Abstract

In the context of education, ‘presence’—a state of alert awareness, receptivity and connectedness to what is happening in class—is related to depth of insight into the situation, and to more opportunities for action. Presence is mainly conceptualized in philosophical and theoretical terms and idealistic accounts. This study aims to gain understanding of teachers’ experiences of the emergence and manifestation of their own and students’ presence in their daily educational practice and insight into the significance they attach to presence. This is relevant because presence may contribute to teachers’ reflection-in-action and their ability to respond to classroom situations. Using a phenomenological approach, we interviewed 12 secondary teachers in the Netherlands about their lived experiences of presence. The participants relate presence to being concurrently attentive and aware of students and of themselves, to lively interaction, to relevant education and to students’ deep understanding of the subject matter and students’ personal development. In the discussion of the significance of presence, we suggest that research on presence might promote our understanding of how teaching may afford the coming together of students’ academic learning and their personal development. In addition, our findings are related to teachers’ professionalism and personal professional fulfillment.

1. Introduction

Presence indicates how people are involved in situations. When present, one is closely focused on the here and now, and one perceives and acts with all one’s being and all one’s senses, not merely rationally. As a temporal and situated concept, presence is related to depth of insight into the situation and to more opportunities for action [1,2]. In professional contexts such as organizational change and health care, presence is considered as indicative of transformational learning [3] and the well-being and personal growth of those concerned [4]. Scholars have emphasized the value of presence because they acknowledge the active involvement of participants—whether professionals, clients, or students—in interactive professional situations.

Presence is not a new concept in education. Scholars such as Dewey [1], Greene [5] and Noddings [6] have referred to presence in their writings. Albeit on a small scale, presence has recently become an emerging topic within educational research. This aligns with an increase in attention in educational research to the interactive educational process involving coalescence of the teacher and the students as unique singular beings, the teaching method, the subject matter, and the unique circumstances [7]. Presence is consistent with an approach to education in which what is educationally desirable for what purpose cannot be totally predetermined and depends on factors that are unique to the situation. Inherently, unpredictability and uncertainty are acknowledged as significant features of teaching [8]. Similarly, in educational philosophy, a renewed attention to a phronesis–praxis perspective on education is observable. Praxis refers to ‘wise action’ in a practice that is comprehensive and open-ended [9]. Phronesis signifies ‘morally committed thought’ guiding this action. A phronesis–praxis perspective refers firstly to forms of knowledge, that are “pragmatic, variable, context-dependent, and oriented towards action” [10] (p. 2). Secondly, it includes a moral component referring to teachers’ commitment to do their best and to act for the good of students and for the greater good in society [10]. In the context of these developments in educational research and philosophy, teachers’ estimations and judgments are considered essential [8]. Such an approach is reflected in discussions of the practices of teacher noticing [11], their reflection-in-action [12], and teachers’ professional judgment [13,14]. We argue that within this situated and complex notion of teaching, presence may play an important role. We have three reasons for this. First, presence may contribute to teachers’ ability to approach the unavoidable uncertainties of teaching practice in a thoughtful and reflective way [12,15]. Kemmis [16] (p. 155) argued that phronesis—as guiding wise action—consists in “openness to experience—a preparedness to see what the situation is, in what may be new terms or new ways of understanding a situation”. This ‘openness’ and ‘preparedness to see’ has similarities with presence as a state of alert awareness, receptiveness, and connectedness to what is happening in class. Earlier studies have suggested that presence enhances teachers’ sensibility to and insights into the classroom situation [17,18]. Second, the concept of presence offers an inclusive focus on students’ broad development. Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] related presence in teaching to students’ academic learning, personal development, and to moral purposes of education. Third, a study by Meijer, Korthagen and Vasalos [19] suggested that presence contributes to a connection between the personal and professional aspects of teaching, to self-confidence, and to the ability to respond to classroom situations.

Presence seems an interesting concept for enhancing our understanding of teachers’ professionalism and of the realization of broad educational aims. However, to date, insights into presence in the context of education have been mostly based on philosophical and theoretical understandings and idealistic accounts. We do not yet know whether and how teachers experience presence in their daily practice and what significance they attach to it. This paper seeks to gain an understanding of secondary school teachers’ experiences of presence in their daily educational practice. In that way, we may contribute to a further conceptualization of this hitherto elusive concept within the context of education.

2. Theoretical Background

Recently, educational researchers have started to address presence in teaching, both conceptually and, to a limited extent, empirically. Among these few, Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] conceptualized ‘presence in teaching’, drawing from educational philosophy and research, psychology, arts, and religion and using limited data from interviews and papers from (student) teachers. They defined presence in teaching as:

A state of alert awareness, receptivity and connectedness to the mental, emotional and physical workings of both the individual and the group in the context of their learning environments and the ability to respond with a considered and compassionate best next step.[17] (p. 266).

In this definition, presence implies a particular state in which perceiving and responsive acting are intertwined. This merging of perception and action is similarly expressed in the definition below:

Being present (…) is a way of encountering the world of the classroom (or nature, a piece of music, or another person), but it also includes a way of acting within it whereby the action that one takes comes out of one’s sensitivity to the flow of events.[20] (p. 235).

The term ‘state’, within the first definition, refers to presence as a phenomenon that is temporal. Citing Martin Buber, Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] (p. 284) argued that: “Presentness (…) arises when the ‘Thou becomes present’, when one comes to see the other and allows one’s self to be seen”. This quote, in addition, illustrates that presence is embedded in and emerges in interaction. Presence then, is also a relational phenomenon. For this study, we embrace this first definition of presence in teaching as being the most comprehensive and substantiated.

Scholars have predominantly confined themselves to presence in teaching [17,18,19]. We argue that presence is not just a state relevant to the teacher. Building on constructivist and sociocultural theoretical approaches, scholars have come to acknowledge students’ active role in classroom interactions in knowledge construction and meaning making [17,19]. In their conceptualization of presence in teaching, Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] positioned presence within the relation between teacher, student, and subject matter, and emphatically took students’ active role into account. They articulated that students need to be involved in experiences that offer them the opportunity to experiment, to interact, and to question. A relationship of trust constitutes the ground on which students are able to build their own ideas and make meaning of their own experiences. Because of the importance of the students’ active role, we underscore the value of the students’ presence, that is, their alert awareness, receptiveness, and connectedness to the subject matter, the teacher, and their fellow students in the educational process [21]. A reason for this is that the greater range and depth of insight and increased opportunities for action—as related to presence—may contribute to a deepening of students’ knowledge construction and meaning making.

There are a few concepts related to presence that we briefly address here. The first is ‘pedagogical tact’, which refers to teachers’ sensitive pedagogical actions on the spur of the moment [22]. Like presence, pedagogical tact ties in with a way of thinking about education in which the relation and interaction between teachers and students, as well as students’ personal development, are considered important. However, in the literature on pedagogical tact the focus seems to be on how the teacher can do what is good for the child’s being and becoming. Presence, as a state of alert awareness, receptivity, and connectedness, opens up the possibility of taking into account teachers’ as well as students’ presence in interacting with each other and the subject matter. A more nuanced discussion of the concept of pedagogical tact in relation to presence is needed, but goes beyond the scope of this paper. There are also similarities between presence and the concept of ‘flow’, especially in the merging of perception and action [23]. The main difference in our view is the moral purpose of presence. While flow is predominantly conceptualized as an optimal individual experience for personal benefit, presence in education is explicitly directed at the development of students in relation to their role in society.

The notion of presence is in keeping with a relational paradigm of teaching and learning based on an understanding that students do not learn merely from the application of the pedagogical method or the textbook, or from their own independent learning activities, or as a result of the teacher’s qualifications or experience. Rather, the healthy and trusting relationships between teacher, students, and subject matter facilitate robust and enduring learning [24]. Here, we see a concurrence with the central and northern European tradition of Didaktik, where meaning is conceived of as something that cannot be pre-defined but is constructed on-site in a classroom based on the methodological decisions of a teacher [25]. The core of teachers’ professionalism within this tradition is concentration on the relations between the three corners of the ‘didactic triangle’: teacher, students, and subject matter [26]. This aligns with our view that presence is embedded in the interrelationships and interactions between teacher, students, and subject matter.

Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] discerned three dimensions of presence in teaching: presence as connection to self; presence as connection between teacher and students; and presence as teachers’ focused attention on how students deal with the subject matter. Their conceptualization of presence as embedded in the interaction between teacher, students, and subject matter offers points of departure to explore teachers’ experiences of student presence, as well. Therefore, we will structure the continuation of our theoretical background through the heuristic of these dimensions of presence.

