Abstract

This paper presents an evocative autoethnographic account of my postgraduate supervision experience in two African institutions while dealing mainly with students in the computing disciplines of Computer Science, Information Systems, and Information Technology. In this paper, the context of the postgraduate supervision, and the lessons learnt are presented based on personal reflection, students’ feedback, and retrospective analysis on my activities as an absorbed participant in the supervision process. The reflection of my supervision process offers vital lessons for all supervisors in the developing country context who are torn between the requirements for the student to do quality work and get published in top journals, and the challenges in their operational environment and students’ lives. The study also recommends some good practices that could help supervisors that are operating in similar contexts to mine.

1. Introduction

In many African institutions, sound academic scholarship is assessed based on the quality of academic publications, volume and quality of publications, the regularity of publishing, the record of postgraduate supervisions, grant awards, and service to the academic community in general [1,2]. For those in the professorial cadre, postgraduate supervision plays a big part in attaining these achievements. Students are key actors that help in the delivery of these academic achievements by a professor. The typical automation procedure of IPO—Input—Process—Output is a good analogy. The supervisor gives input by sharing his ideas, insight, learning, and experience with the student, who processes all these as fueled by his/her motivation, and intellectual ideas to generate outputs in the form of a completed thesis, journal/conference papers, and at times patentable products and innovations. In many cases, the quality of the input from the supervisor and the quality of the processing by the student determines the quality of the outputs.

The greatest academics that I have met are not just brilliant and resourceful, they are also adept at managing the human and material resources at their disposal to achieve great results. These human resources are mostly in form of postgraduate students (masters, doctoral), postdoctoral fellows, and research collaborators. Most of the time, supervisors provide direct guidance to postgraduate students and postdoctoral fellows. When the supervisor is a good manager of human resources and there is a pool of human talents available, the results are usually great and exceptional, but when this is not the case, the result may just be adequate or below expectation. The best scenario is when a sound and motivated supervisor has a talented pool of motivated students to work with [3,4].

From my experience, the pressure to perform or deliver good results can make a supervisor want to push students too hard without paying adequate attention to other non-academic needs that they have, which does not always augur well [5,6]. When dealing with students that can cope well with pressure, the effect of this may not be so obvious, but for students that have a different psychological composition, it does not yield a good outcome [6]. The task of finding the right balance of interaction between the need for academic rigor in a student’s work and humanity in the student–supervisor relationship is a major responsibility of a supervisor. According to [7], students prefer supportive supervision instead of aggressive supervision.

So far, my supervision has been guided by a personal pedagogical philosophy that dictates that a teacher (or supervisor) must support students to acquire the requisite epistemological foundations that will enable them to thrive in a world of lifelong learning. I seek to inspire and enable students to become independent learners who will continuously evolve their knowledge through self-learning to attain the mastery of the knowledge and skills that are required for them to excel in their chosen field of practice. In this paper, I will reflect on my experience of postgraduate supervision of students of computing in two universities in two different countries in Africa over 12 years. The investigation is guided by three research questions which are: (i) What are the main observations from my supervision experiences in the past 12 years? (ii) What are the good practices in my supervision in the past 12 years? (iii) What are the things to avoid based on my experiences in the past 12 years?

My objective is to answer these questions through a critical reflection on my supervision process to identify vital lessons that could lead to an improvement of my practices and to articulate my findings in a way that could enable other supervisors to learn from them. I believe other supervisors can learn vital lessons from my experiences which could be applied to improve their supervision practices. Autoethnography was adopted as the methodology for the inquiry which enables me to share my picture of postgraduate supervision in the African context in terms of the challenges, and constraints that exist, and a set of replicable good practices that helped me to navigate the culture and process of supervision in Africa. This is expected to offer useful lessons for other practitioners in similar cultures. Autoethnography or personal ethnography is a form of qualitative research inquiry that enables a researcher to report a personal lived experience to create a social understanding of a cultural experience [8,9,10]. This paper presents a reflection of my supervision practices to provide a social understanding of the nature of postgraduate supervision in the African context from the lens of my lived experience of supervision in two African universities in two countries. As a contribution, this paper extends the discussion on the issues of postgraduate supervision in Africa, and supervision best practices, which are valuable for both postgraduate students and supervisors.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents background on autoethnography as an academic practice and an overview of related work. Section 3 describes the context of the study, while the adopted methodology is presented in Section 4. Section 5 presents the findings and discussion, and the paper is concluded in Section 6 with a brief note.

2. Background and Related Work

In this section, I will present an overview of autoethnography as a qualitative practice, and a review of previous cases where autoethnography was used to report on the culture of supervision in the African context.

2.1. Autoethnography

Autoethnography is an approach to qualitative research that makes the researcher the object of analysis. It promotes self-reflection on the lived experiences and activities of the researcher in the past to foster an understanding of a cultural phenomenon. Autoethnography as a concept borrows from the principles of autobiography and ethnography. It allows the use of hindsight and retrospection to write about past experiences (autobiography) that relates to a particular culture (ethnography) [8].

Thus, research methods such as narrative inquiry, analysis of experiences, and storytelling, showing and telling, are commonly used by autoethnographers [9]. The sources of data collection include field notes, interviews, and archival materials, thus making characteristics of a culture familiar to both insiders and outsiders [9]. An autoethnographic account is writing that is emotionally engaging and demonstrates a critical self-reflection of the researcher on the topic. Compared to other forms of qualitative research, autoethnography is relatively new. It accommodates subjectivity of findings, emotionality in presentation, and the influence of the researcher on the research [8,9].

According to [11], due to its unique nature, the traditional mode of the assessment of qualitative research may not apply to autoethnography. Thus, based on the perspectives of [9,12,13], Lucero in [8] identified seven criteria for writing autoethnography. These are (i) establishing boundaries—entails delimitation of the study in terms of time, location, project type, and point of view; (ii) authenticity which is also referred to as reliability and construct validity [9,12]—entails defining a protocol that makes the procedure followed in the study to be replicable by someone else; (iii) plausibility—entails presenting the narrative in a way that follows a specific academic article style, and showing that it is motivated by gaps in the literature; (iv) criticality—entails guiding readers through imagining ways of thinking and acting differently; (v) self-revealing writing—entails giving unflattering and transparent details about the autoethnographer; (vi) linking of ethnographic materials and confessional content in a way that limits personal content to only what is relevant to the research topic; and (vii) generalizability—entails ensuring that the story speaks to readers and others they know. These seven criteria have been applied in writing this autoethnography.

2.2. Related Work

This section presents an overview of autoethnography in postgraduate supervision in Africa. In [14] an autoethnographic report of the importance of socio-technical enrollment of the student into key aspects of the doctoral studies that are critical for the successful education of a doctoral student was presented. The fieldwork for the research was done in the Benin Republic. In the study, the term enrollment was used to mean the initiation of a doctoral student to knowledge aspects. The author applied autoethnography as the research methodology by engaging in self-reflection on the different stages of his doctoral training with an emphasis on the interaction and collaboration with his thesis supervisor between March 2012 and October 2016. The findings show that enrollment of the doctoral student in key aspects of the doctoral journey is very critical for success. The enrollment responsibilities include enrollment in how to recognize leading authors and journals in the field, enrollment in proposal preparation, enrollment in fieldwork preparation, enrollment during fieldwork, enrollment in dissertation writing, and enrollment in choosing a postdoctoral career path. The author observed that a supervisor must provide a doctoral student with necessary initial guidance in these aspects to succeed.

