills in this realm include, among other things, problem-solving, reflection, and moral responsibility.

A review of the existing literature from a discipline-specific perspective reveals two separate areas in which knowledge on the use of SEL is lacking. First, there is a lack of sufficient disciplinary knowledge about using SEL in teaching literature, a humane field in which the importance of SEL is immanent. Although there are established bodies of knowledge regarding SEL in other disciplines, such as special education [20], in the field of literature, this knowledge is just beginning to emerge. Moreover, while SEL implementation requires a holistic teaching and learning process, most of the professional literature regarding the teaching of literature focuses on the learners’ perspective without addressing the teachers’ perspective [21,22]. Finally, literature teaching—like any effort to make sense of the human experience [23]—has the potential to promote SEL [24]; however, surprisingly, the use of SEL in literature teaching has not yet been thoroughly researched [8].

The second area stems from the learning setting and the understanding that the little knowledge available about the use of SEL in literature is focused on face-to-face learning. However, in recent years, and especially since the outbreak of COVID-19, online learning has become a growing trend. For example, a study from 2012 found that using SEL practices in literature lessons enhances students’ motivation and understanding of the content knowledge [22]. This is an important finding, but as the study focused only on face-to-face learning, it underscores the need to address the issue of SEL in online literature teaching [25]. Lotan and Miller [26] examined signs of innovation in integrating technology into literature lessons, but their study similarly ignored non-face-to-face learning. Finally, even in studies that examined curricular knowledge in literature [27,28,29], the SEL aspect was absent, and again, the online framework of the literature lesson was not taken into account. It appears that the pedagogical potential of SEL has rarely been investigated in the digital environment concerning teaching literature.

Although there are no studies comparing online literature learning with face-to-face literature learning, other studies have identified the major differences between online learning and face-to-face learning. More specifically, in terms of SEL-related aspects, the learners’ interaction [30] and the role of emotion within the learning processes [31] were found to be crucial for conducting optimal online learning; hence, promoting our understanding of how SEL occurs in online literature classes is crucial. The aim of the current study was to address this lacuna by identifying SEL practices mentioned by both lecturers and PSTs as they reported on their respective experiences of teaching and learning in online literature lessons. Considering these two perspectives is important for deepening our understanding of online teaching, learning from a two-dimensional outlook, and providing important insight for advancing literature teaching and learning online. Thus, the following research questions guided the current study:

- How do both PSTs and lecturers perceive their experiences of online literature lessons in terms of opportunities and obstacles?

- What can be learnt from their reports regarding the unique use and role of SEL practices in literature lessons taught and attended online?

3. Methodology

3.1. The Research Context

The focus of this study was on SEL practices that advance online literature teaching and learning, based on descriptions provided by both PSTs and lecturers from four different teacher education colleges about their experiences of online literature teaching and learning. The study was conducted during COVID-19 when online learning became the only viable option.

3.2. The Research Approach

To identify SEL practices that learners and teachers of literature described as part of their experiences of online lessons, a qualitative multiple case-study approach was deemed effective. This approach allows the researcher to analyse the data both within each case separately and across all of the cases, which leads to a comprehensive understanding of the topic [32].

In this study, the experience of online learning and teaching of literature constituted the context that was identical across all of the cases observed. The cases differed in that they were attended by PSTs at various stages of the training programme and were taught by different lecturers at four teacher education colleges.

We selected the interpretive–constructivist research approach [33], which focuses on the participants, their descriptions, and their interpretations [34]. Accordingly, theoretical concepts were developed inductively from the research context [35,36].

3.3. Participants

Ninety students and 28 lecturers from four different teacher education colleges in Israel participated in the study. The rationale for choosing these four colleges was driven by the fact that they represent a broad academic cross-section that includes PSTs and lecturers from both the centre and the periphery and from all subgroups of Israel’s multicultural society. Specifically, the study population included Jewish (75% among PSTs; 93% among lecturers) and Muslim participants (25% among PSTs; 7% among lecturers), from both religious and secular backgrounds, as well as from the geographic central metropolitan area (35% among PSTs; 15% among lecturers) and the geographic periphery (65% among PSTs; 85% among lecturers). As no differences were found between the participants in relation to their demographic characteristics, these are not reported in the Results section; however, we note that the demographic characteristics reflect the diversity of the sample in this study.