2.1. Presence as Connection to Self

The first dimension, “Presence as connection to self,” is a key element of presence in teaching and forms the basis for the connection to students [17]. Similarly, Meijer et al. [19] conceived of presence as “being-while-teaching” in a study of a single student teacher developing presence while supported by supervision sessions. Due to deepening self-awareness, this student teacher was able to teach more responsively. An integration of the personal and professional self is crucial for teachers’ trust in themselves [27,28]—and, thereby, their students’ trust in them—and for the ability to be present to the students and their learning [17]. Similarly, and informed by Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological concept of embodied consciousness, Greene [5] explicitly emphasized the significance of being present to oneself—to one’s history and perceptions—for one’s experience and knowledge of the world.

Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] emphasized the importance of the connection of teachers’ self to social and moral purposes with regard to the welfare of others and the larger society, more specifically, a democratic society. Referring to Dewey, they argued that “teaching must have an ‘end-in-view’ that is moral” (p. 273).

Teachers’ connection to self may have both an embodied and a conscious character. Based on an analysis of teachers’ stories about their bodies in autobiographies, Estola and Elbaz-Luwisch [29] regarded presence as explicitly embodied, holding that every action and reaction of the ‘present’ body is a meaningful signal about teaching practice. Pointing to both the embodied and conscious character of presence, Solloway [18] referred to teachers’ awareness of their bodily experiences and reflections on their meaning, so as to be open to new imaginings. She studied the presence teachers developed by receiving training in mindfulness. By focusing on self-knowledge, Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] seemed to refer to a conscious and discursive mode for these elements of the connection to self.

2.2. Presence as Relational Connection

Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] argued that teachers must assume a relational stance to students that includes empathy with and attunement and responsiveness to “the subjective inner experience” of the students at “both a cognitive and affective level.” Presence as relational connection has likewise been emphasized in educational philosophy by Greene [5] and Noddings [6], who both highlighted the significance of teachers’ engagement with students as individuals, each with a personal lifeworld.

The relational connection has three elements. First, the focus is on the here-and-now encounter between teacher and students as expressed by Noddings [6] (p. 199), who conceived of presence as a fundamental feature of ‘care’: “What I must do is to be totally and non-selectively present to the student—to each student—as he addresses me. The time interval may be brief but the encounter is total”. Second, presence implies a way of perceiving in which all the teacher’s being is involved with an openness toward students. In Art as Experience, Dewey’s [1] notion of “being fully alive” comes close to presence. With “aliveness” he referred to full attention, an open mind, openness of all the senses, and an active (inquiring) “hospitality” to new ways of seeing and understanding [30]. Applied to teaching, this means that the teacher is alive to what students say by words and body language as well as sensitive to the meaning of their expression [15]. Teachers’ openness of the senses was emphasized as well by Solloway [18], whose study on mindfulness in relation to teacher presence revealed the importance of teachers’ receptiveness and non-judgmental attention to students. Third, interpersonal trust is an essential feature of this dimension, which “engenders confidence in the student’s capacity to trust herself as a learner, thinker and creator” [17] (p. 275).

Central in this dimension is that students feel seen and understood, cognitively, emotionally, and physically, and are encouraged to make meaning of their own experiences.

2.3. Presence as Pedagogical Connection

Presence as pedagogical connection makes clear that the relation between teacher and students does not exist for its own sake. There is always a connection with the subject matter and the educational purpose of students’ broad development. This dimension concerns the teacher’s focus on students’ engagement with the subject matter and thus indirectly the teacher’s connection to the subject matter and the students both as individuals and a group. Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] related this dimension of presence to Dewey’s notion of reflection. According to them, presence entails observing the students at work, analyzing and responding with an intelligent action. Although observing and analyzing—as a more distanced way of perceiving—are crucial elements of presence, in our view this pedagogical connection also includes teachers’ active engagement in the interaction with students and subject matter. Presence may as well become manifest in teachers’ intuitive or embodied understanding of students’ learning based on this engagement [22,31].

The emphasis in this dimension on students’ engagement with the subject matter suggests presence of the students as well. This may become manifest in their attentiveness and connectedness while experimenting, questioning, making mistakes, and interacting with the subject matter, the teacher, and fellow students. But how are students encouraged to be attentive and connected? How are teachers able to be present to them? After all, presence may not emerge automatically or in a vacuum. Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] particularly directed attention to teachers’ deep subject matter knowledge as well as their knowledge and understanding of students as individuals and as a group. Both are considered necessary in order for teachers to be free to closely attend and attune to students’ engagement with the subject matter and “to connect students to an appropriate point of entry” [17] (p. 280). Whether and how other aspects may affect the emergence of presence is as yet unclear. The same applies to how teacher and students may stimulate presence in a reciprocal way.

Finally, Rodgers and Raider-Roth [17] suggested that presence in teaching promotes students’ academic learning as well as their personal growth. However, they did not elaborate on this significance of presence, which may be directly related to students’ presence and not merely and indirectly to presence in teaching.

Overall, our current knowledge of presence in the context of education is primarily based on philosophical and conceptual understandings. We do not yet know how teachers experience presence of themselves and of their students in their daily practice. We distinguish the following components, allowing an open approach to teachers’ experiences. First, we focus on the emergence of presence and aim to analyze teachers’ experiences of their own, students’, and the subject matter’s contribution to presence, as well as their experiences of how it emerges from the interactional process. Second, we distinguish its manifestation: how do teachers experience the way their own and the students’ presence is manifest in daily educational situations? Third, we aim to gain insight into the significance teachers attach to presence for students as well as for themselves. Our research question is therefore:

How do secondary school teachers experience the emergence and manifestation of presence in their daily educational practice and what significance do they attach to presence?

3. Methodology

In line with our research aim to gain a deep understanding of teachers’ experiences of presence in their daily practice, we used a phenomenological approach in which teachers could describe and reflect upon their experiences through interacting with the interviewer [32,33]. Our assumption was that presence is found in intersubjective relations between teacher, students, and subject matter (the didactic triangle), and that teachers’ experiences of presence move in and through these intersubjective relations [34]. To capture a rich picture of teachers’ experiences of presence within this didactic triangle, we focused on teachers’ concrete experiences, in which presence is ‘lived through’ in daily practice [32]. We further assumed that the subjective lived experiences of a variety of teachers could provide insight into the general characteristics of their experiences—what do they have in common—as well as in the variations and nuances within their experiences [35]. In our approach, an open, ‘bridled’ attitude toward teachers’ experiences of presence, with yet interrogative work during the process of understanding their experiences, was emphasized [33]. This study took up the perspective of 12 Dutch secondary teachers, with whom we conducted 24 interviews.

3.1. Data Sampling and Participants

The purpose was to select teachers with an affinity for the phenomenon of presence in education, who would be able to reflect on and talk about their experiences of presence. For that reason, purposive sampling [36,37] was used to identify teachers matching these criteria. We asked experienced teacher-educators as experts to use these criteria to identify teachers from their network. To help them assess teachers, the first author had a preparatory meeting with each teacher-educator to provide information about presence in education, with a brief presentation on our theoretical background. From the 25 names the teacher-educators provided to us, we chose a variety of teachers for the sample in order to increase the variability of teacher perspectives (see Table 1 for an overview of the participants). All teachers we approached reacted positively to the subject of presence in education and were willing to participate, except for one who had a heavy workload.

Table 1.

Overview of participating teachers.

3.2. The Interviews

The purpose of the interviews was to explore in depth participants’ lived experiences of presence. The interviews were conducted by the first author. In a pilot study, we collected teachers’ primary associations with presence in their daily practice and discovered that the elusive term ‘presence’ offered a wide variety of interpretations. Therefore, in the final design we incorporated a preparation phase that enabled the participants to start with a clear sense of the phenomenon under investigation [34].

In the first meeting, the participants were familiarized with the content and design of the study and addressed by the researcher as experts to stimulate maximum openness, authenticity, and truthfulness [38]. We followed an informed consent procedure in which the participants were informed about the open nature of the interviews, the voluntary character of participation and the possibility to withdraw their participation and consent at any time, and about the anonymization and use of the data for scientific publication and presentation. Based on the theoretical notions of presence and our experiences in the pilot study, we used the following description of the study and of presence to inform the participants:

This research is about your experiences of the moments in which you feel that you and your students are fully in the moment or, in other words, are attentively involved with the subject matter and the purpose of education. We are interested in your concrete and possibly diverse lived experiences of your own presence as well of students’ presence occurring in teacher–student(s) interactions, peer interactions or students’ individual work.

