Educational Programs to Build Resilience in Children, Adolescent or Youth with Disease or Disability: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Concept of Resilience

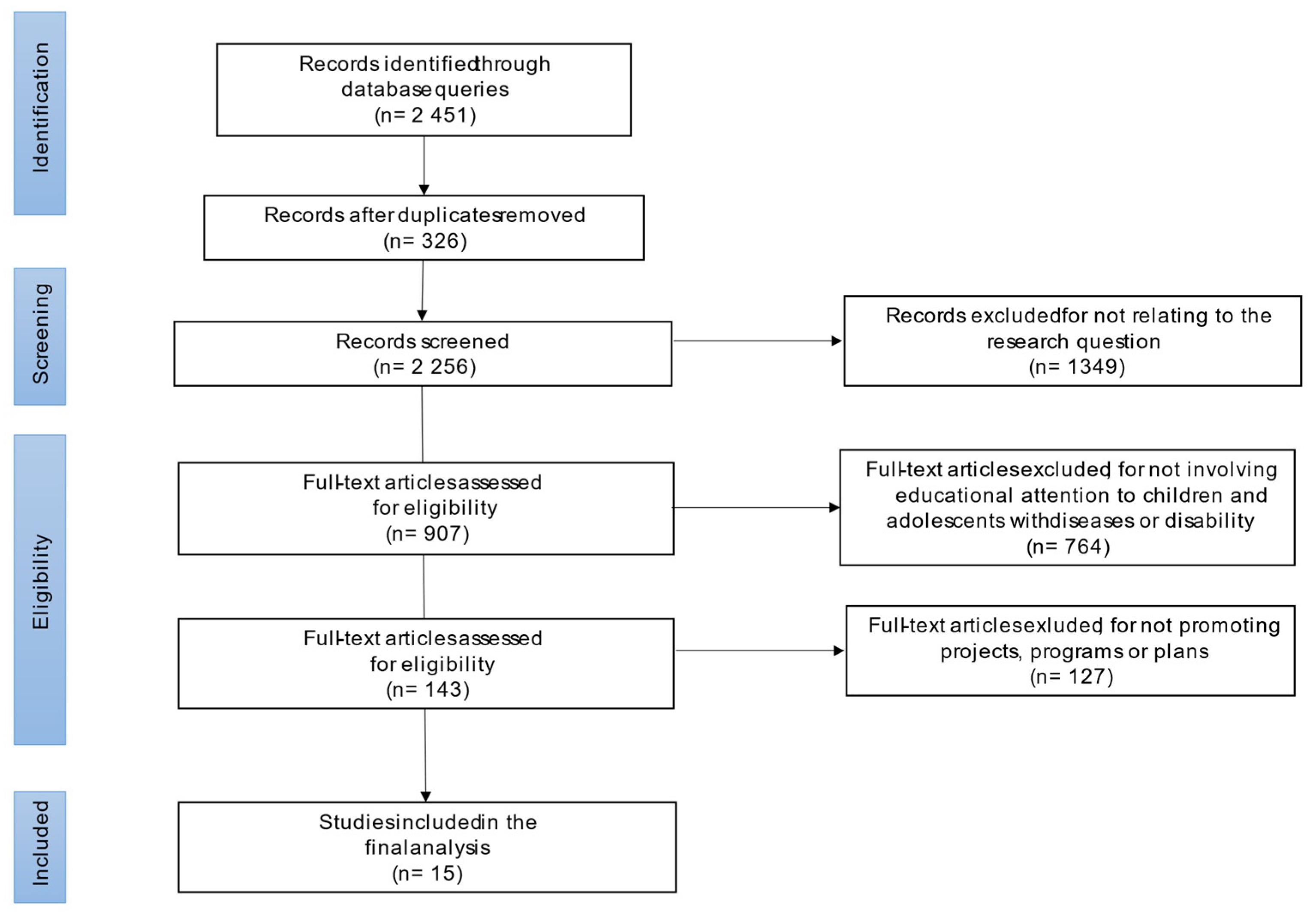

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Analysis Using VOSviewers

2.3. Analytical Produce

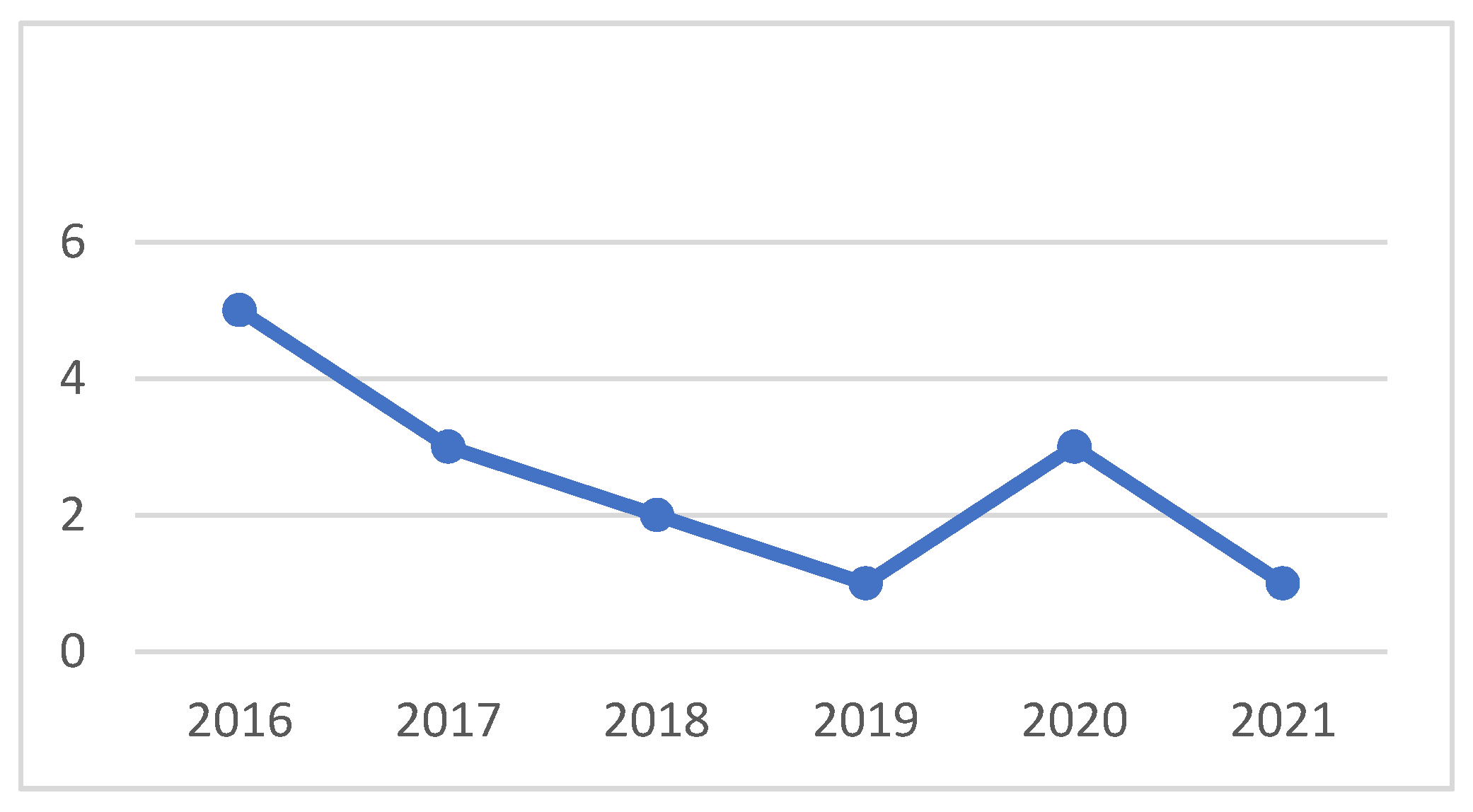

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manciaux, M. La Resiliencia: Resistir y Rehacerse; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Windle, G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2011, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. The social ecology of resilience: Addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, J.S.; Walsh, F. Facilitating family resilience with childhood illness and disability. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2006, 18, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Strengthening Family Resilience, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson Grotberg, E. La Resiliencia en el Mundo de Hoy. Cómo Superar Las Adversidades; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Forés Miravalles, A.; Grané Ortega, J. La Resiliencia en Entornos Socioeducativos; Narcea S.A. De Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barankin, T.; Khanlou, N. Growing Up Resilient: Ways to Build Resilience in Children and Youth; Centre for Addition and Mental Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Puig, G.; Rubio, J.L. Manual de Resiliencia Aplicada; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience in developing systems: The promise of integrated approaches. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Rractice; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy, N. Resiliency and Vulnerability to Adverse Developmental Outcomes Associated With Poverty. Am. Behav. Sci. 1991, 34, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. NIH Public Access 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E.E. Risk, resilience, and recovery: Perspectives from the Kauai Longitudinal Study. Dev. Psychopathol. 1993, 5, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.; Goldstein, S. The Power of Resilience; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, J.S.; Walsh, F. Systemic Training for Healthcare Professionals: The Chicago Center for Family Health Approach. Fam. Process 2005, 44, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, F. Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. Systemic resilience: Principles and processes for a science of change in contexts of adversity. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barudy, J.; Dantagnan, M. Los Buenos Tratos a la Infancia; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vanistendael, S.; Lecomte, J. La Felicidad es Posible. Despertar en Niños Maltratados la Confianza en sí Mismos: Construir la Resiliencia; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cyrulnik, B.; Capdevila, C. Diálogos. Cyrulnik y Capdevila; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, C. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination; SAGE: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Manchado Garabito, R.; Tamames Gómez, S.; López González, M.; Mohedano Macías, L.; D’Agostino, M.; Veiga de Cabo, J. Revisiones Sistemáticas Exploratorias. Med. Segur. Trab. 2009, 55, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codina, L. Revisiones Bibliográficas Sistematizadas. Procedimientos Generales y Framework para Ciencias Humanas y Sociales; Universitat Pompeu Fabra: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal Dutta, R.; Salamon, K.S. Risk and Resilience Factors Impacting Treatment Compliance and Functional Impairment among Adolescents Participating in an Outpatient Interdisciplinary Pediatric Chronic Pain Management Program. Children 2020, 7, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L.L.; Desson, S.; St John, E.; Watt, E. The D.R.E.A.M. program: Developing resilience through emotions, attitudes, & meaning (gifted edition)—A second wave positive psychology approach. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2019, 32, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera Mares, S.A.; Acle Tomasini, G.; Martínez Basurto, L.M. Modelo ecosistémico de riesgo/resiliencia: Validez social de un programa para niños con problemas de lenguaje. In Psicología y Educación: Presente y Futuro, 1st ed.; Castejón Costa, J.L., Ed.; ACIPE: Alicante, Spain, 2016; pp. 2198–2207. [Google Scholar]

