Abstract

There are several models for e-service learning, from traditional (without any online content) to extreme online service learning (without any actual interactive elements) which suggested by L. S. Waldner. In Type III, (hybrid) e-service learning, the instruction or service can be offered partially onsite and partially online. Waldner cites four successful case studies to prove such a model can work. Teachers should prepare students to participate in service learning during other disasters that may occur anytime, and offer servification dimensions for teaching. Using the Waldner Type III model, this paper aims to promote and stimulate service learning in shelters, as well as onsite and online, for the adoption of animals. Considering this paper is the leading research on the project’s application, we employ a qualitative research method, observing the students’ reflection work to clarify the basic proposition, and to describe what happened when we changed the model of hybrid e-service learning from Type III to Type I during the epidemic.

1. Preface

This article discusses the process of service learning (SL) practiced through action research at Fu-Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City in Taiwan, during the COVID-19 epidemic. This study adopts an action research model, hoping to solve two problems faced by the author in teaching onsite SL. The first problem is that students are not interested in SL. Service learning has been implemented at Fu-Jen Catholic University for many years. In the implementation, in addition to being able to combine with professional courses or school-defined core courses, SL can also be taught as a stand-alone course. However, students were not interested in SL and found it troublesome because of the inappropriate methods they had experienced before in high school, or because of the misunderstanding shown by their seniors. This can be seen in their experience with students’ dissatisfaction with SL as shared on an online forum called Dcard in Taiwan. For example, on 11 April 2018, a student coming from Fu-Jen University posted a story on Dcard titled “Stupid Service Learning” (https://www.dcard.tw/f/fju/p/228667873, accessed on 1 June 2022); he complained about the distress SL was causing him. Some other students also thought that SL was just volunteering work, or that it was a waste of time and life. This article is still there, at the end of July 2022, and we can find some similar articles there today. We can also see similar reports in the news. For example, in a 2 February 2021 report, a study by a civil society group pointed out that less than 20% of students in SL in Taiwan believe they have learned something [1]. The second problem is the disruption caused by COVID-19. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, many SL courses have been canceled. Since SL is a helpful learning model for students, can we lead students in a more flexible way? For this purpose, this paper examines the conducting of hybrid e-service learning (eS-L), which is being employed in the Philosophy of Life course, and the model of action research, to determine whether this method of SL can improve the attitudes of students, and whether it provides the teachers with more flexibility.

2. Literature Review

As we already know, SL is a common mode of instruction and is associated with experiential education [2]. Beginning with John Dewey, SL is a learning process that combines learning with hands-on experience. Thus, Dapena, et al. argued that SL is an approach to teaching and learning that allows students to provide service to the community while gaining competency in the curriculum [3]. This statement is also consistent with J.C. Kandall’s description of service learning as a program, a philosophy, and a pedagogy [4]. In the context of higher education, SL emphasizes that college students validate what they have learned in the classroom through experience by actually participating in community service activities. Not only the actual experience, but also the different reflective works such as writing and report compilation, integrate the relevance of what they have learned to the real world [5]. With this goal, MaCarthy argued that learning in SL can be classified as a triangle built on experience (doing), reflection (learning), and knowledge (thinking) [6].

In recent years, due to technological advances and the epidemic, scholars have begun to move SL from face-to-face to online delivery. As we have seen, the discussion in the literature on eS-L can be divided into two main parts: research on the practice of eS-L, and the demands of eS-L.

2.1. Research on E-Service Learning in Theory and Practice

Regarding eS-L, the Practical guide on e-Service-Learning in response to COVID-19 published by the European Association for Service Learning in Higher Education in 2020 cites Waldner, et al. and Manjarrés Riesco, et al. as defining eS-L as follows: “e-Service-Learning (electronic Service-Learning—eS-L) or Virtual Service-Learning (vSL) is a Service-Learning course mediated by information and cmmunication technologies which the instructional component, the service component, or both occurs online, often in a hybrid model” [7,8]. According to the definition given by EASLHE, eS-L is still a type of SL, but uses the Web as a tool in part or in whole, or has the Web as a scope of service. Additionally, according to Yusof, et al., service learning can be divided into traditional SL, in which both service and learning are face-to-face, or that based on the degree of dependence on technology, such that SL is fully virtual [9]. Both service and learning can be either onsite or virtual tech-based SL, and whether it is service or learning, both are virtual extreme SLs (vSL/eS-L). In this action research, we adopted the second option and adopted a course content that was partly face-to-face and partly virtual, regardless of service or learning. By eS-L, here, we mean that for the service objects, we used any suitable software and hardware to complete the SL.

The operations in our courses are based on those of Waldner, et al. [10]. Research about online SL appeared as early as 2010. According to Waldner, et al. [8], SL content can range from traditional (without any virtual content) to fully online (without any onsite elements, which is called extreme e-service-learning (xSL)). Waldner cites two case studies to demonstrate that xSL does work. Waldner, et al. later proposed a further theoretical study on eS-L and divided eS-L into four categories [8]. Among them, Type III (hybrid) e-service learning can be partly onsite and partly online, providing guidance or service. Waldner’s model became the basis for later studies. For example, Jill Stefaniak also divided eS-L into four categories [11].

