1. Introduction

As an evolving and contested field of knowledge [

1], urban design is subject to a range of infiltrations, appropriations, and burgeoning claims by more established disciplines and professions such as architecture and urban planning [

2]. Similar to the field itself, urban design education and its pedagogies are subject to forms of adaptation depending on the faculties, schools, and/or departments hosting the field of urban design and what they expect it to become. While one can find quite different versions of urban design education across different contexts and higher education institutions, one thing that is important to note is that design studios have largely remained integral and central to urban design education and its multiple pedagogies. Exploring design studios is particularly at stake as design studio pedagogy has the capacity to convey the values of the related design professions and the broader society [

3] (p. 3). The design studio represents real-world practice but it is somewhat free of its risks [

4] (p. 5). As Lang [

5] (p. 76) puts it, there are not any substitutes for the problem-solving and learning-by-doing experiences of the design studios. This paper primarily engages with design studio pedagogy with a focus on the design and delivery of blended urban design studios in relation to student perceptions and experiences in the context of urban design education.

This paper draws on the view that exploring and reflecting on student perceptions and teaching experiences can effectively inform the development of future learning and teaching activities and materials in the context of design studio pedagogy [

6,

7,

8]. The aim is to discuss the capacities and challenges of learning and teaching urban design through studio pedagogy with a focus on student perceptions and teaching experiences associated with blended urban design studios, which incorporate a mix of face-to-face and synchronous/asynchronous online learning activities. This is part of a broader study that seeks to address the key gaps and questions of “what to teach” and “how to teach” through studio pedagogy in urban design education. The focus on “what to teach” is as critical as the focus on “how to teach”, particularly in relation to the built environment and design professions since the “content of” and the “approach to” the education of the related fields work as a foundation for shaping responsive environments [

3] (p. 6). As part of this study, two constructively aligned and blended urban design studios were designed and delivered in a one-year full-time MA Urban Design (MAUD) programme during the COVID-19 in the UK. This paper aims to open the discussion regarding these understudied questions with a focus on urban design studio pedagogy and to provide insights regarding the design and delivery of blended studio-based modules.

The paper draws on empirical research from a critical case study of urban design studios in the 2021–2022 academic year as part of the postgraduate MAUD programme at Cardiff University, which is one of the largest postgraduate programmes of its kind jointly delivered by the Welsh School of Architecture and the School of Geography and Planning. Building upon an earlier study on student experiences and perceptions in the context of blended design studio pedagogy [

6], this paper discusses the design and delivery of the two constructively aligned and blended design studios on the topic of transit urban design in relation to the results of an online survey undertaken as part of the broader study. The urban design studios primarily focused on one of the key strategic sites (namely “Cardiff Central Enterprise Zone and Regional Transport Hub”) in the Local Development Plan, which was adopted by the Cardiff Council in 2016. The selection of transit urban design as the overarching topic of both design studios is guided by the following two premises: (1) transit urban design is a significant approach to address the critical challenges of promoting sustainable mobilities and transforming car-dependent cities [

9,

10,

11]; (2) urban design education and studio pedagogy should prepare future urban designers to effectively engage with understanding and shaping places surrounding transit nodes and corridors. With a primary focus on the related learning and teaching experiences, this paper contributes a critical case study of designing and delivering blended urban design studios in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research findings can inform the development of a pedagogical framework for designing blended studios in the future and offer research-informed lessons regarding the capacities and challenges associated with learning and teaching urban design through studio pedagogy.

This paper is structured into six sections. The introduction section is followed by a review of the relevant literature focusing on some of the key issues associated with design studio pedagogy. The section on literature review is then followed by a detailed discussion of the research design approach and methods used as part of this study to collect and analyse the related data. A part of this section is about the design and dissemination of an online survey as a tool deployed for data collection. The section following the discussion of the research design and methods begins by explaining the design and delivery of the urban design studios and illustrating their relations as well as the key learning activities. In this section, the paper also draws on the relevant results of the online survey to discuss the design and delivery of urban design studios. It concludes by discussing the key findings of the study in the context of the relevant literature. The section on discussion and conclusion is followed by outlining the key limitations and future research directions.

2. Design Studio Pedagogy

As a key component of the built environment pedagogy and education, design studios offer students a setting where they can learn and/or test a range of ideas and skills that are fundamental to the creative acts of design and planning [

12]. In design studios, students can bring together all their learning from other modules and explore the ways to use that knowledge as a professional. Studios also enable individual learners to engage with creating urban design proposals for certain urban environments and responding to complex existing problems with the aim of creating well-designed places that are weighed against competing values [

13]. Design studios can be considered ideal settings for encouraging critical thinking [

14]. In what follows, the paper engages with the relevant literature on different aspects that have been argued to play an important role in urban design studio pedagogy and education. In line with the scope and focus of this paper, the literature review is structured to discuss the relevant body of knowledge engaging with the role of digital technology, review of policies, field study visits, the mix of students, design studio topic and locality, learning from urban design precedents, and community engagement in the context of design studio pedagogy.

