Abstract

Ireland’s system of special education has undergone unprecedented change over the last three decades. Following major policy developments in the mid-2000s which emphasised inclusive education, there have been changes to special education school personnel and funding structures which seek to include greater numbers of students with disabilities in mainstream education. There is one anomaly however: Ireland continues to operate a parallel system of special schools and classes with an emphasis on special class provision for students with disabilities. The aim of this paper is to examine the evolution of Ireland’s special education policy over the past three decades and explore the extent to which it is compatible with its obligations under the United Nations Convention for People with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and more recent discussions around moving to inclusive education. It uses a systematic investigation of policy and administrative data on special class growth over time to highlight anomalies between the policy narrative around inclusive education in Ireland and the continued use of segregated settings. The current system, therefore, suggests confused thinking at a policy level which has resulted in the implementation of special education grafted on to the general education system. Any move to an inclusive system therefore, in order to be successful, would require a root and branch overhaul of existing policies.

1. Introduction

The Republic of Ireland, in common with many European countries, developed a parallel system of special and general education over the 20th century. The earliest responses to the learning needs of children and young people who have disabilities and/or additional learning needs were confined to isolated initiatives developed by voluntary and religious organisations, with very limited input from the State. From the 1960s onwards, State involvement in educational provision for these young people increased with the funding of category specific special schools and special classes in regular schools. As a result, special educational provision existed on the periphery of the general education system, often with separate funding mechanisms, curricula, and assessment.

2. A Change in Policy Emphasis 1990s

From the 1990s onwards, there was a discernible shift in emphasis in government policy from a focus on educational provision for specific categories of disabled children towards a more inclusive approach to educating children with learning needs and/or disabilities within mainstream schools. This policy shift was influenced by a combination of international and national developments. Internationally, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) became a significant driver for policy change in educational provision for children with additional learning needs and/or disabilities. Parallel developments within the European Union increased the momentum to re-examine existing educational provision. There was strong evidence from Canada and the United States that more inclusive approaches could be established and reinforced by legislative provision and significant investment in teacher education. In the Republic of Ireland, there were significant changes in special educational provision during the 1990s through a combination of government sponsored reviews of the existing provision and parental litigation that highlighted serious shortcomings within current educational provision for their children. The Special Education Review Committee (SERC) established by the Department of Education and Science in 1991 which reported in 1993 documented serious shortcomings in special educational provision [1]. Shortcomings included the lack of educational supports for individual children and their families; inadequate curricular provision; lack of therapeutic supports; limited specialist training for teachers. Not surprisingly, the Committee recommended that significant resourcing was required to address these shortcomings. The SERC Report marked a significant departure for the State in recognising its’ responsibility for the education of children with learning needs and/or disabilities and a move away from a system that was overly dependent on charity and goodwill. Parental litigation was initiated against the State on behalf of children who had Autism and/or severe/profound intellectual disabilities. Specific cases such as O’Donoghue v. Minister for Health (1993) and Sinnott v. Minster for Education (2001) strongly argued that these children had been systematically ignored by the State and that current educational provision was seriously inadequate. As a result of this litigation the State was obliged to recognise that these children had the right to receive an appropriate education based primarily on their learning needs rather than their medical needs which had traditionally been the case.

3. Legislation in the Late 1990s and 2000s

From the 1990s the State has initiated policy developments that have resulted in enabling legislation, an emerging support infrastructure, and significantly increased funding. Parallel systems of special and mainstream education have often been underpinned by legislation reflecting the traditional emphasis on health dominated concerns when addressing the educational needs of children and young people who have disabilities and/or additional learning needs. The Education Act (1998) which provides the statutory basis for policy and practice relating to all educational provision marked a departure from this traditional approach within an Irish context [2]. There is an explicit recognition within the Act that children and young people with disabilities and/or additional learning needs should access educational provision on an equal basis to their non-disabled peers. For example, each reference to children and young people availing of educational provision is followed by the phrase ‘including those who have a disability or who have other additional learning needs.’ In common with many other jurisdictions, anti-discrimination legislation accelerated changes in policy and provision. The Equal Status Act (2000) prohibited discrimination on nine grounds, including disability. Schools are subject to the provisions of this Act and are required to provide appropriate accommodations to enable these children and young people to participate in school programmes [3].

The Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs (EPSEN) Act (2004) marked another significant milestone in establishing sustainable educational provision for this population [4]. Educational inclusion represents a core value in this Act and it is recognised that education for these children and young people should take place in an inclusive environment alongside their non-disabled peers. Exclusion from mainstream provision should be the exception rather than the norm in addressing the educational and social needs of this cohort. Unfortunately, critical aspects of this legislation, including mandatory individual education plans, remain to be implemented as the State refused to progress these provisions citing the economic recession. The definition of disability and/or Special Educational Needs (SEN) in the EPSEN Act (2004) marked a significant divergence from the traditionally deficit dominated definitions. The EPSEN definition encompassed a wide range of difficulties experienced by children and young people to include physical, sensory, mental health or learning disabilities or ‘any other condition which results in a person learning differently from a person without that condition’. The Act also established the National Council for Special Education to take responsibility for special needs provision within schools and co-ordinating services throughout the country. It was anticipated that this more devolved structure involving locally based Special Education Needs Organisers (SENOs) would respond more effectively and flexibly to local needs throughout the country.

4. Funding and Resource Allocation

Providing adequate special needs provision was a major priority for the Department of Education and Science who introduced the General Allocation Model for primary schools in 2005. This resourcing model was intended to address the learning needs of students with high incidence additional learning needs including those who have milder levels of learning difficulties and would usually be eligible for learning support. Students deemed to have low incidence additional learning needs (complex and enduring needs) continued to be allocated resource hours based on a psychological assessment combined with a SENO evaluation. This attempt to lessen dependence on assessments to secure provision, while laudable, was only partially successful. Parents were often forced to pay for assessments to secure appropriate provision for their children and sometimes schools had the unenviable task of deciding which children would qualify for the state sponsored assessments [5]. Serious doubts about the reliability and validity of the SEN/disability categories were raised that undermined the existing resource allocation system [6]. SEN prevalence rates established by Author (2011), at 25 per cent, aligning with many international studies, challenged the adequacy of existing provision [7].

From 2011 to 2019 increased government expenditure for special needs provision was very evident, despite the impact of the economic recession. This additional funding was allocated to three key initiatives: (i) additional teaching posts (increased by 46%), (ii) Special Needs Assistants posts (increased by 51%), (iii) provision of special classes (increased by 196%) [8]. Despite these significant funding increases challenges persisted in achieving a more inclusive school system. Research studies highlighted serious problems in accessing timely assessments, the appropriateness of the existing linkage between assessment and provision, ‘soft’ barriers to enrolment of children with SEN in their local schools, inadequate therapeutic supports in mainstream schools, concerns about creating over dependency with individualised Special Needs Assistant (SNA) support, transition difficulties and limited professional education opportunities for general education teachers [5,9,10,11,12,13,14].

The Department of Education and Skills (DES) and NCSE have made a concerted effort to address these difficulties in recent years, though, it is too soon to judge whether the Government sponsored initiatives will have the desired impact in creating an inclusive school system. Major initiatives include the establishment of the School Inclusion Model (SIM) and the introduction of a demonstration project involving specialised therapeutic support from speech and language and occupational therapists. Other changes include the introduction of the Education (Admission to Schools) Act, 2018 which sought to address ‘soft’ barriers to school enrolment and the introduction of learning programmes at levels 1 and 2 on the National Framework of Qualifications by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment to provide appropriate certification for young people who have additional learning needs [15].

Despite many advances in support provision and the emergence of a national support infrastructure persistent difficulties remain. The rapid expansion of the special class model to facilitate provision for students with additional needs in mainstream schools is a case in point. To date, there has been very limited investigation of the efficacy of this model apart from Author et al. (2014) and Author et al. (2016) and little indication that concerns raised about this model in these studies have been addressed [9,12]. The special class model as it operates internationally and nationally is now examined and the implications for the continued expansion of this model within an Irish context discussed.

