Delivering Music Education Training for Non-Specialist Teachers through Effective Partnership: A Kodály-Inspired Intervention to Improve Young Children’s Development Outcomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background to the Kodály Approach

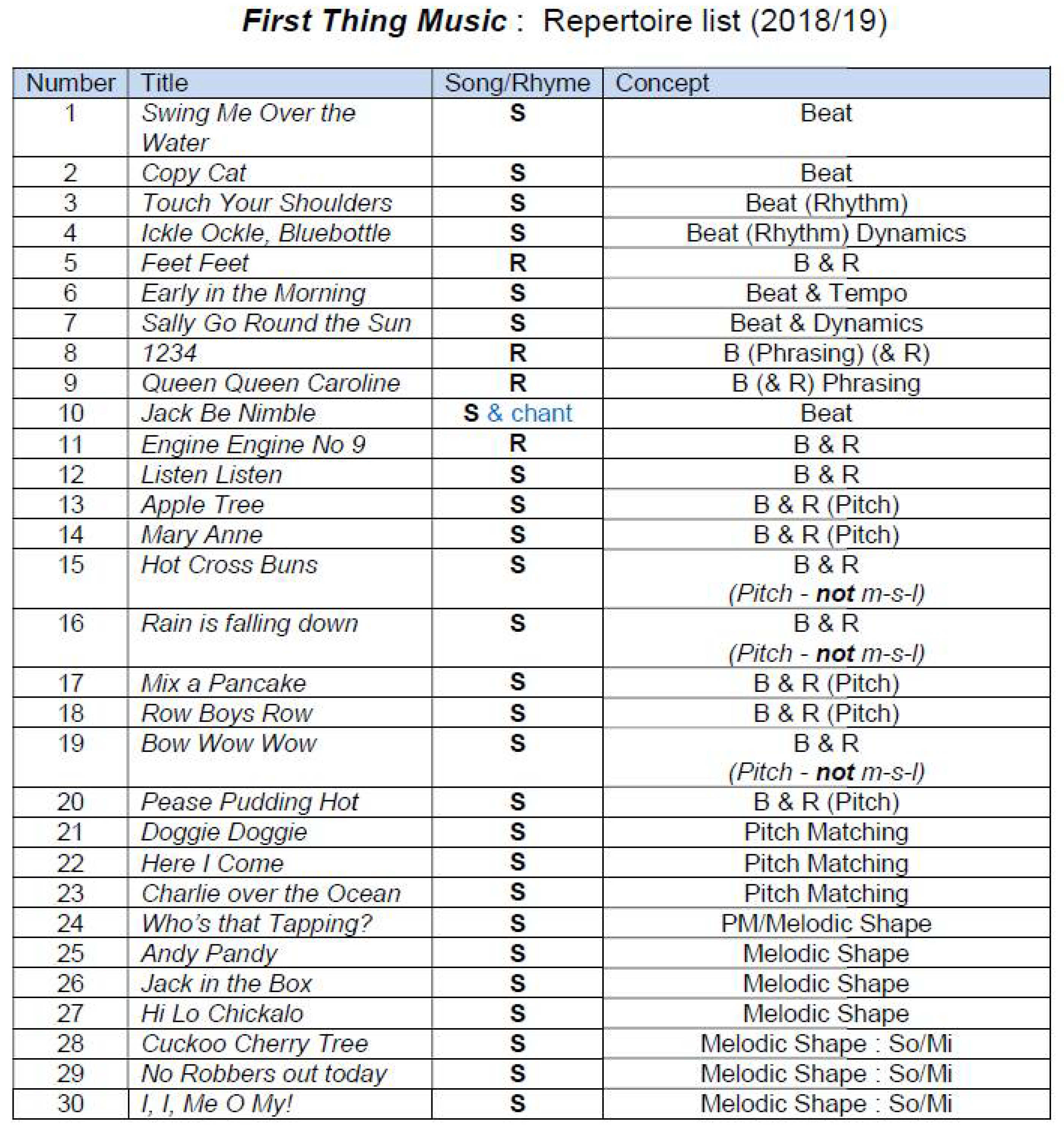

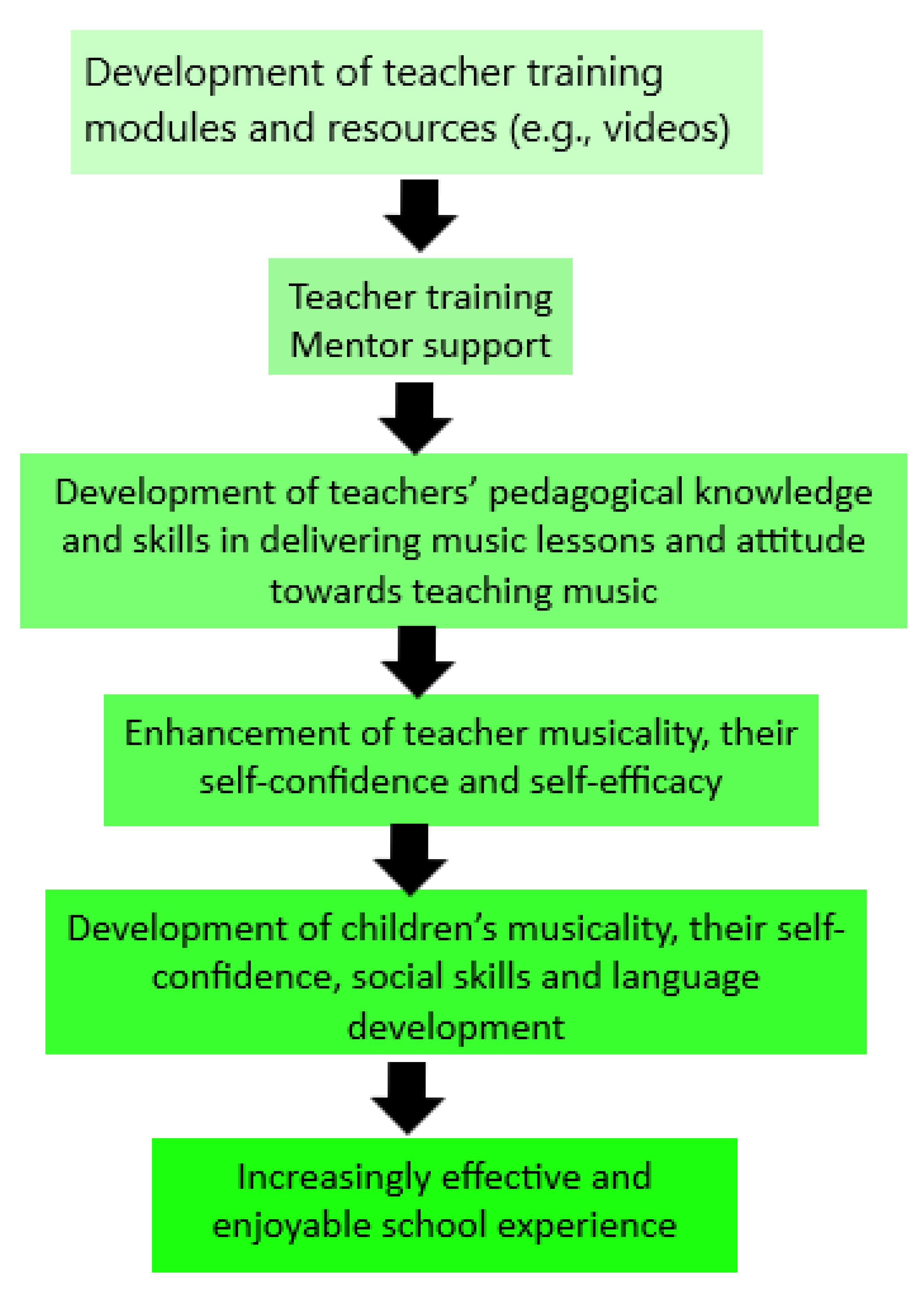

3. The Model of Teacher Training Delivery

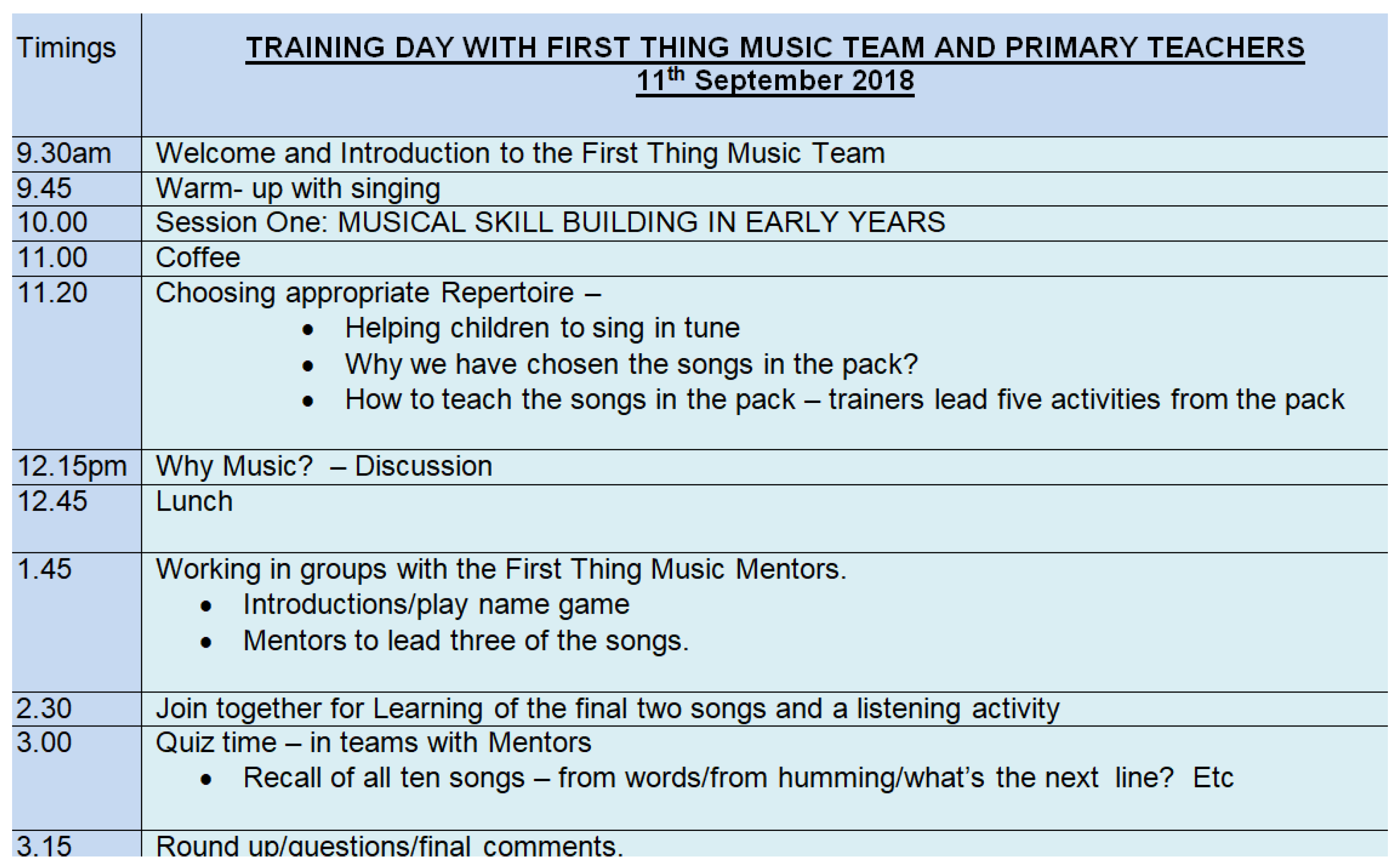

