Abstract

(1) Background: The current study aimed to examine the mediating role of psychosocial factors in academic performance in higher education based on the adaptation of teaching due to COVID-19. (2) Methods: The methodological design is descriptive–exploratory, cross-sectional, and ex post-facto, using a structural equation model in a sample of 824 university students from Granada. For data collection, the AF-5 questionnaire was used for self-concept; EME-E for motivation, REIS for emotional intelligence, and CD-RISC for resilience, in addition to a specific questionnaire for sociodemographic and academic data. (3) Results: The findings show that (a) academic performance was positively related to personal competence and inversely related to self-confidence, with a higher regression weight in students who did not experience adaptations; that (b) there is a positive relationship between intrinsic motivation and academic performance; that (c) personal competence helped to decrease demotivation in students; and that (d) a positive self-concept acts as a protective factor against demotivation. (4) Conclusions: Therefore, the relevance of educational institutions in the holistic development of young adults is highlighted, ensuring not only academic success but also the emotional and personal well-being of students in a constantly changing world.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in late 2019, has transformed numerous aspects of our daily life, prompting various changes in the global education system [1]. The rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, responsible for the disease, triggered massive closures of educational institutions in almost every country, affecting both basic and higher education systems (UNESCO, 2020). Indeed, at the height of the pandemic, it was estimated that over 90% of students worldwide were out of classrooms, an unprecedented event in modern history [2].

This unexpected situation spurred educational authorities and educators to seek swift alternatives to continue the teaching–learning process. The rise of online education, previously a supplementary or alternative modality, became the primary tool with which to maintain educational continuity [3]. Despite the positive adaptability shown by many educational systems, significant challenges in the development of higher education students were unveiled.

Confinement measures and social distancing, although essential from a public health perspective, have had significant impacts on students’ mental health and emotional well-being [4]. Emerging adulthood, a critical phase of human development spanning approximately 18 to 25 years, has historically been associated with identity exploration, independence, and the establishment of personal and professional goals [5,6]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced unique and unprecedented challenges for this demographic cohort. The repercussions of the health crisis on emerging adulthood have manifested in various interrelated domains, ranging from educational and work contexts to psychosocial and mental health [7].

From an educational perspective, many young adults in university training processes had to abruptly adapt to distance learning modalities, with the ensuing technological, pedagogical, and motivational challenges this entails [8]. Moreover, the economic repercussions of the pandemic led to increased unemployment and job insecurity, particularly disturbing for those young individuals transitioning into the job market or experiencing their first work encounters [9].

Psychosocially, distancing and confinement measures have curtailed opportunities for social interaction, affecting the building and consolidation of interpersonal relationships, crucial at this stage [10]. This limitation, coupled with economic and academic uncertainty, has amplified negative emotional states such as anxiety, stress, and depression among young adults [11].

Isolation has also exacerbated pre-existing challenges in emerging adulthood, such as identity search and a sense of belonging. For many, the absence of traditional rites of passage, such as graduations or entering a first job, has left a void in the process of crafting their personal narrative [12,13]. The long-term implications of these symbolic losses remain to be determined.

However, it is crucial to point out that, while challenges have been significant, there have also been cases of resilience and adaptability among young adults. Many have found innovative ways to maintain social connections, discovered new passions, or took the situation as an opportunity to re-evaluate life goals and aspirations [14,15].

Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic has deeply influenced emerging adulthood, affecting multiple dimensions of young adults’ lives. While the long-term nature of these repercussions is still under research, it is undeniable that this generation of young adults faces a unique landscape, shaped by unparalleled challenges and opportunities.

Furthermore, the abrupt transition to virtual modalities in educational contexts can lead to significant repercussions for academic performance and certain psychosocial aspects of university students. From a pedagogical standpoint, online interaction lacks certain tactile and in-person elements intrinsic to traditional learning, potentially affecting content comprehension and retention, leading to low levels in academic performance. Moreover, facing technical or connectivity adversities can spawn frustrations and trigger inefficient coping responses, especially in students who do not possess pre-established resilient strategies. Such circumstances can lead to episodes of demotivation or apathy towards the educational process.

Concurrently, emotional intelligence, which is paramount for the recognition and management of one’s own and others’ emotions, might be compromised due to the reduction of face-to-face interactions, limiting the development of socio-emotional skills. Therefore, adapting to virtual education demands not only methodological adjustments but also an integrative approach that addresses the emotional and psychosocial needs of students.

In this regard, this study aims to achieve a holistic understanding based on empirical data regarding how various pertinent variables operate on academic performance for university students, such as adversity control, emotions, and factors linked to psychosocial aspects. Additionally, the study seeks to ascertain how these elements function in two distinct modalities that reflect the pandemic and the post-pandemic periods. It is also worth noting that, while there is current scientific research that includes post-COVID studies, a holistic comprehension of these interconnected variables has not yet been undertaken.

Research Problem and Hypotheses

The purpose of this study was to investigate the mediating role between psychosocial factors and academic performance based on the effect of COVID-19 on the educational process of university students. In line with this central objective, the following research question (RQ) and hypotheses (Hx) were structured for the study:

RQ: How have psychosocial variables, such as emotional intelligence, motivation, self-concept, and resilience, been influenced by the adaptations to changes in educational systems and the academic performance of emerging adults due to COVID-19?

H1.

The emotional intelligence of emerging adults will play a vital role in adapting to changes in educational systems following COVID-19.

H2.

The motivation levels in emerging adults will be negatively influenced by the circumstances of COVID-19 and will be directly related to academic performance during the pandemic.

H3.

Those emerging adults with a positive self-concept will show greater resilience and adaptability to pandemic-induced educational changes.

H4.

Resilience, enhanced by psychosocial factors during COVID-19, will predict positive levels in academic performance.

H5.