The first interview started with the question: “Can you please tell me about such experiences you remember?” The experiences of presence they described were—at this stage—globally explored. Simultaneously, the interviewer checked whether the participants had an adequate picture of the type of experiences we were looking for (teacher as well as student presence). For example, when participants only referred to experiences of students’ presence, she asked for experiences of the teachers’ own presence as well. In order to obtain concrete stories of particular situations or events and to enable participants to give rich and detailed descriptions of their experiences [32], we ask them to prepare for the second interview over the following three weeks by recalling and collecting recent and diverse experiences of presence up to three months prior. The first interview lasted 30–45 min.

Three weeks later, in the second interview, we used these experiences as a starting point. This interview took the shape of a conversation in which the ‘gathered’ experiences were described and reflected upon by the participants through exploratory interaction with the interviewer. In our questioning, we ensured that the components of manifestation, emergence, and significance were explored for each lived experience addressed. For this purpose, the interviewer had learned several key questions per component by heart. Examples of these questions are: “What did you see/hear/feel/think at that very moment?” (Manifestation); “Can you please tell what preceded this experience of presence?” (Emergence); “Was it significant? If not, can you indicate why not? If it was, can you indicate for whom or for what?” (Significance).

In a majority of the interviews—in an unfolding process of description, memory, and reflection—participants mentioned several new insights for themselves. It is quite likely that the interviews also gave access to pre-reflexive structures of participants’ consciousness. During and after the interviews, ‘bridling’ [33] was explicitly applied by the first author by problematizing her own attitude and pre-understanding of presence as a teacher and as a researcher. The second interview lasted 75–90 min.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was inspired by the “Reflective Lifeworld Approach” of Dahlberg, Dahlberg and Nyström [33]. Data were analyzed by the first author using the following successive steps: familiarization with the data, analytical structuring, and, finally, developing themes. These different steps must not be understood as strictly sequential, but as a continual back-and-forth movement between focal meaning and the whole, between the emerging codes and themes, and the relations between them. Indeed, the hermeneutic circle was used throughout the entire process [39]. The first author bridled her understanding of teachers’ experiences of presence throughout the entire data analysis process by taking on a reflective, open stance so as to restrain herself from making “definite what is indefinite” [33] (p. 121). We aimed for a combination of “seeking and remaining open to receive” [34] (p. 68).

3.3.1. Familiarization with the Data

All interviews were video-recorded and transcribed verbatim, resulting in 332 pages of transcripts. The data collected after our explanation of the study in the first interview were included in the data set. The first step was immersion in the raw data by reading and re-reading the transcripts in order to get acquainted with the data.

3.3.2. Analytical Structuring

Here, the character of the reading changed and was directed at the meaning of the parts. First, data were divided into meaning units. These could vary in length from one line to a paragraph. Local codes—close to the participants’ concrete descriptions in the transcripts—were given to the meaning units. Initially, we developed local codes, such as “Having fun together”, “Students were focused on each other” and “Exploring the subject matter together with the students”. These meaning units and local codes were then condensed and abstracted to form codes that reflected a common set of features. This was done by a dynamic process of going backward and forward between the concrete and the abstract. For example, the aforementioned local codes were clustered into the code “Togetherness”.

The next step was to organize the coded meaning units according to the components of “Emergence”, “Manifestation”, and “Significance”, which thus structured the coding process. Almost all coded meaning units could be assigned to these three components directly. However, some coded meaning units could be assigned to both manifestation and emergence. For example, this was the case with the initial coded meaning unit “T: Attending to students as learners and persons” (“T” refers to teacher). In this phase, it became evident that it was important to differentiate between participants’ “Focus on students’ learning and experiences” when being present (Manifestation) and their “Comprehending and attuning to students” as part of their lesson preparation or of what they intended to do in general (Emergence). When this type of need to differentiate occurred, these meaning units were divided and coded again by using existing codes or new codes.

As we wished to remain as open as possible to participants’ experiences of presence, the explicit theoretical reflection on our results was postponed to the final stage of data analysis. Theory informed our interpretive understandings of participants’ experiences of presence [34] and illuminated meanings that were present in the data but that we had not discovered before [33]. For example, by applying the three dimensions of connection to our results, we saw one major new element of teachers’ experiences of presence, namely, teachers’ self-awareness. This resulted in the modification and recoding of “T: Teachers’ educational aims” to “T: Self-awareness”, more broadly referring to their in-the-moment awareness of feelings, thoughts, aims and tensions and its importance to their responsive acting.

Finally, we analyzed the variations in each code across the lived experiences. For example, the code “T: Focus on students’ learning and experiences” reflected a general characteristic, but it played out in various ways, as in the emphasis participants placed on students’ learning, their feelings (for example, interest, self-confidence), or their unique perspectives.

3.3.3. Developing Themes

In line with our aim to illuminate the abstract and general characteristics of participants’ experiences, we combined and sorted into themes the codes within each component that seemed to share unifying features. A theme that was characterized by the manifestation of students’ presence was initially named “Students’ active engagement” and a theme capturing the manifestation of teachers’ presence was labeled “Teachers’ attentiveness and awareness as whole persons”. Because interaction was a prominent part of the participants’ experiences, we also created a theme that reflected how presence was manifest in classroom and peer interactions, initially labeled as “Interacting dialogically”.

In line with our aim to illuminate how the codes were interrelated within and between the themes, we reviewed the transcripts again. In this way, it became clear that an interplay of multiple codes was involved in every lived experience of presence. For example, within the component “Emergence”, the code “Contextualizing teaching” was interrelated in almost all cases with “Comprehending and attuning to students” and in many cases with “Creating space and giving direction” and “Students’ expression”. As a result, we gained insight into the various ways the codes interacted within the lived experiences of presence.

This analytical step revealed a different status for the codes within the component “Significance”. These codes reflect the overarching significance participants attached to presence. When discussing significance, the participants transcended their particular lived experiences and referred to the overall significance they attached to presence in class.

The ‘thematic map’ was refined over a few iterations: the first author reviewed themes in relation to the coded data and the entire data set until we had captured the most important and relevant elements of the data in relation to the research question. After this, all themes were defined and renamed. Within the component “Manifestation”, our final label for students’ presence was “Students’ active and meaningful engagement”, to reflect how their mental, emotional, and physical engagement were related to making connections with the subject matter. Our final label for teachers’ presence was their “Full attentiveness and awareness”, to highlight the interplay of their attentiveness and awareness of students and of themselves. We renamed “Interacting dialogically” as “Lively interaction”, aimed at including as well the situations in which a wordless togetherness was experienced. Finally, when moving back and forth between themes, codes, and data, no new or further insights in the themes and codes were found.

3.4. Ensuring Quality

The following activities were undertaken to ensure the quality of the data analysis. First, peer-debriefing with all authors was organized—once every six weeks—to extensively discuss the findings, to monitor bias by bridling aimed at interrogating our understanding as meaning was being produced [33], to revise the findings, and to affirm their credibility [40]. These peer-debriefing sessions led to differentiation and specification of the themes. Second, the reliability of the final thematic map was determined at the level of the codes by having 15% of all the meaning units also coded by a second researcher. This researcher was familiar with the field of educational research, but had neither content-specific knowledge nor involvement in the research. This led to a discussion on some minor inconsistencies and differences in interpretation and a joint decision on the final formulation of the themes and the codes within these themes.

Finally, by means of an audit trail we sought to consciously consider, improve, and evaluate the quality of the entire research process. The first author described considerations, decisions (visibility), and their underpinnings (credibility) in order to substantiate the acceptability of the research decisions [40,41]. This audit trail was regularly and extensively discussed with all authors.

4. Results

The three components of teachers’ experiences of presence in their daily educational practice—emergence, manifestation and significance—structure the description of the results. We elaborate on each component by describing the themes, the similarities and variations that we found within them, and the interplay between the themes and codes within each component.

