Towards a Global Entrepreneurial Culture: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

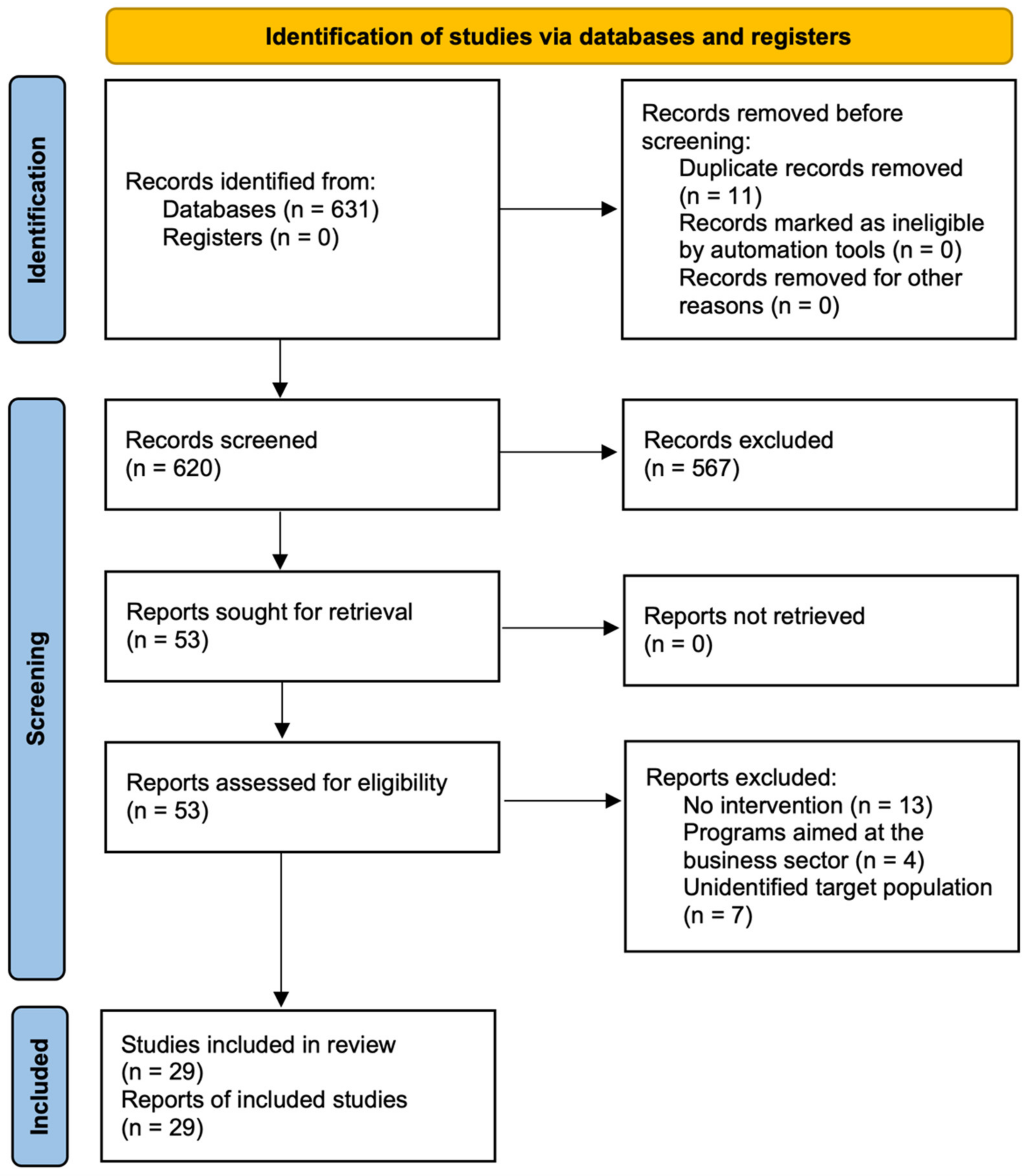

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Process of Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.3. Critical Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Studies