- Cantero-García, M.; Garrido-Hernansaiz, H.; Alonso-Tapia, J. Diseño del programa de apoyo psicoeducativo para promover la resiliencia parental “Supérate. ¡No tires la toalla!”. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 18, 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, J.; Bowman, J.; Campbell, E.; Freund, M.; Hodder, R.; Wolfenden, L.; Richards, J.; Leane, C.; Green, S.; Lecathelinais, C.; et al. Effectiveness of a pragmatic school-based universal intervention targeting student resilience protective factors in reducing mental health problems in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2017, 57, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.K.; Bungay, V.; Patterson, A.; Saewyc, E.M.; Johnson, J.L. Assessing the impacts and outcomes of youth driven mental health promotion: A mixed-methods assessment of the Social Networking Action for Resilience study. J. Adolesc. 2018, 67, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Harrison, S.E.; Fairchild, A.J.; Chi, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, G. A randomized controlled trial of a resilience-based intervention on psychosocial well-being of children affected by HIV/AIDS: Effects at 6- and 12-month follow-up. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 190, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morote, R.; Las Hayas, C.; Izco-Basurko, I.; Anyan, F.; Fullaondo, A.; Donisi, V.; Zwiefka, A.; Gudmundsdottir, D.G.; Ledertoug, M.M.; Olafsdottir, A.S.; et al. Co-creation and regional adaptation of a resilience-based universal whole-school program in five European regions. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Garrido, V. La resiliencia: Una intervención educativa en pedagogía hospitalaria. Rev. Educ. Inclusiva 2016, 9, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Quinteros, L.E. La resiliencia en estudiantes con Déficit Atencional por Hiperactividad. Rev. Int. Apoyo Incl. Logop. Soc. Multicult. 2018, 4, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascón Gómez, M.T.; Cabello Fernández-Delgado, F. Narrativas audiovisuales sobre resiliencia y educación desde un enfoque edu-comunicativo. Innov. Educ. 2019, 19, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, J.G.; Phiri, L.; Chibuye, M.; Namukonda, E.S.; Mbizvo, M.T.; Kayeyi, N. Integrated psychosocial, economic strengthening, and clinical service-delivery to improve health and resilience of adolescents living with HIV and their caregivers: Findings from a prospective cohort study in Zambia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, W.R. The FOCUS Family Resilience Program: An Innovative Family Intervention for Trauma and Loss. Fam. Process 2016, 55, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, Ó.; Méndez Carrillo, F.X.; Garber, J. Promoting resilience in children with depressive symptoms | Promoción de la resiliencia en niños con sintomatología depresiva. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saul, J.; Simon, W. Building Resilience in Families, Communities, and Organizations: A Training Program in Global Mental Health and Psychosocial Support. Fam. Process 2016, 55, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee on Standards for Educational Evaluation. Standards for Evaluations of Educational Programs, Projects, and Materials; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov, C.J. Training to Think Culturally: A Multidimensional Comparative Framework. Fam. Process 1995, 34, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau Rubio, C. Fomentar la resiliencia en familias con enfermedades crónicas pedriátricas. Rev. Española Discapac. 2013, 1, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosselló, M.R.; Verger, S.; Negre, F.; Lourido, B.P. Interdisciplinary care for children with rare diseases. Nurs. Care Open Access J. 2018, 5, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boingboing. Resilience Framework (Children & Young People), October 2012—Adapted from Hart & Blincow 2007 [Internet]. 2012. Available online: https://www.boingboing.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/resilience-framework-children-and-young-people-2012-spanish-final.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2019).

| Keywords | DeCS | ERIC Thesaurus |

|---|---|---|

| Resilience | Resilience, Psychological | Resilience (Psychology) Resilience (Academic) |

| Program/Intervention/Plan | Programs | Programs |

| Database | Search Equations | Date | Records |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | ((resilienc*) AND (program * OR plan * OR intervention OR strategy *)) | 12 February 2021 | 421 |

| WoS | ((resilienc*) AND (program * OR plan * OR intervention OR strategy *)) | 12 February 2021 | 810 |

| EBSCOhost | ((resilienc *) AND (interventions or strategies or best practices) AND (interdisciplinary)) | 13 February 2021 | 475 |

| ERIC | resilience AND (programs OR strategy OR plan OR intervention) | 13 February 2021 | 102 |

| Dialnet Plus | ((resilienc *) AND (program * OR plan * OR intervention OR strategy *)) | 15 February 2021 | 643 |

| Database | Year | Journal | Authors | Program | Method | Country | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WoS | 2020 | Children | Aggarwal, R. Salamon, K.S. | Outpatient Interdisciplinary Pediatric Chronic Pain Management Program [29] | QT | USA | EN |

| EBSCOhost | 2019 | Counselling Psychology Quarterly | Armstrong, L.L. Desson, S. St. John, E. Watt, E. | D.R.E.A.M. Program [30] | MM | Canada | EN |

| Dialnet Plus | 2016 | Psicología y Educación: Presente y Futuro | Barrera, S.A. Acle, G. Martínez, L.M. | Program for children with language difficulties with the risk/resilience ecosystem model: [31] | QT | Mexico | SP |

