A Systematic Review of the Validity of Questionnaires in Second Language Research

Abstract

1. A Systematic Review of the Validity of Questionnaires in Second Language Research

2. Conceptual Framework: The Argument-Based Approach to Validity

3. The Present Study

- What are the characteristics of the questionnaires used in L2 research in terms of the number and types of items, research design, research participants, and study context?

- What validity inferences drawn from the questionnaire data were justified, what methods were employed to investigate the plausibility of each inference, and what evidence/backing was collected to support each inference?

4. Method

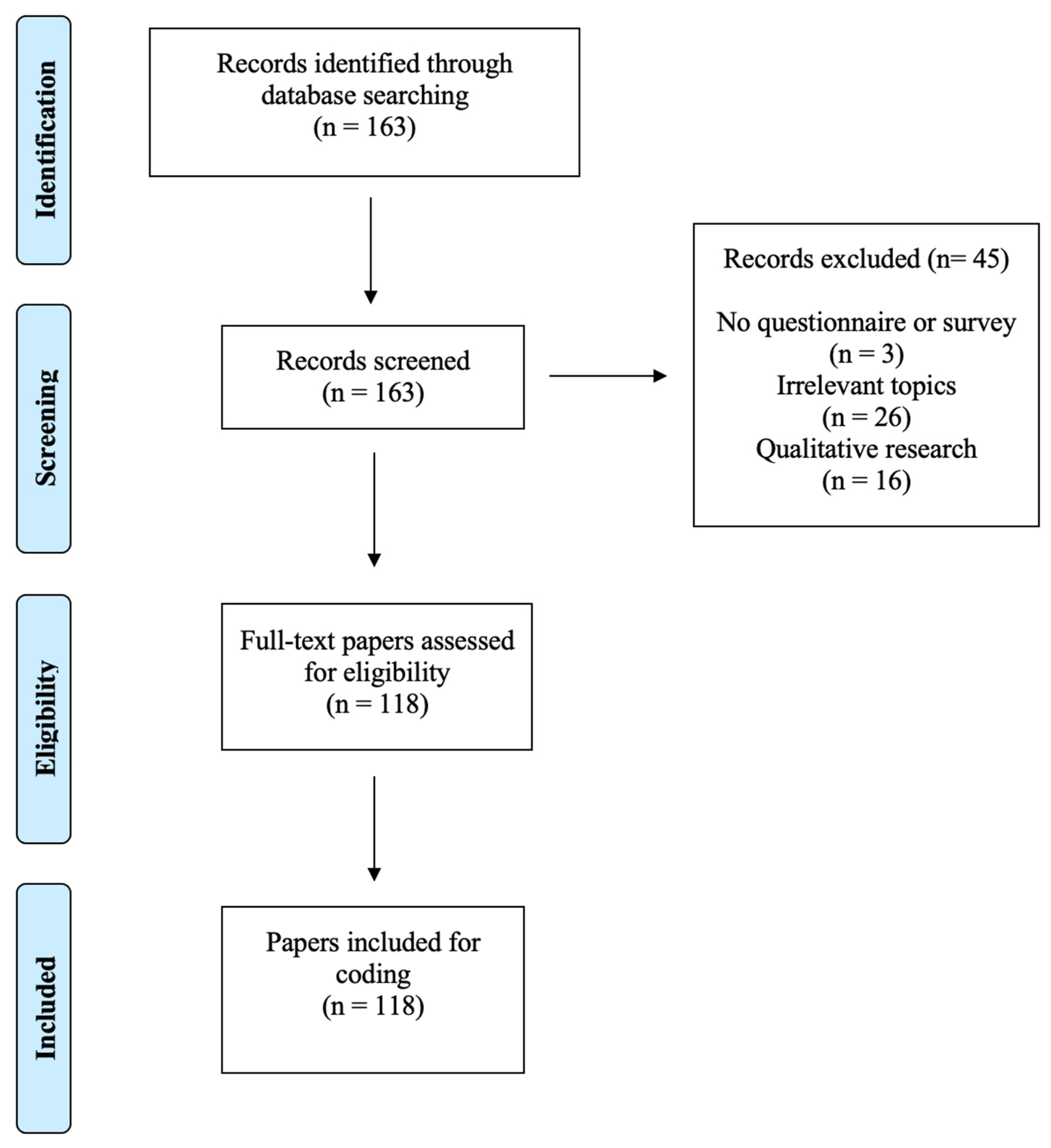

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Coding Scheme

5. Results

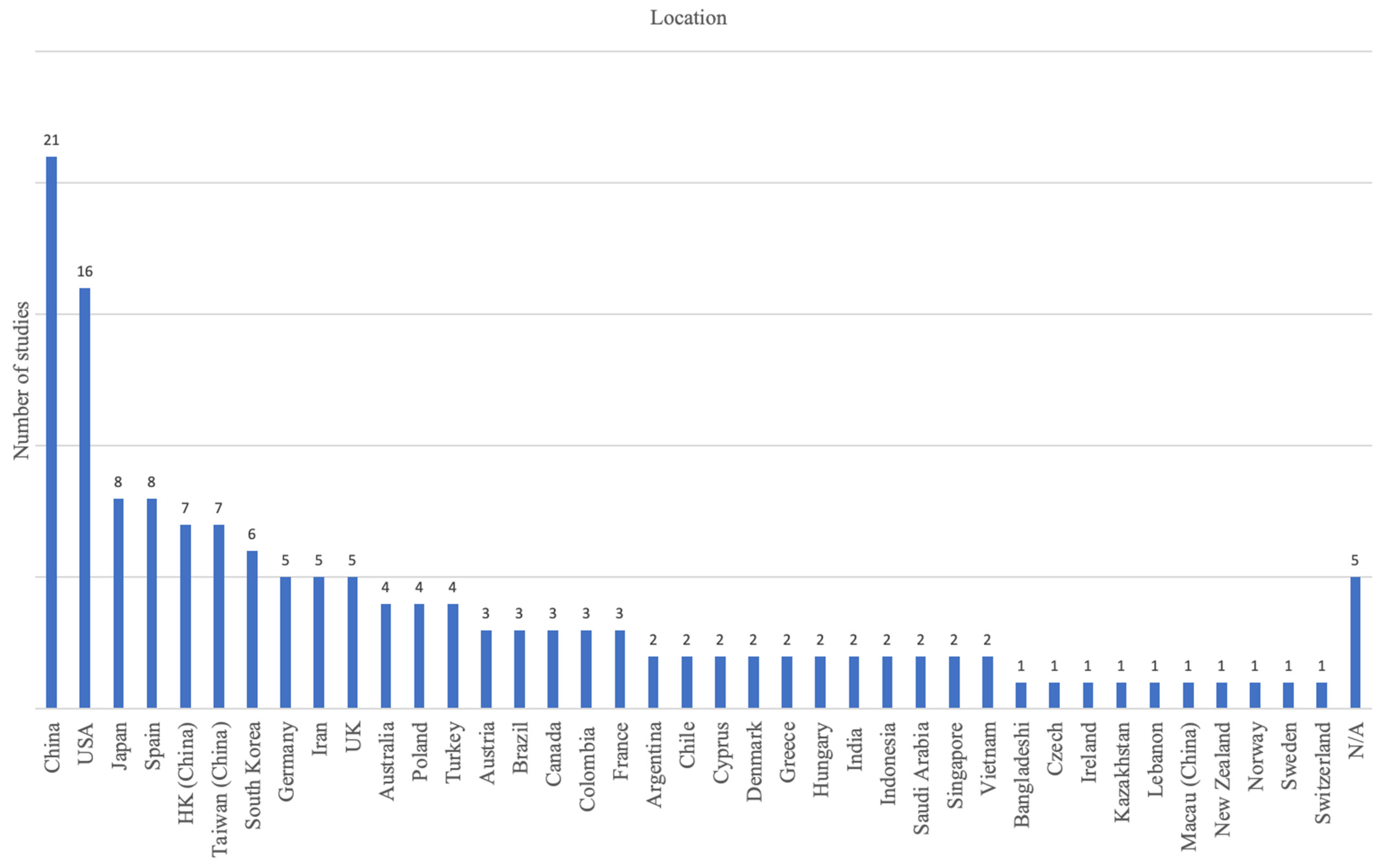

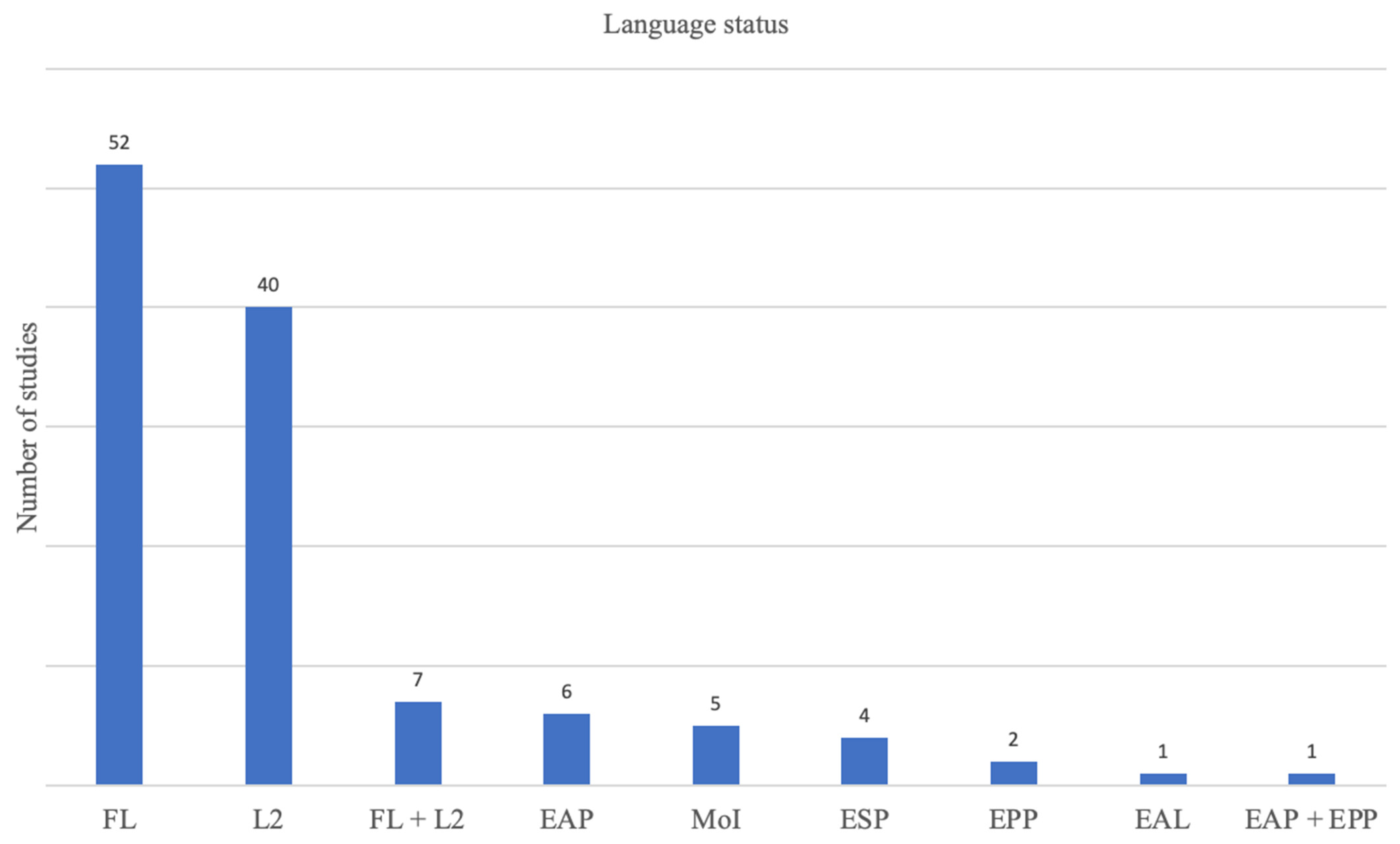

5.1. Characteristics of the Questionnaires

5.2. Methods Used to Provide Validity Evidence for the Questionnaires

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Question One: The Characteristics of the Questionnaires

6.2. Research Question Two: Validity Evidence

6.2.1. The Domain Description Inference

6.2.2. The Evaluation Inference

6.2.3. The Generalization Inference

6.2.4. The Explanation Inference

6.3. Implications of the Study

6.4. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Journal | |

| 1 | Annual Review of Applied Linguistics |

| 2 | Applied Linguistics |

| 3 | Applied Linguistics Review |

| 4 | Assessing Writing |

| 5 | Computer Assisted Language Learning |

| 6 | English for Specific Purposes |

| 7 | Foreign Language Annals |

| 8 | International Multilingual Research Journal |

| 9 | Journal of English for Academic Purposes |

| 10 | Journal of Second Language Writing |

| 11 | Language and Education |

| 12 | Language Assessment Quarterly |

| 13 | Language Learning |

| 14 | Language Learning & Technology |

| 15 | Language Learning and Development |

| 16 | Language Teaching |

| 17 | Language Teaching Research |

| 18 | Language Testing |

| 19 | ReCALL |