4.1. The Emergence of Presence

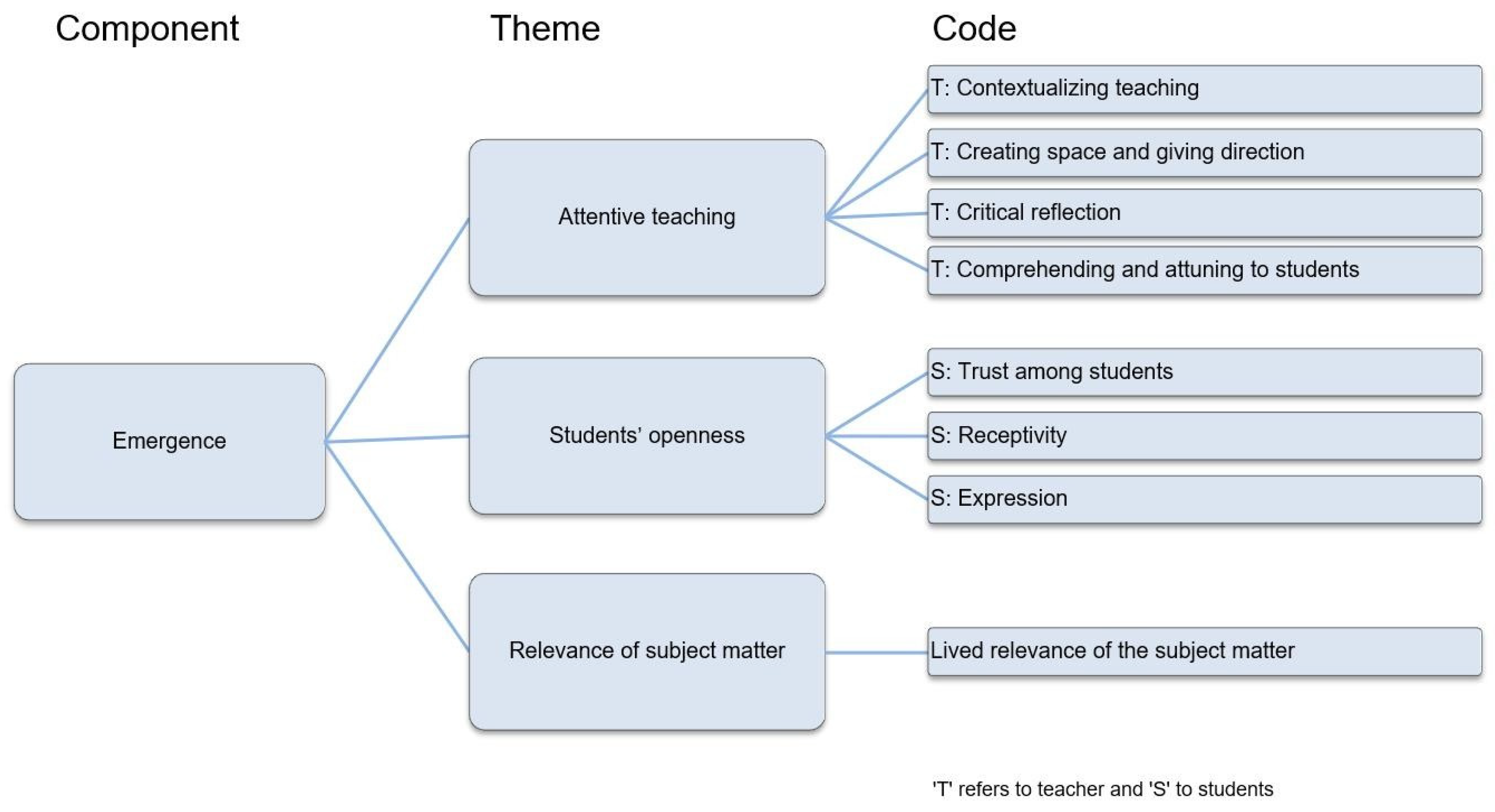

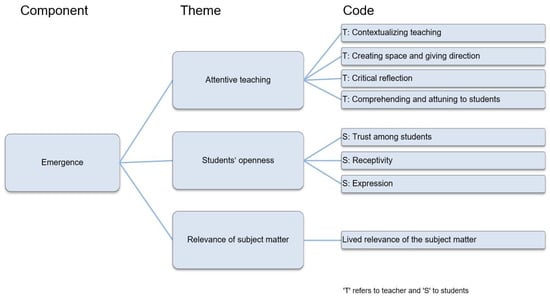

The participants’ experiences of the emergence of presence were analyzed for three themes and various codes within them (see Figure 1). The results of this analysis are described below, and illustrated with extracts from three lived experiences in which presence emerged. In this way, the various ways in which the codes were interrelated within and between the themes are revealed (quotes have been translated from Dutch and we use pseudonyms to refer to participants).

Figure 1.

Participants’ experiences of the emergence of presence.

In their accounts of the emergence of presence, all participants focused primarily on their role in enabling students’ presence by what we label “Attentive teaching”. Students’ contributions, on the other hand, were often a source of inspiration for the participants. Presence emerged in the interplay of attentive teaching, student openness, and lived relevance of the subject matter. The description by David (chemistry teacher) of his experience is an example of this.

4.1.1. David’s Experience

David described an experience in which a structured assignment on ‘green’ chemistry for students was the starting point for the emergence of presence.

| Line. | Extract | Code |

| 1. | I’ve designed an assignment so the students themselves check—in steps—how | T: Contextualizing |

| 2. | efficient, and therefore environmentally friendly, uses of atoms are. | teaching |

| 3. | I know their hobbies, I have a pretty good idea of what interests them and I referred | T: Comprehending |

| 4. | to this to let them know that I saw them. (…) | and attuning to |

| 5. | students | |

| 6. | In small groups, they developed and substantiated their own recommendation for | T: Creating space |

| 7. | the greenest method. | and giving direction |

| 8. | And then they saw: the earth is in danger….and something can be done about it | Lived relevance of |

| 9. | with this method. And then they really saw the light | the subject matter |

| 10. | And were more open. (…) | S: Receptivity |

| 11. | I joined each of the groups to get the conversation going. And then I noticed: | |

| 12. | Students contributed their own interpretations and reasoning and through the | S: Expression |

| 13. | interaction something new developed that enriched it; they contributed to presence. | |

| 14. | Without their contribution, I could not be present at all. | |

| 15. | I often asked questions to prompt them to think more critically, but I was careful | T: Creating space |

| 16. | not to reveal what was right or what was wrong. And when they asked me questions, | and giving direction |

| 17. | I preferred passing them on to other students or I would give them a small hint so | |

| 18. | they would explore together and dare to say something, even if they weren’t sure | |

| 19. | about their answer. (…) In this environment presence can come about. |

4.1.2. Interpretation

David’s idea for the assignment on green chemistry originated in a search for connections between the subject matter and current events, the daily living environment, or recognizable phenomena in the world. David knew that many students are concerned about the consequences of climate change; with this assignment he wanted to respond to their concerns. “Contextualizing teaching” in lesson designs adapted to a particular group of students at a particular moment in time was a trigger for students’ interest, in his view. For David, “Comprehending and attuning to students” as learners and persons was fundamental for this adaptation (Line 3–4). During the interview, he regularly referred to his formal and informal conversations with students and to his interest in their experiences and world views. Among a majority of the participants, the interplay of contextualizing teaching and comprehending students was considered crucial for the emergence of students’ presence. If students could give meaning to the subject matter in relation to their personal lives or the world in a broader sense, if classroom activities opened up possibilities for exceeding their own limits or developing certain skills, and if they felt seen and acknowledged, their “Receptivity” to new knowledge, insights, and learning activities was aroused, in the participants’ view.

The extract from David’s interview shows that he stressed his role in stimulating “Lived relevance of the subject matter” (Line 1–9). This lived relevance was a topic in almost every interview. However, several participants mentioned difficulties in making the content relevant, for two reasons. First, contextualizing teaching by adaptation to that group at that moment in time required an ongoing exploration of the current events and developments surrounding their subject and thorough lesson preparation. Many participants referred to time constraints. Second, some topics or subjects—such as mathematics and languages—were less rich in context for them or more difficult to connect to. Therefore, they found it more difficult to show the students the relevance of this content.

In addition, the extract from David’s interview is an example of participants’ lived experiences of presence in which students were given space. Space for students to analyze, find solutions, make mistakes, discuss, act, and respond to each other, for example, was mentioned repeatedly by all participants as conducive to stimulating students to engage actively and to make their own connections with the subject matter. However, all wished to balance “Creating space and giving direction” in order to increase the depth of the discussion, to enhance certain learning activities, to confront students, or to adjust to students’ educational needs. The extract from David’s interview details the way in which he created space while also giving direction to the subgroups (Line 15–19). With his questions, he wished to encourage participation and critical thinking. At the same time, he was reluctant to give too much direction, in order to provide space for students’ exploration. The main issue here is that he wanted to stimulate students’ “Expression” and interaction among them. Their thoughts and ideas were also an important source of inspiration for him (Line 11–14). In his experience, presence could emerge in the interplay between attentive teaching and students’ openness (Line 19).

The extent to which students were given space in the participants’ lived experiences of presence varied. As in many experiences, David created space within a well-prepared structure, whereas in some other experiences, the teacher offered plenty of space. The latter is illustrated in the next extract, from Charlotte’s interview.