2.2. Demands for E-Service Learning

Before the COVID-19 epidemic, many scholars had noticed the advantages of eS-L and tried to practice it in school. For example, Branker, et al. in 2010 tried to enable engineering students to use SL for businesses by promoting Green Information Technology through the internet [12]. They believed that this would help students apply their learning on the one hand, and help companies fulfill their social responsibility on the other. After the epidemic, the implementation level of SL has been affected; we observed that more and more implementing institutions or schools have been studying how to continue SL in a situation that may at any time be interrupted by external factors that prevent us from doing our job properly. In such a situation, teachers should be ready to help students continue to participate in SL throughout various types of disasters, and provide the required teaching. In response to this situation, many schools and institutions began to implement SL during the epidemic. For example, the topics of the academic seminars held in 2021 and 2022 by the Service Learning Inter-School Alliance Service in the Northern District of Taiwan were related to the epidemic. The 2021 symposium also included several papers and keynote speeches on eS-L [13,14].

Many studies have revealed the actual situation of eS-L. Kenji Ishihara and Hitomi Yokote provided an overview of the theory and practice of eS-L in their paper “Reflection on Online Service-Learning at ICU” [15]. Based on their teaching experience of leading students to conduct hybrid SL (partly online and partly face-to-face) during the epidemic at Tokyo International Christian University in Japan, they discussed how to maintain SL through technology during the epidemic, as well as the problems arising from online SL, including over-reliance on internet technology, the lack of actual interaction, or the presence of students who may have insufficient learning experience to discuss. Michael J. Figuccio highlighted that eS-L can eliminate the limitation of physical space and reduce the anxiety of students when participating [16]. Moreover, compared with onsite service, students are more satisfied with themselves under these conditions. M.E. Schmidt led a team of students in a child psychology course on service learning, and observed that students may have lacked face-to-face experience during the process, but they still highly identified with eS-L [17]. The scholars also noted that eS-L was conducted in relation to an operation system. Dapena, et al. used the Microsoft 365 system, which is commonly used by students for SL, and monitored the students’ status during SL through the system’s monitoring function [3]. They also created a webpage related to SL so that participants could access SL-related information and content at any time.

In fact, eS-L has become a mode of operation recognized by official organizations. As we have said, the handbook Practical Guide on e-Service-Learning in response to COVID-19 was published by EASLHE in 2020 to support the continuation of service activities. In Chapter 3 (pp. 23–35 of the book), it is suggested that the standards for operating eS-L should be compared to the requirements of traditional SL in the past, except that these requirements are achieved in a digital environment [7]. The chapter also gives advice that should be heeded in areas such as technology, communication, and teaching. This guide also provides operators with 23 different communication software programs, and gives directions for the use of and practical help for eS-L.

2.3. Analysis of the Literature Review

Observing the research on eS-L, Marcus, et al.’s research results concerning eS-L in the paper “A Systematic Review of e Service Learning in Higher Education” made observations and suggestions [18]. After sifting through 97 results from two journal databases and finally selecting 20 of them for research, they noticed that most of the research papers, in terms of methodology and research design, typically used cases as research objects, followed by mixed methods, action research or qualitative research. They noted that, while many teachers who engage in lectures are concerned that switching from traditional to online training will create barriers to delivery, many studies have shown a trend toward eS-L, regardless of the challenges teachers may face in eS-L, or in helping students to reflect. For example, they cited Guthrie and McCracken’s paper, suggesting that reflection journaling is an appropriate tool to prevent teachers and students from lacking the teamwork relationship that traditional school services have when adopting eS-L. In the words of the Marcus team, “students were empowered to assess their own individual learning goals and collaborate with others to make meaning of their service learning experience. Reflection process is so much easier and richer with the use of technology in e-Service Learning platform. Students that were involved in eS-L also reported a strong sense of learning from the open discussion”. That is, no matter how advanced the technology, one of the important purposes of SL is guiding students to achieve learning outcomes through experience and reflection.

In addition, the earliest papers discussing eS-L are more likely to mention technical issues, especially the performance of the equipment and the user’s operating familiarity [8,10]. Although the former has been rarely mentioned in recent years, this problem still exists in the field of SL; the latter problem only continues to appear in a different form due to the continuous innovation of communication software. The internet has become more convenient, and it is beneficial to eS-L; however, there is too much communication software to choose from, which creates different problems for users. For this reason, what software should be used for eS-L becomes a new question. Dapena, et al. used the latest operation system, Microsoft 365, and the handbook of EASLHE manual lists the most readily available software [3,7]. However, the software that is needed not only matches what kind of software is available at the time (for example, FB already existed in 2010, but it may not have been used), but also includes the learning objectives and service items when eS-L is carried out.

We also noticed that most of the research on eS-L was mainly targeted at humans; as B. Jacoby stated in his definition of SL, in the action of SL, students work for the needs of humanity and communities, such that they can learn from structural reflections—there are almost no cases about animals or other entities as the service objects [2]. However, since one of the important purposes of SL is to allow students to gain valuable learning experience through practice, a variety of service methods should be considered and planned as the content of the lesson plan.