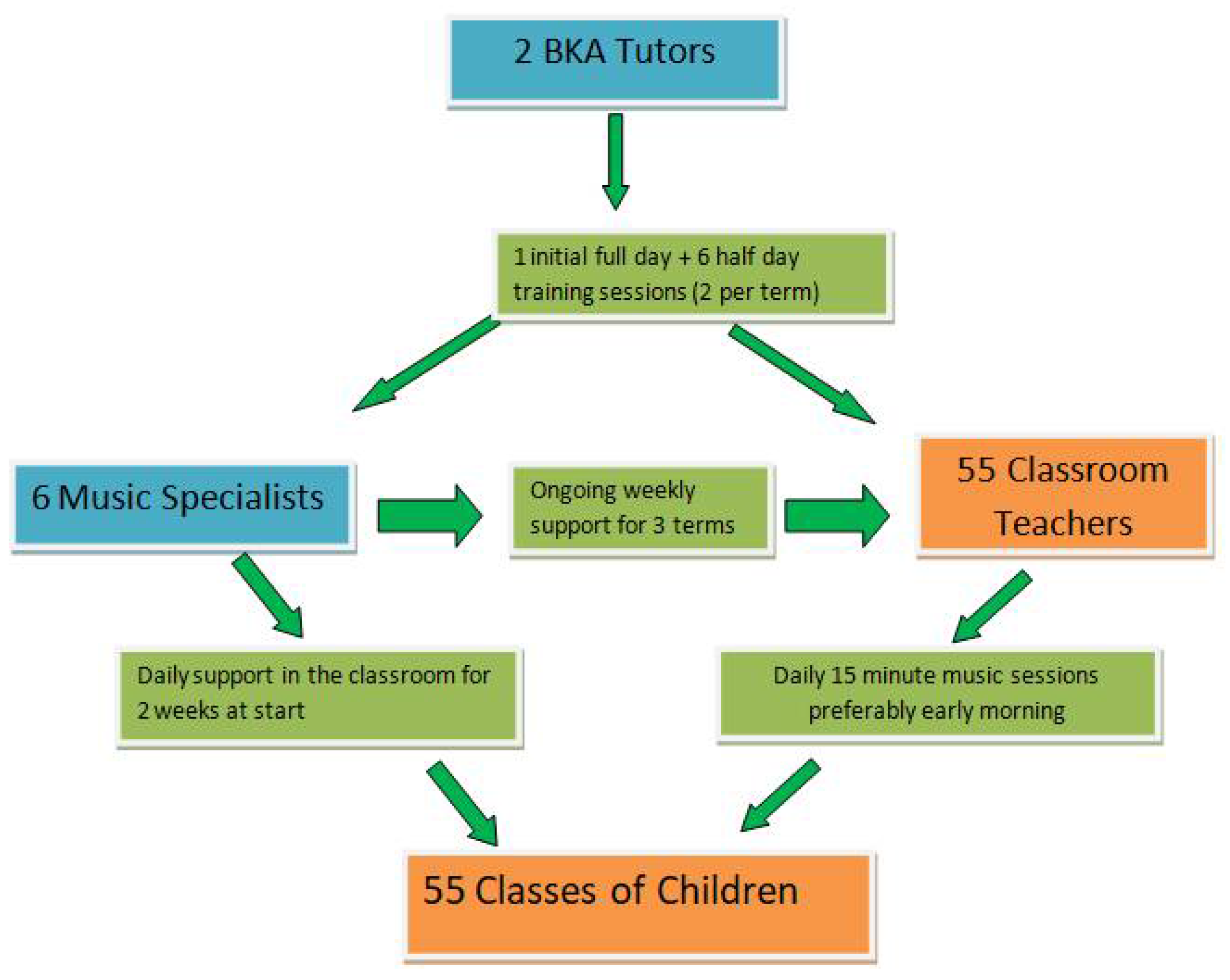

Training of Teachers

- Making beat conscious;

- Experiencing rhythm;

- Making rhythm conscious and how to physically represent and visualise this, leading to analogical notation, (e.g., 1 large figure for a quarter note/crotchet and 2 smaller co-joined figures for eighth notes/quavers);

- Pitch matching—singing in tune;

- Pitch shape and melodic contour—introducing simple pitch notation.

