Attitude Construction toward Invasive Species through an Eco-Humanist Approach: A Case Study of the Lesser Kestrel and the Myna

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Why Try to Adopt the Eco-Humanist Approach?

4. Research Context—The Lesser Kestrel Education Program

5. The Research Goal and Research Questions

6. Methodology

7. The Research Tool

8. Participants and Data Sources

9. Data Analysis

10. Ethics

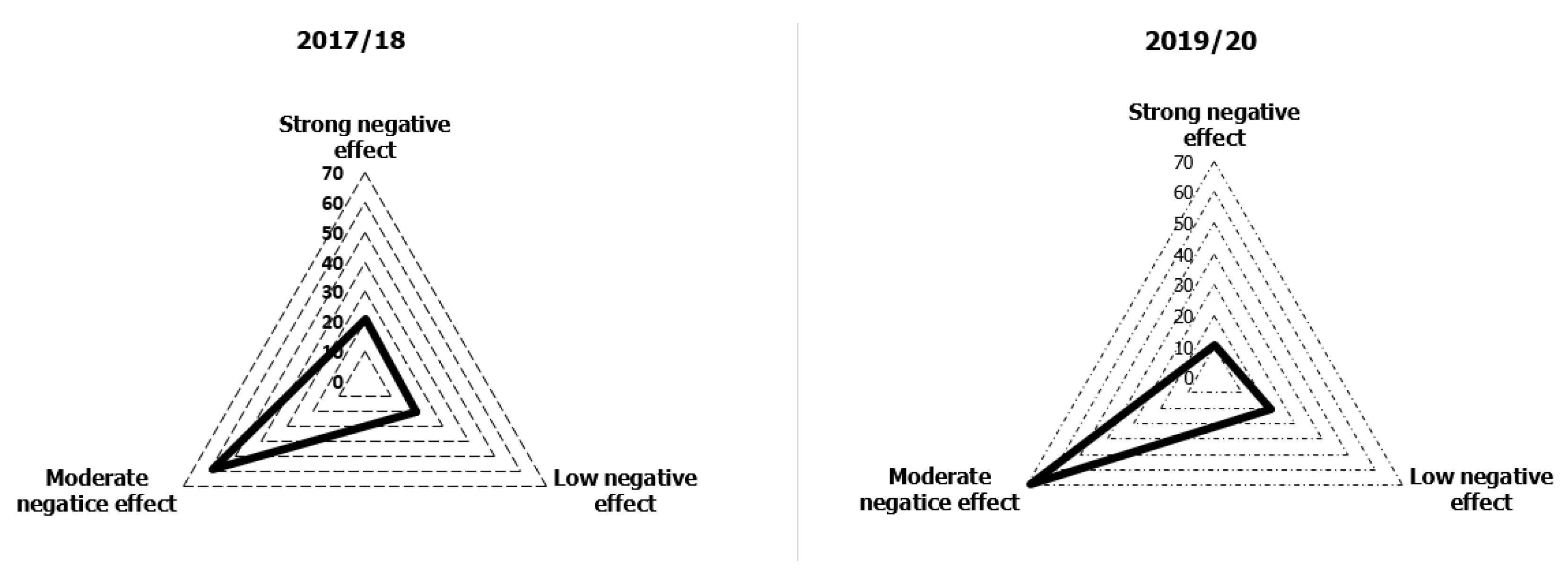

11. Findings

12. The Interaction between the Common Myna and the Lesser Kestrel

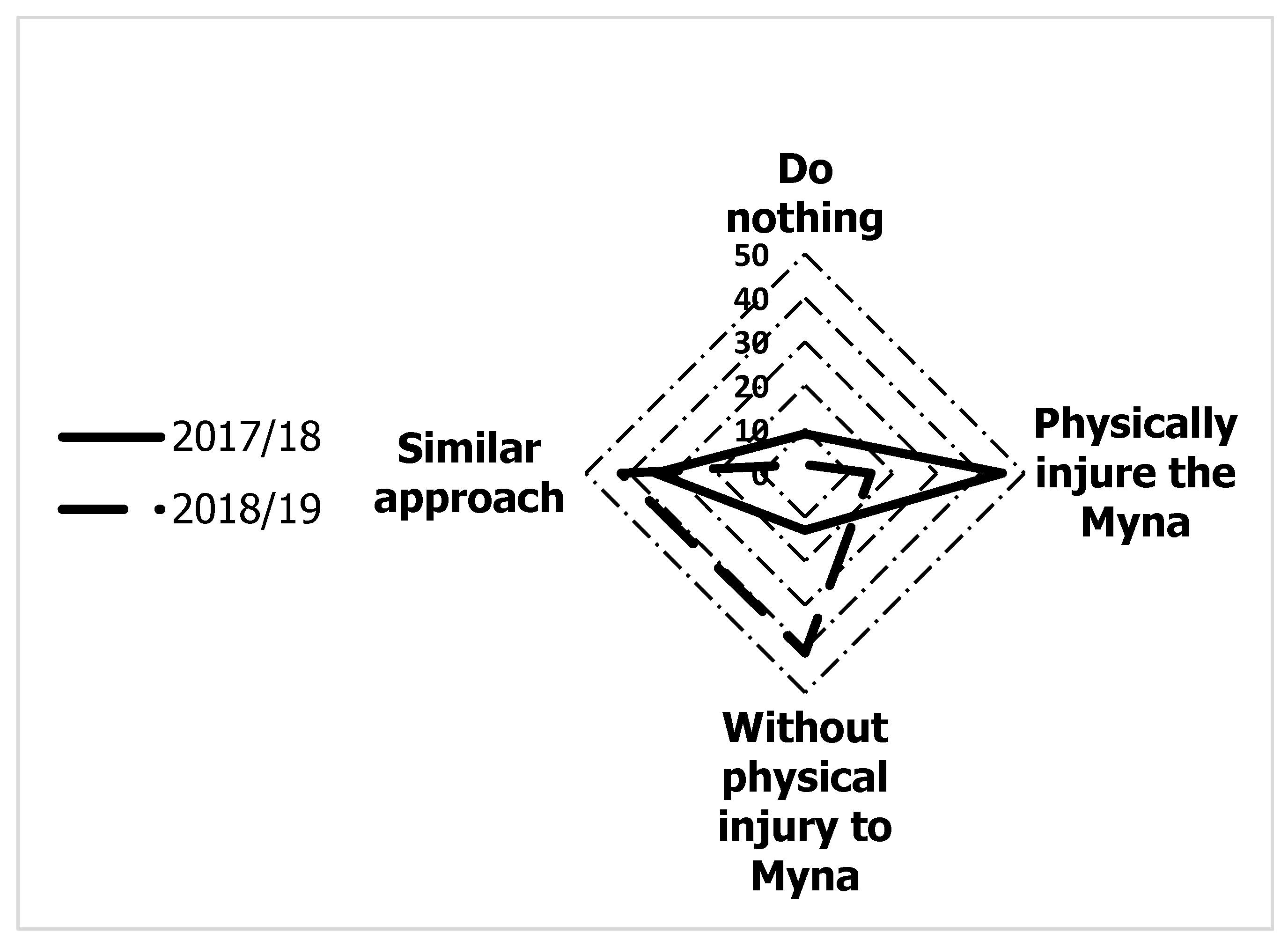

13. Solution of Common Myna’s interaction with the Lesser Kestrel

14. Discussion

15. Conclusions

16. Contribution and Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colléony, A.; Shwartz, A. When the winners are the losers: Invasive alien species outcompete the native winners in the biotic homogenization process. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, M.; Bongers, F.; Martinez-Ramos, M.; Poorter, L. The importance of biodiversity and dominance for multiple ecosystem functions in a human-modifed tropical landscape. Ecology 2016, 97, 2772–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemming, D.J.; Roberts, A.; Diaz-, H. The threat of invasive species to IUCN-listed critically endangered species: A systematic review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Lach, L.; Zuniga, R.; Morrison, D. Environmental and economic costs associated with non-indigenous species in the United States. BioScience 2000, 50, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigall, A.L. Invasive species and evolution. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2012, 5, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cruz, S.; Reynolds, S. Eradication and control programmes for invasive mynas (Acridotheres spp.) and bulbuls (Pycnonotus spp.): Defining best practice in managing invasive bird populations on oceanic islands. In Island Invasives: Scaling up to Meet the Challenge; Veitch, C.R., Clout, M.N., Martin, A.R., Russell, J.C., West, C.J., Eds.; Occasional Paper SSC no. 62.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.C.; Meyer, J.Y.; Holmes, N.D.; Pagad, S. Invasive alien species on islands: Impacts, distribution, interactions and management. Environ. Conserv. 2017, 44, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.J.; Grosholz, E.D. Functional eradication as a framework for invasive species control. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 19, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, D.; Shrader-Frechette, K. Nonindigenous species: Ecological explanation, environmental ethics, and public policy. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, E.C.; Russell, J.C. Ethical responsibilities in invasion biology. Ecol. Citiz. 2018, 2, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, R.; Deck, J.; Guralnick, R.; Baskauf, S.; Beaman, R.; Blum, S.; Bowers, S.; Buttigieg, P.; Davies, N.; Endresen, D.; et al. Semantics in support of biodiversity knowledge discovery: An introduction to the biological collections ontology and related ontologies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, G.B.; Pilon, N.A.L.; Siqueira, M.F.; Durigan, G. Effectiveness and costs of invasive species control using different techniques to restore cerrado grasslands. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, R.; Kowarik, I. Assessing the environmental impacts of invasive alien plants: A review of assessment approaches. NeoBiota 2019, 43, 69–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasetti, P.; Ferrante, L.; Bonelli, M.; Manenti, R.; Scaccini, D.; de Mori, D. Value-conficts in the conservation of a native species: A case study based on the endangered white-clawed crayfsh in Europe. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. Nat. 2021, 32, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, T.B.; Bailey, R.L.; Martin, V.; Faulkner-grant, H.; Bonter, D.N. The role of citizen science in management of invasive avian species: What people think, know, and do. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, S. What’s ontology got to do with it?: On the knowledge of nature and the nature of knowledge in environmental anthropology. J. Political Ecol. 2017, 24, 217–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Addressing the economic costs of invasive alien species: Some methodological and empirical issues. Int. J. Sustain. Soc. 2015, 7, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, A.C.; Venette, R.C. A participatory method for prioritizing invasive species: Ranking threats to Minnesota’s terrestrial ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiralongo, F.; Messina, G.; Lombardo, B.M. Invasive species control: Predation on the Alien Crab Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853) (Malacostraca: Percnidae) by the Rock Goby, Gobius paganellus Linnaeus, 1758 (Actinopterygii: Gobiidae). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, R. No country for possums: Young people’s nativist views. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 35, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.; Pope, J.; Morrison-saunders, A.; Retief, F. Taking an environmental ethics perspective to understand what we should expect from EIA in terms of biodiversity protection. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 86, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.; Blackman, D.; Brewer, T. Understanding and integrating knowledge to improve invasive species management. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 2675–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. Ethics and the extraterrestrial environment. J. Appl. Philos. 1993, 10, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombayci, M.A. Teaching of environmental ethics: Caring thinking. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2014, 15, 1404–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Holzapfel, C.; Levin, N.; Hatzofe, O.; Authority, P.; Kark, S. Colonisation of the Middle East by the invasive Common Myna Acridotheres tristis L.; with special reference to Israel. Sandgrouse 2006, 28, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, S.; Browne, M.; Boudjelas, S.; De Poorter, M. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species. A Selection from the Global Invasive Species Database; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rabia, B.; Baha, M.; Din, E.; Rifai, L.; Attum, O. Common Myna Acridotheres tristis, a new invasive species breeding in Sinai, Egypt. Sandgrouse 2015, 37, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Yom-Tov, Y.; Hatzofe, O.; Geffen, E. Israel’s breeding avifauna: A century of dramatic change. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 147, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Vasconcelos, C.M.; Strecht-Ribeiro, O.; Torres, J. Non-anthropocentric reasoning in children: Its incidence when they are confronted with ecological dilemmas. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T.; Hassan, A.; LePage, B. Environmental ethics: Modelling for values and choices. In The Living Environmental Education; Fang, W.-T., Hassan, A., LePage, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralnik, L.; Nelson, M.P. Anthropocentrism. In Encyclopedia of Applied Ethics, 2nd ed.; Chadwick, R., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralnik, L.; Nelson, P. Field philosophy: Environmental learning and moral development in Isle Royale National Park. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 23, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, K. Environmental ethics: An overview. Philos. Compass 2009, 4, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, B. The war of the roses: Demilitarizing invasion biology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2005, 3, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. Primary school education resources on conservation in New Zealand over-emphasise killing of non-native mammals. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 38, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloni, N.; Gan, D.; Alkaher, I.; Assaf, N.; Bar-Yosef Paz, N.; Gal, A.; Lev, L.; Margaliot, A.; Segal, T. Nature, humans and education: Ecohumanism as integrative guiding paradigm for values education and teacher training. In Field Environmental Philosophy: Education for Biocultural Conservation; Rozzi, R., Tauro, A., Wright, T., Klaver, I., May, R., Avriel-Avni, N., Brewer, C., Berkowitz, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 519–536. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, J. Using a game to teach invasive species spread and management. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 2023, 52, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiulli, K. Teaching invasive species ethically: Using comics to resist metaphors of moral wrongdoing & build literacy in environmental ethics. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 1391–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovid, D.; Phaka, F. Idwi, Xenopus laevis, and African clawed frog: Teaching counternarratives of invasive species in postcolonial ecology. J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 53, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollota, S.; Perez, P.; Allen, J.; Argenti, T.; Read, Q.; Ascunce, M. Are ants good organisms to teach elementary students about invasive species in Florida? Insects 2023, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C.L.; Granek, E.F.; Nielsen-Pincus, M. Assessing local attitudes and perceptions of non-native species to inform management of novel ecosystems. Biol. Invasions 2019, 21, 961–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdourakhmane, N.; Faheem, K.; Arnaud, D.; Francine, P. Environmental education to education for sustainable development: Challenges and issues. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousell, D. Doing little justices: Speculative propositions for an immanent environmental ethics. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1391–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. Sustainable development and environmental ethics. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2019, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, M.J.; James, A. Challenges of taching Akans (Ghana) culturally-specific environmental ethics in senior high schools: Voices of Akans and biology teachers. South Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 36, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, H. Posthumanism or ecohumanism? Environmental studies in the anthropocene. J. Ecohumanism 2022, 1, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, J. Between disgust and indifference: Affective and emotional relations with carp (Cyprinus carpio) in Australia. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2019, 44, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, M. Towards an ecologization of education. J. Environ. Educ. 2019, 50, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merewether, J. New materialisms and children’s outdoor environments: Murmurative diffractions. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, B.; Nerlich, B.; Wallis, P. Metaphors and biorisks: The war on infectious diseases and invasive species. Sci. Commun. 2005, 26, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronlid, D.; Ohman, J. An environmental ethical conceptual framework for research on sustainability and environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 19, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, M.I. Wildlife ethics and practice: Why we need to change the way we talk about invasive species. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2020, 33, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willing, L. Environmental education in Aotearoa New Zealand: Reconfiguring possum-child mortal relations. Child. Geogr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Creating values: The entrepreneurial-science education nexus. Res. Sci. Educ. 2023, 53, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendri, Z.; Rohidi, T.; Sayuti, S. Contextualization of children’s drawings in the perspective of shape and adaptation of creation and the model of implementation on learning art at elementary school. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Iversen, E.; Jónsdóttir, G. ‘We did see the lapwing’—Practising environmental citizenship in upper-secondary science education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matua, G.; Van Der Wal, D. Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Res. 2015, 22, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmawati, Y.; Taylor, E.; Taylor, P.; Ridwan, A.; Mardiah, A. Students’ engagement in education as sustainability: Implementing an ethical dilemma-STEAM teaching model in chemistry learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz, R. An interpretive approach to religious ambiguities around medical innovations: The Spanish catholic church on or-gan donation and transplantation (1954–2014). Qual. Sociol. 2023, 46, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.; Shannon, S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristani, L.; Tomasone, J.; Gainforth, H.; Bassett-Gunter, R. Taking steps to inclusion: A content analysis of a resource aimed to support teachers in delivering inclusive physical education. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 68, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziller, S.R.; de Sá Dechoum, M.; Dudeque Zenni, R. Predicting invasion risk of 16 species of eucalypts using a risk assessment protocol developed for Brazil. Austral Ecol. 2019, 44, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armat, R.M.; Assarroudi, A.; Rad, M.; Sharifi, H.; Heydari, A. Inductive and deductive: Ambiguous labels in qualitative content analysis. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avent, J.R.; Wahesh, E.; Purgason, L.L.; Borders, L.D.; Mobley, A.K. A Content analysis of peer feedback in triadic supervision. Couns. Educ. Superv. 2015, 54, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, C.; Yalamanchili, B.; Fera, J. Climate change on TikTok: A content analysis of videos. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, F.; Samuelsson, I. Preschool children’s agency in education for sustainability: The case of Sweden. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 30, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insch, G.S.; Moore, J.E.; Murphy, L.D. Content analysis in leadership research: Examples, procedures, and suggestions for future use. Leadersh. Q. 1997, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, J.; Östman, L. Clarifying the ethical tendency in education for sustainable development practice: A Wittgenstein-Inspired approach. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 13, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Waliczek, T.M.; Parsley, K.M.; Williamson, P.S.; Oxley, F.M. Curricula Influence college student knowledge and attitudes regarding invasive species. Horttechnology 2018, 28, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haak, D.; Salom, S.; Barney, J.; Schenk, T.; Lakoba, V.; Brooks, R.; Fletcher, R.; Foley, J.; Heminger, A.; Maynard, L.; et al. Transformative learning in graduate global change education drives conceptual shift in invasive species co-management and collaboration. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 1297–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, J. Why is it important to protect the environment? reasons presented by young children. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, K. Reconsidering children’s encounters with nature and place using posthumanism. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 32, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, V.; Blaise, M. Feminist ethicality in child-animal research: Worlding through complex stories. Child. Geogr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before Adoption of the Eco-Humanist Approach | c | Eco-Humanism Principle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogical approach | Biocentric | Eco-humanism | |