3. Operating Procedures

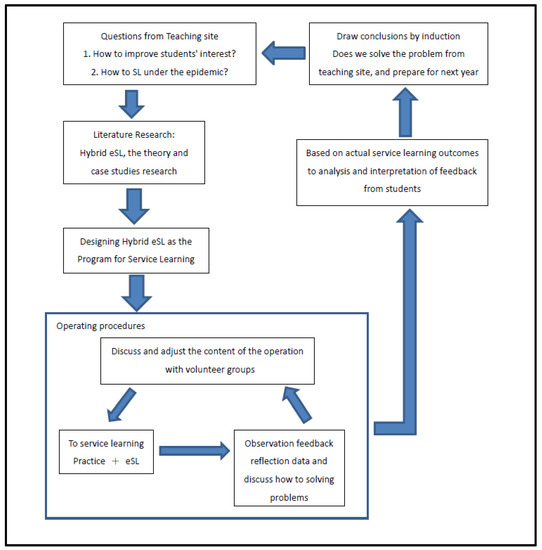

The purpose of this action research is to verify that the hybrid eS-L can improve students’ attitudes towards service, and give teachers more flexibility to respond. The action research undertaken in this paper dates back as far as the beginning of the 2020 epidemic, when the author discussed with volunteer groups how SL should be sustained during the epidemic. After discussion and experimentation with different approaches, it was decided that we would continue the SL in 2021–2022 through an eS-L process, identified through a collaborative design process. To determine the appropriateness of this approach to address the questions raised in the introduction, we conducted observations through this action research, focusing on the flexibility of the process to address the questions and the ability of students to develop a correct understanding of dog limb signs through the process. The implementation time of this action research was from September 2021 to May 2022. Based on Ming-Lung Wu and Zeng-Tsai Cheng, we designed this process as shown in Figure 1 [19,20].

Figure 1.

The research process.

3.1. Implementation Object of Hybrid E-Service Learning

To verify the practicability of the hybrid eS-L, we chose two classes for implementation: both classes were part of the Philosophy of Life course, and the implementation methods were all designed as a one-time program with exploration value as the focus of development. According to Liu Xing-yuan, et al., this design emphasizes the collaborative and mutually beneficial relationship between the class and the service organization, allowing the organization to participate in the coordination of the course content and allowing students to become the manpower required by the cooperative organization [21].

Philosophy of Life is a required course at Fu-Jen Catholic University in Taiwan. The goal of the course is to help students understand their place in a changing environment through philosophical reflection, develop a harmonious relationship with God and people, and develop a respectful and loving view of life through multiple thinking, problem-solving, reflection, and communication. We chose to use the animal shelter for SL because, on the one hand, it could be combined with one of the course modules to facilitate a 5- to 8-week-long SL activity, and on the other hand because Taiwanese students, although easily exposed to dogs, often have many misconceptions about dogs, and are exposed to danger due to misunderstanding their body language (for this reason, an animal semiotics perspective needs to be introduced in the course). So, in practice, students can improve their understanding of dogs through the sensory experience of an actual shelter [13]. The students were able to gain a practical understanding of the substance of Taiwan’s animal protection policies while serving as the manpower needed for volunteer groups. Of the classes we chose, one was part of a day school (58 students in this class) and the other came from the department of advanced studies (25 students in this class). Both classes implement the Philosophy of Life course, which is in the curriculum as a compulsory subject at Fu-Jen Catholic University. The Philosophy of Life course is the core course of the Fu-Jen University, and the course duration is two semesters. One of the common themes during the two semesters is “Environmental Change and Development”, and the implementation is based on this unit.

According to Waldner, et al., the hybrid eS-L we used should belong to Type III: the original design was intended to teach and give feedback to volunteer groups both in the classroom and online, and to promote animal adoption online in addition to serving in the shelter [8]. In fact, the second semester implementation was biased towards Type I. This is the result of adjustments made by the authors and the volunteer organizations, because the epidemic disrupted the original plan. All students completed the training face-to-face in the classroom, but when it came to the actual service, many of them switched to the online service due to the epidemic.

3.2. Animal Protection and Service Learning in Taiwan

We integrated SL with animal protection in our curriculum, which is related to the educational environment in Taiwan. The educational system in Taiwan provides students with service learning in shelters to further their life education; this is the context in which our study was conducted. This model of education has been in place thanks to government agencies. The Taipei City Department of Animal Protection, for example, has a special section on their website to provide students with SL opportunities (https://www.tcapo.gov.taipei/cp.aspx?n=64E92A82C8BB7529, accessed on 1 June 2022). In addition to government agencies, schools in general also lead students in SL through education models related to animal protection, or to life education. For example, Pei Shan Peng and Nicco Hsieh reported that students studying management used their profession to convey the importance of bonding, emphasizing the need for adoption instead of purchase, and promoting dog shelters [22]. Chung Yuan Christian University is just one of many examples. In fact, many other schools in Taiwan also conduct SL related to shelter entry or animal protection. Although entering a shelter for SL or life education is a part of our education, entering a shelter for SL is still considered risky.