Emerging adults with high levels of emotional intelligence and motivation will better adapt to educational changes and achieve higher academic performance during COVID-19 compared with those with lower levels in these variables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

The present study adopts a non-experimental, quantitative approach with a descriptive and exploratory design. It is a cross-sectional and ex post facto study conducted through a single measurement in a specific group. The target population of this research consists of university students enrolled at the University of Granada during the 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 academic years. The total number of students enrolled in 2021/2022 for the undergraduate degree was 39,078 and for the master’s degree was 6325, while in the year 2022/2023, the enrollment rate for the undergraduate degree was a total of 43,478 and for the master’s degree was 6409. Following the parameters proposed by Gallego [16], this study included those emerging adults who were willing to participate and who met the condition of being enrolled in a higher education undergraduate or postgraduate program during 2021 and 2022. On the other hand, individuals were excluded if they: (a) had any condition or problem that hindered the proper completion of the questionnaire, and (b) provided incomplete validated scales or responses that generated ambiguity. The sample was initially made up of 1105 participants. However, after applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria, the final sample was 824 emerging adults. Based on the 1105 respondents, a margin of error of 2.93% with a 95% confidence interval was obtained. Likewise, considering the 824 respondents who exceeded the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a margin of error of 3.40% was obtained with a confidence interval of 95%.

2.2. Instruments

In the present study, the following instruments are employed:

- Educational Motivation Scale (EME), which was designed by Núñez et al. [17]. This instrument is structured by 19 items (e.g., “12. Before I had good reasons for going to school, but now I wonder if it is worth continuing”, which are dispersed in four subscales: intrinsic motivation (items 2, 3, 7, 11, 15, 16), internal extrinsic motivation (items 5, 6, 9, 13, 18, 19), external extrinsic motivation (items 1, 10, 14), and demotivation (items 4, 8, 12, 17). The responses are scored based on a seven-point Likert-type scale, from: 1 “Does not correspond at all” to 7 “Completely corresponds”. This scale obtained an alpha value of α = 0.886 and an omega value of ω = 0.888. Likewise, when highlighting the estimated values of alpha and omega in the different dimensions of motivation, it is observed that intrinsic motivation obtained α = 0.881 and ω = 0.88, internal extrinsic motivation denoted α = 0.865 and ω = 0.864, external extrinsic motivation showed α = 0.441 and demotivation indicated α = 0.855 and ω = 0.850. Therefore, good values (+0.8) are observed in all dimensions except for external extrinsic motivation.

- Self-Concept Form-5 Questionnaire (SF-5). This instrument was developed by García and Musitu [18] and is based on the theoretical model of Marsh [19]. It is made up of 30 items (e.g., “1. I do academic work well”) that are scored using a Likert-type scale of 5 options, where 1 is “Never” and 5 is “Always”. Self-concept is grouped into five dimensions according to this instrument, which are defined by academic self-concept (items 1, 6, 11, 16, 21 and 26), social self-concept (items 2, 7, 12, 17, 22 and 27), emotional self-concept (items 3, 8, 13, 18, 23 and 28), family self-concept (items 4, 9, 14, 19, 24 and 29) and physical self-concept (items 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30). This scale obtained an alpha value of α = 0.872 and an omega value of ω = 0.871. Likewise, when highlighting the estimated values of alpha and omega in the different dimensions of self-concept, it is observed that the physical self-concept obtained an α = 0.777 and ω = 0.777, the social self-concept denoted an α = 0.816 and ω = 0.832, the family self-concept showed an α = 0.861 and ω = 0.861, the academic self-concept indicated an α = 0.812 and ω = 0.816 and the emotional self-concept determined an α = 0.833 and ω = 0.835. Therefore, good values are observed (+0.8) in the dimensions of social, family, academic and emotional self-concept; however, the physical self-concept points to an acceptable value (+0.7).

- The REIS scale is an instrument designed to measure emotional intelligence (EI) and designed by Pekaar et al. [20]. This scale is composed of 28 items, which are focused on four factors, the evaluation of emotions focused on oneself (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7), evaluation of emotions focused on others (items 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14), personal emotional regulation (items 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21), and other-focused emotional regulation (items 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28). The score is based on a Likert scale where 1 means “Totally disagree” and 5 means “Totally agree”. This scale obtained an alpha value of α = 0.907 and an omega value of ω = 0.902. Likewise, when highlighting the estimated values of alpha and omega in the different dimensions of emotional intelligence, it is observed that the evaluation of emotions focused on oneself obtained an α = 0.904 and ω = 0.905, the evaluation of emotions focused on others denoted a α = 0.860 and ω = 0.868, self-focused emotion regulation showed α = 0.822 and ω = 0.825, and other-focused emotion regulation indicated α = 0.856 and ω = 0.860. Therefore, good values (+0.8) are observed in all dimensions of emotional intelligence.

- The CD-RISC scale, conceived by Connor and Davidson [21], aims to assess resilience. It is composed of 25 items, for example, “1. I am able to adapt to change”, and these are arranged in a range of five points, as follows: 0, not true at all; 1, rarely true; 2, sometimes true; 3, often true; and 4, true almost all of the time. The instrument is made up of five dimensions, which are evaluated through different items: persistence–tenacity (items: 10, 11,12, 16, 17, 23, 24, 25); control under pressure (6, 7, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20); adaptability (1, 2, 4, 5, 8); control and purpose (13, 21, 22); and spirituality (3, 9). The scores for each item are added and interpreted so that the higher the score, the more resilient the individual is. This scale obtained an alpha value of α = 0.890 and an omega value of ω = 0.891. Likewise, when highlighting the estimated values of alpha and omega in the different dimensions of resilience, it is observed that personal competence and tenacity obtained an α = 0.799 and ω = 0.800, trust and tolerance to negative effects denoted an α = 0.699 and ω = 0.702, positive acceptance of change showed α = 0.658 and ω = 0.664, control capacity indicated α = 0.575 and ω = 0.584 and spiritual influence denoted α = 0.615. Therefore, acceptable values (+0.7) are observed in all dimensions of resilience.

2.3. Procedure

Initially, the process was spearheaded by the Department of Research Methods and Diagnosis in Education in collaboration with the Department of Musical, Plastic, and Corporeal Expression at the University of Granada. A questionnaire was designed using Google Forms, incorporating the four previously mentioned instruments. Additionally, the questionnaire detailed the purpose and nature of the study, the research tools utilized, and the information management, which would strictly serve scientific and anonymous purposes. It is pertinent to note that this investigation adhered to the guidelines set out by the Helsinki Declaration (2008 version) and ensured confidentiality in line with Law 15/1999 from December 13. The entire process was overseen by the University of Granada through its Research Ethics Committee, under reference 2668/CEIH/2022.

