Abstract

Physical activity levels among youth have declined globally during the twentieth century. In Japan, the context of this study, this trend is evidenced through decreasing participation rates in school sports bukatsu [extracurricular club activities], where youth participation in sport and physical activity have become a growing concern. Research suggests that incorporating lifestyle sports into the public education curriculum may better align with current youth trends, thereby helping to address these challenges, but little empirical research exist, particularly outside Western contexts. The purpose of this study is to address this gap by offering contextual insights into how the lifestyle sport of surfing is being incorporated into the public education system in Japan, and how this transforms the meanings of both surfing and bukatsu in new and interesting ways. Drawing on the case of Aoshima Junior High School’s Surfing Bukatsu, ethnographic fieldwork was conducted over a two-week period in July 2021 and included participant observation, focus groups with students and parents, and 22 in-depth interviews with various stakeholders. Three themes emerged that guide the interpretation and discussion: (1) a “new collectivism” fostered amongst members of the surfing bukatsu, (2) a “contest(ed) surf style” that marked a tension between the competitive and the informal benefits associated with lifestyle sports, and (3) the role of surfing bukatsu in school/community revitalization. The study shows how incorporating lifestyle sports in PE curricula has the potential to encourage a co-constitutive practice of student/school/community development.

1. Introduction

On 27 July 2021, the first Olympic medals for the sport of surfing were awarded on the sands of Tsurigasaki Beach in Chiba Prefecture, Japan. Standing on the podium were team Japan’s silver medalist Kanoa Igarashi and bronze medal winner Amuro Tsuzuki. Surfing was included alongside skateboarding and bouldering by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in the Tokyo 2020 Games with the aim of attracting a younger audience [1]. In Japan, it was hoped that the Olympics would professionalize the sport of surfing, demonstrating its economic and social contribution, while also legitimizing the role of surfers in broader Japanese society [2,3]. This Olympic-inspired professionalization of surfing in Japan is creating new conditions of possibility for surfing to become institutionalized in new and interesting ways, but empirical research detailing this process is limited.

One important way that surfing is being institutionalized in Japan is through its incorporation in the public educational system. The arrival of lifestyle sports in the Olympics comes at a time when encouraging youth to engage in physical activity has never been more pressing. The World Health Organization [4] reports an increasing prevalence of obesity, prolonged sedentary behavior, and overall declining levels of physical activity among youth. In Japan, research also shows a steady decline in the participation rates in primary and junior high school sports bukatsu [extracurricular school club activities] [5,6,7]. A decline in sports bukatsu participation is particularly concerning as most youth sport and physical activity occurs within Japan’s public education system, with bukatsu playing a central role [5,8,9,10]. In junior high schools, the focus of this study, it was estimated in the 1990s that over 90% of students participated in sports bukatsu (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) 1997; cited in [11]). Recent estimates show a further decrease in participation from 2.33 million in 2009 to 2.00 million in 2018, a drop of 13.1% [7]. Attrition rate estimates over the next few decades are predicting a steady decline in bukatsu participation of around 36% between the baseline year of 2009 and 2048 [7].

The reason for the decline is two-fold. First, diminishing rates of sports bukatsu participation intersects with broader socio-demographic trends in Japan that have seen a reduction in student numbers due to the rapidly declining birth rate. This has resulted in an increasing number of school closures and budget cuts to public education, causing the remaining schools to reduce the variety of sports that are available, or even abolish sport bukatsu activities in the public education system [10]. Second, traditional sporting bukatsu activities—martial arts, baseball, athletics, rugby, and volleyball—are commonly characterized by strict social hierarches between senpai [senior students] and kohai [junior students], and ideologies of perseverance and self-sacrifice developed through long hours of practice and a competitive disposition [10]. The aim of this approach is to develop the spirit and sense of self of students through hard work within a group setting [10]. Consequently, bukatsu have tended to center around a small number of highly dedicated and elite student athletes, which research shows acts as a deterrent for wider participation in contemporary school sports [10].

Outside Japan, the English literature suggests that incorporating lifestyle sports into public education curricula may better align with current youth trends and help to address some of the challenges noted above [12,13,14,15]. However, empirical research on how lifestyle sports are being integrated into a diverse range of public education systems outside Western contexts has yet to be fully explored. Drawing on the example of Aoshima Junior High School’s Surfing Bukatsu, the purpose of this article is to offer contextual insights into how the lifestyle sport of surfing is being incorporated into the Japanese public education system, detailing the strategies of change and continuity as surfing expands and transforms within the bukatsu system. We ask, how do the meanings and experiences of both surfing and bukatsu change when it becomes institutionalized into Japan’s public education system? And what significance is given to the surfing bukatsu in relation to the public education, student well-being, and the local communities in which they are embedded?

To address these questions, this article begins by contextualizing the historical evolution of and current issues facing sports bukatsu activities in Japan. We then examine the literature investigating the role of lifestyle sports in public education systems outside Japan. Next, the research context of Aoshima Junior High School is outlined, and the ethnographic methodology is explained. The findings are then organized into three thematic discussions: (1) “new collectivism”, (2) “contest(ed) surf style”, and (3) “bukatsu in the community”. We conclude by outlining the contribution of this study to the emerging scholarship on lifestyle sports and public education, and suggest areas for future research in this field, specifically for non-Western contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Bukatsu: A Brief History and Current Issues

The relationship between sport and public education in Japan can be traced back to the Edo era (1603–1867). With a focus on fostering samurai philosophy and principles through martial arts [bushido], the purpose of physical education was to purify the mind, develop the spirit, and instill a sense of stoic discipline [5,16]. Taught within private schools affiliated with regional clans or families, sporting practice emphasized control of ones’ mind over technique and the development of Yamato-damashii, a discourse commonly employed to describe an indigenous “Japanese spirit” [17]. The priority given to developing a national spirit through sport continued when imported Western sports like baseball, rugby, football, tennis, and volleyball were introduced during the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912). Sporting institutions positioned Western sports as a “fusion of the values of samurai culture with Victorian values of manliness in the practice of team games” ([18] p. 149). During early Meiji, sports bukatsu became one of the main social institutions for seishin kyoiku, meaning “education of the spirit” [5].

The formation of the sports bukatsu system known today began within Tokyo’s university school system, where Western sports were institutionalized and later spread throughout the country [5,6,8,9]. The integration of sports into the public education system was furthered when Western sport bukatsu were incorporated into high school curriculums, and later, into junior high schools. During the Showa Era (1926–1989), Japan plunged into war. Public resources were directed towards war efforts, referred to as the “total war system”, including those directed towards sports bukatsu, which were also adapted to support war activities [8,9]. Sports bukatsu transformed into a form of auxiliary military training, which Nakazawa refers to as organized “national defense training clubs” [9] (p. 44). This infused military values of masculinity, discipline, perseverance, respect for hierarchy, and group solidarity into sports bukatsu culture [9,19,20]. Following the war, many bukatsu activities came to an abrupt halt as there was no longer time or money to support these club activities [9].

History shows that bukatsu are flexible and served different agendas of the times [5]. Following the war, bukatsu once again transformed to support a new national vision promoting a democracy-based educational reform [9,20]. Instead of teachers giving orders and students simply following them, bukatsu were repurposed to encourage student independence and the enjoyment of sport in an attempt to make sports bukatsu activities more accessible and attractive to a diverse range of students [9]. However, Uchiumi [19] argues that, even during this democratic era, prewar feudalistic principles, wartime nationalistic values, and a continued focus on development of the “Japanese spirit” persisted. Although more inclusive, post-war sports bukatsu remained a site where nationalist values could be maintained within a modernizing public education system and a globalizing Japan [19].