4.1.3. Charlotte’s Experience

Charlotte (history and geography teacher) described the emergence of presence following her introduction of the Industrial Revolution to students in history class by means of a sequence of questions.

| Line. | Extract | Code |

| 20. | I asked: ‘What would change in your life if there was no electricity, first for one | T: Contextualizing |

| 21. | day…, then for one week…, one month….and one year? I saw them all busily | teaching |

| 22. | writing. And after each new question it looked like they were getting more into it | |

| 23. | and I saw them writing even more. | |

| 24. | Then I talked to them about it and noticed that they could really visualize it. | |

| 25. | Many of the students wanted to say something and it turned into a class discussion. | S: Expression |

| 26. | And when one student said something about food shortages, I saw that the rest of | |

| 27. | them were all ears. They considered the consequences together. (…) Then, they came | Lived relevance of |

| 28. | up with subjects such as ‘anarchy’ and ‘solidarity’ and really started debating. (…) | the subject matter |

| 29. | I only posed the occasional question to add some depth. This led to something other | T: Creating space |

| 30. | than what I had thought up, but I saw roles developing, they followed their interests | and giving direction |

| 31. | and started to see how history is part of their lives. I thought that was more | |

| 32. | important than the facts they have to learn and I was really enjoying it. I realized I | |

| 33. | had to give up being controlling. I had to restrain myself. (…) | T: Critical reflection |

| 34. | This type of lesson doesn’t always work. There are classes where there is little trust | S: Trust among |

| 35. | and no one dares say what they really think. | students |

4.1.4. Interpretation

Charlotte induced students to connect the subject matter to their own lives by visualizing (“Contextualizing teaching”; Line 20–22). Like David, she noticed this contextualization gripped their attention. The interaction among students is noteworthy in the extract from Charlotte’s interview: one student’s contribution stimulated the others (Line 26–27). They reacted spontaneously to fellow students and together they gave direction to what was talked about and gained insight in the “Lived relevance of the subject matter” (Line 27–28). Many participants explained how students became engaged by fellow students’ “Expressions”.

The extract demonstrates how the discussion among students developed as a consequence of Charlotte’s “Critical reflection”. She reflected on the value of the conversation among students, noticed her tendency to direct it, and was able to stop herself from ‘controlling’ (Line 29–33). As a result, she held back and only occasionally posed a question to bring more depth into the conversation (“Creating space and giving direction”; Line 29). In their stories of presence, participants quite regularly referred to such moments of critical reflection without automatically following a personal tendency or routine—and searching for a balance between creating space and giving direction.

Lively and spontaneous interaction with and among pupils was one of the characteristics of the manifestation of presence. However, Charlotte and many others found it was not always easy to pave the way for such interaction. They referred to the complexity of the dynamics between themselves and students and among students, in which many factors played a role. However, “Trust among students” was conceived to be an important precondition for students’ openness and therefore for presence (Line 34–35).

The next extract illustrates how the complexity of social interaction may also contribute to the emergence of presence.

4.1.5. Anne’s Experience

Anne (French teacher) told us about an experience of presence that started from the apology she made after becoming too annoyed in class.

| Line. | Extract | Code |

| 36. | One first-year student exasperated me so much I slammed his desk. (…) | |

| 37. | The entire class went quiet. I felt really awkward and immediately realized I | |

| 38. | shouldn’t have allowed myself to go that far. | T: Critical reflection |

| 39. | If a teacher gets really angry it can be intimidating for the students. | T: Comprehending and |

| 40. | attuning to students | |

| 41. | At first I tried to go on with the lesson, but that was impossible, of course. | |

| 42. | Then I stopped the class. I said I was sorry, that I shouldn’t have done it and | T: Creating space and |

| 43. | shouldn’t have let myself get carried away. Then I waited (…) At that | giving direction |

| 44. | moment I could feel that the students were relieved. A conversation started | S: Expression |

| 45. | about getting angry; it was actually pretty special. (…) But I could see that | |

| 46. | the student was still feeling uncomfortable. I talked to him after class. I | |

| 47. | thought: this isn’t good. If I let him go now (…) we’ll never fix it. At first he | |

| 48. | was irritated because I kept at it. I made it clear to him that I wanted us to | T: Creating space and |

| 49. | remain on good terms and that I wanted to listen to him. It was a good talk in | giving direction |

| 50. | the end; he said more, told me more about himself (…) A few weeks later he | S: Expression |

| 51. | came up to me and said: ‘It wasn’t easy, but it’s a good thing we had that talk. |

4.1.6. Interpretation

The extract from Anne’s interview demonstrates a different interplay between aspects of attentive teaching and students’ openness. Anne explained that her annoyance left a deep impression on everyone. The very fact that she apologized and waited—first in class and later individually—enabled presence, in Anne’s view. Participants recognized many examples in which “Creating space and giving direction” in a confrontation or the discussion of delicate issues was the cause of presence. They conceived of “Critical reflection” as a prerequisite. Similar to Charlotte’s experience, this seemed to be an impetus for self-awareness and awareness of what they considered important in that moment. This is illustrated in the extract from Anne’s interview. Through critical reflection, she was able to go beyond her first emotional reaction; she realized the impact of her behavior on students and the importance of restoring the relationship (“Comprehending and attuning to students”; Line 39). In addition, she realized that she wished to understand the background of the student’s behavior (Line 49). In this situation, a valuable exchange unfolded in class, as well as in an individual conversation where the student was able to tell his story (“Expression”; Line 44–45, 49–50). For Anne, this conversation was complex and an experience of presence for both the student and herself. It is worthy of note that in every lived experience of presence in a difficult or sensitive situation, participants explained their conscious choice to pay attention to it. They wished to acknowledge their students’ experiences and saw opportunities for students’ development embedded in the situation. Many indicated that it might have been easier to avoid the conflict or painful situation. According to the participants, creating space for such situations contributed to the emergence of students’ presence because it touched them: often these were meaningful, personal, and exciting topics.

Even though participants conceived of attentive teaching as a strong impetus for the emergence of presence, it was no guarantee of success. For all, presence could be neither predicted nor controlled. A well-prepared lesson and their own enthusiasm could lead to nothing but students watching indifferently, or presence could start unexpectedly from a student’s contribution. Students’ openness and the lived relevance of the subject matter were considered important factors as well, which were perceived as partially outside the control or influence of the teacher. The extent to which participants experienced success or difficulties in the emergence of students’ presence varied. A few participants experienced a more subtle, continual presence of students and themselves in their classes, whereas others referred to clear, isolated situations.

Participants also referred to personal circumstances or traits as a hindrance for the emergence of presence for themselves. For example, they pointed to a heavy workload or stress that kept them occupied, or to losing touch with their own needs or limits. Many mentioned tensions in relation to external demands and a focus on raising test scores. Charlotte explained: “There are also lessons, a test or exam coming up, then the material just has to be covered and I’m less focused on the students and on what I think is important.” Regular and straight conversations with colleagues about teaching experiences were mentioned by some participants as an incentive for seeking to be present themselves.