| The terminology of the presentation of the Myna | Invader species | A species brought in by people | Dialogical culture |

| Introducing the topic of the Myna to students | Duality between the Lesser Kestrel (positive attitude) and the Myna (negative attitude) | Systemic looking—everyone is equal | Dialogical culture, ecological approach |

| Causes of the problem to the Lesser Kestrel | Myna | Human | Prevention approaches |

| Ecological value | Invasive species have no ecological value, they cause damage | Species transported from one habitat to another by humans have ecological value | Ecological approach |

| Terminology used in lessons to describe the relationship between the Myna and the Lesser Kestrel | Violence, war, struggle, enemy, facing each other, natives versus non-natives, natural versus unnatural, villains, bandits, threat, domination, aggression, exclusion, delegitimization, truth versus falsehood, good versus evil | Completion, inclusion, balance, acceptance, reciprocity, peace, legitimacy, non-hierarchical relationship, perspective of another | Quality of life, dialogical culture, sustainability |

| Mention of evolutionary principles during the lessons | Without reference to the idea of surviving, the invasive species, “aimed at extermination” | An in-depth reference to the idea of surviving | Ecological approach, endurance, and resilience |

| Solution to the conflict between the Myna and Lesser Kestrel | Fast and linear, one-dimensional | Patient, cyclical, multi-dimensional, moral judgment | Ecological approach, endurance and resilience, global patriotism |

| Decision-makers about the future of the conflict between the Myna and the Lesser Kestrel | Only by the teachers | Democratically by student voting | Humanist and democratic ethical, dialogical culture |

| Social influences | Not mentioned social influences | Emphasized social influences while citing examples from the world | Sustainability |

| Emotions towards the Myna | Mostly negative feelings of fear, aversion | Empathy | Slow-paced moderation grants more and harms less |

| Attitudes towards Myna | Attitudes are extremely dangerous from an ethical point of view because it provides people with justification and a sense of moral consolation about killing those who are considered not to belong | A balanced position and ethical examination for harm to living beings | Humanist ethics |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gal, A. Attitude Construction toward Invasive Species through an Eco-Humanist Approach: A Case Study of the Lesser Kestrel and the Myna. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111076

Gal A. Attitude Construction toward Invasive Species through an Eco-Humanist Approach: A Case Study of the Lesser Kestrel and the Myna. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111076

Chicago/Turabian StyleGal, Adiv. 2023. "Attitude Construction toward Invasive Species through an Eco-Humanist Approach: A Case Study of the Lesser Kestrel and the Myna" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111076

APA StyleGal, A. (2023). Attitude Construction toward Invasive Species through an Eco-Humanist Approach: A Case Study of the Lesser Kestrel and the Myna. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111076