Negotiating this tension between tradition and change, contemporary research on bukatsu and public education focuses on three prevailing themes. First, research has examined the entrenched cultural practice of the senpai–kohai relationship, which establishes a strict social hierarchy by emphasizing respect for seniority, following a chain of command, and group unity over individual outcomes [21,22]. Research shows that the senpai/kohai relationship can foster respect, cooperation, and social bonds between seniors and juniors in an environment more closely resembling the social reality they will experience as working adults, thereby shaping the beliefs and values of youth to align with broader societal norms [22,23]. However, these studies also discuss how a strict social hierarchy and a ‘principle of winning at all costs’ [shori shijoshugi] makes the sports bukatsu experience uncomfortable for many students, acting as a deterrent for broader student engagement. It is also unfortunately common to see news reports of harassment, bullying, and even student suicides caused by problems related to senpai–kohai relationships in bukatsu activities [24].

A second related area of research concerns the effects of bukatsu on students’ mental and physical health. Research shows how a competitive ideology and the ‘spiritual development’ approach to bukatsu creates an environment where excessively long hours of practice, corporal punishment [taibatsu] by coaches, and physical abuses at the hands of the senpai are normalized [10,11,25,26,27,28]. Omi’s [11] survey of university students found that 25% of respondents had been physically punished during their school days, which took place mostly in a bukatsu setting. Of course, research shows that student participation in bukatsu activities can also have a positive impact on academic performance and motivation [27,29]. However, in terms of the impact on students’ mental and physical health, research suggests the way that sports bukatsu has historically developed has led to some notable negative impacts on youth psychological development [27,30] and has become a major social issue that remains under debate [28].

A third area of study has started to focus on bukatsu’s relationship, or lack thereof, with local communities [10,31,32]. Sugimoto et al. [32], for instance, argue that collaboration with local sports bukatsu and non-traditional sports outside of the school grounds could be one strategy for responding to the diverse sporting aspirations of today’s students and lack of school resources [32]. Others suggest that there is a need for a more flexible bukastu system, making it easier for students to participate in wide range of sporting activities by improving their relationships with external coaching systems and allowing multiple schools to collaborate when necessary [10]. Improving the relationships between bukatsu and local stakeholders could be a useful strategy, reconnecting bukatsu with local communities and helping to foster lifelong sports engagement in Japan [10]. This raises some interesting and timely questions that are relevant to this study: How might lifestyle sports like surfing be incorporated into this complex bukatsu history? And are lifestyle sports better positioned to align with a community-based approach to Japan’s bukatsu system, thereby addressing the concerns identified in the previous literature?

2.2. Lifestyle Sports and Public Eductaion

In contrast to Japan’s sports bukatsu activities, lifestyle sports are commonly characterized as informal, individual, and inclusive pursuits with a focus on personal enjoyment, the development of technical prowess, and individual self-improvement [12,33]. Lifestyle sports emerged out of the 1960’s alternative and counter-cultural surfing scene in California, but today comprise a wide range of activities including ocean sports like stand-up paddle boarding (SUP), foiling, windsurfing, and kitesurfing, and land sports such as skateboarding, snowboarding, parkour, freestyle BMX, bouldering, and rock climbing [33,34]. Global participation in lifestyle sports has rapidly increased over the past three decades [12,35,36], and with their inclusion in the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, further institutionalization and expansion into new markets are anticipated [1,2].

As a result, lifestyle sports have become increasingly embedded into national sports systems [1], local public policy and governmental regulation [37], university club activities [38], and, increasingly, into public physical education (PE) programs [12,14,39]. The primary argument for incorporating lifestyle sports into public education is that these activities have the potential to encourage greater participation in sports and physical activity among those who are not actively involved or interested in mainstream school sports [13,14,35]. Lifestyle sports differ from mainstream sports in that they are argued to be inclusive, anti-competitive, less rule-based, have a collegial attitude, and focus on the self-expressiveness of the individual [12,14,35]. Lifestyle sports have increasingly gained acceptance in recent years because they do not place as much pressure on the individual to win, resulting in more positive psychological outcomes [40] and meaningful experiences that promote ongoing engagement and lifelong learning opportunities [41,42]. At a time when the level of physical activity among youth is declining, the inclusion of lifestyle sports in PE curriculums is one possible way to increase physical activity among youth worldwide [12,13].

The inclusion of lifestyle sports in public education around the world has emerged at different times and out of differing social, political, and economic contexts. For example, in Australia, surfing played an important role in liberal education reforms, as far back as the 1960s, which sought to encourage youth self-expression and self-realization [43] (Booth, 2001). This liberal education model would eventually transform into a more professionalized and institutionalized educational practice, with surfing today continuing to play an important part of the school PE curriculum at all levels, including at the national policy level [33] and within the national psyche [43].

In the context of the UK, attention has largely focused on addressing the aforementioned issues of youth obesity and low levels of physical activity, with research exploring lifestyle sports from a pedagogical perspective [12], investigating the UK government’s efforts to promote greater participation in sport and physical activity among youth [13], and examining the physical, mental, and social benefits of incorporating lifestyle sports into the PE curriculum [12,14,35]. Leeder and Beaumont’s [14] study further examines complexities that PE teachers encounter when implementing lifestyle sports, identifying several challenges to the implementation of these activities within the school curriculum, including logistical issues like lack of time, skills and qualifications, funding, and access to resources and facilities. King and Church [13] identified another important benefit of lifestyle sports for PE curricula, which is that they take place in natural and outdoor settings, which has important implications for achieving the UK Government’s goal of encouraging young people to make healthy long-term lifestyle choices.

Lifestyle sport research in East Asia and Japan has only recently started to gain attention [3,34,44,45,46], and to date, investigations into the relationship between lifestyle sports and public education in Japan are rare. There are only a few sporadic examples where schools in Japan have adopted lifestyle sports as a bukatsu activity or have established them as a part of departmental courses. Iwaki Kaisei High School in Fukushima Prefecture incorporated marine leisure and marine sports—including surfing—into its educational content in the 1990s to attract students to the school by promoting the unique coastal resources of the area [47]. Daiichi Gakuin High School, a correspondence/credit high school with schools in Ibaraki and Hyogo, established a skateboard bukatsu in conjunction with the Japan Skateboarding Federation. With a competitive focus, students train to become top athletes under instructors who are professional skateboarders recruited by the school to assist with the lifestyle sports PE curriculum [48]. Other examples include the Japan Surfing Academy High School [49], with schools in Kanagawa and Chiba prefectures, and the Shonan Surfing Academy [50], located in Kanagawa prefecture, where students can earn a high school diploma with a focus on surfing, training them to become professional surfers, surf coaches, judges, and surf industry professionals. Other recent examples include Meisei High School and Kamogawa Reitoku High School, both correspondence schools in Chiba Prefecture, which have established surfing bukatsu [51,52]. Shizuoka Prefectural Sagara High School and Shimoda Municipal Shin-Shimoda Junior High School in Shizuoka Prefecture also have plans to establish surfing bukatsu as a club activity in the near future [53].

Some important preliminary insights can be drawn from the examples above. First, the incorporation of lifestyle sports into the public education system has a strong focus on the professional development of surfers, competitive surfing, and contributing to the surf industry. Second, lifestyle sports bukatsu have previously been and are currently being positioned as a promotional niche for schools to differentiate themselves in the privatized educational marketplace. Lifestyle sports are providing schools with a modern and unique identity, fulfilling hopes of attracting more students at a time when the educational system is suffering from student depopulation, especially in rural regions of Japan. We see an emerging trend of lifestyle sports gradually becoming incorporated into the educational system in Japan, but there is no research examining the meanings and experiences of those involved with these new forms of lifestyle sports bukatsu.

3. Research Context and Methodology

3.1. Aoshima Junior High School: A Rural School in Japan’s Surfing Mecca

Aoshima Junior High School is located in Miyazaki Prefecture of southeastern Kyushu along Japan’s Pacific coast. It is a small fishing village located 20 km south of Miyazaki City and, like many rural communities throughout Japan, is facing significant challenges associated with rapid population decline, an aging community, and a struggling economy [54,55]. Statistical data since 2000 indicate that the population decline is accelerating. The rapid economic development of urban centers during the economic boom in the 1980s led to the depopulation of rural Japan, causing peripheral communities like Aoshima to bear a disproportionate burden of post-industrialization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Aoshima Junior High School, Miyazaki Japan. Photo: Eriko Todaka, September 2019.