4. Aims

- How feasible is a collaborative partnership with music specialists in delivering Kodály-inspired music training to generalist teachers?

- Does this kind of training appeal to schools, teachers and trainers?

- What are the challenges and barriers to delivering this model of training?

- To what extent is the Kodály-inspired approach to training associated with improvement in teachers’ confidence and competence in delivery of music sessions and their attitude towards music?

- What is the perceived impact on young children’s learning and developmental outcomes?

5. Method

6. Findings

6.1. Is the Collaborative Partnership with Music Specialists a Feasible Approach to Delivering Music Training?

6.2. What Do Teachers, Schools and Trainers Think of the Collaborative Kodály-Inspired Approach to Training?

6.3. What Are the Challenges and Barriers to Delivering This Model of Training?

6.4. Is There Any Relationship Between Training and Teacher Outcomes

6.4.1. Development of Teacher Musicality

I was a bit apprehensive at first, but actually I think I was just over-thinking it.Journal Teacher 1

The project has inspired non-musical teachers to feel confident to deliver music within their settings which is a huge positive for the world of primary education. Having taken part in theFirst Thing Musicproject, I would highly recommend this approach to be used within schools, enabling all children to see themselves as ‘musicians’ regardless of ability and experience.Journal Teacher 7

Some teachers quite reluctant in the warm-up–“I can’t do this”; I don’t know what I’m doing!” or shy when stamping or jumping–little enthusiasm. This tended to ease when teachers worked together more, e.g., when pairing up and trying to ‘break record’, or working on ‘Queen Queen Caroline’ in a group.Enjoying the training, laughing, smiling at mistakes; becoming more confidence as training continues.

6.4.2. Development of Teachers’ Music Practice in the Classroom

Over the course of the First Thing Music project, I feel that I have developed my own skills in teaching and inspiring a love and understanding of Music education and how it can be taught through a process which is joyful and fun for the children. I believe strongly that the children in my class have come on a journey with me which has helped us to develop a secure grounding in life long, transferable musical skills.Journal Teacher 5

A stave of music appeared on the screen with traditional graphic notation and I could hear it clearly inside my head! I learnt to read graphic notation, in the traditional way as a child when learning to play the violin. During this process I was never encouraged to imagine what the music would sound like in my head, before “squeaking” it out on my instrument. This flash of inspiration made it clear how the Kodály(-inspired) method/approach prepares the learner for actually reading music, like we learn to read texts.Journal Teacher 2

Seeing the development in the class teachers, some from a quiet and unsecure place to now leading and writing an end of year sharing story involving many of the singing games—just fabulous!Mentor M

Week 1: What have I been signed up for? I am not a musical person and I have spent a whole day this week singing. I don’t know where to start. I am so pleased that we have a mentor coming in for a week so that she can show me what I actually need to do.Week2: This doesn’t seem so bad after all. I’m not sure I see where this is going, but I can deliver it to the children and they really enjoy doing music every morning. The focus is on the steady beat and some of them are really getting it.Week 22: Mentor came in this week–It’s now got to the point where I feel like we are just showing her what we have been up to. I feel much more confident singing in front of all of the children and even our mentor coming in doesn’t bother me anymore. I’ve come to a realisation that I enjoy singing with the children and it doesn’t matter if I am pitch-perfect, they just laugh it off with me. They love singing and now I actually love singing.Week 30: I introduced ‘Charlie over the ocean’ to the children today and the pure delight in their faces was lovely to see. I found that my foot was keeping the beat and when I discussed this with the children, they could explain to me exactly what I was doing. It’s amazing to think that they have come so far since September with the language they not only know but understand. It isn’t only the children that have come so far; I feel like my understanding of how to teach early music and my passion to do so has improved also.Journal Teacher 1

As a teacher, I believe I have covered the music curriculum in greater depth this year. The support from my mentor, and the training sessions have given me the confidence and the vocabulary to ensure clear progression has been made, and the children are not only achieving, but are completely engaged in their learning. I hope to continue to use my training in subsequent years to ensure effective music teaching.The range of ability in the cohort is vast, with some children working well below age related expectation. However, this intervention provided appropriate challenge and support for all involved. It was amazing to see that specific children who are working at EYFS level are able to access the same lesson as their peers, with one child in particular excelling and becoming one of the more able in music.Journal Teacher 13, Male

The programme has been inspirational to myself, as a Year 1 teacher and my Teaching Assistant—both with a lack of musical ability. It has also been extremely encouraging when other members of staff pass on comments when working with the class, regarding their good listening skills, confidence, timing, good behaviour and positive attitude. I must also mention that the support given during the half termly sessions with the research team and the regular mentor support visits to school helped to alleviate my apprehension with delivering the programme.Journal Teacher 4

I felt very under-confident and reluctant at the beginning of the process, and actually fely [sic] disappointed that my colleague hadn’t been chosen for the project—now I’m going to lead Kodály sessions for all of KS1 next year.Journal Teacher 3

