The CPD Needs of Irish-Medium Primary and Post-Primary Teachers in Special Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Irish Immersion Education

1.2. Special Education in Irish Immersion Schools

1.3. Bilingualism/Immersion Education and Students with SEN

1.4. CPD in Immersion Education Contexts

1.5. CPD for Teachers in Schools in the Republic of Ireland (RoI)

2. Materials and Methods

- −

- What types of CPD do teachers in primary and post-primary IM schools undertake in special education?

- −

- What are the CPD needs of teachers in these schools in special education?

- −

- What are the motivating factors for teachers in IM schools when undertaking CPD in special education?

- −

- What are the challenges that IM teachers experience when accessing CPD in special education?

2.1. Data Analysis

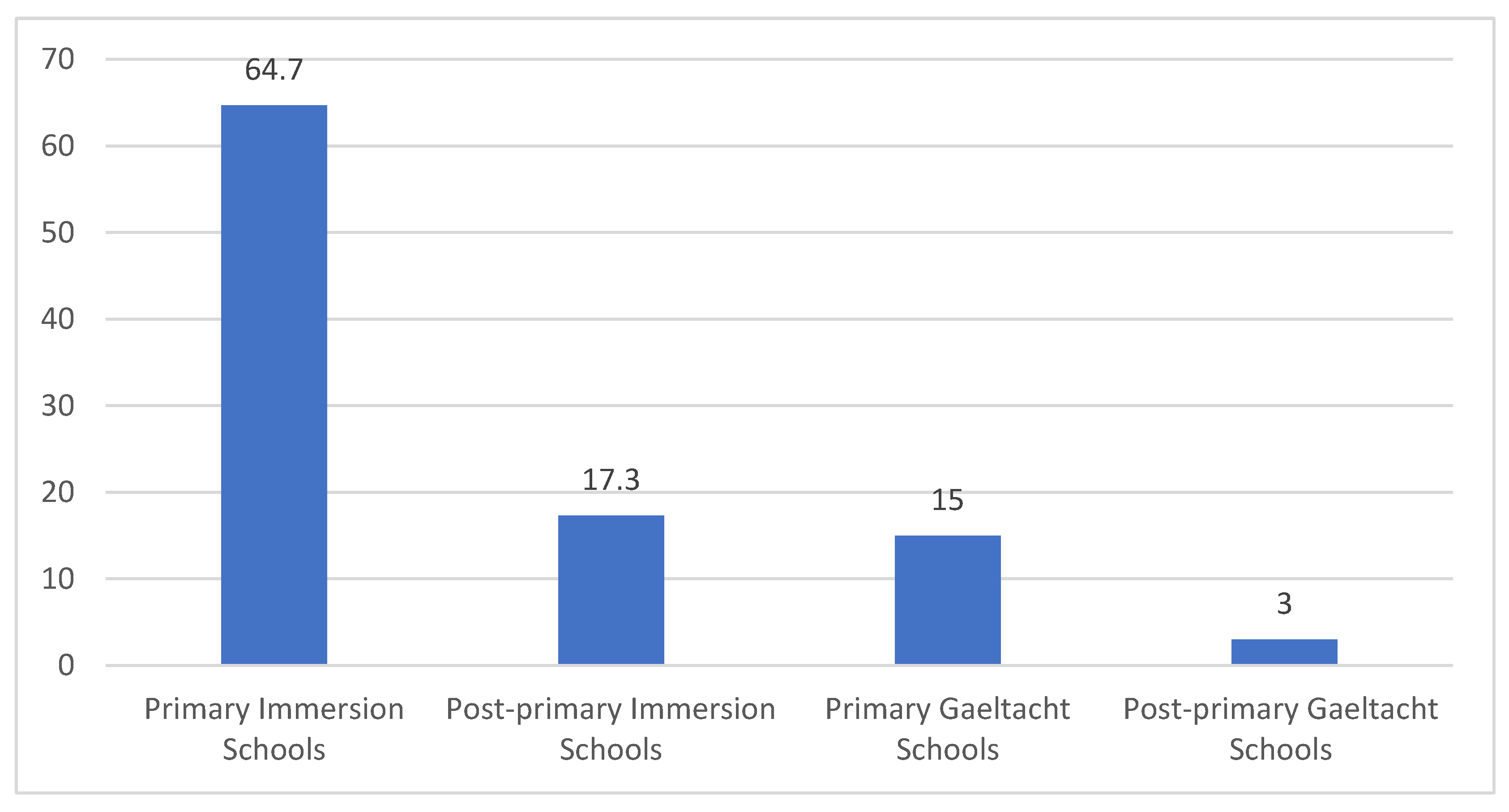

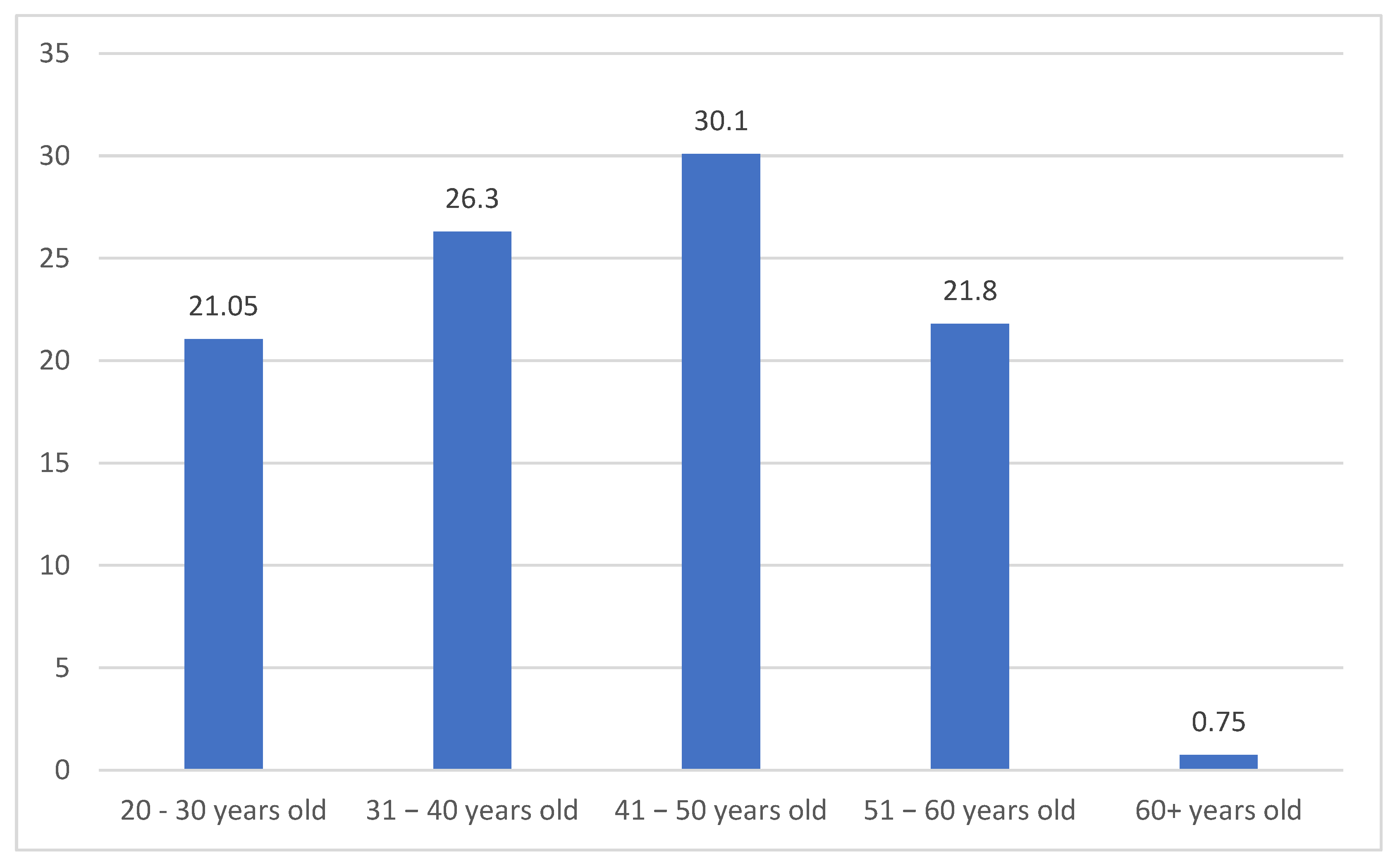

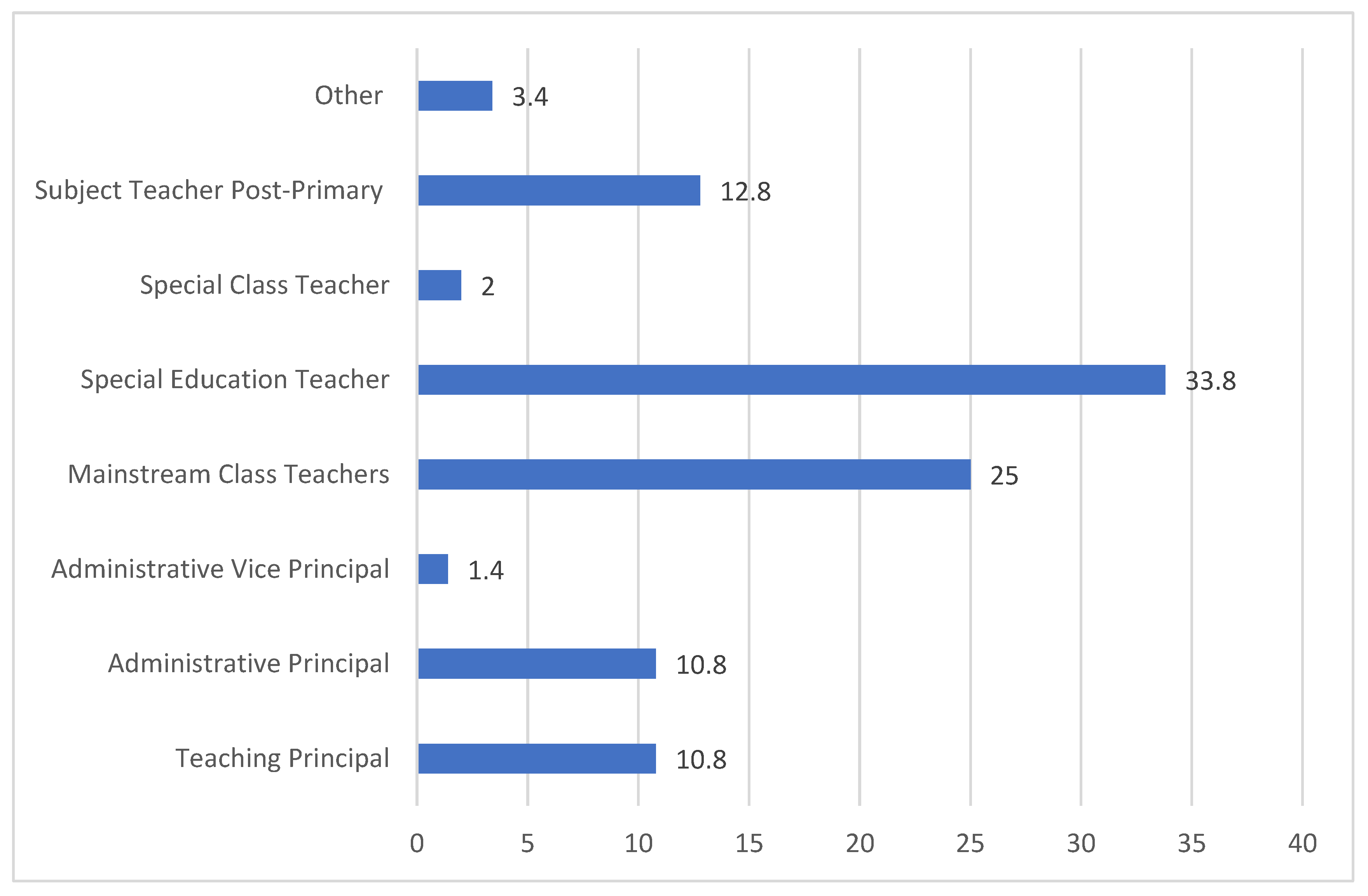

2.2. Participant Profiles

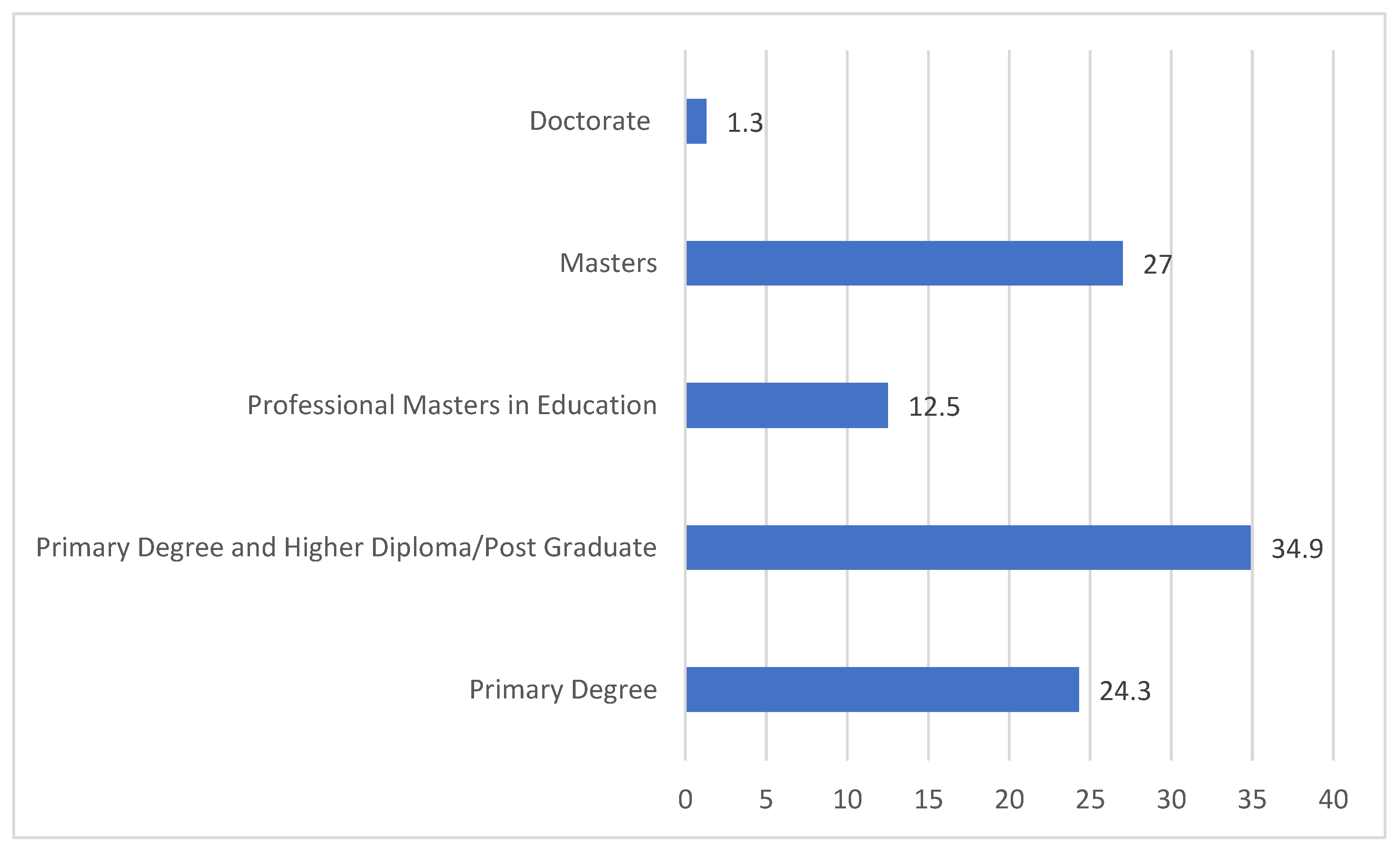

2.3. Teaching Experience and Qualifications of Participants

3. Results

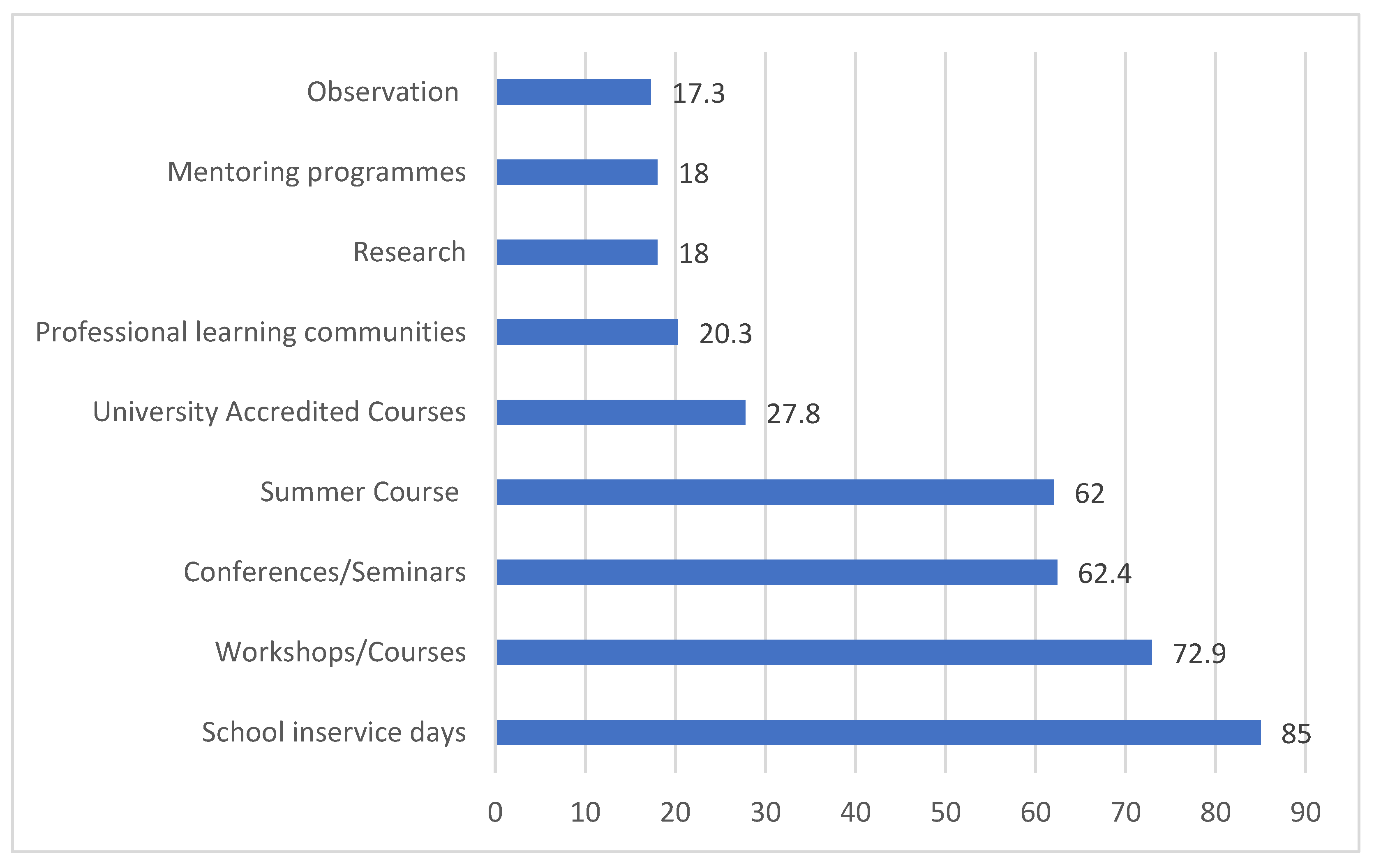

3.1. Previous CPD in Special Education

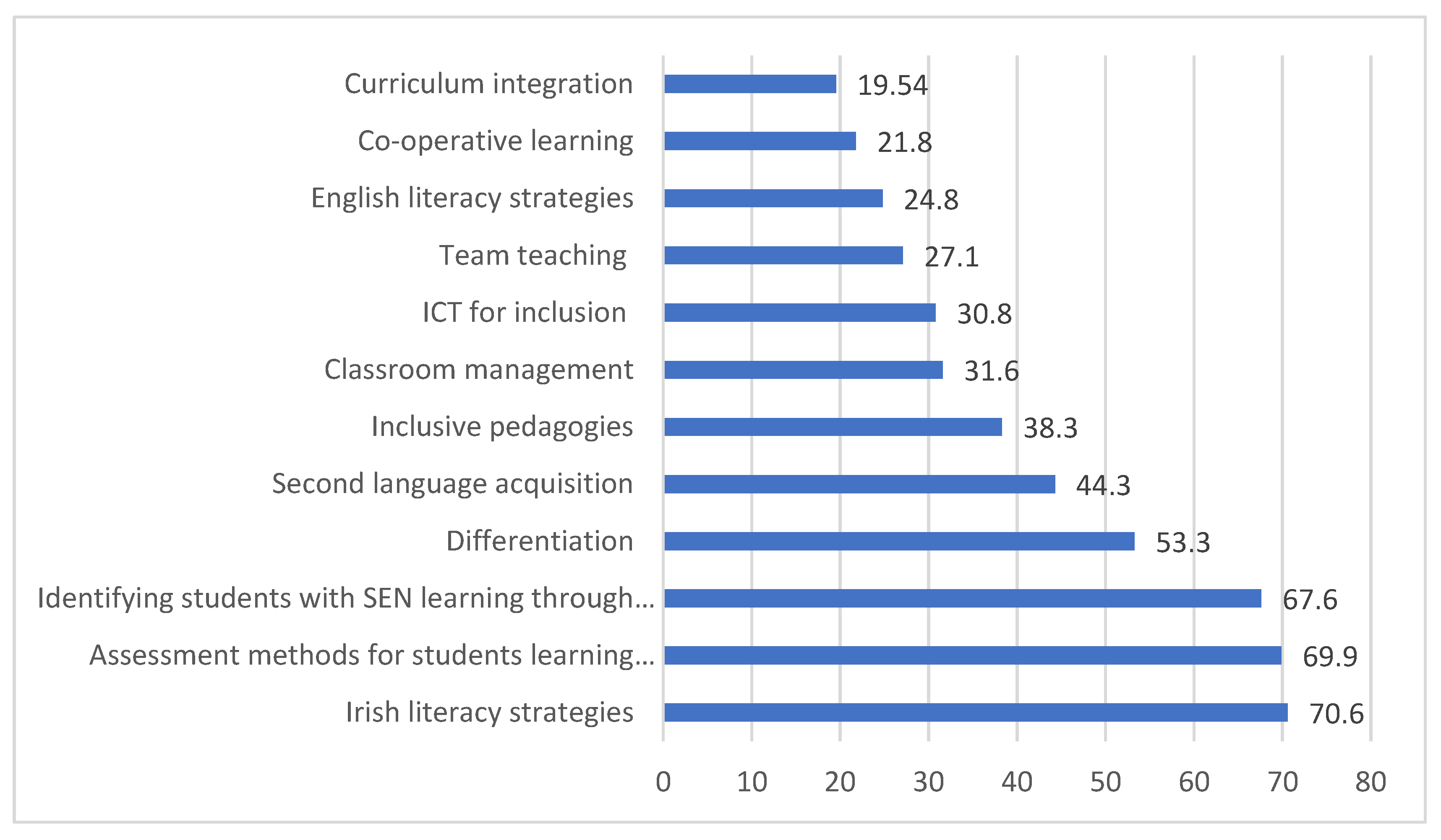

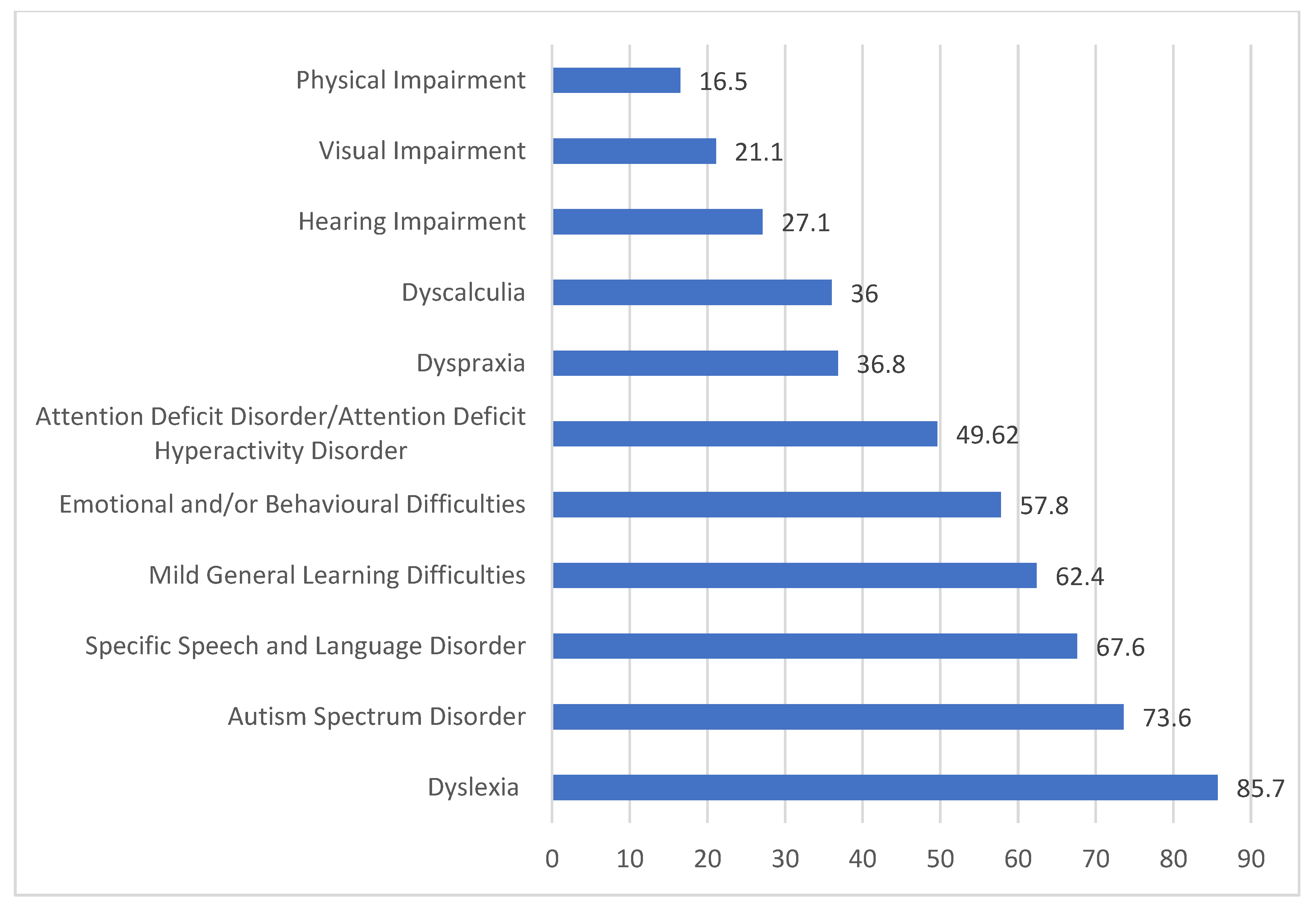

3.2. The CPD Needs of Teachers in Special Education

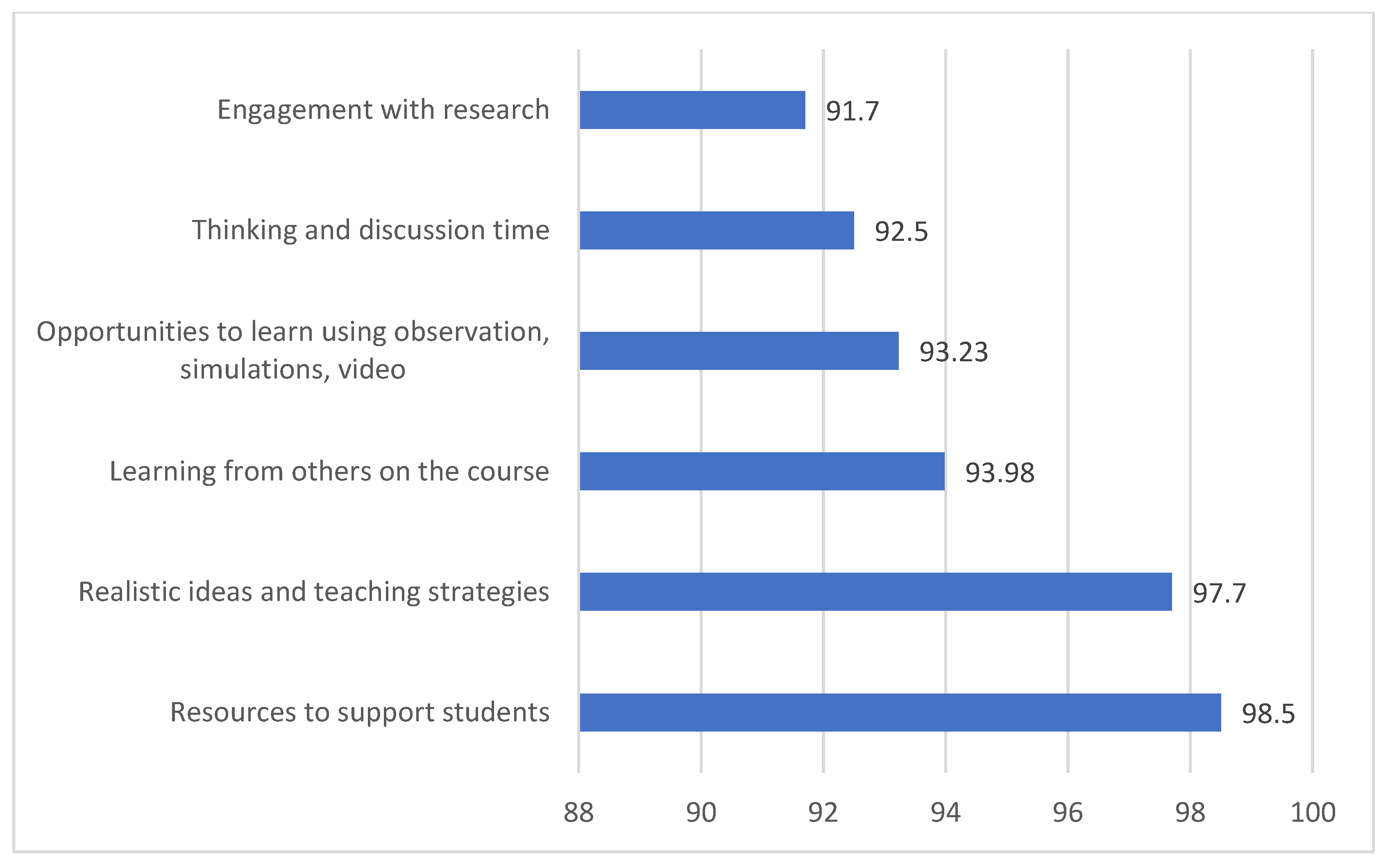

3.3. CPD Course Design

3.4. The Reasons Teachers Want to Undertake CPD in This Area

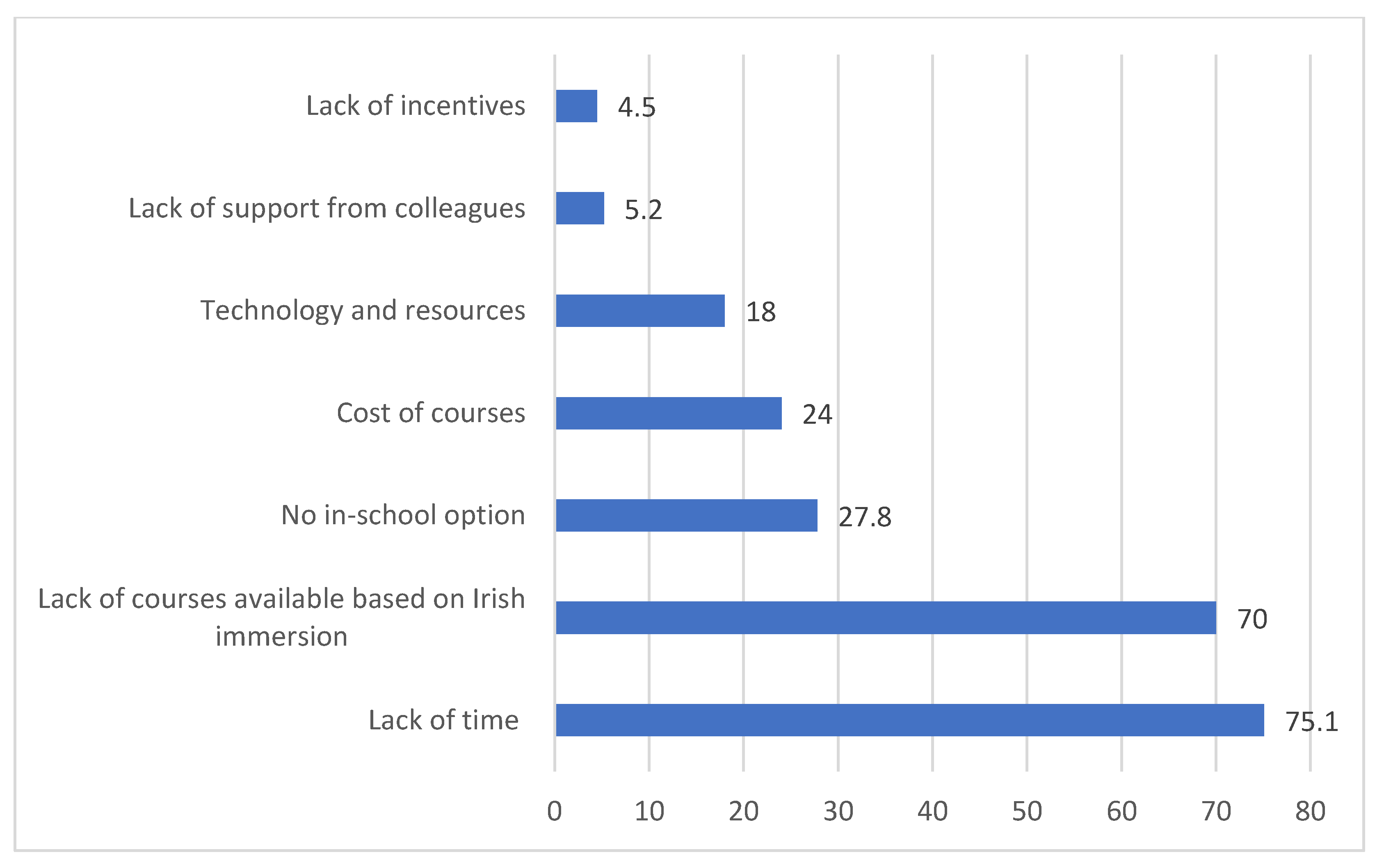

3.5. The Challenges of Accessing CPD

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muller, J. Riachtanais Speisialta Oideachais i Scoileanna ina Bhfuil an Ghaeilge mar Mheán (Special Educational Needs in Schools Where Irish Is the Medium); An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta: Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. The Additional Supports Required by Pupils with Special Educational in Irish-Medium Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland, 1 February 2020. Available online: http://doras.dcu.ie/24100/1/Sin%C3%A9ad%20Andrews%20PhD%20Final%20.