Following the questionnaire’s finalization, online data collection ensued, and the subsequent data processing began. Initially, incomplete questionnaires or those with ambiguous questions were discarded to ensure reliability. After this review, the database was refined, and the information was imported into the IBM SPSS® 23.0 software for structuring. Throughout this procedure, the lead researcher took personal charge to guarantee accurate statistical analysis and prevent potential errors.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS® 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and IBM AMOS® 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) software. Basic descriptive analyses were carried out through frequencies and means. Moreover, the normal distribution of data was verified using skewness and kurtosis values (values less than 2 indicate a low level of dispersion). On the other hand, the internal consistency of the scales was evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients and McDonald’s Omega, setting the reliability index at 95%. Lastly, to verify the model’s fit level, the chi-squared test, the comparative fit index (CFI), the normed fit index (NFI), and the incremental fit index (IFI) were employed, which should exhibit values above 0.95 for a suitable fit. Likewise, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was used, which should display values less than 0.05.

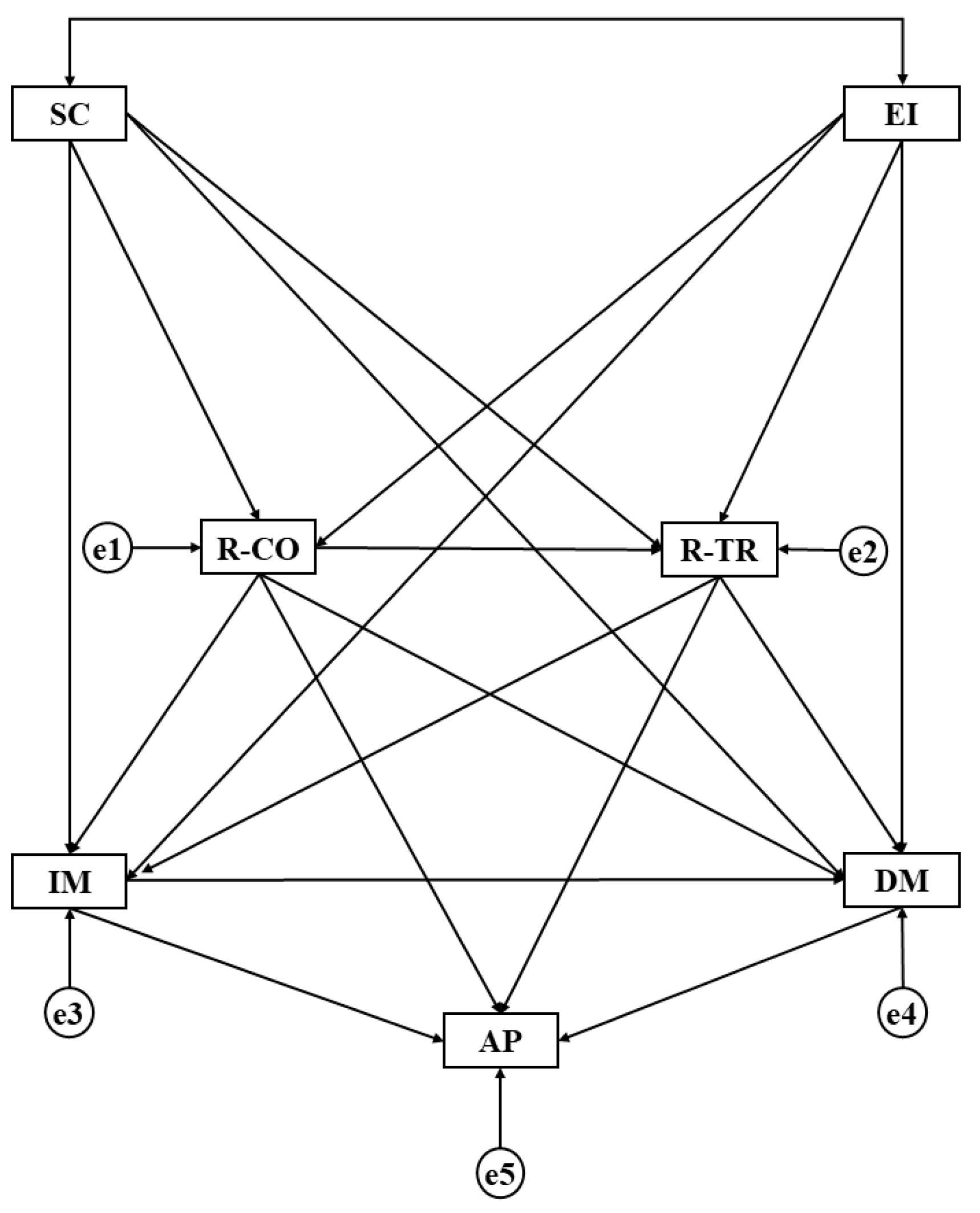

Figure 1 presents the developed theoretical model, unveiling the structural relationships between self-concept, emotional intelligence, resilience, motivation type, and academic performance. Moreover, a multi-group analysis was employed to understand the differences among students who underwent instructional mode adaptations in the pandemic’s last year. Specifically, the structural model comprises seven observable variables: SC, self-concept; EI, emotional intelligence; R-CO, resilience-competence; R-TR, resilience-trust; IM, intrinsic motivation; DM, demotivation; and AP, academic performance. These variables are represented by squares and use an error term (circle) when influenced by another variable. Thus, any structural effect is depicted with a straight arrow, originating from the predictor variable and ending at the dependent variable. Conversely, bidirectional relationships (correlations and covariances) are shown as vectors with an arrow on each end and do not utilize error terms.

Figure 1.

Theorical structural model. Note: SC, self-concept; EI, emotional intelligence; R-CO, resilience-competence; R-TR, resilience-trust; IM, intrinsic motivation; DM, demotivation; AP, academic performance.

3. Results

Firstly, and due to the way in which the instruments used to obtain the variables are employed here in a cross-sectional study, it is essential to perform multicollinearity tests of the scales to ensure the robustness and precision of the findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Multicollinearity tests of the scales to ensure the robustness and precision of the findings.

In this case, the EME scale shows a Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin measure of sampling adequacy of 0.914, which is excellent. Likewise, Bartlett’s sphericity test supposes the rejection of the null hypothesis H0, denoting a correlation between the variables (χ2 = 8667.92; df = 171; p = 0.000). Similarly, for the factor analysis that was carried out, an explained variance of 67.02% was obtained for its structure in four factors, being adequate values. On the other hand, the SF-5 self-concept scale presents a Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin measure of sampling adequacy of 0.863, which is acceptable. Likewise, Bartlett’s sphericity test supposes the rejection of the null hypothesis H0, denoting a correlation between the variables (χ2 = 10535.50; df = 435; p = 0.000). Similarly, for the factor analysis carried out, an explained variance of 56.29% was obtained for its structure in five factors, being adequate values.