The above-mentioned government agency wrote on the volunteer recruitment document that “the nature of the animal home service is special, and students who wish to participate in short-term public service volunteering should first obtain the consent of their school or parents”. (Italics added for researcher’s emphasis.) This is because the service includes closeness to animals. In addition to their special nature, these service opportunities have been suspended for a period of time due to the epidemic. Therefore, animal protection and service learning can be combined with each other in Taiwan, but in practice, suitable partner organizations are needed to facilitate the curriculum and avoid restrictions when students are looking for them on their own.

3.3. Cooperative Institutions

The non-profit cooperative organization used in this research is “看見 Seeing” (meaning “seeing” in Chinese), a long-term volunteer group dedicated to promoting animal adoption in shelters in Taiwan. The organizations that we work with in the course are the ones that the researcher visited and agreed to work with. Its main job is to increase the exposure of the dogs in shelters, because shelters in Taiwan are mostly outlying and set up next to landfill sites, resource recycling plants, or cemeteries. Taiwanese people dislike approaching these places, and the shelters’ locations are not easy to access, making adoption difficult. Hence, the volunteer group invites the public to walk into the shelters with them, take pictures of the dogs, and write posts, then post pictures and words on the official fan page or the public’s own messaging apps to increase the chances of the dogs’ adoption. In order to provide students with the services they need, the group usually visits classrooms to explain the current state of animal protection in Taiwan, teach the proper treatment of dogs, and lead students into shelters to learn about the shelter environment and dog walking (and when circumstances permit, lead students to give medication or bathe their dogs). With this foundation, we can ask students to complete the production and promotion of the video. This has been set up because environmental policies in Taiwan have changed dramatically in the past 10 years, such as with the elimination of euthanasia for unowned animals.

We hope that through this service learning activity, students will appreciate that dogs and other animals do live around us, and can live with these animals in the right way. In the course, when students enter the shelter to help care for the dogs, they realize the value of life on the one hand, and the need to interact with others in the process of caring for them, including volunteers from volunteer groups, shelter staff, and other people who come to the shelter. In other words, although dogs do not talk, our students are giving these dogs a voice through SL and online advocacy.

3.4. Cooperation Mode

Previously, teachers and the cooperative organization have mutually cooperated on a semester-by-semester basis, and usually complete two sessions of service learning in 1 year. For the college year 2021 to 2022, the process of adjustment to hybrid eS-L for the class is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The procedure of how to facilitate e-service learning with the Seeing Group.

The purpose of adopting hybrid eS-L is to verify in the action research that this mode of service can give more flexibility to teachers and students and can cope during an emergency situation such as the epidemic. According to the plan in Figure 1, the first round of execution would be from September to December 2021, and the second round would be from March to May 2022. The service content is planned as follows:

- The pre-trip training is conducted face-to-face, and the teachers from the cooperative organization will attend the classroom to give the training to the students;

- The SL is divided into two parts in a hybrid eS-L. The first involves visiting the shelter in Wugu Dist. and taking pictures or videos of the dogs while assisting with walking them. Although there were more than 100 dogs in the shelter, we selected 8 dogs with the most stable and gentle personalities for our students. If the dogs were unstable or aggressive, our students would have been at greater risk. We also wanted to focus the students’ attention on these eight dogs when promoting adoption to increase their chances of being adopted. The second part is online promotion; the students edited the photos into a 30–60 s promotional video, which was posted on personal social media to promote the shelter and dogs;

- Reflection and feedback will be conducted online first. After the students reflect on visiting the shelters and the online promotion in the form of homework, they will share videos at a lunch party at the end of term, and invite the teachers from the cooperative organization to the class to give feedback.

3.5. Evaluation Method

We evaluated student learning outcomes by giving students the work they needed in a variety of ways over a 5- to 8-week period. The service and reflection reports that students are required to complete during the two semesters are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Work to be completed by students during service learning in both semesters.

We asked the students to make a video to promote the dogs. This service was designed this way because of the remote location of the shelter and the difficulty of promoting adoption, as expected by volunteer groups. Through the study, we also hoped that the students would come to understand the policy of animal protection in Taiwan and the practical difficulties and realities of public service promotion. After the production of the video was completed, and with the approval of the whole group, the video was handed over to the Seeing Group for further promotion on their official FB and IG.

As regards the student reports, in the first semester, after the students had completed their first sessions of onsite SL, they were asked to complete a key event form to reflect on their feelings about their first time in the shelter through different dimensions. During this time, the students spent two weeks discussing, creating and completing a video for online promotion; the video was intended to act as an introduction to animal adoption at the shelter. The video was promoted through their personal SNS (some of them created IG fan pages after discussing with their teacher) for a period of 2–3 weeks. After completing the online promotion, students submitted a 4F reflection report before the end of the semester, reflecting on their experiences and learning from this time, both in terms of onsite service and online promotion.