In [15], the author explained how the experiences of a supervisee can have a profound influence on the identity and practices of a doctoral supervisor. Autoethnography was used to investigate the author’s supervision over six years in South Africa. By using the methods of reflection, critical and narrative analysis, and observation of the culture of doctoral supervision. The findings of the study revealed the need for universities to promote in-service training of supervisors in doctoral supervision, training in research philosophy, and educational research. Emerging supervisors were also encouraged to take advantage of capacity building opportunities and training on doctoral supervision. The author further recommended the need to intensify autoethnographic studies which will engender more dialogue on topics around the culture of doctoral supervision.

In [2], autoethnography was used to critically examine the role of a postgraduate supervisor. The context is a distance education institution in South Africa where supervision is done by using a combination of face-to-face contact and distance education. The paper was based on the author’s self-reflection and explicit theorizing based on generativity theory. The author observed that autoethnography is capable of fostering self-understanding and social understanding of the role of a postgraduate supervisor. In [16], the author gave a personal account of how graduate students of Open Distance Learning (ODL) were supervised by using personal mobile devices. The author applied autoethnography by presenting a reflective narrative of m-learning and m-supervision that occurred. The study found that the informal social environment enabled the blending of the affective domain, rationality, and autonomy in supervision. It also revealed the potential of using informal methods of supervision, and the need to design supervisory pedagogy for mobile devices.

Lastly, [17] presents an analytical autoethnography that discussed how analytic ethnography was used to resolve the dilemmas that the author faced during postgraduate supervision by applying the theory of transformative learning. The author observed that autoethnography have some limitations which include the fact that it may require more time to learn than is available for professional development, and a lack of skills to do autoethnography. However, the author advocated for the use of analytic autoethnography as a tool for the professional development of supervisors and academic staff in universities.

The autoethnographic account presented in this paper is different to the earlier studies where autoethnography was related to supervision in Africa. The difference between this paper and others stems from the context of the supervision which spans two universities in two African countries, and the fact that the autoethnographic account pertains to supervision done in the computing disciplines. Thus, this autoethnographic study offers valuable insights for supervisors in the computing field and other disciplines in Africa. It presents a critical reflection on postgraduate supervision, and supervision best practices in the context of African institutions, which provides vital lessons for other supervisors to enhance their supervision practices.

3. Context

The supervision practices discussed in this paper pertains to the author’s activities in two African universities. The first, University A designated as UA in this paper is a private university in Nigeria, while the second, University B, designated as UB is the University of Technology in South Africa. The context of the postgraduate supervision shall be discussed in terms of the (i) institutions (ii) supervisors; and (iii) students.

3.1. Institutional Contexts

The two African institutions UA and UB used as cases have many things in common although a few differences still exist.

UA is a small and research-intensive private university in Nigeria. Staff and students are encouraged to give a lot of their time to research, leading to academic publications in recognized indexes such as Scopus and the Web of Science. There is a strong emphasis on research productivity in UA.

UB is a University of Technology (UoT) in South Africa. Staff are encouraged to pursue excellence in teaching and learning and research. Greater research responsibilities are assigned to the senior academics (Senior Lecturers, and Professors) who are expected to supervise postgraduate students and attract grants to the university. The students are usually integrated into the research space through mentoring and leadership provided by their supervisors. Both staff and students are encouraged to publish in journals and conference outlets that are accredited by the South African Department of Education (DHET). These include Scopus, the Web of Science, and other DHET approved outlets.

In the two institutions, the requirements for admission into the master’s program is generally a good bachelor’s degree or equivalent with an aggregate score of 60% or above. Enrollment into a doctoral program also requires a relevant master’s with an aggregate score of 60% or above. In both cases selection for admission is competitive since a limited number of students are admitted based on the quota allocation for a specific programmed in a particular year. The requirements for graduation after completing a master/doctoral thesis includes evidence of publication in accredited academic journals or peer-reviewed conferences. A master’s student is expected to publish at least a peer-reviewed paper in an accredited conference or journal. For doctoral students, the minimum is an article in an accredited journal. UA demands at least 1 published journal article plus conference papers, while University B requires a minimum of 1 published journal article. In both institutions, a master’s thesis or a doctoral thesis that is submitted by a student is subjected to external examination by experts in the discipline from other academic institutions that are appointed nationally and internationally. Success in the external examination precedes a recommendation for the award of the postgraduate degree.

It is also worth mentioning that these two universities, UA and UB in terms of facilities for teaching and learning and supportive infrastructure for research by staff and students belong to the group of the relatively more resourced universities in Africa. There are many universities in Africa where supervision takes place but they are not as endowed in terms of resources as UA and UB.

3.2. Student Context

The students in UA were mostly nationals (Nigerians) with relatively few foreign students. All students are fluent in spoken English and had their education in English before coming for postgraduate study. The student composition in UB is more diverse, with students from various parts of Africa. Some of the students are from French and Portuguese speaking African countries whose primary language of learning in the early stages of their education was not the English language. Some learnt the English language while in South Africa before the commencement of their undergraduate education in South Africa, and at completion decided to continue their education to the postgraduate level.

In both institutions, postgraduate students are enrolled in either full-time or part-time academic programs. The full-time students are expected to finish within a shorter period compared to the part-time students. Also, many students, although enrolled as full-time are engaged in full-time work or some form of gig work to sustain themselves while studying since most are self-sponsored. There are few grant opportunities that students can apply for if they meet the requirements.

3.3. Supervisor’s Context

The work environment of supervisors in both institutions are quite similar. Supervisors usually combine postgraduate supervision with their teaching duties at the postgraduate level or undergraduate level. Some supervisors have a small teaching load which allows them to do more supervision than teaching while for others it is the opposite. Aside from teaching and supervision, academics in these two institutions are also expected to contribute to community engagement activities, foster industry partnership, and serve in university committees. Thus, the postgraduate supervision is done in addition to other key activities. In all cases, the supervisor needs to find the right balance to ensure that work time is shared among the different roles.

4. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a qualitative approach and uses autoethnography as the method of enquiry. Autoethnography enables the researcher to position as the source of an enquiry, and the primary source of data generation [8]. Data is collected through reflection, retrospection, and an analysis of my activities as a supervisor. The data was gathered from reflection on the process and the outcomes of my supervision activities in terms of successes and failures, commendations and critiques, and feedback obtained through interactions with students during supervision meetings, verbal conversations with students, student testimonials, evaluation reports and email exchanges with students from 2009 to 2021. All these were analyzed to provide answers to three research questions that I formulated which focused on key observations from my supervision, the good practices, and weaknesses and missteps that should be avoided.

