Interprofessional Education and Research in the Health Professions: A Systematic Review and Supplementary Topic Modeling

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search and Information Sources

[“health professions education”] AND [“interprofessional collaboration” OR “interprofessional teamwork” OR “multidisciplinary”] AND [“research”]

2.3. Initial Article Selection

3. Results

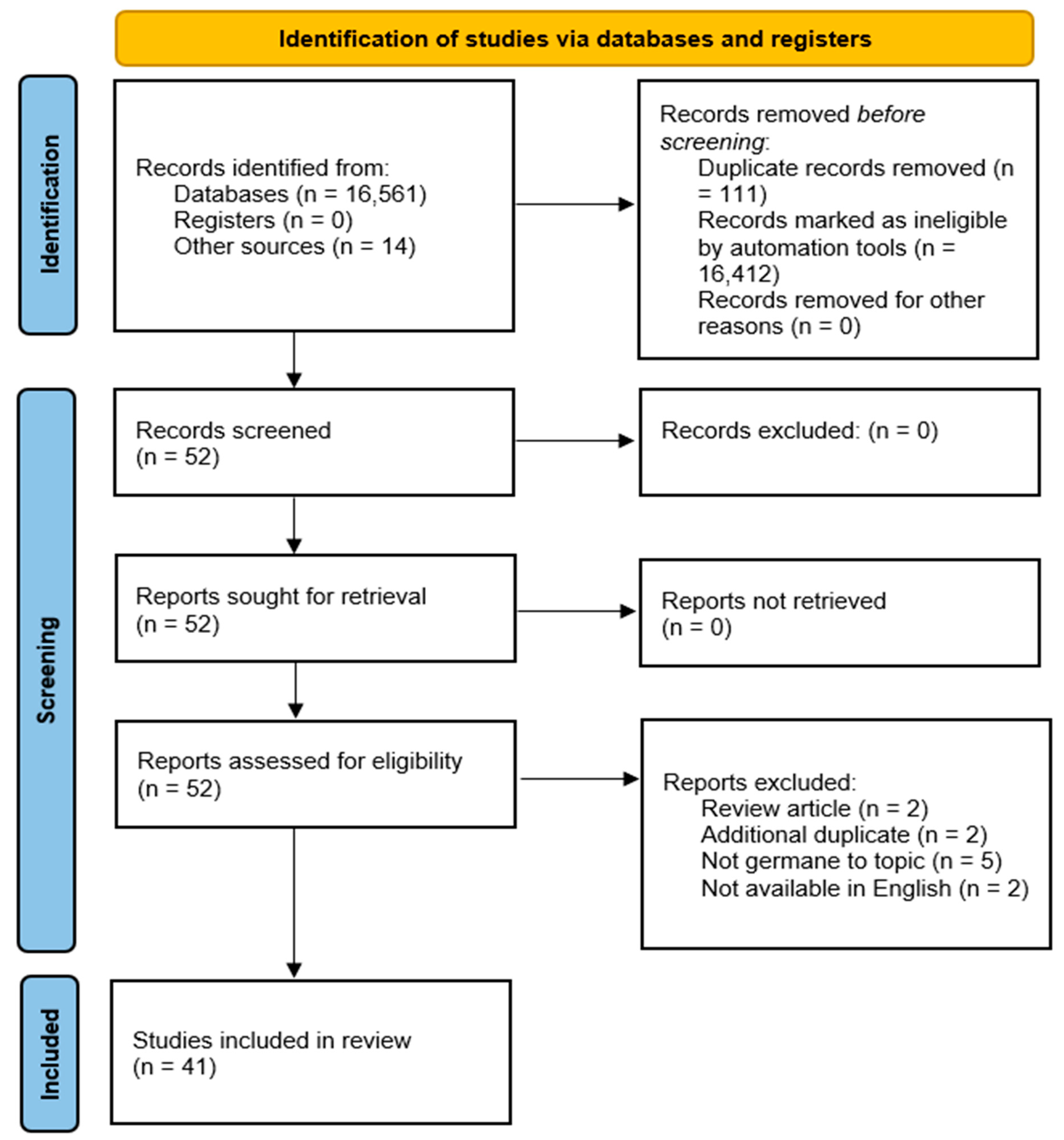

3.1. Study Selection

- Review articles (2 articles);

- Additional du-plicate articles (2 articles);

- Not germane to topic (5 articles);

- Not available in the English language (database selection error) (2 articles).

