Abstract

This article reports the Swedish results and experiences from the survey study “Educators’ perspectives of belonging in early years education,” which was part of the research project “Politics of belonging: Promoting children’s inclusion in educational settings across borders”. The purpose of the survey study was to gain knowledge about the preschool staff’s perspective on factors and pedagogical approaches that promote diversity and belonging. The research questions and study instruments were co-produced by researchers from Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Netherlands and Sweden. This Swedish part reports the answers from 180 respondents/staff from preschools. The experiences and the way the results are analysed and discussed are entirely from the investigation conducted in Sweden. The results show that the staff’s work environment, values and working methods are important for an inclusive programme. Preschool children are a source of strength for building a sense of belonging for all children, and increased confidence in their ability provides better conditions for creating an inclusive preschool; that is, giving children more influence and trust promotes the sense of belonging. In addition to these results, the survey has provided important methodological experience and initiated a discussion on how the contact between academia and preschool programmes can be improved.

1. Introduction

An inclusive and cohesive preschool and school, where students with different backgrounds and abilities meet, are important to maintain if we want to safeguard a democratic society. Educating and learning together are crucial to later being able to live and work together []. Given values based on social justice and the equal right to participation, there is the principle that all people, regardless of their conditions, interests and performance capabilities, participate in a community. This means seeing the importance of the group’s differences and individualising within the framework of the community. Differences become assets and not problems []. In order for all citizens to feel a sense of belonging, it is therefore important to work inclusively early in the school system.

Concepts often associated with adaptation are “included” and “inclusion”. “Included” as a goal stands for all children, regardless of differences, being equally involved in the same activity. “Inclusion” as a method describes a process where special efforts are deemed necessary so that every individual’s differences will be accepted [].

Another concept besides “included” that can describe how well all children are encompassed by the programme is a “sense of belonging.” The meaning of the term “belonging” can be explained by a slight re-wording of the definition formed by Emanuelsson []: When the absence from a group or of a group member feels like a minus, as something negative, then a two-way sense of belonging has developed. A sense of belonging is essential for children in a preschool programme. The feeling, in its essence, must be mutual between a group and an individual, and a permissive, attentive atmosphere is important. The same conditions also apply to staff and parents if a positive environment is to be achieved. It is important to map out how this work takes place, and which factors and methods promote and hinder the inclusion process. With this background, the purpose of the present study was formulated.

2. Purpose

The purpose of the survey is to gain knowledge about the preschool staff’s perspective on factors and pedagogical approaches that promote diversity and belonging.

Definitions of Key Concepts for the Study

The definitions formulated for the study and presented to the respondents in an online survey’s cover letter were as follows. “Belonging refer to processes of inclusion and exclusion among children and educators in their everyday preschool practice. Belonging is connected with diversity in a broad sense. The term groups of diverse children (and/or diversity) refer to children with different social or/and cultural backgrounds, religions, values, languages, gender, (dis)abilities, or needs. This means that all children are diverse in some way. Participation can be an expression of belonging (being involved in a community, a place, activities and practices) and it can vary according to degree of involvement experienced by educators and children. The term inclusion refers both to political decision-making and interactions within the (pre)school community. At the policy level, inclusion refers to taking care and educating children with diverse backgrounds and needs. At the interactional level, inclusion refers to forming groups and joint activities within the community. Cultural sensitivity refers to a receptivity towards and understanding of the cultural backgrounds of children.”

3. Previous Research

The following sections, which deal with previous research on inclusive factors in preschool and school, are presented based on a two-part model with the categorisation based on the concepts “inner and outer inclusion capital” []. The inner inclusion capital refers to the factors that are linked to the individual teacher’s competence, such as knowledge and ability to organise groups and activities. The outer inclusion capital includes factors that surround the teacher, for example, the environment, technology, staff resources, cooperation and management.

3.1. Inner Inclusion Capital

Previous studies have shown that staff attitude is of great importance for the success of an inclusive programme [,]. A teacher’s empathetic attitude increases the children’s ability to respect and understand other people [,], and a teacher who is committed and positive is more successful in this work []. It is important that preschool staff discuss and take a position on which view of the child/pupil and knowledge will form the basis for pedagogical efforts []. That pedagogical documentation can support teachers in their professional development and make them aware of their own competence has been confirmed in surveys outside Sweden []. The feeling of belonging in a context is also primary for inclusion to be working [], and therefore collaboration among colleagues should be encouraged []. Everyone in the work team possesses competence, and by reflecting together, different problems can be illuminated from different viewpoints. This way, educators gain a deeper understanding of different situations and of what measures should be taken, which in turn can contribute toward developing a more inclusive group of children [].

The teacher’s education and knowledge are very important for children’s development and learning [,,]. Skills regarding an inclusive approach come from the teacher education, which is unfortunately often inadequate []. Teachers therefore demand more continuing education and support to be able to work inclusively, which is a request noted in several studies [,,,]. If teacher education provides teachers with the tools and confidence to see opportunities with inclusion, this leads to positive attitudes towards inclusion []. The importance of staff as role models should not be underestimated, and it is therefore important that work with children with special needs is highly valued by management and other colleagues.

