Pocket Restorative Practice Approaches to Foster Peer-Based Relationships and Positive Development in Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

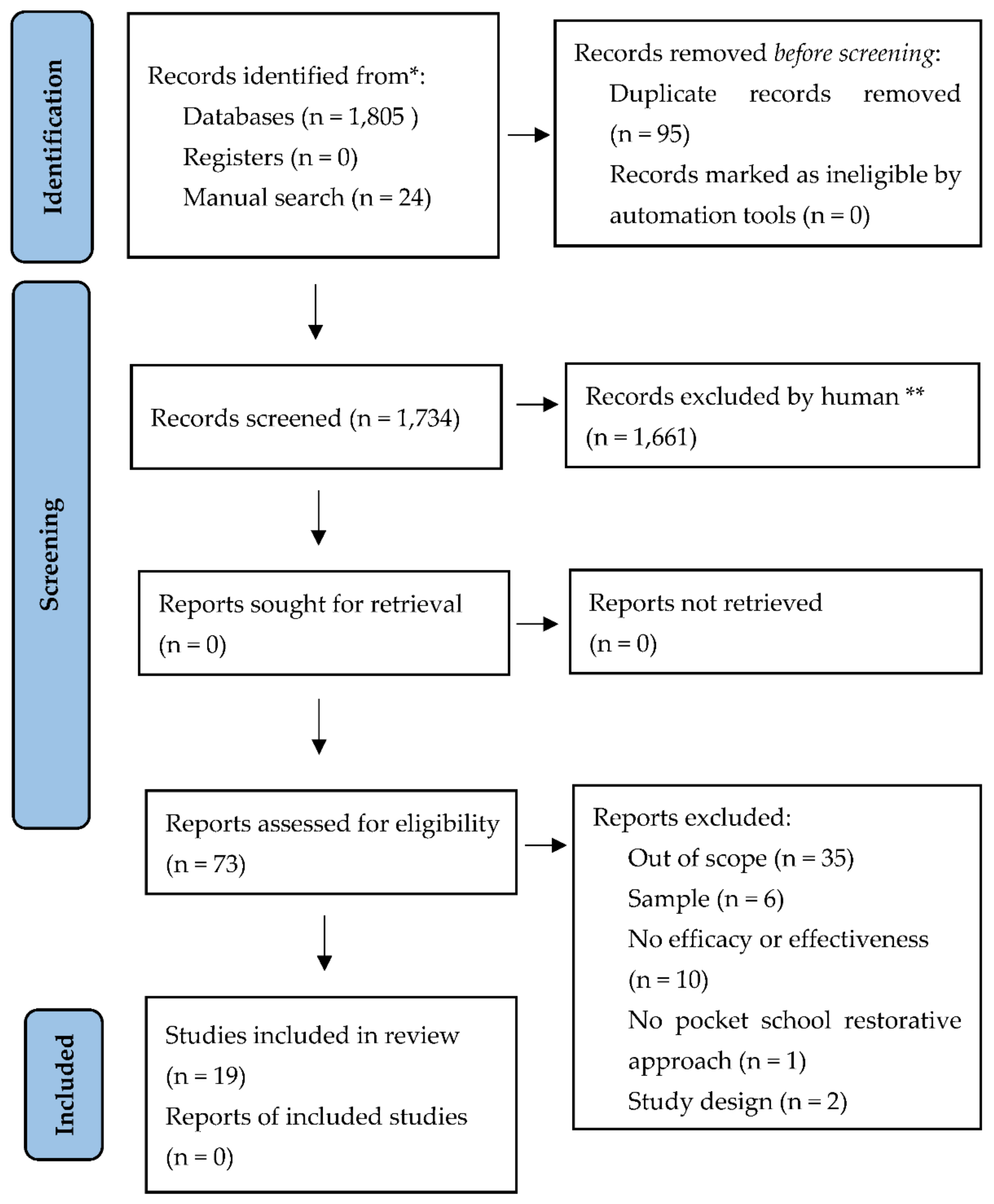

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Procedure

2.2. Synthesis of Data

3. Results

3.1. Overall Results

3.2. Pocket School Restorative Approaches: Evidence Available, Its Quality and Development of Evidence-Based Guidelines

3.2.1. Mediation

- The CRPM program is recommended in primary education to reduce levels of aggression of students with lower socio-economic level [26] (Grade of recommendation: B);

- Mediation is recommended in secondary education to improve school climate, interpersonal relationships between a diverse population of students and teachers, while decreasing the incidence of conflicts among such a population [27] (Grade of recommendation: D).

3.2.2. Conferencing

- Restorative group conferencing is recommended in secondary education to deal with conflicts and prevent expulsions [28] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- Conferencing based on the traditional Māori protocol is recommended in secondary education for a diverse community of students for the improvement of behavior in the short term. Specifically, it is recommended to address and resolve tensions, make justice evident and fruitful, and support the restoration of harmony between a diverse community of students [29,30] (Grade of recommendation: D).

3.2.3. Class Meetings

- Class meetings are recommended in secondary education for students at risk of disengaging with education to help them develop greater skills in relating to others as well as in active listening and contributing appropriately and confidently [31] (Grade of recommendation: D).