The potential of digital technology in relation to urban design learning and teaching is not neglected in the existing literature. Mapua Lim et al. [

15] examine a range of pedagogical methods which adopt new digital technologies and media in the context of urban design teaching and learning. They argue that such pedagogical innovations, including video for research and interactive PDFs, mobile lectures, townscape through video, and website design, can enable students to become design responsive and creative future practitioners. The unprecedented spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has also engendered the widespread use of digital technology for urban design pedagogical transformations and course redesigns [

16,

17]. More particularly, the innovations in the adoption of digital technology have had major impacts on the ways in which emerging city designers think and experience urban spaces as part of their design studio education [

6,

7].

The use of big data can become challenging particularly in the context of design studios. This relates to the fact that much time may be needed to effectively absorb, sift, and interpret those data [

18]. In their critique of the confusion between means and ends in the context of urban design thinking, Dovey [

19] argues that digital technology needs to be seen as a means (rather than ends) that can help with producing information and as such can enable better understanding and transformation of cities. It is important to note that the greatest urban design pedagogy avoids reductionist approaches towards cities and defies supporting the production of seductive yet impossible urban images masquerading as urban design [

19].

There has been limited scholarly focus on the role of policy review in teaching and learning urban design in the context of design studio pedagogy. Some may perceive that urban design studios should avoid including learning and teaching activities that fall within the regulatory and policy realms. Whitzman [

20] (p. 575), however, points out that “the human scale of urban design is nested within larger metropolitan, national and global strategic planning and governance challenges”. Drawing on their comprehensive study of design policies in development plans of the 1990s, Punter and Carmona [

21] outline the fundamental role of design within the English planning system and argue for a comprehensive treatment of design within the local development plans.

Moudon [

22] (p. 693) introduces the laboratory pedagogic model as an alternative to the traditional model, suggesting that geospatial data “preempt the need for initial field work that characterised the first steps of urban design research”. Such enhanced accessibility to big data has been argued to expand the frontiers of urban design thinking from a traditional focus on certain places or urban areas to include entire cities or city-regions. Macdonald [

13] however believes that some of the data collection regarding particular contexts (e.g., the related area’s history, physical form, socio-economic dynamics, and how the access and movements work) in the design studio environment must be undertaken through the students’ own field site visits such as observation, counting, surveys, and measurement. Following this data gathering approach can expose students to different insights as they spend time in the related place rather than simply analysing abstract secondary datasets. It is also recommended that students prepare a graphic presentation of their key findings (e.g., preparation of a reconnaissance map articulating their first impressions of the study area) and rigorously examine and select the data they have collected to address what critical “stories” they have unravelled rather than simply presenting a “data dump” of everything that they have explored in their field site visits [

13].

The role of field study visits in urban design modules such as studios that focus on informality has been discussed in the recent literature. Despite their time-consuming nature, field site visits can enable future urban designers to experience on the ground and more effectively engage with the realities and challenges of urban informality [

23]. Field study visits cannot be simply replaced by secondary data in which narratives of urban design projects may become promotional to propagate certain viewpoints [

2]. In effect, engaging with national and international field study visits can be useful for urban design students as it can enable a productive confrontation between the shared body of knowledge in the field and the conditions of the real world [

2].

The diversity of students in terms of educational backgrounds in the context of design studio pedagogy and education has been discussed in a few studies. According to Roberts [

18], student diversity in the context of the UK has been a product of a neo-liberalist agenda, which considers higher education as a commodity meant for trade rather than a “public good” benefiting its citizens and the larger society. Drawing on the experience of urban design studio teaching within the two-year postgraduate city planning programmes in the context of the US and Canada, Macdonald [

13] argues that a mix of learners from a wide range of educational backgrounds and with different interests is important to the urban design studio teaching and learning. This level of mix has been outlined as fruitful because it creates an environment where different skills, perspectives and ways of understanding urbanism can be translated to the “drawing board” [

13]. Drawing on some papers on the themed issue of urban design education, Strickland [

24] calls for the need to diversify student enrolment for the postgraduate urban design programmes to reflect the inter-disciplinary nature of urban design that cuts across the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, civil engineering, real estate development among other fields. It has also been noted that the peer learning promoted through this approach can broaden the future urban designers’ understanding of the field [

24]. Nevertheless, there has been limited focus on exploring the capacity of diverse cohorts including students with non-design backgrounds in the context of design studio education.