| Scopus | 2020 | Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology | Cantero-García, M. Garrido-Hernansaiz, H. Alonso-Tapia, J. | “Supérate. ¡No tires la toalla!” Program [32] | QL | Spain | SP |

| WoS | 2017 | Journal of Adolescence | Dray, J. Bowman, J. Campbell, E. Freund, M. Hodder, R. Wolfenden, L. Richards, J. Leane, C. Green, S. Lecathelinais, C. Oldmeadow, C. Attia, J. Gillham, K. Wiggers, J. | Pragmatic school-based universal intervention [33] | QT | Australia | EN |

| Scopus | 2018 | Journal of Adolescence | Jenkins, E.K. Bungay, V. Patterson, A. Saewyc, E.M. Johnson, J.L. | Social Networking Action for Resilience (SONAR) study [34] | MM | Canada | EN |

| WoS | 2017 | Social Science and Medicine | Li, X. Harrison, S.E. Fairchild, A.J. Chi, P. Zhao, J. Zhao, G. | Child-Caregiver-Advocacy Resilience (ChildCARE) intervention [35] | QT | USA China | EN |

| Scopus | 2020 | European Educational Research Journal | Morote, R. Las Hayas, C. Izco-Basurko, I. Anyan, F. Fullaondo, A. Donisi, V. Zwiefka, A. Gudrun, D. Ledertoug, M.M. Olafsdottir, A.S. Gabrielli, S. Carbone, S. Mazur, I. Królicka-Deręgowska, A. Henrik Knoop, H. Tange, N. Kaldalóns, I. Jónsdóttir, B. González Pinto, A. Hjemdal, O. | UPRIGHT (Universal Preventive Resilience Intervention Globally implemented in schools to improve and promote mental Health for Teenagers) [36] | MM | Spain Italy Poland Denmark Iceland | EN |

| WoS | 2016 | Revista de Educación Inclusiva Inclusive Education Journal | Muñoz Garrido, V. | Hospital classroom at the CPEE Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid [37] | QL | Spain | SP |

| ERIC | 2017 | Revista Internacional de Apoyo a la Inclusión, Logopedia, Sociedad y Multiculturalidad | Pérez Quinteros, L.E. | Proyecto Ángel [38] | MM | Chile | SP |

| WoS | 2019 | Innovación Educativa | Rascón, M.T. Cabello, F. | Educational innovation project: Multimedia perspectives on resilience and education [39] | MM | Spain | SP |

| WoS | 2021 | PLoS ONE | Rosen, J.G. Phiri, L. Chibuye, M. Namukonda, E.S. Mbizvo, M.T. Kayeyi, N. | Zambia Family (ZAMFAM) Project [40] | QT | Zambia | EN |

| Scopus | 2016 | Family Process | Saltzman, W.R. | FOCUS Program [41] | QL | USA | EN |

| WoS | 2016 | Anales de Psicología | Sánchez-Hernández, Ó. Méndez Carrillo, F.X. Garber, J. | Penn Resiliency Program [42] | MM | Spain | EN |

| Scopus | 2016 | Family Process | Saul, J. Simon, W. | Summer Institute in Global Mental Health and Psychosocial Support [43] | QL | USA The Netherlands | EN |

| Reference | Program | Objective | Participants | Design | Intervention | Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggarwal and Salamon [29] | Outpatient Interdisciplinary Pediatric Chronic Pain Management Program | Explore the risk and resilience factors that contribute to treatment compliance and functional decline among youth with chronic pain during adolescence. | 64 adolescents (11–18 years old) diagnosed with chronic pain from a children’s hospital located in the northeastern region of the USA. | Quasi-experimental study | Psychological interventions based on Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with 6–10 sessions for pain and stress management. | Several questionnaires. | Findings indicate that adolescent resilience factors (i.e., high pain self-efficacy, high pain acceptance) may make adolescents less likely to comply with treatment overall. |