The third scale evaluated was the REIS emotional intelligence questionnaire. This presents a Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin measure of sampling adequacy of 0.919, being excellent. Likewise, Bartlett’s sphericity test supposes the rejection of the null hypothesis H0, denoting a correlation between the variables (χ2 = 11396.75; df = 378; p = 0.000). Similarly, for the factor analysis carried out, an explained variance of 57.44% was obtained for its structure in five factors, being adequate values. Finally, the CD-RISC scale to evaluate resilience presents a Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin measure of sampling adequacy of 0.921, which is excellent. Likewise, Bartlett’s sphericity test supposes the rejection of the null hypothesis H0, denoting a correlation between the variables (χ2 = 6227.99; df = 300; p = 0.000). Similarly, for the factor analysis carried out, an explained variance of 51.65% was obtained for its structure in five factors, being an acceptable value although slightly lower than the previous ones.

Secondly, the fit indices of the scales used for the sample under study are reported (Table 2). The root mean square error (RMR) index will imply a good fit with values close to 0, as shown in the SF-5, REIS and CD-RISC scales, obtaining a not-so-appropriate value for the EME scale. In the case of the goodness of fit index (GFI), a value greater than 0.9 was obtained in all cases, reflecting acceptable values. On the other hand, the normalized fit index (NFI), the incremental fit index (IFI) and the confirmatory fit index (CFI) will show acceptable levels of fit with values close to 0.9, as happens for all scales. However, it should be noted that the NFI value, which was obtained in the empirical data of the sample, was not ideal for the SF-5, REIS and CD-RISC scales, although it was relatively close to the threshold value. Finally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) reflected appropriate values, being less than 0.08 for the selected sample size.

Table 2.

Fit indices of the scales used for the sample under study.

Thirdly, and as a prior step to carrying out the structural equation model, a bivariate correlation matrix of the variables to be included in the model is created (Table 3). Specifically, statistically significant correlations are observed for most variables, except for the relationship between academic performance and emotional intelligence and self-confidence, in addition to the relationship between self-confidence and demotivation. Based on these findings, the interest of executing the structural equation model with multigroup analysis becomes evident.

Table 3.

Matrix of bivariate correlations of the variables to be included in the structural model.

The statistics used to determine the model fit displayed excellent results in all instances. Firstly, the chi-square test yielded a non-significant value, confirming the acceptance of the null hypothesis and the designed structural model (χ2 = 0.350; df = 4; p = 0.986). Additionally, authors such as Byrne [22] recommend providing other reference indices, from which we also obtained excellent values that allow for the acceptance of the structural equation model: NFI = 0.999; RFI = 0.997; IFI = 0.997; CFI = 0.999; RMSEA = 0.000; RMR = 0.033; SRMR = 0.002; GFI = 1.000; and AGFI = 0.998.

