Abstract

Educational and healthcare professionals need to develop emotional communication with schoolchildren and patients, respectively. This study aims to analyse the psychometric properties of an instrument that evaluates emotional communication among these professionals. A total of 406 professionals and students of education and health sciences took part in the study. They were administered a questionnaire using a Google Form that collected different elements of emotional communication. An exploratory factor analysis was carried out from which three factors were extracted: Communicative Proactivity, Openness and Authenticity, and Listening. These were supported by confirmatory factor analysis. The internal consistency of the scale is also adequate, ranging from 0.69 to 0.82. This instrument is valid, and, in a self-reported, straightforward and time-efficient manner, can assess the emotional communication of professionals and students of education and health sciences.

1. Introduction

Our humanity is essentially affected by the connections we have with other people, because we are, in a way, the sum of our connections. Indeed, the times of adversity we are currently experiencing remind us even more of the value of contact and affective relationships between people.

A fundamental tool for establishing the bonds that connect us to others is interpersonal communication. This communication involves an interactive, intentional, multidimensional process, which takes place in a specific relational context and has consequences for relationships [1,2]. In fact, it has been shown that bonding and communicating or relating to others can improve our health and learning, as noted by Hayes and Fryling [3].

The relationship between the emotional components of communication and different psychological variables, such as secure attachment, appropriate coping strategies or problem-solving, has been demonstrated [4]. Differences in the emotional components of communication and attachment styles have also been established. Specifically, those with fearful styles tend to avoid intimacy with others, or those with a concerned style tend to express themselves verbally, probably due to the anxiety they manifest [5]. Therefore, it seems that the emotional components of communication are related to psychological stability.

Even in the proto-conversations that infants have with adults, affection is shared, based on the exchange of glances, smiles, and vocalisation [6]; just as voice modulation or prosody is fundamental when emotions are transmitted or received in preverbal humans [7]. The latter author points out that, as hypothesised by Darwin, the ability to express emotions through voice modulation was a key step in the evolution of spoken language. This type of emotional communication, initiated with infants, continues in families with older children when they engage in everyday activities such as family meals. Dialogues in these interactions are significantly associated with greater positive affection and commitment to the family and less negative affection and stress [8].

Emotional communication is also fundamental in educational and health contexts, as it has an impact on the quality of teaching–learning processes, on doctor–patient relationships [9,10], and on the therapeutic bonds between psychology professionals and clients [11,12,13].

In educational contexts, the importance of teachers’ emotional communication when addressing schoolchildren is evident. In fact, when teachers engage in insincere and inauthentic non-verbal communication, when they are opaque in conveying information and show little communicative competence, students will tend to invest a great deal of effort in controlling themselves emotionally when conversing with such teachers. This effort is related to uncomfortable and intense emotions in students, such as anger, anxiety or embarrassment. By contrast, when students perceive their teachers as sincere and using authentic non-verbal communication, clarity in conveying information and communicative competence, they perceive teachers as emotionally supportive, which prevents these uncomfortable emotions [14].

Different authors point out that emotion and communication go hand in hand, so there is a relationship between the use of communication skills and the emotional intelligence of future teachers [15]. An effect, albeit indirect, has also been found in the communication that school principals have with their teachers when they support them emotionally. This emotional support is based on empathic listening, the use of explicit empowering messages, and the normalisation of moderately problematic situations [16].

Specifically, regarding teachers in initial training, the study by Aparicio Herguedas et al. [17] on non-verbal communication with university physical education students found that these future teachers had difficulties in their kinesic communication and in managing their paralinguistic resources and interpersonal space. Thus, the authors concluded that such limitations in interacting non-verbally in a teaching-learning situation could lead to unpleasant emotional experiences due to inadequate use of communicability as teachers. It also highlights how future teachers are often unaware of the importance of non-verbal language in communicative acts.

In general, studies seem to confirm that trainee or novice teachers lack strategies and skills to communicate with students [18,19]. In the study by Camnus Ferri et al. [18], trainee teachers acknowledge that they do not feel prepared to provide efficient and effective communication in the classroom and tend to use verbal communication strategies, leaving aside non-verbal and paraverbal communication, which are necessary to maintain students’ attention. Following these authors, it seems teaching communicative competence is a field that has been little researched and requires further investigation.

