Abstract

This paper describes young children’s symbolic meaning-making practices and participation in complex aesthetic experiences in a contemporary art museum context. Through an ongoing long-term research and pedagogy project, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia (MCA) is working with researchers to provide regular opportunities for young children (aged birth–5 years) and their families—all members of the same early childhood education (ECE) services—to encounter art works, engage with materials, and experience the museum environment. The program provides a rich experience of multiple forms of communication, ways of knowing and ways of expressing knowings: through connecting with images, videos and told stories about artists and their practice, sensorial engagement with tactile materials, and embodied responses to artworks and materials. Children also experience the physicality of the museum space, materials for art-making and the act of mark-making to record ideas, memories, and reflections. The project supports the development of a pedagogy of listening and relationships and is grounded in children’s rights as cultural citizens to participation, visibility and belonging in cultural institutions such as the MCA.

1. Introduction

For the past five years, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia (MCA) has collaborated with researchers from the Macquarie School of Education, Macquarie University, on the Art & Wonder: Young Children and Contemporary Art (referred to hereafter as Art & Wonder) research project, illuminating how very young children encounter contemporary art in a gallery space, and how rich pedagogy might emerge from these encounters. The MCA is a not-for-profit organization, collecting artforms including painting, photography, sculpture, works on paper and moving image. The MCA currently holds over 4000 works by Australian artists. The National Centre for Creative Learning (NCCL) was launched by the MCA in 2012, offering arts-based learning to all age groups. In 2016, feeling the need to deepen their pedagogical expertise in the early childhood years, the NCCL approached the university and initiated the discussion that led to the project.

Through this ongoing longitudinal research and pedagogy project, the MCA provides regular opportunities for young children (aged birth–5 years) and their families—all members of the same early childhood education (ECE) service—to encounter art works, engage with materials, ideas, representation, and language, and experience the museum environment. The project has supported a considered reconceptualization of what is possible and what is productive when working with very young children in both the gallery and early childhood education contexts, applying and integrating theory and research findings from across a range of disciplines including museology, child learning and development, visual arts, language, and literacy.

The key overall aims of the research were to:

- (a)

- Explore the impact of actively and regularly welcoming young children, their families and teachers into the context of the public, cultural, creative space of an art gallery—from the perspective of children, their families, their teachers, the artist educators and the museum.

- (b)

- Describe the ways in which young children bring meaning to, and make meaning from, engaging with contemporary art within a museum context.

In this article, we focus on young children’s meaning-making practices and participation in complex aesthetic experiences in a contemporary art museum context. First we will present some examples of children’s responses to repeated museum visits and encounters with artist educators, individual art works, specific exhibitions, spaces, and materials. We then describe how the children’s revisiting and returning to these experiences over time supported the building of connections and establishment of relationships with spaces, materials, artists, and exhibits. We then provide an analysis which explores the question “What could happen between young children and a museum that could not happen anywhere else?” [1] (p. 78).

1.1. Language Development and Arts-Based Experience

The powerful impacts and benefits of creativity and arts-rich educational experiences for young children is well established [2,3]. Play with materials by artist educators, artists and children is a form of abstract and creative thinking and problem solving in a material world. Using rich specialized vocabulary has been associated with later academic achievement, including decontextualized talk [4], complex syntax [5], and academic vocabulary [6]. As children hear more specialized language in context, they are more likely to use and understand it. It also supports more complex understandings of what art is and can be, both in terms of the work of artists and their own artmaking [7]. This is a sophisticated combination of understandings of language and techniques giving the children access to a wide range of symbolic meaning making practices [8].

1.2. Young Children and Art Museums

Museums of any kind are complex spaces, unlike other public and private spaces in their form, scale, practices, and content. Haggard and Williams cited in [9] “suggest that leisure pursuit or informal learning opportunities such as museum visits are important for identity building and enabling people to understand others better” (p. 10). Recent international research has also identified the rich experiences, cultural connections, expertise, authentic learning, and aesthetic engagement that are specific to museum and gallery contexts [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Museology has only lately (in the last 25 years) come to considering young children seriously as agentive museum participants/visitors in their own right, not just as passive members of family groups with adults and older children [17]. Museum research interest in children has tended to focus on school aged children and their learning, usually in the context of family or school field-trip group visits [18].

A museum experience can be a significantly new experience for a young child. Excitement and wonder exists alongside a need for safety, familiarity and attachment [17]. Research involving young children has found they can be unpredictable in terms of their attention and the value they place on the museum itself as a constructed space and place, the conventions of movement and interaction within the museum and their interest in and interactions with exhibits [17,19]. Their responses to the museum can also be quite delayed, arising in conversations and comments weeks after the museum visit [20]. Young children respond aesthetically to the qualities of exhibits in museum collections and to museum spaces themselves [20,21,22]. The opportunity to revisit a museum and its collection, to have time to experience and then re-experience the museum, the collection, ways of knowing and associated language and concepts support the development of schema, those crucial conceptual frameworks that underpin comprehension of texts and experiences in other contexts [17,23].