I have observed both classes in a session which I found very exciting. All children were on task and both members of staff delivered the sessions with confidence.Headteacher 2

6.4.3. Teachers’ Attitudes to Teaching Music

We’ve thoroughly enjoyed our singing this term and are looking forward to more in the new year.Written feedback Teacher 4

This is, without a doubt, my favourite part of the day. And what’s even better is that it’s the children’s favourite part too. It’s so nice to see the children learn through play, as they should, without numbers and targets to reach.Journal Teacher 8

6.4.4. Teachers’ Perception of Music in the Curriculum

First Thing Music has certainly given me a passion for music and teaching early music I never imagined I’d have.Journal Teacher 1

I can see that the children are really enjoying the sessions and they were fun for me to join in with them—think they enjoyed that too. I have also noticed that the children are growing in confidence when singing both together and individually and skills like their rhythm and pulse are also improving. I am a huge believer in the impact of music/song/rhythm on other areas of the curriculum and a child’s development.Headteacher 3

I have really enjoyed participating in the First thing music over this term. This is something we used to do a lot of a few years ago and reminded me of some of our key music practice we’ve had in the past that we need to revisit and on a more regular basis—we are looking at this.Headteacher 3

Having attended a session this term I feel the following sums up my opinions:The sessions are well planned and engagingChildren are actively engaged despite any barrier they present, e.g., EAL (English as an additional language), SEND, (special educational needs), or behavioural issuesThe opportunities for rhythm and patterns including dynamics are ripeThe structure of the sessions are sequential, stimulating and present opportunities for interleaved learning that benefits all childrenI would love to attend more and more sessions and roll it out across my year 1 teamI feel the staff, children and any volunteers are benefiting greatly by the active learning of core songs, language development and musical opportunitiesHeadteacher 4

6.5. Perceived Impact on Children’s Outcomes

6.5.1. Improvement in Children’s Confidence

The confidence of the children has improved greatly when singing and has also encouraged others with behavioural and social interaction difficulties to participate and end the project confident and happy to sing in front of others without concern. Children had opportunities to focus on their listening skills, develop their social interactions with others and also communicate their ideas in a concise way supported by their own experience evidence.Journal Teacher 7

From the observations and from feedback and discussions with the intervention staff, we all felt that the children had become more used to taking turns and choosing different partners to those that they would usually choose. I noticed that the children were encouraged to make eye contact which was especially helpful for those children who find this difficult. One child who is normally very shy and extremely quiet, beamed throughout the session as it gave her the opportunity to find her voice. In both classes I saw the children really listening to the instructions which were required for each activity.Headteacher 2

6.5.2. Perceived Impact on Children’s Language Development

Working in a multilingual school with children from many nationalities and various levels of English, the First Thing music programme has been a brilliant way to get all the children involved. So far I have had two entirely non- English speaking children join my class and one of them had never even been to a school setting before. At first he used to cry and scream at having to come to school, wouldn’t sit down on the carpet and definitely wouldn’t join in with social times such as playtime or lunch with the other children but gradually he would come and sit at the back of the hall during our music and then (with a little encouragement from my TA) he joined the circle. After a short while he was willing to join in with our welcome song and then he was the postman with ‘Early in the Morning’, which he did on his own! He now comes into the hall along with the others and participates with the others despite having no English. As for classroom behaviour, he is still struggling to sit and listen to stories and he’ll wriggle etc but if I sing his name or sing an instruction he will turn and correct himself! This is an absolute difference to when he first arrived.Journal Teacher 9

The music subject lead and I went in to see the First Thing Music session on Friday and were really impressed with how it is going–confidence, concentration, social skills, speaking and listening skills, musicality, enjoyment were all evident.Headteacher 1

With one child in particular who has speech and language issues, I have seen a great improvement. Before the First Thing Music project, the child was very hesitant to speak but he now joins in class discussions, shares answers and news and has clearer speech. This has been a wonderful development and huge achievement for this child.Journal Teacher 11

The children have a great understanding of music and can keep the steady beat, rhythm, change pitch and volume. They are even able to read music which is amazing. The children in my class performed better in the Year 1 Phonics Screening test than the control group. My class had a 91% pass rate whereas the control group had a 82% pass rate. Both classes have received the same teaching of phonics, the same scheme followed (Letters and Sounds) and the same resources used.Journal Teacher 11

6.5.3. Perceived Impact on Children’s Disposition for Learning

Children were happy and excited to come into school and start the day with singing. Developing this positive mind-set can only be constructive in supporting all learning and well-being.Journal Teacher 13

Kodály inspired music has given the children confidence to perform amongst their peers and unites them in the fun of music. No matter how they enter school, in the morning, once the singing starts their attitude changes and any negative emotions disappear.Journal Teacher 12

Having attended a couple of sessions it felt wonderful to be a part of the programme with a class of our Y1 children. I really enjoyed the games and the children sang really well. I think this kind of activity is having an impact as the children appear to be listening more attentively. Many children are able to keep a “steady beat” which I know will impact on many areas of the curriculum.Headteacher 5

The children are participating more with all aspects of the music and learning. Confidence is developing and I am particularly impressed with levels of focus and concentration which is transferring to other sessions.Headteacher 7

I have attended a number of music sessions over the term with squirrel class. I have noticed a real improvement in terms of their understanding of beat and also engagement of some of the harder to reach children.Headteacher 8