3.4. Data Collection

To achieve trustworthiness, we incorporated the strategy of data collection triangulation using the following tools.

Anonymous questionnaires, which were distributed to PSTs and lecturers via email at midsemester, when the system was initially transitioning to online learning. In the open-ended questionnaire, participants were asked to share insight they had gained from the experience of learning/teaching literature online, describe a positive and negative case of an online literature lesson, and share their feelings and thoughts regarding the issue of learning/teaching literature online from any perspective they saw fit (overall, 118 responses were submitted by 90 PSTs and 28 lecturers, each of which was approximately half a page in length).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 12 of the 90 PSTs at the end of the semester over the ZOOM platform. Three PSTs from four of the colleges were selected randomly for the interviews. Several questions were asked to learn more about the PSTs’ perspectives regarding the practices they considered crucial for use in literature lessons in general and in online literature lessons in particular. We developed two questions based on the “big questions” [37]: (1) What do you like about literature lessons? (2) What aspects do you believe are crucial for students attending an online literature course? The interviewees were occasionally requested to go into further detail on particular subjects (often referred to as “small questions”), such as the format of the lessons or their opinions regarding the pedagogical strategies that were employed. Before conducting the interviews, two colleagues, experts in qualitative research and especially in semi-structured interviews, reviewed the interview questions outlined for the current study. The semi-structured interview framework afforded the PSTs enough time to think over their answers and openly voice their opinions [38]. Each interview lasted about 45 min and was audio-taped and then transcribed.

A focus group was held with six of the 28 lecturers (one or two from each college, with three of them teaching at more than one college; total representation of four colleges) at the end of the semester over the ZOOM platform. The lecturers were asked to share the opportunities and obstacles they experienced in their online literature lessons. The questions that guided the focus group were as follows: (1) What are the opportunities and challenges you identify in teaching literature online? and (2) How do you deal with those opportunities and challenges in your lessons? The focus group lasted about 45 min and was audio-taped and then transcribed.

3.5. Data Analysis

Given that the study’s approach focused on the participants, their descriptions, and the interpretations they offered, the data from the three sources were analysed using the interpretive–constructivist research approach and in accordance with the thematic–cognitive method. The analysis comprised several stages, from which meaningful distinctions and generalisations could be drawn [39]. According to Shkedi [40], we analysed the data through the following stages. First, all the data were reviewed by each researcher separately to identify statements related to the research questions. Next, the collected statements were read jointly by the researchers, while marking keywords and sentences that conveyed various aspects of the investigated topic. Then, the data were sorted and divided into “meaning units” that are related to the topic. The mapping analysis was the next stage in which the units of meaning were analysed to identify and understand the connections between them. Finally, in the theoretical analysis, we interpreted the descriptive categories to form a theoretical set of categories, allowing a theoretical picture to emerge from the data. The theoretical analysis revealed that the PSTs’ and lecturers’ experiences of online literature lessons and their perceptions of SEL practices could be mapped to the CASEL framework, with one significant change, as will be presented later. Of note, this study was not intended as an evaluation or validation of the CASEL model; rather, in this study we utilised the interpretive–constructivist approach [33], which allows for an inductive analysis of the data. An examination of the themes that emerged led us to propose this theoretical expansion of the CASEL model.

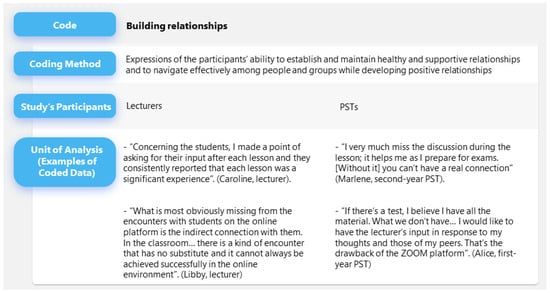

Figure 1 presents the coding procedure by demonstrating the emergence of the theme “Building relationships”.

Figure 1.

A demonstration of the coding process using qualitative content analysis.