The contexts of museums and galleries are not always unproblematic places for young children [15,24,25,26]. The visible absence of very young children is apparent in most art galleries and contemporary art museums. Terreni’s research has revealed tensions relating to the (often overt, at other times more subtly implied) exclusion of young children (and their families and teachers) from public museums and galleries. Barriers to participation range from physical access issues to openly discriminatory practices and biases against young children, often founded in deficit-based perceptions of what young children are capable of and where they belong. These perceptions may be held by museums themselves but also by children’s families and teachers [27,28,29].

Collection content, and the practices associated with the care and exhibition of the collection, has also had an influence on research undertaken in museums, in large part because of the perceived relevance of collection types to various audiences. Piscitelli and Anderson’s research [30] with 4–6-year-olds found the children preferred social and natural history museums over science and art museums. These researchers interpreted this preference as being because social and natural history museum collections were more recognisable/familiar to children, founded in life experience. Art galleries have tended to receive less research attention, especially in relation to children as visitors [18] and thus museum based visual arts pedagogy is a neglected area of research [13,26,31]. Such visible absence of very young children may be attributed to children’s age as well as a perceived lack of ability to engage appropriately within the boundaries of socially and culturally acceptable ‘museum art gallery visiting’ norms [15,32].

1.3. Living Literacies Approach

While the Art & Wonder project was not conceived of primarily as literacy focused, the potentials for young children’s learning and development are fundamentally related to language, literacy and meaning making processes. The project sits well theoretically in the Living Literacies approach, drawn from New Literacy Studies, whereby literacy is regarded not as a set of measurable skills but as a social practice, embedded in social groups and situations [33]. The emergence of literacy occurs within the experience of language, objects, materials, spaces and feelings, in both the past, present and future. Memory and reflection act on/with the present moment and the realization of what might be [34]. The approach functions theoretically to support research methods that capture the process of living literacy:

“A living literacies approach is generated through the sites and spaces of the literacy projects undertaken. Collaborative and interdisciplinary by nature, it enables artists, community partners and researchers to work together in a more entangled way while acknowledging and foregrounding expertise that comes from different spaces.”[34] (p. 14)

The Art & Wonder program provides a rich experience of multiple forms of communication, ways of knowing and ways of expressing knowings: through connecting with images, videos and told stories about artists and their practice, sensorial engagement with tactile materials, and embodied responses to artworks and materials. Children experience the physicality of the museum space, materials for art-making and the act of mark-making to record ideas, memories and reflections. The project supports the development of a pedagogy of listening and relationships and is grounded in children’s rights as cultural citizens to participation, visibility and belonging in cultural institutions such as the MCA [28,32]. This has been a collaborative, reflective process between the museum, artist educators, the university researchers, the children, families and ECEC teachers with considerable evolution occurring over time in the processes and experiences being provided to the children.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Program Description

All the child participants (aged birth–4 years of age) were either enrolled at Mia Mia Child and Family Centre or their younger siblings. Planned visits to the museum occurred at eight-week intervals, with a total of four visits over six months, from 10.30 a.m. to 12.30 p.m. The children attended with their family members (for example, a parent and/or grandparent and younger siblings) on a day they were not enrolled to attend Mia Mia. Teachers from Mia Mia also attended. The COVID-19 pandemic had a considerable impact on the program, with no programs being run in 2021. The program was resumed in early 2022, with a new group of child participants and their families.

The visits had the following schedule:

- Meeting artist educators in the MCA foyer

- Walking together to the NCCL

- Settling in, in a circle, welcome with the big pink ball of string

- Listening to an introduction to the artist educator practice and explanation of the focus artist

- Visiting the gallery, seeing focus artworks with the artist educators

- Returning to the NCCL space

- Playing and interacting with art materials in the studio workspace

- Drawing and representing

- Eating lunch together before farewells

Families were given a blank book by the artist educators on the first day of the program, to journal and record any observations, collect anecdotes, photographs, and drawings before and after each visit. This book was called the ‘Special MCA Book’. Children were encouraged and supported to exchange letters with the artist educators between visits. Families were supplied with pre-stamped postcards to which the artist educators responded. This process supported the development of relationships, sustaining their continuity and promoted mark making, reflection on experience and literacy as a social practice.

2.2. Data Collection

The data for this study were generated through three sources:

- (a)

- Photographs: Professional photography was utilized to capture subtle cues, sensory responses and interactions between children, artworks, and others in the MCA.

- (b)

- Artefacts: Children’s drawings, journals, letters, and observations of responses to artworks were included as research artefacts. These represent the constructive process “which purposefully bring shape and order to their experience, and in so doing, the children are actively defining reality rather than passively reflecting a “given” reality” [35] (p. 124). Through this process, children are both knowing reality and creating it to communicate.

- (c)

- Interviews: Separate focus group interviews were conducted with families, Mia Mia teachers and artist educators. The interview questions were open-ended and designed to elicit participants’ perspectives about the MCA program. Sample questions included: Can you please tell me how you are finding the program? Have you noticed any changes with your child over the past few months after visiting the MCA? The emphasis in this question was to elicit a sense of what particular influence the museum experience was providing children and families. These were subsequently recorded and transcribed.