According to [18], self-reflective research involves an “enquiry conducted by the self into the self”. This enables the researcher to assess his practice against his own subscribed pedagogical values [19]. The context of this study is the two universities where I have supervised postgraduate students. The study sought to identify the characteristics of my supervision experience, the key principles and practices that are considered good because they aided good outcomes, and the shortcomings that affected good outcomes. The good practices were presented as a framework that can be adopted by other supervisors in the computing disciplines.

5. Results

In the sequel sections, the findings from reflection on my supervision activities in Computer Science, Information Systems, and Information Technology over 12 years in UA and UB are captured concerning the three research questions. Each of these is succinctly described below.

5.1. What Are the Main Observations from My Supervision during the 12 Years? (R1)

5.1.1. All Students Are Motivated to Succeed, but for Different Reasons

My observation from interactions with students that I supervised is that they all want to succeed in their studies, by obtaining good results and finishing in good time without spending extra years. However, the basis of this motivation differs. I found that the type of motivation tends to influence a student’s conduct and performance when under supervision [3]. My usual practice is to request a student to share his/her motivation with me in our first meeting. I seek to know why the students aspire to earn a higher degree and has opted to work with me. I typically ask the question “Why do you seek a master’s degree?” or Why do you seek a PhD”. I also ask why do you want to work with me? The response to this second question is always very satisfactory because it is always very positive. Most times the students report that they felt that I am a good match for their area of research interest, while some claimed that they have heard positive things about me and felt they could work with me. The response to the first question on their motivation is not always as good as expected. For some, the motivation is that a higher degree will enhance their status in the workplace by getting promoted or being able to seek better employment elsewhere. Some aspire to study for a doctoral degree; hence they have enrolled for a master’s program. It is on few occasions, that I get responses that suggest that the student is motivated by a desire to gain advanced knowledge in the field. Most of those in this category are also aware that some benefits will also be derived through the advanced knowledge gained, which will confer benefits on them professionally and career-wise. Some could not find a job with their current qualification due to the problem of high unemployment and thinks a higher degree will enhance their chances of getting a job. Some students are lecturers, so they need a higher degree to get ahead which was why they enrolled for a higher qualification.

5.1.2. Students Have Different Learning Needs due to the Problem of Unequal Education

I found that students have different educational needs as a result of the quality of their prior learning. According to van Rooij [4], supervisors must be responsive to students learning needs. Computer Science and the other computing disciplines are relatively new in many African universities compared to older disciplines such as Mathematics, Natural Sciences (Physics, Chemistry, Biology), or Engineering. Thus, students come into the postgraduate program with unequal footing depending on the universities they graduated from. Some students come with strong technical skills in programming, the theoretical aspects like mathematics, algorithm design, and problem-solving while some are not strong in these areas. Some have good technical skills but struggle with writing and communication skills. I had students that said they only read AI and Expert Systems on their own but were never taught AI during their undergraduate studies. However, coming into the master/doctoral program, they developed an interest in AI and want to take up a research project in AI. This becomes challenging for the student and a supervisor because of the weak foundation. Also, most students lack an understanding of research methodology when they come into the postgraduate program, while many do not understand the tenets of academic writing. This reveals that undergraduate education does not adequately prepare many students for research-based study at the postgraduate level [20]. However, there are few instances where I had students that met many of my expectations and were more prepared for postgraduate studies because they graduated from universities that placed stronger emphasis on aspects that prepared them for research. Thus, the skills that students lack is traceable to the quality of their prior learning, not according to their academic potential and cognitive ability. The huge socio-economic gap in African society has amplified the problem of unequal education [21]. Different standards of education exist in Africa. Hence, in many cases, the African child is constrained right from the primary school level to the tertiary education level to access educational opportunities based on the socio-economic status of the parents. However, I found that when these knowledge deficiencies are spotted early and addressed by giving students in this disadvantaged category the right information and orientation, they were able to learn fast enough to cover the gaps and raise their performance level.

5.1.3. It Is Teaching-Cum-Supervision Not Just Supervision

The inherent deficiencies in undergraduate education in preparing many students for research-based postgraduate education demand that a supervisor creates a platform for teaching relevant aspects that will aid the students in their research [6,20]. Usually, academic departments, faculties, and universities have scheduled events and programs geared at developing the capacity of postgraduate students in research. These are usually in the form of short courses on research methodology, departmental postgraduate research seminars, research symposiums/colloquiums, and invited talks by experts, which students are expected to participate in. I found that these were never sufficient. Still, the supervisor must ensure that all the information that a student might have been received from these different sources are properly digested and related to the student’s specific study. Most times students suffer from information overload and even get confused after exposure to some of the seminars. I discovered the need to have regular teaching sessions on research methodology that are specifically tailored to the needs of students under my supervision so that they can make acceptable progress. These also include one-to-one mentoring sessions to help students properly contextualized all the information that they have gathered from diverse sources including their readings. Thus, I hold regular (weekly/bi-weekly) research cluster meetings, and one-to-one student-supervisor sessions whenever it is necessary, which are mainly teaching and discussion sessions.

5.1.4. Supervisors Have Different Standards

On more than one occasion, I have received feedback from my students during informal/formal conversations that suggest that I am perceived as hard to impress and meticulous when compared to others that they have met. I also received feedback that suggests that some supervisors had a softer approach to things compared to mine. The proof that supervisors have different standards usually play out during seminars when students compare their work with those of students from other supervisors.

In all cases, the comments about my meticulousness from students were never expressed harshly, at times they were mentioned as a form of commendation or relief that they were able to cope with certain academic demands that I had made. Usually, I do not let such comments go unattended. I handle this by making them understand that the basis for demanding such a high standard is to ensure academic rigor. In recent times, I have tried to improve and minimize this feeling among my students by ensuring that my critiques of students’ submissions are accompanied by suggestions that reveal my intention to help them. On some occasions, I have requested follow-up individual sessions with students so that we can go through my comments on their submissions to me where I take time to explain the basis for the critique and give advice on how it can be addressed. This is to ensure that they understand the basis for every critical comment that they received from me. I have received comments and testimonials from students where they referred to such moments of truth as very defining, and crucial for the success that they had eventually.

5.1.5. Mixing Academic Rigor and Humanity Will Work

Success will always be a product of hard work and commitment. As a supervisor, there must be an understanding that students operate in a social world where so many non-academic factors determine their performance. The need to meet certain prescribed standards for graduation requires that I demand a high standard of work from my students in terms of quality and rigor. On most occasions, the students have responded very well, particularly when they feel sufficiently supported. I have had many cases when a purely academic approach did not work. Rather giving support to the student by way of advice, and even allowing a period of academic inactivity, slowness, or study break to allow students to attend to important non-academic aspects of their life, and resume when at their best was what worked. From these experiences, I learnt that as a supervisor I need to find the balance between demanding quality work that meets expected standards, and the human aspect that relates to the social, economic, and human needs of my students. So far, this remains one of the most significant lessons in my supervision experience.