3.2.4. Circles: Proactive type

- Talking circles are recommended for girls in multi-ethnic secondary educational centers to improve listening, anger management, empathic skills, and self-efficacy [32] (Grade of recommendation: D).

3.2.5. Circles: Reactive Type

- Restorative circles are recommended in primary and secondary education for the development of empathy, respect, values, attitudes, modes of behavior, and ways of life. Restorative circles are also recommended to help students in primary and secondary education to promote a school culture of peace [33] (Grade of recommendation: D);

- Restorative circles are recommended in secondary education for helping students to take ownership of their behavior, interrupting the school-to-prison pipeline, improving relationships as well as ways of handling conflict and engaging in significant dialogue [35] (Grade of recommendation: D);

- Restorative justice peer circles along with counter-story telling are recommended in secondary education for students at risk of dropping out of school in order to improve self-esteem, community support and academic performance [35] (Grade of recommendation: D).

3.2.6. Proactive Circles plus Reactive Circles

- The implementation of peace-making circles plus community circles is recommended to decrease discipline referrals and suspensions, while improving students’ social and emotional skills such as empathy and conflict resolution [36] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- The implementation of community-building circles plus restorative circles along with restorative conversations is recommended in secondary education in order to improve relationships between students and teachers and academic outcomes [37] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- The implementation of weekly program-wide talking circles and smaller healing circles for conflicts is recommended in secondary education for students at risk of dropping out of school in order to develop and maintain relationships [38] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- The implementation of preventive circles plus circles to intervene in conflicts as a schoolwide strategy is recommended for students from urban and low-income schools to improve social and emotional skills, including communication, expression in terms of emotions and thoughts and perspective-taking, as well as to improve learning [39] (Grade of recommendation: D).

3.2.7. Restorative Conversations

- Restorative conversations are recommended in order to create a safe space for communication, develop problem-solving skills and increase motivation to attend school [40] (Grade of recommendation: D).

3.2.8. Specific Models

- The restorative justice plan is recommended for students in secondary education to decrease the frequency and severity of incidents of hazing and change the school culture of hazing [42] (Grade of recommendation: D);

- The Fairness Committee Model is recommended to encourage student voice, democratic participation and create a space of trust and confidence. It is also recommended to validate students’ worth and humanity, and prevent drop-out while allowing for academic re-socialization [41] (Grade of recommendation: D);

- It is recommended that teachers and students work collaboratively to create the respect agreement to develop active listening and create an environment of shared respect and inclusion [43] (Grade of recommendation: D).

- It is recommended to use letter writing with students to develop the competence of emotional regulation, including an understanding of the relationship between emotion, thinking and behavior, and acting consequently [43] (Grade of recommendation: D).

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First Author (Year) | Objective | Study Design | Sample and Setting | Intervention | Control Group | Follow-Up | Instruments | Data Analysis | Outcomes | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burssens (2006) [28] | Evaluate the application of a restorative group conferencing intervention for incidents of divergent nature in a school context between 2002 and 2004 | Qualitative study | n = 62 (14 victims, 9 offenders, 20 supporters of the victims, 9 parents of the offenders, 8 other supporters of the offenders and 2 absent victims). Secondary. | Conferencing | No | No | Observation, questionnaires, interviews and focus group. | Not reported | High satisfaction of participants; intervention eased or eliminatedtensions in a class/school. Victims’ expectations were met and intervention was seen as appropriate and fair. Intervention prevented expulsion. Confrontation between the offender and victim was seen as positive. | 3 |

| Carrasco (2016) [27] | Analyze the conflict scenarios in school samples | Qualitative study | n = 60 (teachers and students). Secondary. | Mediation | No | No | Observations, survey, focus groups, informal interviews, individual and group semi-structured interviews | Typology analysis | Improvement of school climate, interpersonal relationships between participants and very low incidence of conflicts among students. | 3 |

| Cavanagh (2009) [40] | Analyze the implementation of restorative practices in area school from 2004 through 2008 | Qualitative study | n = 96 (students from year 7 to 10) and n = 17 (teachers). Primary and secondary. | Restorative conversations | No | No | Reflective writing exercise and focused interviews | Levels of use interview procedure | Enhancement of student’s behavior problems and the relationships students -teachers; a schoolwide change sustained over a period of time | 3 |

| Cavanagh (2014) [37] | Focused on changing teachers’ practices; involving Latino/Hispanic students andtheir parents as primary informers in the process. | Qualitative study | n is not stated (students, teachers, parents). Secondary. | Circle proactive plus reactive types | No | No | Focus group interviews “testimonios” and teacher’s interviews | Typological analysis | Improvement in relationships between students and teachers and improvement in academic achievement. | 3 |

| DeWitt (2011) [42] | Ascertain if the restorative justice plan and thesubsequent ongoing education program altered the actions and beliefs of the studentsregarding hazing. | Qualitative study | n = 437 students. Secondary. | Restorative justice plan | No | No | Questionnaire | Frequencies and percentages of responses | Significant decrease in the number and severity of hazing incidents. Change in the school culture regarding the acceptance of hazing. | 3 |