The ethics committees of the colleges approved the study. The purpose of the research and the framework in which it would be carried out were made clear to the participants, as was the fact that their participation in the research was completely voluntary. In addition, the participants gave their informed consent after receiving the relevant information about the study and a promise to maintain anonymity and confidentiality (all names indicated in the quotes are pseudonyms).

4. Findings

The data analysis of the three tools revealed six major SEL-related themes mentioned by lecturers and PSTs as essential practices of the online literature lesson. These themes pertain to a set of interrelated cognitive, emotional, and behavioural skills, which can be grouped as one of the key domains of SEL skills, namely, interpersonal skills. Thus, the six themes identified were as follows: building relationships, working collaboratively, emotional involvement, effective communication, dealing with conflicting feelings, and techno-pedagogic skills. Each one of the six SEL-related themes mentioned by the lecturers and the PSTs was related to the research questions. We focussed first on the PSTs’ and lecturers’ perceptions of their experiences of online literature lessons in terms of opportunities and obstacles. Then, we addressed the second research question, namely, the unique use and role of SEL practices in literature lessons taught and attended online. In general, it can be said that the lecturers and the PSTs pointed to the same themes, but while the lecturers considered the experiences of their students, as well as their own, the PSTs often referred not only to their teachers’ experiences and to their own experiences as learners, but also to the experiences of other students. In doing so, they provided an even broader perspective of the online experience. Here, we provide detailed examples and descriptions of each theme, as reported by the study participants.

4.1. PSTs’ and Lecturers’ Perceptions of Their Experiences of Online Literature Lessons, in Terms of Opportunities and Obstacles

4.1.1. Building Relationships

This theme refers to the ability to establish and maintain healthy and supportive relationships and to navigate effectively among people and groups while developing positive relationships. Both the lecturers and PSTs noted this as an inherent part of online literature lessons. In this context, the lecturers referred to the relationships they establish with the learners during the lesson: “Concerning the students, I made a point of asking for their input after each lesson and they consistently reported that each lesson was a significant experience” (Caroline, lecturer). By contrast, the PSTs referred to the relationships with their peers, as well as with the lecturer, and noted that these relationships played a significant role in their learning process.

“If there‘s a test, I believe I have all the material. What we don’t have… I would like to have the lecturer’s input in response to my thoughts and those of my peers. That’s the drawback of the ZOOM platform.”(Alice, first-year PST)

According to Alice, she has access to and presumably understands all the relevant content; however, she assigns importance to the exchange of opinions with her peers and the lecturer as part of the learning process. Another PST noted that the discussion during a lesson creates a connection between the lecturer and the learners in a way that contributes to the learning process: “I very much miss the discussion during the lesson; it helps me as I prepare for exams. [Without it] you can’t have a real connection” (Marlene, second-year PST).

The lecturers communicated a variety of opinions regarding the ability to establish relationships with learners using an online environment. Some found the online platform to be an obstacle.

“What is most obviously missing from the encounters with students on the online platform is the indirect connection with them. In the classroom… there is a kind of encounter that has no substitute and it cannot always be achieved successfully in the online environment.”(Libby, lecturer)

Other lecturers felt that the online platform enabled them to establish a relationship with the learners that is even more significant than that obtained through a face-to-face lesson.

“Personal contact with the learner can occur also in an online course, where you don’t necessarily see the students but correspond with them, right? There are many students that I see for the first time during the exam and then I say to myself that’s who you are… we had extensive correspondence up until now, without ever meeting.”(Avi, lecturer)

It appears that both the learners and the lecturers identify the need to establish relationships as a major conduit of communication in teaching and learning. The discussion, which can be oral or written, constitutes the major means for establishing a relationship in the online environment. This discussion is equivalent to the classroom discussion; however, it appears that opinions vary regarding the quality of the connection established in this environment.

4.1.2. Working Cooperatively

This theme refers to the ability to demonstrate cooperative teamwork. Face-to-face lessons occasionally include cooperative learning tasks as part of the course requirements. Hence, the challenges that the students faced adjusting to online learning were related to both the academic and the social context: “I miss having an interaction with the group, where each person shares an opinion and then ideas are further developed” (Debbie, second-year PST). The academic interaction, according to the PSTs, was related to the social aspect of learning: “I don’t mean only the social aspect, also the learning is affected—the interaction makes me feel that I have something to contribute, that my presence is essential…” (Linda, third-year PST). The PSTs indicated that the cooperation that they experienced in the online environment was different, and that in terms of their social and academic interactions, it presented a noticeable disadvantage.