| 20 | Second Language Research |

| 21 | Studies in Second Language Acquisition |

| 22 | System |

| 23 | TESOL Quarterly |

| 24 | The Modern Language Journal |

Appendix B

Variables and Definitions in the Coding Scheme

| Variables | Description | References |

| 1. Bibliographical information | ||

| Authors | Researchers who conducted the study | |

| Article title | The title of the paper | |

| Journal | The journal in which the study was published | |

| 2. Basic information about the questionnaires | ||

| Number of questionnaire items | The number of items in the questionnaires | |

| Type of questionnaire items | Closed-ended | [1] |

| Open-ended | ||

| Mixed-type | ||

| Source of questionnaire | Developed by the researchers themselvesAdopted from previous research | |

| 3. Research design | ||

| Quantitative: data are numerical; statistical analyses are used to address research questions. | [44] | |

| Mixed: a combination of quantitative and qualitative data | ||

| 4. Study context | ||

| Location of the study | The country or region where the study was conducted. | [42] |

| Target language | The language that was investigated in the study. | |

| Language status | ||

| EAL: English as an additional language | ||

| EAP: English for academic purposes | ||

| EPP: English for professional purposes | ||

| ESP: English for specific purposes | ||

| FL: Foreign language | ||

| L2: Second language | ||

| MoI: Medium of instruction | ||

| 5. Participant information | ||

| Participant status | ||

| Learner | [42] | |

| Teacher | ||

| Pre-service teacher | ||

| Foreign or second language user | ||

| Linguistic layperson | ||

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | ||

| Secondary | ||

| Tertiary | ||

| Language institute | ||

| Pesantren school | ||

| Sample size | ||

| The number of participants who responded to the questionnaire | ||

| 6. Validity evidence | ||

| Domain description | ||

| What the questionnaire claims to measure, which can be classified into three types of information: | [1,19,21] | |