In the second semester, our original plan was to complete the 4F reflection report within one week of completing the first onsite SL. Due to the epidemic, some students were not able to finish, but moved directly to the extreme eS-L. Although the students who switched to eS-L did not enter the shelter, the promotion of adoption is part of the Seeing Group’s work, and was also part of the students’ SL, so we still required the students to complete the online promotion and 4F reflection report. In addition, the students were also asked to compile a report to discuss their observations on online promotion. Finally, the students were asked to complete a reflection at the end of the second semester comparing what they had done in the two semesters. This final reflection was the basis for this study. Through the students’ reflections of the two semesters, we can note what the students experienced or learned through the service learning process. The content of this assessment was only based on students who had completed SL in both semesters. The reasons for this will be explained below.

4. Effectiveness and Responses

The teacher conducted hybrid eS-L in the Philosophy of Life course with two classes from September 2021 to May 2022. During the two sessions, problems were encountered during the learning process, which required solving. The following discusses the difficulties and solutions, as well as the feedback and reactions of the students, to illustrate the effectiveness of this action research.

4.1. Difficulties Encountered in Implementation and the Solutions

For the first time in the two implementations, students in both classes completed the onsite pre-trip training and the SL. They also conducted the publicity on their personal communication platforms, or on a community platform specially established for publicity and adoption after completing the promotional video. The problems encountered in this onsite service included that the number of people visiting the shelter was limited, meaning the two classes were divided into four groups to visit the shelter on four different Saturday mornings.

When we entered the shelter, we encountered an unexpected problem. In Taiwan, both universities and high schools need to conduct SL activities; high school students are required to apply for further education and college students are required to undertake club activities or course requirements. During the epidemic, onsite SL was suspended and could not be implemented. Hence, when the epidemic subsided, many schools would send students to complete SL as soon as possible. At the shelter, we met more people than expected. However, dogs have a sense of territory and protect their food, so when there are more people than dogs, the dogs can feel threatened and even attack. When we encountered this situation for the first time, we staggered the timing of taking the dog out of the cage, allowing the teachers of the volunteer group to maintain a safe distance between the different animals at the scene, and adjusted our time so that the students could complete the reflection, and take photos and video. This became our standard operation mode for the next three sessions.

The problem encountered in the first online service was that the students were not familiar with online marketing. Although students often use communication software and are familiar with advertisements on the internet, when each team was asked to produce a promotional video, they were not familiar with how to do so. After feedback was given by the students, the teacher announced the marketing method and scope on the course platform and in the classroom, and stipulated that students do not need to spend extra on publicity (and also stated that the numbers of views or KPIs would not be included in the final grade assessment). With clearer norms and explanations, each team could start successfully promoting adoption online.

The second implementation session was mainly concentrated from March to April 2022. The two classes were originally scheduled to visit the shelter for onsite SL in three periods. The implementation focused on this period because the weather in Taiwan had become significantly warmer since May. The shelter was located in a mountainous area, and hence the SL attendants were prone to encounter poisonous snakes, and for safety, we hoped to complete the onsite SL before the weather warmed up. In response to the publicity problems encountered in the previous semester, the teachers adjusted their responses in the second semester as follows: shortening the film production time, giving clear publicity guidance, including publicity channels, and a clearer start time for publicity. Compared with the previous semester, the two classes in this semester improved significantly; for example, it was possible to discuss with the teacher whether the use of the IG stories would have a more significant effect than directly posting them on FB, and pay more attention to the content of the video’s layout and arrangement.

4.2. Changes Due to the Epidemic

We encountered a resurgence of the epidemic in the second semester in Taiwan, in 2022. At the end of April 2022, the number of confirmed cases in Taiwan exceeded 10,000 in a single day. With the premise that students had not been protected by vaccines and that many students on campus had been diagnosed, the students in the classes were worried about onsite service. After discussions with the cooperative group and obtaining the approval of the course provider in university, the teacher changed the services of some students from hybrid eS-L; that is, all students completed the onsite training and the SL part was changed to eS-L (Type I in Waldner, et al.’s classification). Finally, the first onsite SL in March was successfully completed, and other SL sessions in April were changed to online. Although the Taiwanese government had not officially decreed that face-to-face activities could not be conducted at that time, the author and the group decided to switch from onsite to online activities in order to prevent the possibility of students contracting the disease during the service.

There was also a time coordination problem with the two implementations: the date of the onsite service had been determined and announced at the start of the school term, but because the service was conducted on Saturdays, some students could not attend due to work and courses. The flexibility of the hybrid eS-L can be seen here; by changing to a fully online service (which Waldner called extreme E-service learning), students who could not be present could still participate. The methods included assisting students to edit videos, assisting in publicity, or individuals completing animal health promotion videos through research.

Compared to the original program, some students lacked onsite SL experience after changing to extreme eS-L. We understood the importance of students’ actual participation in SL. This includes participation, behavior, exploration, etc., which is all related to the actual experience [23]. Although most of the students had actually entered the shelter in the first semester, did the students have different reflections on the lack of practical experiences in the second semester? This depends on our observation of the students’ reflective work.