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- NCCA. Language and Literacy in Irish-Medium Primary Schools: Supporting School Policy and Practice; National Council for Curriculum and Assessment: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M. Doras Feasa Fiafraí: Exploring Special Educational Needs Provision and Practices Across Gaelscoileanna and Gaeltacht Primary Schools in the Republic of Ireland; University College Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Chinnéide, D. The Special Educational Needs of Bilingual (Irish-English) Children; POBAL: Education and Training: Belfast, Northern Ireland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Donnacha, S.; Ní Chualáin, F.; Ní Shéaghdha, A.; Ní Mhainín, T. Staid Reatha na Scoileanna Gaeltachta: A Study of Gaeltacht Schools 2004; An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Thuairisg, L. It was two hours […] the same old thing and nothing came of it: Continuing professional development among teachers in Gaeltacht post-primary schools. J. Immers. Content-Based Lang. Educ. 2018, 6, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Sass, T.R. What Makes Special Education Teachers Special? Teacher Training and Achievement of Students with Disabilities: Working Paper49; National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research: Stanford, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paneque, O.M.; Rodriguez, D. Language Use by Bilingual Special Educators of ELLs with Disabilities. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2009, 24, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Artiles, A.J.; Kozleski, E.B.; Trent, S.C.; Osher, D.; Ortiz, A. Justifying and Explaining Disproportionality, 1968–2008: A Critique of Underlying Views of c. Except. Child. 2010, 76, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Ó Duibhir, P.; Travers, J. The Prevalence and types of special educational needs in Irish immersion primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 35, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minihan, E.; Adamis, D.; Dunleavy, M.; Martin, A.; Gavin, B.; McNicholas, F. COVID-19 related occupational stress in teachers in Ireland. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2022, 3, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeloideachas. Statisitcs. 