2.3. Data Analysis

Qualitative thematic analysis was utilized, enabling the identification and organization of data themes to facilitate interpretation [36,37]. The focus of the analysis was framed around the question “What could happen between young children and a museum that could not happen anywhere else?” [1] (p. 78). Beginning with the focus group data, each transcription was closely read, seeking patterns and similarities which could inform emerging themes. By using the process of constant comparative reviewing of the data [36], each author independently identified relevant passages in the transcriptions for themes. The statements were then collated and a joint comparison of these by the authors occurred to identify which aspects of the program the participants had explicitly discussed. The second level of analysis involved revisiting the photographs and examining key concepts from these images and comparing with the emerging data.

3. Findings

Two key themes emerged in relation to the language related impact of the Art & Wonder program as it evolved and how engagement with contemporary art in this museum context supported children’s meaning making. Participation was grounded in provision of a shared language for responding to and describing aesthetic experiences and ideas. These provisions were grounded in intentional planning practices, founded on conscious, responsive reflection on the process over time.

3.1. Language for Participation

A key function of language is as a tool for expression and a vehicle for engagement with other people and social institutions, in this case a museum. Artistic knowing and communicating involves a special type of literacy that is as important and complex as spoken and written communication [38]. Children learn artistic discourse through intentional teaching with the artist educators. As Wright [39] explains, “children need opportunities to depict and interpret, which involves sensory, tactile, aesthetic, expressive and imaginative forms of understanding” (p. 5). Children use a range of representational resources which merge and interact to represent the many ways of expressing themselves. Language, however, was a key resource for the children.

3.1.1. Establishing a Sense of Belonging and Confidence

Children and families participated in social routines of informal welcomes on arrival at the museum foyer (Figure 1 and Figure 2), and a formal welcome process in the NCCL and then farewell on departure. This created a feeling of welcome, safety, belonging and connection that supported participation and confidence in both children and adults.

Figure 1.

Welcomes in the MCA foyer and walking together to the NCCL.

Figure 2.

Settling in, in a circle, welcome with the big pink ball of string.

Initially when we all sat down in a circle and passing on the pink giant thread from one person to the other, that exchange in that connection, we all felt the big sense of belongingness in a group and the importance of each and every member of us joining in that one space. Immediately, I think that was really good start. Immediately from that start, we kept on continuing it from there. It was a nice idea to introduce the names and how they can contribute what we thought that can be shared, the ideas. Yeah, it was nice.(Parent)

You can see, you know, the positive attitude that I had which filtered to him, and that made him feel a lot more relaxed and enjoy it too. Yeah, it’s a working partnership, amongst the family members.(Parent)

Families overcame barriers to access and inclusion that traditionally restrict the involvement and participation in public cultural life of families with young children, gaining confidence and increasing cultural capital and creative arts participation for families.

I feel more confident from this experience to revisit again involving the other members [of the family]. It extended into, also, recommending it to our friends and everyone that we know, of such a great experience, enriching experience that we’ve had, as well as not being afraid to join another membership elsewhere because that familiarization, revisiting, just makes it more special.(Parent)