| Factual | ||

| Behavioral | ||

| Attitudinal | ||

| Evaluation | ||

| Scaling instrument employed by the questionnaire, such as | [19,21] | |

| Likert scale | ||

| Multiple choice | ||

| Frequency count | ||

| Mixed | ||

| Generalization | ||

| Reliability estimates (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha and Rasch item reliability) G theory analysis | [14,19,21] | |

| Explanation | ||

| Dimensionality analysis through using Rasch measurement | Authors (XXXXa); [19,21,26] | |

| Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) | ||

| Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) | ||

| Principle component analysis (PCA) | ||

Appendix C

Basic Information about the Questionnaires

| # of Studies | % | |

| Number of questionnaire item | ||

| >100 | 3 | 2.54 |

| 50–100 | 19 | 16.10 |

| <50 | 86 | 72.88 |

| N/A | 10 | 8.47 |

| Type of questionnaire item | ||

| Closed-ended | 72 | 61.02 |

| Mixed-type | 45 | 38.14 |

| Open-ended | 1 | 0.85 |

| Source of the questionnaires | ||

| Developed by the researchers themselves | 40 | 33.90 |

| Adopted from previous research | 78 | 66.10 |

Appendix D

Research Design of the Studies Published in Each Journal

| Journal | Quantitative Research Design | Mixed Research Design | Total | ||

| # of Studies | % | # of Studies | % | # of Studies | |

| Language Teaching Research | 10 | 40.00 | 15 | 60.00 | 25 |

| Computer Assisted Language Learning | 7 | 29.17 | 17 | 70.83 | 24 |

| System | 10 | 55.56 | 8 | 44.44 | 18 |

| Foreign Language Annals | 3 | 33.33 | 6 | 66.67 | 9 |

| Journal of English for Academic Purposes | 2 | 28.57 | 5 | 71.43 | 7 |

| The Modern Language Journal | 2 | 40.00 | 3 | 60.00 | 5 |

| Language Assessment Quarterly | 1 | 25.00 | 3 | 75.00 | 4 |

| RECALL | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 100.00 | 4 |

| Applied Linguistics Review | 1 | 33.33 | 2 | 66.67 | 3 |

| Assessing Writing | 1 | 33.33 | 2 | 66.67 | 3 |

| English for Specific Purposes | 1 | 33.33 | 2 | 66.67 | 3 |

| Language Learning and Technology | 1 | 33.33 | 2 | 66.67 | 3 |

| Language Testing | 3 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 |

| Journal of Second Language Writing | 1 | 50.00 | 1 | 50.00 | 2 |

| Studies in Second Language Acquisition | 2 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 |

| TESOL Quarterly | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 100.00 | 2 |

| Language Learning | 1 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 |

Appendix E

Participant Information

| # of Studies | % | |

| Participant status | ||

| Learner | 88 | 74.58 |

| Teacher | 11 | 9.32 |

| Pre-service teacher | 8 | 6.78 |

| Learner + Teacher | 7 | 5.93 |

| Linguistic layperson | 2 | 1.69 |

| Learner + Alumni | 1 | 0.85 |

| EFL users in the workplace | 1 | 0.85 |

| Educational level | ||

| Tertiary | 80 | 67.80 |

| Secondary | 17 | 14.41 |

| Primary | 8 | 6.78 |

| Language institute | 4 | 3.39 |

| Primary + Secondary | 2 | 1.69 |

| Secondary + Tertiary | 1 | 0.85 |

| Primary + Secondary + Tertiary + Community centers | 1 | 0.85 |

| Pesantren school | 1 | 0.85 |

| N/A | 4 | 3.39 |

| Sample size | ||

| <30 | 16 | 13.56 |

| Between 30–100 | 41 | 34.75 |

| Between 101–500 | 48 | 40.68 |

| Between 501–1000 | 8 | 6.78 |

| >1000 | 5 | 4.24 |

| Note: “+” means a combination of participant status or educational level. | ||

Appendix F

Excluded Papers with Irrelevant Topics

| 1 | Commitment to the profession of ELT and an organization: A profile of expat faculty in South Korea |

| 2 | Emotion recognition ability across different modalities: The role of language status (L1/LX), proficiency and cultural background |

| 3 | Towards growth for Spanish heritage programs in the United States: Key markers of success |

| 4 | Single author self-reference: Identity construction and pragmatic competence |

| 5 | Immigrant minority language maintenance in Europe: focusing on language education policy and teacher-training |

| 6 | A periphery inside a semi-periphery: The uneven participation of Brazilian scholars in the international community |

| 7 | Interrelationships of motivation, self-efficacy and self-regulatory strategy use: An investigation into study abroad experiences |

| 8 | Inhibitory Control Skills and Language Acquisition in Toddlers and Preschool Children |

| 9 | Le francais non-binaire: Linguistic forms used by non-binary speakers of French |

| 10 | After Study Abroad: The Maintenance of Multilingual Identity Among Anglophone Languages Graduates |

| 11 | Each primary school a school-based language policy? The impact of the school context on policy implementation |

| 12 | Multilingualism and Mobility as Collateral Results of Hegemonic Language Policy |

| 13 | A quantitative approach to heritage language use and symbolic transnationalism. Evidence from the Cuban-American population in Miami |

| 14 | Examining K-12 educators’ perception and instruction of online accessibility features |

| 15 | Red is the colour of the heart’: making young children’s multilingualism visible through language portraits |

| 16 | Active bi- and trilingualism and its influencing factors |

| 17 | Enhancing multimodal literacy using augmented reality |

| 18 | Developing multilingual practices in early childhood education through professional development in Luxembourg |

| 19 | Teaching languages online: Professional vision in the making |

| 20 | The provision of student support on English Medium Instruction programmes in Japan and China |

| 21 | Profesores Adelante! Recruiting teachers in the target language |

| 22 | Engaging expectations: Measuring helpfulness as an alternative to student evaluations of teaching |

| 23 | Can engaging L2 teachers as material designers contribute to their professional development? findings from Colombia |

| 24 | Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions |

| 25 | Understanding language teacher wellbeing: An ESM study of daily stressors and uplifts |

| 26 | Studying Chinese language in higher education: The translanguaging reality through learners’ eyes |