In the health field, the emotional communication of medical and nursing professionals with patients has been extensively studied in different pathologies from diabetes to cancer. In this regard, several studies conclude that when a health professional has high-quality communication skills, it improves patient satisfaction, patient engagement with the professional’s treatment recommendations, and clinical outcomes in various aspects of health, as noted in a meta-analysis by Zolnierek and Dimatteo [20].

Another study by Park et al. [21] found that clinicians treating patients with HIV focused on them more when patients made their emotions explicit, repeated them several times, and when related them to medical issues, such as the symptoms they experienced.

This type of communication has also been analysed with adult cancer patients, concluding that most of them prefer medical professionals to respond to their emotions of distress with sensitivity, acknowledgement, and support [22]. Conversations held by medical professionals with families of children with cancer have also been analysed. In such studies, it was observed that families’ emotional expression takes the form of subtle, non-explicit signals. Doctors often respond to these signals by offering information about the pathology but do not delve into the emotional aspects of the families, which hinders true emotional and empathic communication [23].

Different studies also point to the importance of the therapeutic alliance in the practice of clinical psychology, so that this, regardless of the therapeutic orientation, influences improvements in clients [11,12]. This alliance is characterised, according to clients, by empathy or unconditional warmth and acceptance on the part of the psychology professional [11]. In fact, Norcross and Lambert [13] consider, based on their meta-analysis, that: (a) alliance, both in individual child and adolescent psychotherapy as well as couple and family therapy, (b) collaboration, (c) consensual goals, (d) cohesion in group therapy, (e) empathy, (f) consideration and positive affirmation, which consists of valuing and supporting clients at all times, and (g) collecting and giving feedback to the client are demonstrably effective factors in therapy. Thus, some training programmes in these emotional and affective skills have been carried out for psychology professionals and have demonstrated their effectiveness [24].

Although communication skills are a central component of clinical practice [25,26], they do not seem to have the same importance in the academic training of medical students [27,28]. Some studies link this formative gap to negative attitudes of teachers, academic leaders and students as an innate and subjective (non-scientific) skill, which would take time away from other necessary knowledge [29,30]. Specifically, medical students’ negative attitudes are due to their lack of understanding of why these skills are useful, biomedical epistemological interpretations, as well as how they could be included and taught in the curriculum [30].

Several authors also point out that factors of interpersonal communication can be considered part of emotional communication. These components refer to the expression of one’s own emotions, active or empathic listening, non-verbal communication, empathy, authenticity, warmth, and willingness to listen and communicate [6,20,21,23,24,31,32,33,34,35].

Moreover, there is a strong relationship between non-verbal communication and emotions. Facial-emotional expressions, as well as emotional behaviour, are considered deeply rooted patterns [6], establishing an important relationship between the sensorimotor system and the expression of emotions and feelings [36].

We know that non-verbal communication is important in the reception of messages transmitted through the body and voice. Specifically, linguistic expressions are complemented by changes in prosody and facial and body muscle configuration, and even the recipients of these messages have specific physiological responses measured through pupil dilation and skin colouration [37]. In fact, university students perceive being closer to teachers who are more expansive in their non-verbal communication. In this regard, there was a project whose objective was to train university teachers in body awareness and non-verbal communication to help achieve this closeness with their students [35].

Active or empathic listening is also a key skill in emotional communication, which some authors present as a communicative competence. It is defined as a way of listening and responding to others that enhances mutual understanding [33]. It includes both attitudes and skills, where attitudes are understood as empathy or unconditional positive acceptance, whereas maintaining eye contact, not interrupting, making encouraging comments and gestures, asking open questions, paraphrasing, reflecting, reframing, and summarising are listening techniques or skills. These all help achieve the fullest possible understanding of the message being conveyed [38,39,40]. This combination of empathy and skills can confer greater quality to the listening process between interlocutors [41], as the use of techniques alone without these attitudes is likely to result in mere automatisms.