Previous studies have shown that teachers are generally positive or neutral towards inclusion [,,]. On the other hand, some are negative about working inclusively in their own groups and classes []. There are also studies that report a clear reluctance to include [,].

Participation and belonging are important for self-esteem and strengthening group belonging for all pupils []. For the feeling of belonging to exist, inclusive activities in social contexts are important []. Educators must work diligently toward creating preschool and school environments where the social community is positive and where children feel a sense of belonging in the group [,]. That pupils are actively involved in planning is also emphasised in earlier studies [,]. Previous research shows that children are seldom listened to for their thoughts about learning []. Teachers would go farther in their teaching if pupils gained more influence over their learning and had their unique knowledge heard [].

For each child to feel a sense of belonging, it is essential that each teacher adapts tasks and activities to the conditions of individual children []. It is important to find each pupil’s strengths and then find appropriate pedagogical methods for further progress. Through this approach, children’s self-esteem is strengthened, and mutual perceptions and attitudes towards other individuals can be positively influenced []. Educators who are sensitive to children’s interests can identify interesting areas of knowledge for all children []. It is a qualified task, of course, for educators to get children to participate in joint activities, as at the same time, the pupils must be challenged based on their individual abilities and needs [].

3.2. Outer Inclusion Capital

Obstacles to or opportunities for participation can be created depending on how the physical environment is designed []. An environment with loud noise can drastically lower the ability to learn for some children []. An environment basically characterised by continuity and structure is often emphasised when working with special needs pupils []. Children often have very limited opportunity to influence the environment, and it is important to increase their influence on this point [].

Resources are important, but they do not automatically lead to inclusion [,]. It is common for teachers to demand more resources to be able to work inclusively [], but according to several researchers, resources are less important for successful inclusion compared to teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion [,]. Discussions about lack of resources often lead to focusing on the children’s difficulties instead of the visions and strategies of the programme []. Technology and pedagogical material are also emphasised as important for creating an inclusive environment, particularly possibilities with digital learning tools. It is important that these are not considered special aids, which may then be perceived as negatively stamping the user []. Technology is noted as having future potential for children needing special support [].

Good contact with children’s parents, especially the guardians of children and pupils assessed to have special needs, is of great importance for shaping an inclusive programme. Communication and information working well in both directions facilitates inclusion []. When parents in an atmosphere of respect become involved in the preschool’s activities, the opportunities for an inclusive activity increase [].

It is very important that national and local policy documents state inclusion as an overarching principle for pedagogical efforts []. Virtanen’s [] study has shown that preschool teachers have much knowledge and respect for the preschool curriculum. With this awareness, many preschool teachers may feel frustration over the discrepancy between what is stated in the school law and curriculum and what happens in the preschool [,]. It is clear that the preschool is approaching the school’s culture when it comes to documentation and assessment practice [,]. It becomes very clear that documentation has a strong focus on the individual child where a traditional, school-oriented learning is highly valued [,,].

4. Methods

4.1. Data Collection Instruments

The survey questions were constructed in 2019 in collaboration with preschool researchers from Finland, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. The questions were discussed based on the preschool programmes of the different countries and were formulated jointly in English. Then, the items were translated into the languages of each participating country.

In addition to background information such as age, years of service and education, the survey contained 70 questions. Of these, 56 were multiple-choice questions, ten questions ranked alternatives and three were open-ended questions. The multiple-choice questions were constructed as statements in which the respondent would disagree or agree on a seven-point scale.

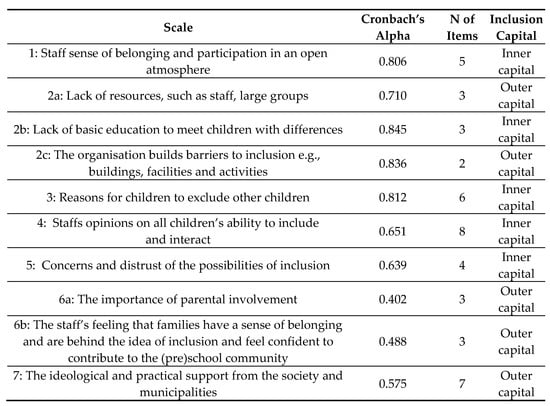

After the questions were constructed, a factor analysis was performed, revealing ten question areas/factors with relatively high correlation. Factor analysis attempts to bring inter-correlated variables together under more general, underlying variables. More specifically, the goal of factor analysis is to reduce the dimensionality of the original space and to give an interpretation to the new space, spanned by a reduced number of new dimensions which are supposed to underlie the old ones. Factor analysis offers the possibility of gaining a clear view of the data. Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of internal consistency, that is, how closely related a set of items are as a group. It is considered to be a measure of scale reliability. As the average inter-item correlation increases, Cronbach’s alpha increases as well. The general rule of thumb is that a Cronbach’s alpha of 70 and above is good. This means that five factors reached this limit, while two factors were close and two with a greater distance []. The factors and their weights are presented in the table below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The ten question areas/factors represented in the survey.