Appendix G

Included Papers

| Citation | |

| 1 | Teng, L. S., Yuan, R. E., & Sun, P. P. (2020). A mixed-methods approach to investigating motivational regulation strategies and writing proficiency in English as a foreign language contexts. System, 88, 102182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102182 |

| 2 | Peng, H., Jager, S., & Lowie, W. (2020). A person-centred approach to L2 learners’ informal mobile language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1868532 |

| 3 | Jamil, M. G. (2020). Academic English education through research-informed teaching: Capturing perceptions of Bangladeshi university students and faculty members. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820943817. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820943817 |

| 4 | Cañado, M. L. P. (2020). Addressing the research gap in teacher training for EMI: An evidence-based teacher education proposal in monolingual contexts. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 48, 100927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100927 |

| 5 | Carhill-Poza, A., & Chen, J. (2020). Adolescent English learners’ language development in technology-enhanced classrooms. Language Learning & Technology, 24(3), 52–69. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44738 |

| 6 | Chauvin, R., Fenouillet, F., & Brewer, S. S. (2020). An investigation of the structure and role of English as a Foreign Language self-efficacy beliefs in the workplace. System, 91, 102251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102251 |

| 7 | Huang, Becky H., Alison L. Bailey, Daniel A. Sass, and Yung-hsiang Shawn Chang. “An investigation of the validity of a speaking assessment for adolescent English language learners.” Language Testing 38, no. 3 (2021): 401–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532220925731 |

| 8 | Law, L., & Fong, N. (2020). Applying partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in an investigation of undergraduate students’ learning transfer of academic English. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 46, 100884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100884 |

| 9 | Tsang, A. (2020). Are learners ready for Englishes in the EFL classroom? A large-scale survey of learners’ views of non-standard accents and teachers’ accents. System, 94, 102298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102298 |

| 10 | Wang, L., & Fan, J. (2020). Assessing Business English writing: The development and validation of a proficiency scale. Assessing Writing, 46, 100490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100490 |

| 11 | Wei, X., Zhang, L. J., & Zhang, W. (2020). Associations of L1-to-L2 rhetorical transfer with L2 writers’ perception of L2 writing difficulty and L2 writing proficiency. Journal of English for academic purposes, 47, 100907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100907 |

| 12 | Wach, A., & Monroy, F. (2020). Beliefs about L1 use in teaching English: A comparative study of Polish and Spanish teacher-trainees. Language teaching research, 24(6), 855–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168819830422 |

| 13 | Aizawa, I., Rose, H., Thompson, G., & Curle, S. (2020). Beyond the threshold: Exploring English language proficiency, linguistic challenges, and academic language skills of Japanese students in an English medium instruction programme. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820965510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820965510 |

| 14 | Tsai, S. C. (2020). Chinese students’ perceptions of using Google Translate as a translingual CALL tool in EFL writing. Computer assisted language learning, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1799412 |

| 15 | Ghaffar, M. A., Khairallah, M., & Salloum, S. (2020). Co-constructed rubrics and assessment for learning: The impact on middle school students’ attitudes and writing skills. Assessing Writing, 45, 100468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100468 |

| 16 | Zhao, H., & Zhao, B. (2020). Co-constructing the assessment criteria for EFL writing by instructors and students: A participative approach to constructively aligning the CEFR, curricula, teaching and learning. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820948458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820948458 |

| 17 | Sun, T., & Wang, C. (2020). College students’ writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulated learning strategies in learning English as a foreign language. System, 90, 102221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102221 |

| 18 | Kim, Y., Choi, B., Kang, S., Kim, B., & Yun, H. (2020). Comparing the effects of direct and indirect synchronous written corrective feedback: Learning outcomes and students’ perceptions. Foreign Language Annals, 53(1), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12443 |

| 19 | Bai, B., & Wang, J. (2020). Conceptualizing self-regulated reading-to-write in ESL/EFL writing and investigating its relationships to motivation and writing competence. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820971740. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820971740 |

| 20 | Sato, M., & Storch, N. (2020). Context matters: Learner beliefs and interactional behaviors in an EFL vs. ESL context. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820923582. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820923582 |

| 21 | Quan, T. (2020). Critical language awareness and L2 learners of Spanish: An action-research study. Foreign Language Annals, 53(4), 897–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12497 |

| 22 | Alsuhaibani, Z. (2020). Developing EFL students’ pragmatic competence: The case of compliment responses. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820913539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820913539 |

| 23 | Yüksel, H. G., Mercanoğlu, H. G., & Yılmaz, M. B. (2020). Digital flashcards vs. wordlists for learning technical vocabulary. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1854312 |

| 24 | Dashtestani, R., & Hojatpanah, S. (2020). Digital literacy of EFL students in a junior high school in Iran: voices of teachers, students and Ministry Directors. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1744664 |

| 25 | Sun, X., & Hu, G. (2020). Direct and indirect data-driven learning: An experimental study of hedging in an EFL writing class. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820954459. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820954459 |

| 26 | Smith, S. (2020). DIY corpora for Accounting & Finance vocabulary learning. English for Specific Purposes, 57, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.08.002 |

| 27 | Shi, B., Huang, L., & Lu, X. (2020). Effect of prompt type on test-takers’ writing performance and writing strategy use in the continuation task. Language Testing, 37(3), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532220911626 |

| 28 | Wong, Y. K. (2020). Effects of language proficiency on L2 motivational selves: A study of young Chinese language learners. System, 88, 102181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102181 |

| 29 | Yoshida, R. (2020). Emotional scaffolding in text chats between Japanese language learners and native Japanese speakers. Foreign Language Annals, 53(3), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12477 |

| 30 | Miller, Z. F., & Godfroid, A. (2020). Emotions in incidental language learning: An individual differences approach. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(1), 115–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226311900041X |

| 31 | Teng, L. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2020). Empowering learners in the second/foreign language classroom: Can self-regulated learning strategies-based writing instruction make a difference?. Journal of Second Language Writing, 48, 100701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2019.100701 |

| 32 | Arnó-Macià, E., Aguilar-Pérez, M., & Tatzl, D. (2020). Engineering students' perceptions of the role of ESP courses in internationalized universities. English for Specific Purposes, 58, 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.12.001 |

| 33 | Farid, A., & Lamb, M. (2020). English for Da'wah? L2 motivation in Indonesian pesantren schools. System, 94, 102310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102310 |

| 34 | Yu, J., & Geng, J. (2020). English language learners’ motivations and self-identities: A structural equation modelling analysis of survey data from Chinese learners of English. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(4), 727–755. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0047 |

| 35 | Dimova, S. (2020). English language requirements for enrolment in EMI programs in higher education: A European case. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 47, 100896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100896 |

| 36 | Fenyvesi, K. (2020). English learning motivation of young learners in Danish primary schools. Language Teaching Research, 24(5), 690–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818804835 |

| 37 | Wang, Y., Grant, S., & Grist, M. (2021). Enhancing the learning of multi-level undergraduate Chinese language with a 3D immersive experience-An exploratory study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(1–2), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1774614 |

| 38 | Ma, Q. (2020). Examining the role of inter-group peer online feedback on wiki writing in an EAP context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(3), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1556703 |

| 39 | Ahmadian, M. J. (2020). Explicit and implicit instruction of refusal strategies: Does working memory capacity play a role?. Language Teaching Research, 24(2), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818783215 |

| 40 | Zhang, R. (2020). Exploring blended learning experiences through the community of inquiry framework. Language Learning & Technology, 24(1), 38–53. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44707 |

| 41 | Banister, C. (2020). Exploring peer feedback processes and peer feedback meta-dialogues with learners of academic and business English. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820952222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820952222 |

| 42 | Fan, Y., & Xu, J. (2020). Exploring student engagement with peer feedback on L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 50, 100775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2020.100775 |

| 43 | Bobkina, J., & Domínguez Romero, E. (2020). Exploring the perceived benefits of self-produced videos for developing oracy skills in digital media environments. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1802294 |

| 44 | Hu, X., & McGeown, S. (2020). Exploring the relationship between foreign language motivation and achievement among primary school students learning English in China. System, 89, 102199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102199 |

| 45 | Murray, L., Giralt, M., & Benini, S. (2020). Extending digital literacies: Proposing an agentive literacy to tackle the problems of distractive technologies in language learning. ReCALL, 32(3), 250–271. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344020000130 |