2020. Available online: https://gaeloideachas.ie/i-am-a-researcher/statistics/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Department of Education and Skills. Policy on Gaeltacht Education: 2017–2022; Department of Education and Skills: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, L.; Seoighe, A. Educational psychological provision in Irish-medium primary schools in indigenous Irish language speaking communities (Gaeltacht): Views of teachers and educational psychologists. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 1278–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Giollagáin, C.; Mac Donnacha, S.; Ní Chualáin, F.; Ní Shéaghdha, A.; O’Brien, M. Comprehensive Linguistic Study of the Use of Irish in the Gaeltacht; Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs: Galway, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Giollagáin, C.; Charlton, M. Nuashonrú ar an Staidéar Cuimsitheach Teangeolaíoch ar Úsáid na Gaeilge sa Ghaeltacht: 2006–2011; Update on the Comprehensive Linguistic Study on the Use of Irish in the Gaeltacht 2006–2011; Údarás na Gaeltachta: Furbo, Galway, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McAdory, S.E.; Janmaat, J.G. Trends in Irish-medium education in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland since 1920: Shifting agents and explanations. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2015, 36, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment, N.C.f.C.a. Primary Language Curriculum; NCCA: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M.; Kinsella, W.; Prendeville, P. Special educational needs in bilingual primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2019, 39, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Aindriú, S.; Ó Duibhir, P.; Travers, J. A survey of assessment and additional teaching support in Irish immersion education. Languages 2021, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nic Gabhann, D. Special Educational Needs in Gaelscoileanna. Master’s Thesis, University of Wales, Bangor, Wales, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S. A Study on the Prevalence of Special Educational Needs; National Council for Special Education: Co. Meath, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, J.; Genesee, F.; Crago, M.B. Dual Language Development and Disorders: A Handbook on Bilingualism and Second Language