1. Introduction

Play is important for children; it is where they explore, try out new things, and voice their opinions. It is a vehicle for nurturing their interest and provides a platform for exploring curiosity and creativity [

1]. Children’s active engagement in play supports their cognitive and physical development as they bring what they already know to their play and build on or experiment with their knowledge and understanding. Children also enter play situations with experiences from home, their family, and community [

2]. The combination of children’s social interactions and bringing their own understanding and interpretations of the world provide an irresistible foundation for creativity, exploration, and curiosity. Coupled with this, the environments children encounter and are able to engage with further compound the desire for children to play and imagine.

The empowerment framework (EF) [

3] is a tool for capturing children’s involvement in their play environment and with their peers. It exposes what they are interested in and how they are learning through that process. The EF was designed as a conceptual framework, developed through PhD research with seven case-study children and families. This paper reports on a small-scale study of practitioners in the UK using the EF for the first time in ‘real time’ practice. The challenge of the EF is that it requires a shift in thinking from recording

what children do or achieve to

how children do something and how they interact with their environment and those around them. It is based on three guiding themes of participation, voice, and ownership, which are significant in contributing to empowering experiences. Under these guiding themes, practitioners are asked to think about open-ended prompt questions when they are observing children and to consider how children are playing through an empowerment perspective.

1.1. Empowerment

The term empowerment is an elusive concept. It is often defined in relation to business or community action rather than Early Childhood [

4]. Yet empowerment is a fundamental quality that most individuals desire. It is complex because people do not feel empowered all of the time, it is a process or a feeling, and requires certain elements to be in place for empowering experiences to occur [

3]. Although other approaches to early years education contain the sentiments of empowerment such as Reggio Emilia in Italy and Te Whariki in New Zealand, they are centred around their own cultural identities. Carr’s learning stories offer an approach to assessment which gives a voice to young children though assessment that can shape learning and reflect pedagogical thinking [

5]. In the same way this research puts children’s empowerment as the most significant element for observation and a foundation for understanding an individual child. A framework based on the core elements of empowerment can transcend different cultures, contexts, and circumstance in the same way that Carr’s learning stories developed an approach to assessment. A framework concentrating on what it is that significantly contributes to a child’s engagement is valuable in furthering understanding about the way in which children learn and develop.

Empowerment in children’s play follows an argument that it is not one single action, event, or circumstance. It is concerned with examining individual choices and decisions based on social interactions, emotional responses, and environmental influences within situated boundaries and resources. However, there are essential components that contribute to children’s experiences of empowerment: these are Participation, Voice, and Ownership.

1.2. Participation

Participation in play is significant to the process of empowerment because the nature of participation shapes and directs what is happening and can potentially change or develop children’s interests or build capacity for on-going play [

6]. How children decide to participate in play is significant. They may negotiate their way into a play situation or be more assertive through taking the lead and instructing other children. They may challenge themselves through pushing their physical limits or encourage other children to try something new in order to sustain a play situation. Children may use their initiative to change a game, or focus of play, to ensure it continues. Becoming involved in established play is also an emotional risk children take in joining in for the first time or expressing their interest in case they are rejected by the group. Active participation requires being involved, by investing in social interactions with others and risking an emotional investment in caring about what is going on and wanting to be part of that situation [

7]. However, active participation can also imply empowerment of those involved in the sense ‘that children believe and have reason to believe that their involvement will make a difference’ [

8] (p. 111).

Participation is more than expressing individual choice and is part of a broader experience of belonging and feeling valued [

9]. Thus, children in play may become powerful social participants in their own right as play allows them to express their preferences and interests. Where these are accepted by other children, this signals that their views are important [

7]. Participation, therefore, has a wider meaning in that it is not just about the connections children make with their peers; it is also about children being able to make choices and having opportunities to be curious. It also supports pathways for children to explore and feel included or wanted as part of play. In its widest sense, participation is significant to the process of empowerment because motivation for being part of play comes from the child and subsequently can be sustained for as long as children’s interests remain active.

1.3. Voice

Through play children have opportunities to observe behaviour, copy each other, see how others respond to them and those around them and deal with others’ expectations and feelings, however these are expressed [

10]. In this paper, children’s voice is defined as the way in which children explore how they can express their views not only through speaking but through their actions, body language, gestures, or where they position themselves within a group of children [

11]. In child-initiated social play children have certain choices in what they do as well as what they choose not to do which demonstrates to other children their preferences and how strongly they feel about them [

12]. Children can also manage other children’s responses not only to their verbal communication, but their actions and consequences of their actions [

13].