According to some studies, teachers who lack communicative competence generally perceive themselves as poor “listeners” and often find it difficult or are even unwilling to express relational and meaningful messages to students [14]. McKay, Davis, and Fanning, [42] affirm that listening is one of the most important skills for quality interpersonal communication and describe different cognitive blocks that disrupt the listening process. They point out the importance of working on these skills in order for true interpersonal listening to occur.

Other authors have identified several socio-demographic and professional variables that influence teachers’ active and empathic listening. The results, without going into detail, indicate that women who have higher academic degrees (master’s or doctorate) have received training in mental health promotion and have support from their colleagues when they need it show greater active and empathic listening. Primary school teachers are also generally more likely to have empathetic listening than secondary school teachers [43].

Another emotional component of communication is authenticity, which has been studied in the field of health. Several authors note that this concept is ambiguous in research; however, most definitions state that authenticity in communication, specifically doctor-patient communication, involves “...the quality or condition of the information, or that the people (communicating) are relevant, real or genuine...” [34] (p. 111). Of the four dimensions, these authors consider regarding professional authenticity in health or education, there is one that refers to communication, which they call authentic relationship. This refers to creating a sense of genuine caring, leading to an equitable dialogue between professionals and patients. One of the conclusions of their research is that families who perceive their relationship with health professionals to be more authentic are better able to carry out the intervention plan assigned to them.

Closeness is another aspect that authors have considered in interpersonal and emotional communication. This communicative factor in relationships involves the exchange of emotions, thoughts and feelings. As Hayes and Fryling [3] (p. 137) affirm “if closeness depends on another person understanding how you feel and what you think, then closeness depends on people sharing their feelings”. This infers a genuinely emotional aspect to interpersonal communication.

How have the components of emotional communication outlined so far been measured? One method of assessing emotional communication has been through the analysis of conversational recordings, both in audio and video. One example is the Verona Coding Definitions of Emotional Sequences (VR-CoDES), which analyses explicit emotional expressions and more subtle emotional cues [44]. Another example was one conducted by Rhee, Park, and Bae [45], developing ad hoc categories to analyse affective interactions in work teams. Guaita [46] also constructed an observation protocol on the emotional aspects of communication from which he extracted three styles of emotional communication: the expressive style, in which expressive components predominate; the normative style with mainly emotional control components; the assertive style, in which emotion regulation components predominate.

Another way of evaluating emotional or emotion-focused communication is by means of inventories, from a self-evaluative point of view. Guaita [6] generated an inventory aimed at adults with two scales: one regarding work or non-close relationships and the other regarding family or close relationships. This author points out three categories used for its construction: expression of emotions, their regulation, and control of emotional expression. Other self-reported scales gather specific aspects of communication, such as active listening (AELS) by Bodie [47] or active empathic listening (ALAS) by Mishima et al. [48], which were translated and validated with Greek teachers by Kourmousi et al. [49,50]. The first scale consists of three subscales: (a) listening attitude, referring to unconditional positive regard for the other person; (b) listening skill, which includes aspects of listening techniques related to empathy; (c) conversational opportunity, which refers to the availability and accessibility manifested by the listener towards others. The second scale (ALAS) also consists of three subscales: (a) understanding (intuiting, grasping), which refers to the listener’s ability to perceive both the explicit and tacit expressions of others when they speak to him/her, (b) processing, which includes the ability to synthesise and remember the information they say, and (c) attention, which refers to the verbal and non-verbal means that help clarify the conversation and indicate attention for the other person.

In our case, we have opted for self-reporting to assess emotional communication, in order to collect the perceptions of different professionals and students. Thus, the aim of this study is to establish the psychometric properties of an emotional communication questionnaire aimed at education and health professionals and students of teaching and health sciences.