5. The Persistence of Special Classes Internationally

In light of the UNCRPD, special schools and classes have, perhaps, become the crux of the inclusion debate. Inclusive education research highlights the continued use, and expansion, of special classes and segregated settings more generally which is at odds with the prevailing policy narrative. This divide between inclusive education policy and practice on the ground is highlighted by Ebersold (2011) who argues that having an ‘education for all’ policy does not necessarily mean that all children are educated together in mainstream classes [16]. This research shows that 18 of the 23 countries in the study were operating some form of special class provision for students with additional needs. In one Austrian study [17] the authors describe how more than a third of all students who have been diagnosed with a disability are educated in segregated settings known as ‘integration classes’ [17] (p. 91). Similarly, in Finland, where special schools are in the decline, 23 per cent of students are in ‘part-time special education’ (1:1 or small groups) with another 7.3 per cent in ‘special support’ or special education classes in mainstream schools [18].

Despite the continued use of segregated settings, there is little evidence that students in these classes benefit from such placements. Research in this area is complex due to the level of variation that exists across different national contexts in the language and terminology used to describe resource rooms (Greece) or special units, integration classes (Australia), least restrictive environment (LRE) and functional grouping (United States), special education classrooms (Finland) and learning support units (England) [17,18,19,20,21]. In some countries, placement in special classes is full-time but temporary or used as an early intervention. Other countries have more permanent settings where children attend the class for just part of the school day. The language also varies around whether special classes are considered an inclusive practice in a school or whether they act as forms of segregation [22,23] or separation of children [21].

In addition to issues around language, research evaluating special classes has been impacted by methodological problems such as small sample sizes or, because from an ethical viewpoint, students placed in these classes are a difficult to access group. Measures of academic progress are also complicated by the extent to which countries vary in whether students in special classes are included in international standardised tests such as PISA or TIMMS. One exception however is a Norwegian study [23] which looked at the attainment of students in special classes but also asked whether special class placement was beneficial for them overall. The findings indicate little difference in the attainment of students in these classes compared to their peers in mainstream and stress the benefits of mainstream schools with additionally resourced provision over and above full-time placement in special classes.

One review of studies found that students with disabilities in mainstream classes are more likely to achieve better academic results and qualifications compared to those in special class settings and therefore impact on their chances of gaining access to employment or entering further or higher education when they leave school [16]. This review also notes the important social capital gained in mainstream classes for these students which facilitates access to employment and adult life more generally. It shows that young people with disabilities who are educated in mainstream classes gain important social skills useful in their professional and social life after school [16].

Other studies however argue that these specialised settings can offer unique advantages, including small class sizes, specially trained teachers, emphasis on functional skills and individualised instruction [24,25]. By removing these classes, some commentators believe they are removing the opportunity for these students to undertake more vocationally oriented curricula and work placements thus limiting their ability to gain employment and become members of their community when they leave school [25].

Special Classes in Ireland

Although special classes have been in existence in Ireland since the mid-1970s, it was not until the late 2000s that their numbers began to grow and their designation changed from settings primarily intended for students with Mild General Learning Difficulties to classes for students with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD). The NCSE and DES are primarily responsible for the provision and designation of special classes and describe their role as being ‘part of a continuum of educational provision that enables students with more complex additional learning needs to be educated, in smaller class groups, within their local mainstream schools’ [26]. A parallel system of provision has thus been created where special units or classes are attached to mainstream primary and secondary schools with many designated for students with Autism. Schools wishing to establish a special class have to have a minimum number of children seeking a class placement in the school in order to make an application. The NCSE also takes the level of special class provision in a local area into account. Students in special classes are supposed to have a diagnosis of a disability and a written professional recommendation for placement in this kind of setting. These settings have a reduced student-teacher ratio compared with the mainstream classes and are allocated SNAs depending on their designation. Special classes with an Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) designation have a student–teacher ratio of 6:1 with two SNAs per class whereas classes for students with Mild General Learning Disabilities (MGLD) have a ratio of 11:1 [9].