It has been suggested that to prepare students to embrace urban design as a global practice, it is important that urban design programmes admit students with a wide range of national backgrounds [

24]. Such a condition of internationalisation and the related learning and teaching that take place between students can work as a key educational tool in the context of design studios, which offer exposure to global urban conditions and cultural contexts [

24]. While the capacities of a diverse cohort of students in terms of educational and cultural backgrounds have been explored in some of the relevant literature, there have been limited studies discussing the challenges associated with communication and language barriers in the context of design studio pedagogy.

Topicality and easy access are outlined as key criteria for the selection of the place that the design studio focuses on [

13]. Accessible places encourage students to explore the study area using their own senses that are conducive to direct knowledge building (rather than relying on secondary data collected by others). Students can immerse themselves in a place particularly when there are real immediate issues associated with it as this provides the possibility that their projects can play a key role in real-world design and planning processes [

13]. Hence, it is important that design studio sites are selected from those places that face major development challenges where critical ecological concerns can be dealt with, or where major public infrastructure projects are in the pipeline. The idea of focusing on one place such as a major corridor or a neighbourhood-scale area for the whole semester of the design studio is put forward by Macdonald [

13] due to the fact that it provides opportunities for students to deeply engage and explore the selected place.

It has widely been discussed that the study of completed design projects—commonly called “design precedents”—can work as a useful tool to enable meaningful learning in the design studio environment [

25,

26,

27]. As Akin et al. [

28] argue, precedents serve as a tool for early investigation in the design process, enabling designers to harness their activity without confronting the problem of “reinventing the wheel”. This form of instruction makes a distinction between design education and other academic disciplines as “students are directed to a corpus of desirable outcomes rather than principles or theories. Based on this, they are expected to produce similar results with novel features” [

25] (p. 409). Macdonald [

13] discusses that postgraduate students often have limited personal experience of cities and can greatly benefit from looking at precedents, which works as a useful pedagogical tool to gain knowledge of innovative approaches to designing cities. It is suggested that an intensive time (e.g., a week) be dedicated to the activity of collecting relevant data and visual images about a range of precedents which can have learning lessons regarding the selected study area [

13]. Students can collectively brainstorm issues related to the design studio topic that they aim to further understand along with identifying certain places or design projects where these issues have previously been addressed by adopting innovative ways. While methods of gathering precedent information and the nature of information being assembled have primarily been web-based in recent decades [

27], it is suggested that the use of creative resources and collective knowledge can help students learn about (and be inspired by) a range of design ideas [

13]. It is, however, important to make note of the limitation of precedents in the context of urban design studios as they “remain detached from the personal experience of the designer and lack the emotional stimuli that implant a lingering memory or a visceral lasting impression of urban space” [

27] (p. 90).

A certain kind of urban design is motivated by a community-based approach, which as Talen [

29] argues, is primarily focused on promoting a sense of caring about an urban place and creating healthy neighbourhoods and public realms as social units. The value of community outreach and participation has attracted some attention in the context of design studio pedagogy and education. Effective interaction between students and community groups can in some cases result in changes in world views for both parties [

18]. Such meaningful interactions can also become impactful for local policies, development plans and design projects. The project by Loukaitou-Sideris and Mukhija [

23] on exploring spatial solutions and effective accommodation of informal street vending activities in Los Angeles shows the working-togetherness of postgraduate design studio students, street vendors, and the wider community with a view to lobby the local authorities and create new spaces. In the context of this urban design studio, students became involved in dialogue with community groups and benefitted from the local knowledge and input in developing their design proposals, some of which were later implemented by the city [

23].

The issue of community engagement in the context of urban design studio environments can pose multiple challenges. As discussed by Macdonald [

13], learning outcomes and design studio schedules may not necessarily be consistent with the immediate neighbourhood issues or planning processes in the real world. As such, it is important to be mindful of the risk of community-based urban design studios in creating unrealistic hopes and expectations that cannot be delivered upon [

13,

23]. Usually, the project is completed once the studio is over except in those cases where there are specific centres at the university level or professors and students who are dedicated to undertaking work for the public good and working alongside local communities. Another challenge relates to the fact that it is not feasible to simply offer these community-based design studios within the narrow timespan of 10 weeks (academic quarter) rather than 15 or 20 weeks [

23].

Thus far, the paper has engaged with the relevant body of knowledge exploring the role of digital technology, review of policies, field study visits, the mix of students, design studio topic and locality, learning from urban design precedents, and community engagement in the context of design studio pedagogy. In what follows, the research design and methods will be communicated in relation to the scope and focus of this paper. The section on methods will then be followed by discussing the case study analysis and survey results.