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Additional Analysis

3.4. Supplementary Analysis–Topic Modeling Validation

3.4.1. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) Method

3.4.2. Latent Dirichlet Allocation Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Provider IPE Perspective

4.2. Learner Perspective

4.3. Research IPE Perspective

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morano, C.; Damiani, G. Interprofessional education at the meso level: Taking the next step in IPE. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2019, 40, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Carroll, V.; Owens, M.; Sy, M.; El-Awaisi, A.; Xyrichis, A.; Leigh, J.; Nagraj, S.; Huber, M.; Hutchings, M.; McFadyen, A. Top tips for interprofessional education and collaborative practice research: A guide for students and early career researchers. J. Interprofessional Care 2021, 35, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baerg, K.; Lake, D.; Paslawski, T. Survey of Interprofessional Collaboration Learning Needs and Training Interest in Health Professionals, Teachers, and Students: An Exploratory Study. J. Res. Interprofessional Pract. Educ. 2012, 2, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.; Pulling, C.; McGraw, R.; Dagnone, J.D.; Hopkins-Rosseel, D.; Medves, J. Simulation in interprofessional education for patient-centred collaborative care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 64, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, V.O.; Cuzzola, R.; Knox, C.; Liotta, C.; Cornfield, C.S.; Tarkowski, R.D.; Masters, C.; McCarthy, M.; Sturdivant, S.; Carlson, J.N. Teamwork education improves trauma team performance in undergraduate health professional students. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2015, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, L.W.; Hassan, Z.; Shure, A.; Joshi, K.; Lillie, E.; Fung, K. Evaluating Attitudes Toward Interprofessional Collaboration and Education Among Health Professional Learners. Med. Sci. Educ. 2020, 30, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connaughton, J.; Edgar, S.; Waldron, H.; Adams, C.; Courtney, J.; Katavatis, M.; Ales, A. Health professional student attitudes towards teamwork, roles and values in interprofessional practice: The influence of an interprofessional activity. Focus Health Prof. Educ. (2204–7662) 2019, 20, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.B.; Singer, S.J.; Hayes, J.; Sales, M.; Vogt, J.W.; Raemer, D.; Meyer, G.S. Design and evaluation of simulation scenarios for a program introducing patient safety, teamwork, safety leadership, and simulation to healthcare leaders and managers. Simul. Healthc. 2011, 6, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Spencer-Dawe, E.; Mclean, E. Beginning the process of teamwork: Design, implementation and evaluation of an inter-professional education intervention for first year undergraduate students. J. Interprofessional Care 2005, 19, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, V.R.; Sharpe, D.; Flynn, K.; Button, P. A longitudinal study of the effect of an interprofessional education curriculum on student satisfaction and attitudes towards interprofessional teamwork and education. J. Interprofessional Care 2009, 24, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Motta, L.B.; Pacheco, L.C. Integrating Medical and Health Multiprofessional Residency Programs: The Experience in Building an Interprofessional Curriculum for Health Professionals in Brazil. Educ. Health Chang. Learn. Pract. 2014, 27, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Prospero, L.; Bhimji-Hewitt, S. Teaching Collaboration: A Retrospective Look at Incorporating Teamwork into an Interprofessional Curriculum. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2011, 42, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccott, L.; Greig, A.; Hall, W.; Lee, M.; Newton, C.; Wood, V. Evaluating students’ perceptions of an interprofessional problem-based pilot learning project. J. Allied Health 2012, 41, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Freeth, D.; Ayida, G.; Berridge, E.J.; Mackintosh, N.; Norris, B.; Sadler, C.; Strachan, A. Multidisciplinary Obstetric Simulated Emergency Scenarios (MOSES): Promoting Patient Safety in Obstetrics with Teamwork-Focused Interprofessional Simulations. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2009, 29, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogden, A.; Greenfield, D.; Nugus, P.; Kiernan, M.C. Engaging in patient decision-making in multidisciplinary care for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The views of health professionals. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2012, 6, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyun, J.; Kim, S.-J.; You, S.; Choi, H.; Sohn, S.; Bae, J.; Baik, M.; Cho, I.H.; Choi, K.-S.; Chung, C.