Aoshima was not always this way. During the 1960s and 1970s, Aoshima was renowned for being the most popular honeymoon resort destination in Japan. In 1974, a total of 370,000 newly married couples visited Aoshima, representing almost one-third of all married couples in the nation [56]. However, as international travel become more affordable leading into Japan’s economic boom during the 1980s, tourism and economic development in the region were sent into a rapid decline. The three decades that would follow came to be referred to as “the lost decades” [ushinawareta junen] [57]. However, in the 1990s, a new resource for rural revitalization began to emerge in other areas of Miyazaki: surfing [54]. In 1993, the Sheraton Seagaia Resort was opened 40 km north of Aoshima. The mega resort included the Seagaia Ocean Dome, which at the time was the world’s largest indoor surfing wave pool. Between 1991 and 1993, Miyazaki Prefecture would collaborate with the Association of Surfing Professionals (ASP) World Tour, now called the World Surf League (WSL), to host the “Miyazaki Pro” international surf contest, bringing all of the world’s best surfers to the area. Miyazaki came to be referred to as Japan’s “Surfing Mecca” [54]. And although many of these new investments were not directly in Aoshima, the economic and social value of surfing and surf culture was gaining recognition throughout the region. Miyazaki, including the emerging leisure beach culture of Aoshima, is now recognized as being amongst the most popular surf towns in Japan.

Miyazaki’s rich surfing history played an integral role in the establishment of Aoshima Junior High’s surfing bukatsu. The turning point was when the 2019 International Surfing Association (ISA) World Surfing Games were held at Kisakihama Beach in Miyazaki from 7–15 September [58]. The ISA World Surfing Games contributed towards qualification for the surfing event in the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games and included 240 participants from 55 countries. In preliminary interviews with the school administration, it was explained that, as the event was connected to the Olympics, it garnered greater attention from the public than previous surfing events. As a result, the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and the 2019 ISA World Surfing Games helped the sport of surfing become more widely accepted in this small rural community (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Surfscape of Aoshima Junior High School. (Left) surfboard hanging over the entrance. (Right) surfboards drying around the school. Photos: Adam Doering, July 2021.

According to the school principal, students were relocating to other schools to join other bukatsu activities, like basketball (Interview, September 2020). At the time of this study in 2021, the student population of Aoshima Junior High School was extremely low, comprising a total of 51 students: 10 third grade students, 17 in the second grade, and 24 in the first grade. It was decided that the school needed to establish a bukatsu that could embody the uniqueness of the local community, be the pride of the school, prevent the declining number of students, and help revitalize the surrounding community. Shortly after the ISA World Surfing Games, a school survey was conducted amongst the parents and community members to decide which new sport bukatsu could help attract new students to the school. Over 80% of the student and parent respondents replied “surfing”, and in April 2020, one of Japan’s first public junior high school surf bukatsu was established [59].

3.2. Ethnographhic Fieldwork

Leeder and Beaumont [14] suggest that future research on the emerging field of lifestyle sports and public education could benefit from engaging with ethnographic methodologies in a diverse range of contexts to incorporate the multiple voices and perspectives of the stakeholders that are involved. Evers and Doering [34] further argue for more targeted, context-specific, ethnographic insights into the incorporation of lifestyle sports throughout East Asia, which is a diverse region with its own unique histories, interests, needs, desires, and perspectives. This article takes up this call by employing an interpretivist ethnographic approach to offer empirically rich and grounded details regarding the meanings, experiences, and tensions of a diverse range of stakeholders involved in surfing bukatsu activities. An ethnographically inspired approach places emphasis on the importance of cultural and site-specific understandings with respect to the challenges and cultural specificities of incorporating lifestyle sports into the public education systems in non-Western contexts.

Fieldwork was conducted over a period of ten days, from 18 July 2021 to 27 July 2021, with some preliminary interviews with administrative staff being conducted in September 2020. Although brief, as Wheaton [1] argues, even “short ethnographic visits” can provide important insights into the study of lifestyle sports. Ethnographic material was gathered through participant observation, in-depth interviews, and focus groups, both at the school and on the beach. The fieldwork was carried out during the students’ summer holidays and, of the ten days, six were spent practicing in the sea, one day was spent training/studying at school and then going to the beach to practice, and for three days there was no practice. On practice days on the sea, some parents would join the students as supervisors in the water while others watched from the beach. Some of the interviews with the parents took place at this time. The interviews with the students and their advisors were conducted at the school rather than at Aoshima Beach. At the time of the study, the surfing bukatsu comprised 20 students: 10 second year students (3 girls and 7 boys) and 10 first year students (2 girls and 8 boys).

Ethnographic fieldwork was conducted during the summer holidays and 11 students were present at the time of this study. The fact that several students were absent from the surfing bukatsu activities throughout the week demonstrates the informality and flexibility of the club, a key finding discussed later in our findings. In the Japanese context, “school summer holidays” still means going to school every day for practice to prepare for summer competitions. Even during the peak of summer holidays, it is common to see students riding their bikes in the early morning on their way to practice all across Japan. Voluntary absence from practice typically means one cannot join in the competition games. We asked about the absence of some of the students during the week and were told by some that this was because of the flexibility of the surfing bukatsu. Some students involved in activities outside of the school or in collaboration with clubs in other schools (soccer, rhythmic gymnastics) were prioritizing those activities and were allowed to combine these activities. The absence of students does not mean that they were dissatisfied with the surfing bukatsu, but appreciated the flexibility to combine surfing bukatsu with other sporting activities. Therefore, although the limited percentage of student participants is a limitation of the study, it is also demonstrative of the flexibility and informality of the surfing bukatsu, which is extremely rare in the traditional bukatsu system.

A total of 22 people involved in the surfing bukatsu at Aoshima Junior High School were interviewed. This included a wide range of participants including students, parents, principals, advisors, external coaches, sponsors, and residents (see Table 1). All participants helped inform the interpretation of the study but in different ways. As the focus of the research was on understanding the meanings and experiences of participants directly involved in the daily activities of the surfing bukatsu, emphasis and voice was given to students, parents, coaches, and teaching staff experiences. The purpose of interviews with participants who were less-directly involved in the daily operations being represented in the findings (P7, P8, P9, P10) was two-fold. First, these participants are gatekeepers in the community. Note that these are presidents and owners of large hotels and members of indirectly related government agencies. Nevertheless, respect for hierarchy is paramount for conducting research in Japan and entering any field commonly requires talking with influential community members. It was recommended that we talk to these participants to understand their role in helping to start the surfing bukatsu. Secondly, this information was helpful for understanding the context and background of the early emergence of the surfing bukatsu but could not offer detailed insights into the current experiences and meanings as understood by those directly involved in the daily practice.

Table 1.

Study participants.

The interviews lasted between 10 and 90 min, with five interviews using a voice recorder and the other 17 being documented in fieldwork notebooks. As the focus of this study is on sports bukatsu and the participants’ interactions as a group, it was decided that a focus group discussion with the surfing bukatsu students could provide additional insights into the social group dynamics. The focus group took place during the 9th day of fieldwork with 11 students and was conducted in the classroom with students sitting in a circle at their own desks. The focus group was conducted independently by the first author, a young Japanese female university student, and in the Japanese language to create a comfortable environment and make it easier for the group’s collective feelings to emerge [60,61]. The focus group lasted 90 min. The focus group and formal interviews with parents, teachers, and coaches were semi-structured, centering on participants’ meanings and experiences of surfing and bukatsu activities before and after joining the club, previous experiences with bukatsu’s social hierarchies, and current experiences with the surfing bukatsu, surfing competitions, the flexibility of the surfing bukatsu organization, and Aoshima as a place to live and grow up. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

The recorded interviews were transcribed, and all of the fieldwork notes were converted into electronic data. All interviews were conducted in Japanese and translations of the material were made by the authors. The aim of our analysis was to develop an understanding of how the surfing bukatsu was experienced by multiple stakeholders and its meanings for the participants and the community. The process was hermeneutic, inductive, and emergent, with the two authors working in collaboration to co-interpret and co-theorize the surfing bukatsu experience via the ethnographic text, continually discussing and reexamining the data from the field at all stages of the fieldwork process. The ethnographic material was then read and re-read alongside previous research, with the emergent themes confirmed with the adult participants of the study through email and messaging. The final analysis aimed to bring to life the subtle socio-cultural changes and tensions as explained by the participants and interpreted by the researchers. Three prevailing themes emerged from the analysis that form the basis of our ethnographic interpretation of Aoshima Junior High School’s Surfing Bukatsu: new collectivism, contest(ed) surf style, and bukatsu in the community.