5.1.6. Some Life Coaching and Motivational Lifts Can Help Students

Because many non-academic factors contend with student performance during the postgraduate study, I found that engaging in some form of life coaching and giving motivational talks when the opportunity arises in informal conversations were also helpful to students. I discovered that getting into non-academic discussions that touch on general issues of life apart from academic work enhances the emotional, spiritual, and general wellbeing of the students, which have an attendant positive effect on their studies.

5.1.7. Students Need Help with Academic Writing

My experience is that students do not have what it takes to write good academic papers on their own without significant input from the supervisor, particularly when it is their first time. Mentoring students to write an academic paper for the first time can demand a lot of the supervisor’s time. However, when students have been mentored in the right way, they get better at academic writing which will also benefit the supervisor subsequently. This is because when so many students within a supervisor’s group can write well, the supervisor will be able to co-author many papers with the students from time to time.

5.1.8. Managing Critique from Peers during Students’ Seminars Could Be Challenging

Part of the postgraduate process is to have my students’ work shared with peers both within and outside the university to be reviewed and accessed. These periods when the work of my students such as seminar presentations and research proposals, or journal manuscripts have been subjected to critiques from colleagues proved to be useful and led to improvement of the work. It also enables me and the student to learn more. However, they were occasions when it brought about temporary confusion because certain issues that were raised were not clear cut. The way I have handled this is to seek more clarification from the source of the critique where it is possible to gain more clarity. On other occasions, it requires slowing down to do a rework so that the issues raised are addressed. At times, this may appear as a temporary setback in terms of projections on student progress. Yet, these instances helped me and the students involved to further develop the capacity to handle critique. Particularly, it helped the student to know that critique is an integral part of the scholarship process.

5.1.9. Student Needs to Be Trained on How to Handle Critique

I also found that students are ordinarily not good at handling critique. Usually, a student must have gained the consent of the supervisor before the student would submit his/her work for evaluation or peer-review. My observation is that students get worried when critiques come on a work that has been certified as good by their supervisor, who is supposed to be an expert. It could affect the confidence of some students if they are not adequately prepared to know that critique and peer-review are part of the academic process. Over the years, I have made it known to my students that critique is part of the process and that is why I want to be their most critical friend [22]. Thus, every fair critique that comes from others apart from me should be appreciated because it reveals gaps and weaknesses that escaped my attention as the supervisor. I also regularly share stories of how reviewed papers that got a verdict of major revision in the first reviewwere revised and got accepted eventually. Also, some papers that got rejected when they were sent to a particular journal, got reworked and submitted to other journals that accepted the papers eventually. This is to prepare them for experiences that await them when they have to publish their papers.

5.1.10. Mutual Trust Is Critical in Student-Supervisor Relationships

I also found that mutual trust is fundamental and critical in the context of student-supervisor relationships. In my interactions with students, I usually advocate for three levels of trust. I want my student to trust that (i) I am sufficiently knowledgeable to be a good guide to them if not, I would not have agreed to be their supervisor; (ii) I have their best interest at heart and want them to be successful; (iii) I am willing to help in every capacity that I can and will be honest when I am unable to help. In return, I want to trust that my students will give their best effort in the pursuit of the research study. My experience is that when mutual trust exists between me as a supervisor and a student in these outlined areas things have turned out well.

5.1.11. Students Love to Work with a Supervisor That Is Ready to Learn with Them

There were occasions when my students had very difficult problems to solve. It could involve trying to understand how to apply a new method/technique/concept that is relevant to their work. On many occasions, when informed of this as a supervisor, I do not have an immediate answer, but by maintaining a disposition to learn and investigate it together with them, we were able to find an answer. There were times, when we stumbled on the right path during brainstorming or discovered where the student can get additional help to solve the problem. Sometimes my experience helps me to find the right path faster after researching on the same subject which I then share with the student. At times, my offer to also investigate the problem alongside the student gingers them to find the solution faster and on their own without my direct input. I also discovered that my disposition to learn along with my students tend to make them want to share their thoughts and ideas with me as soon as they find something interesting. These instances provide me with ample learning opportunities to further develop my intellectual capacity.

5.1.12. Giving Up Is Not a Solution

Persistence is key particularly when a study seems not to be progressing as planned. Some students are tempted to give up or take the less efficient but easier route. At such moments, a student needs to be encouraged not to give up. I recall occasions when some journals requested that we do revisions 2 or 3 times before we were able to advance our article manuscript to the next stage. Considering the enormity of the revision required, I had occasions when students suggested that we give it up and abandon the ‘tough’ journal and choose a less difficult journal. As naïve as the suggestion may seem, I have been tempted to think that way too at times, but in all cases, by encouraging the students and by being persistent we were able to pull through. We endured to make the corrections, and eventually got the paper accepted. By doing this, the student was able to learn that doggedness and persistence are vital ingredients for a successful scholarship.

5.1.13. Students Get Help Elsewhere If They Feel That a Supervisor Is Not Doing Enough

Some students are willing to put up with the limitations of their supervisor just to make progress even when they feel underserved. I had been approached on some occasions by students who needed help and felt that their supervisors were not doing enough to help them. Some of these students were also from different institutions from where I worked. Some saw some publications authored/co-authored by me and felt I could assist them. Some came through referrals of academic colleagues who felt I could help to cover some gaps that the student’s supervisor is not willing to cover. It is very acceptable for students to seek help from other sources, but I found on some occasions that the students felt their supervisors would not be happy that they got help elsewhere. I found this very disturbing.

The lesson that I got from this is that if I fail to help my students sufficiently, they will seek assistance elsewhere with a feeling of being underserved. Thus, it is essential to give my students as much support as I can and to be open and honest to refer them to other sources of help that I am aware of. When I am unaware of other sources where they can be helped, I must give them the liberty to get help from wherever they can find it, and not feel guilty about it. This scenario of supervisors not been able to help students sufficiently is fairly common in African institutions, because of the dearth of core experts in certain areas. The computing field is particularly dynamic with new concepts and technologies coming up from time to time. A student may be interested in a particular topic that is relevant and contemporary such as blockchain technology, but to the limitation of personnel in the academic department, the student may get a supervisor who may be familiar with blockchain technology but not an expert in it. Thus, if the supervisor is not ready to learn and evolve his/her knowledge quickly during the period of supervision, it will affect the student adversely. For example, although I was trained as a computer scientist, I have supervised theses in the field of Information Systems. In such cases, I needed to evolve in my knowledge of Information Systems research and learn as quickly as I could during the early stages of the supervision to ensure that I can guide the students appropriately. Usually, by the time a supervisor supervises 1 or 2 projects in a field, he has become steadier and is better positioned to do even better as a supervisor of students with similar topics in the future.

5.2. What Are the Good Practices in My Supervision for the Past 12 Years? (R2)

In this section, I will highlight some of the good practices that have had a positive impact on my supervision in recent years. These were not things I knew at the early stages of my supervision but were a combination of things that I discovered in the course of my training as a doctoral student, postdoctoral fellow, observations from the practices of more experienced supervisors that I interacted with, and interactions with my students over the years. I found that investments in these good practices will yield good rewards.