-S.; et al. Psychosocial support during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea: Activities of multidisciplinary mental health professionals. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irajpour, A.; Alavi, M. Health professionals’ experiences and perceptions of challenges of interprofessional collaboration: Socio-cultural influences of IPC. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2015, 20, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Telles Jafelice, G.; Fernando Marcolan, J. Perception of Mental Health Professionals about the Multiprofessional Work with Residents. J. Nurs. UFPE/Rev. Enferm. UFPE 2017, 11, 542–550. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.; Jones, D. Improving teamwork, trust and safety: An ethnographic study of an interprofessional initiative. J. Interprofessional Care 2011, 25, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, P.; Pager, S.; Bell, K.; Hall, F.; Kendall, M. Do structured arrangements for multidisciplinary peer group supervision make a difference for allied health professional outcomes? J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2013, 2013, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kebe, N.N.M.K.; Chiocchio, F.; Bamvita, J.-M.; Fleury, M.-J. Profiling mental health professionals in relation to perceived interprofessional collaboration on teams. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lackie, K.; Miller, S.; Ayn, C.; Brown, M.; Helwig, M.; Houk, S.; Lane, J.; Mireault, A.; Neeb, D.; Picketts, L.; et al. Interprofessional collaboration between health professional learners when breaking bad news: A scoping review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2021, 19, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, J.; Broholm, M.; Rosenberg, J. Health professionals perceive teamwork with relatives as an obstacle in their daily work—A focus group interview. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2017, 31, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, E.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Widyandana, D.; Scherpbier, A. Understanding attitude of health care professional teachers toward interprofessional health care collaboration and education in a Southeast Asian country. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, A.P.; Roberts, S.; Baker, M.J.; Keijzers, G.; Young, J.; Stapelberg, N.J.C.; Crilly, J. Survey of research activity among multidisciplinary health professionals. Aust. Heal. Rev. 2016, 40, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nango, E.; Tanaka, Y. Problem-based learning in a multidisciplinary group enhances clinical decision making by medical students: A randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Dent. Sci. 2010, 57, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz de Morales-Romero, L.; Bermejo-Cantarero, A.; Martínez-Arce, A.; González-Pinilla, J.A.; Rodriguez-Guzman, J.; Baladrón-González, V.; Redondo-Sánchez, J.; Redondo-Calvo, F.J. Effectiveness of an Educational Intervention With High-Fidelity Clinical Simulation to Improve Attitudes Toward Teamwork Among Health Professionals. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2021, 52, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, H.; Samuelsson, M.; Ekdahl, S.; Halling, Y.; Öster, A.; Perseius, K.I. Experiences by patients and health professionals of a multidisciplinary intervention for long-term orofacial pain. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2013, 2013, 365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Okato, A.; Hashimoto, T.; Tanaka, M.; Tachibana, M.; Machizawa, A.; Okayama, J.; Endo, M.; Senda, M.; Saito, N.; Iyo, M. Hospital-based child protection teams that care for parents who abuse or neglect their children recognize the need for multidisciplinary collaborative practice involving perinatal care and mental health professionals: A questionnaire survey conducted in Japan. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Paans, W.; Wijkamp, I.; Wiltens, E.; Wolfensberger, M.V. What constitutes an excellent allied health care professional? A multidisciplinary focus group study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2013, 2013, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rainsford, S.; Hall Dykgraaf, S.; Kasim, R.; Phillips, C.; Glasgow, N. “Traversing difficult terrain”. Advance care planning in residential aged care through multidisciplinary case conferences: A qualitative interview study exploring the experiences of families, staff and health professionals. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K.; Zwarenstein, M.; Conn, L.G.; Kenaszchuk, C.; Russell, A.; Reeves, S. An intervention to improve interprofessional collaboration and communications: A comparative qualitative study. J. Interprofessional Care 2010, 24, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.; Kaplan, B.; Atallah, H.; Higgins, M.; Lewitt, M.J.; Ander, D.S. The Use of Simulation and a Modified TeamSTEPPS Curriculum for Medical and Nursing Student Team Training. Simul. Healthc. J. Soc. Simul. Healthc. 