3. Research Design and Methods

This study is part of an exploratory project, adopting a case study research design and mixed methods approach. This approach is used to effectively “describe and diagnose” processes by observing their developments as well as contextual influences [

30]. The importance of deploying a case study research design has previously been highlighted in the context of higher education studies [

6,

16,

17]. Timmons and Cairns [

31] discuss the ways in which such an approach can provide education researchers with opportunities to develop learning and teaching standards and policies. This has also been argued to enable educators to gain a range of experiences to manage and respond to different situations in the classroom.

An “information-oriented strategy” [

32] is deployed for the selection of urban design studios. The urban design studios in the 2021–2022 MAUD programme at Cardiff University have been considered as a “critical” case study in the context of design studio pedagogy and urban design education since the programme is one of its kind due to its large size, structure, and international appeal, among others. Such a selection, as Flyvbjerg [

32] argues, allows logical deductions, and increases the possibility to formulate a generalisation characteristic of the selected case. Access to the selected case study and familiarity with the context at both the programme level and module level were also among the key selection criteria. The authors of this paper served as both the directors of the MAUD programme and the leaders of the urban design studio modules at Cardiff University in the 2021–2022 academic year.

The value of student experience for the higher education learning and teaching community has been discussed in the existing literature [

6,

17,

33]. As part of the research project, the perceptions and experiences of the 2021–2022 MAUD students regarding the blended design and delivery of the urban design studios were explored in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. An online survey was designed accordingly in relation to the scope and focus of the project. After receiving the Institutional Research Ethics review approval from the Welsh School of Architecture Research Ethics Committee at Cardiff University (SREC reference: 21105), the online survey was disseminated so that interested students would be able to participate and complete the survey. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. Students were also provided with the possibility to refuse to answer any questions or to withdraw from the survey at any time. Participants were also informed about the research aim and questions and were assured that their responses would be kept confidential in compliance with the relevant ethical principles and considerations. It was stressed that participation in the online survey would in no way affect their design studio assessments. Using Google Forms, the survey was designed and developed with closed-ended Likert-scale questions to explore student perceptions and experiences concerning the capacities and challenges of blended learning and teaching activities, field study visits, workshops, student-student and student-instructor interaction, assessment and feedback, and digital platforms, among others.

The online survey comprised the total target population of about 100 students in the urban design studios in the 2021–2022 academic year. To ensure accessibility, an initial invitation email and subsequent reminder emails, including the relevant information and the survey link were sent to the enrolled students using their university email addresses. Further reminders were shared with potential participants during the live online lectures and discussion sessions by the module leaders and/or studio tutors. 50 responses were collected from students, comprising 33 female (66%) and 17 male (34%) participants. Most participants (96%) considered themselves as international students. This is relatively consistent with the significant number of international students enrolled in the programme in the 2021–2022 academic year.

4. Case Study Analysis and Results

This section explains the design and delivery of the two constructively aligned postgraduate urban design studios as part of the 2021–2022 MAUD programme at Cardiff University during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK by outlining the relations between the two studios along with the key learning activities. It will then draw on the relevant results of the online survey to delineate the design and delivery of the urban design studios in relation to the timetabled activities, assessment and feedback, and digital platforms.