Children’s spoken voice does not always reflect the reality of their experiences; what children say is not always the whole story of what they want or need [

14]. Often children’s voice is examined within the context of adult–child relationships [

15]. However, children’s voice is also relevant in child–child relationships and particularly in play situations where children may demonstrate different social and emotional skills in using different modes of expression effectively. Expressing an opinion amongst other children who also have opinions requires confidence and self-assurance, especially in a large social group. Through different ways of communicating with their peers, and having their opinions valued and heard by others, children are more willing to contribute their thoughts and ideas, not only by what they say, but also by what they do [

7,

16].

Empowerment in children’s play manifests itself through children expressing their point of view in agreement or if it differs from others; and using different modes of expression to show their preferences [

17]. This may be through making decisions about the materials or resources they want to play with, the space they want to play in, and the timing of their play. There is an interconnectedness between children’s voice and participation in play, as the more children want to be involved, the more opinions they have about the direction of their play. This also supports the process of creativity and imagination where all forms of communication between children is important for play to evolve, be negotiated and contain a certain amount of compromise so that everyone involved achieves a sense of satisfaction [

18]. Children quickly realise in child–child play interactions that if their participation is too dominant or if they attempt to force their views on others, they are often left playing alone [

10]. Therefore, children’s participation and voice are closely associated with the process of empowerment as part of experiencing and building social relationships, being involved in play, having ideas affirmed or ignored, and building capacity to be adaptable and flexible in play situations [

19].

1.4. Ownership

Children want to feel that they are part of something, for example a family, an early childhood setting, or part of a wider community [

20]. When children have a sense of ownership they engage with and support other children through their actions and interest in what is happening around them [

21]. Having control or ownership of something helps children feel secure and confident in what they are doing. It is powerful because children feel comfortable and secure in the situation, have knowledge about what might happen and are familiar with the other children around them [

22]. Ownership supports active interest and engagement in contributing and influencing what is happening and taking a leading role in the development of play. Therefore, recognising children have a vested interest in their play environment supports the validity of their play agenda, allowing children to follow their own interests and come to their own conclusions [

19].

The term ownership is a deliberate choice because it is personal to the child’s individual experiences. In any given situation there are always external factors that have greater influence over what a child is able to do and the choices they can make; for example, boundaries are set by an adult, time is controlled by the daily routine, choice of what to do or who to play with is set by the resources available and the structure of classes. Within all of these rules and regulations, children can have the opportunity to ‘own’ for themselves something that is interesting or important to them.

When children are able to engage with materials in different and creative ways, they have the opportunity to express independent thought and be able to follow it through to a conclusion of their own satisfaction. It is an emotive response of being included and a tangible experience of sharing something that has happened, been created, or achieved together. Children’s actions and the way they develop play when it consists of their own ideas and experimentations supports a sense of owning the materials and space and what they can do with them. Through the ownership of play, common interests also emerge in the interactions between children; they begin to seek out each other to play with and often the same themes and games appear. When children cooperate, working towards the same goal or purpose, their play supports the sense that they are in control of the immediacy of their environment.

Ownership reaffirms familiarity in the processes of common practices which often reflect children’s particular community and culture [

20,

22]. When there is a sense of ownership in children’s play there may also be characteristics of group cohesiveness in working together, coming up with creative solutions to problems and children feeling able to express their personality and emotions [

16]. These connections are significant to the development of being empowered. Ownership relates closely to children’s knowledge and how they use that knowledge to support the development of their play and involve others [

23]. However, it does not have to be the physical ownership of an object but can also be ownership of an emotion or memory. Children might share a smile between them, remembering when they last played the same game, or express themselves through their physical movement, sharing the same feeling [

3].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framing

The framing for this research is based on social phenomenology, exploring the subjective experiences of early childhood practitioners observing children’s play through an empowerment lens. The often taken-for-granted aspects of children’s play are examined through a focus of layered experiences and interactions in social and child-led spaces. Through social phenomenology meaning is given and judgements are made in situations [

24]. The focus of this study is the way in which the EF is used as an analytical yet subjective meaning making tool. Social phenomenology involves two aspects of interpretive understanding: the process by which sense is made or interpreted through everyday happenings, in this research, observing children’s play; and the process by which generalisations are constructed [

25]. The empowerment framework is used to interpret children’s play from an empowerment perspective, but also to act as a critical facilitation for analysing approaches and professional judgements about play. The professional discussions between practitioners enable narratives around children’s lived experiences to be recognised as more than casual events. Therefore, the intersubjectivity that social phenomenology supports, creates discourse focused on the way in which play and the spaces that children occupy during play can support the process of empowerment.