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

3.3. Results of Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pittaway, L.; Aissaoui, R.; Ferrier, M.; Mass, P. University spaces for entrepreneurship: A process model. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 26, 911–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J.; Franco, J.E. (Eds.) Empreendipédia—Dicionário de Educação para o Empreendedorismo; Gradiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T.; Chandran, V.G.R.; Klobas, J.E.; Liñán, F.; Kokkalis, P. Entrepreneurship education programmes: Howlearning, inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J. Regiões Empreendedoras: Descrição e avaliação dos contextos, determinantes e políticas favoráveis à sua evolução. Rev. Divulg Científica AICA 2020, 12, 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Porfírio, J.A.; Carrilho, T.; Felício, J.A.; Jardim, J. Leadership characteristics and digital transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, C.-G.; Sung, C.; Park, J.; Choi, D. A Study on the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs in Higher Education Institutions: A Case Study of Korean Graduate Programs. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carree, M.; Della Malva, A.; Santarelli, E.; Carree, M.; Malva, A.D.; Santarelli, E. The contribution of universities to growth: Empirical evidence for Italy. J. Technol. Transf. 2011, 39, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Sánchez-García, J.C.; Mayens, A.W. Impact of Entrepreneurial Education Programs on Total Entrepreneurial Activity: The Case of Spain. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheung, C.K. Entrepreneurship education in Hong Kong’s secondary curriculum: Possibilities and limitations. Educ. Train. 2008, 50, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkarim, A. Toward Establishing Entrepreneurship Education and Training Programmes in a Multinational Arab University. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2018, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R. Entrepreneurship Education in India: A Critical Assessment and a Proposed Framework. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2014, 4, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, J. Entrepreneurship in Western Europe: A contextual perspective. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1099–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, G. An examination of entrepreneurship education in the United States. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2007, 14, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, A.; Parton, B.; Robb, A. Entrepreneurship Education and Training Programs around the World: Dimensions for Success; World Bank Publications; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen, C.; Groenewald, D.; Davids, J.; Van Rensburg, L.J.; Schachtebeck, C. Best practice in entrepreneurship education. Probl. Perspect Manag. 2016, 14, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooper, A. Entrepreneurship: The Past, the Present, the Future. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Landström, H. The Evolution of Entrepreneurship as a Scholarly Field. Found. Trends® Entrep. 2020, 16, 65–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, J.A. The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrepreneurship education. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Entrepreneurship Education in Europe: Fostering Entrepreneurial Mindsets through Education and Learning; European Union: Oslo, Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N. Entrepreneurial Education in Practice: Part. 1—The Entrepreneurial Mindset; Secretary-General of the OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Comissão Europeia. Fomentar a Promoção das Atitudes e Competências Empresariais no Ensino Básico e Secundário; Comissão Europeia: Bruxelas, Bélgica, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Römer-Paakkanen, T.; Suonpää, M. Multiple Objectives and Means of Entrepreneurship Education at Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences; Haaga-Helia Publications: Helsinki, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Plourde, H.; Pelletier, D. Introduction to Entrepreneurial Culture; Gouvernement du Québec—Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport: Québec, Canada, 2007; 80p. [Google Scholar]