5.2.1. Clarify the Student’s Motivation

Although all students have their motivation for pursuing a postgraduate program, at times some do not have the right motivation. Whenever I sense this, I usually call for a one-to-one session where the student is counselled and given a better orientation. Usually, this is done in my first or second meeting with a student. I found that addressing the issue of motivation early tend to help the student to get on the right footing. I have found this practice extremely beneficial to my students.

5.2.2. Help Students to Lay a Good Foundation

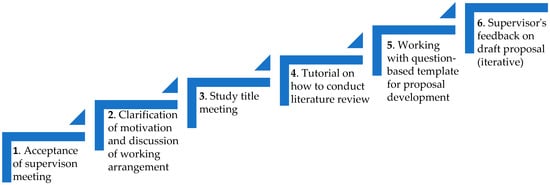

Over the years, I discovered that it is more rewarding for the supervisor to pay close attention to students at the foundational stages when they are trying to select a topic and title of study, work on their problem statement, aim and objectives of the study and their research questions. This agrees with the scaffolding approach to postgraduate supervision [14,20,22]. I give significant attention to ensure quality assurance when students are at the foundational stages of their studies. I discovered that students need more support at this stage than at other stages. This is because at the beginning of the study their understanding is growing, and they have more need of the supervisor’s experience to guide them in the right direction. When they fail to get it right at the beginning, it becomes problematic and more challenging to manage in the later stages. A supervisor needs to give sufficient support and scrutiny to ensure that students get the foundational aspects right. In my case, to do this effectively, I developed a question-based template (https://tinyurl.com/nr8csfe3) that guides my student on how to justify the title of their study, and derive the aim, problem statement, objectives, research questions of their study. I get the students to make their submissions on these foundational aspects to me based on the template and I give them my feedback based on this. We use the template to work on these foundational aspects iteratively until it reaches an acceptable level. At times, I do this in a participatory workshop that involves a group of students that are all at the foundational stages of their study. The student will only proceed to make changes to relevant aspects of their proposal document after these foundational aspects have been adjudged adequate by me. This is the quality assurance mechanism that I use. The supervision activities that I engage in with students during the foundational stages are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

My foundational Activities with Students During Supervision.

5.2.3. Encourage the Student to Do a Quality Literature Review

Most students that I have worked with were not skilled in the art of conducting literature reviews before enrolling for a master/doctoral program. This is a skill that is seldom taught at the undergraduate level in most African universities. Hence, students need to be trained on how to do literature reviews. I usually conduct tutorials for my students on how to search for literature on the web, and in relevant academic databases. I also encourage my students to attend seminars within the university that address the issue. A common problem for students particularly in developing countries is the inability to access papers that require a paid subscription. Fortunately, UA and UB where I have supervised are among the universities that have done well in the aspect of providing access to many relevant electronic academic databases. However, when students encounter papers that are relevant to their work but could not be accessed due to paywall restrictions, they are instructed on additional steps that could be taken to get the papers. These include reaching out to the author directly on ResearchGate or via their university email address, and also checking if free copies of such papers exist in open-access databases such as ArXiv, Base, CORE, Semantic Scholar etc. I also train my students on how to conduct literature-based research so that they can conduct systematic literature reviews, mapping studies, and even meta-analysis studies. I usually encourage a doctoral student to write a systematic literature review (SLR) that relate to the title of the thesis as an integral activity of their adopted research process. Some have responded well to this by publishing SLR papers while under my supervision [23,24,25]. This exercise gives the student wide exposure to the relevant literature and by so doing, they gain a solid understanding of the research landscape that they have to navigate.

5.2.4. Link Students with the Relevant Academic Communities and Networks

It is uncommon that a supervisor will be able to answer all the questions that the students have. Thus, it is wise to ensure that students are linked or connected to other sources where they can get help in the course of their studies. I have found this action very useful for my students and me. I ensure that my students can identify the top journals (mainly Q1 and Q2 journals) that focus on the topics of their research. Likewise, they must identify the leading researchers, and research centres/groups all over the world that are relevant to their study. Through this, the students could have access to inspiration and intellectual support beyond what I can provide. I also try to introduce them to international conferences that focus on the subject matter of their study. By doing this, the student will have access to many sources where they can be helped when the need arises.

5.2.5. Publish as You Go

An integral part of my supervision practices is to encourage students to publish regularly in the course of their research work. I picked up this practice from my doctoral supervisors that advised that I publish academic journal papers while working on my doctoral study [26,27]. I have replicated this in my supervision practices while working with students as a supervisor [28,29,30,31,32]. This has yielded benefits in terms of deepening students’ understanding of their ongoing work and gaining a sense of progress and achievement in their studies. The feedback from review reports from subject-matter conferences, and journals have helped to improve the quality of the theses that I have supervised. I encourage my students to make the first attempt to write a paper from their work after they have passed the research proposal examination. These position/idea papers are submitted to doctoral symposiums, workshops, or conferences as short papers. The feedback received from expert reviewers helped to improve our perspectives of the ongoing studies involved. Students are also encouraged to publish their preliminary results and ongoing work in workshops and conferences, before publishing a full research article where the full study results are presented. These paper writing and publishing activities help students to evolve in the understanding of their ongoing research work, and understanding of the peer-review process which contributes to their overall academic development.

5.2.6. Aim to Get Published in Good Journals

The two universities where I have supervised so far require that a student should have academic publications from the thesis as one of the requirements for graduation. A failure to meet this requirement could mean that the student will spend extra time which is not desirable for the student and supervisor. An easy option could be to target lowly rated accredited journals. Usually, with such journals, the chances of getting a paper accepted are higher, but the reputation of the journal could be very low. I do not encourage this with my students because, I believe the doctoral research (particularly) for most persons, could turn out to be the most elaborate form of research that someone would ever do except those that take to academia later in life where they may be able to take on more research challenges. Thus, the findings from a doctoral work in which enormous intellectual effort has been invested for 3-years or more should be published in decent and reputable journal outlets that will make everyone proud even years after the degree has been earned. I encourage my students to publish their work in reputable journals (Q1 and Q2 rated journals only) and conferences, which could boost their chances of winning grants, fellowships, and other academic opportunities in the future. The risk of not graduating on time due to the inability to fulfil the publication requirement for graduation is mitigated by the fact that I encourage my students to publish several papers from their ongoing work. Thus, even if there is a delay in the process of getting published in a particular journal because they started publishing early, that particular delay will not prevent them from graduating on time. They would have met the minimum criteria for publication to be able to graduate. This approach gives them the confidence to follow through with the peer-review process of top journals which could be prolonged at times.

5.2.7. Let Students Benefit from International Exposure

I explore opportunities for international exposure for my students. This is mostly through short-term exchanges in the developed countries. I encourage them to look for national or international grants/fellowships (e.g., TWAS, and Fulbright fellowships) that can support short research visits. The has been beneficial over the years because it helps to improve the quality of work done, and facilitated continual research collaboration with the international supervisors that hosted the students. Although lately, this has been hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic, from experience, I noted that the students that leveraged on such opportunities were able to complete their work within a shorter time, and had more quality in their work compared to what could have happened if they did not have international exposure. This is particularly important for doctoral students, hence supervisors, and students must explore available opportunities that can facilitate international exposure.

