The Educational Technology of Monological Speaking Skills Formation of Future Lawyers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, R.H. Fostering students’ workplace communicative competence and collaborative mindset through an inquiry-based learning design. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, V.; Polyezhayev, Y.; Bezkhlibna, A. Communicative competences in enhancing of regional competitiveness in the labour market. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 2018, 4, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M.; Popova, N.; Shestakov, K.; Harrison, L. Out-of-class online language learning partnership between Russian and American students: Analysis of tandem project results. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2015, 529, 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Almazova, N.; Krylova, E.; Rubtsova, A.; Odinokaya, M. Challenges and opportunities for Russian higher education amid covid-19: Teachers’ perspective. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 368. [Google Scholar]

- Bylieva, D.; Lobatyuk, V.; Safonova, A.; Rubtsova, A. Correlation between the practical aspect of the course and the e-learning progress. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, N.I.A.; Noordin, N.; Razali, A.B. Improving oral communicative competence in English using project-based learning activities. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2019, 12, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargie, O.; Dickson, D.; Tourish, D. The world of the communicative manager. In Communication Skills for Effective Management; Palgrave: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrizzato, S.; Goracci, G. English for nursing: The importance of developing communicative competences. J. Teach. Engl. Specif. Acad. Purp. 2013, 1, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Dumina, E.V. K voprosu o formatah professional’nogo inoyazychnogo obshcheniya v trudovoj deyatel’nosti sovremennogo yurista. Vestn. Mosk. Gos. Lingvisticheskogo Universiteta Obraz. Pedagog. Nauki. 2018, 3, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J.; Widodo, H.P. On the design of a global law English course for university freshmen: A blending of EGP and ESP. Eur. J. Appl. Linguist. TEFL 2018, 7, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Northcott, J. Teaching legal English: Contexts and cases. In English for Specific Purposes in Theory and Practice; Belcher, D., Ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009; pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yalaeva, N.V. Mezhkul’turnaya kompetenciya v podgotovke yuristov. Vestn. Ural. Inst. Ekon. Upr. Prava 2014, 2, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lyskova, M.I. Prakticheskie aspekty inoyazychnoj podgotovki sotrudnikov organov vnutrennih del v sisteme dopolnitel’nogo professional’nogo obrazovaniya. Nauchno-Metod. Elektron. Zhurnal Koncept 2014, 1, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Vikulina, M.A. K voprosu o rannej professionalizacii studentov-yuristov pri obuchenii inostrannomu yazyku. Vestn. Mosk. Gos. Lingvisticheskogo Universiteta. Obraz. Pedagog. Nauk. 2015, 16, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, M. A beginner’s course in legal translation: The case of culture-bound terms. ASTTI/ETI 2000, 2, 357–369. [Google Scholar]

- Popova, N.; Petrova, O. English for law university students at the epoch of global cultural and professional communication. Probl. Zakon. 2017, 138, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kurchinskaya-Grasso, N.O. Osobennosti i osnovnye harakteristiki yuridicheskogo anglijskogo yazyka. Litera 2020, 12, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelianova, T.V. Fundamentals of lawyers’ professional English-language intercultural interaction. In Proceedings of the INTCESS 2021 8th International Conference on Education and Education of Social Sciences, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 18–19 January 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, N.V. Podgotovka budushchih yuristov k delovomu inoyazychnomu obshcheniyu v teorii i praktike vysshego obrazovaniya. Izv. Saratov. un-ta. Nov. seriya. Seriya Filosofiya. Psihologiya.Pedagogika. 2013, 13, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmetshina, Y.U.V. Formirovanie pravovoj kul’tury studenta yuridicheskogo vuza sredstvami anglijskogo yazyka. Innov. podhody Nauk. Obraz. Teor. Metodol. Prakt. 2017, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, A.M.; Dennis, A.R.; McNamara, K.O. From monologue to dialogue: Performative objects to promote collective mindfulness in computer-mediated team discussions. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambacher, E.; Ginn, K.; Slater, K. From serial monologue to deep dialogue: Designing online discussions to facilitate student learning in teacher education courses. Action Teach. Educ. 2018, 40, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K. The cultural construction of memory in early childhood. In Handbook of Culture and Memory; Wagoner, B., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, P.; De Ruysscher, C. From monologue to dialogue in mental health care research: Reflections on a collaborative research process. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glotova, Z.H.V. Formirovanie Professional’noj Inoyazychnoj Kompetentnosti u Studentov-Yuristov v Processe Obucheniya. Ph.D. Thesis, Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, Kaliningrad, Russia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel, K.; Buss, R.; Foulger, T.S.; Lindsey, L. Infusing educational technology in teaching methods courses: Successes and dilemmas. J. Digit. Learn. Teach. Educ. 2014, 30, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, G. Technology and the future of language teaching. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2018, 51, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murati, R.; Ceka, A. The use of technology in educational teaching. J. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 197–199. [Google Scholar]