2.2. Method

The study followed a qualitative ethnographic case study design consisting of two case studies, a group of childminders (3) from the South West of England and practitioners at a pre-school setting (2) located in the West Midlands. There was a total of 5 focus children: 3 children in the childminder group and 2 children in pre-school. These are referred to as nested cases (

Table 1). The research design consisted of an induction to the empowerment framework and how to use it facilitated by the researcher; data generated by the practitioners using the framework (observations and supporting evidence of children’s play); interviews and a focus group between the childminders and the pre-school at the end of the study. A timeline for the data generation methods which was replicated in both case studies is outlined in

Table 2.

The research explored the use of the EF as an analytical tool for observing children’s play and reflecting on the ways in which children are empowered in play and their environment. It specifically focused on the ways in which children participate and demonstrate ownership and voice when playing with peers; these are the three dominant themes of the EF. The childminders and practitioners generated all the data in the study. Consequently, the process outlined in

Table 2 was essential to the progress of the research in understanding the theory behind the EF, ethical implications, approaches to observations and supporting evidence such as photographs or video, and the level of detail required for recording and reflecting on children’s play through an empowerment lens. This paper reports on the first phase of a larger project and therefore it was essential that each stage of the data generation process was carefully considered.

The research question asked: In what ways are children empowered through their play environment? and What are the challenges of recording children’s empowerment for practitioners? A narrative methodology sought to understand and reflect on children’s ‘in the moment’ lived experiences [

26] of the ways and degrees to which they were empowered. Play experiences for the children in the 5 nested case studies was different yet had commonalities in terms of supporting a sense of freedom within the boundaries of play to express views and opinions and explore their environment in ways that interested them.

2.3. Participants

After a UK-wide interview based on the research of the Empowerment Framework, Early Childhood professionals were encouraged to contact the researcher if they were interested in trialling the EF in their practice. The participants in this study were some of the first to come forward, willing to engage with a paper-based version of the framework. It was important to keep the sample size small and manageable because it is initially time-consuming considering children’s play and environments through a different lens and it was important to understand how the EF could work as an observational tool as well as how it might influence practice. The childminders had been in practice for 10 years (Anya) and 15 years (Grace) with Bella joining Anya as an assistant childminder in the last year. All 3 hold a UK recognised level 3 qualification with Anya also holding a BA (Hons) in Early Childhood. Debbie and Mia from the pre-school have 30 years’ experience between them. Debbie has a degree in Early Childhood and Mia is in her final year of part-time study for her degree.

2.4. Ethics

Ethical considerations included processes that provided practitioners with the confidence and freedom to enable them to collect data and gain children’s and families’ consent. This was important, given the aim of gaining insights into children’s empowerment through their self-expression and lived experiences in play. Alongside adhering to the British Educational Research Association (BERA) guidelines [

27], parents consented for their child to be part of the research through signed consent managed by the practitioners, and they had the opportunity to withdraw from the research before a set date. The children, aged between 4 and 6 years old, were asked for their assent rather than full informed consent [

28] through explaining during circle time that practitioners would be thinking about their play in a different way. Children’s assent mitigates against not knowing whether children understand the context in which the research will be presented or the implications for them later. Children were able to withdraw from any play situation at any time and parents/carers and practitioners therefore acted as ‘gatekeepers’ for children’s wellbeing and gauged if they were happy to participate. In reality, children were not being asked to participate or do anything differently from their daily routine or play preferences. It was the way in which play was recorded and reflected upon that was different and this was the responsibility of the practitioners involved. Practitioners shared their observations, video, and photographs before or during interviews with the researcher towards the end of the study. All data were stored securely with names of participants changed to pseudonyms to protect their identity.

2.5. Observations

Children’s play was observed using the prompt questions of the EF and supported by video or photographs. Observations were recorded in a number of ways: at the time using brief handwritten notes; shortly after the play had concluded when the observation was clearly remembered; or at the end of the day, typed up when reflection could also be added to the observation. The way in which practitioners experimented with the timeframe of recording the observations was an important element of the research for future planning of the study as well as the actual content of the observations. The number of observations was also left to the practitioners’ professional judgement. The practitioners knew the children and were best placed to gauge the number of observations to support a layered picture of children’s empowerment to emerge. The focus was on the quality of observations, not the quantity; therefore, some practitioners did less detailed, in-depth observations whilst others did many shorter observations (see

Table 3). Knowledge created through this type of observational analysis constantly evolves and understanding situated within a context is not value-free or independent of interpretation [

29]. However, the fluidity and independence of how the observations were created supported richness in the detail that emerged. The insight provided through observational narrative data and the nature of recognising the importance of children’s shared experiences and how this relates to empowerment is a significant element of this research.