Another great experience that students need to have is making paper presentations in subject-matter international conferences. There is a world of difference between making a paper presentation in a general-purpose conference or multi-conference where there may be few or no experts on a student’s work and subject matter conferences where experts on the topic abound. Supervisors must ensure that students have the opportunity to present their work to unfamiliar audiences that have core expertise and interest in the topic of the student’s work. From my experience, the student and the supervisor stand to gain a lot from the comments and feedback from such forums. They will also have opportunities to discover potential research collaborators. I remember quite well that during my doctoral study, it was the feedback that I received from a doctoral symposium session at an e-tourism conference (ENTER 2008) in Innsbruck, Austria which I attended together with the supervisor that gave me a breakthrough in my doctoral work. My doctoral thesis was titled “A Software Product Line Approach to Ontology-based Recommendations in E-Tourism Systems”. Thus, the ENTER 2008 was a relevant subject matter conference for my study, where I met several e-tourism experts who were able to relate accurately and intellectually with my study and gave insightful feedback. I have continued to replicate this same practice of exposing students to subject matter conferences hosted by the IEEE and ACM, Lecture Notes in Computer Science Series (LNCS), and computing journals that are listed in Scopus, the Journal Citation Report (JCR) of Clarivate Analytics, and DBLP: Computer Science Bibliography.

5.3. What Are the Things to Avoid Based on My Experiences over the Past 12 Years?

In this section, based on my reflection, I will share some of the things that I have learnt to avoid in the process of supervision.

5.3.1. Directing and Not Supervising

To meet up with certain evaluation requirements for academics such as promotion evaluation or academic rating evaluations, there is a tendency for a supervisor to over-direct the student so that the work gets done quickly. This unfortunately erodes the capacity of a student to do independent work. Autonomy and independence are virtues that students must acquire in the process of postgraduate education. While a supervisor could be more directional while relating with a master’s student, a doctoral student should be more independent. Allowing a student to take ownership by working independently and developing autonomy will result in greater capacity development of the student [20]. I had occasions where I realized that I over directed a few students such that at the later stages when I wanted them to be more independent, they struggled. Since I was not prepared to keep on directing all the way, I needed to reset my mode of interaction with them and rewrite the rules. For example, there was an occasion when I worked on a paper with a student for the first time. The first review outcome was not so favorable and a major revision was requested by reviewers. Because of the zeal to get the paper accepted, I ended up overdirecting the student on what needed to be done. I did not realize the adverse effect of this until it was time to work on a second paper after the completion of the thesis. I discovered that the student was confused about many things and did not demonstrate sufficient learning from the first episode which got me worried. The way I solved the problem was to reset my mode of interaction with the students concerned by being patient and ensuring that he worked independently by using the first paper as a sample with minimal input from me to get to an expected level. This meant that we could not submit the second paper until six months after the thesis had been completed. I found that it is better to not answer all questions posed by students but to encourage them to figure certain things out on their own with minimal guidance. This has proved beneficial to me and my students on many occasions. Most of the time, the student will find the answers on their own and come back with excitement on what they found, which also educates me further because I have not read as much as they did on the subject matter. At the time when I did not know better and over directed students, I found that the students mixed vital opportunities to understand the key concepts thoroughly which was not my intention.

5.3.2. Having a Rigid Style

In [22], the author highlighted three possible roles that a supervisor can play during supervision. These are facilitator, director, and critical friend. I believe that at different times during supervision, the supervisor must be ready to switch roles and adapt to the needs of the student as the occasion demands. Students have different expectations of their supervisors. Some students cope well with a less-involved approach, while others need active and structured support to succeed [33]. A student once left me because it was difficult to keep up with my regular schedule of weekly/bi-weekly group meetings. The student preferred to work independently and get in touch with me only when it was necessary. However, I did not favor the proposal because from my previous experiences with students it seemed like the student just wanted to take a back seat and not take the work seriously. We parted ways, and the student went to another supervisor. With time, I observed that the student made good progress with the new supervisor who was comfortable with the same work arrangement that I rejected. With the benefit of hindsight, I realized that I did not do enough to know the student better to have the required level of trust and make a better judgement on the case but acted based on my previous experiences with other students. The lesson is that being flexible and adaptable could be beneficial to students than being rigid. With this, I learnt that while principles should be fixed/rigid, styles must be flexible and adaptable. In this case, while my principle remains to demand ownership, hard work, and commitment from my students, the work arrangement and nature of interaction should be flexible and adaptable to the specific situation of different students.

5.3.3. Not Giving Enough Time and Support to Students

Students need to feel supported in their postgraduate journey. My interaction with students reveals that some students do not feel sufficiently supported by their supervisors. This made me decide to adequately support my students. As I reflect on comments from students through various mediums such as words of appreciation that were expressed, written statements in the acknowledgement section of their completed theses, and testimonials, I am more convinced that it is a good thing to ensure that students feel supported during supervision. Most of the students that I supervised want to do their doctoral studies with me, while the doctoral graduates want to be my postdoctoral fellows. I have also seen cases where some students do not want to have anything further to do with their previous supervisors because they felt underserved.

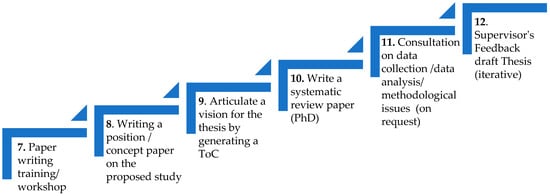

5.4. My Supervision Process

The set of good practices outlined in Section 5.2 typically defines the process that I have adopted for my supervision. After the foundational support that is provided in the early stages (Figure 1). Students are further supported albeit in a more withdrawn way after they have passed their proposal examination. Post-proposal, I engage more with students in groups through workshop and tutorial sessions. The activities in Figure 2, which are listed as #7–#12 are initiated as workshop or seminar sessions for specific student groups. Each student will then apply what they have learnt by writing a paper which will be reviewed by me, with feedback provided. The one-to-one interaction with individual students will continue until the paper is submitted. Any need for consultation on data collection, data analysis, or methodology (#11) will have to be requested by a student if it is deemed necessary. Students receive feedback and inputs on their draft theses when it is submitted to me for review and feedback. This is also an iterative process until acceptable quality is attained from my perspective as the supervisor.

Figure 2.

An overview of my activities with students after the proposal stage.

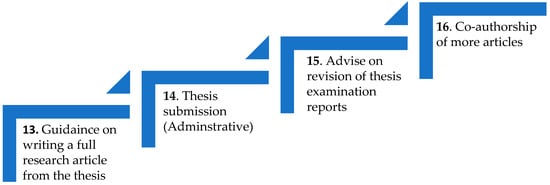

The activities in the final stages (Figure 3) entail getting the student to write at least 1 full research article from the study and getting feedback on the draft thesis before submission of the thesis for external examination. After the external examination, advice may also be provided as necessary based on the comments of the external examiners so that an adequately revised thesis can be submitted by the student. After the submission of the thesis, I am also involved in the co-authorship of more research articles from the study with the student.