| Armstrong et al. [30]. | D.R.E.A.M. Program | The D.R.E.A.M. (Developing Resilience through Emotions, Attitudes, and Meaning) program, grounded in a Second Wave Positive Psychology approach called R.E.A.L. (Rational Emotive Attachment Logotherapy). | 45 children, 6–12 years old, who are affiliated with the Association for Bright Children (ABC) Ottawa. | Quasi-experimental study based on Knowledge Translation-Integrated (KTI) model. | Educational interventions based on Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). | Evaluation with standards of acceptability, feasibility, sustainability, and credibility [44] | A positive self-perception, a sense of hope for the future, and an openness to learning and experiencing new things were the goals of the program. |

| Barrera et al. [31] | Program for children with language difficulties | Program based on risk/resilience ecosystem model for children with oral and written language difficulties. | 6 children with oral and written language difficulties between 6 and 7 years old, his parents and two teachers. | Quasi-experimental study | Educational interventions. | 4 stages: pretest, intervention, social validation and pretest-postest assessment | This work emphasizes effectiveness of risk/resilience ecosystem model in the field of Special Education. |

| Cantero-García et al. [32] | “Supérate. ¡No tires la toalla!” Program | Promote families’ ability to deal with behavioral issues, as well as conflict methods and parents’ emotional regulation levels | 61 parents from 7 Secondary schools in Madrid; 41 in experimental group and 20 in control group. | Non-randomized study | Psychological interventions | Several questionnaires to evaluate various items of this program (learning, transfer, impact, and perception of quality). | The program produced a significant reduction in the levels of anxiety, depression as well as an improvement in the perceived family climate. |

| Dray et al. [33] | Pragmatic school-based universal intervention | Evaluate the efficacy of a universal, school-based intervention focusing on resilience protective variables in reducing mental health problems in adolescents. | 32 secondary schools within a socio-economically disadvantaged (students aged 12–16 years) in the Hunter New England region of New South Wales (NSW), Australia. | Cluster randomized controlled trial | Universal school-based intervention. | Questionnaires to measure mental health and internal and external factors of resilience in students. Additionally, structured interviews to school staff. | Study strengths include a wide range of implementation support strategies, a significant focus on increasing student resilience, and a large sample size. |

| Jenkins et al. [34] | Social Networking Action for Resilience (SONAR) study | Design a mental health promotion intervention based on experience of young people. | 10 youth co-researchers (YCRs) and 344 students enrolled in one Secondary School (grades 8 to 12) of a rural community, located in North-Central British Columbia, Canada | Experimental Study based on Community-based Knowledge Translation (CBKT) framework. | Mental health promotion interventions | Mixed methods approach (both surveys and qualitative interviews) | The SONAR intervention shows the feasibility of involving youth in mental health promotion as well as a variety of positive youth development benefits connected with this collaborative strategy. |

| Li et al. [35] | Child-Caregiver-Advocacy Resilience (ChildCARE) intervention | Promote resilience in HIV/AIDS people in rural central China by educating them skills such as positive thinking, emotional regulation, coping, and problem solving. | 790 Chinese children (6–17 years old) who had a biological father with HIV/AIDS. Children with HIV infection were excluded. | Cluster randomization-controlled trial | Educational and psychological interventions | Questionnaires at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months that included demographic and psychosocial scales. | The ChildCARE intervention is efficacious in promoting psychosocial well-being of children affected by parental HIV/AIDS in rural China. |

| Morote et al. [36] | UPRIGHT (Universal Preventive Resilience Intervention Globally implemented in schools to promote mental Health for Teenagers) | Promote mental well-being by enhancing resilience capacities in young people | 448 Adolescents between 12 and 14 years old, 345 family members and 218 school staff and teachers from several schools in Italy, Denmark, Spain, Poland, and Iceland | Mixed-methods research process combining a survey study with participatory group sessions customized | Educational interventions. | Participatory sessions, survey quantitative and survey qualitative | The participants agreed that in a universal and inclusive program, each member of the school community has a concrete role in fostering resilience and well-being for all. |