4.3. Classification of Observation Object Student Group

To determine the effectiveness of hybrid eS-L, we only evaluated the reflection reports of students who had taken this course in two semesters, since Philosophy of Life is a two-semester course. Some students only take one, and although these students also completed at least one SL session, they were not included in our observation. We selected students who took the course in both semesters because they had experienced the hybrid eS-L in the first semester, and nearly two-thirds of them switched to extreme eS-L in the second semester due to the epidemic, so we could compare whether their feelings and attitudes were different between the two semesters. In particular, students who took the course in the second semester had no experience with onsite SL, so they could only give their predictions about onsite SL, or recall the experiences of onsite SL of other students. A total of 75 students met the observation criteria. The distribution is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The distribution of students.

Based on two semesters of SL, we can further divide the students into three categories of observation:

- *

- Category 1—33 students completed both onsite and online hybrid eS-L in both semesters;

- *

- Category 2—Only in one semester was onsite and online eS-L completed; the other semester was fully online. The two classes had a total of 37 students. In addition to the epidemic, three students switched to online SL in the first semester due to illness or car accidents;

- *

- Category 3—The two semesters comprised fully online SL. There were only five students in the two classes, all of whom came from night school.

4.4. Outcome Analysis

Focusing on the students in the three categories above, we observed their reflections and feedback related to the last semester; we also referred to the other five reflection assignments they completed over the two semesters. In the first semester, in addition to giving publicity results in groups, students also filled out the key event form and final reflection. The second semester was the same, except for the statistics of the publicity effect. The students participating in the service, whether in a hybrid form or online, were required to write a 4F reflection, and compare their personal growth and reflections between the two semesters. The following describes the results of the students’ reflections according to time and different aspects.

5. Reflective Analysis for the First Semester

In the reflection report of the first semester, most of the students were surprised by four aspects: remote location, inconvenient transportation, unpleasant smell, and the loud dog barking. The first two relate to the fact that the transportation took extra time, and the students responded that although local taxis or Ubers were booked, the bookings were canceled because the location could not be determined by GPS. More than half of the students mentioned the last two problems in the shelter, or the problem of urination and defecation caused by the relaxation of the dog when it came out. These reactions are real, and these experiences are also necessary because if there is no actual visit to the shelter site, it is easy to have illusions about the current situation of animal protection. By the end of the first semester, the total cumulative views for each group were around 1500. This is the result of the limitation of marketing without funding.

6. Reflective Analysis for the Second Semester

Through the experience of the previous semester, students began to have a deeper affection for dogs in the second semester. In the first category, where the two semesters used hybrid eS-L, 4 out of 33 students focused on the specific emotional connection with a certain dog (unfortunately, because there were many dogs in their families, the dogs could not be adopted by them); in the second onsite service, the feeding of heartworm medicine and food was increased. Seventeen students specifically mentioned this in their reflections on the contact trip, and another six students specifically mentioned their feelings after entering the kennel. All the students who visited the scene twice showed a different emotional connection to the dog from before they went, and three students, in particular, expressed very sad feelings in their reflections.

As regards the second and third categories, that is, the students who completed the hybrid eS-L at least once, and the students who undertook the whole online service for two semesters, 18 of the 37 students in the second category directly expressed their feelings about the absence of onsite service with negative emotions, including feeling “pity” and “disappointed” about not being able to make it to the scene. However, most of the students understood that it was due to weather factors and the epidemic. In the teams who came from night schools, 10 of the 13 students who had undertaken onsite service expressed their desire to arrive at the shelter rather than complete online service. Most of them said that they would feel empty and lack much valuable experience if they did not experience the onsite service. This mirrors what Barbara Jacoby mentioned about the limitations of this type of service [2]. In the third category, one out of five students who took courses entirely online also expressed their willingness to visit the site rather than work online. As for students who preferred online to onsite courses, the main consideration was related to the location: “the transportation is inconvenient”, and “it takes a lot of time for traffic”.

If we compare these three categories of students, we find that students who have already visited the shelter will tend to continue to visit onsite rather than complete online service. We reasonably speculate that this is because the experience brought about by the scene is irreplaceable online. Through the actual interaction with animals, the students regained their expectations for SL, and believed that it would be helpful for them to learn the proper way to get along with animals. However, as we have already noted, Michael J. Figuccio mentioned in his research that students’ satisfaction with the course and themselves after participating in eS-L is significantly higher than that in onsite learning [16]. This phenomenon is also reflected in our action research. Here, we can refer to the section below; students found themselves with increased potential when comparing between the two semesters. These are not contradictory, because online SL requires improving one’s ability, while, according to Figuccio’s research, students’ participation in SL activities reduces anxiety.

7. The Promotion of Effectiveness

One of the projects of this eS-L is to promote dogs for adoption on the internet. Comparing the two semesters, the students in the second semester started to focus on the publicity channels, and could indicate the number of different publicity channels in their assignments. In the second semester, the online publicity channels of the students were FB, IG (including stories), and YouTube, these being the media most commonly used by students in their daily life. As mentioned, when the SL in the first semester went to the online promotion stage, because the students did not know how to operate and lacked the concept of publicity, at least three teams specifically asked what should be done. In the second semester, when the students were familiar with the ways of publicity and its operation, they could clearly see the difference in the number of publicity channels: the two classes in the last semester had a total of about 1500 views, and it was not easy to distinguish the number of views on each channel at that time. In the second semester, the students were able to clearly distinguish the relevant information advertised on the internet and even discuss about what they should do for future publicity. Here are three examples:

- *

- Day school team 1—Self-analysis is “49 views of IG stories, 40 likes, and 5 comments from friends on the post. In the discussion part, in terms of marketing without funding, the reach of a single post is acceptable. Almost all of them are viewed by peers or acquaintances, and the exposure is very limited”.