4. “New Collectivism”: Reimagining Social Hierarchy in Aoshima’s Surfing Bukastu

The Western literature argues that one of the most important characteristics of lifestyle sports pedagogy is that they are non-competitive and allow for the individual to gain a sense of achievement without competing with other teams or players [12,15,33,35]. This sense of non-competitiveness is the reason that some argue lifestyle sports can be more inclusive for a diverse range of student interests. In contrast, the collectivism of traditional bukatsu activities in Japanese public education is seen as an important tool for socialization in a society where, often, the group takes precedence over the individual [11,62]. From the perspective of public education providers, the importance of buskatsu activities is in fostering a social and collective group dynamic. According to the Japan Sports Agency’s [63] definition in the Courses of Study guidelines, the purpose of bukatsu is “cultivating a sense of solidarity” to develop students’ skills and capabilities within the group life of public education and broader society. Omi [11] describes this approach to bukatsu as a form of “downward collectivism” characterized by the suppression of individual expression and individuality. A tension between these two competing discourses of lifestyle sports and bukatsu was at play in the early development of the surfing bukatsu, but following a difficult first year, a “new collectivism” started to emerge where the individuality, flexibility, and informal comradery that characterize lifestyle sports became incorporated into the collective social hierarchies that have long defined traditional bukatsu.

4.1. Individual and Group Tensions in Lifestyle Sport Bukatsu Activities

The tension between the ideal of surfing as an individual sport and the collective mentality of traditional bukatsu was described in many conversations and interviews. When asked about surfing, parents often emphasized the value of surfing’s individuality, with one parent declaring that “surfing is an individual sport” and another describing it as “quite a solitary sport”. The surfing bukatsu teacher advisor (P4) further reinforced the contrast between surfing and bukatsu activities, explaining that “Surfing is originally an individual sport, so there is a big gap with bukatsu activities”. He continued to explain that, by incorporating surfing into the bukatsu system, the original meaning of surfing as a free, individual, and creative expression was “cut in half”. It was clear that parents, advisors, and teaching staff perceived surfing as an individual pursuit that was not common to traditional bukatsu culture.

This tension surfaced early in the development of the surfing bukatsu. During the club’s first year in 2020, teachers, students and parents alike considered “surfing as an individual sport”, but noted that the public education system is designed to place more emphasis on the collective group dynamic where, as the former principal (P1) described, “all members practice the same thing at the same time and place.” This meant that surfing practice mostly took place in the school swimming pool during the first year, where, unlike the unpredictable and “dangerous” ocean, group activities could be scheduled in advance and completed as a group. The first school principal (P1), who helped found the bukatsu, further explained that surfing is like any other sport bukatsu—tennis, swimming, baseball— and “Even though it is called a surfing bukatsu, it is still a “bukatsu” activity. So we want the students to learn mana [good manners] and reigi [etiquette].” From this perspective, surfing bukastu was still a public educational activity, and as a public official, the goal was to maintain the traditional values of bukatsu activities in the new surfing context.

In interviews with teacher advisors, coaches, teaching staff, and parents, we learned that parents of the more advanced surfers began to question the traditional group-orientation of bukatsu activities. Weekday surfing practice in the pool was not improving anyone’s skills. Tensions began to arise between parents who saw surfing as a more individual pursuit with a focus on self-expression and personal improvement and public officials seeking to maintain the group-oriented nature of bukatsu. The traditional group orientation of bukatsu activities was not aligning well with this new lifestyle sports bukatsu. This tension was eased in 2021, the bukatsu’s second year, with the appointment of a new school principal. Changes in school leadership had a profound impact on the management and social environment of bukatsu activities. Parents and advisors explained that, with new leadership, the bukatsu changed to “a more flexible form of bukatsu activities.” For example, under supervision of their parents, more advanced-level students were allowed to be absent from the group practice days when the waves were better at the other surf breaks in southern Miyazaki. This created a more flexible environment, with parents taking on an important supervisory role in the bukatsu activities. This also allowed the surfing bukatsu to better accommodate the differing skill levels and interests of individual students.

This developed into what we refer to as a “new collectivism”, where a strong sense of group belonging remained while also catering to these individual needs. During the focus group, the advanced surfing students explained that they did not only want to surf alone, as “it’s more fun and exciting to surf together” (P15, P16) (Figure 3). This was echoed in the focus group (P12, P13, P14), with the beginner-level students explaining that they support the individual efforts of the more advanced students. Individual practice based on skill level was seen as a benefit to the group: “We want the good kids to keep going to the good surf points to practice. We want to see them improve too.” Despite catering to individual skill levels and training requirements, a strong sense of group identity and sense of belonging was clear. This marked the beginning of a “new collectivism”, one where the bukatsu is transformed into a more flexible, horizontal organizational culture that includes parent supervision and accommodates for individual needs, while still maintaining a sense of social group cohesion, but, as we will now explore, in non-hierarchal ways.

Figure 3.

Greeting the sea together before practice. Photo: Eriko Todaka, September 2021.

4.2. “There’s No Need for Hierarchy”: Reimagining Senpai–Kohai Relations

Group cohesion in traditional sports bukatsu is commonly defined by a strict social hierarchy. This top-down hierarchical structure of sports bukatsu has been discussed in many studies and news reports about the Japanese public education system [22,24,45]. It is argued that the hierarchical relationship between senpai [senior students] and kohai [junior students] in sports bukatsu activities fosters a domineering and unequal power relationship [64], what Omi [11] refers to as a “downward collectivism” that can repress individual expression. A concern for this traditional bukatsu social hierarchy was expressed by several parents. When asked about their own experiences of bukatsu activities, one parent noted, “In our day, bukatsu was all about senpai and kohai relationships. We had to say hello to the seniors when they passed by. We were afraid of them if we didn’t greet them properly. We were more concerned about our senpai than our teachers” (P3). As another parent put it, “I really didn’t like the military aspect of the bukatsu activities” (P11). Parents expressed that they did not want the same experience for their children, and the surfing bukatsu was understood as a possibility to establish new forms of social relations for their children.

With a new collectivism forming, different kinds of social relations began to emerge. When the surfing bukatsu was founded, there were three third-year students and nine first-year students, a total of 12 members. At that time, none of the third-year students had surfing experience. However, they each had experience in mainstream sports and knew the hierarchal structure of traditional bukatsu. Initially, the teacher advisor also believed that bukatsu activities were a place to learn about hierarchical relationships, and so he instructed the students with this in mind. However, this mode of social hierarchy did not make much sense in the surfing bukatsu, as the third-year students who had never surfed before were supposed to be guiding the first-year students, who were the more experienced surfers. This made the teacher advisor rethink this approach, “I now don’t put too much emphasis on this traditional senpai-kohai relationship. We’re not going to put too much emphasis on hierarchy, because the times are changing” (P4).