Figure 3.

An overview of my activities during the final phases of supervision.

6. Discussion

As I reflected on the good practices of my postgraduate supervision and the things that I must avoid, I also sought to identify (i) the influences that have stimulated me to adopt my good practices; (ii) how I have evolved in the application of the good practices; and (iii) how my good practices can be scaled for replication by others. The discussion in this section will focus on these 3 themes.

6.1. The Influences That Stimulated My Good Practices

I identified four critical factors that have influenced my supervision practices. These are:

- (i)

- The influences of supervisors and mentors that I had worked with.

I discovered that my supervision practices at the early stages were significantly influenced by experiences during my academic training at the masters, doctoral, and post-doctoral stages [15]. Over time, I have also combined these inherited practices with other practices that I picked up through my interactions with more experienced colleagues, and my experiences gained through working with different types of students over the years. All these, coupled with my fundamental pedagogical philosophy and principles have been aggregated, contextualized and integrated into my supervision practices. I will argue that like me, many supervisors also have some inherited ideals included in their supervision practices. This could be good or bad depending on the kind of influence that they were exposed to during their training. Some of the good practices that I inherited include publishing academic papers continually from an ongoing thesis, motivating students to participate in subject-matter conferences to get good feedback and international exposure, and going on short research visits. Thus, by entrenching these inherited practices in my supervision process, my students who will become supervisors in the future will hopefully pass it over to their supervisees. I believe wrong practices imbibed from poor and abusive supervision can equally be passed down to others if not checkmated [5]. Higher institutions in Africa must do more to entrench good supervision practices so that it becomes the norm and not the exception [34].

- (ii)

- The constraints in the environment of my supervision

My supervision practices have also been influenced by the need to respond to some of the challenges that I had to deal with regularly, and some of the constraints in the environment where I did the supervision. My reflections on practices and observations from interaction with students reveal that much is expected from a supervisor in the African continent despite the constraints that supervisors have to contend with [15]. Postgraduate students in Africa also have many challenges of their own such as a lack of funding, and advanced research resources [3]. For example, few postgraduate students are supported with external research grants. In UA, virtually all the students are self-sponsored, while in UB, while few South Africans have access to government bursary, the international students are mostly self-sponsored. Since students have to spend the minimum time required and work within available resources, the study must be scoped appropriately within the available budget and resources. If care is not taken, this could mean that the scope and quality of work may not be so competitive when benchmarked with international standards. However, the top journals in the field where every ambitious researcher wants to publish will not lower their standards just because a manuscript is coming from Africa where most researchers are not as well-resourced in terms of infrastructure and resources. Thus, getting into strategic collaborations with international colleagues who may be able to help to cover some gaps through their role in the collaborative project would be a good thing. This could help to supplement available resources and raise the quality of work to a higher level. In my supervision, I have benefitted from collaborative supervision with international colleagues which have been mutually beneficial to me, the student and the collaborator. This has also helped to raise the profile of the studies concerned.

- (iii)

- The recurrent learning needs of students

I noticed certain problems are recurrent with different cohorts of students that I supervise. Many students tend to struggle with academic writing, literature review, and the use of software tools to support their writing [14]. The same type of problem that was addressed for a student at the early stages of the study must be repeated for a new student that will show up one year later. For instance, I have had to deal with students that require more structured support in academic writing either because their first language of learning was not English or was not just cut out for academic writing. Thus, I decided to integrate the solution to these recurrent problems into the workflow of my supervision process. To do this, I developed a paper writing template that can be shared with students to guide them in paper writing (https://tinyurl.com/nr8csfe3). I made recorded video lectures on these aspects which could be shared with students that are challenged in these areas. I also have a collection of other learning resources by other scholars on these aspects which can be shared with students. Therefore, whenever a student needs support in any of these recurrently problematic areas, there are learning resources that can be used to support the student. After watching the videos, there could be a follow-up session to answer questions that need clarification or further explanation. This is a good practice that I came out of the need to address the challenges encountered during supervision.

Thus, the challenges that supervisors in the African context are faced with should not be a reason for discouragement but be seen as opportunities to create a contextualized solutions that are relevant to the environment in which supervision is done [35].

- (iv) Positive feedback from supervisees

Another factor is the good feedback from students that have been supervised by following these practices. The feedback is particularly encouraging in terms of quality of work done, papers published from the theses, and what the students are capable of doing on their own after the supervision. The majority of my students have enjoyed the process and attested that they will gladly replicate the same process if they have to supervise students. Some appreciated what they learnt from the supervision process but will not go into academics but other professional vocations. For example, some of my supervisees in their written testimonials have acknowledged their excitement at (i) getting 1 or 2 papers from their theses published in Q1 journals that have good impact factors [25,29,30]; (ii) becoming persons that could report their research findings in outstanding publication outlets, which they could not previously imagine until they came under my supervision; (iii) a better understanding of the research process which stimulated them to enroll for a doctoral study after I supervised their master’s degree; (iv) commendations of their work by external examiners; and (v) general appreciation of knowledge gained in the research field that have fetched them fellowship awards and employment opportunities; (vi) many are have become supervisors in the universities where they work, and have acknowledged the positive impact of replicating some of the practices they learnt from my supervision.

Therefore, it is good for supervisors to identify practices that have yielded good results with regards to expected learning outcomes, positive feedback from students and peer evaluations, testimonials, and commendations and acknowledgements that are received from specific supervision activities so that they sustain them and find ways to scale them to produce a greater impact. For example, my students have always commended my research capacity building activities such as tutorials on how to search for literature on the web, and conduct literature review (Figure 1—#4). In the tutorial, students are taught how to search the web by using advanced search features of search engines and repositories like Google Scholar, Scopus to obtain better search results. They also feel practically empowered to know how to create query alerts on academic databases such as Scopus and Google Scholar so that they can be notified via email whenever new papers that pertain to their ongoing work become available in these databases. In Africa, due to resource limitations, the university library may not have subscribed to some elite academic databases, which makes it difficult for students to access some papers that require a paid subscription. My students appreciate getting informed about free and open academic repositories such as CORE (https://core.ac.uk/), Semantic Scholar (https://www.semanticscholar.org), BASE search engine (https://www.base-search.net/) and the likes where a free versions of a paper that is behind a paywall could be found. My workshops on the use of question-based templates for proposal writing (Figure 1—#5); paper writing (Figure 2—#7, #8, #10); and use of software tools for document management, selection of where to publish are examples of key capacity building activities that my students find very valuable. The good feedback from students and the good attendant results have reinforced my commitment to sustaining these practices.