| 46 | Wang, H. C. (2020). Facilitating English L2 learners’ intercultural competence and learning of English in a Taiwanese university. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820969359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820969359 |

| 47 | Csizér, K., & Kontra, E. H. (2020). Foreign Language Learning Characteristics of Deaf and Severely Hard-of-Hearing Students. The Modern Language Journal, 104(1), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12630 |

| 48 | Börekci, R., & Aydin, S. (2020). Foreign language teachers’ interactions with their students on Facebook. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(3), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1557691 |

| 49 | Casal, J. E., & Kessler, M. (2020). Form and rhetorical function of phrase-frames in promotional writing: A corpus-and genre-based analysis. System, 95, 102370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102370 |

| 50 | Blume, C. (2020). Games people (don’t) play: An analysis of pre-service EFL teachers’ behaviors and beliefs regarding digital game-based language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(1–2), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1552599 |

| 51 | Rueckert, D., Pico, K., Kim, D., & Calero Sánchez, X. (2020). Gamifying the foreign language classroom for brain-friendly learning. Foreign Language Annals, 53(4), 686–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12490 |

| 52 | Chen, Y., Smith, T. J., York, C. S., & Mayall, H. J. (2020). Google Earth Virtual Reality and expository writing for young English Learners from a Funds of Knowledge perspective. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(1–2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1544151 |

| 53 | Schurz, A., & Coumel, M. (2020). Grammar teaching in ELT: A cross-national comparison of teacher-reported practices. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820964137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820964137 |

| 54 | Aizawa, I., & Rose, H. (2020). High school to university transitional challenges in English Medium Instruction in Japan. System, 95, 102390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102390 |

| 55 | Nguyen, H., & Gu, Y. (2020). Impact of TOEIC listening and reading as a university exit test in Vietnam. Language Assessment Quarterly, 17(2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2020.1722672 |

| 56 | Webb, M., & Doman, E. (2020). Impacts of flipped classrooms on learner attitudes towards technology-enhanced language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(3), 240–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1557692 |

| 57 | Kato, F., Spring, R., & Mori, C. (2020). Incorporating project-based language learning into distance learning: Creating a homepage during computer-mediated learning sessions. Language teaching research, 1362168820954454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820954454 |

| 58 | Wallace, M. P. (2020). Individual differences in second language listening: Examining the role of knowledge, metacognitive awareness, memory, and attention. Language Learning. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12424 |

| 59 | Lee, J. S. (2020). Informal digital learning of English and strategic competence for cross-cultural communication: Perception of varieties of English as a mediator. ReCALL, 32(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344019000181 |

| 60 | Lee, C. (2020). Intention to use versus actual adoption of technology by university English language learners: what perceptions and factors matter?. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1857410 |

| 61 | Pawlak, M., Kruk, M., Zawodniak, J., & Pasikowski, S. (2020). Investigating factors responsible for boredom in English classes: The case of advanced learners. System, 91, 102259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102259 |

| 62 | Pawlak, M., Kruk, M., & Zawodniak, J. (2020). Investigating individual trajectories in experiencing boredom in the language classroom: The case of 11 Polish students of English. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820914004. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820914004 |

| 63 | Wei, X., & Zhang, W. (2020). Investigating L2 writers’ metacognitive awareness about L1-L2 rhetorical differences. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 46, 100875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100875 |

| 64 | Bielak, J., & Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. (2020). Investigating language learners’ emotion-regulation strategies with the help of the vignette methodology. System, 90, 102208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102208 |

| 65 | Zaccaron, R., & Xhafaj, D. C. P. (2020). Knowing me, knowing you: A comparative study on the effects of anonymous and conference peer feedback on the writing of learners of English as an additional language. System, 95, 102367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102367 |

| 66 | Artamonova, T. (2020). L2 learners' language attitudes and their assessment. Foreign Language Annals, 53(4), 807–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12498 |

| 67 | Molway, L., Arcos, M., & Macaro, E. (2020). Language teachers’ reported first and second language use: A comparative contextualized study of England and Spain. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820913978. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820913978 |

| 68 | Brevik, L. M., & Rindal, U. (2020). Language use in the classroom: Balancing target language exposure with the need for other languages. Tesol Quarterly, 54(4), 925–953. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.564 |

| 69 | Yoshida, R. (2020). Learners’ emotions in foreign language text chats with native speakers. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1818787 |

| 70 | Banegas, D. L., Loutayf, M. S., Company, S., Alemán, M. J., & Roberts, G. (2020). Learning to write book reviews for publication: A collaborative action research study on student-teachers’ perceptions, motivation, and self-efficacy. System, 95, 102371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102371 |

| 71 | Vogt, K., Tsagari, D., Csépes, I., Green, A., & Sifakis, N. (2020). Linking learners’ perspectives on language assessment practices to teachers’ assessment literacy enhancement (TALE): Insights from four European countries. Language Assessment Quarterly, 17(4), 410–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2020.1776714 |

| 72 | Tavakoli, P. (2020). Making fluency research accessible to second language teachers: The impact of a training intervention. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820951213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820951213 |

| 73 | Zeilhofer, L. (2020). Mindfulness in the foreign language classroom: Influence on academic achievement and awareness. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820934624. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820934624 |

| 74 | Lou, N. M., & Noels, K. A. (2020). Mindsets matter for linguistic minority students: Growth mindsets foster greater perceived proficiency, especially for newcomers. The Modern Language Journal, 104(4), 739–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12669 |

| 75 | Sun, P. P., & Mei, B. (2020). Modeling preservice Chinese-as-a-second/foreign-language teachers’ adoption of educational technology: a technology acceptance perspective. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1750430 |

| 76 | Wilby, J. (2020). Motivation, self-regulation, and writing achievement on a university foundation programme: A programme evaluation study. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820917323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820917323 |

| 77 | Goodman, B. A., & Montgomery, D. P. (2020). “Now I always try to stick to the point”: Socialization to and from genre knowledge in an English-medium university in Kazakhstan. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 48, 100913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100913 |

| 78 | Kartchava, E., Gatbonton, E., Ammar, A., & Trofimovich, P. (2020). Oral corrective feedback: Pre-service English as a second language teachers’ beliefs and practices. Language Teaching Research, 24(2), 220–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818787546 |

| 79 | Mori, Y. (2020). Perceptual differences about kanji instruction: Native versus nonnative, and secondary versus postsecondary instructors of Japanese. Foreign Language Annals, 53(3), 550–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12480 |

| 80 | Tsunemoto, A., Trofimovich, P., & Kennedy, S. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about second language pronunciation teaching, their experience, and speech assessments. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820937273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820937273 |

| 81 | Schmidgall, J., & Powers, D. E. (2021). Predicting communicative effectiveness in the international workplace: Support for TOEIC® Speaking test scores from linguistic laypersons. Language Testing, 38(2), 302–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532220941803 |

| 82 | Sato, M., & McDonough, K. (2020). Predicting L2 learners’ noticing of L2 errors: Proficiency, language analytical ability, and interaction mindset. System, 93, 102301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102301 |

| 83 | Dong, J., & Lu, X. (2020). Promoting discipline-specific genre competence with corpus-based genre analysis activities. English for Specific Purposes, 58, 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2020.01.005 |

| 84 | Martin, I. A. (2020). Pronunciation Can Be Acquired Outside the Classroom: Design and Assessment of Homework-Based Training. The Modern Language Journal, 104(2), 457–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12638 |

| 85 | Bueno-Alastuey, M. C., & Nemeth, K. (2020). Quizlet and podcasts: effects on vocabulary acquisition. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1802601 |