OFSTED Inspector X visited—was impressed that 5 yr old children were reading musical notation, as was a parent who was assessing local private education options, and changed their mind on the spot!Journal Teacher 6

R never really settled into school well and would often cling to me when dropping off. It is only since R started the First Thing Music that she’s been looking forward to arriving to school and doing some singing.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B. Teacher Training Package–Further Details/Examples

| Content | Notes |

|---|---|

| Introduction Theme of day—The Lego Approach or How to make the most of some basic materials/recycle/build a new game…. | The most basic components of music begin with

What can we make using this particular part of the lego set? |

| Surgery session—A large circle of 30-ish people, led by Zoe/Lindsay, discussing experiences, both positive and negative that have arisen over early weeks of the project. Examine any issues, and then split into groups with relevant music practitioners or specialists on subject. | Everyone has now had at least one week of daily music sessions in their classrooms and some experience of leading their own sessions (at least for a couple of days).

|

| New song—See the Candle Light (?) | Learn new song—(currently an extra, just for seasonal use, but later to teach concept of the ‘rest’ over the beat); incorporate in workshop below. |

| Exploring the ‘Lego’ aspect of a Kodály-inspired approach in more depth… Three stages interweaving throughout the ‘fabric’ of the activities:

| You do not necessarily need loads of new toys in the box—you can be endlessly creative with very little. Pedagogically, this means that learning can be about concepts and creativity rather than ticking off lists of material used. Musical behaviour is playful and being playful increases the chance that everyone will be enjoying themselves. When children are feeling happy and secure, this is likely to support the learning process.

|

| Workshop Group work, with each group undertaking to find new, creative ways of playing with two songs from the currently available repertoire. Share afterwards, with demonstrations. Pick out aspects of the games which correlate with the six points above. | There is always more than one way to play games with this material. It is almost like playing with Lego—the bricks will take deconstructing and reconstructing many times. The main thing for the teacher is to understand the underlying concept that we’re practising, and to keep 10 min of playing ‘on track’ with this in mind. |