4.1. Designing the Relations and Learning Activities

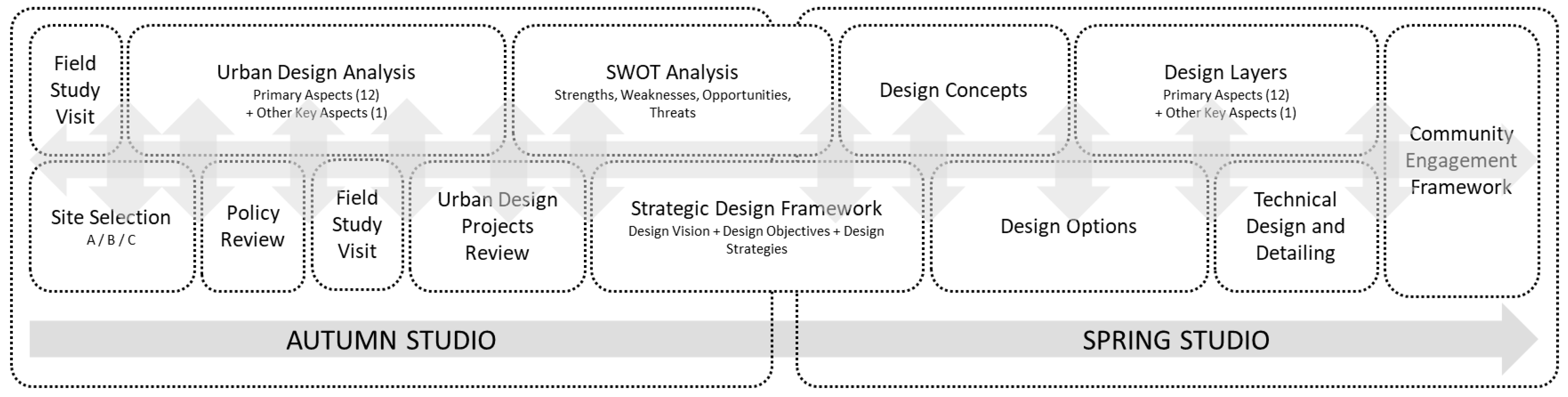

The urban design studios (namely “Autumn Studio” and “Spring Studio”) were closely linked to each other and primarily developed and delivered using a blended approach, which included a mix of carefully selected face-to-face and online learning and teaching activities to meet the related learning outcomes.

Figure 1 illustrates the relations between the two urban design studios along with some of the key learning activities. Transit urban design was selected as the overarching topic of both design studios due to its significance as an approach to engage with the challenge of promoting sustainable mobilities and transforming car-dependent cities [

9]. In addition to the same overarching topic, studio sites and urban design aspects outlined for the urban design studios remained the same in both studios to enable continuation throughout the process, avoid unnecessary repetitions of certain learning and teaching activities, support the incremental development of relevant skills, and ensure consistency across different tutorial sections. While each of the two studios included a range of different activities, the key learning and teaching activities designed for the Spring Studio built upon the key learning and teaching activities designed for the Autumn Studio (

Figure 1). As the leaders of both urban design studios, the authors of this paper worked with about 100 students and 12 studio tutors in each of the urban design studios.

Drawing on some of the key sources in the field of urban design, particularly Carmona [

34], Dovey [

35], Dovey et al. [

36], and Black and Sonbli [

37], a number of constructively aligned learning activities were designed for the studios. This process began from the views that our professional knowledge should primarily be in connection with the built environment [

38] (p. 17) and that a poor understanding of urban morphology can lead to poor design interventions [

39]. As Kropf [

40] points out, a sophisticated understanding of the ways in which places work can put us in a better position when it comes to formulating design interventions. The attempt in the process of designing the urban design studios was to encourage looking hard at cities [

41], enable a critical engagement with “design-level theories” [

42], and avoid the valorisation of the large scale over the small [

43]. The urban design studios engaged with a range of activities, including analysing the urban design topic and the context in relation to certain urban design aspects as well as identifying and analysing relevant literature, including urban design projects, to develop spatially grounded and contextually responsive urban design interventions and examine the proposed design interventions. It was critical to justify urban design decisions in the context of the relevant literature and construct informed arguments. The studios also included structuring an urban design portfolio and communicating the urban design analyses and interventions using a range of relevant presentations. The following lists the key learning activities in relation to the Autumn studio (learning activities 1–6) and Spring studio (learning activities 7–11) respectively:

Site selection and justification. This included selecting one of the “Alternative Sites” and justifying why the selected site was chosen for the urban design studios. The key strategic site (i.e., “Cardiff Central Enterprise Zone and Regional Transport Hub”) was divided into three alternative sites in relation to the aim and scope of the urban design studios. Students individually selected one of the three alternative sites for their urban design studios.

Undertaking urban design analysis in relation to all of the “Primary Aspects” and one of the “Other Key Aspects” outlined for the urban design studios.

Table 1 lists the “Primary Aspects” along with the “Other Key Aspects”. An extended list of relevant readings was also developed in relation to each of the listed aspects so that both students and studio tutors would be able to explore the outlined aspects further.

Identifying and reviewing the related policies and key documents, including the Cardiff Local Development Plan (2006–2026) and Placemaking Wales Guide (2020) as well as the relevant national/regional/local policies in relation to the context and studio site.

Identifying and reviewing precedents. This included relevant urban design projects on transit-oriented urban intensification, public space design, and city centre regeneration, among others.

Undertaking SWOT analysis. This included identifying Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats based on the urban analyses.

Developing a strategic design framework in relation to the selected studio site [

37]. This included developing an informed design vision and identifying relevant design objectives in relation to the context and urban analyses. This also included developing contextually responsive and spatially grounded design strategies in relation to the design vision and objectives and informed by the relevant literature as well as the related urban analyses.