- Denisov, V.N.; Kiryushkina, T.V. Kompleksnyj podhod dlya dostizheniya kommunikativnoj celi obucheniya inostrannomu yazyku v neyazykovom vuze. Vestnik SGYUA 2016, 5, 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Borisova, N.V. Obrazovatel’nye Tekhnologii kak ob Ekt Pedagogicheskogo Vybora v Usloviyah Realizacii Kompetentnostnogo Podhoda; Issledovatel’skij Centr Problem Kachestva Podgotovki Specialistov: Moscow, Russia, 2010; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhina, T.G. Aktivnye i Interaktivnye Obrazovatel’nye Tekhnologii (Formy Provedeniya Zanyatij) v Vysshej Shkole; NNGASU: N. Novgorod, Russia, 2013; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Masalimova, A.R.; Levina, E.Y.; Platonova, R.I.; Yakubenko, K.Y.; Mamitova, N.V.; Arzumanova, L.L.; Grebennikov, V.V.; Marchuk, N.N. Cognitive simulation as integrated innovative technology in teaching of social and humanitarian disciplines. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 4915–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnieli-Miller, O. Reflective practice in the teaching of communication skills. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, H.C.; Bullock, O.M. Using metacognitive cues to amplify message content: A new direction in strategic communication. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2019, 43, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, K.; Daiute, C. The process of self-regulation in adolescents: A narrative approach. J. Adolesc. 2017, 57, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronova, L.; Karpovich, I.; Stroganova, O.; Khlystenko, V. The adapters public institute as a means of first-year students’ pedagogical support during the period of adaptation to studying at university. In Proceedings of the Conference “Integrating Engineering Education and Humanities for Global Intercultural Perspectives”, Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 25–27 March 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, R.A.; Schwartz, B.M. Optimizing Teaching and Learning: Practicing Pedagogical Research; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment–Companion Volume; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, Germany, 2020; Available online: www.coe.int/lang-cefr (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Fahrutdinova, A.V.; Grebcova, S.V. Kriterii ocenki rechevoj aktivnosti na zanyatiyah po inostrannomu yazyku v vysshih uchebnyh zavedeniyah rossii i zarubezhom. Uchenye Zap. Kazan. Gos. Akad. Vet. Med. im. NE Baumana 2014, 219, 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Odinokaya, M.; Krepkaia, T.; Sheredekina, O.; Bernavskaya, M. The culture of professional self-realization as a fundamental factor of students’ internet communication in the modern educational environment of higher education. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokoe, E. Simulated interaction and communication skills training: The “conversation-analytic role-play method”. In Applied Conversation Analysis; Antaki, C., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, N.H.; Halim, M.F.A.; Kamarulzaman, S.Z.S. The effectiveness of storytelling in enhancing communicative skills. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 18, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, E. Techniques developing intercultural communicative competences in English language lessons. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 186, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odinokaya, M.A.; Barinova, D.O.; Sheredekina, O.A.; Kashulina, E.V.; Kaewunruen, S. The use of e-learning technologies in the Russian University in the Training of Engineers of the XXI century. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 940, 012131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinciu, A.I. Adaptation and stress for the first year university students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 78, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, N.D.; Sahin, H.; Nazli, A. International medical students’ adaptation to university life in Turkey. Int. J. Med Educ. 2020, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linz, D.; Penrod, S.; McDonald, E. Attorney communication and impression making in the courtroom. Law Hum. Behav. 1986, 10, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.G.; Kwon, S.; Park, H.J. The influence of life stress, ego-resilience, and spiritual well-being on adaptation to university life in nursing students. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, A.; Pazukhina, S.; Yakushin, A.; Ponomareva, T. A study of first-year students’ adaptation difficulties as the basis to promote their personal development in university education. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2018, 11, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, M.; Snowball, J.D. Where angels fear to tread: Online peer-assessment in a large first-year class. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