6.2. My Evolution in the Application of Good Practices

The manner and intensity of application of my supervision practices have not always been the same. It has gone through series of refinements and improvements as I attain more maturity as an academic. Since 2018, for example, I have had access to more resources in terms of grant awards, a larger pool of students to supervise, working with more international collaborators, and support from postdoctoral fellows. This has positively affected my supervision practices. I have been able to promote more collective learning among my students by getting students to review one another’s proposals, critique each other in our group sessions, and delegate critical reading and even co-supervision to postdoctoral fellows. This is coupled with inviting my research collaborators to give capacity building lectures to my students. All of these have contributed positively to my postgraduate supervision process.

As recommended by [15], I have also evolved in my general knowledge of supervision by taking a training course on postgraduate supervision, and attended workshops that were organized for supervisors. These training workshops have provided opportunities to compare notes with other supervisors to learn about their good practices. For example, the concept of collective learning and peer-learning within the group of students under my supervision was picked out from a colleague that I met at a workshop. I found that students learnt a lot from this because it helps them to develop the skills for critique and evaluation of academic writings. Another thing of interest was the discovery of journals that publish articles on the topic of supervision, such as the International Journal of Doctoral Studies, Journal of Higher Education and others, which I did not know about previously. I have learnt about good supervision practices by reading articles from these journals. All these factors have helped to advance my supervision practices positively.

Thus, it is essential for supervisors to not only identify good practices and adopt them, but they also need to evolve continually in their supervision practices by finding what they could do better, what needs to change, things to add, and things to stop.

6.3. Scaling My Good Practices for Adoption by Others

As mentioned earlier, my supervision practices were a product of discoveries that were gained from different sources, and my unique experiences from interactions with students that I supervised over the years. However, through the autoethnographic account of my supervision in this paper, I am seeking to popularize these good practices so that other supervisors in Africa, particularly those in the computing disciplines that have not adopted these good practices could emulate them wholly or in part to enhance their supervision practices. In [17], it was recommended that writing autoethnography can help to promote good practices in supervision. Thus, by this paper, my good practices can become more widespread to improve the quality of supervision of many African-based supervisors. It may not be possible to replicate these practices in all settings in Africa due to resource limitations and other contextual factors. I have been able to execute the outlined good practices in my supervision workflow many times, but not all times. For example, I have supervised students to graduation that fell short of my desire to get more papers published from their theses. For some, after they met the minimum publication requirement for graduation, they were not keen to publish more papers. Some students published more conference papers instead of journal articles even though the potential to do better was there. On my part, I could not encourage them to push further after the supervision officially ended. They were also those that surpassed the minimum in terms of publications and with whom I developed continuous research collaboration even after the supervision ended. Thus, the outlined good practices could be used as a framework by other supervisors which could be integrated into their supervision practices. These practices align with recommended best practices according to [34,35]. Based on my experience, I am convinced that these practices will yield good outcomes more times than not in Africa, and other developing countries.

6.4. Limitations

This paper presents an autoethnography of my experience of postgraduate supervision in two African universities. The lived experience that was the basis of reflection is limited to two universities where the supervision took place. Ordinarily, this would appear to weaken the potential for generalization of the findings of the study. However, the responsibilities of a supervisor are the same in most climes, which means that although the paper is based on a personal reflection on supervision that was done in specific educational contexts in Africa, other supervisors from other contexts can still relate to the challenges of postgraduate supervision, and the good practices that were presented in this paper. Some of the good practices that are canvassed in this paper were influenced by the universities where the supervision took place. Some of the challenges that I experienced may not exist in some other universities, which would make some practices to be unnecessary. On the other hand, some practices may not be practicable in some universities that are not as well-resourced as the ones where I did my supervision. In such cases, it will be good for other supervisors to focus only on the things that are practicable in their context and overlook details that are not relevant. This will help them to derive some value from the autoethnographic account that is presented in this paper.

7. Conclusions

Supervision is a challenging and delicate adventure where the quality of motivation, the quality of intellectual investments of the student and the supervisor, and the quality of the relationship between the student and the supervisor determines the outcome [15,20,33,36]. Supervision is not a concept that can be taught like a subject but is more of a skill that is acquired through lifelong learning and practice. Thus, supervisors must regularly engage in self-reflection as a critical step to engender improvement of their practices. In this paper, I have reflected on my journey as a supervisor in two African universities which were designated as UA in Nigeria, and UB in South Africa. Generally, my experiences of supervision in these two universities have been very positive. However, my adopted practices of supervision which have evolved and will continue to evolve have been influenced by lessons picked from my supervisors, mentors that I have interacted with, and my own experiences from interactions with students that I have supervised. Another major influence was the challenges and constraints that exist in the environment where I have supervised. Although this autoethnographic account is personal, I believe it will be relevant to other supervisors that supervise in Africa and other developing countries because the problems mentioned in this paper are fairly common and recurrent in many developing countries. Thus, I hope that this personal reflection on my supervision will serve a useful purpose for other supervisors and contribute to a general improvement of the supervision culture, particularly in African institutions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Rumney, P. Readerships/Professorships–How to Get There. The Legal Academic’s Handbook. 2016. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4hp3eekv (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Lemmer, E.M. The Postgraduate Supervisor Under Scrutiny: An Autoethnographic Inquiry. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2016, 12, 78–97. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan, C.W. Do benevolent and altruistic supervisors have higher postgraduate supervision throughput? The contributions of individual motivational values to South African postgraduate supervision throughput. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2020, 34, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Rooij, E.; Fokkens-Bruinsma, M.; Jansen, E. Factors that Influence PhD Candidates’ Success: The Importance of PhD Project Characteristics. Stud. Cont. Educ. 2021, 43, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meng, Y.; Tan, J.; Li, J. Abusive supervision by academic supervisors and postgraduate research students’ creativity: The mediating role of leader–member exchange and intrinsic motivation. Int. J. Lead. Educ. 2017, 20, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khene, C. Supporting a humanizing pedagogy in the supervision relationship and process: A reflection in a developing country. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2014, 9, 073–083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, J.; Anderson, V.R.; Morgaine, K.C.; Thomson, W.M. Effective and ineffective supervision in postgraduate dental education: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 17, e142-50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, A. Living without a Mobile Phone: An Autoethnography. In Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Hong Kong, China, 9–13 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C.; Adams, T.E.; Bochner, A.P. Autoethnography: An overview. Hist. Soc. Res. 2011, 36, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, L. Personal ethnography. Commun. Monogr. 1996, 63, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, D.; Hodkinson, P. Can there be criteria for selecting research criteria?—A hermeneutical analysis of an inescapable dilemma. Qual. Inq. 1998, 4, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M. Autoethnography: Critical Appreciation of an Emerging Art. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2004, 3, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, U. A confessional account of an ethnography about knowledge work. MIS Q 2000, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djohy, G. Socio-technological enrollment as a driver of successful doctoral education. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2019, 14, 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sefotho, M.M. Carving a Career Identity as PhD Supervisor: A South African Autoethnographic Case Study. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2018, 13, 539–557. [Google Scholar]

- Ramukumba, M. Using mobile devices in supervision of graduate research in distance education: A personal journey. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]