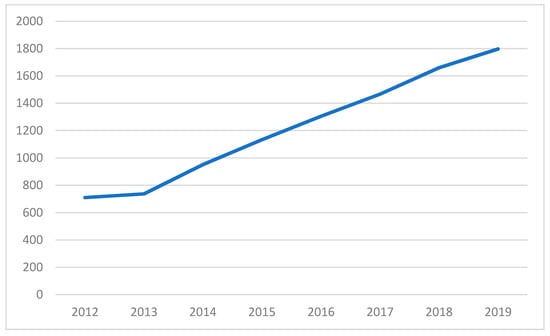

Special classes have now become an established feature of special education in Ireland due mainly to their increase in numbers over the last decade. Between 2001 and 2009 the number of special classes was in decline in Ireland, however since 2009–2010 they have increased with between 100 and 200 classes opening each year. By 2014 the numbers of these classes had reached the level of provision in 2000 of just under 1000 classes [27]. Figure 1 graphs the growth in this form of provision over time with just over 700 classes in operation in the academic year 2012–2013 compared to almost 1800 in the year 2019–2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Growth of special classes 2012–2019 [27].

The increase in provision has drawn much attention across government with recent spending reviews [28,29] calling for cost control. These reviews note the special class cost per student increased by 11 per cent between 2012 and 2019 and given the 80 per cent increase in student numbers, this has led to overall increases of 145.5 per cent. Mirroring the increased student numbers, special class teacher numbers have also increased by 136.4 per cent during this period with much of the costs related to teacher pay [29] (p. 10).

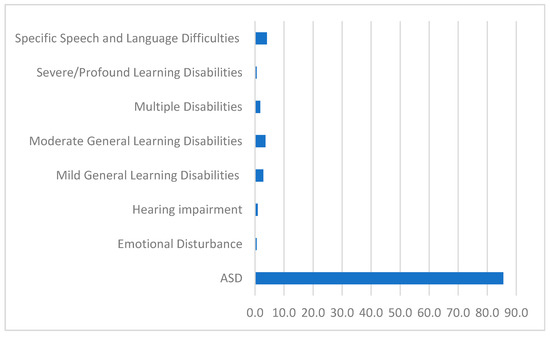

Perhaps the most notable feature of Irish special classes over the last decade is their designation being primarily for students with Autism. Where special classes are sanctioned, the NCSE and the SENO are responsible for setting them up and assigning them a designation based on the level of demand [19]. Over 85 per cent of special classes in Ireland are now designated for students with ASD with the second largest designation categories being classes for students with Specific Speech and Language Difficulties (SSLD) and classes for students with an MGLD diagnosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Designation of special classes in Ireland, 2020 [27].

The growth in the prevalence of students with Autism is the subject of much debate internationally [30,31,32]. In the Republic of Ireland, there is limited data available with the most recent prevalence estimate of school-aged children at 1.5 per cent [33] whereas in Northern Ireland this rate is higher at 4.2 per cent [34]. Despite the relatively low prevalence rates for students with Autism compared to other disabilities in the Republic, there is little discussion on why they are the primary focus of special education provision in Ireland at present. Parents and advocacy groups for students with Autism have gained much media attention in recent years in their attempts to get children places in special classes in their local schools, particularly where schools have been resistant [35,36]. While parents are simply demanding that their child’s educational needs are met in their local school, a recent evaluation of ASD classes by the DES Inspectorate (2020) cautioned that the level of demand by Irish media and parental advocacy groups for the opening of new ASD classes brings with it ‘a danger that segregated educational provision could expand unintentionally’ [36].