- Mwasalwiba, E.S. Entrepreneurship education: A review of its objectives, teaching methods, and impact indicators. Educ. Train. 2010, 52, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J. Programa de Desenvolvimento de Competências Pessoais e Sociais: Estudo para a Promoção do Sucesso Académico; Instituto Piaget: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dolabela, F. O Segredo de Luísa—Uma Ideia, Uma Paixão e um Plano de Negócios: Como Nasce o Empreendedor e se cria Uma Empresa; Editora de Cultura: São Paulo, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dolabela, F. Oficina do Empreendedor; Editora de Cultura: São Paulo, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- De Lourdes Cárcamo-Solís, M.; del Pilar Arroyo-López, M.; del Carmen Alvarez-Castañón, L.; García-López, E. Developing entrepreneurship in primary schools. The Mexican experience of “My first enterprise: Entrepreneurship by playing.”. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 64, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Sánchez, V.; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. The development of entrepreneurship at school: The Spanish experience. Educ. Train. 2016, 58, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J.; Soares, J.H.; Moutinho, A.; Calheiros, C.; Cardoso, P.; Cardoso, M.S. Brincadores de Sonhos; Theya: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, J.; Rodrigues, R.; Gouveia, T.; Pereira, M.; Gomes, F.; Paolineli, L.A.; Borges, L.; Lima, J.; Pinho, J.B. Exploradores de Sonhos; Theya: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hercz, M.; Pozsonyi, F.; Flick-Takács, N. Supporting a Sustainable Way of Life-Long Learning in the Frame of Challenge-Based Learning. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2021, 11, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkley, W.W. Cultivating entrepreneurial behaviour: Entrepreneurship education in secondary schools. Asia Pacific J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 11, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steenekamp, A.G.; Van der Merwe, S.P.; Athayde, R. An investigation into youth entrepreneurship in selected South African secondary schools: An exploratory study. South Afr. Bus. Rev. 2011, 15, 46–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, J.; Lima, J.; Grilo, C. Os Originais: Programa de Empreendedorismo Social com Jovens [The Originals: Program of Social Entrepreneruship with Youth]; Theya: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, H. Summer Entrepreneur an Activity for stimulating Entrepreneurship Among Youths: A Case Study in a Swedish County. US-China Educ. Rev. 2011, 1, 715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Obschonka, M.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. A new perspective on entrepreneurial regions: Linking cultural identity with latent and manifest entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcher-Mayr, M.; Mahlknecht, S. A Capability Approach to Entrepreneurship Education: The Sprouting Entrepreneurs Programme in Rural South African Schools. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2020, 11, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumberland, D.M. Training and Educational Development for “Vetrepreneurs”. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2017, 19, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwany, H.; Saad, F. Entrepreneurial education programmes and their impact on entrepreneurs’ attributes. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Dameri, R.P., Beltrametti, L., Eds.; ACPI: London, UK, 2015; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, R. Unpacking the link between entrepreneurialism and employability: An assessment of the relationship between entrepreneurial attitudes and likelihood of graduate employment in a professional field. Educ. Train. 2016, 58, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Kuratko, D.F. Building university 21st century entrepreneurship programs that empower and transform. Adv. Study Entrep. Innov. Econ. Growth 2014, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, A.; Price, A. A Compendium of Pedagogies for Teaching Entrepreneurship; IEEP and NCEE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupo, M.; Kampylis, P.; Punie, Y.; Van den Brande, G. EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Czyzewska, M.; Mroczek, T. Data Mining in Entrepreneurial Competencies Diagnosis. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebles, M.; Llanos-Contreras, O.; Yániz-Álvarez-De-Eulate, C. Perceived evolution of the entrepeneurial competence based on implementing a training program in entrepreneurship and innovation. Rev. Esp. Orientac y Psicopedag. 2019, 30, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, J. Entrepreneurial skills to be successful in the global and digital world: Proposal for a frame of reference for entrepreneurial education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J.; Pereira, A.; Vagos, P.; Direito, I.; Galinha, S.A. The Soft Skills Inventory: Construction procedures and psychometric analysis. Psychol. Rep. 2020, 0, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, J. 10 Competências Rumo à Felicidade: Guia Prático para Pessoas, Equipas e Organizações Empreendedoras; Instituto Piaget: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Gómez, F.I.; Miranda González, F.J.; Chamorro Mera, A.; Pérez-Mayo, J. Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Skills and Their Influence on the Entrepreneurial Intention of Academics. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402092741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RezaeiZadeh, M.; Hogan, M.; O’Reilly, J.; Cunningham, J.; Murphy, E. Core entrepreneurial competencies and their interdependencies: Insights from a study of Irish and Iranian entrepreneurs, university students and academics. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 35–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quieng, M.C.; Lim, P.P.; Lucas, M.R.D. 21st Century-based Soft Skills: Spotlight on Non-cognitive Skills in a Cognitive-laden Dentistry Program. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2015, 11, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Entrepreneruship Education: A Guide for Educators. EU Commission—Entrepreneurship 2020 Unit; Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Politańska, J. Best Practices in Teaching Entrepreneurship and Creating Entrepreneurial Ecosys; Fundacja Światowego Tygodnia Przedsiębiorczości: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ashoka, U.; Brock, D.D. Social Entrepreneurship Education Resource Handbook; Ashoka: Haryana, Índia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Checklist for Quasi-Experimental (Non-Randomized Experimental Studies); Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Checklist for Qualitative Research; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bártolo, A.; Santos, I.M.; Monteiro, S. Toward an Understanding of the Factors Associated with Reproductive Concerns in Younger Female Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar]