Learning; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, F. Another view of bilingualsm. In Cognitive Processing in Bilinguals; Harris, R., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, Holland, 1992; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kay-Raining Bird, E.; Genesee, F.; Verhoeven, L. Bilingualism in children with developmental disorders: A narrative review. J. Commun. Disord. 2016, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Sebastián-Gallés, N. How does the bilingual experience sculpt the brain? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garraffa, M.; Beveridge, M.; Sorace, A. Linguistic and cognitive skills in Sardinian–Italian bilingual children. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberman, Z.; Woodward, A.L.; Keysar, B.; Kinzler, K.D. Exposure to multiple languages enhances communication skills in infancy. Dev. Sci. 2017, 20, e12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, E.J.; Bearse, C.I. The same outcomes for all? High school students reflect on their two-way immersion program experiences. In Immersion Education: Pathways to Bilingualism and Beyond; Tedick, D.J., Christian, D., Fortune, T.W., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2011; pp. 104–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E. Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2009, 12, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormi-Nouri, R.; Moradi, A.-R.; Moradi, S.; Akbari-Zardkhaneh, S.; Zahedian, H. The effect of bilingualism on letter and category fluency tasks in primary school children: Advantage or disadvantage? Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2012, 15, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portocarrero, J.S.; Burright, R.G.; Donovick, P.J. Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2007, 22, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barac, R.; Bialystok, E. Bilingual effects on cognitive and linguistic development: Role of language, cultural background, and education. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, E.B.; Gollan, T.H. Being and becoming bilingual: Individual differences and consequences for language production. In Handbook of Bilingualism: Psycholinguistic Approaches; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Oller, D.K.; Pearson, B.Z.; Cobo-Lewis, A.B. Profile effects in early bilingual language and literacy. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2007, 28, 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Wei, L. Individual differences in the lexical development of French–English bilingual children. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2008, 11, 598–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin-Dubois, D.; Bialystok, E.; Blaye, A.; Polonia, A.; Yott, J. Lexical access and vocabulary development in very young bilinguals. Int. J. Billing 2013, 17, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legacy, J.; Zesiger, P.; Friend, M.; Poulin-Dubois, D. Vocabulary size and speed of word recognition in very young French–English bilinguals: A longitudinal study. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2018, 21, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay-Raining Bird, E.; Cleave, P.; Trudeau, N.; Thordardottir, E.; Sutton, A.; Thorpe, A. The language abilities of bilingual children with Down Syndrome. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2005, 14, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.M.; Kohlmeier, T.L.; Durán, L.K. Comparative language development in bilingual and monolingual children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. J. Early Interv. 2017, 39, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genesee, F.; Lindholm-Leary, K. The suitability of dual language education for diverse students: An overview of research in Canada and the United States. J. Immers. Content-Based Lang. Educ. 2021, 9, 164–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Valenzuela, J.S.; Bird, E.K.; Parkington, K.; Mirenda, P.; Cain, K.; MacLeod, A.A.; Segers, E. Access to opportunities for bilingualism for individuals with developmental disabilities: Key informant interviews. J. Commun. Disord. 2016, 63, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, P.; Dunlap, K.; Brister, H.; Davidson, M.; Starrett, T.M. Sink or swim? Throw us a life jacket! Novice alternatively certified bilingual and special education teachers deserve options. Educ. Urban Soc. 2013, 45, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.G.; Kohler, P.D. The state of school-based bilingual assessment: Actual practice versus recommended guidelines. Lang Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2007, 38, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Scott, C. Formative assessment in language education policies: Emerging lessons from Wales and Scotland. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2009, 29, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N.; Chen, X. At-risk readers in French immersion: Early identification and early intervention. Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 2010, 13, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, L.; Hickey, T.M. ‘You’re looking at this different language and it freezes you out straight away’: Identifying challenges to parental involvement among immersion parents. Lang. Educ. 2013, 27, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkler, B. A review of literature on Hispanic/Latino parent involvement in K-12 education. 2002. Turney, K.; Kao, G. Barriers to school involvement: Are immigrant parents disadvantaged? J. Educ. Res. 2009, 102, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genesee, F.; Fortune, T.W. Bilingual education and at-risk students. J. Immers. Content-Based Lang. Educ. 2014, 2, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Duibhir, P.; Ó Cathalláin, S.; NigUidhir, G.; Ní Thuairisg, L.; Cosgrove, J. An Analysis of Models of Provision for Irish-Medium Education; An Coiste Seasta Thuaidh Theas ar an nGaeloideachas: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa, A.; Brandon, R.R.; Cadiero-Kaplan, K.; Ramirez, P.C. Bridging bilingual and special education: Opportunities for transformative change in teacher preparation programs. Assoc. Mex. Am. Educ. J. 2014, 8, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, D.; Carrasquillo, A. Bilingual special education teacher preparation: A conceptual framework. NYSABE 1997, 12, 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, D. A conceptual framework of bilingual special education teacher programs. In ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, Somerville, MA, USA, 30 April–3 May 2005; Cohen, J., McAlister, K.T., Rolstad, K., MacSwan, J., Eds.; Cascadilla Press: Somerville, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 