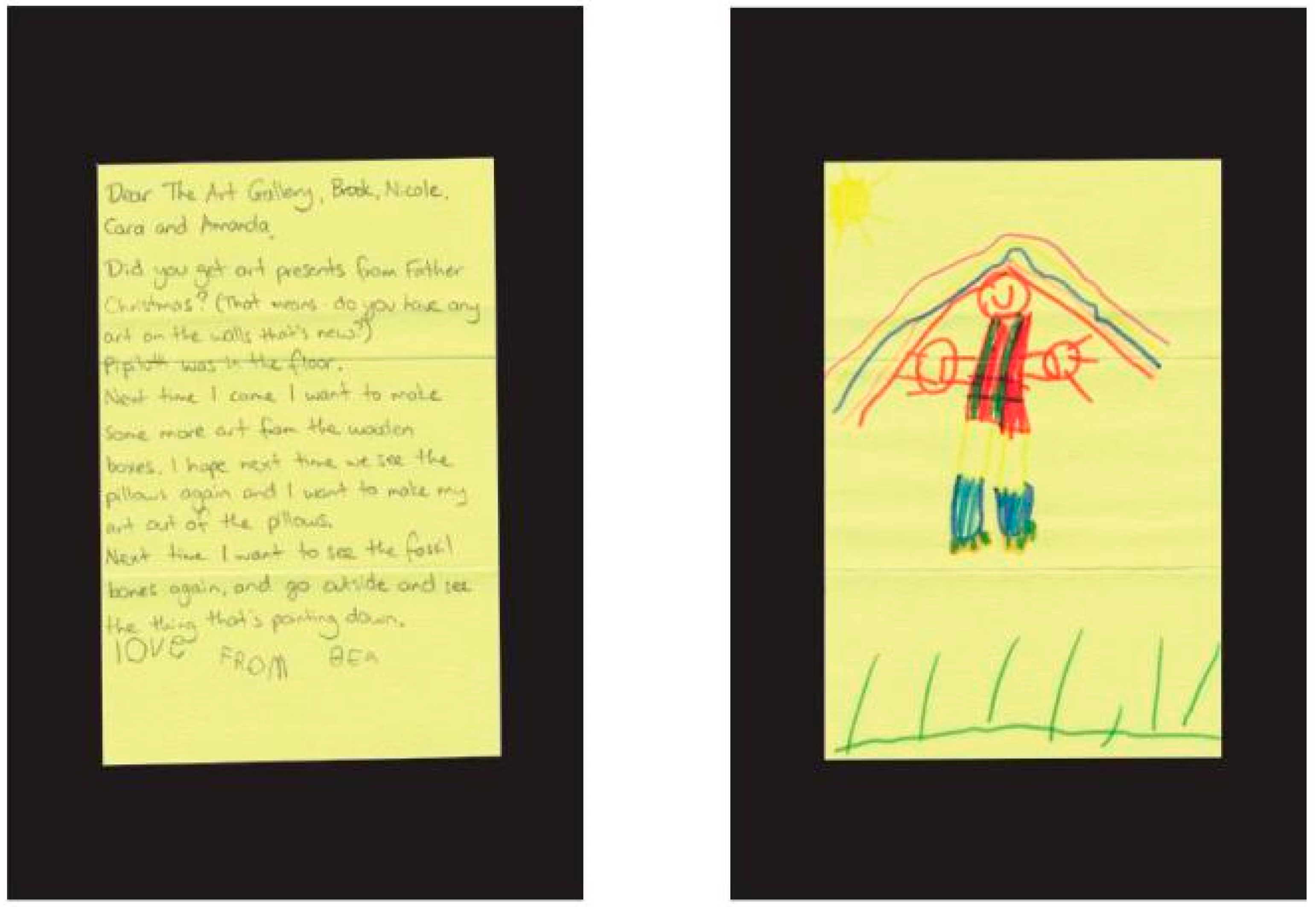

The repeated experience of visits over time, interspersed with letters and postcards (see Figure 3 and Figure 4), supported the further development of relationships between artist educators, children and families and greater depth of engagement.

Figure 3.

Bea’s letter and drawing to the artist educators.

Figure 4.

Letters and postcards.

I think that multiple visits, I think the artists educators developed relationships, knowing the personality of different individual children are going to be like. So, in a group, when we were asked a question and each child had the opportunity to answer, some of the other children were confidently being able to articulate what was on their minds. {Child’s name}, could be a little bit timid, although he had an answer, he didn’t know how to quite voice it, but then when, on a one-to-one basis, when the questions were asked, he was more comfortable to voice out. That was nice, when it was not just all directed in a group, overwhelming, but even like intimate sessions. You know, when he was doing his own water painting, oh, so tell me about what you’re doing {Child’s name}, and he was more able to express and share what he was doing.(Parent)

I think the fact that it was spread out over the period of time it was kind of ... and also with the letters and things they sent and all the back and forth with all the letters and post cards made it so much more meaningful. As I said, spread it out over that period of time, where to start with it was fun and exciting… But by the end it was much more meaningful, and the relationships were meaningful because there was that real connection, on-going connection.(Parent)

A feature of the welcome routine was the use of laminated photographs, to introduce artists and materials and presage what was going to happen across the visit (Figure 5). The photographs also supported explicit discussion of rules and protocols for behaviour and interactions with artworks in the gallery spaces of the museum, in particular the rule of “hands behind your back” (Figure 6). Used in this way, the photographs provided a positive model for children to follow. The photographs were used again in the gallery spaces to remind children of concepts and plans as well as later in the program during the formal farewell to summarize the events of the visit in a manner that supported comprehension, reflection, and confidence in the museum.

Figure 5.

Use of photographs to illustrate artists, visit events and protocols.

Figure 6.

Hands behind your back.

3.1.2. Shared Experience

An unexpected finding was revealed in the parent focus group, highlighting the ongoing impact of the visits to enhance child/ parent relationships and communication:

We could discover it together, and he could see that and for us to both enjoy discovering something new together, regardless of age or theme ... that was very special in that way, where we could prepare, the homework stuff we did, like brought in something from home, we could do that together, prepare together. That was a nice journey, where it was all kind of equal, not age based or ‘mummy has more knowledge than me’. It was just discovering something new together. It was very special.(Parent)

3.2. Intentional Planning and Resourcing for Aesthetic Experience and Response

A key feature of the Art & Wonder project was the intentional planning for aesthetic experience and response, a process that inherently involved language, and the provision of time, space, and a place for deep engagement with language, materials, and concepts. In particular this involved the introduction and explanation of key vocabulary and the description of artworks, processes, materials, thoughts, and feelings. Meaning making by children was supported through opportunities to observe, listen, speak, manipulate artist materials, and make marks.

