Teaching Performance of Slovak Primary School Teachers: Top Motivation Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim and Research Problems

- WH1—The motivation of primary school teachers in Slovakia will not change over time;

- WH2—The motivation of primary school teachers in Slovakia will change over time and in relation to gender.

2.2. Description of the Research Sample

2.3. Research Procedure

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vnouckova, L.; Urbancova, H.; Smolova, H. Approaches to employee development in Czech organisations. J. Effic. Responsib. Educ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, R. Antecedents of job performance of tourism graduates: Evidence from State University-Graduated Employees in Sri Lanka. J. Tour. Serv. 2019, 10, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Effective leadership in online small businesses: An exploratory case study. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2020, 8, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, K.; Malatek, V.; Szewczyk, M. Management practices in area of human resources and monitoring results as determinants of SME’s success in Poland and the Czech Republic. Bus. Adm. Manag. 2020, 23, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, R.Q.; Usman, A. Impact of reward and recognition on job satisfaction and motivation: An empirical study from Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedvicakova, M.; Kral, M. Performance evaluation framework under the influence of industry 4.0: The case of the Czech manufacturing industry. Bus. Adm. Manag. 2021, 24, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankelová, N.; Joniaková, Z.; Romanová, A.; Remeňová, K. Motivational factors and job satisfaction of employees in agriculture in the context of performance of agricultural companies in Slovakia. Agric. Econ. Czech 2020, 9, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, O.I. Employee motivation and organizational performance. Rev. Appl. Socio Econ. Res. 2013, 5, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, M.Y.; Fan, P.; Nepal, S.; Chang, P.C. Dual-mediation paths linking corporate social responsibility to employee’s job performance: A multilevel approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 612565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.A.; Jun, D.; Hassan, Q.; Zubair, R.A.; Iqbal, T. Employee’s performance affected by the alignment of interest and capacity building. Ind. Text. 2020, 71, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, M.C.; Ford, R. Motivating Your Staff to Provide Outstanding Service; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Androniceanu, A. Motivation of the human resources for a sustainable organizational development. Econ. Ser. Manag. 2011, 14, 425–438. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sellero, M.C.; Sánchez-Sellero, P.; Cruz-González, M.M.; Sánchez-Sellero, F.J. Determinants of job satisfaction in the Spanish wood and paper industries: A comparative study across Spain. Drv. Ind. 2018, 69, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruneda, G. Determinantes y evolución de la motivación de los trabajadores en un contexto de crisis económica. Pap. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 99, 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Casuneanu, C. The Romanian employee motivation system: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Math. Models Methods Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 931–938. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco Sierra, A.; Cobos Flores, M.J.; Fuentes Duarte, B.; Hernández Comi, B.I. Successful Management System by a Metalworking Mexican Company During Covid-19 Situation. Analysis through a New Index (Case Study). Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2020, 8, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, L.; Gasior, M.; Sak-Skowron, M. The impact of a time gap on the process of building a sustainable relationship between employee and customer satisfaction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younies, H.; Al-Tawil, T.N. Hospitality workers’ reward and recognition. Int. J. Law Manag. 2020, 63, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M.Z.M.; Nimran, U.; Prasetya, A. The role of motivation in human resources management: The importance of motivation factors among future business professionals in Libya. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Piñero Charlo, J.C.; Ortega García, P.; Román García, S. Formative potential of the development and assessment of an educational escape room designed to integrate music-mathematical knowledge. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Młodzik, M.; León-Guereño, P.; Adamczewska, K. Male and female motivations for participating in a mass cycling race for amateurs. The Skoda bike challenge case study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratričová, J.; Kirchmayer, Z. Barriers to work motivation of generation Z. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 21, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Joniakova, Z.; Blstakova, J. Age management as contemporary challenge to human resources management in Slovak companies. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafagatova, A.; Van Looy, A. Alignment patterns for process-oriented appraisals and rewards: Using HRM for BPM capability building. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neykov, N.; Krišťáková, S.; Hajdúchová, I.; Sedliačiková, M.; Antov, P.; Giertliová, B. Economic efficiency of forest enterprises—Empirical study based on data envelopment analysis. Forests 2021, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Phan, Q.P.T. Greening human resource management and employee commitment towards the environment: An interaction model. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedliačiková, M.; Stroková, Z.; Drábek, J.; Malá, D. Controlling implementation: What are the benefits and barries for employees of wood processing enterprises? Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Publica Slovaca 2019, 61, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mala, D.; Sedliacikova, M.; Dusak, M.; Kascakova, A.; Musova, Z.; Klementova, J. Green logistics in the context of sustainable development in small and medium enterprises. Drv. Ind. 2017, 68, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharčíková, A.; Mičiak, M. Human capital management in transport enterprises with the acceptance of sustainable development in the Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejfarova, M.; Urbancova, H. Application of the competency-based approach in organisations in the Czech Republic. Bus. Adm. Manag. 2015, 18, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaderna, E.; Pechova, J.; Volfova, H. CSR in corona time. Mark. Sci. Inspir. 2020, 15, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacho, Z.; Stachová, K.; Papula, J.; Papulová, Z.; Kohnová, L. Effective communication in organisations increases their competitiveness. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinichenko, M.V.; Klementyev, D.S.; Rybakova, M.V.; Malyshev, M.A.; Bondaletova, N.F.; Chizhankova, I.V. Improving the efficiency of the negotiation process in the social partnership system. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 7, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, M.C.; Tudor, E.M. State of the art of the Chinese forestry, wood industry and its markets. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadudova, J.; Badida, M.; Badidova, A.; Marková, I.; Tahunova, M.; Hroncova, E. Consumer behavior towards regional eco-labels in Slovakia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresová, M.; Sedliačiková, M.; Štefko, J.; Benčiková, D. Perception of wooden houses in the Slovak Republic. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Publica Slovaca 2019, 61, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluš, H.; Parobek, J.; Dzian, M.; Šimo-Svrček, S.; Krahulcová, M. How companies in the wood supply chain perceive the forest certification. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Publica Slovaca 2019, 61, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottwald, D.; Svadlenka, L.; Lejskova, P.; Pavlisova, H. Human capital as a tool for predicting development of transport and communications sector. Communications 2017, 19, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Siposova, M.; Hlava, T. Uses of augmented reality in tertiary education. Augment. Real. Educ. Settings 2019, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, R.B.M.; Khan, A.; Azam, K. Job stress, performance and emotional intelligence in academia. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hroncová, J. Súčasné problémy učiteľskej profesie na Slovensku (Current problems of the teaching profession in Slovakia). Pedagocická Orientace 1999, 3, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dikovic, M.; Gergoric, R. Teachers’ assessment of active learning in teaching Nature and Society. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraz. 2020, 33, 1265–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamoner, Z.; Teruya, M.D.M.; de Souza, M.A.; Suave, A.M.; Monteiro, P.O. The perception of elementary school teachers and students of pedagogy about the future of the teaching profession. Humanid. Inov. 2021, 8, 356–369. [Google Scholar]