- Backs, S.; Schleef, M.; Buermann, H.W. Stand up–it’s all about the team? The composition of entrepreneurial teams in entrepreneurship education at a German university. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal Guerrero, A.; Cárdenas Gutiérrez, A.R. Evaluación del potencial emprendedor en escolares. Una investigación longitudinal. Educ. XX1 2017, 20, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bisanz, A.; Hueber, S.; Lindner, J.; Jambor, E. Social Entrepreneurship Education in Primary School: Empowering Each Child with the YouthStart Entrepreneurial Challenges Programme. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2020, 10, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boldureanu, G.; Ionescu, A.M.; Bercu, A.-M.M.; Bedrule-Grigorut, M.V.; Boldureanu, D.; Bedrule-Grigoruţă, M.V.; Boldureanu, D. Entrepreneurship Education through Successful Entrepreneurial Models in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dominguinhos, P.M.C.; Carvalho, L.M.C. Promoting business creation through real world experience: Projecto Começar. Educ. Train. 2009, 51, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. Évaluation d’une formation en entrepreneuriat: Prédispositions et impact sur l’intention d’entreprendre. Management 2009, 12, 175–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hebles, M.; Llanos-Contreras, O.; Yániz-Álvarez-de-Eulate, C. Evolución percibida de la competencia para emprender a partir de la implementación de un programa de formación de competencias en emprendimiento e innovación. REOP—Rev. Española Orientación y Psicopedag. 2019, 30, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, J.; Poikkijoki, S.A.; Vento-Vierikko, I. Entrepreneurship for Bioscience Researchers: A Case Study of an Entrepreneurship Programme. Ind. High. Educ. 2007, 21, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrick, S.A.; Cumberland, D.M.; Choi, N. Comparing military veterans and civlians responses to an Entrepreneurship education program. J. Entrep. Educ. 2016, 19, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.G.; Lee, J.H.; Roh, T.; Son, H. Social entrepreneurship education as an innovation hub for building an entrepreneurial ecosystem: The case of the KAIST social entrepreneurship MBA program. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9736. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Kim, D.; Lee, W.J.; Joung, S. The Effect of Youth Entrepreneurship Education Programs: Two Large-Scale Experimental Studies. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402095697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, R. Training entrepreneurship at a French grande école: The Projet Entreprendre at the ESC Rouen. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2005, 29, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubberød, E.; Pettersen, I.B. Exploring situated ambiguity in students’ entrepreneurial learning. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekoko, M.; Rankhumise, E.M.; Ras, P. The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education: What matters most? Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 12023–12032. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, E.; Zhang, L. Who does (not) benefit from entrepreneurship programs? Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Z.; Rezai, G.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Mahmud, M.M.A. Enhancing young graduates’ intention towards entrepreneurship development in Malaysia. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, M.; Langella, V.; Molteni, M. Do entrepreneurial education programs impact the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention? An analysis of an entrepreneurship MBA in Ghana. J. Enterp. Communities 2017, 11, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, M. Learning to be enterprising in school through an inquiry-based pedagogy. Ind. High. Educ. 2018, 32, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise Education: Influencing Students’ Perceptions of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M.I.; Fernandes, D.; Serrão, C.; Mascarenhas, D. Youth Start Social Entrepreneurship Program for Kids: Portuguese UKIDS-Case Study. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2019, 10, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rigg, E.; van der Wal-Maris, S. Student Teachers’ Learning About Social Entrepreneurship Education—A Dutch Pilot Study in Primary Teacher Education. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2020, 11, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Tan, S.; Ng, C.K.F. A problem-based learning approach to entrepreneurship education. Educ. Train. 2006, 48, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez–García, J.C.; Hernández–Sánchez, B. Influencia del Programa Emprendedor Universitario (PREU) para la mejora de la actitud emprendedora. PAMPA 2016, 13, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santini, S.; Baschiera, B.; Socci, M. Older adult entrepreneurs as mentors of young people neither in employment nor education and training (NEETs). Evidences from multi-country intergenerational learning program. Educ. Gerontol. 2020, 46, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J.; Collins, L.A.; Hannon, P.D. Embedding new entrepreneurship programmes in UK higher education institutions: Challenges and considerations. Educ. Train. 2006, 48, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundarajan, N.; Camp, S.M.; Lee, D.; Ramnath, R.; Weide, B.W. NEWPATH: An innovative program to nurture IT entrepreneurs. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2016, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ulvenblad, P.; Barth, H.; Ulvenblad, P.-O.; Ståhl, J.; Björklund, J.C. Overcoming barriers in agri-business development: Two education programs for entrepreneurs in the Swedish agricultural sector. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2020, 26, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Yuan, C.-H.; Pan, C.-I. Entrepreneurship Education: An Experimental Study with Information and Communication Technology. Sustainability 2018, 10, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, W.H.; Kao, H.Y.; Wu, S.H.; Wei, C.W. Development and evaluation of affective domain using student’s feedback in entrepreneurial Massive Open Online Courses. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.E.; Thornhill, S.; Hampson, E. Entrepreneurs and evolutionary biology: The relationship between testosterone and new venture creation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2006, 100, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athayde, R. Measuring enterprise potential in young people. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.S.; Gregoire, D.A.; Stevens, C.E.; Patel, P.C. Measuring entrepreneurial passion: Conceptual foundations and scale validation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 373–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, J.C. Evaluación de la personalidad emprendedora: Validez factorial del cuestionario de orientación emprendedora (COE). Rev. Latinoam Psicol. 2010, 42, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; General Learning Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman and Company: New York, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dillenbourg, P.; Traum, D. Sharing solutions: Persistence and grounding in multimodal collaborative problem solving. J. Learn. Sci. 2006, 15, 121–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolabela, F. Teoria Empreendedora dos Sonhos. In Empreendipédia—Dicionário de Educação para o Empreendedorismo; Jardim, J., Franco, J.E., Eds.; Gradiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019; pp. 713–718. [Google Scholar]