Appendix C. Extract from the Introductory Pack and the 30-Item Repertoire List

See Also 87910 RESOURCE FILE_Layout 1

References

- Schellenberg, G. Music lessons enhance IQ. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henley, D. Music Education in England: A Review for the Department of Education and the Department for Culture, Music and Sport; Department for Education: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Linnavalli, T.; Putkinen, V.; Lipsanen, J.O.; Huotilainen, M.; Tervaniemi, M. Music playschool enhances children’s linguistic skills. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, S. The Power of Music: A Research Synthesis of the Impact of Actively Making Music on the Intellectual, Social and Personal Development of Children and Young People; Music Education Council: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, M. Effects of Sequenced Kodaly Literacy-Based Music Instruction on the Spatial Reasoning Skills of Kindergarten Students. Res. Issues Music Educ. 2003, 1, 4. Available online: http://ir.stthomas.edu/rime/vol1/iss1/4 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Daubney, A.; Spruce, G.; Annetts, D. Music Education: State of the nation. Report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group of Music Education, the Incorporated Society of Musicians and the University of Sussex. (Page 19). 2019. Available online: https://www.ism.org/images/images/State-of-the-Nation-Music-Education-WEB.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- EEF March 21 EEF Publishes New Analysis on Impact of COVID-19 on Attainment Gap|News|Education Endowment Foundation|EEF. Best Evidence on Impact of COVID-19 on Pupil Attainment|Education Endowment Foundation|EEF. Available online: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/eef-support-for-schools/covid-19-resources/best-evidence-on-impact-of-school-closures-on-the-attainment-gap/ (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- DfE. Teaching: High Status, High Standards (Circular 4/98); HMSO: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hallam, S.; Burnard, P.; Robertson, A.; Saleh, C.; Davies, V.; Rogers, L.; Kokotsaki, D. ‘Trainee primary school teachers’ perceptions of their effctiveness in teaching music. Music Educ. Res. 2009, 11, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mills, J. The Generalist Primary Teacher of Music: A Problem of Confidence. Br. J. Music Educ. 1989, 6, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Model Music Curriculum. 26th March 2021 Teaching Music in Schools—GOV.UK. Available online: www.gov.uk (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Pascal, C.; Bertram, T. How to Catch a Moonbeam and Pin It Down: Creativity and the Arts in Early Years; Amber Publications and Training: Birmingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Digby, J. Teacher Confidence to Facilitate Children’s Musical Learning and Development in the Reception Year at School. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, G.F. The challenge of ensuring effective early years music education by non-specialists. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse, D.; Brown, C.; Oliver, S.; Poblete, X. The BERA Close-to-Practice Research Project: Research Report; British Educational Research Association: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Barrett, M.S.; Zhukov, K.; Welch, G.F. Strengthening music provision in early childhood education: A collaborative self-development approach to music mentoring for generalist teachers. Music Educ. Res. 2019, 21, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, A.; Toh, G.-Z.; Wong, J. Primary school music teachers’ professional development motivations, needs, and preferences: Does specialization make a difference? Music Sci. 2018, 22, 196–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, H.; Button, S. The teaching of music in the primary school by the non-music specialist. Br. J. Music Educ. 2006, 23, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Julia, J.; Hakim, A.; Fadlilah, A. Shifting Primary School Teachers Understanding of Songs Teaching Methods: An Action Research Study in Indonesia. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2019, 7, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell-Bowie, D. What me? Teach music to my primary class? Challenges to teaching music in primary schools in five countries. Music Educ. Res. 2009, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, S. Approaches to increasing the competence and confidence of student teachers to teach music in primary schools. Education 2017, 45, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulter, V.; Cook, T. Teaching music in the early years in schools in challenging circumstances: Developing student teacher competence and confidence through cycles of enactment. Educ. Action Res. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenaler, D. Training Teachers with Little or No Music Background: Too Little, Too Late? Update Appl. Res. Music Educ. 2006, 24, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, B.H.; Morris, R.; Gorard, S.; Kokotsaki, D.; Abdi, S. Teacher Recruitment and Retention: A Critical Review of International Evidence of Most Promising Interventions. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.; Sims, S. Improving Science Teacher Retention: Do National STEM Learning Network Professional Development Courses Keep Science Teachers in the Classroom; Wellcome Trust: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis, K.J.; Wall, A.F.; Che, J. The Impact of Preservice Preparation and Early Career Support on Novice Teachers’ Career Intentions and Decisions. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 64, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glazerman, S.; Seifullah, A. An Evaluation of the Chicago Teacher Advancement Program (Chicago TAP) after Four Years; Final Report; Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, M.J.; City University of New York. Institute for Research and Development in Occupational Education; American Association of State Colleges and Universities. In Retired Teachers as Consultants to New Teachers A New Inservice Teacher Training Model; Final Report. Case 09–87ERIC Clearinghouse: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED306928 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Ronfeldt, M.; McQueen, K. Does New Teacher Induction Really Improve Retention? J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 68, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluschankof, C. Research and practice in early childhood music education: Do they run parallel and have no chance to meet? The case of preschool singing repertoire. In Proceedings of European Network for Music Educators and Researchers of Young Children; Young, S., Nicolau, N., Eds.; University of Cyprus: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2007; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S. Early Childhood Music Education Research: Research Studies in Music Education. Available online: rsm.sagepub.com (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Bremmer, M.; Hermans, C. What the body knows about teaching music. In Embodiment in Arts Education. Teaching and Learning with the Body in the Arts; Lectoraat Kunst-en Cultuureducatie: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, B. The Eclectic Curriculum in American Music Education: Contributions of Dalcroze, Kodaly, and Orff. Washington: Music Educators National Conference. 