4.2. Context and Participants

The data collection in Sweden was carried out using a web survey distributed via the personal e-mail addresses of preschool staff. The aim was to cover an area where the location of preschools varied geographically and socio-demographically. The Swedish data collection was carried out in two regions with six municipalities participating. To guarantee the demographic spread, the surveys were distributed proportionally among large cities, smaller communities and rural areas.

After contacting and receiving approval from the education administrators of the participating municipalities, emails were sent to the principals who chose to offer their staff participation in the investigation. The principals then forwarded information about the study and the link to the online survey to the staff’s personal email addresses. In one municipality, the responsible researcher sent the study information and questionnaires directly to the staff from e-mail lists received from the central administration.

The Swedish part of the project has been approved by the national ethics review authority, with special attention to required openness, self-determination for participants, confidential treatment of the research material and autonomy regarding use of the research material []. Participation in the survey was completely voluntary, and the answers were anonymous and untraceable to any municipality or specific preschool. A total of 1641 surveys were distributed. After two weeks, a reminder was sent out to all prospective participants, and the opportunity to respond expired after four weeks.

4.3. Response Rate and Distribution

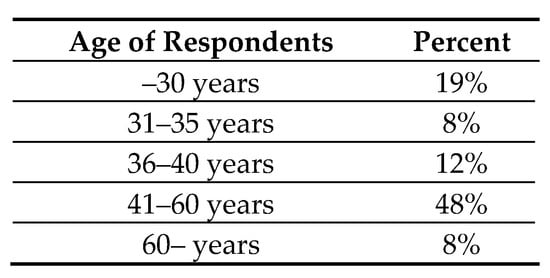

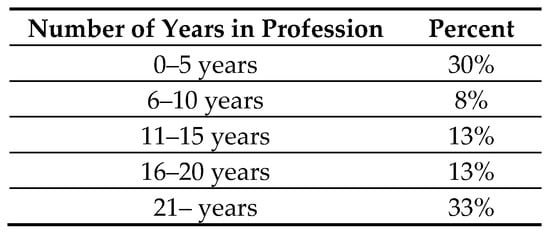

The response rate was very low, which will be reviewed in the next section and in the methods discussion. There are 180 people, which is 11%, where 88% of these are women, 3% men and 9% did not state the gender. The majority, 48%, of those who responded, are between 41 and 60 years old (Figure 2). Nearly one-third, 30%, have worked for less than five years, and staff who have worked for more than 21 years account for another third (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Age of respondents.

Figure 3.

Number of years in profession.

Ninety percent of the staff have been educated for working in a preschool. Of these, 56% are preschool teachers and 26% childcare workers. This leaves 8% who state they have another education involving preschool, and 10% of the respondents lack education or have been educated for other work.

4.4. Dropout

It is not possible to perform a valid dropout analysis, as the dropout cannot be traced to individual municipalities, preschools or employees. A significant part of the dropout is probably due to the principals not distributing the survey to their staff. Other reasons for the low response rate are “survey fatigue” of the preschool programme and uncertainty surrounding the new data law (GDPR) recently introduced in the EU. The scope of the survey, the formulation and construction of the questions also do not favour a high response rate. There is probably an over-representation of staff in the dropout group who are neutral, negative or uninterested in inclusion issues in comparison with those who responded to the survey. As each questionnaire contains information about the respondent’s education, gender, age and years in the profession, the 180 responses obtained, despite the dropout, are valuable data for discussions about important factors in creating and maintaining an inclusive environment. The results do not report the internal dropout, as it was very low; no question had a greater dropout rate than eight individuals.

5. Results

5.1. Scale 1: Staff Sense of Belonging and Participation in an Open Atmosphere

The absolute majority (93%) of the staff who participated in the survey feel a sense of belonging in the preschool activities and can discuss issues of ‘inclusion’ and be listened to in a constructive atmosphere. Respondents concur that colleagues share this sense of belonging (71%) but are unsure whether everyone is comfortable discussing issues related to inclusion, as more than one-third (40%) feel hesitant about this. Close to one-quarter (21%) responded with neutral answers, indicating that one cannot really assess other staff’s experiences of openness and belonging (Table 1).

Table 1.

Staff sense of belonging and participation.

5.2. Scale 2a: Lack of Resources, Such as Staff, Large Groups

Approximately three-quarters of the respondents consider the groups of children to be too large (73%) and that there is a lack of resources and staff to respond to an “inclusion” activity (72%). Few people believe that group size (18%), resources (14%) and staff allocation (19%) are satisfactory (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lack of resources.

5.3. Scale 2b: Lack of Basic Education to Meet Children with Differences

Nearly half of the respondents (44%) state that they have not had any further education about children with special needs. More than one-third (38%) believe they lack the skills and knowledge to meet this group, and almost one-quarter (21%) express their uncertainty by giving a neutral answer to this question (Table 3).

Table 3.

Lack of basic education.