2.6. Interviews and Focus Group

After the observational data were generated, practitioners and childminders were invited to one-to-one interviews to share their insights and reflections. This was in person at the pre-school setting and online for the childminders. The interviews were based on semi-structured interview questions enabling direct comparison to be made between answers to questions. It was important that the interviews were done individually so that participants did not feel pressured to answer in a certain way or reveal anything that was sensitive to their practice. The interviews focused on the way in which participants experienced recording the observations and looking at play and the environment through an empowerment lens.

The focus group was an opportunity to bring all participants together online to share the perceived benefits and challenges of working with the empowerment framework. It moved away from the specifics of data content to the practicalities of using the EF. It was important for the research to know if the majority of participants shared opinions about the framework so that moving forward, changes could be implemented.

2.7. Data Analysis

Using key points from the literature review, theoretical framing, and re-reading of the data (observations and transcripts of interviews and focus group based on using the EF) key benefits and challenges were identified [

30]. These form the basis of reflection on how effective it was to identify children’s empowering experiences. Using an empowerment lens to observe children’s play in different environments provided an opportunity for participants to position themselves differently, thinking about children’s actions and relationships with other children in a new way. Thematic analysis of the benefits and challenges as a flexible method enabled focus on analysing meaning across the entire dataset of observations of children’s play experiences and practitioner reflections.