| 86 | Tsagari, D., & Giannikas, C. N. (2020). Re-evaluating the use of the L1 in the L2 classroom: students vs. teachers. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(1), 151–181. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0104 |

| 87 | Stoller, F. L., & Nguyen, L. T. H. (2020). Reading habits of Vietnamese University English majors. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 48, 100906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100906 |

| 88 | Schmidt, L. B. (2020). Role of developing language attitudes in a study abroad context on adoption of dialectal pronunciations. Foreign Language Annals, 53(4), 785–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12489 |

| 89 | Barrett, N. E., Liu, G. Z., & Wang, H. C. (2020). Seamless learning for oral presentations: designing for performance needs. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1720254 |

| 90 | Lindberg, R., & Trofimovich, P. (2020). Second language learners’ attitudes toward French varieties: The roles of learning experience and social networks. The Modern Language Journal, 104(4), 822–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12674 |

| 91 | Jiang, L., Yu, S., & Wang, C. (2020). Second language writing instructors’ feedback practice in response to automated writing evaluation: A sociocultural perspective. System, 93, 102302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102302 |

| 92 | Yung, K. W. H., & Chiu, M. M. (2020). Secondary school students’ enjoyment of English private tutoring: An L2 motivational self perspective. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820962139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820962139 |

| 93 | Aloraini, N., & Cardoso, W. (2020). Social media in language learning: A mixed-methods investigation of students’ perceptions. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1830804 |

| 94 | Nagle, C., Sachs, R., & Zárate-Sández, G. (2020). Spanish teachers’ beliefs on the usefulness of pronunciation knowledge, skills, and activities and their confidence in implementing them. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820957037. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820957037 |

| 95 | Crane, C., & Sosulski, M. J. (2020). Staging transformative learning across collegiate language curricula: Student perceptions of structured reflection for language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 53(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12437 |

| 96 | Kessler, M., Loewen, S., & Trego, D. (2020). Synchronous VCMC with TalkAbroad: Exploring noticing, transcription, and learner perceptions in Spanish foreign-language pedagogy. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820954456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820954456 |

| 97 | Lenkaitis, C. A. (2020). Technology as a mediating tool: videoconferencing, L2 learning, and learner autonomy. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(5–6), 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1572018 |

| 98 | Pfenninger, S. E. (2020). The dynamic multicausality of age of first bilingual language exposure: Evidence from a longitudinal content and language integrated learning study with dense time serial measurements. The Modern Language Journal, 104(3), 662-686. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12666 |

| 99 | Saeedakhtar, A., Bagerin, M., & Abdi, R. (2020). The effect of hands-on and hands-off data-driven learning on low-intermediate learners’ verb-preposition collocations. System, 91, 102268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102268 |

| 100 | Pérez-Segura, J. J., Sánchez Ruiz, R., González-Calero, J. A., & Cózar-Gutiérrez, R. (2020). The effect of personalized feedback on listening and reading skills in the learning of EFL. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1705354 |

| 101 | Yang, W., & Kim, Y. (2020). The effect of topic familiarity on the complexity, accuracy, and fluency of second language writing. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(1), 79–108. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0017 |

| 102 | Chen, C. M., Li, M. C., & Lin, M. F. (2020). The effects of video-annotated learning and reviewing system with vocabulary learning mechanism on English listening comprehension and technology acceptance. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1825093 |

| 103 | Canals, L. (2020). The effects of virtual exchanges on oral skills and motivation. Language Learning & Technology, 24(3), 103–119. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44742 |

| 104 | Chen, H. J. H., & Hsu, H. L. (2020). The impact of a serious game on vocabulary and content learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(7), 811–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1593197 |

| 105 | Tai, T. Y., Chen, H. H. J., & Todd, G. (2020). The impact of a virtual reality app on adolescent EFL learners’ vocabulary learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1752735 |

| 106 | Lee, J., & Song, J. (2020). The impact of group composition and task design on foreign language learners’ interactions in mobile-based intercultural exchanges. ReCALL, 32(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344019000119 |

| 107 | Lamb, M., & Arisandy, F. E. (2020). The impact of online use of English on motivation to learn. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(1–2), 85–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1545670 |

| 108 | Zare, M., Shooshtari, Z. G., & Jalilifar, A. (2020). The interplay of oral corrective feedback and L2 willingness to communicate across proficiency levels. Language Teaching Research, 1362168820928967. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820928967 |

| 109 | Tsuchiya, S. (2020). The native speaker fallacy in a US university Japanese and Chinese program. Foreign Language Annals, 53(3), 527–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12475 |

| 110 | Vafaee, P., & Suzuki, Y. (2020). The relative significance of syntactic knowledge and vocabulary knowledge in second language listening ability. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(2), 383–410. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263119000676 |

| 111 | Schmidgall, J., & Powers, D. E. (2020). TOEIC® Writing test scores as indicators of the functional adequacy of writing in the international workplace: Evaluation by linguistic laypersons. Assessing Writing, 46, 100492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100492 |

| 112 | Kim, E. G., Park, S., & Baldwin, M. (2021). Toward successful implementation of introductory integrated content and language classes for EFL science and engineering students. TESOL Quarterly, 55(1), 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.594 |

| 113 | Smith, S. A., Foster, M. E., Baffoe-Djan, J. B., Li, Z., & Yu, S. (2020). Unifying the current self, ideal self, attributions, self-authenticity, and intended effort: A partial replication study among Chinese university English learners. System, 95, 102377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102377 |

| 114 | Shadiev, R., Wu, T. T., & Huang, Y. M. (2020). Using image-to-text recognition technology to facilitate vocabulary acquisition in authentic contexts. ReCALL, 32(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344020000038 |

| 115 | Timpe-Laughlin, V., Sydorenko, T., & Daurio, P. (2020). Using spoken dialogue technology for L2 speaking practice: what do teachers think?. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1774904 |

| 116 | Vogt, K., Tsagari, D., & Spanoudis, G. (2020). What do teachers think they want? A comparative study of in-service language teachers’ beliefs on LAL training needs. Language Assessment Quarterly, 17(4), 386–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2020.1781128 |

| 117 | Zhang, H., Wu, J., & Zhu, Y. (2020). Why do you choose to teach Chinese as a second language? A study of pre-service CSL teachers’ motivations. System, 91, 102242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102242 |

| 118 | Yeom, S., & Jun, H. (2020). Young Korean EFL learners’ reading and test-taking strategies in a paper and a computer-based reading comprehension tests. Language Assessment Quarterly, 17(3), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2020.1731753 |