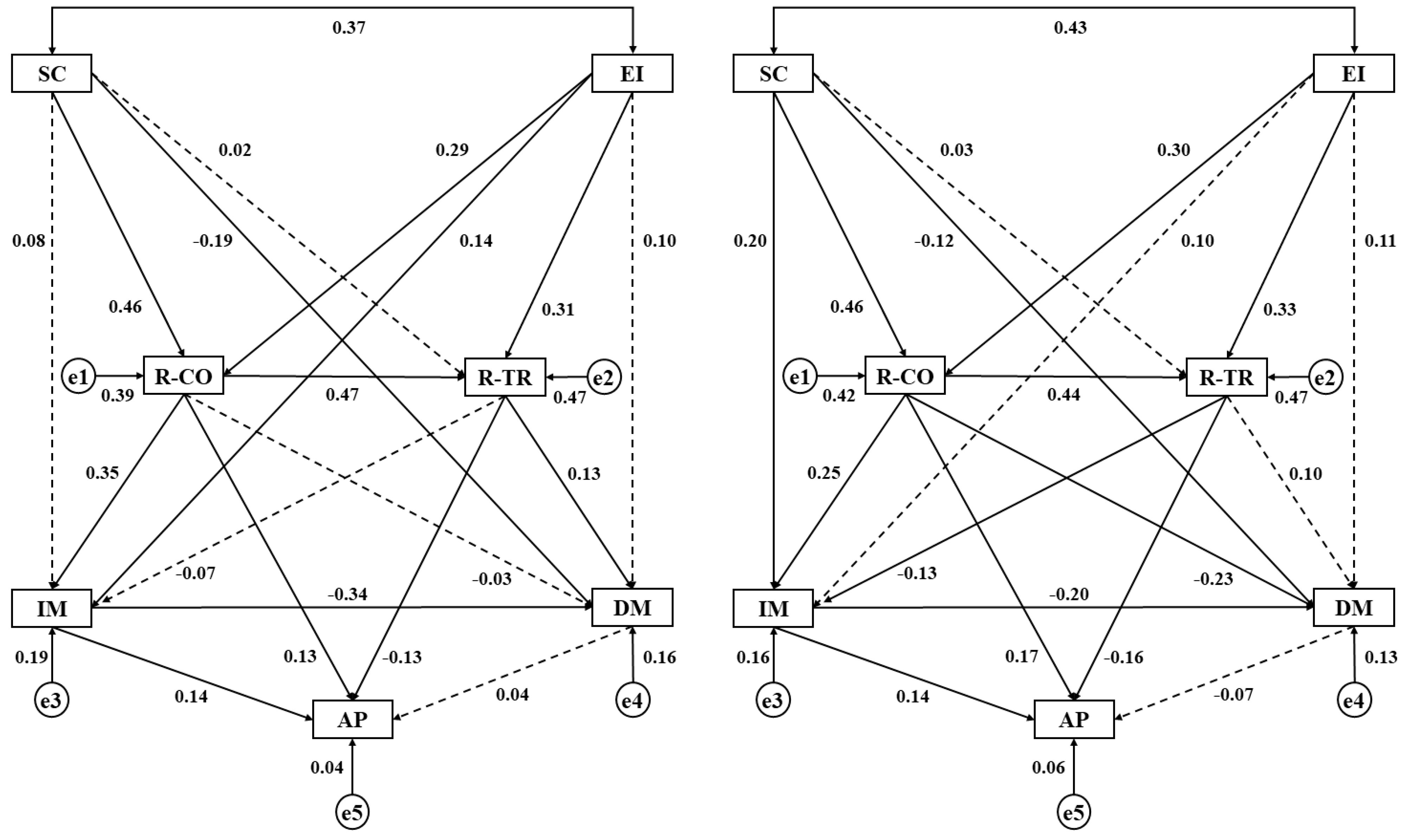

Primarily, Table 4 and Table 5 illustrate the regression weights for university students who underwent adaptation to virtual learning in their past course, with the standardized regression weights depicted in Figure 2. If we approach the structural model from the top down, a positive association between self-concept and emotional intelligence is observed first, resulting in a higher regression weight for students who did not experience teaching adaptation (β = 0.433 vs. β = 0.367). Similarly, in this section, the structural relationship between these dimensions and two basic elements of resilience is noted. In both student groups, emotional intelligence was positively associated with personal competence (β = 0.290 vs. β = 0.297) and self-confidence (β = 0.311 vs. β = 0.331) with nearly analogous regression weights. For self-concept, a significant and positive relationship was found only with personal competence (β = 0.461 vs. β = 0.459). Finally, it is crucial to note that there was a direct structural effect between the two studied resilience dimensions, being higher in students who experienced teaching adaptations (β = 0.471 vs. β = 0.440).

Table 4.

Regression weights and standardized regression weights for students who underwent adaptation in the received teaching.

Table 5.

Regression weights and standardized regression weights for students who continued with their mode of instruction.

Figure 2.

Structural equation models. Note: SC, self-concept; EI, emotional Intelligence; R-CO, resilience-competence; R-TR, resilience-trust; IM, intrinsic motivation; DM, demotivation; AP, academic performance. Left (students who underwent teaching adaptation); Right (students who did not undergo teaching adaptation). Arrows show statistically significant differences. Arrows with dotted lines show the absence of statistically significant differences.

From the model’s mid-section, the relationships between the two types of motivation and the three studied psychosocial factors become evident. For students who experienced teaching adaptation, a direct relationship between emotional intelligence and intrinsic motivation (β = 0.137) was observed, which was not significant for the other group. On the contrary, the opposite trend was seen in the self-concept of students who had not undergone changes, with a positive and significant relationship evident only in them (β = 0.204). Likewise, concerning demotivation, in both groups, no significance was observed for its relationship with emotional intelligence, revealing a significant and inverse association with self-concept in both groups (β = −0.187 vs. β = −0.125).

Similarly, the relationships between motivation types and resilience dimensions, with notable differences in the two studied groups, are observable. Significance was observed between intrinsic motivation and personal competence, presenting a positive relationship in both groups (β = 0.347 vs. β = 0.253) and being stronger in students who underwent adaptations. Conversely, the relationship between intrinsic goals and self-confidence was only significant in students without adaptations, also showing a negative regression weight (β = −0.130). Emotional competence was not associated with demotivation in students with adaptations, revealing a significant and negative relationship in students who continued their teaching as usual (β = −0.228). Likewise, a direct relationship existed between demotivation and self-confidence for students with adaptations (β = 0.132), with no significance found in the other group.

Finally, the model’s lower section displays the structural effect of academic performance with the types of motivation and resilience. Firstly, it is essential to note that the relationship between intrinsic motivation and demotivation was significant, inverse, NS stronger in students who experienced teaching adaptations (β = −0.340 vs. β = −0.200). Likewise, there was no structural effect between academic performance and demotivation in both student groups, revealing a positive relationship with intrinsic motivation in both (β = 0.141 vs. β = 0.138). In conclusion, academic performance was positively related to personal competence (β = 0.135 vs. β = 0.170) and inversely related to self-confidence (β = −0.134 vs. β = −0.158), resulting in a higher regression weight in students who did not experience adaptations.

Table 6 shows the standardized direct and indirect effects for the variables of the structural model in order to facilitate the understanding of the findings previously obtained. Specifically, the upper part of the table shows the values for those students who experienced adaptations in their teaching modality. On the other hand, the lower part of the table shows the values for students who did not suffer adaptation in their teaching modality.

Table 6.

Standardized direct and indirect effects for the variables of the structural model according to the grouping variable.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to describe the mediating role of psychosocial factors in academic performance in higher education during the progression of a teaching system that had been adapted due to COVID-19. The study involved a sample of 824 emerging adults from public universities in Andalusia. In this context, similar studies were conducted by Gómez et al. [23], Narváez and Obando [24], Palacios and Coveñas [25], Quezada et al. [26], and Al-Kumaim et al. [27].

Multiple findings emerged, suggesting strong and positive relations between psychosocial variables as mediators in academic performance. Considering the main discoveries, a positive relationship was found between self-concept and emotional intelligence. This relationship was stronger among students who did not experience adaptations in their teaching modality. Several studies have explored this relationship, identifying clear patterns suggesting a positive correlation between the two constructs. Quezada et al. [26] found that individuals with a stronger, positive self-concept displayed better emotion recognition and regulation skills. These findings align with theories suggesting that a robust self-concept provides a solid framework from which individuals can interpret and manage emotions more effectively [25]. On the other hand, emotional intelligence, emphasizing understanding and regulating emotions, might enhance and nourish a positive self-concept, creating a mutual reinforcement cycle.

Similarly, self-concept was only positively related to personal competence and not to confidence, consistent across both groups. The link between self-concept and personal competence has been the subject of various developmental psychology studies. Research has proposed that a positive self-concept might be a predictor of high levels of personal competence [28]. This correlation suggests that individuals with a positive self-image are more inclined to feel capable and efficient in task execution and challenge confrontations [29].

Within the framework of emerging adulthood, this link becomes especially relevant. Emerging adults with a solid self-concept tend to show greater resilience against adversities while also displaying a greater disposition to assume roles and responsibilities demanding a high degree of personal competence [30,31].

Furthermore, the relationship between the studied resilience dimensions was found to be stronger among students who experienced teaching adaptations, being positive in both cases. Although resilience is often viewed as a unidimensional construct, recent research has emphasized its multifaceted nature, arguing it can be broken down into various dimensions, like adaptability, perseverance, and emotional balance [32]. Savitsky et al. [33] note that adaptability might be related to a student’s ability to transition and effectively utilize online learning platforms, while emotional balance could reflect the ability to manage stress and anxiety associated with the uncertainty of the pandemic.