5.4. Scale 2c: The Organisation Builds Barriers to Inclusion e.g., Buildings, Facilities and Activities

One-quarter (25%) of the respondents think that the group interaction is hindered by barriers in the buildings, physical environments and programme. This has consequences for the individual child’s sense of belonging. More than half of the respondents oppose the statement that the premises and other physical conditions form obstacles to the possibility of an inclusive interaction (58%) and the children’s opportunity to feel they belong (53%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Barriers to inclusion.

5.5. Scale 3: Reasons for Children to Exclude Other Children

Staff assess that children at the preschool have a permissive approach to their peers. A small percentage of staff, less than 10%, believe that other children act negatively toward individual children due to their minority language 9%, social status 6%, disability 4%, cultural background 3%, other causes 3%, and religion 1%. Ten comments were provided for “other causes,” namely, age, shyness, outgoing behaviour, gender patterns and poor self-confidence. About one-quarter (27%) gave a neutral answer to the question of whether language can be a factor that causes children to exclude other children (Table 5).

Table 5.

Reasons for children to exclude.

5.6. Scale 4: Staffs Opinions on All Children’s Ability to Include and Interact

The majority of staff believe that preschool children are capable of communicating in a way that includes other children (76%) and that they on their own can create a situation that includes children with special needs (56%).

On the statements that were negatively formulated, 30% consider that the children do not have the ability to take responsibility for including other children, and 27% consider that the children could not create peer relationships without staff help. A further 29% state that children cannot take the perspective of children with special needs, and 37% believe that children cannot stand up for other children’s rights. Thirty percent believe that children with special needs would have problems becoming part of the peer community, and 27% believe that children with other languages could have a hinderance to participating in peer interactions (Table 6).

Table 6.

Staffs opinions on all children’s ability to include.

5.7. Scale 5: Concerns and Distrust of the Possibilities of Inclusion

Nearly one-third (28%) believe that they do not have enough competence to support children with diverse abilities and/ or backgrounds. The same response pattern is seen in the number (27%) who believe that children with diverse abilities and/or backgrounds create instability in the group of children. Although many state that they have sufficient skills, many (54%) are concerned about how best to support children with diverse abilities, and even more (74%) are worried that the time for this support is not sufficient (Table 7).

Table 7.

Concerns and distrust.

5.8. Scale 6a: The Importance of Parental Involvement

An absolute majority of the respondents believe that it is important to communicate and discuss with the parent of a child who excludes another child (89%). The same attitude prevails regarding communicating and discussing with the parent of a child who is excluded (87%). On the statement if they include parents in decisions about goals and working toward inclusion, there are fewer (56%) who say they do this (Table 8).

Table 8.

The importance of parental involvement.

5.9. Scale 6b: The Staff’s Feeling that Families Have a Sense of Belonging and Are Behind the Idea of Inclusion and Feel Confident to Contribute to the (Pre)School Community

More than half the staff (62%) believe that all parents have a sense of belonging in the preschool programme. Roughly the same number of staff (57%) think that parents with a different background feel safe to participate in the preschool activities, but almost one-quarter believe that parents with a background other than Swedish do not feel comfortable with the preschool culture. The majority (56%) also consider that the preschool values correspond with those of the parents. Only a few (7%) think the opposite (Table 9).

Table 9.

The staff’s feeling that families have a sense of belonging.

5.10. Scale 7: The Ideological and Practical Support from the Society and Municipalities

When asked if the curriculum supports an inclusive programme, the majority of staff (82%) respond there is clear support. Regarding support from the special needs teacher, almost as many (79%) indicate they receive this help. The majority of the staff believe that there is a positive attitude in Sweden (79%) and that legislation and policy documents facilitate an inclusive programme (73%). Not as many are satisfied with the concrete support to the preschool (51%), and many lack further education for working with children with special needs (37%) (Table 10).

Table 10.

The ideological and practical support.

5.11. 8–9. Please Rank Each of These Goals in Order of Importance for You as an Educator

When staff rank the most important goals in terms of inclusion, they choose the alternatives “that all children are accepted ‘as they are’” and “that all children are included in peer groups” (Table 11). The staff think it is important to develop an understanding of differences in children by discussing their own and others’ emotions related to diversity. Reaching an understanding through learning special facts ranks last (Table 12).

Table 11.

Ranked goals in order of importance for educators.

Table 12.

Ranked specific goals in order of importance.

5.12. 10–11. Please Select One of the Following Pedagogical Ideas as Most Important to You as an Educator

There is an even distribution between which pedagogical path is best: putting the group’s needs or the individual’s needs in the centre. The opinions are evenly distributed here, with a slight predominance towards the group-oriented (Table 13). The staff values the children’s interaction and play with each other as more important in building a sense of belonging than the staff acting as role models (Table 14).

Table 13.

Pedagogical ideas as most important to educators.

Table 14.

Pedagogical ideas as most important to children.

5.13. 12. Please Rank These Specific Pedagogical Practices in Order of Importance

The most valued ways the teachers can help the children get a sense of belonging in preschool are for them to act as adult role models and to get the children to listen to each other. The strategy of teaching about differences is believed to be less useful (Table 15).

Table 15.

Pedagogical practices in order of importance.