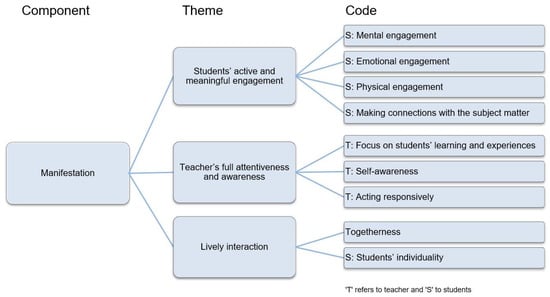

4.2. The Manifestation of Presence

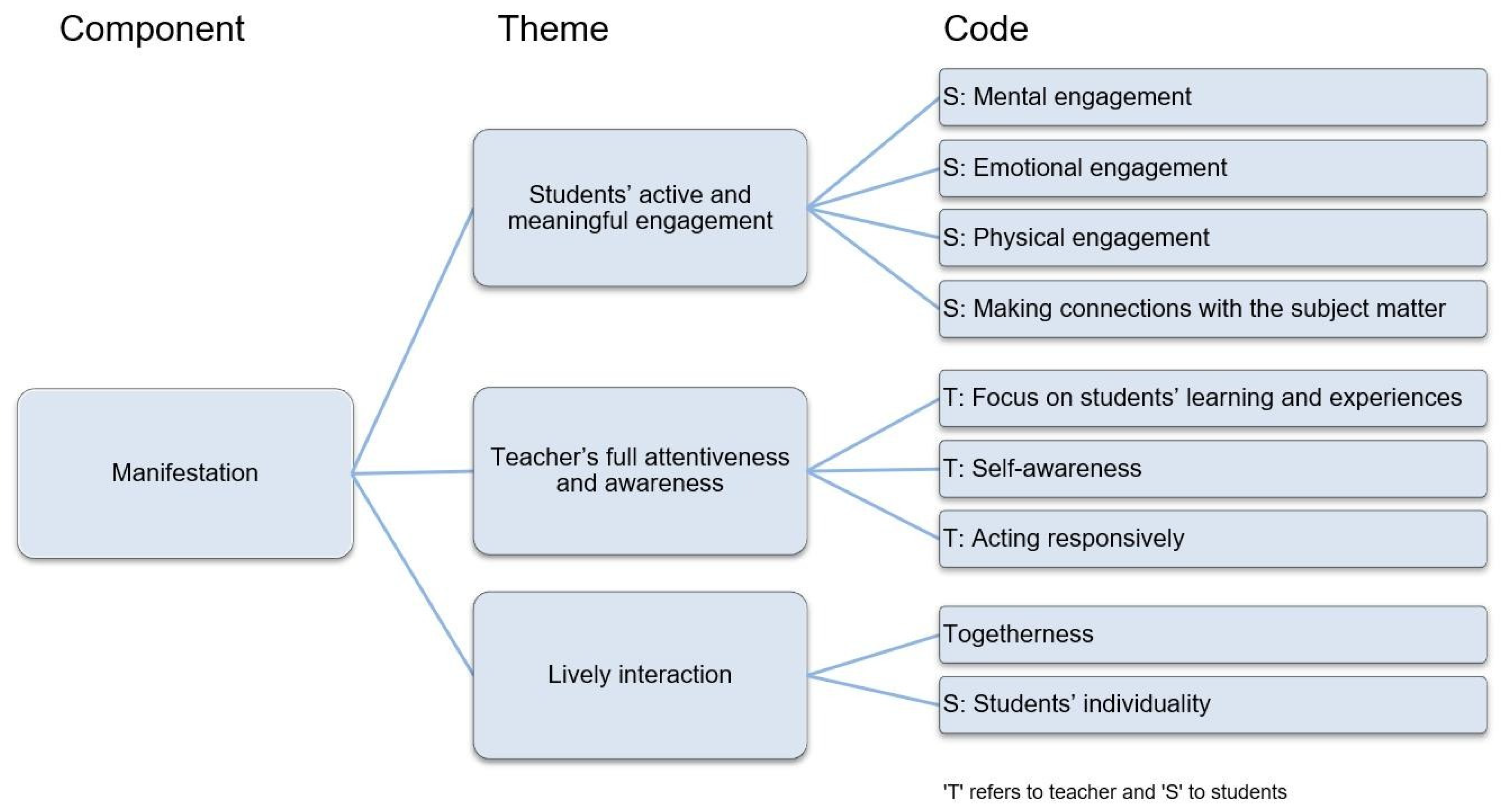

In analyzing participants’ experiences of the manifestation of presence, we found three themes and various codes within them (see Figure 2). Again, extracts of three lived experiences in which presence became manifest are presented in order to illustrate the various ways in which the codes were interrelated within and between the themes.

Figure 2.

Participants’ experiences of the manifestation of presence.

In their accounts of the manifestation of presence, participants emphasized ‘students’ active and meaningful engagement’ and ‘lively interaction’. What happened in an experience of presence was not pre-planned, but grew out of the here-and-now situation in the classroom and developed from the participants’ acting responsively, which they felt they were able to do through their focus on students’ learning and experiences and their self-awareness. This is what we labeled as “Teachers’ full attentiveness and awareness”. Angela’s experience is an example of this.

4.2.1. Angela’s Experience

Angela (German teacher) described a sequence of events in which students were actively engaged in an assignment about the passive voice. In turn, one student got a sentence on a note, for example: “The chicken is beheaded,” and drew this on the whiteboard. Others guessed the meaning in groups and had to formulate a good sentence in the passive voice to express the meaning.

| Line. | Extract | Code |

| 52. | (...) the student was thinking of something and it appeared on the whiteboard via | |

| 53. | his hand, and that’s a slow process, of course (...) there was silence, the whole class | |

| 54. | was watching his hand and thinking. And I saw: some of them already had an | S: Mental |

| 55. | idea and were leafing through their books, searching for the right wording, eager; | engagement |

| 56. | but most of them were watching closely, very attentive. | |

| 57. | And then the student drew a single line and they all immediately understood. | |

| 58. | And I saw everyone move, call to each other, leaf through the books, and it was | S: Physical |

| 59. | really loud, | engagement |

| 60. | full of enthusiasm, | S: Emotional |

| 61. | engagement | |

| 62. | having fun working together and wanting to learn (…) | Togetherness |

| 63. | I was watching everything very closely. The person I let draw and the sentence I | T: Focus on |

| 64. | gave him had to do with what I could see: does everyone understand it? How | students’ learning |

| 65. | secure or insecure does a student seem, is he or she still interested? | and experiences |

| 66. | I adjusted my instruction accordingly. (...) | T: Acting |

| 67. | Then I asked a student who often looks quietly and absently out the window to | responsively |

| 68. | draw. And he could draw really well. | |

| 69. | It was the first time the group had seen that boy create something. They discovered | S: Students’ |

| 70. | something new about him and they were really fascinated. | individuality |

| 71. | I enjoyed that; it was so nice seeing it happen to him. | T: Self-awareness |

| 72. | Then I asked him to draw even more complicated things, such as: ‘The child is | T: Acting |

| 73. | being born’ (...) He did it amazingly and his classmates let him know it | responsively |

4.2.2. Interpretation

The extract from Angela’s experience demonstrates the emphasis she placed on students’ presence as being actively engaged. Angela referred to their attitude when being present as ‘eager’, ‘watching closely’, and ‘very attentive’ (Line 55–56). Others spoke of students’ presence as ‘awake’ or ‘alert’. Angela indicated students’ ‘thinking’, their ‘enthusiasm’ and described their non-verbal behavior (Line 54–60), which we respectively referred to as “Mental, Emotional and Physical engagement”. Many participants highlighted this broad nature of students’ active engagement as a manifestation of students’ presence.

In addition, Angela did not just mention students’ individual experiences; she referred as well to the shared experiences of pleasure and eagerness in this teaching situation (Line 62). This atmosphere of “Togetherness” in classroom or peer interaction was an important indication of presence for all participants.

Being present herself, Angela based her choices (“Acting responsively”) on what she noted in how every student dealt with the subject matter, as well as on how they felt (“Focus on students’ learning and experiences”; Line 63–67). At one point, it turned out that a student was very good at drawing. Angela sensed the impact on the group: the students became fascinated by a fellow student they did not notice normally. She referred to her own feelings of enjoyment as well. Relying on this intuitive understanding and her own feelings, she made the practical decision to let the student draw even more and more difficult sentences (Line 72–73). In several experiences of presence, it seemed that being attentive and aware of students and being self-aware supported participants in gaining a nuanced understanding of the students and the situation and acting responsively upon it. This mainly concerned the subtle events in the interaction between teacher, students, and subject matter, or among the students.

The interplay of having a “Focus on students’ learning and experiences”, “Self-awareness”, and “Acting responsively” was a prominent part of every experience of presence. Lucas’s lived experience of presence illustrates variations of this interplay.

4.2.3. Lucas’s Experience

In instruction about the topic ‘rich and poor’, Lucas (geography teacher) visualized a situation of poverty, and then a conversation unfolded:

| Line. | Extract | Code |

| 74. | I told the class about a trip I once made and I was completely engrossed in my | |

| 75. | story. At that moment I wanted to make the subject matter more relevant to | T: Self-awareness |

| 76. | students, to enliven it in order to stimulate them to think more deeply about | |

| 77. | poverty. The students were listening with bated breath and all eyes were on me. | S: Physical |

| 78. | engagement | |

| 79. | That gave me a boost. At that moment it felt right, that it was sincere [...] | T: Self-awareness |

| 80. | Then, I noticed it touched them, some of them were really sad. I was too, that’s | S: Emotional |

| 81. | also vulnerable … | engagement |

| 82. | as if the experience was all of ours […] | Togetherness |

| 83. | And then some students started asking questions, and these were questions that | |

| 84. | adults have too, about justice, causes and solutions; issues that really concern | S: Students’ |

| 85. | them. | individuality |

| 86. | And because they felt it, and thought things through, their questions were | S: Making |

| 87. | deeper. One student asked about my personal trip experience. Another asked | connections with |

| 88. | about debt and solving problems. | the subject matter |

| 89. | Their interests and their way of thinking came to the fore. | S: Students’ |

| 90. | The students began discussing it with me and with each other. I posed many | individuality |

| 91. | questions, so different students could speak […] | |

| 92. | We were completely together,discovering what it means to be poor. […] | Togetherness |

| 93. | I was only concentrating on the conversation, intensely: What does he think, what | T: Focus on |

| 94. | does she think? What are their opinions and how can I show them the differences | students’ learning |

| 95. | between them? | and experiences |

4.2.4. Interpretation

In the first part of the experience, Lucas is speaking, introducing the subject matter with a personal story. Here, Lucas’s presence manifested itself in being completely involved in his story, while being connected to what he personally desired to achieve (Line 74–77). In this variation of “Self-awareness”, it seems that he acknowledged and trusted himself and the actions that were an expression of that self. Simultaneously, students’ presence became visible to him by their ‘bated breath’, focused gaze (“Physical engagement”; Line 77), and “Emotional engagement” (Line 80). It is noteworthy that Lucas himself enjoyed the students’ attention (“Self-awareness”; Line 79). In his view, he and the students shared a sense of sadness about the story (Line 82). This wordless “Togetherness” was part of several of participants’ experiences of presence.