A key finding was that EI predicted greater intrinsic motivation among students who experienced adaptations, while self-concept was the predictor of higher intrinsic motivation among students without adaptations. Based on parameters set by Fernández-Lasarte et al. [34], EI emerges as a core concept. In turn, intrinsic motivation is vital for profound and sustained learning. However, with the abrupt change in educational dynamics due to COVID-19, many students found it challenging to maintain optimal interest and engagement levels. Here is where emotional intelligence might play a predictive role.

Students with high EI possess the skills to regulate their emotions, empathize with others, and adapt to changing situations. According to Jiménez [35], these skills are especially relevant in crisis times. Indeed, for Jiménez [35], these abilities can act as buffers against the frustration, uncertainty, and isolation many felt during the transition to remote learning. Moreover, they can help students reconnect with the passion and interest for learning, crucial factors for intrinsic motivation [36].

However, in the educational context, as per Guerrero et al. [37], self-concept intertwines directly with student motivation and academic performance. Students with a positive self-concept tend to have a firm belief in their abilities. This confidence, derived from past experiences and bolstered by self-evaluation, can act as a catalyst for intrinsic motivation. Believing in their abilities, these students are more inclined to tackle academic challenges not because they are compelled, but because they see these challenges as opportunities to grow and learn [38].

It is worth noting, as per Guerrero [37], that the predictive nature of self-concept regarding intrinsic motivation does not suggest a one-way relationship. It is a dynamic and bidirectional process: while a positive self-concept can foster higher intrinsic motivation, the act of being intrinsically motivated and experiencing academic success can, in turn, reinforce a positive self-concept.

Similarly, personal competence was found to predict greater intrinsic motivation among students who experienced adaptations. According to Quiroga and Peláez [39], students who perceive that they possess the skills and capabilities necessary to face and overcome challenges are likely more motivated to engage with their studies, even when circumstances are adverse. This contributes to a greater implication in academic work.

Indeed, given the plethora of challenges students have faced due to COVID-19 adaptations, the belief in one’s competence becomes an invaluable resource. By believing in their capabilities, students not only face academic tasks with greater bravery but also experience a sense of achievement and satisfaction that further reinforces their intrinsic motivation [40].

In turn, among students without adaptations, confidence was found to negatively associate with intrinsic goals. This could be argued based on studies by Stover et al. [41], suggesting that students with unwavering confidence, in a constant academic context, might become complacent. Being certain of their abilities, without the challenge of adapting to a new learning modality, they might feel less of a need to push themselves towards more challenging intrinsic goals. The absence of novelty and challenge could, paradoxically, lead these students to rely on their confidence to merely “get by” in the educational process, rather than deeply immerse themselves in a love for learning.

On the other hand, positive self-concept acted protectively against demotivation in both groups, especially when there were adaptations. Self-concept, as per Salomón et al. [42], especially if positive, can act as a shield, protecting individuals from one of the most detrimental obstacles in any learning or growth trajectory: demotivation.

Therefore, a positive self-concept does not necessarily imply an inflated view of oneself but rather a balanced and realistic appreciation of one’s capabilities and worth. This perception becomes the internal compass guiding individuals through the often-tumultuous seas of life. Against the backdrop of education and learning, where challenges are constant and adaptability is vital, demotivation can arise as a dark cloud. This lack of interest or enthusiasm can result from multiple factors: repeated failures, lack of adequate feedback, feelings of incompetence, among others. However, a positive self-concept, once internalized, can act as a protective umbrella against this rain of demotivation [6,34,43].

Moreover, personal competence was found to help decrease demotivation among students in whom no adaptations occurred. On the other hand, personal competence helped reduce demotivation in students where there were no adaptations. On the winding path of academic development, students encounter challenges that test not only their intellect but also their character. Amid these trials, a factor emerges that stands out for its ability to act as an anchor in stormy times: personal competence. This quality, according to Flórez et al. [32] refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to face and overcome challenges and has profound effects on the educational experience, especially concerning demotivation. This demotivation can result from negative academic experiences, a lack of clarity in objectives, or a feeling of incompetence in tasks. Without appropriate interventions, this state can persist, leading the student into a cycle of poor performance and an apathetic attitude towards learning. In this scenario, personal competence emerges as a vital counterweight.

For Salomón et al. [42], a student who feels they possess the skills and resources necessary to face challenges is more likely to approach academic tasks with a proactive attitude. They not only see challenges as growth opportunities but are also more willing to persevere through difficulties because they trust their ability to overcome them. Similarly, according to Jiménez et al. [44], personal competence operates as a recovery system. Even in moments of doubt or disinterest, a student with a strong sense of competence can recall times when they overcame similar challenges, using those memories as a boost to reignite their motivation and to increase their academic performance.

Similarly, there was a positive relationship between intrinsic motivation and academic performance in both groups. The educational realm has witnessed numerous studies aiming to decipher the factors determining academic success. One variable that has sparked increasing interest is intrinsic motivation, that inner force driving students to learn for the sheer love of learning, independent of external rewards or incentives. According to Deci and Ryan [45], this type of motivation, which originates within the individual, has positioned itself as a crucial element that, according to Zwane and Mukuna [46], Frazier et al. [47], shares a positive relationship with academic performance. At the heart of intrinsic motivation, as per Doménech-Betoret et al. [48], lies the genuine desire to acquire new knowledge or skills. It is the student who reads an extra book because they are fascinated by the topic or the one conducting experiments at home purely out of curiosity. This passion for learning translates into greater dedication, attention, and effort—factors naturally leading to improved academic performance [49,50,51].

Interestingly, intrinsic motivation affects the learning process. An intrinsically motivated student does not merely memorize information; they seek to understand, relate, and apply it. This depth in the learning process, driven by a genuine desire to comprehend, ensures more effective retention and understanding of the material [45,46].

It is crucial to note that the relationship between intrinsic motivation and academic performance is not one-way. As the student experiences academic achievements driven by their intrinsic motivation, these very achievements reinforce and fuel that motivation, creating a virtuous cycle of learning and success.