3.2.1. Dedicated Space (Time and Place)

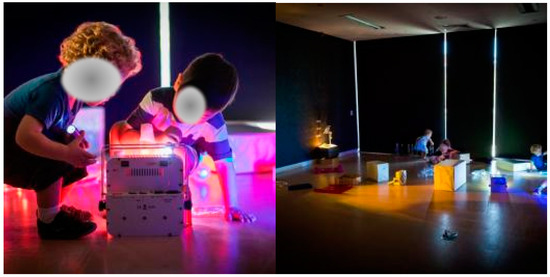

Gallery visiting time included time for children and their families to experience the space and artworks together and artist educator led explanations of key artworks and installations (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Family time in the gallery.

Figure 8.

Artist Educator led discussions about artworks in the gallery.

The conversations and adult-supported observations and explanations in these times were an opportunity for the children to hear and use vocabulary such as painting, collage, tools, installation, and sculpture as well as descriptions of colour, shape, symbols, intentions, themes and meaning that had been presaged in the welcome activities prior. Family members could also relate artworks to children’s known interests, thus building strong contextual and conceptual relationships.

In contrast to the main formal gallery spaces, the Jackson Bella Room is a dedicated space for interactive, multisensory tactile artwork, located within the MCA NCCL and made accessible through artist educator led experiences. Each year, an artist is commissioned to create a new work for audiences to engage with specifically through the senses, including touch which is normally discouraged within the gallery environment. Liam Benson, for example, created Hello, Good to Meet You in 2019 (Figure 9), about horses, their physicality, environment, and social behaviour. The work included video and audio elements and, most notably a giant fringed mane of fabric streamers which almost covered half the room. Benson reflected:

Figure 9.

Interacting with Hello, Good to Meet You (Benson, 2019).

“I love seeing the way children interact with the artwork, particularly the giant fabric fringe mane made up of the spectrum of colours … The children stroked, brushed, flicked, pulled, caressed and held the fabric in a variety of ways. I witnessed expressions of happiness, excitement, curiosity, wonder and sensorial stimulation. The children loved hiding among and behind the mane. Many would find themselves going from a handheld tactile engagement to a full body immersive experience with the mane. It’s joyful to be part of and witness.”

A key element of the program was that there were no expectations placed on children in relation to time or a ‘right’ way to ‘do art’:

… they were given enough, sufficient, ample time to do it. It wasn’t hurried or rushed, okay, soon we’re going to … I mean, it wasn’t like that at all. It’s when the educators and us adults just took a step back and just let them be in charge of their own exploration and you could just see wonderful things from each and every one of the children doing things in different ways, … trying it for themselves. Just thinking creatively.(Parent)

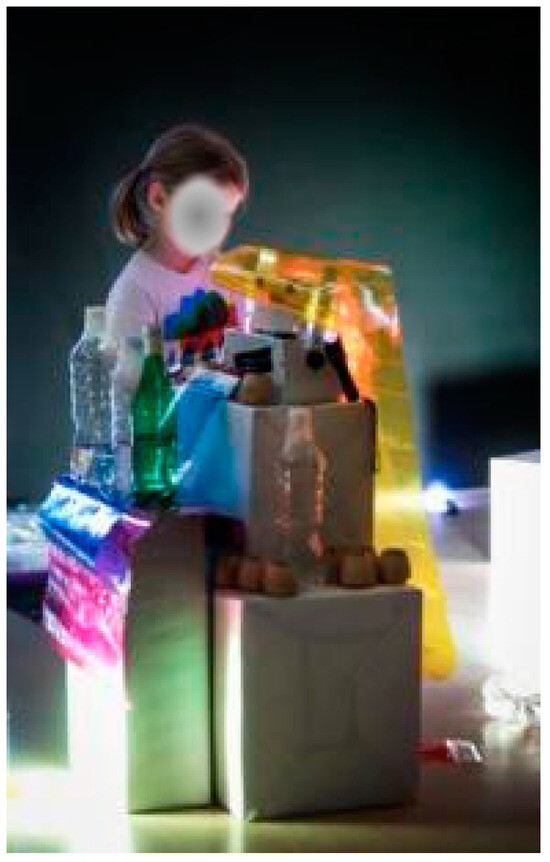

The NCCL studio space was critical for this, where the artist educators provided carefully curated art materials, related to the artworks viewed in the gallery visit. The museum visits provided dedicated space for children and families to interact with the artist educators, with materials in the studio (as diverse as space, light, water, fabric, ‘junk’ including boxes, manufacturing offcuts and organic materials for example) (Figure 10) and the concepts and processes associated with contemporary art.

Figure 10.

Materials for play in the NCCL studio.

… watching them in that space with the water and the light and everything was a real reminder to just kind of let them explore and give them time to explore. Yes, in theory it’s great, and maybe it doesn’t happen so much in practice but for me it was a reminder of that…(Artist Educator)

Play in the studio was routinely followed with a mark-making opportunity, around a shared table with shared materials (Figure 11). This supported the children to make marks on materials provided as well as in their journals. The artist educators joined the children and to observe and interact, share reflections with the children as individuals and in smaller groups (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Mark making together.

Figure 12.

Reflection on journals.

3.2.2. Language of Art-Making and Exhibition

The artist educators shared their own preferred arts play materials and works in progress. scaffolding an understanding of the multiple and diverse voices of the materials they choose to work with. Throughout the Project they have curated the Studio space with materials that provide a glimpse into the exhibiting artist’s assemblages and playful conversations and messages.