When students were asked during the focus groups about the bukatsu social hierarchy, responses included: “There is no seniority.” “There is no hierarchy.” “There is peace.” “If there was hierarchy, the atmosphere would be bad. It wouldn’t be fun.” As one second grade student described, “There is no need for hierarchy. You don’t have to stress about other people [senpai and kohai] like in other bukatsu” (P12). It was clear that the current members of the surfing bukatsu felt that there was no need for this traditional sense of bukatsu social hierarchy. A sentiment echoed by the one parent who commented:

In the surfing bukatsu, it’s not so much about seniority, but more about the kids who are good teaching the kids who are not so good. From what I’ve seen, everyone is pretty relaxed. We used to say hi to our seniors at school because we were afraid them…Now, students admire and respect each other because of their skill. I often hear my son express his admiration for the younger surfers at home, saying things like “XX-kun is good.”(P11)

The reimagining of social relations within the surfing bukatsu was informed in part by the skill level difference between the members, the change in school principal, and the teacher advisor’s change in attitude. By the second year, it became clear that a new collectivism had formed, characterized by the sharing of opinions and skills, collegiality, and cooperation amongst students regardless of their grade level. The organizational structure became more flexible, more supportive of individual needs, and fostered a sense of group belonging based on mutual respect and support for each other’s skills rather than seniority. Participants described the surfing bukatsu as being more inclusive, democratic, and welcoming than both the parents’ and students’ previous experiences of traditional bukatsu.

5. Contest(ed) Surf Style: Negotiating Competitive and Informal Benefits

Incorporating lifestyle sports into traditional bukatsu public education allows for new possibilities and practices of individualization and flexibility, but this focus on individual skill development may also incidentally maintain the priority given to competition found in traditional bukatsu. Otake and Ueda [10] argue that sports bukatsu activities have a long history of being competitive sports between schools, to the extent that it is generally assumed that sports bukatsu activities are synonymous with competition. The benefits of self-development and fostering group cohesion and school pride are said to derive from this competition-based approach. In contrast, English research suggests that the benefits and opportunities associated with incorporating lifestyle sports into public education come from their non-competitive, informal, and inclusive structure [12,13,35,36]. Debates concerning the intrinsic and external value of competition also form the foundation of the philosophy of sport, examining the pursuit of victory or the pursuit of excellence as a desirable aim or outcome of sporting competition [65,66]. The philosophy of sport, therefore, asks us to reflect on the meanings of “sport” itself. However, the constructivist paradigm taken up in this study takes a pluralist approach to meaning-making, understanding that sport culture is emergent rather than fixed, with meanings being negotiated from the socio-cultural and historical situatedness of a given sport in a particular context [67]. What follows is an analysis of the meaning-making of “competition” as the lifestyle sport of surfing intersects with the history and social setting of competition within the bukatsu experience.

In the interviews, an importance placed on establishing surfing bukatsu competitions was apparent, with several of the study participants placing a strong emphasis on building the junior high school surfing competitions into a national competition. This raises a concern that placing too much emphasis on surfing bukatsu competitions may, in the long-term, undermine the benefits attributed to lifestyle sports which have been identified in previous literature. The aim here is not to judge whether surfing competition is “good” or “bad”. Rather, the purpose of discussing the emergence of a contest(ed) surf style is to contextualize the historical role of competition in sports bukatsu, identify how competition is currently being discussed in the surfing bukatsu, and to contrast this with the student well-being benefits as pointed out in the literature and described by some participants themselves.

5.1. “Winning at All Costs” [Shori Shijoshugi]: Bukatsu and the Growth of Competitive Surfing

The competitive ideology of “winning at all costs” [shori shijoshugi] has been an important point of debate in the literature on sports bukatsu activities, attracting attention not only in academic circles [10,19,22,27] but also in the mass media (e.g., [68,69,70]). Early research in the field by Imahashi et al. [71] points out that the competitive nature of bukatsu activities has led to injuries as well as overall health and well-being concerns among students. As Tomozoe [20] argues, some schools even prioritize bukatsu activities over schoolwork, and until the 1960s, strict standards had to be set for inter-school competitions to help manage this “winning at all costs” attitude. However, due to the declining birth rate in recent years, there has been a shifting trend towards co-opting bukatsu activities and success in competitions as a promotional tool, demonstrating the attractiveness of a given school in an increasingly competitive educational marketplace [20,22]. In this way, bukatsu continues to play an important role in school promotion and attracting students, but the winning-at-all-costs attitude still casts a shadow over the bukatsu system [20,22]. Our interviews reveal that the surfing bukatsu at Aoshima Junior High School also seeks to maintain this competitive bukatsu framework, although, currently, in a much less serious manner than the conventional “winning-at-all-costs” approach.

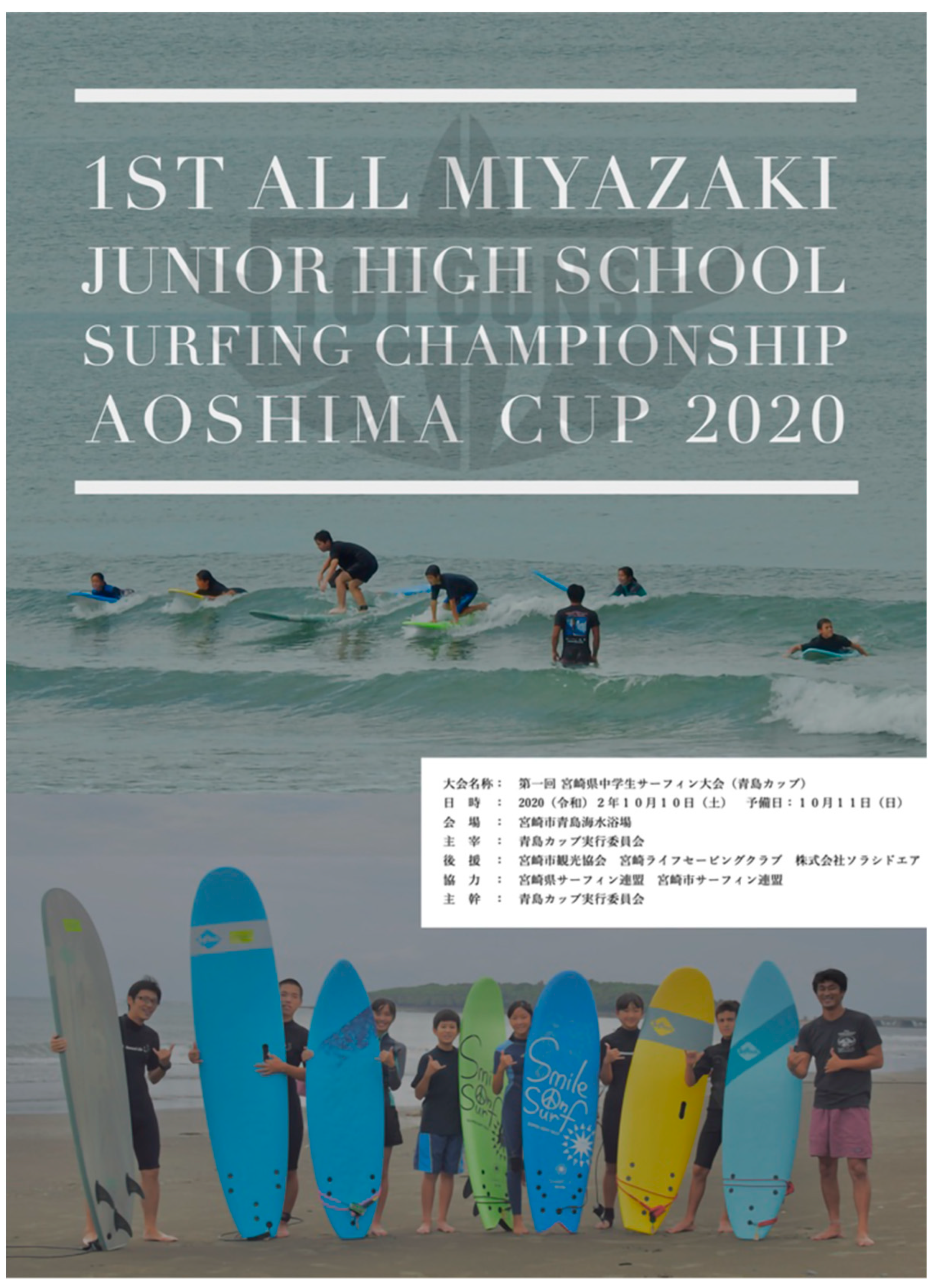

On 10–11 October 2020, the first “All Miyazaki Junior High School Surfing Competition: Aoshima Cup 2020” was held (Figure 4). Hosted and organized by the Aoshima Junior High School Surfing Bukatsu, the competition was open to all junior high school students in Miyazaki Prefecture and attracted a total of 28 participants. Thirteen competitors were from outside of Aoshima Junior High School.