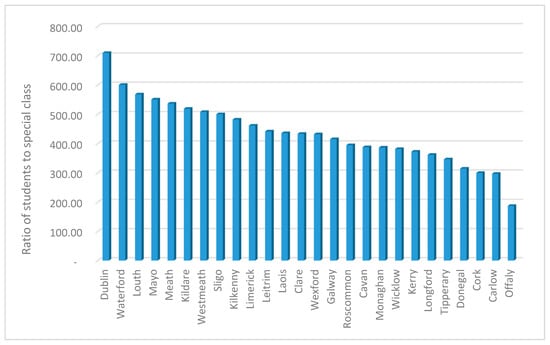

Given the way in which special classes are established, their distribution across Ireland often depends on levels of demand. The NCSE publishes annual special class figures on its website by county, designation and education sector (early intervention, primary and secondary level). By analysing this data relative to the school age population by each county in Ireland it is possible to measure the distribution of special classes and explore whether these classes are meeting levels of ‘need’. Figure 3 shows that there is large variability in how special classes are distributed with the ratio of student to special classes highest in county Dublin where there is the largest school aged population (special class to student ratio of 1:700). In contrast, county Offaly special class provision is relatively high with special class to student ratio of 1:187. These patterns suggest a lack of planning at government level about special class provision which accounts for population structures and the prevalence of disabilities/additional needs.

Figure 3.

Special class to student ratio by county [27,38].

Although national figures are helpful in understanding special class provision, there is a clear need to understand the experiences of students in these classes, their access to the national curriculum, the structure of their school day and their progression and outcomes when they leave the special class setting. One national longitudinal study of special class provision [9,12] explored many of these aspects of special class provision and found much variability in how special classes were operationalised in mainstream schools. Despite special classes being perceived as an intervention or temporary placement, it found that placement in special classes is often permanent with some students remaining in these settings for the entire day and throughout their school career. The report highlights the difficulties of this at the secondary level where many special classes are assigned one teacher to cover the full curriculum [12]. A more recent evaluation of special classes at primary and secondary level by the Department of Education and Skills (DES) Inspectorate found that some students placed in special class settings can remain there with little integration with mainstream classes. It highlights the need to take account of Ireland’s obligations under the UNCRPD:

“if full inclusion or ultimate enrolment into mainstream classes is to be viewed as the index of success, the current system of special classes appears to be having limited success for many learners who enrol in a special class”[37] (p. 7).

The report acknowledges that integration is taking place between some special and mainstream classes but stresses the need to ‘extend this integration further towards full inclusion’ [37].

Placement in special classes can also be particularly problematic at secondary-level education where research shows students can experience stigma and lowered expectations by their teachers. Author et al. (2014) note that for students with more severe disabilities, these settings offered the opportunity to attend mainstream education instead of a special school, albeit in a separate setting [9]. The report highlights however that in some instances, students are being placed in special classes when there is no need for them to be there. They found that in some instances, secondary level students with mild needs and, in some cases, those with no diagnosis of disability, are placed in such classes. The DES Inspectorate evaluation (2020) also found that some students at the secondary level are being placed in special class settings where ‘they are capable of greater integration with the mainstream classes’ [37].

The research also highlights issues around teacher placement in special classes and the need for qualifications and experience in order to effectively teach in such settings. Author et al. (2016) found that teachers working in special classes were often younger, newly recruited staff or those covering maternity leave periods and on temporary contracts [9]. The findings show that where teachers lacked specific qualifications in special education and/or support from their colleagues and school leaders there was a risk of teacher stress and in some cases burnout. The study also highlighted the role of effective inclusive school leadership in how teachers are placed in such settings and can access appropriate continuous professional development when requested. Similarly, the DES Inspectorate (2020) recommendations also stress the importance of school leadership in deciding which teachers are allocated to special classes and states that ‘newly qualified or substitute teachers should not be deployed to the special class’ [37] (p. 8).

Given increases in the numbers of special classes and, in particular, the number of special class teachers and SNAs required to staff this model of provision, there has been increased focus on the level of spending for special education in recent years [39,40,41]. Mirroring the increased prevalence of students with disabilities/additional learning needs in mainstream education, special education budgets have increased by over 52 per cent between 2011 and 2019 [29,41]. In an attempt to curb spending and introduce a more equitable system of resource allocation, the NCSE introduced a new funding model which signalled a departure from traditional funding models explicitly linking provision with individual student assessments towards a model based on the profiled need of each school. The NCSE policy advice (2014) clearly stated that: ‘… the current model for allocating the 10,000 additional learning support and resource teacher posts to schools was inequitable at best and potentially confirmed social advantage and reinforced social disadvantage’ [42] (p. 3). Introduced in 2018, the new model comprises two key components: School educational profile based on (i) Students with complex needs, (ii) Percentages of students performing below a certain threshold on standardised test results, (iii) Social context of school which includes gender, primary school location and educational disadvantage; and a baseline allocation designed: ‘…to ensure that every school is an inclusive school and able to enrol and support students who may have additional needs’ [42] (pp. 7–8). The move away from an assessment dominated mode of resource allocation has been facilitated by the development of the Continuum of Support model [43] that is designed to provide a tiered model of support both within and outside schools.