2. Materials and Methods

The participants were primary education teachers, health sciences professionals, students of two teacher training degrees (primary and infant education), and health sciences students, distributed as shown in Table 1. The total sample was made up of 406 participants, in which there was a greater presence of women than men (67% versus 33%) and of young people (71.2% between 19 and 41 years of age versus 28.8% between 42 and 63 years of age). With respect to their studies, there was less representation from the health sciences (7.6% practising professionals and 7.9% of students) than from teacher training (35.7% teachers and 48.8% students). All participants were residents of the Canary Islands (although the islands of Lanzarote and La Gomera did not participate).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

The instrument used is the Emotional Communication (EC) Questionnaire aimed at both practising professionals and future professionals. For its construction, a previous interpersonal communication questionnaire, the HABICOM Questionnaire by Hernández-Jorge and de la Rosa [51], was used as a starting point. Sentences relating to affective-emotional communication were extracted, which include dimensions of listening, inquiry, non-verbal communication, openness, warmth, empathy, authenticity, and predisposition to listen and communicate [35,52,53,54,55,56].

A total of twenty-one sentences were defined and placed in four theoretical categories: Openness, Non-Verbal Communication, Affective Exchange (with five sentences each), and Listening (with six sentences). It was completed by a sample of practising teachers and an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to the data to extract its structure and the analysis of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to analyse the internal consistency of the factors. From this first analysis, seven sentences were eliminated because the scores were dispersed in the different components and because their elimination increased reliability. Thus, a 14-sentence questionnaire was obtained, in which the sentence and a brief description of it are presented, with the aim of making it understandable. The response format is a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5 (1 = never, 5 = always), asking about the use of the skill indicated in the sentence.

The questionnaires were distributed, by means of a Google Form, to professionals who voluntarily wished to participate, always guaranteeing anonymity and data privacy. In the case of practising teachers, they were part of a broader project on the monitoring of the implementation of Emotional Education and Creativity (EMOCREA: subject of free assignation in the Autonomous Region of the Canary Islands). The students of teacher training were attending a course in the teaching degree in primary education and in early childhood education on emotional and socio-affective aspects. As we have pointed out, in both cases (practising teachers and teachers in training) the questionnaires were completed voluntarily. Health science professionals and students also participated voluntarily and at their convenience, and it was also the subject of final degree projects developed in the speech therapy degree. All these degrees are taught at the University of La Laguna. The data obtained from the same were included in an Excel template for subsequent inclusion in the database of the statistical program Spss v21 (IBM, Newyork, NY, USA, 2025) and in the Software R and ULLRToolbox for conducting the corresponding data analysis.

3. Results

The results are presented according to the analyses carried out. Firstly, the analysis of the structure of the questionnaire and its internal consistency is described, followed by the confirmatory analysis and, finally, the questionnaire’s scale.

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Internal Consistency

We have used principal components analysis (PCA) in an exploratory factor analysis. Regarding the structure of the questionnaire, a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index (KMO) of 0.829 (p ≤ 0.000) was obtained. Initially, four components were obtained, but some of them were composed of two items which, in turn, gave rise to another component, so it was decided to force the analysis to three factors, thus resulting in a clear allocation of each set of items. Table 2 shows the variance explained before and after applying the Varimax rotation, in which the factor structure explains 64.08% of the variance.

Table 2.

Total explained variance.

Table 3 shows factor loadings. For the first component, the values range between 0.586 and 0.744; while for the second component they are between 0.598 and 0.779. Finally, the items of the third component are between 0.619 and 0.830.

Table 3.

Factor loading matrix.

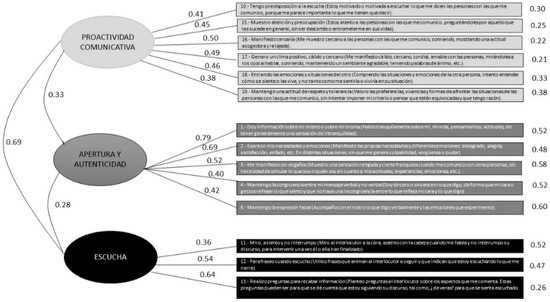

Component 1 is Communicative Proactivity and is made up of six items that are connected to maintaining closeness with other people, understanding their emotions and situations, generating a warm atmosphere in the interpersonal relationship, maintaining an attitude of respect and tolerance, showing attention and concern for the person with whom one is communicating, and having a predisposition to listen actively. Component 2 is Openness and Authenticity and is made up of five items that refer to offering personal information, expressing one’s needs and emotions, expressing oneself openly without deception, being expressive with one’s face, and maintaining congruence between verbal and non-verbal language. Finally, Component 3 is Listening, which encompasses three items related to the use of active listening strategies, such as paraphrasing, asking the other person about their situation, and external listening skills such as looking, nodding and not interrupting.