1960–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarata, L.; Tedick, D.J. Balancing content and language in instruction: The experience of immersion teachers. Mod. Lang. J. 2012, 96, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S. Indigenous immersion education: International developments. J. Immers. Content-Based Lang. Educ. 2013, 1, 34–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, D.B. Four Successful Indigenous Language Programs. In Teaching Indigenous Languages; Reyhner, J., Ed.; Northern Arizona University: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 1997; pp. 248–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Grádaigh, S. Who are qualified to teach in second-level Irish-medium schools? Ir. Educ. Stud. 2015, 34, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Teaching Council. Initial Teacher Education: Criteria and Guidelines for Programme Providers; The Teaching Council: Maynooth, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Teaching Council. Cosán: Framework for Teacher’s Learning; The Teaching Council: Maynooth, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, J.; Balfe, T.; Butler, C.; Day, T.; Dupont, M.; McDaid, R.; O’Donnell, M.; Prunty, A. Addressing the Challenges and Barriers to Inclusion in Irish Schools: Report to Research and Development Committee of the Department of Education and Skills; Department of Education and Skills: Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. Provider’s Booklet for Summer Courses 2021; Department of Education: Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.J.; McConnell, B.; O’Sullivan, H. Continuing professional development-why bother? Perceptions and motivations of teachers in Ireland. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2016, 42, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University College London (UCL). Designing Programmes and Modules with ABC Curriculum Design. 2022. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/teaching-learning/case-studies/2018/jun/designing-programmes-and-modules-abc-curriculum-design (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- DuFour, R. What’s a professional learning community? Educ. Leadersh. 2004, 61, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