2010, 5, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosell, L.; Wihl, J.; Nilbert, M.; Malmström, M. Health Professionals’ Views on Key Enabling Factors and Barriers of National Multidisciplinary Team Meetings in Cancer Care: A Qualitative Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandahl, C.; Gustafsson, H.; Wallin, C.; Meurling, L.; Øvretveit, J.; Brommels, M.; Hansson, J. Simulation team training for improved teamwork in an intensive care unit. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2013, 26, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, Y.K.; Myers, J.; O’Connor, T.D.; Haskins, M. Interprofessional Simulation to Foster Collaboration between Nursing and Medical Students. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 9, e497–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, V.; Joubert, L.; Shlonsky, A.; Morris, A. Hospital Parenting Support for Adults with Incurable End-Stage Cancer: Multidisciplinary Health Professional Perspectives. Health Soc. Work. 2021, 46, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titzer, J.L.; Swenty, C.F.; Hoehn, W.G. An Interprofessional Simulation Promoting Collaboration and Problem Solving among Nursing and Allied Health Professional Students. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2012, 8, e325–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWielen, L.M.; Do, E.K.; Diallo, H.I.; LaCoe, K.N.; Nguyen, N.L.; Parikh, S.A.; Rho, H.Y.; Enurah, A.S.; Dumke, E.K.; Dow, A.W. Interprofessional Collaboration Led by Health Professional Students: A Case Study of the Inter Health Professionals Alliance at Virginia Commonwealth University. J. Res. Interprofessional Pract. Educ. 2014, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wakefield, A.; Cocksedge, S.; Boggis, C. Breaking bad news: Qualitative evaluation of an interprofessional learning opportunity. Med. Teach. 2006, 28, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, C.C.; Marent, B.; Dür, W.; Dorner, T.E. The struggle for inter-professional teamwork and collaboration in maternity care: Austrian health professionals’ perspectives on the implementation of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerace, A.; Curren, D.; Muir, C.E. Multidisciplinary health professionals’ assessments of risk: How are tools used to reach consensus about risk assessment and management? J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zaheer, S.; Ginsburg, L.R.; Wong, H.J.; Thomson, K.; Bain, L. Importance of safety climate, teamwork climate and demographics: Understanding nurses, allied health professionals and clerical staff perceptions of patient safety. BMJ Open Qual. 2018, 7, e000433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMaggio, P.; Nag, M.; Blei, D. Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of U.S. government arts funding. Poetics 2013, 41, 570–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Lowe, W. An automated information extraction tool for international conflict data with performance as good as human coders: A rare events evaluation design. Int. Organ. 2008, 57, 617–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinn, K.M.; Monroe, B.L.; Colaresi, M.; Crespin, M.H.; Radev, D.R. How to analyze political attention? Am. J. Political Sci. 2010, 54, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayansky, I.; Kumar, S.A.P. A review of topic modeling methods. Inf. Syst. 2020, 94, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, C.B.; Møller, C. Smart literature review: A practical topic modelling approach to exploratory literature review. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holder, A.K.; Karim, K.; Lin, J.; Woods, M. A content analysis of the comment letters to the FASB and IASB: Accounting for contingencies. Adv. Account. Inc. Adv. Int. Account. 2013, 29, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boritz, J.E.; Carnaghan, C.; Alencar, P.S. Business modeling to improve auditor risk assessment: An investigation of alternative representations. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 28, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, V.; Liu, Q.; Vasarhelyi, M.A. The development and intellectual structure of continuous auditing research. J. Account. Lit. 2014, 33, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Gerrish, S.; Wang, C.; Boydgraber, J.L.; Blei, D.M. Reading tea leaves: How humans interpret topic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2009, 21, 288–296. [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. What is Patient Experience? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/patient-experience/index.html (accessed on 12 November 2022).

