Teacher-Student Reflections: A Critical Conversation about Values and Cultural Awareness in Community Development Work, and Implications for Teaching and Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Statement of the Problem

3. The Context

4. Community Development–A Student and a Teacher’s View

There Are Many Interpretations of Community Development, How Would You Define It?

5. Community Values and Day-to-Day Practice

Why Is It So Important to Take a Value-Driven Approach to Community Development?

6. Cultural Diversity and Community Development

We Live in a Culturally Diverse World, What Helps Community Development Workers to Celebrate This?

7. Critical Pedagogy and Community Development

How Relevant Are Freire’s Ideas in Contemporary Practice?

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freire, P. Letters to Cristina Reflections on My Life and Work; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Community Learning and Development Standards Council for Scotland. Available online: http://cldstandardscouncil.org.uk/resources/values-of-cld/Values of CLD (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lifelong Learning UK. National Occupational Standards for Community Development; Lifelong Learning UK: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kretzmann, J.; McKnight, J. Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets, The Asset-Based Community; Institute for Policy Research: Evanston, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider, D.L.; Whitney, D.; Stavros, J.M. The Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change, 2nd ed.; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alinsky, S.D. Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt, S.B. The Obama Victory, Asset-Based Development and the Re-Politicization of Community Organizing. N. Amer. Dialogue 2008, 11, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