| Gray (2011) [31] | Explore how the class meeting process might teach or provide opportunities for students to develop skills in the key competencies of participating and contributing and relating to others. | Qualitative study | n is not stated. A class (11 grade; 15–16-year-olds) took part in seven class meetings. A class of students was constructed to meet theneeds of a group of students who were at risk of disengaging with education due to previous problems with absenteeism, behavior, ongoing illness, and some individual learning needs. Secondary. | Class meetings | No | Yes | No instruments. | Video data of two class meetings, the first, and the last, were analyzed. To analyze the changes in students’ skills in the key competencies–relating to others and participating and contributing–certain behaviors or events within the meetings were named as indicators ofimprovement. | Development of greater skills of students in relating to others and participating and contributing (actively listening and contributing appropriately and confidently). | 3 |

| Gwathney (2021) [35] | To study the pathway of restorative justice as a tool to decrease inequities in zero-tolerance schoolsuspensions | Case study | n = 1. A 17-year-old African American male in his junior year of high school. He is the oldest of three siblings and resides in the custody of their maternal grandmother due to the incarceration of both parents. Secondary. | Circle reactive type | No | No | No instruments | Narrative | The subject experienced a decrease in suspensions, an increase in his sense of self-worth, academic progress, and community support. | 3 |

| Hantzopoulos (2013) [41] | Examined how both current and former students made meaning of their experience at this school that emphasizes democratic and participatory practices | Qualitative study | n = 180 students. Secondary. | Specific models or plans | No | No | No instruments. | Data collected through participant observation at the school, interviews with former and current students, and surveys. | The Fairness Committee positively contributes to a safe environment and helps students grow personally. | 3 |

| Knight (2014) [38] | To evaluate critical restorative justice through peacemaking circles to nurture resilienceand open opportunity at the school level. | Qualitative study | n = about 60 students. A small learning community at a High School including students who have failed at least one grade level and have consistently been unsuccessful in school and/or are on the verge of dropping out. Secondary. | Circle proactive plus reactive types | No | No | No instruments | Narrative | Circles can be an equalizing and humanizing structure within schools that supports the development and maintenance of relationships. | 3 |

| Krieger (2012) [33] | To investigatethe prevalence of bullying and how restorative practices can help to deal with conflict. | Qualitative study | n = 40 (32 students and 8 teachers who were circle coordinators). Four schools. Primary and secondary. | Circle reactive type | No | No | Self-administered questionnaire based on Fante (2005). | Data collection was performed using a specific questionnaire based on Fante (2005), and another self-applied questionnaire. | Restorative circles can be implemented in schools as an alternative to conflict and violent situations associated with bullying. Students learn empathy, respect, values, attitudes, modes of behavior, and ways of life. Restorative circle stimulated other measures to promote a culture of peace and non-violence in school setting. Restorative circles help students to promote a healthier and peaceful school environment. | 3 |

| Norris (2019) [15] | To evaluate thepotential effects of restorative practice approaches on well-being, specifically, happiness andschool engagement. | Quasi-experimental | n = 19 (15 males and 4 females). Not stated. | Conferencing | No | Yes | - Subjective Happiness Scale (Happiness). Excellent reliability and construct validity. - School Engagement Scale (Schoolengagement). Reliability and validity measures are not reported. Self-report measures. | Use of inferential statistics to stablish any significant differences between Time 1 and Time 2. Use of dependent sample t-tests to establish any significant differences between Time 1 and Time 2. | No significant differences in happiness or school engagement across time. | 2− |

| Ortega (2016) [34] | To understand how staff and students experience the restorative circle program at their school and also what outcomes they report as a result of the program | Qualitative study | n = 35 students (20 female and 15 male) and 25 school staff (16 female and 9 male). Secondary. | Circle reactive type | No | No | Semi structured interview with 14 open-ended questions grouped in three major sections: (a) questions about conflict in general (e.g., “What do you do when you have a conflict with anotherstudent at school?”), (b) questions about the RC program (e.g.,“Tell me about your circle experience”), and (c) questions aboutschool conflict (e.g., “What should teachers do when students haveconflict with each other at school”). | Qualitative (thematic analysis) | Two categories: (A) Negative outcomes > 1: frustration particularly by lying and fighting; and 2: disappointment, including the theme of unwilling to be vulnerable and not everyone important to the conflict being present. (B) Positive outcomes > 1: taking ownership of process/bypassing adults; 2: interrupting the School-to-Prison Pipeline; 3: improving relationships; 4: preventing destructive ways of engaging conflict; and 5: meaningful dialogue. | 3 |

| Schumacher (2014) [32] | To evaluate whether out of-classroom Talking Circles might nurture long-termgrowth-fostering relationships that address gender-specificissues and encourage the development of emotional literacyskills. | Qualitative study | n = 60 girls ranging in age from 14 to 18. Secondary. | Circles proactive type | No | No | No instruments | Qualitative (observations of257 hrs. of Talking Circles; individual semi-structured interviews andarchival documents) | Four themes: (1) the joy of being together and building relationships; (2) a sense of safety grounded in trust, confidentiality, not feeling alone, and not being judged; (3) freedom to express genuine emotions; and (4) increased empathy and compassion. Improvement of the capacity to listen, manage anger, and interpersonal sensitivity. | 3 |