5.14. Results from the Open Questions

The answers from the three open-ended questions were few and brief. Forty respondents (22%) commented on the first open question: “If you could make changes to promote belonging for children in (pre)school what would it be?” Of these, 31 requested more resources. Some comments were about dialogue, education and competence. There were 18 responses on the second open question: “What else would you like to tell us about belonging in your (pre)school?” Nine responses mentioned the importance of consensus on goals and values and child views. Five responses repeated the need for smaller groups or more staff resources.

5.15. Correlations

To investigate whether there were any connections between the factors, a correlation analysis was performed. Such an analysis aims to investigate whether there is a relationship between two variables where the direction and strength of the relationship varies between the values −1 and +1. The Pearson correlation coefficient is the most widely used. It measures the strength of the linear relationship between normally distributed variables. Values such as 0.21–0.4 can be considered as weak relationship and values between 0.41–0.6 as medium strength relationship [].

There are a number of positive relationships between the factors, with all correlations significant at the 0.05 level ** (Table 16).

Table 16.

Correlations between the factors.

The first correlation reported in the table above indicates that staff who experience an open atmosphere in the workplace and who are confident in their professional role and practice (factor 1) feel the trust and support shown by parents for the preschool programme (factor 6b). The same staff also experience clear support for the idea of inclusion from the municipality and current national policy (factor 7).

5.16. Factors 2a, b, c

It is clear that staff who feel the groups of children are too large and the staff too few (factor 2a) are doubtful about the mission of inclusion (factor 5). The same group also feels that their teacher education regarding children with special needs is insufficient (factor 2b) and that the organisation builds in problems that prevent inclusion through the premises, furnishings and activities (factor 2c).

5.17. Factor 4

The staff’s concerns and doubts about the possibilities for inclusion (factor 5) are related to the staff’s lack of confidence in the children’s independence, social competence and ability to take responsibility (factor 4a). This lack of trust is also associated with weak confidence in the municipal support and the national policy for preschools (factor 7).

5.18. Factors 6a, b

Staff who believe the parents’ influence and participation are important for the inclusion process (factor 6a) also have the feeling that parents share this view (factor 6b). Staff who are very confident in the municipal support and the national policy also have the feeling that parents back their work.

5.19. Differences between Groups and Backgrounds

Based on the background variables included in the survey, profession, age and number of years of service, the mean value in the responses was compared based on the factors reported. With the majority of the respondents being preschool teachers and childcare workers, their answers were compared. The respondents’ ages were divided into two classes, as well as experience in the profession (Table 17).

Table 17.

Comparison of mean based on profession, age and number of years in service.

The preschool teachers who responded to the survey experience greater affiliation with the preschool than the childcare workers. This is also true for staff in the higher age range and those with longer experience (factor 1).

In relation to childcare workers, the preschool teachers are less satisfied with the teacher training and further education. Staff with longer professional experience are also less satisfied than those with less experience (factor 2b). In comparison with childcare workers and staff with less experience, the preschool teachers and staff with longer experience to a greater extent judge that the organisation puts up barriers to inclusion (factor 2c).

The preschool teachers’ answers show greater confidence in the children’s ability to include and interact, which also applies to the younger staff (factor 4). The opportunities to build an inclusive environment are valued more by preschool teachers than by childcare workers (factor 5).

6. Conclusions

6.1. Goals and Values

The staff are very confident in the society’s attitude and stance toward an inclusive programme. The support and resources from the municipality do not receive the same positive assessment as the national policy. Many staff believe that special teachers support the policy, but there is a lack of resources and skills training for preschool staff. Most likely this is due to differences between the national intentions and the commitment and finances for conducting preschool programmes in the various municipalities.

According to the interviewees, the goal for all children to feel a sense of belonging and be accepted is strongly held by preschool culture and other citizens. The staff who feel secure in their work situation feel a clear support from the state and municipality about working toward an inclusive programme.

6.2. Tasks and Activities

There are few respondents who judge that the preschool tasks and activities build obstacles to inclusion. This indicates that the preschool physical environment and programme are usually well adapted to carrying out an inclusive programme. Preschool teachers as a group have greater demands for an inclusive environment, as do staff with more experience. It is possible that the group with more experience of the programme or higher education better sees how the environment can be developed.

The staff value the children’s interaction and play with each other as more important in building a sense of belonging than the staff acting as role models.

6.3. Educators

It is clear that the majority of those who responded to the survey think that there is a lack of staff resources to be able to ensure the goal of all children feeling a sense of belonging in the preschool group. The groups are perceived by many as too large.

A significant part of the staff believe that they do not have sufficient skills to support children with special needs. Many believe that the teacher education is inadequate at providing staff the knowledge and competence to meet children who need special support. Further education that can compensate for this shortcoming is insufficient, according to the same percentage of respondents. The preschool teachers and staff with longer professional experience have expressed a greater need for education, which in the first case may be due to feeling an overall responsibility for the programme and secondly that the education is of a later date.