- Jardim, J.; Soares, J.H.; Moutinho, A.; Calheiros, C.; Cardoso, P.; Cardoso, M.S. Brincadores de Sonhos—Roteiro para Docentes e Formadores; Theya: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lackéus, M.; Sävetun, C. Assessing the Impact of Enterprise Education in Three Leading Swedish Compulsory Schools. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57 (Suppl. 1), 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.E. Capital Social. In Empreendipédia—Dicionário de Educação para o Empreendedorismo; Jardim, J., Franco, J.E., Eds.; Gradiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019; pp. 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.E. Cristianismo e solidariedade: A utopia da misericórdia. Brotéria 2014, 179, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.E.; Jardim, J. Para um projecto de educação integral Segundo Manuel Antunes, SJ e um novo programa de competências. Linhas Florianópolis 2008, 9, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.E. Europa ao Espelho de Portugal: Ideia(s) de Europa na Cultura Portuguesa; Temas e Debates: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fiolhais, C.; Franco, J.E.; Paiva, J.P. (Eds.) História Global de Portugal; Temas e Debates: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, M.P. “La fábrica de sueños”: Programa de Educación Emprendedora para alumnos de la escuela primaria y media. Ing. Solidar. 2015, 11, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollough, M.A.; Devezer, B.; Tanner, G. An alternative format for the elevator pitch. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2016, 17, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J.; Silva, H. Estragégias de educação para o empreendedorismo. In Empreendipédia—Dicionário de Educação para o Empreendedorismo; Jardim, J., Franco, J.E., Eds.; Gradiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019; pp. 338–342. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year | Country | Sample | Research Design | Program Name | Recipients | Outcomes | Male | Female | Ages | Total Training Hours | Program Facilitator | Conceptual Framework | Assessment Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backs et al., 2019 [62] | Germany | 43 | Qualitative design | Practice in Entrepreneurship | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial skills | 25 | 18 | 18–25 | 6 months—36 h | Teachers and entrepreneurs | Collaborative learning | Interviews |

| Bernal Guerrero et al., 2017 [63] | Spain | 52 | Mixed method study design | Emprender en mi Escuela + Empresa Joven Europea + ÍCARO | Primary and middle education | Entrepreneurial skills | 26 | 26 | 10–12, 14–16 | 9 months—36 h | Teachers | Social learning theory | Questionnaire |

| Bisanz et al., 2020 [64] | Austria | 139 | Qualitative design | Empowering Each Child | Primary education | Self-confidence, spirit of initiative, innovation, creativity, mindfulness, empathy, self-motivation, and participation in society | - | - | 25–60 | During the field trial, a two-year in-service training, consisting of 3 training courses per year | Teachers | - | Interviews and questionnaires. |

| Boldureanu et al., 2020 [65] | Romania | 30 | Mixed method study design | Business Creation | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial skills | 9 | 21 | 22–46 | 6 months—36 h | Teachers | Learning by doing | Focus group |

| Dominguinhos & Carvalho, 2009 [66] | Portugal | 22 | Case study | Projeto Começar | Professionals | Business and entrepreneurial skills | 11 | 11 | 25–29 | 924 h (6 months) | Academic tutor in higher education institution and business tutor | “Adaptive” learning | Questionnaire |