- *

- Day school team 2—Self-analysis is “Compared with the previous semester, this semester was unable to go to the site for service and study due to the epidemic, but because we couldn’t go to the scene, saw us promote ‘how to get along with dogs’ by editing videos. The process I also discussed with the team members, what editing techniques to use to increase the number of views of the film, which also taught me a lot of editing tips”.

- *

- Night school team—Self-analysis is “Because I didn’t participate in the dog walking activity this time, I can’t compare it with the last dog walking experience. I think the dog walking activity is not only interesting but also meaningful. On the one hand, you can interact with cute dogs; on the other hand, you can also gain additional benefits, such as learning about the habits of dogs, or knowing that dogs also have different characters. Before walking the dogs, the teachers delivered a very complete course, which can be said to have no shortcomings. In addition, although the repercussions of our promotional video are not as ideal as we imagined, knowing that I have also done my part for these furry children, I am very happy”.

8. Comparisons of Two Semesters for Personal Reflection

Through the comparisons of the two semesters, students can observe and propose their own changes. In this last reflection on self-change, the students gave feedback. Based on the students’ responses, we can summarize the following points that most of them mentioned—some students mentioned more than one item at a time, while others focused specifically on one of the items:

- *

- Thirty-five students said they discovered self-potential through varied types of SL, including making videos, walking the dogs, and developing new abilities;

- *

- Forty-two students said they had learned how to get along with dogs, get close to dogs through practical operations, develop feelings for dogs, or, having been afraid of dogs, can now overcome such difficulties;

- *

- Twenty-two students said they had real experiences of the problems of dog shelters and an understanding of the current problems encountered by animal protection in Taiwan;

- *

- Twenty students said that they recognized the hard work of animal protection volunteers;

- *

- Twenty-six students said they had learned the skills of online promotion and video production;

- *

- Eighteen students said that they will do something for the dogs, including give their support and continue to spread the word online. If they have the opportunity, they would like to bring their friends to visit the shelter.

Based on the content of the students’ final reflection assignments, we noted that they were consistent with the triangle for learning in SL mentioned in MaCarthy, as cited earlier [6]. What we provided in the classroom is only knowledge about animal protection policies and animal behavior; it may or may not be related to students. Through actual experiences in shelters and online advocacy, as well as through reflective assignments, students were able to assimilate this knowledge into what they learned. MaCarthy’s triangle begins the discussion with experience because experience is how students gain additional opportunities in real-world service actions. However, experience and knowledge complement each other: MaCarthy said knowledge makes experience meaningful, while knowledge without experiential support is only abstract. Experience and knowledge can be combined in a reflective process into what the student actually learns.

As such, from the analysis of the above aspects, we can first notice the effects of changes in SL itself on the students. Students may erroneously feel that SL is just “going somewhere to do service for someone whom I do not know”; they do not know what SL really entails, and they think that SL is only for children, elders, or friends who are disabled. However, when the course took dogs as the service object to experience the preciousness of life, and after training, serving, and reflecting through the complete learning process, the students responded positively to the service study, and the majority of them began to like the visits and completing the onsite service. Second, the way the hybrid eS-L can really help us deal with emergencies was confirmed by the rapid adjustment of schedules in the author’s class when faced with a COVID-19 outbreak. Through two semesters of practical operation and correction, the students not only gained basic and correct knowledge of animal semiotics, and the methods of online publicity and video production (the learning part), but they also experienced online promotion with volunteer groups (part of the service).

9. Conclusions

From September 2021 to May 2022, the teacher conducted two hybrid eS-L sessions in the classroom, although the second one was due to the epidemic, and some students changed to full online SL. We also set up an online celebration and reflection in June 2022 for students who finished all the work after two semesters. Through this action research, our conclusions regarding hybrid eS-L are as follows:

- The advantages of hybrid eS-L enable teachers and cooperation partners to grasp the progress and content of SL and make timely adjustments, even if they may not be able to continue. In early April 2022, the COVID-19 epidemic in Taiwan re-emerged. Initially, universities only took up e-learning as a precautionary measure. However, after mid-May, the Ministry of Education allowed all universities to teach remotely until the end of the academic year. The teacher and the leaders from the Seeing Group team immediately discussed and made decisions through the LINE group to determine what should be done if the government raised the alert level, and how to finish the work if it was impossible to conduct activities. Even though the teachers could transform SL into the extreme mode, hybrid eS-L can also allow teachers to conduct SL due to weather conditions;

- Hybrid eS-L has the ability to increase learning motivation for students. In addition to the specificity of the objects, hybrid eS-L allows students to gain experience of onsite SL as well as online, offering a service with diverse dimensions. Hybrid eS-L allows students to experience the work aspect of animal protection from different perspectives, and can also break the stereotypical conceptions students have of SL. This is what we saw in the articles of K. Ymamoto and MaCarthy [5,6]. In the study by M.E. Schmidt, which we mentioned earlier, he also mentioned that eS-L can provide students with more flexibility to use SL in their own way, and eS-L can also reduce students’ anxiety in SL, as implied by the study by Michael J. Figuccio [16,17];

- The target class of this action research contained both day and advanced students. Although their identities and backgrounds were different, there was no difference in their learning, performance, and work required for the study; they accomplished the same work goals and produced quality results, even if their class times were different or even limited. Hence, it can be seen that hybrid eS-L plays a substantial role in the teaching application.