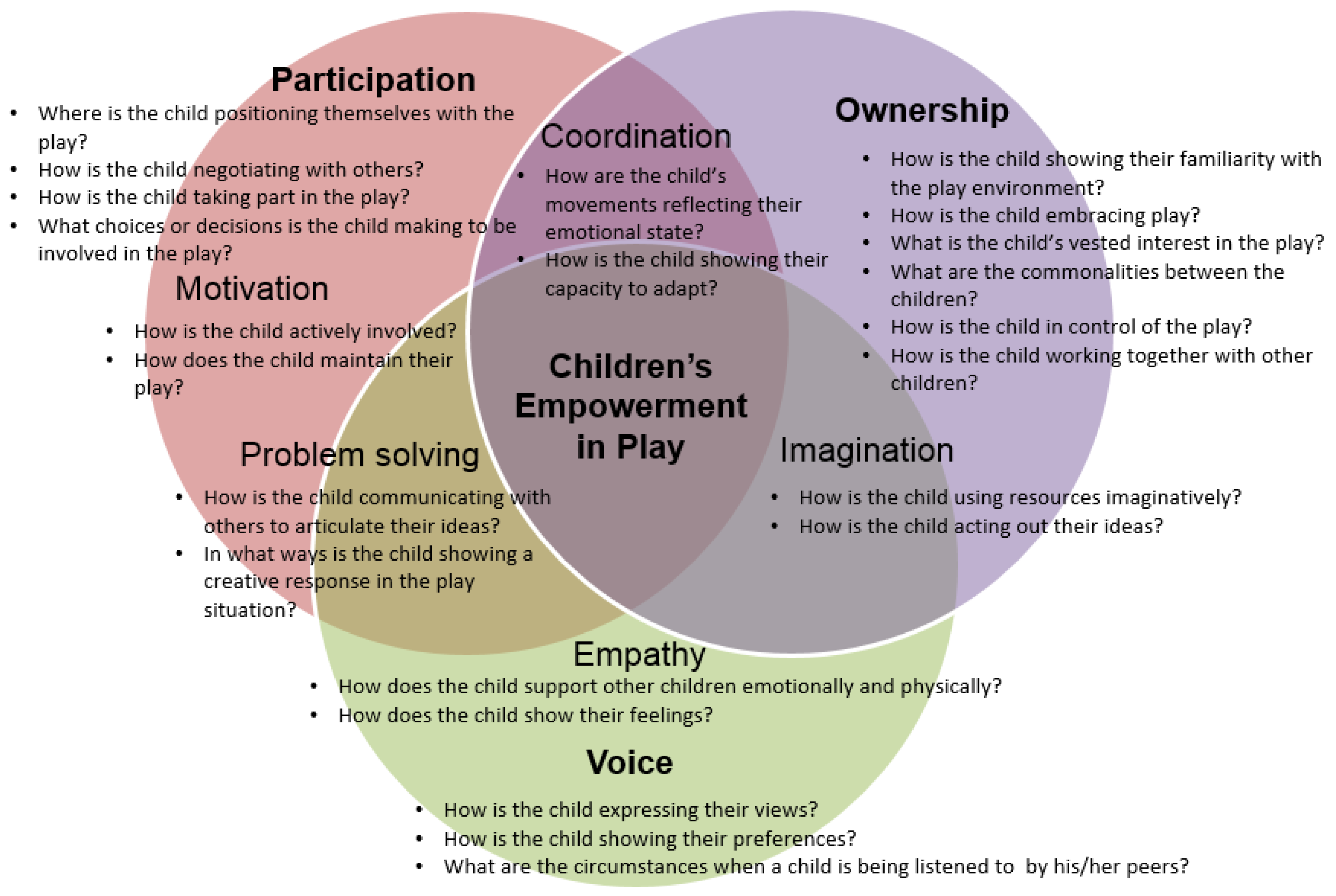

The observations of children’s play are based on using the empowerment framework, consisting of the 3 guiding themes, participation, voice, ownership, with open-ended prompt questions supporting the practitioner to record how children are playing. The prompt questions are detailed in

Figure 1. The prompt questions were converted into a table rather than a diagram so practitioners could record their observations more easily. However, the diagram indicates how the themes of the EF are layered and interlinked, therefore they are not distinct features but are influenced by each other. This is more difficult to represent in a table.

3. Results

The three extracts from the findings (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6) demonstrate the way practitioners are thinking about

how children are doing something through an empowerment lens rather than recording

what they did or achieved. This is the first time practitioners had used the EF for observation purposes and so it was not only about observing in a different way, but the experience of writing through an empowerment lens and the reflective practice this process ignited.

The EF enabled Anya and Bella to analyse and reflect on George and Albie’s play within the structure and boundaries of their environment. The boys had adapted their environment to meet their needs, creating a den inside, a covered, more intimate space within an existing space. This took time and therefore was an important element of their play and subsequent conversation. For Anya and Bella there were no additional demands to plan activities or provide resources. The EF simply required them to observe George and Albie’s play, interactions, and environment in a different way, through an empowerment lens. Identifying those empowering interactions through written descriptions meant that Anya and Bella could think in a more lateral way, for example, building on the children’s interests and preferences around den making, light and dark spaces, creating more intimate, smaller, and enclosed areas within the house to encourage child–child conversations. It was also evident to see Anya’s sensitivity to the content and privacy the children had created through her acknowledgement of the inappropriateness of collecting supporting evidence. The environment the children had created was their space; a space where they were comfortable talking to each other about issues that mattered to them. They learnt something about each other, and Anya and Bella were also made aware of the significance of the dark to the children. Without them having the opportunity to express their voice in the environment that they had imagined and created, this knowledge about the children would not have been revealed in the same way.

The EF encourages practitioners to notice the everyday play moments that are sometimes overlooked because they feel inconsequential. In a traditional observation attention may have been paid to the physical skills Josh was displaying rather the way he was commanding the play space. The shift of focus to the way in which Josh had ownership of the space not only revealed to Debbie how he could be decisive and confident but gave her potential ideas for furthering opportunities to build these skills in different contexts. The physicality of the space and Josh’s familiarity with it supported the way in which he used it to his advantage to follow his own agenda in what he wanted to get out of the experience. Debbie’s reflection ignited ideas on how she could support the same sense of ownership Josh displayed in different environments, perhaps by using similar resources or encouraging more physical movement in the indoor space.

Moving the attention away from the potential primary observation of the girls playing on the swings to the focus on Sacha trying to infiltrate the play gave Mia more opportunity to analyse the tactics Sacha was employing and recognising her knowledge and understanding of the group dynamics between the girls. The emotional risk that Sacha is not sure about taking is significant in this observation and links to the way in which she is cognitively processing the way in which she could participate in the game without suffering rejection. To examine and reflect on those moments is demanding. It required Mia not only to acknowledge there is meaning in the smallest detail but to try to capture that meaning through her analytical reflections about what she already knows about Mia and how that experience may contribute to her empowerment and future learning. In extract 4 (

Table 7) Bella and the researcher discuss the significance of how children choose to engage and what that means for Bella’s professional understanding of children’s processes of empowerment.

The recognition that the perception of ‘doing nothing’ is something that can be analysed and be a foundation for building future opportunities is significant. The environment is also a factor in how children engage with what is happening around them. Recognising this helped develop Bella’s observations and fed into the focus group discussion and reflection aspect of this research.

Focus Group

The focus group discussions where all the practitioners joined together online to discuss their experiences of using the EF were important to the initial phase of this research. They reflected on the process of engaging with the framework and some of the challenges they faced:

Using the framework for observations was interesting and certainly made me think deeper about what I was seeing the children do. The change of focus was initially quite challenging as I am used to writing about what a child has achieved and the next steps to encourage development (Anya, Childminder).