| Article Assignment | Reviewer 1 | Reviewer 2 | Reviewer 3 | Reviewer 4 | Reviewer 5 | Reviewer 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | X | X | ||||

| 11–20 | X | X | ||||

| 21–30 | X | X | ||||

| 31–41 | X | X | X |

| Reference Number | Author(s)/Year | Article Title | Journal/Publication | Learners | Article Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | Baerg et al., 2012 | Survey of Interprofessional Collaboration Learning Needs and Training Interest in Health Professionals, Teachers, and Students: An Exploratory Study | Journal of Researching Interprofessional Practice and Education | Practicing professionals and students from the sectors of health and education | Survey with descriptive analysis |

| [4] | Baker et al., 2008 | Simulation in interprofessional education for patient-centered collaborative care | Journal of Advanced Nursing | 101 nursing students, 42 medical students and 70 junior medical residents | Action research approach |

| [5] | Baker et al., 2015 | Teamwork education improves trauma team performance in undergraduate health professional students | Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professionals | Teams of undergraduate health professional students from four programs: nursing, physician assistant, radiologic science, and respiratory care | Pre- and post-test analysis |

| [6] | Christian et al., 2020 | Evaluating Attitudes Toward Interprofessional Collaboration and Education Among Health Professional Learners | Medical Science Educator | Pharmacy, optometry nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, social work working professionals | Quantitative pre-post analysis on learning attitudes following a workshop |

| [7] | Connaughton et al., 2019 | Health professional student attitudes towards teamwork, roles and values in interprofessional practice: The influence of an interprofessional activity | Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-Professional Journal | Medical, physiotherapy, and nursing students | Quantitative pre- and post-surveys conducted using the Interprofessional Attitude’s Scale (IPAS) |

| [8] | Cooper et al., 2011 | Design and evaluation of simulation scenarios for a program introducing patient safety, teamwork, safety leadership, and simulation to healthcare leaders and managers | Simul Healthcare | Individual participants who attended simulation training focused on teamwork and safety leadership | Mixed Methods: Thematic analysis of Qualitative data |

| [9] | Cooper et al., 2005 | Design, implementation and evaluation of an inter-professional education intervention for first year undergraduate students | Journal of Interprofessional Care | First year undergraduate students studying medicine, nursing, physiotherapy and occupational therapy | Evidence-based interprofessional educational (IPE) intervention |

| [10] | Curran et al., 2010 | A longitudinal study of the effect of an interprofessional education curriculum on student satisfaction and attitudes towards interprofessional teamwork and education | Journal of Interprofessional Care | Health and human service professional students | Time series study design |

| [11] | da Motta & Pacheco, 2014 | Integrating Medical and Health Multiprofessional Residency Programs: The Experience in Building an Interprofessional Curriculum for Health Professionals in Brazil | Education for Health | Medicine, nursing, nutrition, psychology, physiotherapy, and social service residency students | Descriptive analysis of program interprofessional characteristics |

| [12] | Di Prospero & Bhimji-Hewitt, 2011 | Teaching collaboration: A retrospective look at incorporating teamwork into an interprofessional curriculum | Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences | Interprofessional education (IPE) curriculum has been integrated health professional programs | Retrospective collaborative inquiry |

| [13] | Eccott et al., 2012 | Evaluating students’ perceptions of an interprofessional problem based pilot learning project | Journal of Allied Health | Convenience sample of 24 students from medicine, pharmacy, nursing, physical therapy, and occupational therapy | Pre-post mixed-methods |

| [14] | Freeth et al., 2009 | Multidisciplinary obstetric simulated emergency scenarios (MOSES): Promoting patient safety in obstetrics with teamwork-focused interprofessional simulations | Journal of Continuing Education for Health Professions | Midwives, obstetricians and anesthetists | Mixed Methods: Thematic analysis of Qualitative data |

| [15] | Greenfield & Kiernan, 2012 | Engaging in patient decision-making in multidisciplinary care for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the views of health professionals | Patient Preference and Adherence | Medical providers participating in patient decision-making in multidisciplinary care for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | Individual and group interviews |