To study the internal consistency of the components, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated for each of them, showing that the questionnaire has high internal consistency in each of the components, with two of the factors being above 0.70; in those that are not increased by the elimination of any item (see Table 4). On the other hand, the Listening component has a lower alpha (0.658), increasing slightly to 0.675 if one of the components is eliminated.

Table 4.

Internal consistency of the components.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted with the total sample of participants in which the three-component model obtained in the previous PFA was tested and the relationship between the factors considered. Goodness-of-fit values of 0.090 and 0.085 (respectively) were initially obtained. Finally, the RMSEA value was 0.084 (90% CI: 0.072, 0.096). In addition to these, the following indices were also used: TLI (0.83), GFI (0.90), and χ2(74) = 240.16, p < 0.000. These indices allow us to conclude that there is an adequate fit of the model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factor loadings from items of the model with their confirmatory measures.

3.3. Scale

Finally, we wanted to analyse the scales of the questionnaire in order to establish differences in the variables extracted for those populations that required it. The scores were carried out according to the percentiles obtained from the participants in the study. The scores obtained are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Emotional communication questionnaire scale.

4. Discussion

In this respect, we can state that the questionnaire has adequate psychometric properties, as its factorial structure has been confirmed. This structure coincides with the variables considered in the scientific literature on emotional communication. These variables are: Communicative Proactivity, characterised by a positive attitude towards initiating and maintaining communication; Openness and Authenticity, understood as showing oneself to others spontaneously and without deception; Listening, as pointed out by different authors, to ensure affective and emotional communication [6,20,21,23,31,32,33,34,35].

Although there is no factor specifically referring to non-verbal communication [36], we understand that this dimension of emotional communication is transversally present in the variables that our questionnaire has isolated, through contents in items such as:

“... looking them in the eyes when I speak”.“I accompany with my face what I say verbally and the emotions I experience”.“I look the interlocutor in the face, nod my head when he/she speaks to me...”.

It is also important to note that the factor that most explains the content of emotional communication has a highly attitudinal component (Communicative Proactivity), emphasising the importance of a predisposition to establish affective exchanges with others. This variable is related to closeness [3], although in our case, as its name suggests, it emphasises its proactive nature, highlighting aspects that introduce a qualitative improvement in the interpersonal bond, such as generating an affective atmosphere, concern for others’ feelings or the tendency to listen, respect, and understand people’s emotional experiences. This would be more related to a competence factor in affective communication.

Regarding the authenticity factor, it should be noted that something similar to the above occurs. Although there is a similarity with the literature for this variable [34], in terms of generating a genuine and sincere relationship of affection that enables equitable communication, in our case, it is extended with competence elements such as expressiveness and congruence between what is said and what is done.

As for the last factor, emotional listening, it should be noted that the literature [38,39,40,41] indicates that this variable has a double component: one more conative-attitudinal (empathy) and the other more cognitive-behavioural (knowing how to listen). In our case, we have focused the assessment on the latter, more strategic aspect, locating a series of active listening skills that would make listening not only affective but also effective.

The internal consistency of each of the isolated components is adequate. This is particularly true for the first two components: Communicative Proactivity and Openness and Authenticity. The Listening factor is less consistent, although we do not consider it to be negligible. Perhaps these results arise because we have forced the factor analysis to three components since at the beginning it involved a fourth factor with only two items. In the first exploratory analysis, item 11 correlated closely with two of the factors. Instead of eliminating it, we opted to shape the theoretical structure and by forcing the factors, this item was clearly placed in aspects related to listening.

This reduction in the internal consistency of the emotional listening factor could also be related to the number and quality of the items of the listening factor, since, as we have indicated above, only the strategic component has been isolated, focusing on the skills to make active listening effective. Thus, attitudinal aspects associated with empathy have not been included.