It also enabled practitioners to think about their practice in a different way. It was not about changing what they did, but how they approached observing what children were already doing as Grace reflected:

As a childminder, I think the empowerment framework could work well in my practice, because I am always following the children’s interests and working with them to provide experiences that are initiated by them. Focusing on participation, voice, or ownership fits into that quite well and I found myself reflecting more easily, you know it came more natural to me because the questions prompted me to think (Grace, Childminder).

The biggest challenge for practitioners was fitting in the observations around other daily responsibilities and feeling that they had ‘done enough’. This relates to the culture of expectation around outcomes, stretching and testing children and constantly monitoring progress [

31]. Children’s play is promoted within UK curriculum guidance as having a purpose, having a structure, and reaching a satisfactory conclusion [

32]. However, the nature of the current early years curriculum is compartmentalised into areas of learning, rather than adopting a holistic approach to children’s experiences and learning. The most up to date guidance pertaining to assessment arrangements states that paperwork should be kept to a minimum, but ‘practitioners need to illustrate, support and recall their knowledge of the child’s attainment’ [

33] (p. 11). For many practitioners this translates into generating a quantity of examples of children’s attainment, rather than fewer quality instances. Mia summaries this anxiety:

Time is the biggest barrier for me using the EF at the moment. It takes longer to do the observations, but I recognise they are more meaningful. Perhaps I would get used to doing less observations, but more detailed ones, but it makes me anxious to stand back and just observe, I feel I always need to be in there, doing something (Mia, Pre-school practitioner).

The results of the study demonstrate that using the EF is possible and can fit into the routines of early childhood settings. Practitioners do not require specialist knowledge to engage with the process, yet a reflective disposition is helpful making the most of the prompt questions under each of the themes. The balance between reflective practice and stimulating provision through the settings environment is an essential combination to support children’s learning and development through the EF.

4. Discussion

There are two research questions in this initial study: one focusing upon children’s empowerment through play and the environment; and the other examining the change required in everyday observations for practitioners to acknowledge the impact of empowerment for children’s learning and development. These two elements are interdependent on the way in which early childhood practice is regarded and the extent to which it is child-centred. The discussion centres on the themes resulting from the benefits and challenges of using the EF in practice.

4.1. Environment

Children find ways to engage with their environments, from playing with materials provided for them to making their own imaginative play in an empty space [

34]. From the extracts in the results section (

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7), all of the children were involved, although in very different contexts because their engagement came from what they were interested in and what they wanted to do or try to achieve within the space. Even when play does not work out in the way intended (Sasha not really entering the play with the girls on the swings), she is still practicing the skills and having the experience of taking a risk which will lead to further opportunities for her. The physical environment provides a foundation for empowering experiences, but the way in which the environment is structured for children to have the space and time to explore their own ideas, emotions and relationships is also significant.

The empowering moments are when the physical and emotional environment afford children the opportunities to engage in that space on their own terms. When the play environment provides a continuum of opportunities children incorporate the world around them, stimulating qualities such as curiosity, creativity, and inventiveness [

10]. The play environment can also evoke strong emotional responses depending on the situation and can be a positive and/or negative experience. Children explore a sense of who they are, especially as they develop relationships with their peers and explore social situations together through play [

23]. A play environment may not always be a comfortable space for children but through navigating the space they are able to experience moments of empowerment and the more the environment affords empowering experiences, the more empowered and confident a child will become in that space, for example Josh in extract 2 (

Table 5) demonstrates his skills through his familiarity and confidence with the environment. Consequently, it is not just the practitioners’ observational lens that requires a shift in thinking, but also the way in which children’s spaces and places are recognised as supporting empowering experiences.

The spaces children occupy when they play and how they incorporate them into their creative and imaginative worlds contributes to the meaning making and layered picture of learning and development play represents [

35]. The environment can determine the structure of play, offer possibilities, and provide a sense of freedom for children’s exploration and curiosity [

1]. Although often seen to facilitate children’s engagement; the environment is an essential element for supporting children’s verbal and non-verbal expression and sense of empowerment. This can be seen in extract 1 (

Table 4) where George and Albie talk about their feelings towards the dark. Children’s engagement with the environment they are familiar with is often based on routine. In some ways that provides children with a sense of security and confidence, but also leads to complicity in what children do within a space. The Empowerment Framework asks practitioners to think about how children use different spaces and what that experience affords them in terms of exploration, creativity and supporting curiosity. The spaces children occupy offer different experiences and if they are able to have some control over what they can do or the resources they use then this supports a process of empowerment. Thinking through an empowerment lens may lead to changes in how early childhood environments are presented or used. The extracts in the results section demonstrate the intertwined nature of the environment influencing children’s empowerment and what they think, feel, and do within certain spaces. The way in which the EF observations are now helping practitioners see the environment differently, supporting different purposes and how they can assist in children communicating or expressing their feelings through changing the environment is significant.