Appendix H

Search Codes

| Codes | |

| Publication Name | “Applied Linguistics” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language Teaching” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Modern Language Journal” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language Learning” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Journal of Second Language Writing” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Studies in Second Language Acquisition” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language Teaching Research” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Computer Assisted Language Learning” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “English for Specific Purposes” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language Learning & Technology” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Assessing Writing” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Foreign Language Annals” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “TESOL Quarterly” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “System” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Journal of English for Academic Purposes” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “ReCALL” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language Testing” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language and Education” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Annual Review of Applied Linguistics” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language Learning and Development” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Second Language Research” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “International Multilingual Journal” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Applied Linguistics Reviews” |

| or | |

| Publication Name | “Language Assessment Quarterly” |

| Refined by | |

| Document Types | Article |

| and | |

| Topic | survey OR questionnaire |

| and | |

| Timespan | 2020 |

| and | |

| Indexes | SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI. |

References

- Dörnyei, Z.; Taguchi, T. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, E. Survey Research. In Research Methods in Applied Linguistics: A Practical Resource; Paltridge, B., Phakiti, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, S.M.; Mackey, A. Data Elicitation for Second and Foreign Language Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ruel, E.; Wagner, W.E., III; Gillespie, B.J. The Practice of Survey Research: Theory and Applications; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; McGeown, S. Exploring the relationship between foreign language motivation and achievement among primary school students learning English in China. System 2020, 89, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.; Doman, E. Impacts of flipped classrooms on learner attitudes towards technology-enhanced language learning. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 33, 240–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.M. Online Questionnaires. In The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Linguistics Research Methodology; Phakiti, A., De Costa, P., Plonsky, L., Starfield, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sudina, E. Study and Scale Quality in Second Language Survey Research, 2009–2019: The Case of Anxiety and Motivation. Lang. Learn. 2021, 71, 1149–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phakiti, A. Quantitative Research and Analysis. In Research Methods in Applied Linguistics: A Practical Resource; Paltridge, B., Phakiti, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Five Perspectives on Validity Argument. In Test Validity; Wainer, H., Braun, H., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Messick, S. The Once and Future Issues of Validity: Assessing the Meaning and Consequences of Measurement. In Test Validity; Wainer, H., Braun, H., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Messick, S. Meaning and values in test validation: The science and ethics of assessment. Educ. Res. 1989, 18, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Educational Research Association; American Psychological Association; National Council on Measurement in Education. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, M.T. Validating the Interpretations and Uses of Test Scores. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 50, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulmin, S.E. The Uses of Argument; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, C.J. Language Testing and Validation: An Evidence-Based Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, B.; Weir, C.J. Test Development and Validation. In Language Testing: Theories and Practice; O’Sullivan, B., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aryadoust, V. Building a Validity Argument for a Listening Test of Academic Proficiency; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle, C.A.; Enright, M.K.; Jamieson, J.M. Building a Validity Argument for the Test of English as a Foreign Language; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Addey, C.; Maddox, B.; Zumbo, B.D. Assembled validity: Rethinking Kane’s argument-based approach in the context of International Large-Scale Assessments (ILSAs). Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2020, 27, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, C.A.; Enright, M.K.; Jamieson, J. Does an Argument-Based Approach to Validity Make a Difference? Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 2010, 29, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, C.A. Validity in Language Assessment. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Language Testing; Winke, P., Brunfaut, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Sun, Y. Interpreting the Impact of the Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test on Second Language Students Within an Argument-Based Validation Framework. Lang. Assess. Q. 2015, 12, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Slatyer, H. Test validation in interpreter certification performance testing: An argument-based approach. Interpreting 2016, 18, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A. Not to scale? An argument-based inquiry into the validity of an L2 writing rating scale. Assess. Writ. 2018, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryadoust, V.; Goh, C.C.; Kim, L.O. Developing and validating an academic listening questionnaire. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2012, 54, 227–256. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, J. The Dirty Laundry of ESL Survey Research. TESOL Q. 1990, 24, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergrift, L.; Goh, C.C.M.; Mareschal, C.J.; Tafaghodtari, M.H. The Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire: Development and Validation. Lang. Learn. 2006, 56, 431–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.S.; Zhang, L.J. Fostering Strategic Learning: The Development and Validation of the Writing Strategies for Motivational Regulation Questionnaire (WSMRQ). Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 2015, 25, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.S.; Zhang, L.J. A Questionnaire-Based Validation of Multidimensional Models of Self-Regulated Learning Strategies. Mod. Lang. J. 2016, 100, 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-S. Development and preliminary validation of four brief measures of L2 language-skill-specific anxiety. System 2017, 68, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, J.F.; Henderson, D.B. Rasch Analysis of the Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ). Int. J. List. 2019, 33, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Plonsky, L. Statistical assumptions in L2 research: A systematic review. Second Lang. Res. 2021, 37, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Aryadoust, V. A review of the methodological quality of quantitative mobile-assisted language learning research. System 2021, 100, 102568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryadoust, V.; Mehran, P.; Alizadeh, M. Validating a computer-assisted language learning attitude instrument used in Iranian EFL context: An evidence-based approach. Comput. Assist. Lang. 2016, 29, 561–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryadoust, V.; Shahsavar, Z. Validity of the Persian blog attitude questionnaire: An evidence-based approach. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Meth. 2016, 15, 417–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.A.; Merzdorf, H.E.; Hicks, N.M.; Sarfraz, M.I.; Bermel, P. Challenges to assessing motivation in MOOC learners: An application of an argument-based approach. Comput. Educ. 2020, 150, 103829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wind, S.; Peterson, M.E. A systematic review of methods for evaluating rating quality in language assessment. Lang. Test. 2017, 35, 161–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Rollins, J.; Yan, E. Web of Science use in published research and review papers 1997–2017: A selective, dynamic, cross-domain, content-based analysis. Scientometrics 2017, 115, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, M.; Shi, L.; Haggerty, J. Analysis of the empirical research in the journal of second language writing at its 25th year (1992–2016). J. Second Lang. Writ. 2018, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Yan, X. Assessing Speaking Proficiency: A Narrative Review of Speaking Assessment Research Within the Argument-Based Validation Framework. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phakiti, A.; Paltridge, B. Approaches and Methods in Applied Linguistics Research. In Research Methods In Applied Linguistics: A Practical Resource; Paltridge, B., Phakiti, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, W. Investigating L2 writers’ metacognitive awareness about L1-L2 rhetorical differences. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 2020, 46, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.; Li, M.-C.; Lin, M.-F. The effects of video-annotated learning and reviewing system with vocabulary learning mechanism on English listening comprehension and technology acceptance. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 35, 1557–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, L.S.; Yuan, R.E.; Sun, P.P. A mixed-methods approach to investigating motivational regulation strategies and writing proficiency in English as a foreign language contexts. System 2020, 88, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaee, P.; Suzuki, Y. The Relative Significance of Syntactic Knowledge and Vocabulary Knowledge in Second Language Listening Ability. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2020, 42, 383–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenninger, S.E. The Dynamic Multicausality of Age of First Bilingual Language Exposure: Evidence From a Longitudinal Content and Language Integrated Learning Study With Dense Time Serial Measurements. Mod. Lang. J. 2020, 104, 662–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, C. College students’ writing self-efficacy and writing self-regulated learning strategies in learning English as a foreign language. System 2020, 90, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artamonova, T. L2 learners’ language attitudes and their assessment. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2020, 53, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clow, K.; James, K. Essentials of Marketing Research: Putting Research into Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dalati, S.; Gómez, J.M. Surveys and Questionnaires. In Modernizing the Academic Teaching and Research Environment; Gómez, J.M., Mouselli, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Khany, R.; Tazik, K. Levels of Statistical Use in Applied Linguistics Research Articles: From 1986 to 2015. J. Quant. Linguist. 2019, 26, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Research. In The Sage Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods; Bickman, L., Rog, D.J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2009; pp. 283–317. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Greer, J.L. Mixed Methods Research and Analysis. In Research Methods in Applied Linguistics: A Practical Resource; Paltridge, B., Phakiti, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, A.; Bryfonski, L. Mixed Methodology. In The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Linguistics Research Methodology; Phakiti, A., De Costa, P., Plonsky, L., Starfield, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, W.; Chen, B.; Shu, F. Publish or impoverish. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 69, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Borg, E.; Borg, M. Challenges and coping strategies for international publication: Perceptions of young scholars in China. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 42, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Quan, W.; Chen, B.; Qiu, J.; Sugimoto, C.R.; Larivière, V. The role of Web of Science publications in China’s tenure system. Scientometrics 2020, 122, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A. Spread of English across Greater China. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2012, 33, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, J.J. Exploring the spread of English language learning in South Korea and reflections of the diversifying sociolinguistic context for future English language teaching practices. Asian Engl. 2019, 21, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A.; Walls, R.T.; Hill, L.A. Early relationships among self-regulatory constructs: Theory of mind and preschool children’s problem solving. Child Study J. 2000, 30, 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Escolano-Pérez, E.; Herrero-Nivela, M.L.; Anguera, M.T. Preschool Metacognitive Skill Assessment in Order to Promote Educational Sensitive Response From Mixed-Methods Approach: Complementarity of Data Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, E.; Laxaraton, A. The Research Manual: Design and Statistics for Applied Linguistics; Newbury House: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ness Evans, A.; Rooney, B.J. Methods in Psychological Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M. Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 7, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Savalei, V. Improving the Factor Structure of Psychological Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2015, 76, 357–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hoorie, A.H.; Vitta, J.P. The seven sins of L2 research: A review of 30 journals’ statistical quality and their CiteScore, SJR, SNIP, JCR Impact Factors. Lang. Teach. Res. 2018, 23, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using Ibm Spss Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M.J.; Yen, W.M. Introduction to Measurement Theory; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aryadoust, V.; Ng, L.Y.; Sayama, H. A comprehensive review of Rasch measurement in language assessment: Recommendations and guidelines for research. Lang. Test. 2021, 38, 6–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messick, S. Test validity and the ethics of assessment. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 1012–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D. Using Surveys in Language Programs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, W.J. Rasch Analysis for Instrument Development: Why, When, and How? CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, rm4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizumoto, A.; Takeuchi, O. Adaptation and Validation of Self-regulating Capacity in Vocabulary Learning Scale. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 33, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T. Exploratory Factor Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Plonsky, L. Study Quality in SLA. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2013, 35, 655–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, S.; Lavolette, E.; Spino, L.A.; Papi, M.; Schmidtke, J.; Sterling, S.; Wolff, D. Statistical Literacy Among Applied Linguists and Second Language Acquisition Researchers. TESOL Q. 2013, 48, 360–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonulal, T.; Loewen, S.; Plonsky, L. The development of statistical literacy in applied linguistics graduate students. ITL Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 168, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F.; Coutts, J.J. Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Commun. Methods Meas. 2020, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizano-Hermosilla, I.; Alvarado, J.M. Best Alternatives to Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability in Realistic Conditions: Congeneric and Asymmetrical Measurements. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Chan, W. Testing the Difference Between Reliability Coefficients Alpha and Omega. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 77, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryadoust, V. The vexing problem of validity and the future of second language assessment. Lang. Test. in press.