| Skrzypek (2020) [39] | To explore restorative practice circle experiences of urban, low-income, andpredominantly Black middle school students with attention to the diversity of their experiencesby grade level, race, and gender. | Qualitative design | n = 90 (49 students from fifth grade and 41 students from eighth grade). Primary and secondary. | Proactive plus reactive circles. | No | No | Two open-ended questions to gauge acceptability of restorative practices circles. | Two researchers independently reviewed and coded students’ qualitative responses by grade level. Coders then met to discuss their categorizations and revise initial codes to reach consensus between them. After they finalized codes, the coders noted the gender of participants and calculated the number of times themes were mentioned by gender and grade. We then reviewed for differences across those demographic categories. | Findings highlighted the benefits of restorative practice circles in promoting communication, expressing thoughts and feelings, perspective taking, and opportunity for learning | 3 |

| Stinchcomb (2006) [36] | Examine outcomes of applying restorative justice principles todisciplinary policies in educational settings | Mixed method design (quasi-experimental and qualitative) | n is not stated. Two elementary schools (School 1 and 2) and 1 junior high, School 3 (7th and 8th grade). Primary and secondary. | Proactive plus reactive circles. | No | No | No psychometric instruments. Questionnaires, observations, interview and focus groups, | Quantitative: Pre-post changes in the rates of suspensions, expulsions, behavior referrals, and attendance for all three schools. Qualitative: Experiential accounts | Decreases in discipline referrals and suspensions followed the schools’ adoption of restorative practices. The need for reactive practices decreased across implementation. Students tend to indicate that they like the fact that “things got resolved” and “everyone is treated equal.” In the healing tradition of circles, they also report a positive reaction to “seeing progress” firsthand and, for some, “getting my friends back. ”Students have expressed greater empathy for others and have noted that the circle helped them understand new ways of solving problems and moving forward. | 3 |

| Turnuklu (2010) [26] | This study aims to analyze the effects of conflict resolution and peer mediation(CRPM) training on the levels of aggression of 10–11-year-old Turkish primary school students | Quasi-experimental | Experimental group: n = 347 students of fourth-year and fifth-year (173 girls, 174 boys). Primary. | Mediation | Control group: n = 328 students of fourth-year and fifth-year (158 girls, 170 boys) | Yes | Aggression Scale developed by Sahin (2004). It is a Likert-type scale that includes 13 items. Participants answer the questions by marking one of the answers as ‘Always do’ (3), ‘Sometimes do’ (2), and ‘Never do’ (1). The maximum score in the instrument is 39, and the minimum is 13. A higher score indicates a higher level of aggression. The validity (construct and content validity) of the scale was analyzed. The internal consistency(Cronbach’s Alpha) of the scale was 0.77. The test-retest method was used to measure the reliability coefficient and the correlation of 0.71 was found. The reliability analysiswas repeated in the present study. The internal consistency value from the analysis of 675 students was 0.80 for the pre-test data, and 0.82 for the post-test. | The data collected were analyzed using statistical analysis techniques such as t-tests and one-way and two-way analysis of covariance. | Experimental intervention was found to reduce student aggression | 2++ |

| Wearmouth (2007) [29] | Discuss an example of restorative justice in practice to illustrate how community norms and values can help to encourage more socially appropriate behavior | Case study | n = 1 Secondary | Conferencing | No | No | No instruments | Narrative | Improved behavior, but no data | 3 |

| Wearmoth (2007) [30] | Discuss two examples of restorative justice in practice to illustrate how community norms and values can help to encourage more socially appropriate behavior | Case study. Case 1 the same as in Wearmoth et al., 2007b | n = 2. Secondary. | Conferencing | No | No | No instruments | Narrative | Improved behavior, but no data | 3 |

| Weaver (2020) [43] | This case study focused on exploring theimplementation of restorative justice disciplinepractices within a middle school. | Qualitative study | n = 6 students enrolled in classes whereteachers were using RJ practices for discipline. Secondary. Levels are not stated. | Specific models or plans | No | No | We collected data using three methods: (a) interviews, (b) observations, and (c) review ofdocuments. | Analysis of the data after the interviews were transcribed and the data were organized. This process involved: (1) coding the data individually; (2) analytic coding to combine similar codes into categories; (3) triangulation of data sources; and (4) development of themes and consensus about them. | The collaboration in creating the respect agreement allowsfor students and the teacher to share their ideas in an environment of mutual respect and inclusion. Students expressed appreciationfor the letter writing process, as it gave them an opportunity to examine their actions and to be intentional with their response. | 3 |