Revisiting and revising the SWOT analysis and strategic design framework. This included critically reflecting on the SWOT analysis and strategic design framework developed as part of the Autumn Studio and, as appropriate, revising them based on the provided feedback as part of the Spring Studio.

Developing relevant design concepts and design options [

37]. This included developing informed, creative, and appropriate design concepts and design options in relation to the (revised) strategic design framework, context, and urban analyses.

Developing justified design layers in relation to all of the “Primary Aspects” and one of the “Other Key Aspects” (

Table 1). The selected aspect from the list of “Other Key Aspects” would be the same as the one selected in the Autumn Studio.

Developing technical design and detailing [

37]. This included developing technical design for parts of the selected site. Multiple locations within the selected site could be selected for detailing as appropriate.

Developing a community engagement framework in relation to the project. This included identifying the key stakeholders, how and when they can be engaged, the related resources and timeline, the level of engagement required, the ways in which disenfranchised groups can be involved, and the role of the related experts in facilitating the process [

34].

4.2. Blended Mode of Delivery and Survey Results

Thus far, the key focus has been on the relations between the two constructively aligned urban design studios and engagement with the design of the key learning activities. In what follows as part of this section, the paper draws on the key results of the online survey to elucidate the delivery of the urban design studios in relation to the timetabled activities, assessment and feedback.

The key learning and teaching activities that took place in the urban design studios included Field Study Visits (FSVs), small group studio tutorials, small group reading seminars, and lectures/guest lectures. The FSVs were primarily designed to enable students to get a first-hand experience of visiting the studio sites in Cardiff. Each studio section (8–9 students) had the opportunity to explore the studio sites with their studio tutor, take field notes, and capture photos during their visits. Two FSVs were designed (week 1 and week 4) to provide opportunities for students to explore different parts of the studio sites, engage with different aspects, go into more detail on different days, and make informed decisions regarding the selection of a site for their projects. Students were often asked to keep a diary or sketchbook which could be helpful in shaping discussions in the studio tutorials. Studio tutors often encouraged their students to discuss the outcomes of the FSVs (including supportive photos or sketches) and present their works. According to the survey results, a large number of respondents (90%) thought that FSVs were helpful for their learning experience.

The face-to-face studio tutorials took place in the allocated 12 parallel studio spaces, enabling peer learning and discussions in studio sections. Each studio section (8–9 students) was divided into two groups (each group with 4–5 students) to provide more quality time for individual feedback as well as small group discussions and interactions. The results of the survey indicate a high level of student satisfaction with the provided capacity for peer interaction (92%) in the context of face-to-face weekly studio tutorials. Urban design studios included face-to-face reading seminars in small groups where individual learners discussed up to two readings per week with their tutors and peers. These readings were particularly selected in relation to the scope of the studios and the weekly learning activities to enable critical engagement with the shared body of knowledge in the field of urban design and to further enrich learning experiences. The survey findings suggest that a significant number of respondents (90%) found the selected weekly readings useful in helping them to understand the related urban design aspects and to develop their urban design portfolios. Most students were also satisfied with the overall quality of learning and teaching activities (90%).

Summative assessment and formative feedback, including sessional oral feedback and studio workshops, were the main aspects of assessment and feedback in the urban design studios. The summative assessment of the studios was the assessment of an urban design portfolio (100%—Individual). A rather detailed and structured document called “Assessment Proforma” was developed to provide the related instructions and critical information regarding the assessment type, length, submission, marking criteria, feedback, and format, among others. The Assessment Proforma document enabled a degree of consistency across the 12 parallel studio sections and tutorial groups. During the weekly face-to-face studio tutorials, students were provided with the opportunity to receive sessional oral feedback in relation to their learning progress and overall performance. In addition, two live online studio workshops were designed in each studio so that students could present a copy of their work-in-progress and receive formative feedback from paired studio tutors. The first live online workshop took place in the middle of each design studio and the second one took place towards the end of each studio. Students were paired differently for each studio workshop so that they could receive formative feedback from other paired tutors in addition to their own studio tutors. Of the survey respondents, 90% agreed that studio workshops were helpful in allowing them to engage with presentations by other students and learn from their peers throughout the process. The importance of these studio workshops and the formative feedback received from the paired tutors for enhancing their learning experience and developing their individual urban design portfolios was further highlighted by a significant number of students (about 94%).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The attempt in this paper has been to open up the discussion about “what to teach” and “how to teach” in the context of urban design education with a focus on studio pedagogy. Drawing on empirical research, the paper explained the design and delivery of the two constructively aligned and blended urban design studios as part of the 2021–2022 MAUD programme at Cardiff University, illustrated their relations, and outlined the related learning and teaching activities. It also presented the relevant results of the online survey in relation to the design and delivery of the urban design studios. The findings of this study can provide insights regarding the design and delivery of studio-based modules in urban design and further inform the future development of pedagogical frameworks for designing blended studios. In what follows, a range of identified issues including FSVs, policy review, precedent review, student diversity, and community engagement will be discussed by drawing on the key findings of the study in the context of blended urban design studio teaching and learning. This section will then be followed by outlining some of the limitations of the study and future research directions.