- Šipošová, M. Pedagogické Myslenie Učiteľa Cudzieho Jazyka v Teórii a Praxi (Pedagogical Thinking of a Foreign Language Teacher in Theory and Practice); IRIS: Martin, Slovakia, 2021; pp. 1–183. [Google Scholar]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Majauskiene, D.; Valanciene, D. Does perceived stress and workplace bullying alter employees’ moral decision-making? Gender-related. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2020, 19, 323–342. [Google Scholar]

- Louick, R.; Daley, S.G.; Robinson, K.H. Using an autonomy-oriented learning environment for struggling readers: Variations in teacher sense making and instructional approach. Elem. Sch. J. 2019, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, R. Teacher Stress, Job Performance and Self Efficacy among Women Teachers; Lap Lambert Academic Publishing: Chisinau, Republic of Moldova, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, L.; Peixoto, F.; Gouveia, M.J.; Silva, C.J.; Wosnitza, M. Fostering teachers’ resilience and well-being through professional learning: Effects from a training programme. Aust. Educ. Res. 2019, 46, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieben, M.E.; Pressley, T.A.; Matyas, M.L. Research experiences and online professional development increase teachers’ preparedness and use of effective STEM pedagogy. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2021, 45, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, C.; Thomson, M.M. Large-scale assessment as professional development: Teachers’ motivations, ability beliefs, and values. Teach. Dev. 2019, 23, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheva, T.; Antov, P. Application of content and language integrated learning (CLIL) in engineering education. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 63, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Vnouckova, L.; Urbancova, H.; Smolova, H.; Smejkalova, J. Students’ evaluation of education quality in human resource management area: Case of private Czech university. J. Effic. Responsib. Educ. Sci. 2016, 9, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C. Teachers’ professional selves and motivation for continuous professional learning amid education reforms. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 47, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.; Murray, N. An investigation of EAP teachers’ views and experiences of e-learning technology. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossel, K.; Eickelmann, B.; van Ophuysen, S.; Bos, W. Why teachers cooperate: An expectancy-value model of teacher cooperation. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 34, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krišťák, L.; Němec, M.; Danihelová, Z. Interactive methods of teaching physics at Technical Universities. Inform. Educ. 2014, 13, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanic, V.; Urosevic, S.; Dobrosavljevic, A.; Kokeza, G.; Radivojevic, N. Multi-criteria ranking of organizational factors affecting the learning quality outcomes in elementary education in Serbia. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurka, L.V.; Tina, S.; Iztok, R. New challenges in education and schooling: An example of designing innovative motor learning environments. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraz. 2020, 33, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.S.; Li, X.W.; Zou, Y.M. The formation of teachers’ intrinsic motivation in professional development. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 53, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Kang, M.O.; Park, B.J. Factors influencing choosing teaching as a career: South Korean preservice teachers. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnacchiaro, P.; Camminatiello, I.; D’ambra, L.; Palma, R. How does public service motivation affect teacher self-reported performance in an education system? Evidence from an empirical analysis in Italy. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 2521–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, S.; Bardach, L.; Oczlon, S.; Lüftenegger, M. Enhancing feasibility when measuring teachers’ motivation: A brief scale for teachers’ achievement goal orientations. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 83, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Němec, M.; Krišťák, Ľ.; Hockicko, P.; Danihelová, Z.; Velmovská, K. Application of innovative P&E method at technical universities in Slovakia. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 2329–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massry-Herzallah, A.; Arar, K. Gender, school leadership and teachers’ motivations: The key role of culture, gender and motivation in the Arab education system. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2019, 33, 1395–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajasom, A.; Ahmad, Z.A. Principals’ leadership style and school climate: Teachers’ perspectives from Malaysia. Int. J. Leadersh. Public Serv. 2011, 7, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriani, S.; Kesumawati, N.; Kristiawan, M. The influence of the transformational leadership and work motivation on teachers performance. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2018, 7, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Barni, D.; Danioni, F.; Benevene, P. Teachers’ self-efficacy: The role of personal values and motivations for teaching. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartinah, S.; Suharso, P.; Umam, R.; Syazali, M.; Lestari, B.D.; Roslina, R.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Teacher’s performance management: The role of principal’s leadership, work environment and motivation in Tegal City, Indonesia. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Madi, F.N.; Assal, H.; Shrafat, F.; Zaglat, D. The impact of employee motivation on organizational commitment. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Börü, N. The factors affecting teacher-motivation. Int. J. Instr. 2018, 11, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antov, P.; Pancheva, T.V.; Santas, P. Cooperative learning approach in engineering education. Sci. Eng. Educ. 2017, 2, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hitka, M.; Lorinová, S.; Potkány, M.; Balážová, Ž.; Caha, Z. Differentiated approach to employee motivation in terms of finance. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Kozubíková, L.; Potkány, M. Education and gender-based differences in employee motivation. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2018, 19, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vaus, D. Analyzing Social Science Data: 50 Key Problems in Data Analysis; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.G. Beyond ANOVA: Basics of Applied Statistics; Chapman & Hall: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; Available online: https://www.uvm.edu/~dhowell/gradstat/psych341/lectures/RepeatedMeasures/repeated1.html (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Mason, R.D.; Lind, D.A. Statistical Techniques in Business and Economics, 7th ed.; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald, D.; Lejsková, P.; Švadlenka, L.; Rychnovská, V. Evaluation and management of intellectual capital at Pardubice airport: Case study. Proc. Econ. Fin. 2015, 34, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C. What motivates employees according to over 40 years of motivation surveys. Int. J. Manpow. 1997, 18, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynes, S.L.; Gerhart, B.; Minette, K.A. The importance of pay in employee motivation: Discrepancies between what people say and what they do. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropivšek, J.; Jelačić, D.; Grošelj, P. Motivating employees of Slovenian and Croatian wood-industry companies in times of economic downturn. Drv. Ind. 2011, 62, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk Akar, E. Motivations of Turkish pre-service teachers to choose teaching as a career. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shava, F.; Heystek, J. Managing teaching and learning: Integrating instructional and transformational leadership in South African schools context. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, A.; Chabou Othmani, M.; Ben Said, F. Market segmentation in urban tourism: Exploring the influence of personal factors on tourists’ perception. J. Tour. Serv. 2020, 20, 74–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapková, M.; Martinkovičová, M.; Kaščaková, A. Working Heavier or Being Happier? Case of Slovakia. Statistika 2020, 100, 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, R.; Yount, K.M. Structural accommodations of patriarchy: Women and workplace gender segregation in Qatar. Gend. Work Organ. 2019, 26, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñoz, J.J.; Topa, G. Older workers and affective job satisfaction: Gender invariance in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.A. The mediating role of work atmosphere in the relationship between supervisor cooperation, career growth and job satisfaction. J. Workplace Learn. 2019, 31, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.A. Teacher Resilience in adverse contexts: Issues of professionalism and professional identity. In Resilience in Education; Wosnitza, M., Peixoto, F., Beltman, S., Mansfield, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Year | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||||