In the confirmatory analysis, there are two items that are not as strong as the rest of the corresponding factors, but we consider that they show acceptable probabilistic values from the psychometric point of view and complement the construct. Thus, one of the items is related to the more external aspects of listening, while the rest of them relate to the internal or active listening aspects (paraphrasing or questioning) and have greater values. With the data, we consider that these three factors can define emotional communication, focusing on the most conative and strategic aspects such as the attitude of wanting to communicate (communicative proactivity), being an open and authentic person and listening emotionally.

Regarding limitations, this study would benefit from a wider and more diverse population, as the present work is composed exclusively of professionals and students of teaching and health sciences. The inclusion of other professionals from social work, psychology or speech therapy, among others, would undoubtedly enrich the sample. We are referring to professionals who need to establish communication with their patients, clients or users so as to strengthen the connection needed to achieve the objectives of their professions. It would also be interesting to apply other validity criteria to analyse the robustness of the questionnaire in greater depth.

We consider that this study provides an assessment instrument that captures in a simple, reliable and proven way the emotional communication of students and professionals in education and health sciences. Another benefit that we observe in the instrument in this study is that it can be answered easily, taking only a few minutes, which can help the person completing it to focus on the task, as it does not have an excessive number of items.

We are committed to working towards valid instruments for self-reporting different aspects of a psychological nature in a straightforward and time-efficient manner, with the aim not only of diagnosis but also intervention, since the factors we have isolated in this tool have a high competence component. Thus, the instrument could help when designing and evaluating training processes aimed at assisting professionals in the field of emotional communication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.R.-H. and C.M.H.-J.; methodology, F.R. and C.M.H.-J.; formal analysis, F.R. and C.M.H.-J.; investigation, A.F.R.-H., C.M.H.-J., F.R., O.K. and R.D.-M.; Resources, A.F.R.-H., C.M.H.-J., O.K. and R.D.-M.; data curation, F.R. and C.M.H.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.R.-H. and C.M.H.-J.; writing—review and editing, A.F.R.-H. and C.M.H.-J.; visualization, A.F.R.-H., C.M.H.-J., F.R., O.K. and R.D.-M.; supervision, A.F.R.-H. and C.M.H.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the participants deciding to get involved voluntarily.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to because the participants decided to participate voluntarily.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be located at the following address https://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/26934.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koprowska, J. Communication and Interpersonal Skills in Social Work, 2nd ed.; Learning Matters: Exeter, UK, 2008; p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- De Vito, J.A. Human Communication; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, L.J.; Fryling, M.J. Functional and descriptive contextualism. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2019, 14, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, L. Habilidades de Comunicación, Estilos de Apego, Estrategias de Afrontamiento y Solución de Problemas: Relación y Valor Discriminante en la Edad y el Género. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, La Laguna, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, L. Diferencia del Uso de Habilidades Comunicativas en Función de los Estilos de Apego en Personas Adultas. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, La Laguna, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guaita, V.L. Evaluación de los aspectos emocionales de la comunicación en adultos: Un análisis preliminar. LIBERABIT. Rev. Peru. Psicol. 2012, 18, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Filippi, P. Emotional Voice Intonation: A Communication Code at the Origins of Speech Processing and Word-Meaning Associations? J. Nonverbal Behav. 2020, 44, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shira, O. Assessing the relationship between family mealtime communication and adolescent emotional well-being using the experience sampling method. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirino, R.; Hernández, E. Comunicación afectiva y manejo de las emociones en la formación de profesionales de la salud. Educ. Méd. Super. 2015, 29, 872–879. [Google Scholar]