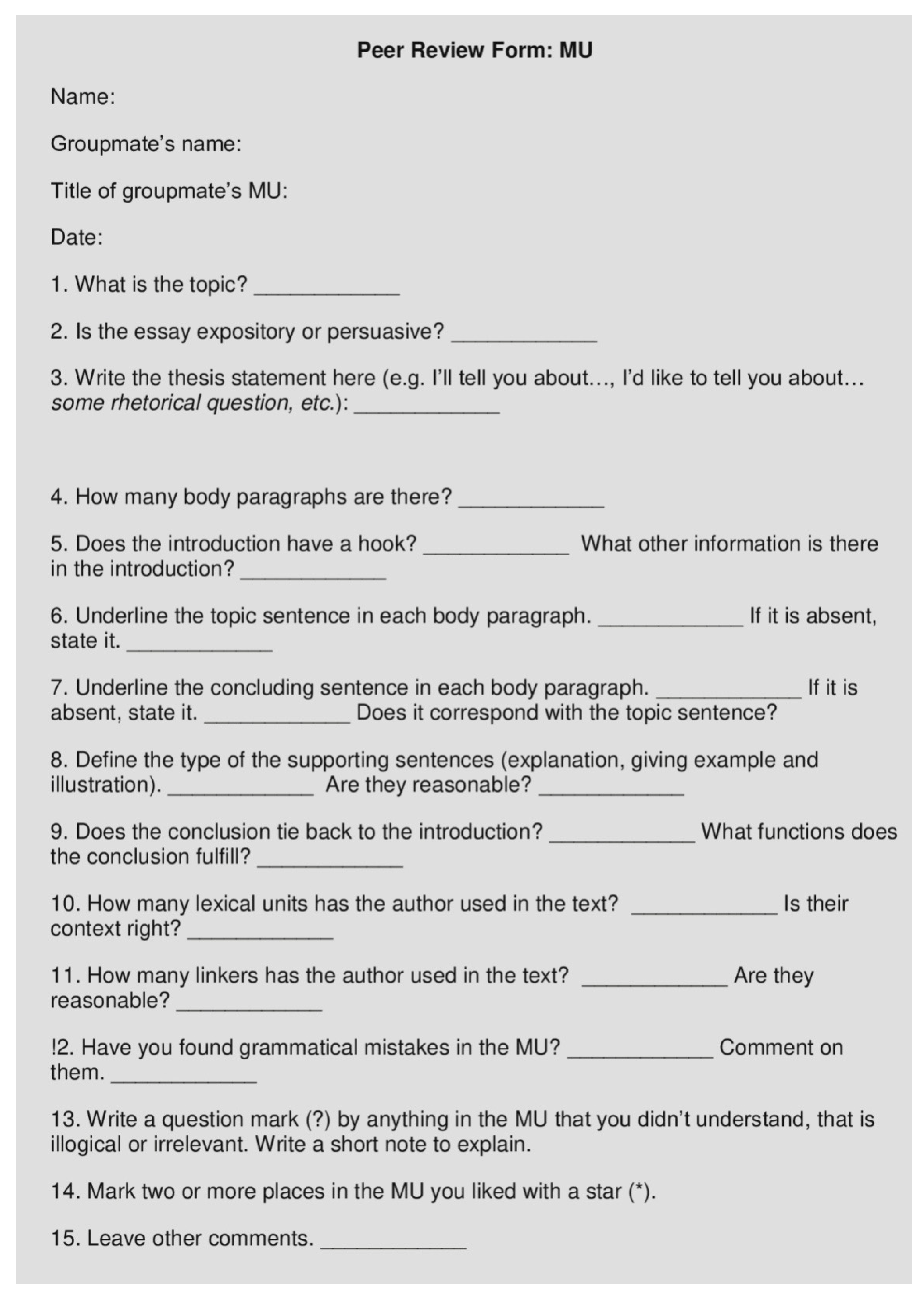

- Sheredekina, O.A. Metod vzaimnogo recenzirovaniya v formirovanii sposobnosti studentov mnogoprofil’nogo vuza k inoyazychnoj rechi. Vopr. Metod. Prepod. v Vuze 2020, 9, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № | Aspects | 2 Points | 1 Point | 0 Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Content and organisation of MU | The topic is elaborate and all MU elements fully correspond with the topic. | Content discrepancy or lack of one structural element. | Content discrepancy or lack of two or more structural elements. |

| 2. | Vocabulary | The use of 25 + lexical units of the total amount (47). NB. The lexical unit is considered to be correct only if it is pronounced right. | The use of 16–24 lexical units. | The use of 15 lexical units and less |

| 3. | Coherence | All structural elements of MU are coherent. The use of 10 linkers and more. | The use of 6–8 linkers. | The use of 5 linkers and less. |

| 4. | Grammar: grammatical mistakes | No more than 4 grammatical mistakes are allowed. | 5–6 corrected grammatical mistakes are allowed. | More than 6 grammatical mistakes are made. |

| 5. | Fluency and pronunciation, presentation of MU | The speech is fluent. Pronunciation corresponds to the norm. The speaker relies on nothing while performing the utterance. | The speech is rather fluent. Some phonetic and prosodic mistakes are made. The speaker relies on his plan or notes. | The speech is slow with lots of pausing; the same words are often repeated. The speech contains many phonetic and prosodic mistakes. The speaker relies on the text of MU. |