| Gender | Men | Count | 8 | 68 | 70 | 25 | 24 | 29 | 224 |

| % within | 3.6% | 30.4% | 31.3% | 11.2% | 10.7% | 12.9% | 100.0% | ||

| % within year | 9.3% | 18.9% | 19.7% | 21.4% | 16.0% | 24.2% | 18.8% | ||

| Women | Count | 78 | 292 | 286 | 92 | 126 | 91 | 965 | |

| % within | 8.1% | 30.3% | 29.6% | 9.5% | 13.1% | 9.4% | 100.0% | ||

| % within year | 90.7% | 81.1% | 80.3% | 78.6% | 84.0% | 75.8% | 81.2% | ||

| Total | Count | 86 | 360 | 356 | 117 | 150 | 120 | 1189 | |

| % within | 7.2% | 30.3% | 29.9% | 9.8% | 12.6% | 10.1% | 100.0% | ||

| % within year | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

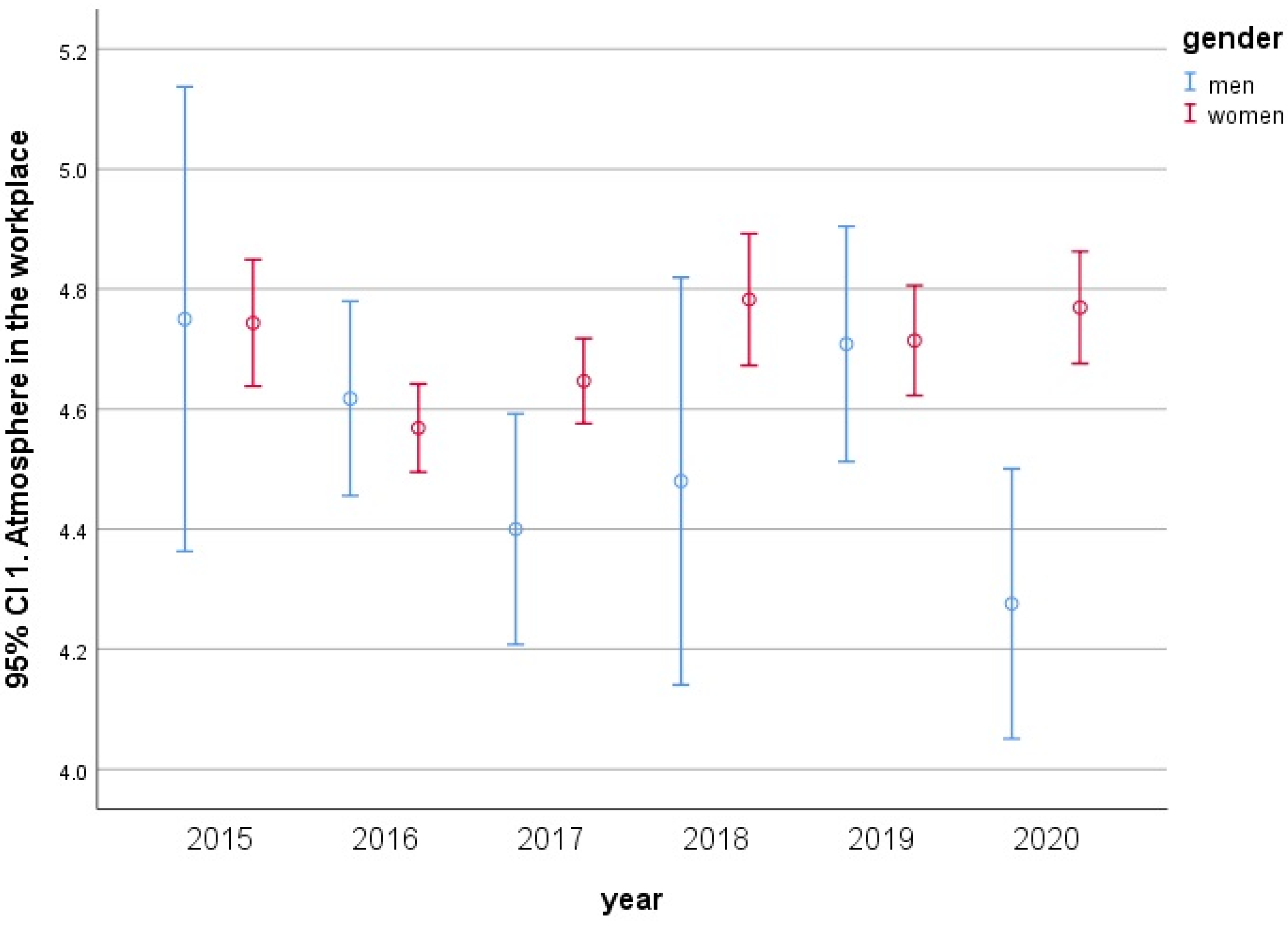

| Motivation factors relating to mutual relationships | 1. Atmosphere in the workplace |