Funding

The cost of the service, data collection and APC is partly subsidized by Fu-Jen Catholic University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Due to the anonymity of this study, the data will not reveal the personal characteristics of the students, and because this study is based on a discussion of teaching methods, an IRB is not required.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y.-N. Civil society group: 50% of youths like service learning, only less than 20% acquire professional knowledge. United Daily News, 2 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, B. Service-Learning Essentials: Questions, Answers, and Lessons Learned; Chinese Edition; Liu, R.L.; Guo, W.Y.; Qiu, J.H.; Wang, M.H.; Liu, F.; Qiu, X.Q., Translators; Pro-ed: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dapena, A.; Castro, P.M.; Ares-Pernas, A. Moving to e-Service Learning in Higher Education. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, J.C. Combining Service and Learning: Am Introduction. In Combining Service and Learning: Aresource Book for Community and Public Service; Kendall, J.C., Ed.; National Society for Internships and Experiential Education: Raleigh, NC, USA, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kazu, Y. What is “Service Learning”. In Service-Learning Studies Series No. 1: Introduction to Service-Learning; Service Learning Center, International Christian University: Tokyo, Japan, 2005; pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- MaCarthy, F.E. Educating the Heart: Service Learning and Shaping the World We Live. In Service-Learning Studies Series No.1: Introduction to Service-Learning; Service Learning Center, International Christian University: Tokyo, Japan, 2002; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- EASLHE. Practical Guide on e-Service-Learning in Response to COVID-19; EASLHE: Flemish Region, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Waldner, L.; McGorry, S.; Widene, M. Extreme E-Service Learning (XE-SL): E-Service Learning in the 100% Online Course. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 2010, 6, 839–851. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, A.; Azean, N.; Harun, J.; Doulatabadi, M. Developing Students Graduate Attributes in Service Learning Project through Online Platform. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bangkok, Thailand, 5–7 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Waldner, L.; McGorry, S.; Widene, M. E-Service-Learning: The Evolution of Service-Learning to Engage a Growing Online Student Population. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2012, 16, 123–150. [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak, J. A Systems View of Supporting the Transfer of Learning through: E-Service-Learning Experiences in Real-World Contexts. TechTrends 2020, 64, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branker, K.; Corbett, J.; Webster, J.; Pearce, J.M. Hybrid Virtual- and Field Work-based Service Learning with Green Information Technology and Systems Projects. Int. J. Serv. Learn. Eng. 2010, 5, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, D.-Y. Service Learning for Good Dogs: Execution Strategies from Onsite to Online. In Proceedings of the 13th North District Service-Learning Cross-School Alliance Service-Learning Symposium—Awake: Service-Learning Challenges and Responses for COVID-19 Epidemic Prevention, Taipei, Taiwan, 15 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-P. Love Uninterrupted Power: Online Overseas Service Learning under the Epidemic. In Proceedings of the 13th North District Service-Learning Cross-School Alliance Service-Learning Symposium—Awake: Service-Learning Challenges and Responses for COVID-19 Epidemic Prevention, Taipei, Taiwan, 15 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, K.; Yokote, H. Reflection on Online Service-Learning at ICU; Service-Learning Studies Series No. 6; International Christian University, Service Learning Center: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Figuccio, M.J. Examining the Efficacy of E-Service-Learning. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 606451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.E. Embracing e-service learning in the age of COVID and beyond: Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. Int. J. Serv. Learn. Eng. 2010, 5, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, V.B.; Atan, N.A.; Yusof, S.M.; Tahir, L. A Systematic Review of e-Service Learning in Higher Education. Ternational J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2020, 14, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.-T. Action Research: Principles and Practice; Wunan Books: Taipei, Taiwan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.-L. Introduction to Action Research in Education: Theory and Practice; Wunan Books: Taipei, Taiwan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-Y. Service-Learning Program Design. In Learning from Service: Interdisciplinary Service Learning Theory and Practice; Hungyeh: Taipei, Taiwan, 2009; pp. 131–224. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, P.S.; Hsieh, N. Listen to what the students have to say about the current situation of the homeless dogs—An interview with the Department of Information Management “Management” Service Learning Program. Chung Yuan Christ. Univ. Serv. Learn. 2021, 41, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Lin, Z.S. Basic Concepts and Theoretical Foundations of Service Learning. In Learning through Service: Theories and Practice of Service-Learning across the Disciplines; Hung, E., Ed.; Hungyeh Books: Taipei, Taiwan, 2012; pp. 19–59. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).