References

- Hurlbert, M. “Now Is the Time to Start Reconciliation, and We Are the People to Do So”, Walking the Path of an Anti-Racist White Ally. Societies 2022, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevington, T.J. Appreciative evaluation of restorative approaches in schools. Pastor. Care Educ. 2015, 33, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McCluskey, G. Exclusion from school: What can ‘‘included’’ pupils tell us? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 34, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute of Restorative Practices. What is restorative practices? 2007. Available online: www.iirp.org/whatisrp.php (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Lerner, R.M.; Brindis, C.D.; Batanova, M.; Blum, R.W. Adolescent health development: A relational developmental systems perspective. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Halfon, N., Forrest, C.B., Lerner, R.M., Faustman, E.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Expósito, L.; Krieger, V.; Amador-Campos, J.A.; Casañas, R.; Albertí, M.; Lalucat-Jo, L. Implementation of Whole School Restorative Approaches to Promote Positive Youth Development: Review of Relevant Literature and Practice Guidelines. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonell, C.; Allen, E.; Warren, E.; McGowan, J.; Bevilacqua, L.; Jamal, F.; Viner, R.M. Effects of the Learning Together intervention on bullying and aggression in English secondary schools (INCLUSIVE): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 8, 2452–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldys, P. Restorative practices: From candy and punishment to celebration and problem-solving circles. J. Character Educ. 2016, 12, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, E.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Viner, R.; Bonell, C. Using qualitative research to explore intervention mechanisms: Findings from the trial of the Learning Together whole-school health intervention. Trials 2020, 21, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, M.; Bourke-Taylor, H.; Broderick, D. Developing student social skills using restorative practices: A new framework called H.E.A.R.T. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, K.E. An exploration of the implementation of restorative justice in an Ontario public school. Can. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 119, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.S.; Cheng, C.H.; Ngan, R.M.; Ma, S.K. Program effectiveness of a Restorative Whole-school Approach for tackling school bullying in Hong Kong. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. 2011, 55, 846–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Restorative practices: The journey continues. Teach. Learn. Netw. 2007, 14, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, E.; Perrella, L.; Lepri, G.L.; Scarpa, M.L.; Patrizi, P. Use of Restorative Justice and Restorative Practices at School: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, H. The impact of restorative approaches on well-being: An evaluation of happiness and engagement in schools. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2009, 36, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwick, T.; Hahn, J.W.; Hassoun Ayoub, L. Fostering community, sharing power: Lessons for building restorative justice school cultures. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2019, 27, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Benson, J.B. Positive youth development: Research and applications for promoting thriving in adolescence. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2011, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, D. Can Restorative Practices Help to Reduce Disparities in School Discipline Data? A Review of the Literature. Multicult. Perspect. 2016, 18, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Vereenooghe, L. Reducing conflicts in school environments using restorative practices: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 1, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katic, B.; Alba, L.A.; Johnson, A.H. A Systematic Evaluation of Restorative Justice Practices: School Violence Prevention and Response. J. Sch. Violence 2020, 19, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakszeski, B.; Rutherford, L. Mind the Gap: A Systematic Review of Research on Restorative Practices in Schools. Sch. Psych. Rev. 2021, 50, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer’s Handbook; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Edinburgh, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin, A.E. (Ed.) Single-Case Research Designs: Methods for Clinical and Applied Settings; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnuklu, A.; Kacmaz, T.; Gurler, S.; Sevkin, B.; Turk, F.; Kalender, A.; Zengin, F. The effects of conflict resolution and peer mediation training on primary school students’ level of aggression. Education 3-13 2010, 38, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco Pons, S.; Villà Taberner, R.; Ponferrada Arteaga, M. Resistencias institucionales ante la mediación escolar. Una exploración en los escenarios de conflicto. Rev. Antropol. Soc. 2016, 25, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burssens, D.; Vettenburg, N. Restorative Group Conferencing at School: A Constructive Response to Serious Incidents. J. Sch. Violence 2006, 5, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearmouth, J.; McKinney, R.; Glynn, T. Restorative justice: Two examples from New Zealand schools. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2007, 34, 126–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearmouth, J.; Mckinney, R.; Glynn, T. Restorative justice in schools: A New Zealand example. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 49, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Drewery, W. Restorative practices meet key competencies: Class meetings as pedagogy. Int. J. Sch. Disaffection 2011, 8, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, A. Talking Circles for Adolescent Girls in an Urban High School: A Restorative Practices Program for Building Friendships and Developing Emotional Literacy Skills. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger Grossi, P.; Mendes dos Santos, A. Bullying in Brazilian Schools and Restorative Practices. Can. J. Educ. 2012, 35, 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, L.; Lyubansky, M.; Nettles, S.; Espelage, D.L. Outcomes of a restorative circles program in a high school setting. Psychol. Violence 2016, 6, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwathney, A.N. Offsetting Racial Divides: Adolescent African American Males & Restorative Justice Practices. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2021, 49, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcomb, J.B.; Bazemore, G.; Riestenberg, N. Beyond zero tolerance. Restoring Justice in Secondary Schools. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2006, 4, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, T.; Vigil, P.; Garcia, E. A Story Legitimating the Voices of Latino/Hispanic Students and their Parents: Creating a Restorative Justice Response to Wrongdoing and Conflict in Schools. Equity Excell. Educ. 2014, 47, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.; Wadhwa, A. Expanding Opportunity through Critical Restorative Justice: Portraits of Resilience at the Individual and School Level. Schools 2014, 11, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, C.; Bascug, E.W.; Annahita, B.; Wooksoo, E.; Diane, K. In Their Own Words: Student Perceptions of Restorative Practices. Child. Sch. 2020, 42, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, T. Restorative Practices in Schools: Breaking the Cycle of Student Involvement in Child Welfare and Legal Systems. Prot. Child. 2009, 24, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hantzopoulos, M. The Fairness Committee: Restorative Justice in a Small Urban Public High School. Prev. Res. 2013, 20, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, D.M.; DeWitt, L.J. A Case of High School Hazing: Applying Restorative Justice to Promote Organizational Learning. NASSP Bull. 2012, 96, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.L.; Swank, J.M. A Case Study of the Implementation of Restorative Justice in a Middle School. RMLE Online 2020, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, D.R.; Breslin, B. Restorative Justice in School Communities. Youth Soc. 2001, 33, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, G.; Gwynedd, L.; Jean, K.; Riddell, S.; Stead, J.; Weedon, E. Can restorative practices in schools make a difference? Educ. Rev. 2008, 60, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.K.; Strunk, K.O.; Dhaliwal, T.K. Justice for All? Suspension Bans and Restorative Justice Programs in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Peabody J. Educ. 2018, 93, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, J.; Lloyd, G.; McCluskey, G.; Maguire, R.; Riddell, S.; Stead, J.; Weedon, E. Generating an inclusive ethos? Exploring the impact of restorative practices in Scottish schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2009, 13, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, J.; Mills, K.; Neal, Z.; Neal, J.N.; Wilson, C.; McAlindon, K. Approaches to measuring use of research evidence in K-12 settings: A systematic review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumz, E.J.; Grant, C.L. Restorative Justice: A Systematic Review of the Social Work Literature. Fam. Soc. 2009, 90, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.A.; Welch, K. Modelling the effects of racial threat on punitive and restorative school discipline practices. Criminology 2010, 48, 1019–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H. Restorative Justice and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Review of Existing Literature. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.; Mee, M. Using Restorative Practices to Prepare Teachers to Meet the Needs of Young Adolescents. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaandering, D. Implementing restorative justice practice in schools: What pedagogy reveals. J. Peace Educ. 2014, 11, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustick, H. “Restorative Justice” or Restoring Order? Restorative School Discipline Practices in Urban Public Schools. Urban Educ. 2021, 56, 1269–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Levels of Evidence | |