In the second part of the extract, Lucas talked about the classroom interaction. Many lived experiences of presence took place in interactions between teacher–students or peers, and the features of these interactions seemed lively. Lucas emphasized a shared focus on the subject matter and a focus on each other (Line 91–92). This demonstrates a variation on “Togetherness”, namely one with words and enjoying exploring the subject matter together. For many participants, when students were genuine participants, listened to and able to build upon others’ questions and ideas, this was a sign of presence for them. In Lucas’s experience, students participated with their profound questions, interests, and thoughts (“Students’ individuality”; Line 83–85) and he related this to their “Emotional and mental engagement” (Line 86). Many participants had a strong sense that because of students’ active engagement—with head, heart, and hands—their questions and understandings were more profound, and students were stimulated to make their own “Connections with the subject matter”. For the participants, the very fact that students placed the subject matter in a larger context was a sign of their presence.

In Lucas’s example, there was a high level of teacher guidance. Lucas’s presence was manifest in being focused on the content of the conversation and on students’ learning and in responding by asking questions and confronting them with different viewpoints (Line 93–95). When students mainly explored the subject matter themselves, presence was manifest in a different way. Jesse’s experience is an example of this.

4.2.5. Jesse’s Experience

Jesse (mathematics teacher) explained how groups of students had to solve mathematical problems in order to reach a higher level in a game.

| Line. | Extract | Code |

| 96. | They were 100% busy: explaining to each other, building on each other’s thoughts | Togetherness |

| 97. | pointing things out; | |

| 98. | I saw all those heads leaning in towards each other. I saw them all nodding, | S: Physical |

| 99. | engagement | |

| 100. | coming back with something they had learned earlier, | S: Mental |

| 101. | engagement | |

| 102. | their own connections, new questions. | S: Making |

| 103. | connections with | |

| 104. | the subject matter | |

| 105. | They really wanted to work it out, were very enthusiastic, all of them. […] | S: Emotional |

| 106. | engagement | |

| 107. | I continued to watch the way they were working, to see whether everyone could | T: Focus on |

| 108. | follow and was feeling secure enough. There was this one group, | students’ learning |

| 109. | and experiences | |

| 110. | I got a bit impatient watching them: | T: Self-awareness |

| 111. | no one was writing anything, they weren’t conferring with each other. At first, I | T: Focus on |

| 112. | waited and listened to see if they were making any progress. It was of course possible | students’ learning |

| 113. | that they needed more time to get going, so there was no need to intervene yet. But | and experiences |

| 114. | they just weren’t getting anywhere. | |

| 115. | I spoke with them for a couple of minutes because it didn’t click. Together, we found | T: Acting |

| 116. | some solutions for how they could work together better. (…) | responsively |

| 117. | Students also came to me with questions and solutions. And we laughed at each | Togetherness |

| 118. | other, with each other. I didn’t have to stop anymore to get their attention, or have | T: Acting |

| 119. | eyes in the back of my head. I was able to approach the conversations more freely | responsively |

4.2.6. Interpretation

The extract from Jesse’s interview shows a high level of student autonomy in peer interaction. Students’ presence became manifest to him in their enthusiasm and their abstract thinking in terms of making connections with prior knowledge (“Mental engagement”; Line 100). Jesse described how the students intensely conferred with each other (“Togetherness”; Line 96-97), by which they developed their understanding, solutions, or new questions (Line 102). He observed them from a distance and was focused on their thinking, cooperation and whether they seemed to feel confident (“Focus on students’ learning and experiences”; Line 107–108). What he noticed and considered seems deliberate and conscious (Line 110–114). This illustrates a variation on the experiences of Angela and Lucas, in which they referred to an intuitive engagement in this process of being attentive and aware. This exemplifies the variation our analysis revealed. In some experiences of presence, participants pointed predominantly to observations, considerations, and choices, whereas in others they mainly referred to feelings and responses.

In addition, Jesse typically seemed to relate his own presence to students being present (Line 117–119). Most participants argued that if students were actively engaged, they, as teachers, could focus fully on students’ learning, experiences, and their meaningful connections to the subject matter. If not, as Jesse explained, their attention was more dispersed and also aimed at maintaining order and discipline.

The theme “Teacher’s full attentiveness and awareness” outlines participants’ understandings of their own presence as concurrently being attentive to and aware of students and being aware of themselves. However, this self-awareness was experienced as less self-evident than their awareness of students. Participants more often mentioned their struggle: they pointed to their natural tendency to be focused on students and that they tended to forget themselves. Some of them referred to the fatigue or emotional impact this could entail. When they simultaneously experienced a sense of connection with their own feelings, bodily experiences, thoughts or aims, this was felt as trust, self-confidence, and vitality. It seemed that being attentive to and aware of students as well as themselves supported participants’ ability to discriminate in the moment between what was important and not, while at the same time guarding their limits.

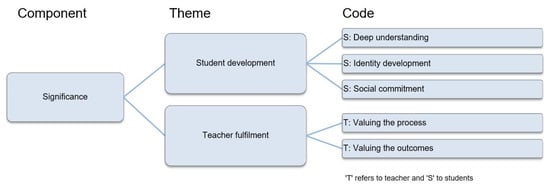

4.3. The Significance of Presence

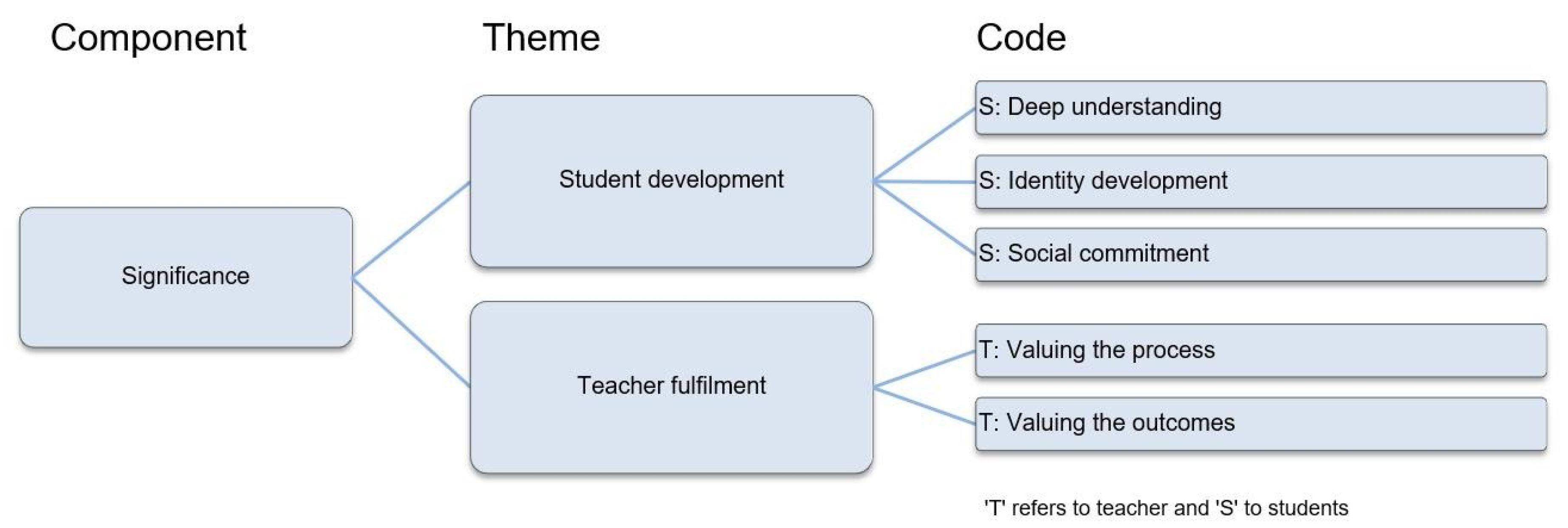

In our analysis, we distinguished between the significance the participants attached to presence for the students and for themselves as teachers, which resulted in one theme for each (see Figure 3). The significance participants attached to presence was not so much related to particular lived experiences of presence, but more to how they experienced presence in class in general. For this reason, these results are not illustrated with extracts from lived experiences, but with quotes that demonstrate the overarching significance participants attached to presence.