The introduction, explanation, and usage of the specific language of art and artmaking is a central element of the Art & Wonder project. Examples of specific language that was introduced to children include terms such as installation and tools.

Recognition that young children experience life and the world using all their senses, but especially touch evolved over several sessions. While many artworks might only be looked at, sensory materials and tools were provided for children to handle with explanations of how they related to the making of artworks, the intentions of artists and how art is exhibited in the museum.

… it was much improved in the third and fourth sessions when they do have something to touch. That made a big difference … it redirected that, you know, quite age-appropriate urge to touch things… So rather than saying no and don’t all the time, I could say yes, but here.(Parent)

Language to describe processes and intentions, feelings was extended as children found ways to explain their responses, ideas and understandings:

Thomas: it looks like treasure -like beads of a necklace.Adi: It looks like rain.Jackson: it looks like a rainbow.Georgia: Glittering.Jackson: It’s shining!Nicole: How do you feel when you look at this artwork?Malachi: I feel calmed down.Nicole: What can you hear?All -I can hear the ocean! -rain -waves -beads falling down -water! water!Georgia: Where are the stingrays going?Malachi: When the rain fell down, the stingrays went away.Adi: I think that stingray is the boss and the others will follow it.Jackson: I think it’s beautiful. All the colours… the rainbow…“Excuse me, Brook? If Abdul Rahman Abdullah comes in the gallery, could you tell him that I love it?” (Adi, 4 years)“Throughout the Art & Wonder project, I have come to be acutely aware of the myriad of connections and threads between the way in which young children experience the world and the way in which many artists work close looking; non-linear, inquiry led investigation; the body and its empathetic sensory experience; making meaning, connections and asking questions, to name a few. As an early learner, meaning is not fixed yet and as an artist we describe the world trying to unravel these fixed definitions and find new ways of seeing the world in which we live. Watching her work on building an installation (Figure 13) or combining materials from different parts of the room is not dissimilar to my own practice as an artist. The outcome is unknown, the meaning can shift and change as the work progresses, the pleasure of testing and transforming materials.”(Artist Educator)

Figure 13.

Art making in the NCCL studio.

Figure 13.

Art making in the NCCL studio.

3.2.3. The Artist

The artist is a figure of some fascination for the children:

“One of the things we learnt early on from the children was when we introduced artists and their practice they needed to know where they were and if they would be coming into the gallery. The artists were real people and they wanted to make a connection to the artist that had made the artwork. We subsequently brought images of the artists to show the children and to introduce them alongside their artwork. I had not seen images of many of the artists myself so I was also making connections alongside the children. The artist image is now a resource available across all our programs and is supported by the artist voice in the form of a quote.”(Artist Educator) (Figure 14) Figure 14. Introducing the artist, Liam Benson.

Figure 14. Introducing the artist, Liam Benson.

Benson was able to physically attend the program and the children responded with eagerness and confidence to share their ideas and art making. Benson felt a connection with the children and admired the confidence he saw in them.

“I also noticed the significance of the newly formed relationship in our free social time within the program. Several children brought their personal art journals to show me their creative process and creations. There was a confident pride in what they wanted to share with me, and I feel this interaction and moment held significance for us because we were connecting as fellow artists and creative makers.”(Liam Benson, artist, see Figure 15) Figure 15. Liam Benson talking with a project participant.

Figure 15. Liam Benson talking with a project participant.

The unique opportunity to encounter not only the photograph of the artist but to meet and engage directly with the artist as he shared his artwork and process with the children was only possible in this museum context.

3.2.4. Children’s Artistic Responses at the Museum and Later

The process of communication between the artist educators and the children became a critical source for understanding the impact of the program on children. Purposeful and authentic reasons for written communication were created. The development of identities as artists, explorations of materials and forms and capacity to explain this was evident:

Yep, so he was kind of using what we had at home, reflecting back to what we experienced at the MCA, just arranging it in a different way. So he would say, oh this is part of what I saw at MCA that I’m going to make my own art. Yeah, so not just always drawing or painting, but actually being tactile and using the resources, which makes art as well.(Parent)

‘I feel like at home {Child’s name} definitely explored more how to be artistic and there was definitely more collage. I emailed you a picture of the sculpture she created out of a plastic bag and some other white things at home, all by herself, and then made it an artwork that I have to hang in the hall.’(Parent) (see Figure 16) Figure 16. Child’s Sculpture (plastic bag and other white things).