1972. Dewey Decimal Class-780/.72973; Library of Congress-MT3.U5 L33: ID Numbers-Open Library-OL5341967M; LC Control Number-72195923. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-eclectic-curriculum-in-American-music-of-and-Landis-Carder/c7e3fa53862c677c295d30c762c5f5b6bcd9cd78 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Caldwell, H.L.; Choksy, L. The Kodály Context: Creating an Environment for Musical Learning. Music Educ. J. 1981, 68, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlahan, M.; Tacka, P. Kodály Today: A Cognitive Approach to Elementary Music Education Inspired by the Kodály Concept; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bassanezi, R.C. Modelling as a teaching-learning strategy. Learn. Math. 1994, 14, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cruess, S.R.; Cruess, R.L.; Steinert, Y. Role modelling—making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ 2008, 336, 718–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Muijs, D.; Reynolds, D. Effective Teaching: Evidence and Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, Z. Music and Singing in the Early Years; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forrai, K. Music in Preschool, Translated and Adapted by Jean Sinor; Corvina: Budapest, Hungary, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- See, B.H.; Ibbotson, L. A feasibility study of the impact of the Kodály-inspired music programme on the developmental outcomes of four to five year olds in England. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 89, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- See, B.H.; Kokotsaki, D. Impact of arts education on children’s learning and wider outcomes. Rev. Educ. 2016, 4, 234–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, S. Integrating Inquiry-Based Constructivist Music Education with Kodaly-Inspired Learning. Aust. Kodaly J. 2019. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.104672790564030 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Bryant, L.; Gibbs, L. A Director’s Manual: Managing an Early Education and Care Service in NSW; Community Child Care Co-Operative, Ltd.: Marrickville, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, K.H. The Effects of Singing and Chanting on the Reading Achievement and Attitudes of First Graders. Ph.D. Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, L.M. The Integration of Music with Reading Concepts to Improve Academic Scores of Elementary Students. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B. A Formative Study of Rhythm and Pattern: Semiotic Potential of Multimodal Experiences for Early Years Readers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Register, D.; Darrow, A.-A.; Swedberg, O.; Standley, J. The Use of Music to Enhance Reading Skills of Second Grade Students and Students with Reading Disabilities. J. Music Ther. 2007, 44, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.P. The Effect of Music on the Reading Achievement of Grade 1 Students. Ph.D. Thesis, Jones International University, Centennial, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- An, S. The Effects of Music-Mathematics Integrated Curriculum and Instruction on Elementary Students’ Mathematics Achievement and Dispositions. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Courey, S.J.; Balogh, E.; Siker, J.; Paik, J. Academic music: Music instruction to engage third-grade students in learning basic fraction concepts. Educ. Stud. Math. 2012, 81, 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D.J. The Relationship between Creativity and the Kindermusik Experience. Master’s Thesis, University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg, MO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gromko, J.E.; Poorman, A.S. The Effect of Music Training on Preschoolers’ Spatial-Temporal Task Performance. J. Res. Music Educ. 1998, 46, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, H.; Mirbaha, H.; Pournaseh, M.; Sagan, O. Can music lessons increase the performance of preschool children in IQ tests? Cogn. Process. 2013, 15, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nering, M.E. The Effect of Piano and Music Instruction on Intelligence of Monozygotic Twins. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.J. Shake, rattle and roll—Can music be used by parents and practitioners to support communication, language and literacy within a pre-school setting? Educ. Int. J. Prim. Elem. Early Years Educ. 2011, 39, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, C.; Chobert, J.; Besson, M.; Schön, D. Music Training for the Development of Speech Segmentation. Cereb. Cortex 2012, 23, 2038–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moreno, S.; Marques, C.; Santos, A.; Santos, M.; Castro, S.L.; Besson, M. Musical Training Influences Linguistic Abilities in 8-Year-Old Children: More Evidence for Brain Plasticity. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Degé, F.; Wehrum, S.; Stark, R.; Schwarzer, G. Music lessons and academic self-concept in 12- to 14-year-old children. Music Sci. 2014, 18, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.A. Music Training Causes Changes in the Brain. Teach. Music 2010, 17, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Schlaug, G.; Norton, A.; Overy, K.; Winner, E. Effects of Music Training on the Child’s Brain and Cognitive Development. In The Neurosciences and Music II: From Perception to Performance; Avanzini, G., Lopez, L., Koelsch, S., Manjno, M., Eds.; New York Academy of Sciences: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M. The Effects of Music Instruction on Learning in the Montessori Classroom. Montessori Life 2008, 20, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Piro, J.M.; Ortiz, C. The effect of piano lessons on the vocabulary and verbal sequencing skills of primary grade students. Psychol. Music 2009, 37, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa-Giomi, E. The effects of three years of piano instruction on children’s cognitive development. J. Res. Music Educ. 1999, 47, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, I.; Grube, D.; Bongard, S.; Kreutz, G. Does music training enhance working memory performance? Findings from a quasi-experimental longitudinal study. Psychol. Music 2014, 42, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, I.; Wolff, P.H.; Bortnick, B.D.; Kokas, K. Nonmusical effects of the Kodaly music curriculum in primary grade children. J. Learn. Disabil. 1975, 8, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teachers’ Musicality | Agree | Not Agree | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| I enjoy listening to music | |||