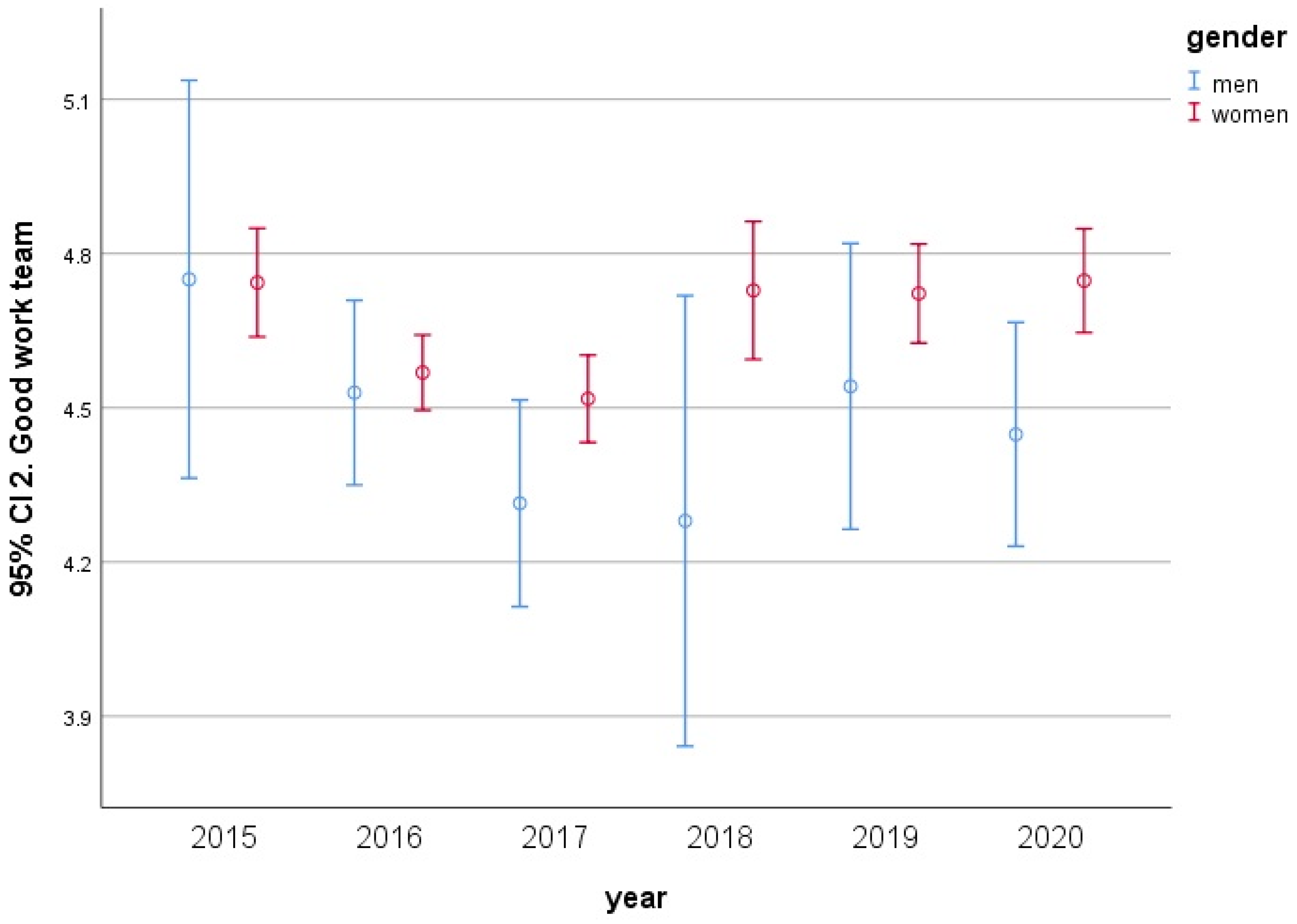

| 2. Good work team | |

| 6. Communication in the workplace | |

| 17. Supervisor’s approach | |

| Motivation factors relating to career aspiration | 8. Opportunity to apply one’s own ability |