4.2. Subjectivity

The subjectivity of observations is something that all the practitioners found challenging. The fear of being wrong or interpreting what children were doing in the wrong way was a barrier to actually making observations. There are no ‘right or wrong’ answers in the EF; each observation supports a layered picture of practice to and understanding/knowing children is at the centre of this practice [

35]. The journey of professional practice and being supported in that process by other colleagues was significant for participants. They found the ability to talk to one another (childminders were part of the same network and in close geographical proximity and pre-school practitioners were at the same setting) gave them confidence as the fieldwork element of the study progressed. De Sousa identifies this as pedagogy in participation: learning from each other, sharing reflection, and gaining meaningful insight to practice [

36].

The framing of the research within social phenomenology challenged practitioners to have confidence in their subjective analysis of empowerment and children’s play. The layered and detailed observations from different play contexts and how the environment supported children’s empowering experiences was significant in contributing to understanding children’s engagement and interest. The EF is a subjective meaning-making tool to support practitioners in understanding and analysing the judgements they make about children’s experiences. Used as a tool for critical facilitation for analysing approaches to observation practitioners can have more meaningful professional discussions about children’s learning and development. It enables practitioners to have different views and come to different conclusions without fear of being criticised because it is what they have observed, guided by the prompt questions in the framework. The narratives around children’s lived experiences are rich platforms for shared understanding, not only between professionals, but for families. In time this can enable more empowering opportunities to develop and lead to changes in practice environments that focus on empowerment and empowering experiences.

4.3. Time

Engaging in reflection and support from others using the EF is time consuming because of the other daily demands. The EF advocates for slow pedagogy [

37] where less is more in terms of detailed and meaningful observations that centre on children’s capabilities rather than outcomes. The environment for children’s participation, ownership, and voice requires subtle changes so that practitioners are able to be more attuned to following children’s lead and having confidence that the environment will underpin the possibilities for learning and development.

Creating time for observing children and adopting an ethos of slow pedagogy is challenging. Supporting young children’s learning and development is demanding and often pressured. Practitioners work in an environment that requires them to be pro-active, always moving, doing, talking, or showing [

5]. Therefore, the idea of slowing down practice, stepping back and trusting in professional knowledge of child development is a transition that requires time and readjustment [

37]. As Mia reflected in the focus group, standing back can lead to anxiety if the foundation of professional understanding and the trust in own knowledge is not clear.

4.4. Learning

The pedagogic practice that practitioners adopt is central to children’s play experiences. Consequently, there are implications for learning and development, for example in extract 1 (

Table 4), Anya reflects on how overhearing the conversation between the two boys about being scared of the dark has made her think about Albie as a more reflective thinker. This will influence how she approaches other subjects in the future. In the UK, a consideration for parents in choosing an early childhood setting is whether they believe their child will fit in and be happy in the space with other children and practitioners [

38]. These elements are reflected in the pedagogic approach, strategies to engage children and the environment that is created. Practice based on the empowerment framework starts from what children can already achieve and emphasises how they use the people around them and their environment to explore and navigate those learning opportunities. The open-ended nature of the observation questions allow flexibility and rely on the value base and professional judgment of practitioners. The gradual build-up of observations around the three themes of participation, voice, and ownership, create a holistic picture of children’s abilities, interests, and relationships [

3]. Over time this can lead to a potential shift in the way practitioners think about learning and the most effective way to support them in this process. A good example of this is in the conversation in extract 4 (

Table 7) between Bella and the researcher, where Bella realises that even when children are not expressing traditional play behaviour, they are still engaged in important learning and development skills such as decision making.

4.5. Limitations of the Research

This is a very small-scale study involving five practitioners and five children over an eight-week period in two geographical locations in the UK. It reports on the initial roll out of the Empowerment Framework developed as part of PhD research in everyday early-years practice settings. The research has highlighted some valuable benefits and challenges to using the EF in everyday practice and some of the work that will be required if the EF is to be adopted more widely in the UK. A digital version of the EF is planned and will help in the logistics of recording observation as well as sharing with parents and families.