| Inclusion Criteria: The Paper … |

|---|

| 1. Was a peer-reviewed journal article; |

| 2. Was relevant to second and foreign language learning, teaching or assessment; |

| 3. Had a quantitative or mixed research design; |

| 4. Employed at least one questionnaire. |

| Journal | # Number of Papers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Language Teaching Research | 25 | 21.19 |

| Computer Assisted Language Learning | 24 | 20.34 |

| System | 18 | 15.25 |

| Foreign Language Annals | 9 | 7.63 |

| Journal of English for Academic Purposes | 7 | 5.93 |

| The Modern Language Journal | 5 | 4.24 |

| Language Assessment Quarterly | 4 | 3.39 |

| RECALL | 4 | 3.39 |

| Applied Linguistics Review | 3 | 2.54 |

| Assessing Writing | 3 | 2.54 |

| English for Specific Purposes | 3 | 2.54 |

| Language Learning and Technology | 3 | 2.54 |

| Language Testing | 3 | 2.54 |

| Journal of Second Language Writing | 2 | 1.69 |

| Studies in Second Language Acquisition | 2 | 1.69 |

| TESOL Quarterly | 2 | 1.69 |

| Language Learning | 1 | 0.85 |

| Inter-Rater Agreement Rate | Intra-Rater Agreement Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| Research design | 91.67% | 95.83% |

| Language status | 87.50% | 87.50% |

| Target language | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Location of the study | 100.00% | 95.83% |

| Educational level | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Participants status | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Sample size | 83.33% | 91.67% |

| Item number | 83.33% | 70.83% |

| Item type | 91.67% | 91.67% |

| Source of the questionnaires | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Domain | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Type of data | 83.33% | 83.33% |

| Evaluation | 91.67% | 91.67% |

| Generalization | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Alpha value | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Explanation | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Validity Evidence | Number of Studies | % |

|---|---|---|

| Domain description | ||

| Attitudinal | 45 | 38.14 |

| Attitudinal + behavioral + factual | 25 | 21.19 |

| Attitudinal + factual | 20 | 16.95 |

| Attitudinal + behavioral | 19 | 16.10 |

| Behavioral + factual | 5 | 4.24 |

| Behavioral | 4 | 3.39 |

| Evaluation | ||

| Mixed | 59 | 50.00 |

| Likert scale | 52 | 44.07 |

| Multiple choice | 2 | 1.69 |

| Frequency count | 3 | 2.54 |

| 1000-Point sliding scale | 1 | 0.85 |

| Thematic analysis | 1 | 0.85 |

| Generalization | ||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 65 | 55.08 |

| Rasch item reliability | 1 | 0.85 |

| N/A | 52 | 44.07 |

| Explanation | ||

| EFA | 9 | 7.63 |

| PCA | 9 | 7.63 |

| CFA | 8 | 6.78 |

| CFA + EFA | 5 | 4.24 |

| Correlation | 3 | 2.54 |

| EFA + PCA | 2 | 1.69 |

| Rasch | 2 | 1.69 |

| EFA + CFA + correlation | 1 | 0.85 |

| FA | 1 | 0.85 |

| PCA + CFA + Rasch | 1 | 0.85 |

| N/A | 77 | 65.25 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha Value | # Number of Studies | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0.6–0.668 | 3 | 4.84 |

| 0.724–0.799 | 12 | 19.35 |

| 0.8–0.89 | 33 | 53.23 |

| 0.9–0.96 | 14 | 22.58 |

| Domain Description | Evaluation | Generalization | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptors | Construct that the questionnaire is intended to measure | Response options provided by the questionnaires to assign numerical values to psychological attributes | The generalizability of the observed scores of the questionnaires | Whether the questionnaire actually measures the theoretical construct it claims to measure |

| Evidence | The relevant literature | Statistical or psychometric analyses that support the functionality of the scales | Reliability studies and generalizability theory | Dimensionality analysis |

| Results | 100% | 57.63% | 55.93% | 34.75% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Aryadoust, V. A Systematic Review of the Validity of Questionnaires in Second Language Research. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100723

Zhang Y, Aryadoust V. A Systematic Review of the Validity of Questionnaires in Second Language Research. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(10):723. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100723

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yifan, and Vahid Aryadoust. 2022. "A Systematic Review of the Validity of Questionnaires in Second Language Research" Education Sciences 12, no. 10: 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100723

APA StyleZhang, Y., & Aryadoust, V. (2022). A Systematic Review of the Validity of Questionnaires in Second Language Research. Education Sciences, 12(10), 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100723