The lecturers, too, referred to the complexity of working cooperatively using the online platform, but unlike the PSTs, who referred to working cooperatively with their peers, the lecturers emphasised cooperation with their students.

“Teaching is a voyage—a collaborative voyage; it is not mine alone but is shared by us all. I tell my students to think about it as if we were entering the cave and I am holding the flashlight. When we come to a point where the paths diverge, they need to tell me which way to turn. That’s how I imagine our collaboration and that is precisely what is missing in the online learning setting.”(Clara, lecturer)

The metaphor of a voyage, as presented in the quote, illustrates the lecturer’s sense of the need for cooperation in teaching and the challenge of creating a sense of cooperation online. Similarly, other lecturers reported this aspect to be especially challenging in teaching in general and particularly online. Both the lecturers and PSTs mentioned that the teaching and learning of literature using an online platform requires teamwork; the PSTs’ challenge has academic, as well as social implications in terms of their interactions with peers, whereas for the lecturers, the challenge has broader implications given the view of teaching in general as a constructivist activity that relies on teamwork with their students.

4.1.3. Emotional Involvement

This theme refers to the ability to maintain a polyphonic discussion through the development of active listening. In the case of literature teaching, active listening leads to empathy and emotional awareness towards the literary character or situation. Both the PSTs and the lecturers described the need for such a discussion as part of the optimal learning experience and emphasised its importance for creating emotional involvement in the literature lesson. The PSTs claimed that emotional involvement is what makes the teaching of literature different from teaching other disciplines. The lecturers, by contrast, mentioned that teaching strategies that focus on students’ active listening constitute an important component for creating emotional involvement and reported on the challenges of working in the online environment in this context. The following is a quote from Larissa, a third-year PST.

“In literature lessons, it is extremely important to maintain the discussion and enable each participant to express his or her opinion and worldview.… This is unique to the teaching of literature. If there was a way to expand the discussion that can be achieved via the ZOOM platform, many students, including me, would benefit.”

It appears that while the PSTs did not reject the possibility of adjusting the ZOOM platform to allow for a polyphonic discussion that can lead to emotional involvement, the lecturers do not see this as a viable option and, hence, prefer to revert to a face-to-face learning format: “I still think that in face-to-face lessons, small group discussions allow for something extra in the literature class, which elicits an emotional response to the literary work that cannot be achieved in the online environment. It simply not the same” (Maureen, lecturer). This viewpoint was also expressed by additional lecturers.

“Of course, there can be no substitute for personal [face-to-face] contact. I don’t think it would be wise to completely transition from regular lessons to online lessons. Reading the text in the presence of the learners and their processing of the human voice is what leads to their emotional involvement.”(Alicia, lecturer)

This suggests that the role of the teacher in creating learners’ emotional involvement in literature lessons relies on interpersonal skills applied in the context of a polyphonic discussion.

4.1.4. Effective Communication

This theme consists of the participants’ expressions found in the data that referred to the ability to maintain effective communication with others for the advancement of common goals. The PSTs noted the importance of having a direct line of communication with their lecturers, which is insufficient in the online environment: “The ability to communicate directly with the lecturer has a protective role and, unfortunately, its absence in the current environment makes things extremely difficult” (Dave, third-year PST). The lecturers, likewise, noted the difficulty of communicating with students in the online lesson. Specifically, they mentioned that from their perspective, this difficulty had a detrimental effect on their teaching experience:

“When you lecture on ZOOM you have no idea who is with you. You enter one of the break-out rooms and there is awkward silence. You ask a question and wait a long time before anyone responds.”(Roy, lecturer)

The PSTs’ ability to turn off their ZOOM cameras disrupts the lecturer’s ability to maintain constant communication with them during the lesson, which constitutes a complex problem for the lecturer. His use of the plural pronoun “you” suggests that this is a common experience. Thus, it appears that the ability to communicate effectively on the online platform is an essential requirement for the learning and teaching. However, both the lecturers and PSTs noted that this was not achieved and that essentially, the online environment interfered with the possibility of maintaining effective communication.