| 14. Career advancement | |

| 15. Competences | |

| 16. Prestige | |

| 18. Individual decision making | |

| 19. Self-actualization | |

| 26. Personal growth | |

| 29. Recognition | |

| Motivation factors relating to finance | 3. Fringe benefits |

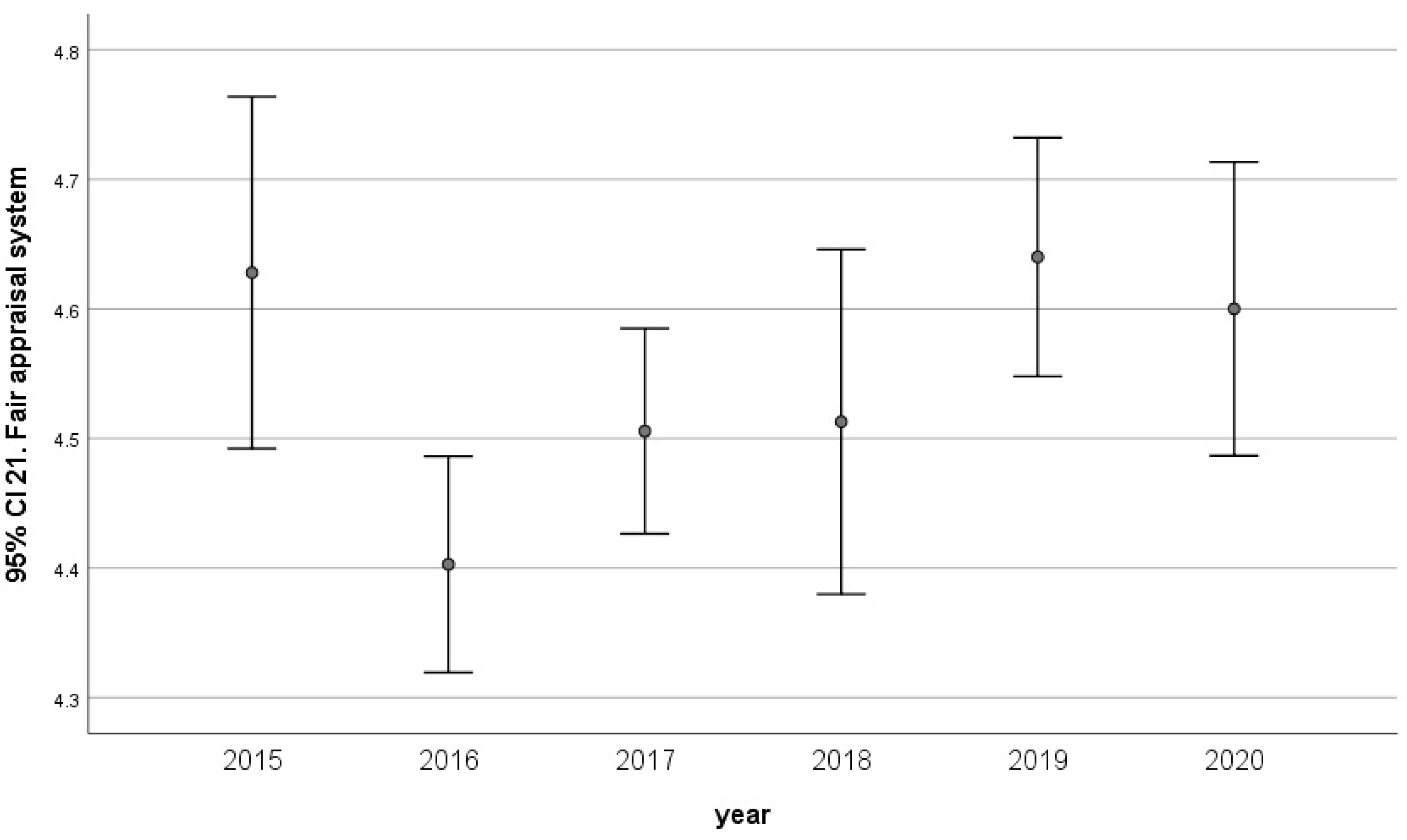

| 21. Fair appraisal system | |

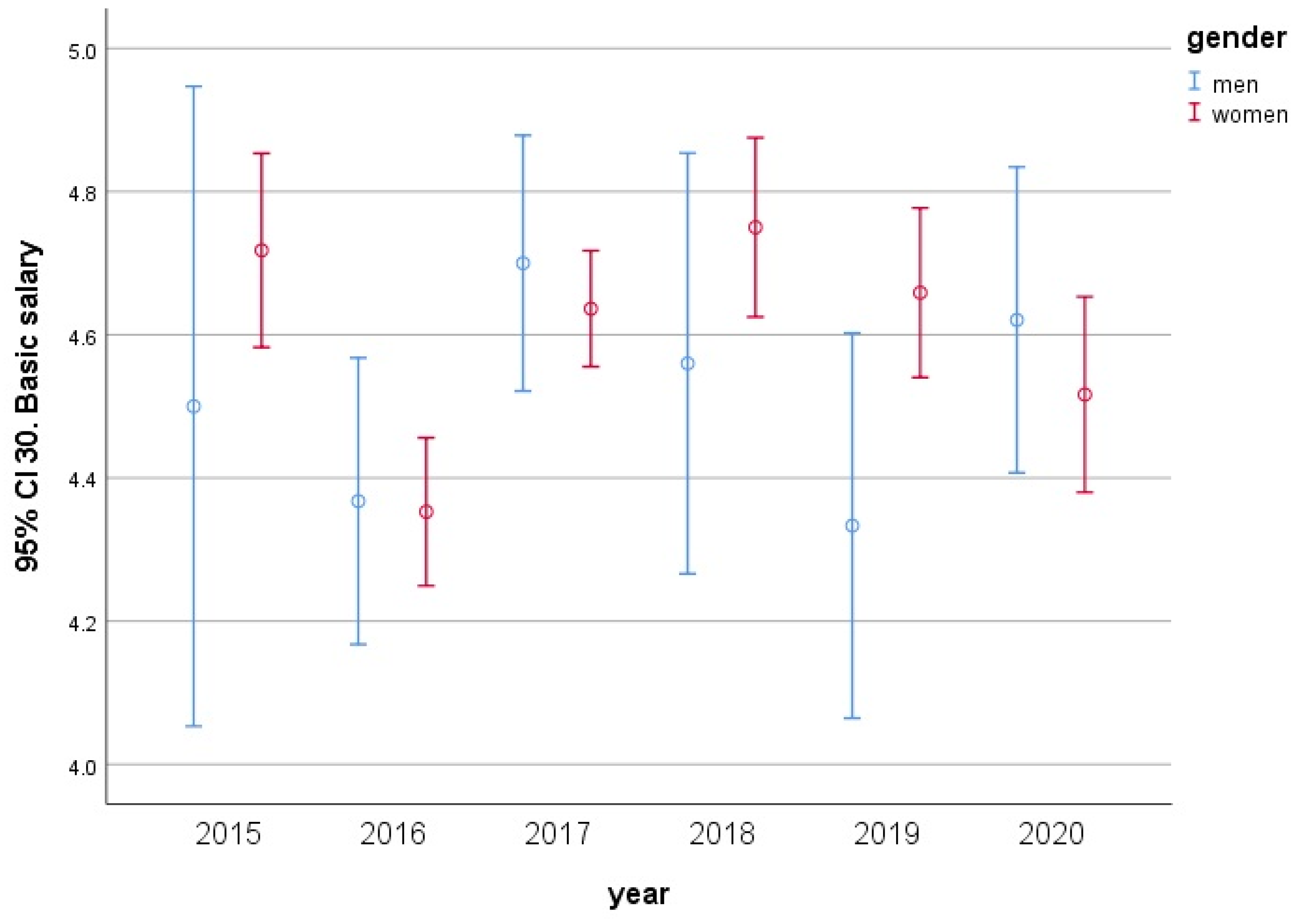

| 30. Base salary | |

| Motivation factors relating to work conditions | 4. Physical effort at work |

| 5. Job security | |

| 9. Workload and type of work | |

| 10. Information about performance result | |

| 11. Working hours | |

| 12. Work environment | |

| 13. Job performance | |

| 22. Stress | |

| 23. Mental effort | |

| Motivation factors relating to social needs | 7. Name of the educational organization |

| 20. Social benefits | |

| 24. Mission of the educational organization | |

| 25. Region’s development | |

| 27. Relation to the environment | |

| 28. Free time |

| Motivational Factor | Scale Mean If Item Deleted | Scale Variance If Item Deleted | Corrected Item Total Correlation | Squared Multiple Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere in the workplace | 18.16 | 4.028 | 0.512 | 0.337 | 0.644 |

| Good work team | 18.21 | 3.977 | 0.457 | 0.312 | 0.662 |

| Supervisor’s approach | 18.28 | 3.769 | 0.477 | 0.229 | 0.653 |

| Fair appraisal system | 18.28 | 3.808 | 0.457 | 0.226 | 0.662 |

| Basic salary | 18.24 | 3.821 | 0.430 | 0.203 | 0.675 |

| Motivational Factor | Mean | Confidence Interval −95% | Confidence Interval 95% | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere in the workplace | 4.64 | 4.60 | 4.67 | 0.602 |