| Outside the Gaeltacht | Gaeltacht Areas | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary School Students | 37,243 | 7059 | 44,302 |

| No. of Primary Schools | 151 | 101 | 252 |

| Post-Primary Students | 10,498 | 3602 | 14,100 |

| No. of Post-Primary Schools | 47 | 21 | 68 |

| Questionnaire Theme | Sources of Literature |

|---|---|

| Age range and years teaching experience. | OECD 2008, 2013, 2014 |

| Type of position they held in their school. | OECD 2008, 2013, 2014 |

| Their level of teacher training/education. | OECD, 2008, 2013, 2014 |

| Previous CPD. | OECD, 2008, 2013, 2014 |

| The areas of special education in which they would like more CPD. | Andrews (2020), Barrett, Williams, Kinsella, 2020; Nic Aindriú et al., 2020 |

| The aspects of CPD course development that are most relevant for them. | OECD, 2008, 2013, 2014 |

| The way they would like to access CPD in this area (e.g., online, face-to-face, blended learning). | OECD, 2008, 2013, 2014 |

| Their motivations for undertaking CPD in this area. | Ní Thuairisg, 2018; McMillan, McConnell & O’Sullivan, 2016 |

| The barriers they face when accessing CPD in this area. | Ní Thuairisg, 2018; McMillan, McConnell & O’Sullivan, 2016 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nic Aindriú, S.; Duibhir, P.Ó.; Connaughton-Crean, L.; Travers, J. The CPD Needs of Irish-Medium Primary and Post-Primary Teachers in Special Education. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120909

Nic Aindriú S, Duibhir PÓ, Connaughton-Crean L, Travers J. The CPD Needs of Irish-Medium Primary and Post-Primary Teachers in Special Education. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):909. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120909

Chicago/Turabian StyleNic Aindriú, Sinéad, Pádraig Ó Duibhir, Lorraine Connaughton-Crean, and Joe Travers. 2022. "The CPD Needs of Irish-Medium Primary and Post-Primary Teachers in Special Education" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120909

APA StyleNic Aindriú, S., Duibhir, P. Ó., Connaughton-Crean, L., & Travers, J. (2022). The CPD Needs of Irish-Medium Primary and Post-Primary Teachers in Special Education. Education Sciences, 12(12), 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120909