Figure 3.

The Significance participants attached to presence.

4.3.1. Student Development

This theme concerns the participants’ notions of how presence can contribute to students’ development. With regard to academic learning, most participants argued that presence stimulates students to familiarize themselves with the subject matter, which may increase their deep understanding. Robert (physics teacher) told us:

If they go one step deeper than just memorizing, if they have really thought it through and put it into practice, then maybe the subject matter establishes itself better, also in how they experience it.

They typically assumed that students’ personal development was the most important significance of presence. However, the interpretation they gave to personal development varied. Some emphasized that students can learn to know, trust, and develop themselves, due to their active meaning-making processes and unfolding individuality when being present, as indicated by Bram (history teacher):

Ultimately, presence gives the students room to experience who they are themselves, and what parents and teachers do, including me, we provide students with frameworks and value systems. […] If students are present, they experience more quickly, maybe more consciously, how it is for them.

Others emphasized the significance of presence for the development of students’ social commitment, because students were present in learning to cooperate or in learning to respect each other’s differences, as illustrated by this quote from Jannah (biology teacher):

Through such experiences the students change something in their opinion of a classmate, and maybe they think like: “Okay, next time I shouldn’t be so quick to judge.” Those are really small things, but naturally, if you often learn small things, that makes a difference that contributes.

4.3.2. Teacher Fulfillment

For the participants themselves, presence contributed considerably to their fulfillment. They referred to feelings of pleasure, energy, and to a deep sense of fulfillment. On the one hand, all attached an intrinsic value to the process when students and they themselves were present, and on the other hand, they valued the outcomes of the process. Both values are illustrated in this quote from Simon (mathematics teacher):

If you and the students are busy looking at the material together and it’s really enjoyable for them to do that, then you’re engaged in a pleasant work process. Those sorts of experiences, that’s why I do it. I enjoy it, when I see students learn something from my subject, but even more so in how they are human.

Participants often justified the significance they attached to presence by a reference to a particular personal value or belief. They felt that this value or belief was reflected in some way in their experiences of presence. Even though participants referred to different personal values and beliefs, their commitment to students’ personal development and future citizenship was very similar. The experience of being able to contribute to this development by means of the subject matter and by means of interaction with students was prominent in all participants’ reflections on the significance of presence.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

In this study, we aimed to gain insight into teachers’ experiences of the emergence and manifestation of presence in their daily educational practice and into the significance they attach to presence. All participants recognized presence in their daily practice and could bring forward ample lived experiences of presence. We found that presence could not be predicted or controlled, in participants’ views. Presence actually emerged from the interactional process between attentive teaching, openness of students, and lived relevance of the subject matter. Yet participants had the experience that they could create a breeding ground for presence by actively searching for and paying attention to the relevance of the subject matter for particular students in a particular situation. The participants placed students at the heart of their experiences of the manifestation of presence. Students’ meaningful engagement as whole persons with the subject matter was a crucial sign of presence for them. Their own presence was mainly and naturally experienced as an in-the-moment attentiveness to and awareness of students’ learning and experiences. While their self-awareness was less naturally experienced and involved tensions as well, it was experienced as important for full-fledged presence and for acting responsively. It is noteworthy that many lived experiences of presence occurred in interactive situations. Here, presence became manifest in experiencing togetherness and in students’ individuality that became visible for the participants. The significance participants attached to presence pertained to its contribution to students’ deep understanding of the subject matter as well as to their personal development, by means of students’ active meaning-making processes and by means of the lively classroom or peer interaction. For the participants themselves, this sparked feelings of fulfillment in varying degrees.

Our analysis also revealed variations in teachers’ experiences of presence. Most salient were variations in the emphasis on conscious—though not elaborate—attentiveness and perceptiveness on the one hand, and an intuitive character of attentiveness and awareness on the other hand. The first variation seemed to occur when teachers had or took time for some degree of detachment from the classroom situation, and the second when they were completely absorbed in the onward flow of events in classroom practice. These variations may be associated with the nature of the classroom situation, with personal characteristics, and/or with participants’ values and beliefs about teaching. We found only one variation in teachers’ experiences of presence that might be associated with the difference in teaching subjects. Some of the mathematics and language teachers mentioned difficulties in contextualizing the instruction. They felt this may have constrained the emergence of presence in their classes.

Participants’ understandings of their own presence had much resemblance to the three dimensions of connection in ‘presence in teaching’ [17]. Concerning the connection to self, our findings seem to confirm that presence calls on the entire being of the teacher, mentally, emotionally, and physically [1,2,19]. Furthermore, the regular references of our participants to their pedagogical values and beliefs reveal the moral character of presence: they wanted to contribute to students’ development [17]. With respect to the relational connection, presence was experienced as an attentiveness to and comprehension of the whole student, not merely as a learner [5,6,15,17]. Teachers’ experiences of the interaction and intersubjectivity between teacher, students, and subject matter—by which new understandings and meanings emerged—are consistent with the pedagogical connection [17,25].

Rodgers and Raider-Roth’s [17] conceptualization does not contain an elaboration on the coherence between these three dimensions. Our findings indicate that the participating teachers, by being concurrently attentive and aware of students and of themselves, gained an in-depth and nuanced understanding of and sensibility to what was happening in class. This understanding and sensibility allowed them to judge what they considered best in that moment for the students and their development. In this way, our results specify what Rodgers and Raider-Roth called the “moral imperative of self” [17] (p. 273). Moreover, our findings reveal that the moral scope of presence seems to transcend the teachers’ connection to self, which was also expressed in how the participants sensed, understood, judged, and acted in trying to do good when they were present. This implies that, in our view, the second and third dimensions of presence in teaching are not merely relational and pedagogical by nature, but also moral. What is more, by the distinction we made between the three components of emergence, manifestation, and significance, and by incorporating students’ presence, our study has brought forth new and refined insights into presence in daily educational practice. First, the distinction sheds light on the differentiation between ‘doing presence’ and ‘being present’. Teachers’ experiences of the emergence of presence bring to the fore how the participants intentionally and deliberately were paying attention to or, in other words, were making connections with self, students, and the subject matter. On the other hand, teachers’ experiences of the manifestation of presence reveal how they ‘found themselves’ to be attentive to and aware of or, in other words, how they were connected to self, students, and the subject matter. Second, participants experienced presence of themselves and of students as being strongly related in a reciprocal way. Hence, not simply the teacher, but also the students seem to be crucial to the emergence and manifestation of presence. Third, our study revealed that presence does not emerge automatically or coincidentally. On the contrary, teachers’ lesson preparation, their comprehension of students, and the relevance of the subject matter were experienced as important for creating a context in which presence could emerge. Finally, this study has given insight into students’ individual and shared active and meaningful engagement as a necessary condition for the significance that participants attached to presence for the quality of students’ experiences and for their academic learning and personal development.

The distinction between the three components of presence is an analytical one, not a chronological one. They regularly occurred simultaneously. Hence, the components each highlight a different analytical aspect of presence: what it requires, what it is, and what it means.

Relevance of the Study and Future Research

Despite the exploratory character of our study and the small sample size, we think that our study can contribute to the further refinement and development of the conceptualization of presence in education. We used a purposive sample of rather reflective teachers with an affinity for presence and realize that presence may be experienced differently by students and by other teachers.

Future research can build on the distinction between emergence, manifestation, and significance. First, it can aim at gaining a deep understanding of students’ experiences of presence. Second, a combination of qualitative and quantitative follow-up research among students and teachers that focuses on validating the recognition of themes in relation to experiences of presence may contribute to an empirical substantiation of the emergence, manifestation, and significance of presence in education.

We found that participants positioned presence in a professional orientation that goes beyond standardized teaching and preparing students for predefined outcomes. Participants’ in-the-moment full attentiveness and awareness contributed to their in-depth and nuanced understandings of and sensibility to what was happening in class and to their apprehending of students’ learning and experiences. Our participants felt that this understanding and apprehending enhanced their ability to see or sense the meaning of a classroom situation and the possibilities for students’ development within it, to discern what was important or not, to judge, to choose, and to respond. We believe our findings contribute to insights into teachers’ reflection-in-action, which is widely recognized “as a significant competence for teachers (…) to optimize their teaching behaviors on the spot” [42,43] (p. 1). Mintz [44] argued that, at present, we have only limited understanding of how teachers’ knowledge used in the process of reflection-in-action arises in the intersubjective relationship between teacher and students. We add to this by specifying how teachers’ reflections can emerge from being fully attentive and aware during the interaction between themselves, the students, and the subject matter. This study offers detailed accounts of what ‘goes on in the moment’ within this process of teachers’ coming-to-know.