Figure 16. Child’s Sculpture (plastic bag and other white things).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The ongoing experience with art, artists, materials and a museum context created by the Art & Wonder program at the MCA has demonstrated firstly the competence of very young children to adapt to museum environments, especially where the museum itself has been prepared to accommodate the needs of young children and their families. Opportunities to revisit the museum, physically but also through the ongoing written communication between the children and the artist educators and reflection in the children’s journals, were emphasised in the data as key factors in children’s engagement, confidence and sense of belonging. The children experienced adults authentically ‘listening’ to their meaning making: the responsive, reflective nature of the artist educators’ engagement with the children gave status to children’s meaning making in its many forms: verbal, visual and embodied. Young children have not necessarily been regarded as welcome, capable and agentive museum visitors (and thus cultural citizens) in the same way as adults and older children [15,16,17,18,25,26,27,28]. The crucial nature of the public, cultural, creative space of the museum environment in this process cannot be underestimated. The proximity of artworks, spaces for viewing and contemplation, the studio and the expertise and knowledge of the artist educators, supported by the early childhood development and pedagogy expertise provided by the university and EC centre educators, synergistically created this learning as noted in other international museum based research [10,11,12,14,15,16].

The techniques and experience developed by the Art & Wonder project, to engage with children and support their engagement with art and the museum, positions the MCA powerfully as an advocate for young children and a source of expertise and models for the inclusion of younger children as legitimate museum and gallery audiences. Artist educators responded to children’s strong desire to form relationships with individuals and supported the children to learn the often-complex cultural protocols of interacting (or not) with artworks at a gallery. The development of this understanding of cultural protocols and living literacies impacts the children, as with these strategies they can move confidently through gallery and museum spaces at the MCA and beyond. It has also had an impact on families, who were surprised and delighted by their children’s competencies and, as a result, have felt a greater sense of confidence in accessing galleries and museums with their young children.

The core, foundational nature of language has been emphasised by the program. Children’s language and literacy development were enhanced while experiences with materials, people and artworks supported children’s understandings of others and the world. Authentic opportunities for exploration provided by the artist educators scaffolded meaning-making in the context of relationships and shared experience. Art & Wonder has contributed to the language development of the children through the provision of key terminology and vocabulary to take and make meaning, to understand and express knowings, feelings and experience and support shared participation at the museum and beyond [7,38]. Arts-based learning provides exposure to and opportunities to use more complex language and access to a wider range of symbolic meaning making practices found to support later learning achievement [4,5,6,7,8]. Art & Wonder is an excellent example of ways that a Living Literacies approach can be utilised to explore and develop authentic literacies embedded in a social grouping where relationships and sharing of ideas, knowings and feelings were valued [33,34]. Children’s experience of multimodal symbolic communication through aesthetic experience with artworks, mark making, movement, photographs of artists, their materials and tools, letter writing and journal keeping all supported emergent literacy. Children were also ‘reading’ cues for museum protocols, for example the white line on the floor in front of artworks. The sensitively guided arts-based experiences enhanced symbolic communication, promoted relationships, developed confidence and supported the communication of ideas and feelings to others.

Future plans arising from this project include initiatives to support connection between early childhood education and care services with museum- and artist-led, rich, arts-based learning across all areas of Sydney and into Regional NSW. At the professional development level, the project provides further impetus to include practical early childhood teacher pre-service and in-service professional development in visual arts pedagogy, and artist educator professional development in early childhood pedagogy.

Limitations

While this research contributes to the growing body of international research on children in museums, there are limitations in this research which need to be acknowledged. The inclusion of only children from Mia Mia families in Sydney, Australia, limits the extent to which these findings can be generalised to both national and international contexts. The funding made available to Art & Wonder that supported, for example, the hiring of a professional photographer for every session is an expense that may not be possible for other galleries and museums. Having a dedicated space where these experiences can be created in studio is another aspect that should also be considered. As further research on children in museums emerges, future research will be needed to continue exploration of artist educators’ understandings and observed practices across diverse contexts and ways in which the complexity of arts education can be seen as integral to professional pedagogical practice.