More than half of the respondents are concerned about how best to carry out supportive efforts and that the time for this is not sufficient. Many see themselves as able to carry out this mission now but are concerned about whether it will occur in the right way and how it will develop in the future. The majority of respondents believe that children can communicate and create a situation that includes children with special needs. Staff with this view of children, mainly preschool teachers and younger staff, have a clear positive attitude toward the preschool being able to create a sense of belonging in the group. The same staff believe that it is more important to discuss differences based on the children’s feelings than for the staff to convey facts about the idea.

Nearly one-third doubt the children’s ability to include other children, for example, by taking other children’s perspectives and standing up for their rights. This attitude is reflected in the doubts about the possibilities for the preschool to realise the goals for inclusion. The doubt is stronger among the childcare workers.

7. Grouping, Peers

A cautious interpretation of the answers about reasons why children exclude other children is that this exclusion is not considered to be very common. According to the staff, language and social status are the factors considered to be the “most frequent” reasons why children exclude other children. It is clear that language and communication are central to inclusion.

8. Environment and Resources

The atmosphere at the preschool is perceived by the majority of the staff as open and permissive, and the absolute majority of the respondents feel a sense of belonging to the preschool. They experience being able to discuss issues about inclusion, but there is some uncertainty as to whether all colleagues are open and honest in these discussions.

It is clear that the majority of the staff think that there is a lack of resources to support working toward all children feeling a sense of belonging in the preschool group. The staff who clearly have doubts about the idea of inclusion are critical of group size, staff dimensioning, training efforts and obstacles in activities and the physical environment. The same staff do not place the same trust in the children’s ability to work for inclusive activities.

9. Parents

The respondents assess that it is easier to feel a sense of belonging to the preschool activities if the parents have roots in Swedish culture. Many believe that parents with an immigrant background have less sense of belonging. According to the staff, the values that the preschool conveys are shared by the parents.

Parental cooperation in the form of information and communication is very important, believe a predominant percentage, but not as many invite the parents to discussions about goals and planning for an inclusive programme. The staff who experience an open atmosphere in the workplace and who are confident in their professional role and practice also have a sense of support from the parents. Satisfied parents strengthen the perception that teachers are doing a good job. When the staff give the parents influence in activities, they transfer to them trust and a positive attitude towards an inclusive preschool.

9.1. Limitations of the Study and Important Experiences for Future Studies

The response rate was very low in this study, which probably has many explanations. There was low participation in all the countries that conducted the survey. When many countries collaborate in an investigation and there is the aim of making the survey as uniform as possible, there are necessary adjustments and compromises according to the conditions of all participating countries. This can lead to formulations that do not really correspond to the culture and context of one’s own country. The ambition to obtain answers to as many questions as possible made the survey comprehensive. Even though the majority of questions were multiple-choice (90%), many respondents felt that it was too time-consuming. The survey is clearly redundant, with many questions and formulations being similar. Some respondents commented that the question logic often changed, and that the majority of questions were expressed in a negative form. This can possibly strengthen the reliability, though simultaneously, there is risk of greater dropout as the number of questions increases, and in some cases, these choices can provoke the respondent. Another problem is that formulations and concepts well-known in the academic world can be perceived by preschool staff as foreign and difficult to interpret.

Perhaps the researchers’ understanding of preschool culture has decreased, and the distance and contact between academia and the field have increased. In Sweden, one can discern a certain distrust of universities, as many municipalities politely refused the researchers’ request for participation. Several municipalities explained that they would rather save their staff’s involvement for their own evaluations and that the workload in preschools is already high. Others from the field say that the results after concluded studies are communicated in a way not very suitable to the preschool programme (for example, scientific journals in English). This background lends important experiences to bring into future investigations, with increased closeness to and knowledge of the respondent being a key part.

9.2. Pedagogical Implications

It is clear that the factors forming the basis for the study have varying degrees of significance for how well staff create an inclusive programme. It has been clarified that certain areas have a greater impact on goal fulfilment from an inclusive perspective. This study confirms that staff’s work environment, fundamental values and working methods are extremely important, which previous surveys have also reported [,,,,]. There is also reason to believe that preschool children, whether as a group or an individual, are underestimated as a power source in building a sense of belonging for all children. Increased confidence in their abilities is likely to lead to a better outcome in this endeavour.

A large part of the staff who responded to the survey feel that the atmosphere is good at the preschool and that they do express their opinions regarding inclusion. These same respondents are unsure whether all colleagues share this view. From the data, it is not possible to see how much agreement there is in one preschool department, but if the answers were transferable, it appears that one-third of the staff doubt the possibility of succeeding with an inclusive programme. This may mean that important differences of opinion are not visible; part of the staff group might hold a pedagogical attitude that is not fully supportive. Perhaps one refrains from discussing something contrary to the official position and thus avoids conflict. To take this issue further, the preschool principal needs to initiate discussions that go deeper and involve all employees.

A large part of the staff has low confidence in the central administrations of the municipalities, as many feel they lack sufficient and concrete support. It is therefore crucial for the municipalities to be attentive to shortcomings and work to increase trust in the central management.