There has been no evaluation of this model to date but is considered to be a significant departure from the traditional linkage between resource allocation and professional assessments.

More recently however, debates around inclusive education have escalated in Ireland. The NCSE Progress report (2019) titled ‘An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society?’ poses fundamental questions regarding how Ireland can establish inclusive school environments [8]. This review of existing provision and future plans has been prompted by the Irish government’s ratification of the UNCRPD in 2018 [44]. Article 24 (2) of the CRPD: ‘obliges States, inter alia, to ensure that children can access an inclusive, quality and free education on an equal basis with others in the communities in which they live’ [8] (p. 3). The UN Committee that monitors implementation of the Convention has already advised that having a separate special education system operating in parallel with a mainstream education system is not compatible with the provisions of the CRPD. In response to the State ratification of the CRPD and the significant changes in policy and provision over the past decade, the NCSE decided to review whether: ‘special schools and classes should continue to be offered as part of the continuum of educational provision for students with more complex additional learning needs or whether greater inclusion in mainstream classes offers a better way forward’ [8] (p. 4).

This progress report documents conflicting views among stakeholders regarding whether special schools and special classes should be retained. Proponents of special school/class provision argue that it is economically efficient and facilitates the delivery of specialist teaching and therapeutic inputs. Opponents of this model of provision point to what they consider to be serious shortcomings including: once placed in a special setting, there is little likelihood that the student will move from this setting for the whole of their school careers; students often have to travel long distances to access the special school often losing the connection with their local community; many special school buildings are seriously deficient and ill-suited to educational and therapeutic supports; and high levels of challenging behaviour among students has been reported. Based on evidence gathered from research studies and extensive consultation with stakeholders the report authors conclude that significant progress has been made in establishing a more equitable resourcing system and that many mainstream schools have demonstrated a commitment to developing inclusive learning environments. Despite this progress there remain, as outlined above, significant difficulties with the current system of special education provision.

In the gathering of evidence for this progress report, NCSE personnel visited New Brunswick, Canada to assess their full inclusion model. This small province is internationally understood to have implemented an inclusive system of education through legislation and best practices [45]. In New Brunswick, the term ‘inclusion’ is used to refer to all students including socially disadvantaged, First Nation, newcomers, those with a disability or additional learning need and those with exceptional ability. Full inclusion is viewed ‘as a fundamental human right principle underpinning the education system’ [8] (p. 51). Overall, NCSE gave a very positive evaluation of the full inclusion model and observed that schools were very committed to the task of full inclusion as demonstrated by strong leadership, teacher confidence in including all students, parental support and a pro-active approach to addressing any issues that arise.

6. Discussion

Ireland appears to be at a crossroads in relation to facing the challenge of establishing inclusive school environments. The Irish government commitment to adhering to the provisions of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities appears to have prompted a radical rethink by policymakers. Over the past two decades, Ireland has developed an extensive system of supports for students who have additional needs across mainstream and special settings. However, Ireland now faces the fundamental question about whether it wishes to reconfigure the supports and focus on how inclusive learning environments can be established as envisaged in the EPSEN Act (2004).