- Zabalza, M.A.; Zabalza, M.A. Profesores y profesión docente. Entre el “ser” y el “estar”. Rev. Docencia Univ. 2013, 11, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lavik, K.O.; Frøysa, H.; Brattebø, K.F.; McLeod, J.; Moltu, C. The first sessions of psychotherapy: A qualitative meta-analysis of alliance formation processes. J. Psychother. Integr. 2018, 28, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flückiger, C.; Del Re, A.C.; Wampold, B.E.; Horvath, A.O. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcross, J.C.; Lambert, M.J. Psychotherapy relationships that work III. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazer, J.P.; McKenna-Buchanan, T.P.; Quinian, M.M.; Titsworth, S. The Dark Side of Emotion in the Classroom: Emotional Processes as Mediators of Teacher Communication Behaviors and Student Negative Emotions. Commun. Educ. 2014, 63, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaral, T.C.; Hasan Ustu, H. Examination of the Relationship Between Teacher Candidates’ Emotional Intelligence and Communication Skills. J. Educ. Learn. 2019, 8, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I.; Eyal, O. Principals’ emotional support and teachers’ emotional reframing: The mediating role of principals’ supportive communication strategies. Psychol. Sch. 2018, 55, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio Herguedas, J.L.; Fraile Aranda, A.; Romero Martín, M.R.; Asún Dieste, S. La comunicación no verbal en la formación del profesorado de educación física: Dificultades y limitaciones experimentadas. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profesorado. Contin. Antig. Rev. Esc. Norm. 2020, 34, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus Ferri, M.; Iglesias Martínez, M.J.; Lozano Cabezas, I. Un estudio cualitativo sobre la competencia didáctica comunicativa de los docentes en formación. Enseñanza Teach. Rev. Interuniv. Didáctica 2019, 37, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, J.L.; Rodríguez, A. Competencias comunicativas de maestros en formación de Educación Especial. Educ. Educ. 2015, 18, 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zolnierek, K.B.; Dimatteo, M.R. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med Care. Augost 2009, 47, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Saha, S.; Han, D.; De Maesschalck, S.; Moore, R.; Korthuis, T.; Roter, D.; Knowlton, A.; Woodson, T.; Beach, M.C. Emotional communication in HIV care: An observational study of patients’ expressed emotions and clinician response. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 2816–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, L.N.C.; Schepers, S.; Tollenaar, M.S.; de Haes, H.; Smets, E. Patients’ and oncologists’ views on how Oncologists may best address patients’ emotions during consultations: An interview study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.A.; Friedrich, A.B.; DuBois, J.; Mack, J.W. Emotional Communication in Advanced Pediatric Cancer Conversations. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muran, J.C.; Safran, J.D.; Eubanks, C.F.; Gorman, B.S. The effect of alliance-focused training on a cognitive-behavioral therapy for personality disorders. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.M.; Hundert, E.M. Defining and Assessing Professional Competence. JAMA 2002, 28, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.M.; Kraft-Todd, G.; Schapira, L.; Kossowsky, J.; Riess, H. The Influence of the Patient-Clinician Relationship on Healthcare Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gude, T.; Tyssen, R.; Anvik, T.; Grimstad, H.; Holen, A.; Baerheim, A.; Vaglum, P.; Løvseth, L. Have medical students’ attitudes towards clinical communication skills changed over a 12- year period? A comparative long-term study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Givron, H.; Desseilles, M. The role of emotional competencies in predicting medical students’ attitudes towards communication skills training. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2505–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junod Perron, N.; Sommer, J.; Louis-Simonet, M.; Nendaz, M. Teaching communication skills: Beyond wishful thinking. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2015, 145, w14064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moral, R.R.; de Leonardo, C.G.; Pérez, A.C.; Martínez, F.C.; Martín, D.M. Barriers to teaching communication skills in Spanish medical schools: A qualitative study with academic leaders. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglander, J.; Sundler, A.J.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Holmström, I.K.; Eide, H.; Van Dulmen, S.; Eklund, J.H. Emotional communication with older people: A cross-sectional study of home care. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariste, E. Escucha Activa: Aprender a Escuchar y Responder con Eficacia y Empatía; Díaz de Santos: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mineyama, S.; Akizumi, T.; Soshi, T.; Kyoko, N.; Norito, K. Supervisors’ attitudes and skills for active listening with regard to working conditions and psychological stress reactions among subordinate workers. J. Occup. Health 2007, 49, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeeg, D.; Mortil, A.M.A.; Hansen, M.L.; Teilmann, G.K.; Grabowski, D. Families’ Adherence to a Family-Based Childhood Obesity Intervention: A Qualitative Study on Perceptions of Communicative Authenticity. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.M.; Caja, M.M.; Gracia, P.; Velasco, P.J.; Terrón, M.J. Inteligencia Emocional y Comunicación: La conciencia corporal como recurso. Rev. Docencia Univ. 2013, 11, 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, J.H.G.; Huggin, C.F.; Zupan, B.; Willi, M.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Sato, W.; Palermo, R.; Ortner, C.; Kripp, M.; Kreti, M.; et al. A sensorimotor control framework for understanding emotional communication and regulation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 112, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezecache, G.; Mercier, H.; Scott-Phillips, T.C. An evolutionary approach to emotional communication. J. Pragmat. 2013, 59, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, K. Active listening: More than just paying attention. Aust. Fam. Physician 2005, 34, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton, D.; Hamlin, D.; McCarthy, J.; Head-Reeves, D.; Schreiner, M. Learning to listen: Teaching an active listening strategy to preservice education professionals. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2008, 27, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger, H., Jr.; Castle, G.R.; Emmett, M.C. Active listening in peer interviews: The influence of message paraphrasing on perceptions of listening skill. Int. J. Listening 2010, 24, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drollinger, T.; Comer, L.B.; Warrington, P.T. Development and validation of the active empathetic listening scale. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M.; Davis, M.; Fanning, P. Los Secretos de la Comunicación Personal, 1st ed.; Espasa libros S.L.U.: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kourmousi, N.; Kounenou, K.; Yotsidi, V.; Xythali, V.; Merakou, K.; Barbouni, A.; Koutras, V. Personal and job factors associated with teachers’ active listening and active empathic listening. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Piccolo, L.; Finset, A.; Mellblom, A.V.; Figueiredo-Braga, M.; Korsvold, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zimmermann, C.; Humphris, G. Verona Coding Definitions of Emotional Sequences (VR-CoDES): Conceptual framework and future directions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 2303–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.Y.; Park, H.; Bae, J. Network Structure of Afective Communication and Shared Emotion in Teams. Behaioural Sci. 2020, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaita, V. Evaluación de los Aspectos Emocionales de la Comunicación en Niños en Riesgo por Pobreza Extrema: Una Mirada Neuropsicológica. Avances en Investigación en Ciencias del Comportamiento, 1st ed.; Richaud, M., Ison, M., Eds.; Editorial de la Universidad del Aconcagua: Santiago, Chile, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 289–318. [Google Scholar]