4.1.5. Dealing with Conflicting Feelings

This theme refers to the ability to deal with conflicting emotions in a positive and constructive manner. Online learning provided both the PSTs and the lecturers with situations in which they had to cope with conflicting emotions. The PSTs felt conflicted about having synchronous online lessons. On the one hand, they found that the excess stimuli (from the platform layout and the non-classroom surroundings) made it difficult to focus on the lesson:

“Focusing in a synchronous online lesson is difficult; I’m busy examining the faces of the participants, of colleagues whom I haven’t seen for a couple of months, instead of focusing on the lecturer.”(Deborah, third-year PST)

On the other hand, both the PSTs and the lecturers realised the importance of conducting and participating in synchronous lessons. Consequently, for some of the learners, this framework created a conflicting situation: although they favoured the synchronous lessons, they found it difficult to concentrate sufficiently during these lessons.

The lecturers experienced conflicting emotions concerning the online environment, particularly regarding their ability to apply familiar teaching strategies to yield optimal results. They noted that they were constantly seeking solutions but were not yet convinced that a significant learning experience could be achieved in the online environment.

“I am missing the element of eye contact: on ZOOM, 40 students appear in miniature and you cannot see their eyes. Personally, I find this difficult. I feel that, besides breaking into a song and dance routine, I am doing everything I conceivably can to address this.”(Clarissa, lecturer)

In other words, the lecturers experienced a lack of a (visual) focus because of the lack of eye contact, which created a conflicting situation vis-à-vis the platform. Clarissa also refers to her difficulty in maintaining the learners’ attention. In other words, her difficulty in the synchronous online lesson is twofold, as she lacked a visual focal point and had to cope simultaneously with the students’ lack of focus. Hence, online literature teaching and learning is a source of conflicting feelings for both lecturers and PSTs.

4.2. The Unique Use and Role of SEL Practices in Literature Lessons Taught and Attended Online

Techno-Pedagogic Skills

This theme refers to the need to cope with technological and pedagogical aspects in the online learning and teaching process. The PSTs noted that the use of the online platform presents a unique difficulty for the technologically challenged, while the technologically literate learners experienced discomfort witnessing their peers’ inability to cope with the technological demands.

“I can manage, but I see others who need assistance in managing the online platform, unable to follow the lecturer’s instructions. You realise that some people are feeling lost and it’s not easy to see. After investing three years in the programme, some people seem like they are about to lose it all.”(Judy, three-year PST)

There is a recognised need for techno-pedagogical assistance, and the difficulty of watching others struggle leads other PSTs to offer their assistance. However, when the lecturers referred to the need for techno-pedagogical assistance, they typically imagine this assistance coming from the college, provided by individuals who are not participants in the classroom. Furthermore, while the online format is favoured by colleges, as it allows for increased enrolment, the increased enrolment means that lecturers need assistance correcting the larger number of academic assignments.

“When there were 15 students per class, I was able to know each one and address their individual needs. With 50 students per online class and seven assignments per semester, you are grateful for assistance although the interpersonal connection is compromised.”(Danny, lecturer)

The implied criticism of the college policy regarding the large number of students enrolled in the class addresses two issues: the difficulty in establishing a personal connection and the difficulty of correcting assignments. Although the college provided a teaching assistant to address the latter, the former remained a palpable difficulty.

As shown, the students addressed both the techno-pedagogical challenges and the resulting emotional difficulty that such an experience produces for the peers of technically challenged learners. The lecturers referred to the technological challenges related to the college policy for online enrolment. In both cases, there was an evident need to address the techno-pedagogical aspects that are uniquely related to online learning and teaching.

To summarise, the analysis revealed six major themes reported by both the lecturers and PSTs as affecting the experience of online learning and the teaching of literature. Only on the theme of building relationships was there some ambivalence regarding its attainment in the online environment; on all the other themes, it was clear that they were difficult to implement in an online lesson, especially in comparison to their implementation in a face-to-face lesson.