|---|---|

| 1++ | High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs a or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews or RCTs with a low risk of bias |

| 1− | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews or RCTs with a high risk of bias |

| 2++ | High-quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort studies. High-quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2+ | Well-conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

| 2− | Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

| 3 | Non-analytic studies, e.g., case reports, case series |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

| Grades of recommendation | |

| A | At least one meta-analysis, systematic review or RCT rated as 1++ and directly applicable to the target population; or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results |

| B | A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1+ |

| C | A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++ |

| D | Evidence level 3 or 4; or extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+ |

| Name of Practice or Approach | Essential Elements | Practice Guidelines | Grade of Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation | |||

| Resolution and Peer Mediation Program [26] | Aim: to reduce levels of students’ aggression. Elements: A 31-class-hour training program covering four basic skills: (1) understanding the nature of interpersonal conflicts (9 h); (2) communication (4 h); (3) anger management (6 h); and (4) interpersonal conflict resolution (12 h). | Recommended in primary education to reduce levels of aggression of students with lower socio-economic level. | B |

| Mediation [27] | Aim: to help students manage conflicts in schools. Elements: 40 class-hour training program with modules and phases. Process: - Information and sensibilization about mediation including members of all school community. - Establishment of the group (35 participants) and 27 h of training (9 sessions/3 h): * 12 h of theory: (a) mediation and conflict; (b) communication; (c) alternatives and emotional education. * 3 h for organization and getting ready the school for mediation. * 10 h of practices to test the mediation service * 9 h to solve doubts about the implementation of the service and to evaluate the training. - Definitive mediation program including the annual planning, the persons in charge and the members of the school community that support plan. | Recommended in secondary education to improve school climate, interpersonal relationships between a diverse population of students and teachers; while decreasing the incidence of conflicts among such a population. | D |

| Conferencing | |||

| Restorative group conferencing [28] | Aim: to repair the consequences of an incident. Process: - All participants involved in the incident have an individual contact with a facilitator to clarify the aims, the rules and the willingness to participate. - In the first round, all participants are presented and the aims and rules are restated. All participants are asked to depict the incident consequences. - In the second round, participants seek ways for repairing the harm. The proposals are integrated into the restorative plan by the facilitator. - Informal meeting in which participants can talk with each other and recover from the session, and the restorative plan is signed by all participants. | Recommended in secondary education to deal with conflicts and prevent expulsions. | D |

| Conferencing based on a traditional Māori protocol [29,30] | Aim: to restore the consequences of an incident. Process: (1) Prayers and greetings to acknowledge the attendance and respect of all participants; (2) “The problem is the problem”; the sentence is written on the board or spoken about; Each participant may reply to: - “What are you hoping to see happen in this meeting?” - “What is the problem that has brought us here?” - “What are the effects of that problem on all present?” - “What times, places and relationships do we know of where the problem is not present?” - “What new description of the people involved becomes clear as we look at the times and places where the problem is not present?” - “If there have been people/things harmed by the problem, what is it that you need to happen to see amends being made?” - “How does what we have spoken about and seen in the alternative descriptions help us plan to overcome the problem?” - “Does that plan meet the needs of anyone harmed by the problem?” (3) Participants are given responsibility to carry out a part of the plan. Follow ups are planned. (4) Prayers, thanks and hospitality are offered. | Recommended in secondary education for a diverse community of students to address and resolve tensions, make justice evident and fruitful, and support the restoration of harmony between a diverse community of students. | D |