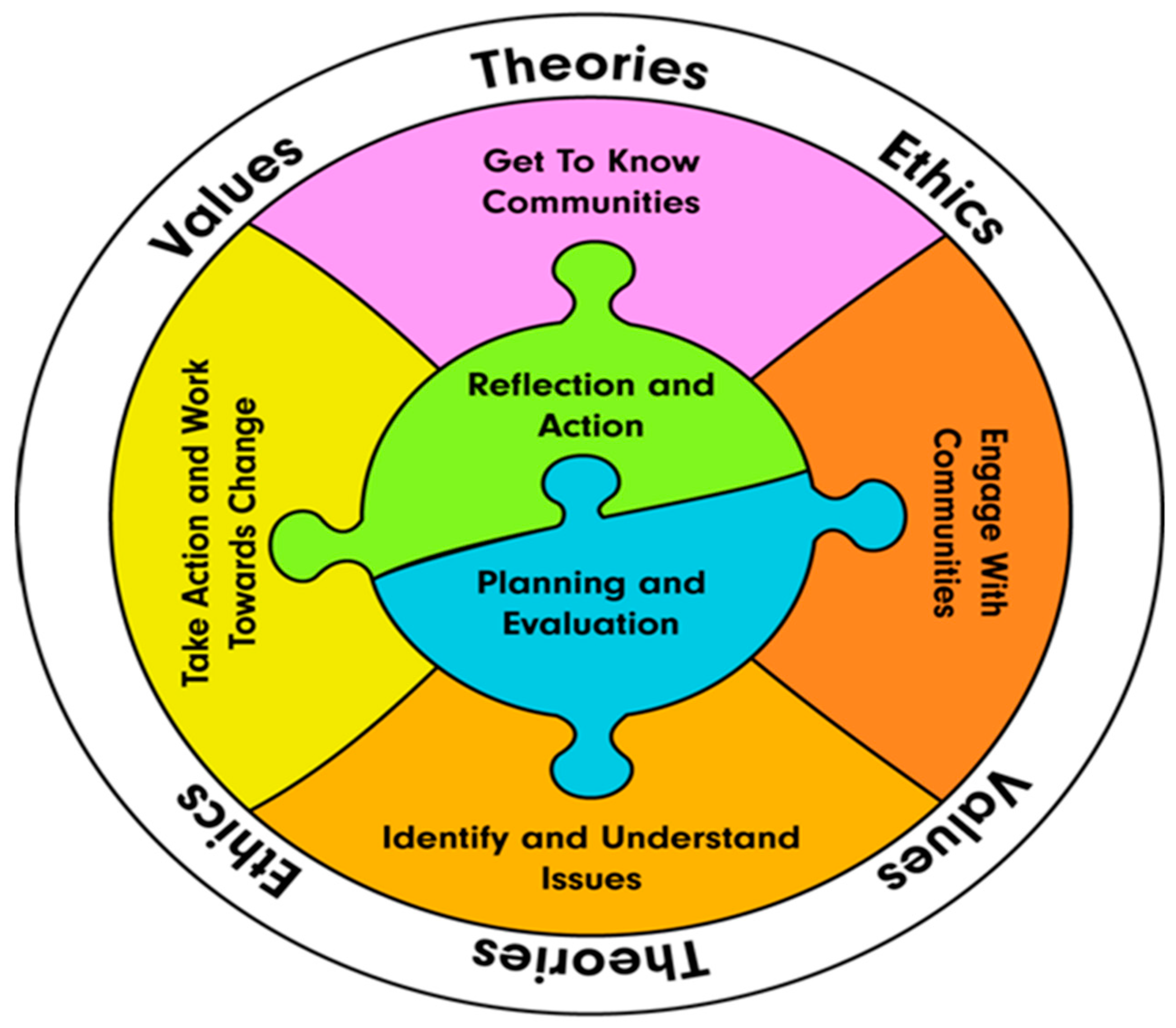

- Sheridan, L.; Martin, H.; McDonald, A. Community Development Jigsaw. In Proceedings of the World Community Development Conference, Dundee, Scotland, 23–30 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eberl, J.-M.; Meltzer, C.E.; Heidenreich, T.; Herrero, B.; Theorin, N.; Lind, F.; Berganza, R.; Boomgaarden, H.G.; Schemer, C.; Strömbäck, J. The European media discourse on immigration and its effects: A literature review. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2018, 42, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilchrist, A. The Well-Connected Community. A Networking Approach to Community Development, 3rd ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, L. Youth Participation in North Ayrshire, Scotland, From a Freirean Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, P. Understanding Community; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, L. Community Development—A Value-Driven Affair. Radic. Community Work. J. 2020, 4, 1–17. Available online: http://www.rcwjournal.org/ojs/index.php/radcw/article/view/79 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Federation for Community Development Learning. Available online: https://www.fcdl.org.uk/ (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Afrane, S.; Naku, D. Local Community Development and the Participatory Planning Approach: A Review of Theory and Practice. Curr. Res. Soc. Sci. 2013, 5, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervedink, N.C. Culturally Sensitive Curriculum Development. In Collaborative Curriculum Design for Sustainable Innovation and Teacher Learning; Pieters, J., Voogt, J., Pareja Roblin, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macrine, S.L. (Ed.) Introduction. In Critical Pedagogy in Uncertain Times Hope and Possibilities; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A. The Attack on Higher Education and the Necessity of Critical Pedagogy. In Critical Pedagogy in Uncertain Times Hope and Possibilities; Macrine, S., Ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S. Freire Re-viewed. Educ. Theory 2007, 57, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boal, A. Theatre of the Oppressed, 7th ed.; Theatre Communications Group: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tuckman, B.W. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol. Bull. 1965, 63, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tuckman, B.W.; Jensen, M.A.C. Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited. Group Organ. Stud. 1977, 2, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronowitz, S. Paulo Freire’s Radical Democratic Humanism: The Fetish of Method. Counterpoints 2012, 422, 257–274. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42981762 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

| Typology of Community Development Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | Equality and Justice | Action for Change | Collective Working | Learning through Life |

| The Community Learning and Development Standards Council for Scotland Values | ||||

| Self-Determination | Inclusion | Empowerment | Working Collaboratively | Promotion of Learning as a Lifelong Activity |

| Respecting the individual and valuing the right of people to make their own choices | Valuing equality of both opportunity and outcome, and challenging discriminatory practice | Increasing the ability of individuals and groups to influence issues that affect them and their communities through individual and/or collective action | Maximising collaborative working relationships in partnerships between the many agencies which contribute to CLD, including collaborative work with participants, learners, and communities | Ensuring that individuals are aware of a range of learning opportunities and can access relevant options at any stage of their life |

| The National Occupational Standards for Community Development Values | ||||

| Equality and Anti-Discrimination | Community Empowerment | Working and Learning Together | ||

| Community development practitioners will work with communities and organisations to challenge the oppression and exclusion of individuals and groups | Community development practitioners will work with communities and organisations to work together | Community development practitioners will support individuals and communities working and learning together | ||

| Social Justice | Collective Action | |||

| Community development practitioners will work with communities and organisations to achieve change and the long-term goal of a more equal, non-sectarian society | Community development practitioners will work with communities to organise, influence and take action | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheridan, L.; Mungai, M. Teacher-Student Reflections: A Critical Conversation about Values and Cultural Awareness in Community Development Work, and Implications for Teaching and Practice. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090526

Sheridan L, Mungai M. Teacher-Student Reflections: A Critical Conversation about Values and Cultural Awareness in Community Development Work, and Implications for Teaching and Practice. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):526. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090526

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheridan, Louise, and Matthew Mungai. 2021. "Teacher-Student Reflections: A Critical Conversation about Values and Cultural Awareness in Community Development Work, and Implications for Teaching and Practice" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090526

APA StyleSheridan, L., & Mungai, M. (2021). Teacher-Student Reflections: A Critical Conversation about Values and Cultural Awareness in Community Development Work, and Implications for Teaching and Practice. Education Sciences, 11(9), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090526