- Bodie, G.D. The Active-Empathic Listening Scale (AELS): Conceptualization and evidence of validity within the interpersonal domain. Commun. Q. 2011, 59, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, N.; Kubota, S.; Nagata, S. The development of a questionnaire to assess the attitude of active listening. J. Occup. Health 2000, 42, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmousi, N.; Amanaki, E.; Tzavara, C.; Koutras, V. Active Listening Attitude Scale (ALAS): Reliability and Validity in a Nationwide Sample of Greek Educators. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmousi, N.; Kounenou, K.; Tsitsas, G.; Yotsidi, V.; Merakou, K.; Barbouni, A.; Koutras, V. Active Empathic Listening Scale (AELS): Reliability and Validity in a Nationwide Sample of Greek Educators. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Jorge, C.M.; De la Rosa, C.M. Habilidades comunicativas en estudiantes de carreras de apoyo frente a estudiantes de otras carreras. Apunt. Psicol. 2018, 35, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinke, C.L. Principios Comunes en Psicoterapia; Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 1995; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz, M.A. Habilidades terapéuticas. In En Manual de Terapia de Conducta; Vallejo, M.A., Ed.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 83–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, W.H.; Cormier, L.S. Estrategias de Entrevista para Terapeutas, 3rd ed.; Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 2000; pp. 140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, D.; Hargie, O.; Morrow, N. Communication Skills Training for Health Professional; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1997; pp. 49–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, A. Curso de Comunicación: Cuaderno de Notas; Radio ECCA: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 1997; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).