| Formal conferencing [15] | Aim: to promote student participation and repair relationships damaged when a conflict occurs. Process: - Initial and preparatory meetings - Archetypal restorative conferencing - Follow up meetings No further details are provided. | No evidence in favor of its effects. No recommendation can be elaborated. | |

| Class meetings | |||

| Class meetings [31] | Aim: To solve problems in classrooms such as a difficult learning environment or lack of respect. Elements: - The facilitator that makes questions, sets the setting and runs the circle. - The reflector that writes down responses, feeds them back at the end of rounds and makes comments/challenge/ or unpack on discourses. - Discursive theoretical approach and elements of class conference and circle time. Process: - Four rounds, each beginning with a question. Students contribute their answers to the questions as they go around the circle in successive rounds. | Recommended in secondary education for students at risk of disengaging with education for the development of interpersonal skills as well as of active listening and contributing appropriately and confidently. | D |

| Circles proactive type | |||

| Talking circles [32] | Aim: A consensus-building, egalitarian process. It establishes a communication style that supports respect. Elements: - A talking piece that goes from one person to the next. Only the person holding it may speak. - Guidelines: speaking honestly, listening and no interrupting, and keeping confidentiality. - The Keeper preserves the circle integrity by modeling the guidelines. Process: - Four parts: (a) “checking in” (sharing moods); (b) “burning issues” (sharing problems); (c) “topic of the day” (discussing student-generated themes); and d) “closing” (reading inspiring quotes or making a wish for the week). | Recommended for girls in multi-ethnic secondary educational centers to improve listening, anger management, and empathic skills, and, thus, self-efficacy. | D |

| Circles reactive type | |||

| Restorative circle [33] | Aim: To support victims of bullying, to encourage the bullies to make amends and change behavior, and to determine how to best address the underlying problems. Process: - Circles are open to all involved parties. All parties will be able to speak and are expected to participate in the decision-making. - Decisions must be acceptable to everyone and include the interests of everyone. So, everyone has a role in success. | Recommended in primary and secondary education for the development of empathy, respect, values, attitudes, modes of behavior, and ways of life. Restorative circles are recommended as well to help students in primary and secondary education to promote a school culture of peace. | D |

| Restorative circle [34] | Aims: To solve an act of harm in a space that promotes understanding, self-responsibility and action. The act can be anything specifically observable that occurred and is used as a gateway into the conflict. Elements: - The facilitator. He/she invites those involved to participate. - Participants: (a) the “author”; (b) the “receiver”; and (d) the “community”. - Anyone can initiate a circle. Process: - The facilitator conducts separate preparatory meetings with all participants. The meetings take place to build connections, identify feelings and needs, explain the process, and obtain individual consent. - A dialogue is facilitated in which all individuals are supported by the facilitator in understanding each other, taking responsibility for their choices, and generating actions or agreements for moving forward. It makes use of the reflection process. Participants are asked to reflect back. - Post-circles take place to check agreements and how things are. | Recommended in secondary education for students to taking ownership of their behavior, interrupting the School-to-Prison Pipeline, improving relationships as well as ways of engaging conflict and significant dialogue. | D |

| Restorative justice peer circles [35] | Aims: establish group goals, connections, and personal narratives. Elements: - A facilitator who actively model ways to empathically acknowledge and validate students’ thoughts, feelings and experiences. - Students seated in circle in a private conference room to facilitate rapport, trust, and cohesiveness. - Counter-storytelling. Process: - At the start of each session (40-min.), students are informed of privacy, confidentiality, and objectives. - Students are provided sentence starters based on their own experiences. - Students are guided to explore and recognize participants’ strengths and positive character traits. | Recommended along with counter-story telling in secondary education for students at risk of dropping out school in order to improve self-esteem, community support and academic performance. | D |

| Proactive circles plus reactive circles | |||

| Community circles plus peacemaking circles [36] | Peacemaking circles Aims: to bring together victims, offenders, their families and other supporters, and community stakeholders to determine the impact of and offense and what could be done about it. Process: - Anyone affected by the event is invited to participate. - By the end of the circle, participants attempt to a reach consensus plan for the offender and a method to heal the victim and the community. Other practices - Community circles - Peer mediation - Conflict management - Comprehensive antibullying efforts - Affective curriculum development. | - Recommended to decrease discipline referrals and suspensions; while improving social and emotional skills of students such as empathy and conflict resolution. | D |

| Community-building circles plus restorative circles plus restorative conversations [37] | Aim: to create and maintain relationships and to heal the harm to those relationships when wrongdoing and conflict occur. Process: - Four-day restorative justice professional development training for teachers and staff. - The content includes restorative conversations, community-building circles, and restorative circles. No further details are provided. | - Their implementation along with restorative conversations is recommended in secondary education in order to improve relationships between students and teachers and academic outcomes. | D |