| Good work team | 4.59 | 4.55 | 4.63 | 0.670 |

| Base salary | 4.56 | 4.52 | 4.60 | 0.745 |

| Fair appraisal system | 4.51 | 4.47 | 4.55 | 0.722 |

| Supervisor’s approach | 4.51 | 4.47 | 4.55 | 0.730 |

| Job security | 4.48 | 4.44 | 4.52 | 0.751 |

| Communication in the workplace | 4.47 | 4.43 | 4.51 | 0.709 |

| Fringe benefits | 4.43 | 4.39 | 4.47 | 0.739 |

| Work environment | 4.34 | 4.30 | 4.38 | 0.757 |

| Working hours | 4.32 | 4.27 | 4.36 | 0.778 |

| Recognition | 4.29 | 4.25 | 4.34 | 0.820 |

| Stress | 4.26 | 4.21 | 4.31 | 0.905 |

| Workload and type of work | 4.24 | 4.20 | 4.29 | 0.772 |

| Social benefits | 4.24 | 4.19 | 4.29 | 0.843 |

| Opportunity to apply one’s own ability | 4.24 | 4.19 | 4.28 | 0.812 |

| Job performance | 4.24 | 4.19 | 4.28 | 0.792 |

| Self-actualization | 4.24 | 4.19 | 4.28 | 0.801 |

| Mental effort | 4.17 | 4.12 | 4.22 | 0.925 |

| Personal growth | 4.17 | 4.12 | 4.22 | 0.849 |

| Information about performance result | 4.15 | 4.10 | 4.20 | 0.848 |

| Free time | 4.13 | 4.08 | 4.18 | 0.916 |

| Individual decision-making | 4.11 | 4.06 | 4.16 | 0.858 |

| Career advancement | 4.07 | 4.02 | 4.12 | 0.870 |

| Mission of the educational organization | 3.99 | 3.94 | 4.04 | 0.906 |

| Relation to the environment | 3.98 | 3.92 | 4.03 | 0.954 |

| Name of the educational organization | 3.95 | 3.90 | 4.01 | 1.007 |

| Competences | 3.94 | 3.89 | 3.99 | 0.938 |

| Region’s development | 3.83 | 3.78 | 3.88 | 0.964 |

| Prestige | 3.83 | 3.77 | 3.88 | 0.987 |

| Physical effort at work | 3.75 | 3.70 | 3.80 | 0.968 |

| Motivation Factor | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

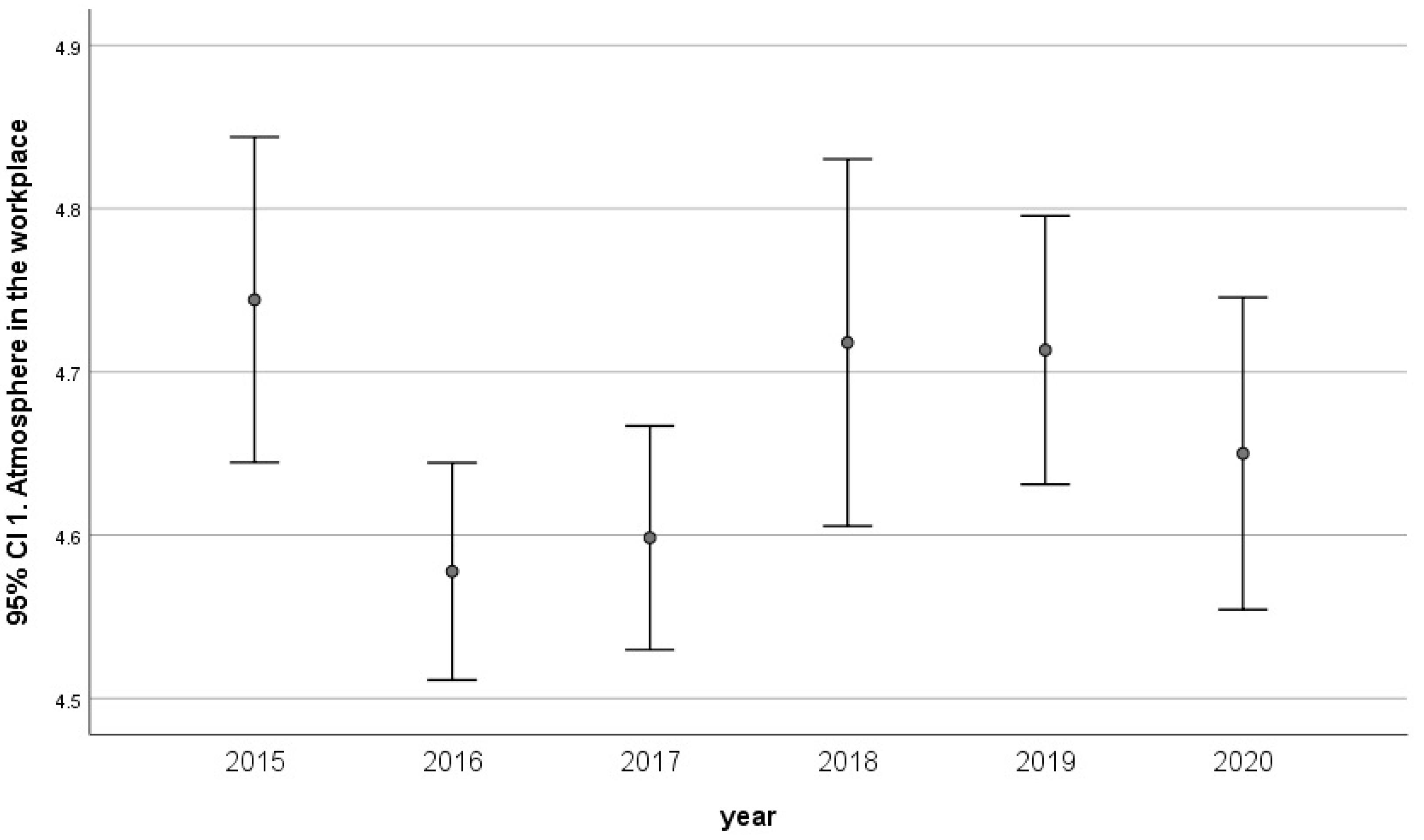

| 1. Atmosphere in the workplace | Between groups | 4.435 | 5 | 0.887 | 2.410 | 0.035 |