| Fayolle & Gailly, 2009 [67] | France | 158 | Quasi-experimental design | Programme d’Enseignement en Entrepreneuriat | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial behavior | - | - | 23 more | 24 h | Teachers | Solution-based coaching | Interviews and questionnaire |

| Hebles et al., 2019 [68] | Chile | 38 | Qualitative design | Programa de Educación en Emprendimiento e Innovación | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial skills and behavior | 19 | 19 | 18–25 | 9 months—36 h | Teachers | Self-efficacy theory | Focus group |

| Heinonen et al., 2007 [69] | Finland | 34 | Case study | Entrepreneurship Programme | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial and business skills, knowledge, attitudes, and experience | - | - | 18–25 | 9 months—36 h | Teachers | Theory of planned behavior | Focus group |

| Kerrick et al., 2016 [70] | USA | 121 | Pre-post study | Launch It | Professionals | Networking, entrepreneurship concepts, definition of target markets, market research, concept prototyping, financial markets, and intellectual property | 87 | 34 | 50–70 | 10 weeks—30 h | trainer and experts in the community (lawyers, etc.) | Social entrepreneurship education model | Diaries; accountability documents; group interview |

| Kim et al., 2020 [71] | Korea | 1934 | Quasi-experimental design | KAIST Social Entrepreneurship MBA Program | Secondary education | Social entrepreneurial skills | - | - | 30–60 | 2 years | Teachers | Theory of entrepreneurial ecosystem | Survey |

| Kim et al., 2020 [72] | Korea | 106 | Case study | Entship School + Hero School | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial, business, and self-efficacy skills | 957 | 977 | 12–20 | Entship School—12 h Hero School—20 h | Teachers | Development of a business model | Semi-structured interviews and questionnaires |

| Klapper, 2005 [73] | France | 83 | Qualitative design | Project Entreprendre | Higher Education | Teamwork, business plan, interactivity, self-confidence, credibility, balance between formal, and informal. | - | - | 19–21 | 5 months | Teachers, consultors | Theory of planned behavior | Questionnaires |

| Kubberød et al., 2017 [74] | Norway | 24 | Qualitative design | The Norwegian School of Entrepreneurship | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial, business, and self-efficacy skills | - | - | 23 | 3 months—48 h | Teachers | Develop local economies | Assessment report and interviews |

| Lekoko et al., 2012 [75] | Botswana | 325 | Case study | Entrepreneurship Education | Higher Education | Awareness that entrepreneurship education in Botswana does not develop entrepreneurial skills, which makes it impossible to pursue a career in the field of entrepreneurship | - | - | 18–25 | - | Teachers | Social entrepreneurship education model Ukids | Questionnaires |

| Lyons et al., 2018 [76] | USA | 335 | Qualitative design | Next 36 | Secondary education | Increased likelihood of working or founding a startup | 0 | 335 | 18–25 | 1 year | Teachers, entrepreneurs, funders | Theory of planned behavior | Questionnaires |

| Mohamed et al., 2012 [77] | Malaysia | 410 | Qualitative design | Basic Student Entrepreneurship Program | Higher Education | Skills to take advantage of business opportunities, marketing, entrepreneurial simulations, and analysis of the characteristics of successful entrepreneurs | - | - | 18–40 | 6 months—36 h | Teachers | Skills development | Interviews and questionnaires |

| Pedrini et al., 2017 [78] | Ghana | 30 | Mixed method study design | E4impact MBA | Higher Education | Business plan, international network of partners and investors | 25 | 5 | 27–49 | 12 months—24 h | Teachers | Active aging approach | Questionnaires |

| Pepin, 2018 [79] | Canada | 19 | Case study | School Shop Project | Primary education | Experience of what it means to be an entrepreneur | 9 | 10 | 7–8 | entire school year (from September to June) | Teachers | Skills development | Interviews |

| Peterman et al., 2003 [80] | Australia | 236 | Pre-post study | Young Achievement Australia | Secondary education | Perception of the benefits of starting a business; of the benefits of EE programs for training potential entrepreneurs as a professional career option | 90 | 146 | 15–18 | 9 months—36 h | Teachers and volunteers | Theory of planned behavior and Role theory. | Questionnaires |