On the other hand, academic performance was positively related to personal competence and inversely related to self-confidence, with a higher regression weight among students who did not experience adaptations. According to Quiroga and Peláez [39], personal competence and self-confidence emerge as two key dimensions, albeit with distinct and sometimes surprising influences. Personal competence is an individual’s perception of their ability to perform tasks and confront challenges and has been shown to have a positive relationship with academic performance. This implies that students who see themselves as capable and prepared to tackle academic challenges tend to yield better results. This perception reinforces their resilience, determination, and perseverance in the face of obstacles in the educational process [39,52,53].

On the other hand, self-confidence, understood by Noriega et al. [40] as a generalized belief in one’s abilities, presents a more complex relationship. While confidence is vital for well-being and self-efficacy, an excess of it, without actual grounding in skills or knowledge, can harm academic performance. Students who place undue confidence in their abilities, without this confidence being reflected in their real competencies, might avoid confronting their areas of weakness, leading to subpar academic results [54].

In addition, and according to Kivlighan et al. [50] and Martinez et al. [51] this interaction between personal competence and confidence reveals the delicate balance on which academic success sits. While the former acts as a driving force, the latter, when not well-calibrated, can divert students off the path to excellence. It is essential, then, for educators and tutors to recognize and understand these dynamics in order to guide the academic and personal development of their students effectively.

Taking into special consideration all the findings mentioned above, it is essential to highlight the following conclusions for the structural equation model:

- The relationship between self-concept and emotional intelligence is positive. Furthermore, it is stronger among students who did not experience adaptations in their teaching modality. Therefore, this indicates that a solid self-concept can provide a strong framework from which individuals can interpret and manage emotions more effectively.

- The self-concept was only positively related to personal competence and not to confidence, which was consistent in both groups. Additionally, there was a relationship between the resilience dimensions, which was stronger among students who experienced adaptations, but positive in both cases. This suggests that individuals with a positive self-image are more inclined to feel capable and efficient in task execution and challenge confrontations.

- EI predicted greater intrinsic motivation among students who experienced adaptations. On the other hand, self-concept predicted higher intrinsic motivation among students without adaptations. Additionally, personal competence predicted higher intrinsic motivation among students who experienced adaptations.

- Confidence was negatively associated with intrinsic goals among students without adaptations. However, a positive self-concept acted protectively against demotivation in both groups, especially when there were adaptations.

- Lastly, there was a positive relationship between intrinsic motivation and academic performance in both groups. Moreover, academic performance was positively related to personal competence and inversely related to self-confidence, with a higher regression weight among students who did not experience adaptations.

These findings indicate that, in the context of higher education, the influence of psychosocial factors on academic performance has been the subject of extensive study in recent years. These factors, encompassing variables such as motivation, self-concept, EI, and resilience, play a crucial role in how students face their academic and professional challenges. It is evident that mere access to information and teaching resources does not guarantee academic success; it is the psychosocial fabric that impacts knowledge assimilation and educational achievements. It is imperative, therefore, for higher education institutions to recognize and prioritize these factors, designing interventions and support programs that address not only the curricular component but also the student’s psychosocial well-being. By fostering an academic environment that is aware and promotes psychosocial balance, the likelihood of student success is maximized, enriching the educational and formative quality of the institution.