Author Contributions

All authors made a substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition of funding; contribution to the literature review; and the writing or revising the paper for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Medich Foundation, directly the Museum of Contemparary Arts, Sydney.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Macquarie University, (Approval Number 5201925417398, 1 September 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all adult subjects, for themselves and on behalf of their children. This written consent included the use of images to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the following contributions from the research team: Amanda Palmer Museum of Contemporary Art; Clare Britt former staff member Macquarie University; Wendy Shepherd former staff member Macquarie University; Janet Roberston former staff member Macquarie University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hackett, A.; Holmes, R.; MacRae, C. Introduction to Part II: Museum spaces. In Working with Young Children in Museums: Weaving Theory and Practice; Hackett, A., Holmes, R., MacRae, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R.D.; Gorton, R.L.; Pinciotti, P.; Sachdev, A. Promising findings on preschoolers’ emergent literacy and school readiness in arts-integrated early childhood settings. Early Child. Educ. J. 2010, 38, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R. Creativity: A reaffirmation of its place in early childhood education. Curric. J. 2000, 11, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D.K.; Smith, M.W. Preschool talk: Patterns of teacher–child interaction in early childhood classrooms. J. Res. Child. Educ. 1991, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Share, D.L.; Leikin, M. Language impairment at school entry and later reading disability: Connections at lexical versus supra-lexical levels of reading. Sci. Stud. Read. 2004, 8, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D.K.; Porche, M.V. Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth-grade language and reading abilities. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.D.; Garnett, M.L.; Velasquez-Martin, B.M.; Mellor, T.J. The art of Head Start: Intensive arts intgration associated with advantage in school readiness for economically disadvantaged children. Early Child. Res. Q. 2018, 45, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, L.; Whiteman, P. Literacy, music and the visual arts. In Literacies in Early Childhood: Changing Views, Challenging Practice; Makin, L., Diaz Jones, C., Eds.; MacLennan & Petty Pty Ltd.: Eastgardens, NSW, Australia, 2002; pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin-Philips, J.; Paki, V.; Fruean, L.; Armstrong, G.; Crowe, N. Exploring te ao Maori: The role of museums. Early Child. Folio 2012, 16, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Piscitelli, B.; Weier, K.; Everett, M.; Taylor, C. Children’s museum experiences, identifying powerful mediators of learning. Curator 2002, 45, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, A.C. Powerful allies: Arts educators and early childhood educators joining forces on behalf of young children. Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 2017, 118, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Bell, H.; Collins, L.; Spencer, A. Young children’s experiences with contemporary art. Int. J. Educ. Through Art 2018, 14, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danko-McGhee, K. First encounters: Early art experiences and literacy development for infants. Int. Art Early Child. Res. J. 2016, 5, 1–12. Available online: https://www.artinearlychildhood.org/content/uploads/2022/03/ARTEC_2016_Research_Journal_1_Article_1_Danko_McGhee.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Piscitelli, B.; Penfold, L. Child-centered practice in museums: Experiential learning through creative play at the Ipswich Art Gallery. Curator 2015, 58, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreni, L. Beyond the gates: Examining the issues facing early childhood teachers when they visit art museums and galleries with young children in New Zealand. Australas. J. Early Child. 2017, 42, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weier, K. Empowering young children in art museums: Letting them take the lead. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2004, 5, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, A.; Holmes, R.; MacRae, C. Introduction. In Working with Young Children in Museums: Weaving Theory and Practice; Hackett, A., Holmes, R., MacRae, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Andre, L.; Durksen, T.; Volman, M.L. Museums as avenues of learning for children: A decade of research. Learn. Environ. Res. 2017, 20, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, C.; Hackett, A.; Holmes, R.; Jones, L. Vibrancy, repetition and movement: Posthuman theories for reconceptualising young children in museums. Child. Geogr. 2018, 16, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R. A Vision of History: Young Children’s Perspectives on a Museum. In Children and Childhoods 1: Perspectives, Places and Practices; Whiteman, P., De Gioia, K., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2012; pp. 151–186. [Google Scholar]

- Danko-McGhee, K. Favourite artworks chosen by young children in a museum setting. Int. J. Educ. Through Art 2006, 2, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkins, S.; Tunnicliffe, S.D. Nature tables: Stimulating children’s interest in natural objects. J. Biol. Educ. 2007, 41, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C. Role of the reader’s schema in comprehension, learning, and memory. In Theoretical Models and Processes of Literacy; Alvermann, D.E., Unrau, N.J., Sailors, M., Ruddell, R.B., Eds.; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Terreni, L. Children’s rights as cultural citizens: Examining young children’s access to art museums and galleries in Aotearoa New Zealand. Aust. Art Educ. 2013, 35, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreni, L. Eyes-on learning: Very young children in art galleries and museums. Early Educ. 2015, 57, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreni, L. Young children’s learning in art museums: A review of New Zealand and international literature. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 23, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellet, M.; Robinson, C.; Burr, R. Images of childhood. In Doing Research with Children and Young People; Fraser, S., Lewis, V., Ding, S., Kellett, M., Robinson, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow, C.; Brennan, M. Interrupting dominant images: Critical and ethical issues. In Resistance and Representation: Rethinking Childhood Education; Jipson, J.A., Johnson, R.T., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Qvortrup, J. Childhood matters: An introduction. In Childhood Matters: Social Theory, Practice and Politics; Qvortrup, J., Bardy, M., Sgritta, G., Wintersberger, H., Eds.; Avebury: Aldershot, UK, 1994; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Piscitelli, B.; Anderson, D. Young children’s perspectives of museum settings and experiences. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2001, 19, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, B.; Smith, B. Infants, toddlers and contemporary art: Bright and Shiny research findings. In Proceedings of the Third International Arts in Early Childhood Conference, National Institute of Education Singapore, Singapore, 4–6 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, J. Museum spaces and experiences for children: Ambiguity and uncertainty in defining the space, the child and the experience. Child. Geogr. 2018, 16, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, B.V. Literacy in Theory and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl, K.; Rowsell, J.; Collier, D.; Pool, S.; Rasool, Z.; Trzecak, T. Living Literacies: Literacy for Social Change; MIT Press Academic: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, S. Intention and meaning in young children’s drawing. J. Art Des. Educ. 2005, 24, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In The Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick, M.E.; McKay, R.A. Researching literacy with young children’s drawings. In Making Meaning. Constructing Multimodal Perspectives of Language, Literacy and Learning through Arts-Based Early Childhood Education; Narey, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S. Ways of knowing in the arts. In Children, Meaning Making and the Arts; Wright, S., Ed.; Pearson: Frenchs Forest, NSW, Australia, 2012; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).