| Pinho et al., 2019 [81] | Portugal | 24 | Case study | UKids | Primary education | Valuation of individual capacities, such as creativity, self-confidence, the power of argument, as well as the construction of social skills, in interpersonal and group relationships; motivation to work on public causes in the logic of sustainable development, and openness to new concepts, such as creativity, respect for the environment, cooperation, communication of ideas. | 24 | 24 | 8–10 | entire school year | Teachers | Theory of planned behavior | Questionnaires |

| Rigg et al., 2020 [82] | Netherlands | 8 | Pilot study | UKids | Professionals | Social entrepreneurial skills | - | - | 18–25 | 7 months | Teachers | Practice-based wisdom theory and Entrepreneurial ecosystem | Interviews |

| San Tan et al., 2006 [83] | Singapore | Pilot study | Problem-Based Learning | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial skills | - | - | 18–25 | 16 weeks in a semester—32 h | Facilitator | - | Interviews and questionnaires | |

| Sánchez–García & Hernández–Sánchez, 2016 [84] | Spain | 310 | Quasi-experimental design | PREU | Higher Education | Self-efficacy, proactivity and risk, finance, marketing, management; skills such as self-efficacy, proactivity, and risk; interactive practice with entrepreneurs | 177 | 133 | 19–22 | 8 months—28 h | Teachers | Problem-based learning | Focus group |

| Santini et al., 2020 [85] | Italy, Germany and Slovenia | 41 | Pre-post study | Be the Change | Professionals | Mentoring skills, for example, active listening and guidance, improving well-being and self-esteem, an attitude of social inclusion and active aging. Business and socio-relational skills, for example, benefiting from the full exploration of the mentors’ know-how and their relationship and trust. | 41 | 33 | 18–29 / 55–70 | OAEs—16 h of training Mentees—20 sessions (40 h) | Mentors, technical experts in education | Constructivist model | Focus-group and Peer-evaluation |

| Smith et al., 2006 [86] | United Kingdom | 16 | Qualitative design | Discovering Entrepreneurship | Higher Education | Extroversion, taking risks, tolerance of ambiguity and novelty, independence, leadership, finding opportunities, creativity, and problem solving, contacts and social networks, interpersonal skills. | 8 | 8 | 18–25 | 10 sessions—20 h | Teachers | Learning by doing | Focus group and follow-up interviews. |

| Soundarajan et al., 2016 [87] | USA | 98 | Quasi-experimental design | Newpath | Higher Education | Entrepreneurial skills | - | - | 18–25 | 3 weeks (campus and visit to Silicon Valley) + 12 weeks (internship in a company)—375 h = 15 weeks 5 h | Teachers + internship supervisors + local businessmen | Shapero’s Model | Questionnaires |

| Ulvenblad et al., 2020 [88] | Sweden | 109 | Mixed method study design | Leader Practice + Lean Agriculture | Professionals | Self-leadership and team leadership, delegation of tasks, communication with employees and family, work routines, time management. | - | - | 50 + 53 years—average | Trainers and Coaches | - | Questionnaires | |

| Wu et al., 2018 [89] | Taiwan | 21 | Mixed method study design | PowToon | Higher Education | Perception that animated presentations attracted more investment; creating videos helped the team better present their business ideas to investors; whoever generates a business idea does not necessarily influence investor decisions. | 25 | 20 | 23 | EMBA—36 h | Teachers | Theory of planned behavior | Questionnaires and interviews |

| Wu et al., 2019 [90] | Taiwan | 32 | Qualitative design | MOOCs course | Higher Education | Social entrepreneurship courses with a mixed approach can be used effectively to help students achieve different levels of teaching objectives in the affective domain, which is a lengthy process, especially at higher education levels. | 12 | 20 | 21–24 | 9-week course—18 h | Teachers | Approach constructivist-interpretive | Interviews and focus groups |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jardim, J.; Bártolo, A.; Pinho, A. Towards a Global Entrepreneurial Culture: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080398

Jardim J, Bártolo A, Pinho A. Towards a Global Entrepreneurial Culture: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(8):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080398

Chicago/Turabian StyleJardim, Jacinto, Ana Bártolo, and Andreia Pinho. 2021. "Towards a Global Entrepreneurial Culture: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs" Education Sciences 11, no. 8: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080398

APA StyleJardim, J., Bártolo, A., & Pinho, A. (2021). Towards a Global Entrepreneurial Culture: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education Programs. Education Sciences, 11(8), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080398