A key finding in this paper indicates that designing two consecutive and constructively aligned design studios (a total of about 20 teaching weeks) can work better in comparison with designing two entirely separate stand-alone design studios engaging with different topics and sites. This is particularly at stake in the context of postgraduate Urban Design programmes in the UK, which typically incorporate a total of one-year full-time postgraduate study. The idea of designing two consecutive design studios supports the argument put forward by Loukaitou-Sideris and Mukhija [

23] according to which a narrow timeframe of 10 weeks has been critiqued for not effectively facilitating the delivery of an urban design studio with time-consuming activities, such as intensive FSVs and rigorously developed design proposals. As such, longer timeframes of 15 weeks or two consecutive 10 weeks are suggested as better alternatives [

23]. Designing the structure of the two constructively aligned urban design studios that were discussed in this paper required a particular focus on the same place and overarching topic as the studio site for the duration of both studios. This also resonates with the idea of focusing on a place (e.g., a corridor or neighbourhood scale area) for the whole semester, as suggested by Macdonald [

13], since it enables deep exploration of the selected area. It also provides individual learners from different educational backgrounds with opportunities to simultaneously develop their graphic presentation skills throughout the process. This can particularly be relevant to one-year full-time postgraduate studies in urban design that admit students without or with limited relevant educational backgrounds and skills.

This paper highlights the value of learning from cities as real urban design laboratories, which is in contrast to the finding that suggests initial FSVs to urban places can be substituted by the availability of fine-grained geospatial data on the built environment of urban regions [

22]. The approach, as discussed in the context of urban design pedagogy in this paper, is largely in line with the idea of exposing students to different insights, which come from spending time in real places rather than merely analysing abstract secondary datasets [

13]. If not treated critically, the aimless and endless use and collection of secondary data can merely produce a data dump and sustain a data-driven approach to teaching and learning urban design, which can also camouflage the difference between data and knowledge. This paper finds that design studios can enable the confrontation of the introduced urban design aspects with reality by accommodating two elements of face-to-face FSVs that take place on different days in relation to the weekly studio tutorials and reading seminars. The ideas and materials discussed as part of the reading seminars and in connection with guest lectures can be confronted with how real places work to encourage a more focused, informed, and engaged approach to the development of an urban design project. It is notable that to integrate FSVs more effectively as an integral part of urban design studio pedagogy, particular attention should be made to the development of relevant criteria for formulating the overall aim and scope of the FSVs in relation to the studio topic. The criteria may incorporate different elements ranging from data richness and physical accessibility to safety and environmental considerations.

The paper posits that urban design studio pedagogy should be concerned with certain learning and teaching activities, which include critical analysis of relevant policies mainly because urban design interventions generally require supportive urban policies. This also relates to the growing policy interest associated with urban design issues, particularly in the context of the UK [

44]. For instance, transit station areas can become walkable if traffic is calmed and transport policies support active modes of travel (e.g., walking, cycling and public transport) over private motorised forms of transportation [

9,

10]. This resonates well with Whitzman’s [

20] argument that it is critical for urban design education to engage with larger metropolitan, national and global strategic planning and governance challenges as localised interventions require supportive metropolitan policy and zoning to effectively contribute to progressive urban change. The policy review in the context of the urban design studios discussed in this paper primarily engaged with the relevant policies and key documents, including the Cardiff Local Development Plan (2006–2026) and Placemaking Wales Guide (2020) in relation to the studio site and context. It is important to note that the development plans in the UK sit at the heart of the planning system. Thus, any design propositions for particular sites or places should be treated within the local authority development plans [

21]. An important finding of this study is that 70% of participants perceived the policy review as helpful for developing their individual portfolios. The inclusion, identification, and review of the locational place-specific vision and the related spatial policies in the context of urban design studio pedagogy are in line with the critical need “for interventions in the design and development processes that reflect the potentially proactive role of the public sector in shaping places” [

45] (p. 40).