Lastly, it is essential to highlight the primary limitations of this study. Specifically, it is crucial to mention the methodological design, being descriptive, cross-sectional, ex-post-facto, and measuring in a single group. An inherent limitation of this design type is its descriptive and cross-sectional nature, which does not allow for the establishment of causality relations or for the determination of cause and effect. The ex-post-facto approach introduces its own limitations, including the lack of control over the analyzed variables, a common characteristic in studies of this nature. Finally, it is pertinent to mention that, by not incorporating certain variables into the study, there is a risk of overlooking demographic, academic, social, or psychological aspects that might be crucial to adequately address the researched question.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.G.-V., M.C.-S. and R.C.-C.; methodology, M.A.G.-V.; software, R.C.-C.; validation, M.A.G.-V., M.C.-S. and R.C.-C.; formal analysis, M.A.G.-V. and R.C.-C.; investigation, M.A.G.-V. and M.P.-M.; resources, M.C.-S. and R.C.-C.; data curation, M.A.G.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.G.-V. and M.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.C.-C.; visualization, M.A.G.-V. and R.C.-C.; supervision, R.C.-C. and M.C.-S.; project administration, M.A.G.-V. and M.P.-M.; funding acquisition, R.C.-C. and M.C.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Granada (protocol code 2668/CEIH/2022 on 2 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this article is not available as it may present identification data of the study subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H. Impact of COVID-19 on education systems and future perspectives. High. Educ. Res. 2020, 5, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Viner, R.M.; Russell, S.J.; Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Ward, J.; Stansfield, C.; Mytton, O.; Bonell, C.; Booy, R. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toquero, C.M. Challenges and opportunities for higher education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The Philippine context. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 5, em0063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Olmedo-Moreno, E.M.; Lara-Sánchez, A.J.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Castro-Sánchez, M. Basic psychological needs, emotional regulation and academic stress in university students: A structural model according to branch of knowledge. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, G.; Van’t Land, H.; Jensen, T. The impact of COVID-19 on higher education around the world. IAU Glob. Surv. Rep. 2020, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.N.; Blanchflower, D.G. US and UK labour markets before and during the COVID-19 crash. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2020, 252, R52–R69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psych. 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. Eur. J. Develop. Psychol. 2016, 13, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito-López, J.; Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Zahra-Rakdani, F.; Serrano-García, J. Attitudes and components of mentoring and tutoring and their influence on improving academicperformance. RELIEVE—Rev. Elec. Inv. Eval. Educ. 2023, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanabrias-Moreno, D.; Sánchez-Zafra, M.; Lara-Sánchez, A.J.; Zagalaz-Sánchez, M.L.; Cachón-Zagalaz, J. Factores psicosociales y actividad física en la formación universitaria del futuro profesorado. J. Sport Health Res. 2023, 15, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, C. Diseños ex post facto. Rev. Inv. Psicol. 2020, 15, 256–300. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, J.L.; Martín-Albo, J.; Navarro, J.G.; Suárez, Z. Adaptación y validación de la versión española de la Escala de Motivación Educativa en estudiantes de educación secundaria postobligatoria. Est. Psicol. 2010, 31, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.; Musitu, G. Autoconcepto Forma 5; Tea: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W. The structure of academic self-concept: The Marsh/Shavelson model. J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekaar, K.A.; Bakker, A.B.; van der Linden, D.; Born, M.P. Self-and other-focused emotional intelligence: Development and validation of the Rotterdam Emotional Intelligence Scale (REIS). Personal. Ind. Diff. 2018, 120, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depres. Anx. 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, M.; Gómez, P.; Valenzuela, B. Adolescencia y edad adulta emergente frente al COVID-19 en España y República Dominicana. Rev. Psicol. Clin. Niños Adolesc. 2020, 7, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez, J.; Obando, L. Relación entre factores predisponentes a la deprivación sociocultural y el apoyo social en adolescentes. Rev. Vir. Univ. Catól. Norte 2021, 63, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Garay, J.; Coveñas-Lalupú, J. Predominancia del autoconcepto en estudiantes con conductas antisociales del Callao. Propósitos Represent. 2019, 7, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada, C.; Navarrete, Z.; Sánchez, Y. El autoconcepto e inteligencia emocional como predictores del apoyo social percibido en adolescentes. Rev. Fuentes 2023, 44, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Alhazmi, A.K.; Mohammed, F.; Gazem, N.A.; Shabbir, M.S.; Fazea, Y. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ learning life: An integrated conceptual motivational model for sustainable and healthy online learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, L.; Reyes, M. Resiliencia y Autoconcepto Personal en indultados por terrorismo y traición a la patria residentes en Lima. Inf. Psicol. 2018, 19, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruíz, C.; Calderón, I.; Juárez, J. La resiliencia como forma de resistir la exclusión social: Un análisis comparativo de casos. Rev. Interuniv. 2017, 29, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz, M.; Muñoz, S. School & famlily in the youngster’s resilience configuration. Rev. Int. Humanid. 2023, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, M.; Becerra, W.V.; Torres, C.C. Resiliencia y edrucación, dualidad conceptual inseparable. Polo Conoc. 2017, 2, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Flórez, L.; López, J.; Vílchez, R.A. Resilience Levels and Coping Strategies: Challenge for Higher Education Institutions. Rev. Elec. Interuniv. Formac. Prof. 2020, 23, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Savitsky, B.; Findling, Y.; Ereli, A.; Hendel, T. Anxiety and coping strategies among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 46, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.; Flores, Y.; Espino, G.; Durán, F. Self-concept, Self-esteem, Motivation, and Their Influence on Academic Performance: Case Study of Public Accounting Students. Rev. Iberoam. Inv. Desarro. Educ. 2021, 12, e015. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, A. Competencias Emocionales y Bienestar Subjetivo en Adultos Emergentes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, S.; Nadal, Á.; Schwartz, S. La integración de la identidad personal, la identidad religiosa y la identidad moral en la edad adulta emergente. Identidad 2017, 17, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreo, E.; Ruiz, L.; Marín, P.; Carrillo, L.; Barriosnuevo, M. Análisis factorial confirmatorio de una escala de autoconcepto para una población universitaria colombiana. Ans. Estrés 2022, 28, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lasarte, O.; Ramos-Díaz, E.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A. Comparative Study between Higher Education and Secondary Education: Effect of Perceived Social Support, Self-concept, and Emotional Repair on Academic Performance. Educatio XXI 2019, 22, 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga, D.; Peláez, S. Autoeficacia y engagement académico en estudiantes. Rev. Dif. Cult. Científ. Univ. La Salle Bol. 2021, 21, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega, G.; Herrera, L.; Montenegro, M.; Torres, V. Autoestima, Motivación y Resiliencia en escuelas panameñas con puntajes diferenciados en la Prueba TERCE. Rev. Invest. Educ. 2020, 38, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, J.; Bruno, F.; Uriel, F.; Fernández, M. Teoría de la Autodeterminación: Una revisión teórica. Rev. Psicol. Cienc. Afines 2017, 14, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Salomón, A.; Martínez, C.; Wren, J. Convertirse en lo que está buscando: Construir la autoconciencia relacional en adultos emergentes. Fam. Process 2021, 60, 1539–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Larruzea, N.; Díaz-Iso, A.; Velasco, E.; Cardeñoso, O. Discriminaciones de género autopercibidas por alumnado universitario de Educación. Escuchando sus voces. RELIEVE—Rev. Elec. Inv. Eval. Educ. 2022, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, C.; Peinado, E.; Solano, N.; Ornelas, M.; Blanco, H. Relaciones entre autoconcepto y bienestar psicológico en universitarios. Rev. Iberoam. Diagnóst. Eval. 2020, 2, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zwane, N.; Mukuna, K. Psychosocial factors influencing the academic performance of students at a rural college in the COVID-19 era. Int. J. Stud. Psychol. 2023, 1, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, P.; Gabriel, A.; Merians, A.; Lust, K. Understanding stress as an impediment to academic performance. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 6, 562–570. [Google Scholar]

- Doménech-Betoret, F.; Abellán-Roselló, L.; Gómez-Artiga, A. Self-efficacy, satis-faction, and academic achievement: The mediator role of students, expectancy-value beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar]

- Expósito-López, J.; Romero-Diaz de la Guardia, J.J.; Olmedo-Moreno, E.M.; Pistón Rodríguez, M.D.; Chacón-Cuberos, R. Adaptation of the Educational motivation scale into a short form with multigroup analysis in a vocational training and baccalaureate setting. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 663834. [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan, D.; Schreier, B.; Gates, C.; Hong, J.; Corkery, J.; Anderson, C.; Keeton, P. The role of mental health counseling in college students’ academic success: An interrupted time series analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2021, 5, 562–570. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, I.; Carolyn, M.; Youssef-Morgan, M.; Marques-Pinto, A. Antecedents of academic performance of university students: Academic engagement and psychological capital resources. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 8, 1047–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero-Ovalle, C.; Madiedo-Parra, M.; Torres-Avendaño, M.J.; Londoño-Salazar, J.; ToroMarin, M.P.; Latorre-Niño, S.; Riveros, F. Relación entre características psicológicas asociadas al rendimiento deportivo, con variables sociodemográficas y deportivas, en una muestra de deportistas colombianos. J. Sport Health Res. 2023, 15, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Quintiliani, L.; Sisto, A.; Vicinanza, F.; Curcio, G.; Tambone, V. Resilience and psychological impact on Italian university students during COVID-19 pandemic. Distance learning and health. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Li, S.; Zheng, J.; Guo, J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25, 1742964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).