| Talking circles plus healing circles [38] | Talking circles Aims: to provide a significant basis for a restorative culture by letting teachers and students the same opportunity to express themselves and know their similarities and differences. Process: - Weekly program-wide talking circles. No further details are provided. Healing circles Aims: To solve conflicts. Elements: - A facilitator of the discussion. - The talking piece. An element that goes from participant to participant. Participants can speak only when they hold it. Process: - The harmed parties, and other members of the community conversate in a circle. - Three core: a) identify the harm; b) ask community members to say how they were impacted by it; and c) come up with ways for the responsible party to repair the harm. | - The implementation of weekly program-wide talking circles and smaller healing circles for conflicts is recommended in secondary education for students at-risk of dropping out school to develop and maintain relationships. | D |

| Preventive circles plus circles to intervene conflict [39] | Proactive circles Aims: to build character and foster positive attitudes. Process: - Daily circles for all grades for 30 min. - First opening question about a topic and students have the opportunity to respond. - Then, teachers facilitate a student discussion about the topic, prompting their opinions, feelings, and behaviors. Circles to intervene conflict Aims: to intervene conflicts. No further details are given on their elements and process. | Recommended as a schoolwide strategy for students from urban and low-income schools to improve social and emotional skills including communication, expression in terms of emotions and thoughts and perspective taking, as well as to improve learning. | D |

| Restorative conversations or discussions | |||

| Restorative conversations [40] | Aim: to address a problem while respecting each person’s dignity. Process: It focuses on engaging in conversations in which the emphasis is on the problem rather than the person. | - They are recommended in order to create a safe space for communication, develop problem-solving skills and increase motivation to attend school. | D |

| Specific models | |||

| The Fairness Committee Model [41] | Aims: to address community norms violations. Elements: - The committee hearing the cases including 1 or 2 students and 1 teacher, and 1 teacher facilitator. The committee is not fixed and is created for every case, drawing on the pool of the school community. Process: - It works as a gyratory reparative committee that involves all school community. - The committee search for suitable consequences for infractions by means of dialogue and consensus. - One participant may challenge another with his or her actions and explain how they have affected others. - The purpose is: a) resolve how to restore the community in the wake of actions incompatible with its values; and b) determine how to reintegrate the community sense. - Fairness remains open-ended and reliant upon the essentials of the event. | - It is recommended to encourage student voice, democratic participation and create a space of trust and confidence. It is recommended as well to validate students’ worth and humanity and prevent drop-out while allowing for academic re-socialization. | D |

| The restorative justice plan [42] | Aims: to educate students involved in hazing and achieve a commitment by school and community leaders that hazing would not be allowed. Educate students about the humiliating and potentially dangerous aspects of their behaviors. Elements: - Steps that should be taken in any restorative justice program (Zehr, 2002). - Best practices for developing a high school restorative justice program (Zaslaw, 2010). Process: - The restorative plan is presented to students. Failure to finish the plan would result in criminal charges being filed. - The plan requires offending students to participate in an educational program: (1) Students had a session with a nationally renowned facilitator to discuss the incident and hazing in general. (2) Development of a personal action plan that requires students to make presentations to high school students on the school disciplinary and the consequences of hazing. (3) Community service. Students are required to perform at least 20 h of community service to pay back the community for the use of taxpayer resources that had been expended due to the hazing. - On completion of the plan, all records of the incident are deleted. | - It is recommended for students in secondary education to decrease the frequency and severity of incidents of hazing and change the school culture of hazing. | D |

| The respect agreement and letter writing [43] | Respect agreement Aims: improve respect between members of a class-room. Process: At the beginning of the year students and teachers create it. They define collaboratively what is respect and exemplify how students can show respect to one another and their setting. Letter writing Aims: learn to apology and retribute between members of a class-room. Process: introduction of the practice by teachers as a way to apology and retribute. | - Recommended as a collaborative work between teachers and students in secondary education to develop actively listening and create an environment of shared respect and inclusion. - Recommended for students in secondary education to develop the competence of emotional regulation including the understanding of the relationship between emotion, thinking and behavior and acting consequently. | D |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mas-Expósito, L.; Krieger, V.; Amador-Campos, J.A.; Casañas, R.; Lalucat-Jo, L. Pocket Restorative Practice Approaches to Foster Peer-Based Relationships and Positive Development in Schools. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120880

Mas-Expósito L, Krieger V, Amador-Campos JA, Casañas R, Lalucat-Jo L. Pocket Restorative Practice Approaches to Foster Peer-Based Relationships and Positive Development in Schools. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):880. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120880

Chicago/Turabian StyleMas-Expósito, Laia, Virginia Krieger, Juan Antonio Amador-Campos, Rocío Casañas, and Lluís Lalucat-Jo. 2022. "Pocket Restorative Practice Approaches to Foster Peer-Based Relationships and Positive Development in Schools" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120880

APA StyleMas-Expósito, L., Krieger, V., Amador-Campos, J. A., Casañas, R., & Lalucat-Jo, L. (2022). Pocket Restorative Practice Approaches to Foster Peer-Based Relationships and Positive Development in Schools. Education Sciences, 12(12), 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120880