Figure 4.

Flyer of the first “Aoshima Cup” [72].

As the fieldwork took place at the end of September, there was a buzz in the air about the upcoming competition. Teaching advisors, surf coaches, parents, and the school principal each explained how they considered competition to be an important tool to keep students motivated and challenging themselves through bukatsu activities. As the father of one of the advanced-level students described it, “I think the surfing competition has given the kids a lot of motivation” (P6). This was echoed by the teacher advisor who commented, “I felt it was important to have a tournament or a place where everyone can see how much they have improved and show their achievements” (P4). The external advisor and surf coach outlined the future goals of the surf club, stating, “We want to hold more competitions. I want to give the students the experience of winning as a team” (P5). On the day of the competition, we wrote to see how the event was going, with one father responding,

Everyone is buzzing about it. Hopefully it’ll grow and get bigger every year. The waves were actually pretty good for the contest and offered something for all the different levels. It was on the local MRT news last night…I think the kids all enjoyed themselves.(P6)

The discourse of a need to develop and expand the competitive aspects of the surfing bukatsu reminded us of the first interview with the former principal a year earlier (P1). The former principal explained that surfing is not a mainstream sport in Japan and that if they hoped to make the surfing bukatsu a “success”, they needed to figure out what competition was needed to make it a major sport in Japan. According to the principal, the final goal would culminate in establishing an all-Japan surf competition in collaboration with the Nippon Surfing Association (NSA). The Aoshima Cup is one small step towards a larger path of increasing the professionalization and institutionalization of the sport as anticipated by the former principal. In the short term, the findings show that both parents and coaches saw the competitive aspects of surfing as important for keeping students motivated throughout their bukatsu activities. In the long run, however, one can also understand this process as a slow movement towards an increasing focus on competition, which could possibly lead towards the competitive disposition that has characterized more traditional approaches to bukatsu.

5.2. Creating a Space to “Be at Ease”: Maintaining the Benefits of an Informal Surf Bukatsu

Tomozoe [20] argues that the benefits of bukatsu activities should not only focus on competition, as bukatsu also represents a significant space where students can feel at ease in the world and society—referred to as ibasho, meaning a place where one can be at ease. In the interviews, the teacher advisor [komon] (P4) explained how this sense of being-at-ease was described by some students, in that the surfing bukatsu “…is a culture, not a competition or anything. We do it because it’s fun to ride waves with everyone. It’s good if they can surf with everyone and just have fun.” This sense of “just having fun” and “being-at-ease” was also described as having a positive effect on the physical and mental health of their children. One mother of a first-year student (P3) explained that her child’s mental state had improved since joining the surfing bukatsu. The sense of freedom from competition, and the informal structure of “just” being with friends—unstructured social interaction—is something that many students valued. This was nowhere more evident than when we would join the surf practices and witness students smiling, laughing, and just playing together in the sea.

The discussion above echoes the sentiments of the emerging literature on the mental, physical, and social well-being benefits of routine engagements with blue spaces, including being in the sea and surfing [73,74,75]. Britton and Foley [73] explored the connection between social practices and place in how people experience immersion in natural blue spaces, arguing that surfing can open new spaces for people to be different in the water than they are on land, a place to be-at-ease with themselves. Testimonies were described by the teacher advisor (P4) who poetically explained, “Even though they are sidewinds in their everyday lives, the students become pure children when they enter the ocean.” Another father (P6) explained, “Surfing makes him feel alive and stress-free every day. There is no ‘crazy teenager’ type thing, no frustration at all”. In terms of competition, one mother (P2) said, “Surfing is a sport whose aite [partner, opponent, companion] is nature, so his mind is getting stronger”. Students described the intrinsic motivation offered by the informal character of the surfing bukatsu, with one advanced-level student (P15) explaining, “Surfing heals me, it puts me in a good mood even when I am upset. Surfing refreshes you and motivates you to do more”. Again, “just” having a space and place for students to be at ease was itself an intrinsic motivating factor.

Exceptional stories of the informal benefits of the surfing bukatsu during the COVID-19 era were also reported. One family (P3) decided to move to Aoshima from outside the prefecture in April 2021. At the elementary school they attended in Osaka, strict regulations were imposed due to the outbreak of the new coronavirus, and children were forbidden to play in nearby parks or with other children. They were even reported to the school if they were found gathering. The stress of these days led to a gradual decrease in speaking and communication by the child, an increase in gray hair, and only being able to eat certain foods due to the stress. However, after moving to Aoshima and joining the surfing bukastu, the child’s stress and symptoms soon stopped. The parents said, “The feeling of liberation for my child in Miyazaki is amazing”. These parents were amongst the most vocal in arguing for maintaining a sense of informality, personal expression, and flexibility in the bukatsu, a sentiment echoed by others in the study but which was, at times, contradicted by the push towards a more competition-focused future for the surfing bukatsu.

6. Surfing Bukastu and School/Community Revitalization

For Aoshima’s surfing bukatsu to be successful, the public education system had to find new and interesting ways to connect with the community. In fact, engaging with the community was more of a necessity than an option, as the surfing bukatsu would not be possible without close community engagement. Community involvement was central to the formation of the surfing bukatsu, which in turn not only helped with the revitalization of the school but also became implicated in the wider rural regional revitalization efforts. In this way, the multiple and varied institutions and relationships that assembled around the surfing bukatsu led to a co-constitutive dynamic where lifestyle sports, lifestyle mobilities, and public education systems intersected and reinforced one another. In this Section 8, we examine the new and emerging connections between the surfing bukatsu, the local community, businesses, and the natural environment to show the necessity of community engagement for the incorporation of lifestyle sports into public education and the social outcomes that this generates within the Japanese context.

6.1. Community Engagement as Neccesity to Incorporating Lifestyle Sports into Bukatsu

During the second year, the daily practices moved from the controlled environment of the school’s swimming pool to the sea. To relocate outside of school boundaries required new engagements and connections with the local community. At the time of the study, no teaching staff had experience surfing or training in water safety. To ensure the safety of surfing bukatsu members and to develop practical skills, external advisors and surf coaches familiar with surfing and ocean safety were necessary. The organizational structure of the surfing bukatsu was like other sports bukatsu in that it was directed by a teaching advisor [komon] and deputy advisor [sub-komon], who are employed as educational staff within the school. However, as the teaching staff had no previous surfing experience, all the technical aspects of surfing needed to be taught by the external advisor/surf coach (P5), and at times the fathers of students.

The external advisor/surf coach was from Miyazaki City, and a qualified lifesaver who worked as a part time lifesaver at the Nagisa-no-Koban [Seaside Patrol Station]. The external advisor is a respected big-wave surfer in Japan, and due to his close engagement with the local community’s beach activities, many of the bukatsu participants noted they had admired him even before joining the club. For the surfing community in Aoshima, having the external advisor gain stable and professional employment as a surf instructor within the public education system was considered a significant step towards legitimizing the role of surfers in the broader community. No longer perceived by the public as a problematic sub-culture, young surfers are now training as athletes and surfers have become public educators. Surfing has moved from an alternative periphery to Aoshima’s community core. As the surf coach explained, the surfing bukatsu “cannot be completed only with in the school or using school resources” and that “the support of the community and people from outside the school is necessary and has been very strong.” Close engagement with the community was considered a necessity, especially from a public education human resource perspective. Lifestyle sports may find new ways to connect PE curriculums to the community as identified in the previous literature, but in this case, community involvement was a foundational part of its incorporation.