The majority of respondents believe that the physical environment does not put up major obstacles to an inclusive activity, as previous studies have shown. Probably the physical environment at most preschools is well designed and appropriate, while there could be some preschools that have not been as successful. It is therefore important to take advantage of other preschools’ successes in this respect in the planning of new preschools [].

There is a clear demand for more staff and/or smaller groups of children. It is unlikely that staff who did not participate in the study have a different opinion. Lack of resources makes staff doubt whether it is possible to realise an inclusive programme. This opinion is clearly marked in the multiple-choice questions and is the most frequent comment in the open-ended items. Several studies also confirm this attitude [,,], which should not be neglected in the future, but treated as a prerequisite for fulfilling the stipulated goals. When resources are made available, it is important that the funds are reserved and directed to an inclusive way of working and that the reinforcement of a segregating attitude is not permitted [,].

There is a clear desire for strengthening the special education in teacher training. In preschool teacher education, special education is rather separate from other pedagogy and covers a smaller part of the education programme. In order to build the confidence necessary to work with special needs children, this part of teacher training must be strengthened. It is also crucial to increase continuing education efforts with special educational content for preschool staff, with value-based issues receiving considerable attention. Without these measures, more responsibility will probably fall on the special educators in the preschool, and then children with special needs become more of a special assignment. The staff oftentimes are worried about children in need of special support, which in itself is a sign of care and concern, but also evidence that more efforts are needed in the area. Relieving the concern by creating special activities would be an embarrassing mistake.

According to the survey results, preschool children have a high acceptance for differences as defined by adults and educators. That relatively many respondents have shown uncertainty on questions regarding whether or not language makes children exclude other children, indicates that this may be a bigger problem than what this study shows. It would be interesting to try alternative forms of communication, particularly in groups characterised by varying language backgrounds.

Building good parental contact and involvement benefits an inclusive environment. There is room for trying new solutions for cooperation, and it is particularly important to improve contact with parents with other cultural backgrounds.

The staff, who trust the group of children’s own ability to create a sense of belonging for all children, show a more positive attitude toward having the conditions to succeed. This is an interesting result that indicates that this pedagogical view, in addition to methods choices, has real significance for the success of an inclusive preschool. Staff can take hold of this finding and give children room for their own initiatives with contacts and activities; that is, according to the study results, giving children more influence and trust promotes an inclusive programme.

9.3. Future Study

The present study has generated interesting findings and valuable methodological experience, which are important to take advantage of in investigating further. Therefore, going forward with a more classroom-based and development-oriented study that involves all staff in valued discussions is a logical continuation. The next step will be to test inclusive working methods in projects that involve children, staff and parents, as all actors have been judged to be very important for meeting the goal of an inclusive programme.