5. Conclusions

The empowerment framework enables practitioners to view children’s play and engagement with their environment through an empowering lens. It emphasises what children can do, taking a positive approach to their everyday interactions and recognising the learning, development and stimulus that is naturally evident when children can make choices and decisions. The EF changes the way in which children are observed which ultimately leads to new ways of working and re-evaluating practice. Recognising and nurturing children’s empowerment is essential for children to believe in themselves, have confidence to voice their opinions, try out new ideas and engage with the world and others around them. The EF highlights how those often subjective and abstract ideas be captured and stimulated through the environments children experience and the way in which practitioners value play.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of The Open University HREC/4112 14 October 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Canning, N.; Payler, J.; Horsley, K.; Gomez, C. An innovative methodology for capturing young children’s curiosity, imagination and voices using a free app: Our Story. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2017, 25, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, C.; Cheung, A. Towards holistic supporting of play-based learning implementation in Kindergartens: A mixed method study. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, N. Children’s Empowerment in Play; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud, J. The theory of empowerment: A critical analysis with the theory evaluation scale. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsek, A.; Perlman, M.; McMullen, E.; Falenchuk, O.; Fletcher, B.; Nocita, G.; Kamkar, N.; Shah, P.S. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the associations between professional development of early childhood educators and children’s outcomes. Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 53, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, H. Children and regeneration: Setting an agenda for community participation and integration. Child. Soc. 2003, 17, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R. Participation in Practice: Making it meaningful, effective and sustainable. Child. Soc. 2004, 18, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, B. Children’s right to participate: Challenges in every day interactions. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2009, 17, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsevreni, I.; Tigka, A.; Christidou, V. Exploring children’s participation in the framework of early childhood environmental education. Child. Geogr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Moss, P. Listening to Young Children: The Mosaic Approach, 2nd ed.; National Children’s Bureau and Joseph Rowntree Trust: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Fleer, M. Commonalities and Distinctions across Countries. In Play and Learning in Early Childhood Settings: International Perspectives; Pramling Samuelsson, I., Fleer, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- McCarry, M. Who benefits? A critical reflection of children and young people’s participation in sensitive research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2012, 15, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy-Smith, B. Councils, Consultations and Community: Rethinking the Spaces for Children and Young People’s Participation. Child. Geogr. 2010, 8, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shier, H. Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Child. Soc. 2001, 15, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treseder, P. Empowering Children and Young People: Training Manual; Save the Children: London, UK; Children’s Rights Office: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Flewitt, R.; Price, S.; Korkiakangas, T. Multimodality: Methodological explorations. Qual. Res. 2019, 19, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Johansson, E. Play and learning—Inseparable dimensions in preschool learning. Early Child Dev. Care 2006, 176, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbaud, S. The Essence of Play. In Playwork: Theory and Practice; Brown, F., Ed.; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2003; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- James, A.; Prout, A. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood. Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, S. Children’s voices: Young children as participants in research. In Young Children’s Creative Thinking; Fumoto, H., Robson, S., Greenfield, S., Hargreaves, D., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012; pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, P. Children’s participation in ethnographic research: Issues of power and representation. Child. Soc. 2004, 18, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, M. Working toward play: Complexity in children’s fantasy activities. Lang. Soc. 1995, 24, 315–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, A. On Phenomenology and Social Relations: Selected Writings; Wagner, H., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P.; Lukmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, S. Narrative Inquiry: Towards theoretical and methodological maturity. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017; pp. 546–560. [Google Scholar]

- British Educational Research Association [BERA]. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, 4th ed.; BERA: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018 (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Hill, M. Ethical considerations in researching children’s experiences. In Researching Children’s Experiences: Approaches and Methods; Greene, S., Hogan, D., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005; pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M.; Atkinson, P. Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE). Early Years Foundation Stage Assessment and Reporting Arrangements; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, M.; Lee, W. Learning Stories: Constructing Learning Identities in Early Education; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education (DfE). Early Years Foundation Stage Statutory Requirements; Crown Copyright: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, F. The fundamentals of playwork. In Foundations of Playwork; Brown, F., Taylor, C., Eds.; Open University Press and McGraw Hill: Maidenhead, UK, 2008; pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Eldén, S. Inviting the messy: Drawing methods and children’s voices. Childhood 2013, 20, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, J. The plural uses of pedagogical documentation in Pedagogy-in-Participation. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 30, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, K.; Clark, A. Potentialities of pedagogical documentation as an intertwined research process with children and teachers in slow pedagogies. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 30, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, L. An Investigation into the Factors that Influence Parental Choice of Early Years Education and Care; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).