Positioning surf bukatsu within the mainstream sporting culture and as an important tool of community revitalization in Aoshima has created new relationships with a variety of groups. Businesses were enthusiastically supportive of this effort. The Aoshima Grand Hotel, located near Aoshima Beach, provided parking, shower facilities, and shade for the Aoshima Junior High School Surfing Club during their practice times in the sea and for competitions. There were also donations of surfboards and wetsuits from nearby surf shops. Solaseed Air, an airline company based in Miyazaki, donated surfboards and wetsuits to the club as part of its corporate strategy to support rural revitalization in the region (Figure 5). Solaseed Air offered lessons for students by professional surfers who were sponsored by the company [76,77]. Spiritual reconnection was also encouraged when Nojima Shrine, located near the school, gifted omamori [amulets] made at the shrine to pray for the students’ safety at sea (Figure 5). The presence of the surfing bukatsu acted as a hub for different kinds of community members to come together: public education, business, local shops, and shrines gathering in support of the students.

Figure 5.

(Left) omamori [amulet] gifted by Nojima Shrine to the surfing bukatsu. (Right) surfboards donated by Solaseed Air. Photo: Adam Doering, September 2021.

Students found themselves connected to their community, school, and the sea in new and interesting ways. As the advisor put it, “The surf club is made up of people from the community. It is not like a traditional bukatsu activity because it cannot be completed within the school organization, only using the school resources.” Lifestyle sports are considered difficult to incorporate within the school curriculum, but from this broader community perspective, lifestyle sports can strengthen ties with a wide variety of members from the community.

6.2. School and Community Building: Bukatsu, Lifestyle Migration, and Place Attachment

During the first interview with the principal of the school (P1) in 2020, a new phrase was introduced that has been under-recognised in the lifestyle sport context, gakko tzukuri. Roughly translated as “school revitalization”, the phrase derives from the more common term machi tzukuri, which refers to community revitalization and is a key discourse in rural redevelopment in contemporary Japan. Like many rural regions, Miyazaki City is faced with the challenge of a declining population and has sought to address this issue by offering support for a variety of lifestyle migrants to move to the area [78]. School revitalization is considered part of the process of creating a public education system that is more accessible to the local community by working with government officials, migration departments, families, and residents to improve the overall learning environment for children’s development [7]. Within this context, the surfing bukatsu is considered a “community club activity” with the aim of fostering an attachment to the local environment, attracting new migrants to the region, and providing more opportunities to deepen cooperation with local businesses and residents. News reports suggest that bukatsu activities that make use of local resources have helped halt the declining student numbers [59]. Likewise, the surfing bukatsu was seen as part of this broader community revitalization project. Revitalizing the school [gakko tzukuri] was considered an important element of this broader social movement, with the surfing bukatsu acting as the focal point to attract young families to this rural area.

We spoke to one family who moved to Miyazaki in April 2020, its inaugural year, to join the surfing bukatsu at Aoshima Junior High School. They chose to move to Aoshima, a city they had visited several times on holiday, to fulfil their child’s wish to be near the sea and join the surfing club. His parents noted that, before moving to Aoshima, their child was having difficulties interacting with others, but after the move he started to become more outgoing. The surfing bukatsu at Aoshima Junior High School was an important factor in the decision to move. Already in its first year of existence, the bukatsu was attracting young families to the area, creating ties between the students and the environment, and creating new opportunities to attract new young people to this depopulated rural area.

Recent trends in higher education and employment for high school and university students in Miyazaki Prefecture in 2018 indicate that, although the in-prefecture employment rate for high school graduates is gradually improving, about half of the 10,000 graduates move out of the prefecture for higher education or employment [79]. In addition, the employment rate for university graduates in the prefecture is only around 40%, so there are very few young people who stay in the prefecture or come back to the prefecture. We asked about this issue during the focus group with second-year students, discussing what they liked about living in Aoshima and how they thought about staying or moving out of the prefecture in the future. Although one student was considering moving out of the prefecture for higher education, the rest of the students said that they would like to have a home to come back to even if they moved away.

The fact that Aoshima Junior High School is located about 3 km from the sea, easily accessible and always present in their lives, was a memorable feature of school life in Aoshima. As one student simply and powerfully stated, “The best thing about Aoshima is that it is close to the ocean…we have always had the habit of playing in the ocean since we were little kids.” King and Church [13] suggest that conducting lifestyle sports in rural, nature-rich spaces may further enhance the bonds of participants with their place. This was evident in the study, as the students of the surfing bukatsu were familiar with Aoshima beach, having made it a part of their lives from an early age. Joining the surfing bukatsu deepened their relationship with the sea through connections with others. The relationships and sense of community built around the sea made possible through the surfing bukatsu were a significant part of their experience, as one student explained: “I am happy to go to the sea in Aoshima because I can meet so many different people from the local community” (P14). The students expressed a feeling of being cared for, of the community supporting their learning experience, and of being an integral part of the community. The surfing bukatsu was, therefore, not only about establishing a relationship with the sea, but also about how the sea connects people and, consequently, connects students to their place. Several students expressed that, even if they must leave Aoshima in the future for higher education or job opportunities, they still wish to return one day. As one student described, “Even if I leave Aoshima, I want to have a home to come back to. I’ll always come back” (P12). A statement that was followed by another student who echoed, “We have Aoshima in our hearts” (P13).

7. Discussion: Lifestyle Sports, Bukatsu and Emergent Sporting Culture in Japan

In their overview of lifestyle sports for the future of PE curriculums, Beaumont and Warburton [12] suggest that what is needed today is a redesigning of what PE means for students, parents, teachers, schools, and society, taking more seriously the perspective of young people and how they give new meanings to their PE experiences. In the field of lifestyle sports more generally, Evers and Doering [34] argue that, as lifestyle sports gain attention and are increasingly institutionalized throughout East Asia, it is also important to pay attention to the specific cultural politics, unique contexts and histories, differing structures and institutions, and emerging needs and desires of non-Western contexts. Drawing on the example of Aoshima Junior High School’s Surfing Bukatsu, this article offers a rich contextual contribution by offering insights into how the lifestyle sport of surfing is currently being incorporated into the Japanese public education system and the emergent meanings given to both surfing and the bukatsu educational system. Detailing the changes and continuities as the new sport of surfing and traditional bukatsu system converge, we examined the currently unfolding “redesigning” of Japan’s PE programs through lifestyle sports, with a focus on the shifting meanings of social hierarchy, competition, and community within the bukatsu system.

First, through this study, we see how the incorporation of lifestyle sports into Japan’s PE program has helped reimagine entrenched ideas of social hierarchy that have long defined the bukatsu system. This was a social structure defined by the senpai/kohai relationship, emphasizing respect for seniority, following a chain of command, and favoring group unity over individual outcomes [21,22]. Research suggests that this “downward collectivism” may lead to notable negative impacts on youth psychological development, resulting in considerable social debate on how to make bukatsu more inclusive [11,22,28]. To this end, the incorporation of surfing into this traditional bukastu system has opened new spaces of negotiation for these conventional social relations. In the first year of the surfing bukatsu, the intention of the school principal was to align the club with the Ministry’s principle aim of fostering a sense of group solidarity by maintaining traditional senpai–kohai social relations and providing top-down control over the surfing space and place through regular scheduled practice times in the school’s swimming pool. Over the year, it became clear that the conventional organization and social hierarchies did not align well with the surf bukatsu, or the students hopes and desires. Following concerns from parents and students, and a change in the head principal, the second year of the surfing bukastu saw a transformation into a more flexible form of bukastu activity, where advanced students were allowed to take time off from scheduled group practice for individual training with the guidance of their parents. This also loosened the conventional social hierarchies between senpai and kohai, as well as altering the teaching advisors’ ideas of students’ guidance and governance. A “new collectivism” was formed.