5. Discussion

The current findings indicate that the set of SEL skills, which come into play naturally in a face-to-face literature lesson, constitute a major challenge when transitioning the lesson to an online platform, especially when it comes to the need to address techno-pedagogic skills. The challenges were mentioned by the participants as they expanded on the topics of the research questions. The PSTs noted that the online platform challenged their relationships with the lecturers and with fellow PSTs; by comparison, the responses of the lecturers were more ambivalent. Some felt that it was difficult to establish significant relationships with their students, as they were able to do in the face-to-face framework, while others noted the potential to provide significant individual feedback to students within the parameters of the online platform. The fact that both the PSTs and lecturers noted that the online environment does not facilitate the establishment of a polyphonic discussion emphasises the finding of a recent review study, namely, that in online learning, the immediate dialogue that characterises offline learning is lost [41].

The current findings echo those of previous studies, which found that the presence of lecturers in the online setting is related to the students’ satisfaction with the learning outcomes [42]. More specifically, the current study’s findings indicate the diversity of perceptions expressed by both lecturers and PSTs in their assessment of the online learning experience, which was imposed during the pandemic. These and previous findings demonstrate that the online learning as experienced during the pandemic confirmed the existing assumption, i.e., that a well-grounded pedagogical infrastructure is essential for achieving learning goals in the online framework [43,44]. In this vein, the current findings contribute to our understanding of the versatility and complexity inherent in online learning and teaching. The implementation of the new model can help policymakers and educators adjust online teaching and learning to the various needs of both learners and teachers.

The findings of the current study indicate that both lecturers and PSTs experience difficulty applying SEL practices in the realm of interpersonal interactions in the process of teaching and learning literature using an online platform. While the lecturers refer to their students, the PSTs tend to relate their answers to themselves, as well as their fellow students. Consequently, they provided a broader perspective on online experiences. Considering these findings in light of existing theoretical models demonstrates that the five themes revealed here coincide with the set of interpersonal skills included in the CASEL model. However, the sixth theme regarding techno-pedagogical challenges is not part of the CASEL model. In this sense, the findings suggest that the existing model may be expanded to also address online learning in general, as well as techno-pedagogical aspects, in particular. Figure 2 presents the findings of the current study in light of the CASEL model.

Figure 2.

The findings of the current study viewed through the lens of the CASEL model. Note: * The parentheses indicate the original terminology in the CASEL model.

Accordingly, the current study contributes to theoretical and practical knowledge by identifying the need to adapt the existing CASEL model to address the needs of learning and teaching in an online environment. Such an adaptation process would undoubtedly improve the quality of online learning, and, perhaps no less importantly, it could serve to enhance the education and training of teachers by preparing them to operate effectively and optimally in the online environment [45,46]. The themes in the figure emerged from an analysis of the data provided by the participants, who provided these observations in response to the research questions posed in the course of the interviews, the focus group, or in the questionnaire.

The current study also expands our knowledge about SEL in the online environment in general and in the teaching of literature in particular. In this context, it is worth noting that in Israel, where the current study was conducted, the National Academy of Sciences appointed an expert committee to examine ways to further nurture the implementation of SEL in the framework of the education system [13]. Part of the committee’s conclusions was that the discipline of literature is a natural platform for addressing and advancing SEL aspects, such as self-knowledge, acquaintance with the other, the practice of coping emotionally with situations reflected in the literary content, and the principles involved in conducting a mutually respectful dialogue. These assumptions correspond with a broad perspective of the literature as a means to make sense of the human experience [23].

The current study has several limitations. First, the fact that women comprise the majority of the sample could potentially raise the question of the transferability of the study’s conclusions. However, taking into consideration the existing gender imbalance in the field of education, we believe this issue does not impair the transferability of the study’s findings. Second, this study was conducted during a period of intense transformation, driven by the need to educate PSTs in the online environment without the benefit of prior technological literacy preparation [47,48]. However, it was assumed that the triangulation of data collection tools and the use of a multiple case-study framework would serve to enhance the trustworthiness of the findings. Hence, additional studies are needed to examine the issue from a multi-country perspective. Accordingly, we call for additional long-term studies to examine the online learning and teaching of literature and other disciplines in light of the proposed model.