| Stage № | Arithmetic Mean | Mean Deviation | Deviation Squares | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-Group | E-Group | C-Group | E-Group | C-Group | E-Group | |

| I | 6 | 7.5 | − 0.63 | − 1.38 | 0.3969 | 1.9044 |

| II | 6 | 9 | − 0.63 | 0.12 | 0.3969 | 0.0144 |

| III | 7 | 9.5 | 0.37 | 0.62 | 0.1369 | 0.3844 |

| IV | 7.5 | 9.5 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 0.7569 | 0.3844 |

| Total | 26.5 | 35.5 | − 0.02 | − 0.02 | 1.6876 | 2.6876 |

| Mean | 6.63 | 8.88 | ||||

| tcr | |

|---|---|

| p ≤ 0.05 | p ≤ 0.01 |

| 2.45 | 3.71 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almazova, N.; Sheredekina, O.; Odinokaya, M.; Smolskaia, N. The Educational Technology of Monological Speaking Skills Formation of Future Lawyers. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070330

Almazova N, Sheredekina O, Odinokaya M, Smolskaia N. The Educational Technology of Monological Speaking Skills Formation of Future Lawyers. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(7):330. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070330

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmazova, Nadezhda, Oksana Sheredekina, Maria Odinokaya, and Natalia Smolskaia. 2021. "The Educational Technology of Monological Speaking Skills Formation of Future Lawyers" Education Sciences 11, no. 7: 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070330

APA StyleAlmazova, N., Sheredekina, O., Odinokaya, M., & Smolskaia, N. (2021). The Educational Technology of Monological Speaking Skills Formation of Future Lawyers. Education Sciences, 11(7), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070330