Funding

This research was funded by NordForsk grant number 85644.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee “Regionala etikprövningsnämnden, [Regional Ethics Review Board] Linköping, Sweden” Dnr 2018/208-31 2018-05-15.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Karlsudd, P. The Search for Successful Inclusion. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2017, 28, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stukat, K.G. Conductive education evaluated. Eur. J. Spéc. Needs Educ. 1995, 10, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelsson, I. Integrering—bevarad normal variation i olikheter. In Boken om Integrering: Ide, Teori, Praktik; Rabe, T., Hill, A., Eds.; Corona: Malmö, Sweden, 1996; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, G. Educational psychology and the effectiveness of inclusive education/mainstreaming. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 77, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, S. The Effect of Teachers’ Attitude toward Inclusion on the Practice and Success Levels of Children with and without Disabilities in Physical Education; University of North Carolina: Wilmignton, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dysthe, O. Dialog, Samspel och Lärande; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrbo, I. Idén Om en Skola för Alla och Specialpedagogisk Organisering i Praktiken; Actauniversitatis Gothoburgensis: Göteborg, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, L. Teaching Strategies: For Some or for All? Kairaranga 2006, 7, 724–727. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsudd, P. Family interaction and consensus with IT support. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, J. Pedagogical documentation: The search for children’s voice and agency. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, B.; Persson, E. Inkludering och Måluppfyllelse—Att Nå Framgång Med Alla Elever; Liber AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, C.; Topping, K.; Jindal-Snape, D.; Norwich, B. The importance of peer-support for teaching staff when including children with special educational needs. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2011, 33, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.A. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsudd, P. Looking for Special Education in the Swedish After-School Leisure Program Construction and Testing of an Analysis Model. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reite, G.N.; Haug, P. Conditions for academic learning for students receiving special education. Nord. Tidsskr. Pedagog. Krit. 2019, 5, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickerman, P. Including children with special educational needs in physical education: Has entitlement and accessibility been realised? Disabil. Soc. 2012, 27, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, E.; Kalyva, E. The influence of teaching experience and professional development on Greek teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion. Eur. J. Spéc. Needs Educ. 2007, 22, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, H.; Celiköz, N.; Secer, Z. An analysis of pre-school teachers’ and student-teachers’ attitudes to inclusion and their self-efficacy. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2009, 24, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, A.; Pijl, S.J.; Minnaert, A. Regular Primary Schoolteachers’ Attitudes towards Inclusive Education: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 15, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalaki, E.; Kourkoutas, E.; Hart, A. Building inclusion and resilience in students with and without SEN through the im-plementation of narrative speech, role play and creative writing in the mainstream classroom of primary education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Johnson, J. Integrated but not included: Exploring quiet disaffection in mainstream schools in China and India. Int. J. Sch. Disaffect. 2008, 6, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Mustapha, R.; Jelas, Z. An empirical study on teachers’ perceptions towards inclusive education in Malaysia. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2006, 21, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Singhania, R. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Indian J. Paediatr. 2005, 72, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuckle, P.; Wilson, J. Social relationships and friendships among young people with Down’s syndrome in secondary schools. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2002, 29, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asp-Onsjö, L. Specialpedagogik i en Skola för Alla. In Lärande, Skola, Bildning; Lundgren, U., Säljö, R., Liberg, C.C., Eds.; Natur & Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Philips, D.C.; Soltis, J.F. Perspectives on Learning; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Molin, M. Att Vara i Särklass: Om Delaktighet och Utanförskap i Gymnasiesärskolan; University Electronic Press: Linköping, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, P.T.; Ainscow, M.; Howes, A. Inclusive education for all: A dream or reality? J. Int. Spec. Needs Educ. 2012, 7, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Szönyi, K. Särskolans om Möjlighet Eller Begränsning-Elevperspektiv på Delaktighet och Utanförskap; Pedagogiska Institutionen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brodin, J.; Lindstrand, P. Perspektiv på en Skola för Alla; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth, F. Pedagogisk Dokumentation—En Pseudoverksamhet? Lärares Arbete Med Dokumentation i Relation Till Barns Delaktighet; Linnaeus University Press: Vaxjo, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Linikko, J. Det Gäller att Hitta Nyckeln—Lärares Syn på Undervisning och Dilemma för Inkludering av Elever i Behov av Särskilt Stöd i Specialskolan; Stockholms Universitet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bråten, I. Vygotskij Och Pedagogiken; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nilholm, C. Specialpedagogik. Vilka är de grundläggande perspektiven? Pedagog. Sver. 2005, 2, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Frithiof, E. Mening, Makt och Utbildning: Delaktighetens Villkor för Personer Med Utvecklingsstörning; Universitet: Växjö, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dockrell, J.; Shield, E. Acoustical Barriers in Classrooms: The Impact of Noise on Performance in the Classroom. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 32, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deris, A.R.; Di Carlo, C.F. Back to basics: Working with young children with autism in inclusive classrooms. Support Learn. 2013, 28, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolverket—Swedish National Agency for Education. Vad Påverkar Resultaten i Svensk Grundskola? Kunskapsöversikt om Betydelsen av Olika Faktorer; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tideman, M. Normalisering och Kategorisering: Om Handikappideologi och Välfärdspolitik i Teori och Praktik för Personer Med Utveck-Lingsstörning; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsudd, P. Tablets as learning support in special schools. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2014, 59, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. What Really Works in Special and Inclusive Education; Routledge: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Morrone, M.H.; Matsuyama, Y. A Hopeful and Sustainable Future: A model of caring and inclusion at a Swedish preschool. Child. Educ. 2020, 96, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsudd, P. When differences are made into likenesses: The normative documentation and assessment culture of the preschool. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M. Förskolans Dokumentations-och Bedömningspraktik: En Diskursanalys av Förskollärares Gemensamma Tal om Dokumenta-tion och Bedömning; Linnaeus University Press: Vaxjo, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wah, L.L. Different strategies for embracing inclusive education: A snapshot of individual cases from three countries. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2010, 25, 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gadler, U. En Skola för Alla—Gäller det Alla? Statliga Styrdokuments Betydelse i Skolans Verksamhet; Linnaeus University Press: Vaxjo, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J. Pedagogies of Educational Transition: Educator Networks Enhancing Children’s Transition to School in Rural Areas. Ph.D. Thesis, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Hammond, L.; Bjervås, L. Pedagogical documentation and systematic quality work in early childhood: Comparing practic-es in Western Australia and Sweden. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, M.D. Värdeladdade Utvärderingar: En Diskursanalys av Förskolors Systematiska Kvalitetsarbete; Linnaeus University Press: Vaxjo, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, R.E. Att Synliggöra det Förväntade: Förskolans Zrformativ Kultur; Linnaeus University Press: Vaxjo, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nilfyr, K.G. Dokumentationssyndromet: En Interaktionistisk och Socialkritisk Studie av Förskolans Dokumentations—Och Bedömningspraktik; Linnaeus University Press: Vaxjo, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld, T.; Hout, R. Statistics in Language Research: Analysis of Variance; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hermerén, G. God Forskningssed (Vetenskapsrådets Rapportserie; 2011:1); Vetenskapsrådet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, E.; Westerlund, J. Statistik för Beteendevetare: Faktabok, 4th ed.; Liber: Malmö, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Skolinspektionen. Förskolans Arbete Med Barn i Behov av Särskilt Stöd; Skolinspektionen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).