| Muñoz Garrido [37] | Hospital classroom at the CPEE Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid | Analysis of the program based on resilience in the hospital classroom | School unit at the Gregorio Marañón Hospital, to care for children admitted for poliomyelitis. | Descriptive and interpretative-symbolic study | Educational interventions. | Satisfaction survey | Students will be more motivated if their teachers provide them with an appropriate learning environment, including techniques, methodology, and humanism. |

| Pérez Quinteros [38] | Proyecto Ángel | Analyze whether there are any strategies that favor the development of resilience in students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). | Students with ADHD of the second level of Basic General Education who participated in a local service project called “Angel Project” in Chile. | Action-research study framed in an interpretative paradigm | Educational and psychological interventions | Mixed methods (participant observation, interviews, a group discussion, and a Likert scale) | Strategies that build resilience refer to enhancement of self-esteem in collaborative work, and development of communication skills and emotional expression. |

| Rascón and Cabello [39] | Multimedia perspectives on resilience and education project | Improve the resilience of children and youth in vulnerable situations | 268 university students and Children and youth in vulnerable situations in Malaga (Spain). | Project-based cooperative learning and Service-learning | Socio-educational interventions | Qualitative evaluations | 77 audiovisual pieces were created for 27 partnering entities in the process of resilience and inclusion of vulnerable groups. |

| Rosen et al. [40] | Zambia Family (ZAMFAM) Project | Strengthening the household’s capacity to meet the needs of people living with or affected by HIV, as well as improving the well-being of the child and caregivers. | 544 Adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) aged 5–17 years and their adult caregivers in Zambia | Prospective cohort study | Multilevel interventions (education, psychosocial, economic, and clinical services) | Structured interviews and Poisson regression with generalized estimating equations measured one-year changes | Significant improvements in caregivers’ financial capacity were observed among house- holds receiving ZAMFAM services, with few changes in health or wellbeing among ALHIV. |

| Saltzman [41] | FOCUS Program | Promote family resilience through communication and make sense of traumatic experiences. | Families exposed to significant levels of stress or loss who may be at risk for psychological disturbance | Longitudinal study | Psychoeducational interventions focused on families | Mixed methods | A structured family approach, creating shared goals, strengthening communication, and practicing specific skills that promote family resilience. |

| Sánchez-Hernández, et al. [42] | Penn Resiliency Program | Study the effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral intervention inspired by the Penn Resiliency Program for the prevention of depression in students from primary education. | 25 students, 10–12 years old, selected from 185 schoolchildren in grades 5 and 6 of Primary education. | Randomized experimental study. Participants were randomly assigned to the experimental group (preventive intervention) and control (waiting list | Cognitive-behavioral interventions. | A mixed 2 × 2 factorial design with an inter factor (prevention program; waiting list) and an intra factor (pretest, posttest). | Results indicated that there was significant improvement from pre-test to post-test in the experimental group for children with “high depressive symptoms” compared with controls. |

| Saul and Simon [43] | Summer Institute in Global Mental Health and Psychosocial Support | Strengthening the capacity of families, communities, and organizations to address mental health issues and promote psychosocial well-being. | 24 professionals (several mental health professionals, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a human rights practitioner, and an ethnomusicologist) | Randomized experimental study | Training program with educational, psychosocial, and health interventions | Qualitative interpretation of experience in the Summer Institute | The Summer Institute provided training to promote a systems-oriented resilience approach in the field of Global Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (GMHPSS) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Parra, M.; Negre, F.; Verger, S. Educational Programs to Build Resilience in Children, Adolescent or Youth with Disease or Disability: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090464

García-Parra M, Negre F, Verger S. Educational Programs to Build Resilience in Children, Adolescent or Youth with Disease or Disability: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090464

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Parra, Martín, Francisca Negre, and Sebastià Verger. 2021. "Educational Programs to Build Resilience in Children, Adolescent or Youth with Disease or Disability: A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090464

APA StyleGarcía-Parra, M., Negre, F., & Verger, S. (2021). Educational Programs to Build Resilience in Children, Adolescent or Youth with Disease or Disability: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 11(9), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090464