The study argues that the inclusion of small group reading discussions needs to be an integral part of the urban design studio pedagogy. They can enable students to become critically engaged with the shared body of knowledge that can effectively inform urban analysis and the development of research-based design projects. This is aligned with the point that knowledge discussion in the context of design studios where design and research are combined can make the process of design education more comprehensive [

46] (p. 151). The findings of this paper suggest that such discussions as part of the reading seminars can enhance peer learning and critical engagement with the shared body of knowledge in the field of urban design. According to the survey results, a significant number of respondents (90%) found the weekly readings useful in supporting them to understand the related urban design aspects and develop their design portfolios. This is also linked to the ways in which they can enable individual learners to more effectively “situate” theories [

15]. According to the findings of this paper, students can also make more informed decisions concerning the development of their design projects as they are provided with opportunities to learn by confronting the discussions of the shared body of knowledge with how places work in reality.

While developing a community engagement framework was among the key learning activities in the urban design studios, there was limited actual engagement with the related communities on the ground due to a range of ethical and professional considerations. As argued in the existing literature, students can undoubtedly benefit from forms of community outreach, engagement, and participation throughout the process of design [

18,

23]. Nevertheless, it is important to critically engage with the questions of how, the extent to which, and for what purposes communities can become involved as part of the urban design studio pedagogy. For one thing, it is critical to note that the sheer size of a postgraduate programme such as the MAUD at Cardiff University with about 100 students can constrain almost any meaningful form of community engagement. Such activities can also become harmful as they are likely to add a burden to local communities and raise their expectations without or with limited scope for delivering real change on the ground. This is mainly because such activities can raise unrealistic expectations among community groups and individuals [

23]. To partly address this gap, several guest lecturers were invited including those with extensive professional practice experience working with the related communities.

Another key finding of the study is related to how different formative feedback opportunities can be designed with a focus on learning and teaching experiences. While the value of formative feedback in higher education has been highlighted in the relevant literature, little is known about the capacities and challenges associated with the provision of different formative feedback opportunities in the context of urban design education and studio pedagogy [

6]. According to the survey results, 90% of respondents agreed that studio workshops were helpful in enabling them to engage with presentations by other students and learn from their peers. As discussed in this paper, in addition to the opportunities provided for students to receive formative feedback as part of their face-to-face weekly studio tutorials, two studio workshops were designed to enable students to receive live online formative feedback from paired studio tutors in each urban design studio. Most respondents (about 94%) also highlighted the significance of the live online studio workshops and the formative feedback provided by the paired tutors for the enhancement of the learning experience and the development of urban design portfolios. Drawing on Schön [

47,

48], the paper argues that opportunities for formative feedback can further enable students to exercise “reflection-in-action” in the context of design studios where students can critically engage with the development of their projects by reflecting on possible consequences of different analytical approaches and design interventions. The findings of this study support the point that the provision of timely formative feedback can enable individual learners to become reflective on their performance as well as their overall learning progress [

49,

50,

51]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that while the provision of formative feedback is much appreciated, its design, organisation, and delivery in the context of a market-driven higher education economy can become quite time-consuming, resource-intensive, and demanding with considerable workload implications that tend to remain largely invisible.

The related admission and recruitment strategies are central to the ways in which learning and teaching urban design play out in the context of higher education. While there is benefit in admitting students from a diverse range of educational backgrounds to reflect the multidisciplinary nature of the field of urban design [

13,

24], the paper argues that in the context of one-year full-time postgraduate programmes in urban design such as the ones in the UK, there might be limited time and/or scope for students from less relevant fields without or with limited relevant skills to develop their urban analysis and design skills to the point that they can most effectively benefit from the variety of learning activities and materials offered in design studios. The paper also supports the idea that having students from diverse national backgrounds in design studios can be helpful in preparing future urban designers for global practice [

24]. Nevertheless, it is critical that the English language skills of the admitted students whose first language is not English enable them to effectively engage with the related learning activities and materials. According to the results of the online survey, only 66.7% of participants agreed that their English language skills enabled them to effectively engage with learning materials and activities in urban design studios. This is also particularly at stake in one-year full-time postgraduate programmes in urban design such as the ones in the UK as there might be limited time and/or scope for students whose first language is not English to develop their English language skills to the point that they can most effectively benefit from the depth and breadth of the related learning activities and materials. Language barriers in the context of design studio pedagogy can pose challenges concerning critical engagement, group activities, reading seminars, tutorial discussions, project communications, workshop presentations, and assessments. It is also important to note that overreliance on recruiting students primarily from certain international markets can run the risk of limiting the possibilities for diversification. The lack of diversity in recruitment and admission strategies has been outlined by Scott and Mhunpiew [

52] as a threat to many higher education institutions, particularly in the context of the UK. Addressing such issues first and foremost requires adopting a critical approach to the admission and recruitment strategies and decision-making processes with a particular focus on the related learning and teaching experiences.