6. Summary

Social–emotional learning (SEL) has received growing attention in recent decades. Although much is known about the benefits of integrating SEL in educational settings, it is important to know more about its practical implementation in online teaching and learning. The CASEL model has been implemented in recent years in many education systems with great success. Nevertheless, to date, empirical studies have examined its effectiveness only in face-to-face teaching settings. The findings of the current study emphasise the need to adapt the model to online learning while taking into account the perspectives of both learners and teachers. The current study’s finding of the sixth theme, which, unlike the other five themes, is not part of the CASEL model, raises the possibility of adjusting and expanding the CASEL model so that it could address the needs of online teaching and learning. From both the PSTs and lecturers’ point of view, it was clear that there is a need to address the unique techno-pedagogical aspects raised from online learning and teaching. In a more general sense, and in line with the five other themes, although both the PSTs and lecturers raised the same themes when referring to the benefits and challenges of online teaching and learning, we can see that the difference between the PSTs and the lectures stems from their point of view. The lecturers referred to their experiences with the learners during the lesson, while the PSTs referred to the experiences with their peers, as well as with the lecturer. In this vein, combining these two perspectives provides an even broader understanding of the online experience of teaching and learning. Although the current findings refer to the online learning and teaching that took place during a period of crisis, we believe they may be relevant to the online framework in general, in times of both crisis and routine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.L. and Y.S.; methodology, O.L.; formal analysis, O.L. and Y.S.; investigation, O.L. and Y.S.; data curation, O.L. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.L. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, O.L. and Y.S.; visualization, O.L.; supervision, O.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Achva Academic College (protocol code 0163, 5 April 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available by contacting the authors and will be provided upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the preservice teachers and the lecturers who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Williamson, B. Psychodata: Disassembling the psychological, economic, and statistical infrastructure of ‘social-emotional learning’. J. Educ. Policy 2021, 36, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amzaleg, M.; Masry-Herzallah, A. Cultural dimensions and skills in the 21st century: The Israeli education system as a case study. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2022, 30, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C.; Flores, M.A. COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, R.P.; Cheung, A.C.; Kim, E.; Xie, C. Effective universal school-based social and emotional learning programs for improving academic achievement: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2018, 25, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePaoli, J.L.; Atwell, M.N.; Bridgeland, J. Ready to Lead: A National Principal Survey on How Social and Emotional Learning Can Prepare Children and Transform Schools; A Report for CASEL; Civic Enterprises: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howells, K. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030: The Future We Want; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zieher, A.K.; Cipriano, C.; Meyer, J.L.; Strambler, M.J. Educators’ implementation and use of social and emotional learning early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.; Broders, J.A. The benefits of using picture books in high school classrooms: A study in two Canadian schools. Teach. Teach. 2022, 28, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.J. What if the doors of every schoolhouse opened to social-emotional learning tomorrow: Reflections on how to feasibly scale up high-quality SEL. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; Kahn, J. The evidence base for how learning happens: A consensus on social, emotional, and academic development. Am. Educ. 2018, 41, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.; Osher, D.; Same, M.R.; Nolan, E.; Benson, D.; Jacobs, N. Identifying, Defining, and Measuring Social and Emotional Competencies; American Institutes for Research: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, O. Emotional, behavioural, and conceptual dimensions of teacher-parent simulations. Teach. Teach. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbenisti, R.; Friedman, T. Cultivating Emotional-Social Learning in the Education System—Summary. The Work of the Committee of Experts, a Snapshot and Recommendations. In Center for Knowledge and Research in Education; The Israeli National Academy of Sciences: Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Israel, 2020. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Kitil, M.J.; Hanson-Peterson, J. To Reach the Students, Teach the Teachers: A National Scan of Teacher Preparation and Social Emotional Learning; A Report Prepared for CASEL; Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Waajid, B.; Garner, P.W.; Owen, J.E. Infusing Social Emotional Learning into the Teacher Education Curriculum. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2013, 5, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.M.; Brush, K.; Ramirez, T.; Mao, Z.X.; Marenus, M.; Wettje, S.; Finney, K.; Raisch, N.; Podoloff, N.; Kahn, J.; et al. Navigating SEL from the Inside out: Looking inside and across 33 Leading SEL Programs; Revised and Expanded Second Edtion; Harvard Graduate School of Education: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, P.A.; Greenberg, M.T. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, K.M.; Tolan, P. Social and emotional learning in adolescence: Testing the CASEL model in a normative sample. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 1170–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Organization. OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030: OECD Learning Compass 2030; A Series of Concept Notes; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Frei-Landau, R.; Avidov-Ungar, O.; Heaysman, O.; Abu-Sareya, A.; Idan, L. Conceptualising Bedouin teachers’ social-emotional learning in the context of teaching children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Teach. Educ. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, O.; Segev, Y. Learning-Teaching Processes in Online Clinical Simulation within Disciplinary Training of Literature. L1-Educ. Stud. Lang. Lit. 2023, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechtman, Z.; Abu Yaman, M. SEL as a component of a literature class to improve relationships, behavior, motivation, and content knowledge. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 49, 546–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corni, F. Stories in physics education. In Frontiers of Fundamental Physics and Physics Education Research; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 385–396. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkman, A.M.; Tofel-Grehl, C.; Searle, K.; MacDonald, B.L. Successes, challenges, and surprises: Teacher reflections on using children’s literature to examine complex social issues in the elementary classroom. Teach. Teach. 2022, 28, 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyas, Y.; Elkad-Lehman, I. Literature through the Classroom Walls: Teaching and Learning Literature in Schools in Israel; The MOFET Institute: Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, 2022. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Lotan, T.; Miller, M. Signs of innovation in the integration of technology in the education of literature teachers. In Teacher Education in the Labyrinths of Innovative Pedagogy; Poyas, Y., Ed.; The MOFET Institute: Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Israel, 2016; pp. 196–227. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bush, L.L. Solitary confinement: Managing relational agent in an online classroom. In Teaching Literature and Language Online; Lancashire, I., Ed.; The Modern Language Association of America: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 290–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T.I.; Elf, N.; Gissel, S.T.; Steffensen, T. Designing and testing a new concept for inquiry-based literature teaching: Design principles, development and adaptation of a large-scale intervention study in Denmark. L1-Educ. Stud. Lang. Lit. 2019, 19, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, O.; Baratz, L. Reading in order to teach reading: Processive literacy as a model for overcoming difficulties. L1-Educ. Stud. Lang. Lit. 2019, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Gu, X. Determining the differences between online and face-to-face student–group interactions in a blended learning course. Internet High. Educ. 2018, 39, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, G.C.; Gutierrez, A.P. The role of emotion in the learning process: Comparisons between online and face-to-face learning settings. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2005; pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. Acts of Meaning; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D.J.; Connelly, F.M. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 1995, 8, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joselson, R. How to Conduct a Qualitative Research Interview: A Relational Approach; Leiblich, E., Translator; The MOFET Institute: Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Israel, 2015. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Leiblich, E.; Zilber, T.; Tuval-Mashiach, R. Seeking and finding: Generalization and differentiation in life stories. Psychology 1995, 5, 84–95. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shkedi, A. Multiple Case Narratives: A Qualitative Approach to Studying Multiple Populations; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Topping, K.J. Advantages and Disadvantages of Online and Face-to-Face Peer Learning in Higher Education: A Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.R.N.; Rosenthal, S.; Sim, Y.J.M.; Lim, Z.Y.; Oh, K.R. Making online learning more satisfying: The effects of online-learning self-efficacy, social presence and content structure. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2021, 30, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.; Lin, T.J.; Lonka, K. Motivating online learning: The challenges of COVID-19 and beyond. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.G.; Cain, M.; Ritchie, J.; Campbell, C.; Davis, S.; Brock, C.; Burke, G.; Coleman, K.; Joosa, E. Surveying and resonating with teacher concerns during COVID-19 pandemic. Teach. Teach. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyment, J.E.; Downing, J.J. Online initial teacher education: A systematic review of the literature. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 48, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, E.; Roussi, C.; Tsermentseli, S.; Menabò, L.; Guarini, A. Teachers’ Self-Efficacy during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece: The Role of Risk Perception and Teachers’ Relationship with Technology. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R. The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 616059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).