New meanings of group unity and collectivism were fostered based on mutual respect, personal choice, self-autonomy, and the recognition of individual differences in needs and desires. The “new collectivism” was described as more horizontal—side-by-side—than downward in terms of social structure, more flexible in terms of the club’s organization and operation, and catering more to each students’ individual needs than giving priority to the group. Social interaction, identity development, and reinforcing the connection between youth and their local environments were some of the expressed outcomes of these changes. The support by the students, parents, and educational staff for reorganizing the surfing bukatsu in this way supports previous research suggesting that lifestyle sports may better align with the changing interests of today’s youth (and parents), its potential to be more inclusive, and that social benefits for students can be derived from such sporting activities [12,36,42]. For readers unfamiliar with Japan, such changes may appear minor, but those familiar with the bukatsu system understand these to be significant transformations of the bukatsu educational system with potential implications for society more broadly if adopted more widely. We argue that changes to the PE curriculum enabled through lifestyle sports can also transform social relations as youth move forward into their careers and adulthood.

Second, the article raised concerns about the role of competition as lifestyle sports become increasingly incorporated into the PE systems in Japan and potentially abroad. Research suggests that the informal and non-competitive character of lifestyle sports helps to foster the physical, psychological, and social benefits associated with their incorporation into PE curriculums [12,14]. However, the case of the surfing bukatsu within the Japanese context shows how maintaining an informal, flexible, and non-competitive approach may prove difficult as the powerful sporting and educational institutions seek to maintain an historically embedded competitive approach, which aligns with the global and Olympic agenda of the growth, expansionism, and professionalization of lifestyle sports in Japan and around the world.

This study revealed a possible future tension between the suggested benefits of an informal approach to lifestyle sports in PE curricula and the competitive disposition of traditional bukatsu activities. Several of the interviewees emphasized the importance of developing and expanding on the surfing bukatsu competition, even expressing a desire to make it a national competition and thereby legitimizing the surfing bukatsu as a “real sport”. Parents of the advanced students, the former principal, the surf coaches, and the teacher advisors saw the competitive component as an important motivator to students. Competition was also considered an important tool for the promotion of the surfing bukatsu and, consequently, promotion of the school [gakko tzukuri] to help attract more students. Yet, others described surfing activities as part of a new school culture and engaged in bukatsu activities with a spirit of “just having fun”. In these descriptions, the most fundamental benefit of this surf space was that it allowed students to “be-at-ease” with themselves, with nature, and in society. The sense of being free from competition, hierarchy, seniority, strict rules, and simply enjoying the company of friends, sharing time, and being together in the sea was something that many students valued. Parents and advisors also noted that the informal aspects of the surfing bukatsu had a positive impact on the students’ physical and mental well-being. Placing too much emphasis on competition could potentially diminish the expressed benefits that an informal approach to lifestyle sports offers students.

To be clear, the surfing bukatsu at Aoshima is currently not defined by a domineering competitive attitude. Moreover, competition itself is not inherently a bad thing. However, the ideologies of perseverance, long practice hours, strict social hierarchies, and corporeal punishment that come along with traditional competitive bukatsu create conditions that may evolve into a more competitive structure for the surfing bukatsu in the future. If social practices, institutions, ideologies, and power structures that surround the newly forming surfing bukatsu remain within a traditional competitive framework, it is difficult to imagine a situation where the increase in competition would not lead to a similar structure of other bukatsu activities. This could even be the most likely outcome as more and more schools across Japan establish surfing bukatsu and competition to attract students intensifies. Competitive surfing is becoming a marketable tool for school promotion in peripheral coastal regions. If this happens, there is a concern that the students and parents, like those in this study, who seek the benefits of the non-competitive, informal style and structure of surfing bukatsu activities may hesitate to join, thereby repeating the issues and concerns associated with traditional bukatsu activities. As Wintle [42] (p. 181) writes, “For some participants, an element of competition can be a motivating factor whilst for others it is not. PE teachers should carefully consider how competition is presented. Competition might not be for everyone or appropriate at all times. Allowing some choice in this area is perhaps key.” There is room for debate on the advantages and disadvantages of focusing on competition or informal surfing, and how to best balance them through bukatsu activities in the future. Perhaps new meanings of “competition” could also be reimagined through the incorporation of lifestyle sports within PE curriculums.

Shifting attention from competition to community, this study shows how the incorporation of lifestyle sports into PE curricula requires community engagement. The new and emerging connections between the surfing bukatsu, the local community, businesses, and the natural environment have demonstrated the necessity of community engagement. The literature in Japan [10] and in the West [42] suggest that establishing greater connections between PE programs and the local community can increase the likelihood of maintaining physical activity habits as an adult. King and Church [13] further maintain that participation in lifestyle sports can enhance the bond between students and place and foster “community building” within PE curriculums. These authors argue that incorporating lifestyle sports like surfing into the public education system may have a greater capacity to connect students with their local environments. Other research has shown that, despite the global growth of lifestyle sports, increasing demand from students, and recognition of the beneficial outcomes, there has been a reluctance to incorporate them into school curriculums [12,14]. This is because integrating lifestyle sports into PE curriculums is relatively uncharted territory that requires further planning, organization, and resources that many schools do not have [15,36]. Concerns around logistical issues, lack of time, funding, safety, and access to resources and facilities are some of the key constraints [14]. This study demonstrates that collaboration with the surrounding community is an important step forward to connecting schools with the local community.

It is argued that traditional sports bukatsu in Japan are often limited to school activities and are not connected to the local community [10]. This was epitomized in the first year when the surfing bukatsu had to practice in the school’s swimming pool. However, due to the nature of surfing, it was found that regular activities must take place in the ocean, a community space. The bukatsu becomes visible to the community, with their presence felt daily. This study demonstrates how this attracted new assemblages of cooperation with local business, religious groups, large airlines, and hotels that all enthusiastically supported their efforts. In addition, as the teachers did not have the qualifications to be surf coaches, an external advisor was necessary for the technical and risk management aspects of surfing instruction. Many of these new relations were more emergent than planned, which indicates that the surfing bukatsu could be considered a “fusion” with community, a term which Otake and Ueda [10] suggests is more intricately embedded than a concept of cooperation. One important aim of lifestyle sports in PE curriculums could be to promote a holistic system that does not begin and end at the boundaries of school facilities, leading the way towards a reorganization of school sporting activities. Understanding the emergent meanings, experiences, and practices as observed through this study of surfing bukatsu offers initial insights into the possibilities and limitations of the transition from “sports clubs” in schools to “community sports”, characterized as a fusion of school and community. By offering detailed insights into the case of Aoshima, it is hoped that these findings may help to inform understandings for other schools and for other sports as lifestyle sports become increasingly incorporated in PE programs across Japan and throughout the globe.

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study offered contextual insights into the shifting meaning, experiences, and practices of social relations, competition, and community engagement as they are currently unfolding in the context of bukatsu reform in rural Japan. Doing so, we showed how the incorporation of lifestyle sports in PE has the potential to encourage a co-constitutive student/school/community revitalization. In emphasizing the cultural specificities of the emergent meanings, experiences, and practices of lifestyle sports within the bukatsu system, the findings of this study are not intended to be generalizable or to evaluate such programs as “good” or “bad”, or “better” or “worse”. Rather, the intention was to offer detailed understandings of how the lifestyle sport of surfing is currently being incorporated into the public education system in Japan to examine the transforming meanings and experiences of both surfing and bukatsu that result. Doing so, we highlight the importance of examining the culturally and site-specific character of how lifestyle sports are assembled in different contexts, especially in lesser-researched non-Western ones. We argue that by paying greater attention to particular histories and socio-cultural relationships informing the incorporation of lifestyle sports into public education systems in specific cultural contexts, the field will be in a better position to understand the different ways that lifestyle sports are being localized into public education systems as they continue on the path of global expansion. Knowing such details will help to ensure that the professionalization, institutionalization, and globalization of lifestyle sports does not turn into the flattening out of sporting and PE social, cultural and site-specific difference and diversity.