| [16] | Hyun et al., 2020 | Psychosocial support during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea: Activities of multidisciplinary mental health professionals | Journal Korean Medical Science | Multidisciplinary team of mental health professionals | Case study/report of mental health processes and outcomes |

| [17] | Irajpour & Alavi, 2014 | Health professionals’ experiences and perceptions of challenges of interprofessional collaboration: Socio-cultural influences of IPC | Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research | Samples of HPs from various disciplines including nurses, medical doctors (MDs) from variety of specialties, social workers, and psychologists from health system in Iran and Germany | Pilot qualitative descriptive study |

| [18] | Jafelice & Marcolan, 2017 | Perception of Mental Health Professionals About the Multiprofessional Work with Residents | Journal of Nursing UFPE On Line | Recently graduate mental health professionals | Exploratory descriptive study with a qualitative approach |

| [19] | Jones & Jones, 2011 | Improving teamwork, trust and safety: An ethnographic study of an interprofessional initiative | Journal of Interprofessional Care | No specific number identified in paper. Participants selected from approximately 250 staff | Ethnography |

| [20] | Kebe et al., 2019 | Profiling mental health professionals in relation to perceived interprofessional collaboration on teams | SAGE Open Medicine | Mental health professionals working in primary care and specialized mental health local service networks | Cluster analysis |

| [21] | Kuipers et al., 2013 | Do structured arrangements for multidisciplinary peer group supervision make a difference for allied health professional outcomes? | Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare | Allied health professions participating in peer group supervision activities | Descriptive analysis |

| [22] | Lackie et al., 2021 | Interprofessional collaboration between health professional learners when breaking bad news: a scoping review protocol | JBI Evidence Synthesis | Studies included involved health care professional curriculum focusing on how to teach the delivery of bad news to stakeholders | Review protocol |

| [23] | Laursen et al., 2017 | Health professionals perceive teamwork with relatives as an obstacle in their daily work - a focus group interview | Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences | Healthcare providers in the outpatient/clinic setting | Focus group interview |

| [24] | Lestari et al., 2018 | Understanding attitude of health care professional teachers toward interprofessional health care collaboration and education in a Southeast Asian country | Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare | Medicine, nursing, midwifery, and dentistry faculty members at 17 institutions | Qualitative/explanatory, sequential mixed-methods design |

| [25] | Marshall et al., 2016 | Survey of research activity among multidisciplinary health professionals | Australian Health Review | Health service employees | Mixed methods study using a cross-sectional online survey and interviews |

| [26] | Morales-Romero et al., 2021 | Effectiveness of an Educational Intervention with High-Fidelity Clinical Simulation to Improve Attitudes Toward Teamwork Among Health Professionals | The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing | Interprofessional group of health professionals | quasi-experimental study with an educational intervention |

| [27] | Nango & Tanaka, 2010 | Problem-based learning in a multidisciplinary group enhances clinical decision making by medical students: A randomized controlled trial | Journal of Medical and Dental Sciences | Medical students | Randomized controlled trial |

| [28] | Nilsson et al., 2013 | Experiences by patients and health professionals of a multidisciplinary intervention for long-term orofacial pain | Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare | Patients and multidisciplinary health professionals associated with long-term orofacial pain | Group interview, qualitative content analysis |

| [29] | Okato et al., 2018 | Hospital-based child protection teams that care for parents who abuse or neglect their children recognize the need for multidisciplinary collaborative practice involving perinatal care and mental health professionals: a questionnaire survey conducted in Japan | Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare | Members of a hospital-based child protection team | Exploratory factor analysis, correlation analysis |

| [30] | Paans et al., 2013 | What constitutes an excellent allied health care professional? A multidisciplinary focus group study | Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare | Allied health care professionals | Focus group discussions and a Delphi panel survey analysis |

| [31] | Rainsford et al., 2021 | ‘Traversing difficult terrain’. Advance care planning in residential aged care through multidisciplinary case conferences: A qualitative interview study exploring the experiences of families, staff and health professionals | Palliative Medicine | Medical providers, staff, and patients/family | Qualitative study with semi-structured interviews |

| [32] | Rice et al., 2010 | An intervention to improve interprofessional collaboration and communications: a comparative qualitative study | Journal of Interprofessional Care | 12 health professionals in a rehabilitation ward | Ethnography |