| Within groups | 435.419 | 1183 | 0.368 | |||

| Total | 439.854 | 1188 | ||||

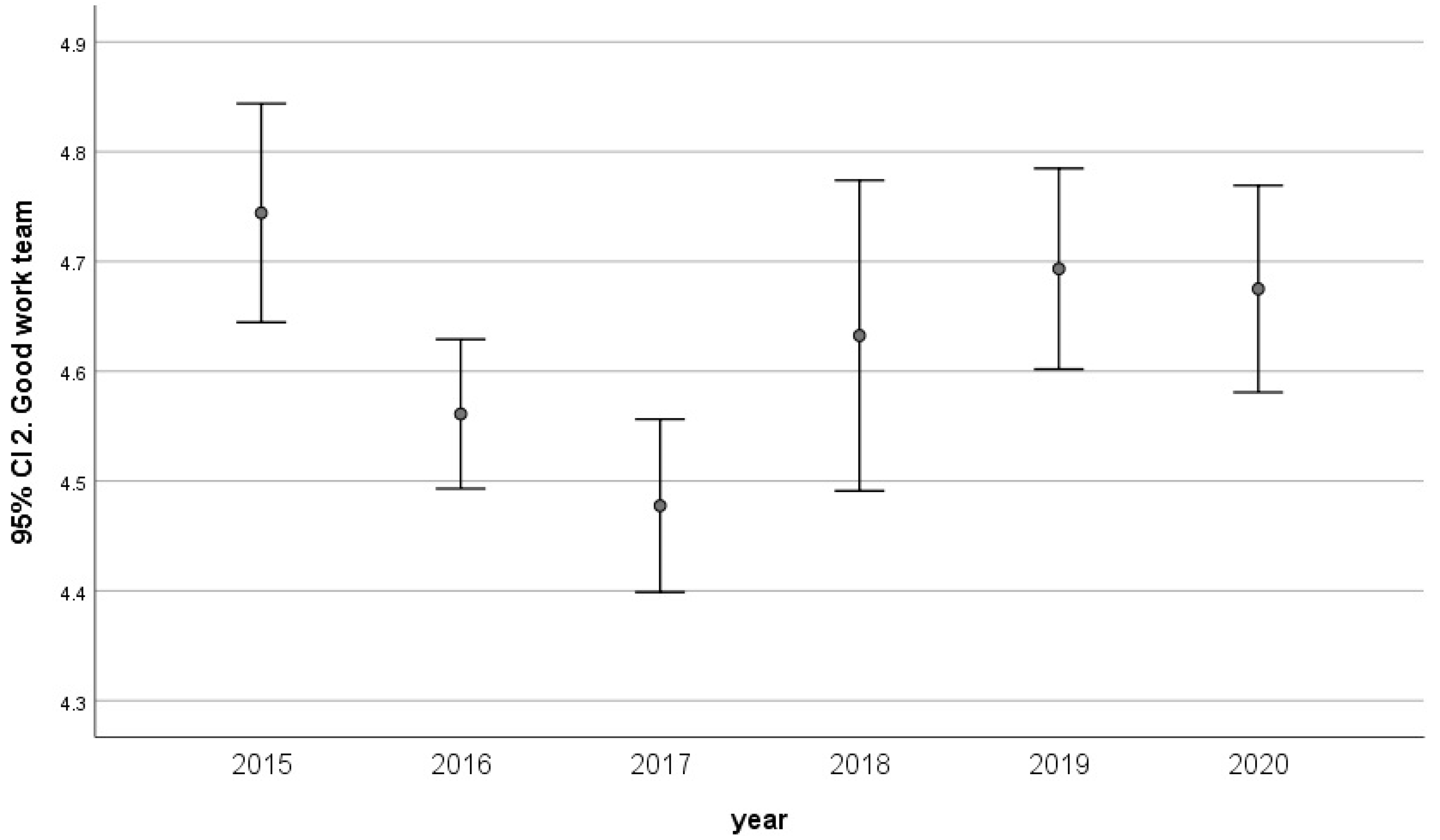

| 2. Good work team | Between groups | 9.492 | 5 | 1.898 | 4.276 | 0.001 |

| Within groups | 525.263 | 1183 | 0.444 | |||

| Total | 534.755 | 1188 | ||||

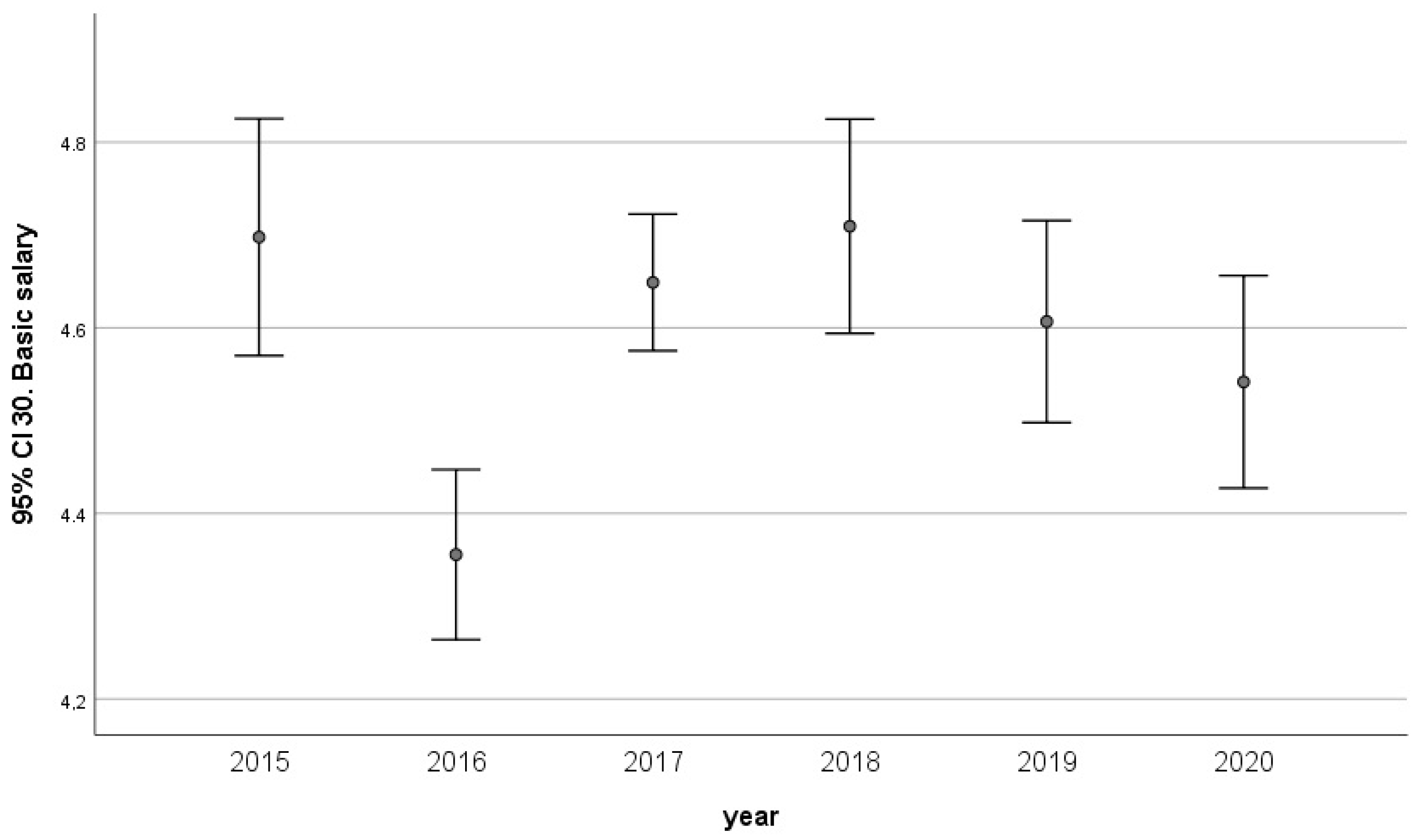

| 30. Basic salary | Between groups | 22.416 | 5 | 4.483 | 8.166 | 0.000 |

| Within groups | 649.443 | 1183 | 0.549 | |||

| Total | 671.859 | 1188 | ||||

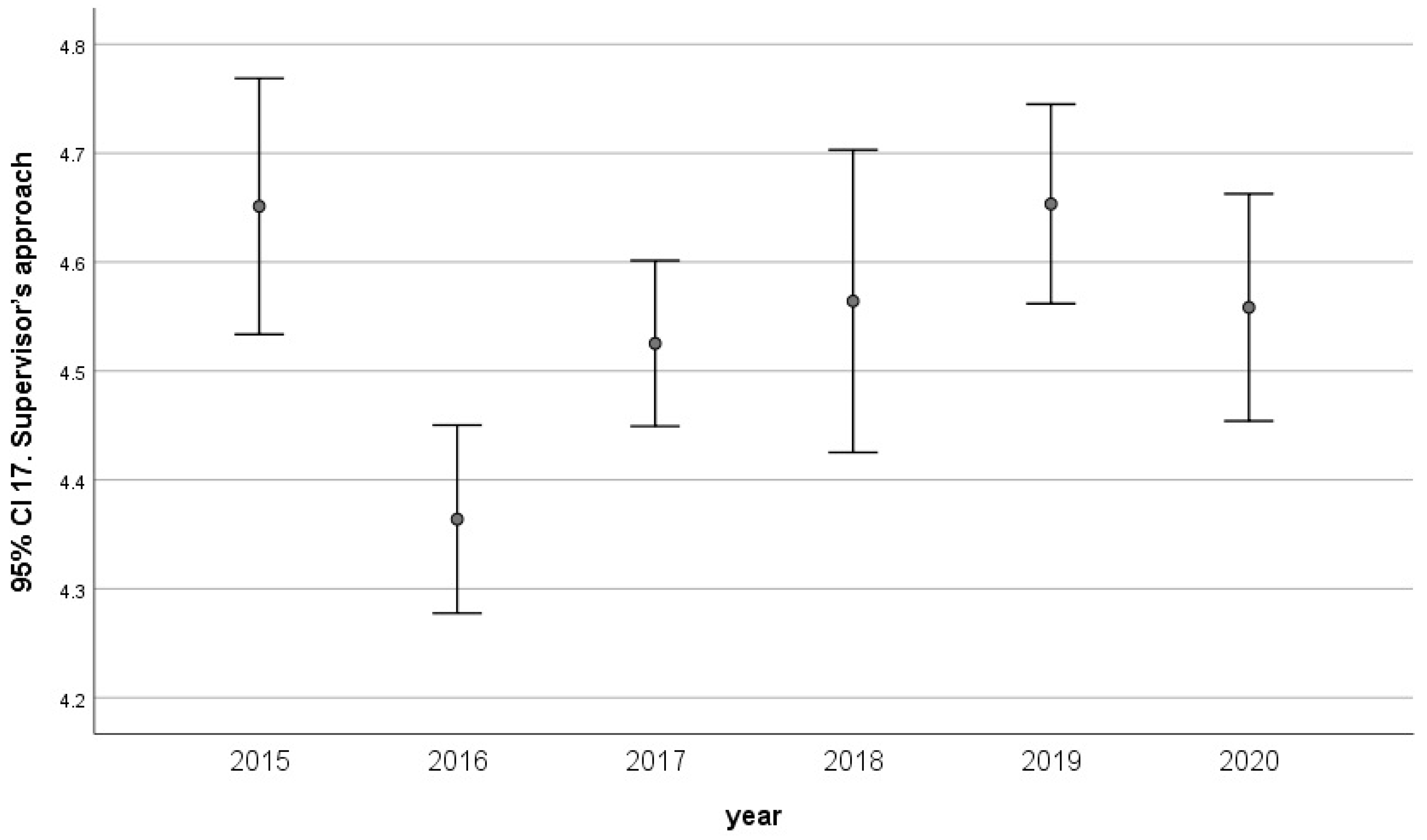

| 17. Supervisor’s approach | Between groups | 13.185 | 5 | 2.637 | 5.048 | 0.000 |

| Within groups | 617.972 | 1183 | 0.522 | |||

| Total | 631.157 | 1188 | ||||

| 21. Fair appraisal system | Between groups | 8.849 | 5 | 1.770 | 3.332 | 0.005 |

| Within groups | 628.270 | 1183 | 0.531 | |||

| Total | 637.119 | 1188 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Javorčíková, J.; Vanderková, K.; Ližbetinová, L.; Lorincová, S.; Hitka, M. Teaching Performance of Slovak Primary School Teachers: Top Motivation Factors. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070313

Javorčíková J, Vanderková K, Ližbetinová L, Lorincová S, Hitka M. Teaching Performance of Slovak Primary School Teachers: Top Motivation Factors. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(7):313. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070313

Chicago/Turabian StyleJavorčíková, Jana, Katarína Vanderková, Lenka Ližbetinová, Silvia Lorincová, and Miloš Hitka. 2021. "Teaching Performance of Slovak Primary School Teachers: Top Motivation Factors" Education Sciences 11, no. 7: 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070313

APA StyleJavorčíková, J., Vanderková, K., Ližbetinová, L., Lorincová, S., & Hitka, M. (2021). Teaching Performance of Slovak Primary School Teachers: Top Motivation Factors. Education Sciences, 11(7), 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070313