| Before | 100 | 0 | |

| After | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| I often sing to myself | |||

| Before | 78.1 | 21.9 | |

| After | 95.1 | 4.8 | 5.6 |

| I have a good sense of rhythm | |||

| Before | 70.7 | 29.3 | |

| After | 87.8 | 12.2 | 2.98 |

| I am confident to perform music in front of other people | |||

| Before | 19.6. | 80.4 | |

| After | 51.2 | 48.8 | 4.3 |

| Teachers’ Music Practice in the Classroom | Agree | Not Agree | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| My normal teaching practice does not incorporate singing with my class. | |||

| Before | 29.2 | 70.8 | |

| After | 9.8 | 90.2 | * −3.8 |

| I am happier using a pre-recorded music lesson than leading a music lesson myself. | |||

| Before | 68.3 | 31.7 | |

| After | 39.0 | 61.0 | −3.4 |

| Music can be a useful behavioural tool in the classroom | |||

| Before | 75.6 | 24.4 | |

| After | 85.4 | 14.6 | 1.1 |

| I have a strong understanding of how to teach music to my class. | |||

| Before | 14.6 | 85.4 | |

| After | 73.2 | 26.8 | 15.98 |

| Teachers’ Attitude to Teaching Music | Agree | Not Agree | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Musical activity does not make teaching more enjoyable | |||

| Before | 29.3 | 70.7 | |

| After | 14.6 | 85.4 | −2.4 |

| Delighted to be involved in research | |||

| Before | 73.2 | 26.8 | |

| After | 80.4 | 19.6 | 1.5 |

| Agree | Disagree | Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I do not see music as a core activity in the national curriculum | |||

| Before | 29.2 | 70.8 | |

| After | 12.2 | 87.8 | −1.07 |

| I think that music helps to improve children’s scores in KS1 tests. | |||

| Before | 31.7 | 68.3 | |

| After | 41.5 | 58.5 | 1.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibbotson, L.; See, B.H. Delivering Music Education Training for Non-Specialist Teachers through Effective Partnership: A Kodály-Inspired Intervention to Improve Young Children’s Development Outcomes. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080433

Ibbotson L, See BH. Delivering Music Education Training for Non-Specialist Teachers through Effective Partnership: A Kodály-Inspired Intervention to Improve Young Children’s Development Outcomes. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(8):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080433

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbbotson, Lindsay, and Beng Huat See. 2021. "Delivering Music Education Training for Non-Specialist Teachers through Effective Partnership: A Kodály-Inspired Intervention to Improve Young Children’s Development Outcomes" Education Sciences 11, no. 8: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080433

APA StyleIbbotson, L., & See, B. H. (2021). Delivering Music Education Training for Non-Specialist Teachers through Effective Partnership: A Kodály-Inspired Intervention to Improve Young Children’s Development Outcomes. Education Sciences, 11(8), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080433