| [33] | Robertson et al., 2010 | The use of simulation and a modified TeamSTEPPS curriculum for medical and nursing student team training | Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare | Two hundred thirteen students participated in a 4-h team training program | Pre-post mixed-methods |

| [34] | Rosell et al., 2020 | Health Professionals’ Views on Key Enabling Factors and Barriers of National Multidisciplinary Team Meetings in Cancer Care: A Qualitative Study | Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare | Multidisciplinary health professionals involved in the treatment of specific types of cancers | Conventional content analysis |

| [35] | Sandahl et al., 2013 | Simulation team training for improved teamwork in an intensive care unit | International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance | 152 ICU staff consisting of medical staff and nurses | Action Research |

| [36] | Scherer et al., 2013 | Interprofessional simulation to foster collaboration between nursing and medical students | Clinical Simulation in Nursing | Nursing and medical students | Quasi-experimental pilot study using a prepost test design |

| [37] | Steiner et al., 2021 | Hospital Parenting Support for Adults with Incurable End-Stage Cancer: Multidisciplinary Health Professional Perspectives | Health & Social Work | 12 multidisciplinary healthcare providers | Exploratory study |

| [38] | Titzer et al., 2012 | An Interprofessional Simulation Promoting Collaboration and Problem Solving among Nursing and Allied Health Professional Students | Clinical Simulation in Nursing | Interprofessional simulation involving nursing, radiologic technology, respiratory, and occupational therapy students | Post training/simulation debriefing |

| [39] | VanderWielen et al., 2014 | Interprofessional Collaboration Led by Health Professional Students: A Case Study of the Inter Health Professionals Alliance at Virginia Commonwealth University | Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education | Students at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) student healthcare organization/members | Qualitative post-IPE survey for student participants |

| [40] | Wakefield et al., 2006 | Breaking bad news: Qualitative evaluation of an interprofessional learning opportunity | Medical Teacher | Nursing and medical students | Mixed method |

| [41] | Wieczorek et al., 2016 | The struggle for inter-professional teamwork and collaboration in maternity care: Austrian health professionals’ perspectives on the implementation of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative | BMC Health Services Research | Multidisciplinary (physicians, midwives, and nurses) involved in hospital maternity care | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews conducted |

| [42] | Winship, 2013 | Multidisciplinary health professionals’ assessments of risk: how are tools used to reach consensus about risk assessment and management? | Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing | All health professionals in an acute care and community psychiatric service for elderly patients | Semi-structured interviews |

| [43] | Zaheer et al., 2018 | Importance of safety climate, teamwork climate and demographics: understanding nurses, allied health professionals and clerical staff perceptions of patient safety | BMJ Open Quality | Nursing and allied health professionals and unit clerks working in intensive care, general medicine, mental health, and/or the emergency department | Cross-sectional survey analysis |

| Topic | Proportion |

|---|---|

| Medical/clinical skills for patients | 33.00% |

| Group training and collaboration | 25.80% |

| Training/practice on patients | 14.80% |

| Research support | 13.30% |

| Simulation and learning | 13.10% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lieneck, C.; Wang, T.; Gibbs, D.; Russian, C.; Ramamonjiarivelo, Z.; Ari, A. Interprofessional Education and Research in the Health Professions: A Systematic Review and Supplementary Topic Modeling. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120850

Lieneck C, Wang T, Gibbs D, Russian C, Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Ari A. Interprofessional Education and Research in the Health Professions: A Systematic Review and Supplementary Topic Modeling. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):850. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120850

Chicago/Turabian StyleLieneck, Cristian, Tiankai Wang, David Gibbs, Chris Russian, Zo Ramamonjiarivelo, and Arzu Ari. 2022. "Interprofessional Education and Research in the Health Professions: A Systematic Review and Supplementary Topic Modeling" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120850

APA StyleLieneck, C., Wang, T., Gibbs, D., Russian, C., Ramamonjiarivelo, Z., & Ari, A. (2022). Interprofessional Education and Research in the Health Professions: A Systematic Review and Supplementary Topic Modeling. Education Sciences, 12(12), 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120850