The ‘New Brunswick’ model of inclusion is being seriously considered by policymakers for the first time and this has prompted a review of existing provision and challenged the traditional mindset that promoted special schools and special settings within mainstream schools for students with additional needs. This paper argues that the retention of special schools and special settings is based on a number of assumptions that have rarely been challenged to produce compelling evidence to justify their existence. It is assumed that special schools and special settings are better resourced and capable of delivering better quality academic and social outcomes for their students. This perhaps helps to explain why the greater preponderance of students in special schools are of secondary-level school age and many have transferred into special schools having completed their primary school education. However, both internationally and nationally there is very little evidence that attendance at special schools produces greater academic and social outcomes for their students [46]. Parents and care givers are naturally reluctant to be seen to abandon special settings given their struggle to achieve appropriate educational provision for their children in the first place. This is understandable but sometimes based on a lack of information about the supports readily available to their children within mainstream settings.

Administrative convenience is another possible reason for the persistence of segregated settings as there is somewhere for children with additional needs to be placed and stave off the understandable anger and frustration of families faced with securing appropriate educational provision for their children. The current thinking appears to be to provide the physical space, a unit or special class within mainstream schools, a support teacher and special needs assistants and see what happens instead of providing funding or resources to schools, not only for student supports but for building teacher capacity which encourages inclusive practice. It can be argued that systems of segregation remain in place due to a lethargic approach by the government to institute real reform and face the challenges of establishing mainstream pathways for every child. History and legacy remain the key influence on Ireland’s current systems of teacher education, special education funding, pedagogical approaches and curriculum. Ireland has undergone a considerable transformation in a relatively short time regarding the establishment of legislative and administrative structures designed to support students with special educational needs in mainstream schools. Simultaneously, special schools have remained in existence and extensive special class provision has been established in mainstream schools. While we have limited evidence to support the effectiveness of these types of provision, it is very clear that these forms of provision retain considerable support among education stakeholders. While the ‘New Brunswick’ total inclusion model is being actively considered, it is unlikely that a major overhaul of current provision will take place in the immediate future despite the pressures exerted by signing up to the provisions of the UNCRPD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.S.; Data Curation: J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data on special classes are from the NCSE website ‘Special Classes in Primary and Post Primary Schools Academic Year 20/21’ https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/List-of-Special-Classes-September-2020.15.09.2020-1.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021). Data on Department of Education statistics are from the central Statistics office website https://www.cso.ie/en/databases/departmentofeducation/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Government of Ireland. Special Education Review Committee (SERC); The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. The Education Act; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. The Equal Status Act; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs (EPSEN) Act; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R.; Shevlin, M.; Winter, E.; O’Raw, P. Project IRIS–Inclusive Research in Irish Schools A Longitudinal Study of the Experiences of and Outcomes for Pupils with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Irish Schools; NCSE: Trim, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Desforges, M.; Lindsay, G. Procedures Used to Diagnose a Disability and to Assess Special Educational Needs: An International Review; NCSE: Trim, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S. A Study on the Prevalence of Special Educational Needs; NCSE: Trim, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Special Education. Policy Advice on Special Schools and Classes. An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society? Progress Report; NCSE: Trim, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S.; Frawley, D.; Kingston, G.; Shevlin, M.; Smyth, F. Special Classes in Irish Schools Phase 2: A Qualitative Study; NCSE: Trim, Ireland; ESRI: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, S.; O’Connor, U. The shifting role of the special needs assistant in Irish classrooms: A time for change? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2012, 27, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerins, P.; Casserly, A.M.; Deacy, E.; Harvey, D.; McDonagh, D.; Tiernan, B. The professional development needs of special needs assistants in Irish post-primary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 33, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S.; Frawley, D.; Watson, D.; Shevlin, M.; Smyth, F. Understanding Special Class Provision in Ireland; NCSE: Trim, Ireland; ESRI: Dublin, Ireland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Guckin, C.; Shevlin, M.; Bell, S.; Devecchi, C. Moving to Further and Higher Education: An Exploration of the Experiences of Students with Special Educational Needs. Research Report Number 14; NCSE: Trim, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, G.; Kamp, A.; Cochrane, A. Transition (s) to work: The experiences of people with disabilities in Ireland. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 1556–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ireland. The Education (Admission to Schools) Act; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ebersold, S. Inclusive Education for Young Disabled People in Europe: Trends, Issues and Challenges, A synthesis of Evidence from ANED Country Reports and Additional Sources; National Higher Institute for Training and Research on Special Needs Education, INSHEA: Suresnes, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner, T.; Proyer, M.D. From special to inclusive education policies in Austria—Developments and implications for schools and teacher education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 43, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloviita, T. Attitudes of Teachers towards Inclusive Education in Finland. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 64, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, V.; Didaskalou, E.; Argyrakouli, E. Preferences of students with general learning difficulties for different service delivery modes. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2006, 21, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. Education That Fits: Review of International Trends in the Education of Students with Special Educational Needs; Ministry of Education: Christchurch, South Island, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McLeskey, J.; Landers, E.; Williamson, P.; Hoppey, D. Are We Moving Toward Educating Students with Disabilities in Less Restrictive Settings? J. Spec. Educ. 2010, 46, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markussen, E. Special education: Does it help? A study of special education in Norwegian upper secondary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2004, 19, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myklebust, J.O. Class placement and competence attainment among students with special educational needs. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2006, 33, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J.; Hallahan, D.P. Toward a Comprehensive Delivery System; Charles, E., Ed.; Merrill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, J.; Hornby, G. Inclusive Vision versus Special Education Reality. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council for Special Education. Guidelines for Setting Up and Organising Special Classes; NCSE: Trim, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Special Education. Special Classes in Primary and Post Primary Schools Academic Year 20/21. Available online: https://ncse.ie/special-classes (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- DPER. Spending Review 2017 Special Educational Needs provision; Department of Public Expenditure and Reform: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DPER. Spending Review 2019 Monitoring Inputs, Outputs and Outcomes in Special Education Needs Provision; Department of Public Expenditure and Reform and Department of Education: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne, E. Editorial: The rising prevalence of autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baio, J.; Wiggins, L.; Christensen, D.L.; Maenner, M.J.; Daniels, J.; Warren, Z.; Kurzius-Spencer, M.; Zahorodny, W.; Robinson Rosenberg, C.; White, T.; et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014, MMWR. Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, L.; Imran, N.; Nazeer, A.; Skokauskas, N.; Waqar Azeem, M. Autism spectrum disorder. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 127, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boilson, A.M.; Staines, A.; Ramirez, A.; Posada, M.; Sweeney, M.R. Operationalisation of the European Protocol for Autism Prevalence (EPAP) for Autism Spectrum Disorder Prevalence Measurement in Ireland. J. Autism Dev. Dis. 2016, 46, 3054–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, H.; McCluney, J. Prevalence of Autism (including Asperger Syndrome) in School Age Children in Northern Ireland Annual Report; Department of Health: Belfast, Northern Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, K. Minister in Schools Stand-Off over Additional Special Classes. Irish Independent. 11 July 2019. Available online: https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/education/minister-in-schools-stand-off-over-additional-special-classes-38301862.html (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- O’Brien, C. More South Dublin Primary Schools Agree to Open Classes for Special Needs Pupils. Irish Times. 3 December 2020. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/more-south-dublin-primary-schools-agree-to-open-classes-for-special-needs-pupils-1.4426972 (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- DES Inspectorate. Educational Provision for Learners with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Special Classes Attached to Mainstream Schools in Ireland; Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistics Office. Department of Education, Education Statistics. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/databases/departmentofeducation/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Banks, J. A Winning Formula? Funding Inclusive Education in Ireland. In Resourcing Inclusive Education (International Perspectives on Inclusive Education, Vol. 15); Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. Examining the Cost of Special Education. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Sharma, U., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; Frawley, D.; McCoy, S. Achieving inclusion? Effective resourcing of students with special educational needs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council for Special Education. Delivery for Students with Special Educational Needs; NCSE: Trim, Ireland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Skills. Special Educational Needs: A Continuum of Support; DES: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 24th ed.; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- AuCoin, A.; Porter, G.P.; Baker-Korotkov, K. New Brunswick’s journey to inclusive education. Prospects 2020, 49, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddington, E.M.; Reed, P.; Baker-Korotkov, K. Comparison of the effects of mainstream and special school on National Curriculum outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder: An archive-based analysis. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2016, 17, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).