Abstract

In this paper, I focus on the process of building a dissertation that honored the Black souls of my undergraduate participants along with my own Black soul as a form of resistance to advance racial equity in higher education. Through endarkened narrative inquiry, this paper will address the internal tensions I navigated in building a dissertation that centered Blackness through the prism of what I have conceptualized as Black Finesse. I unveil components from my dissertation that manifested a shift in how knowledge generation can be developed and written. I conceptualized a methodology entitled race-grounded phenomenology (RGP) and call for a re-imagining of qualitative research around the ways Black students navigate higher education. I reflected upon the internal tensions and mental leaps of my dissertation process through theoretical decolonial inquiry. As decolonial praxis to unmake the canon of research and dissertation creation, I lean upon four elements of decolonizing higher education as a way to reimagine decolonial futures that were actualized via my dissertation process.

1. Introduction

As a recent PhD, I remember grappling with how I could use my dissertation as an anchor to not only advance equity in higher education, but to decolonize the ways in which dissertation research is developed, written, and revealed. Research on advancing equity in higher education must include perspectives of the internal tensions of the dissertation process from the lived experiences and stories of Black scholars. The internal tensions of the dissertation processes of Black scholars can unveil the efficacy of scholars to play a role in decolonizing research. Furthermore, the unveiling of the internal tensions of the dissertation process reflects that socialization of scholars on the part of higher education institutions as well and indicates the institutional positioning of and reckoning with decolonization. I desire for this written work to connect with Black scholars and scholars of color who are on their dissertation journey and grappling with ways to decolonize their research while positioning themselves within their research. Furthermore, I aspire for dissertation committee members, faculty who teach methods courses, and research processes courses to connect with this work as a way to bridge theory into praxis toward decolonizing dissertation research.

The higher education context produces racialized experiences for Black students and students of color [1,2] which calls for an unveiling of those experiences to decolonize the ways we as scholars engage with notions of diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. Internal tensions of Black scholars inform the manifestation of whether or not higher education institutions are in fact moving toward transforming racial equity within academia. I am a Black race scholar activist who attended a traditionally white institution with a committee inclusive of an Indigenous woman, a Black man, and a Mexican American woman, and I still struggled to center Blackness in my dissertation because of digesting the consequential toxins that float from rhetoric of diversity, equity, and inclusion. I wondered if my desire to center Black undergraduate students and my own Black experience would be considered dismissive of students of color and/or deemed not inclusive. I had to wrestle with not doing a comparative study that considered the experiences of Black undergraduate students in nexus with white students. Much of my own internal wrestling is reflective of the experiences of Black doctoral students in higher education. Within higher education, Black students navigate, “celebrated qualitative research venues [that] overrepresent white sensibilities as a normalized benchmark for qualitative research. Within this space, culturally situated inquiry, especially from Black women’s perspectives, is less prevalent. Attempts to engage in such inquiry make Black doctoral students vulnerable to the power relations between a Black student and her institution and discipline” [3] (p. 1). Hence, as a Black race scholar activist, I felt vulnerable and navigated power dynamics as I experienced internal tensions in my mind, body, and soul to simply center Blackness which is my most salient identity. Even with race being my most salient identity, I experienced tension amidst mental leaps with centering Blackness in my dissertation research. I had to decolonize my own mind and research processes to reckon with the fact that the Black student experience should not be essentialized to the experiences of students of color or to ethnicity like being African and Black. Furthermore, the white undergraduate student experience is also not what Black undergraduate students neither deserve nor should aspire to acquire.

Through endarkened narrative inquiry [3,4], this paper serves as a walk through my navigation of mental leaps and internal tensions as a Black race scholar activist to position my work in decolonial ways of being and knowing in higher education. Furthermore, I share my endarkened narrative through the prism of what I conceptualize as Black Finesse for the purpose of re-imagining future decolonial ways of being in higher education. Revealing the mental leaps I navigated allows for the often racialized invisible labor and silences of Black female scholars to be made visible [5]. The revelation of the mental leaps Black scholars make, who have an epistemological commitment to decolonizing higher education, is necessary for the further manifestation and praxis of decolonization in higher education.

1.1. Dissertation Context by Way of Framing

I will provide the context of my dissertation for the purpose of contextualizing the mental leaps and endarkened narrative inquiry [3,4] I navigated amidst the dissertation process. My recent dissertation was an exploratory study inclusive of ten Black undergraduate students who navigate what I defined as the political science paradigm. The political science paradigm is reflective of the structures, politics, and agency exuded by political science faculty. The study answered the following research questions:

- How are Black students defining political science as a discipline?

- What are the ways in which structures, politics, and agency are embodied in political science?

- What are the ways in which Black students create structures, politics, and agency amidst political science?

Through this research, I conceptually developed a methodology entitled race-grounded phenomenology (RGP). I developed RGP to disrupt how whiteness [6,7,8] which situates race as an issue of “the Other,” and can lead to a positivist lens of understanding Black student experiences which further diffuses those experiences. Methodologically, RGP leans on catalytic validity [9] as an analytical tool to determine the value and validity of the study. RGP centers the lens of the participants as a base for knowledge generation rather than relying on normative measures of validity. The study was focused in one state and included participants from five four-year institutions of higher education. Through arts-based student interviews, or what I called rap sessions, findings revealed how Black undergraduate students exhibit flair and tenacity, or what I call Black Finesse. The following findings transpired:

Finding One A: Why Black undergraduate students chose political science as a major;

Finding One B: How Black undergraduate students defined political science;

Finding Two A: Race transcends political science;

Finding Two B: Representation of Blackness in the political science paradigm;

Finding Two C: Coping mechanisms exhibited by Black undergraduate students; amidst the political science paradigm.

There were many contributions from the study reflected from the aforementioned findings. However, I will anchor much of the following discussion on RGP that bridges an eclectic of critical theories [10] of race and led to a revelation of the ways Black students, including myself, exhibit Black Finesse, which reflects the knack, flair, and inquisitiveness Black students exhibit amidst higher education contexts and other sociopolitical contexts. While Black Finesse does not only exist in higher education spaces, I will focus much of the framing in a higher education context. Black Finesse reflects the versatile ways Black folks navigate education and sociopolitical structures on our terms to reclaim our ways of knowing and being. Black Finesse is indicative of the agency exerted by Black students that is not always for the consumption of others. Black Finesse resituates agency exhibited by Black students that may or may not be visible in higher education spaces. Black Finesse also honors the racialized invisible labor executed by Black students in higher education spaces amidst classroom dialogues and research around race. The racialized invisible labor of Black students also is indicative of the various ways in which Black students make negotiations to protect their souls and emotional labor in higher education spaces. I am choosing to take a moment to highlight my own Black Finesse by further explaining the mental leaps developed in building the race-grounded phenomenology. When I was a Black doctoral student, I exhibited Black Finesse in creating a new methodology. There is a need in qualitative research to center Black intellectual contributions to the field and as a way to further decolonize ways of knowing, being, and researching in higher education contexts. “Banks (1992), Gordon (1995), Alridge (1999, 2008), Johnson (2000), Brown (2010), and Grant, Brown, and Brown (2016) argue, critical educational thought is rarely conceptualized from the standpoint of the Black intellectual tradition” [11] (pp. 23S–24S).

1.2. The Necessary Ingredients for a Race-Grounded Phenomenology

My dissertation study conceptually walks through the necessary ingredients, or tenets to conduct a race-grounded phenomenology. The following tenets were codified to bring about a race-grounded phenomenology: eclectic of critical theories of race, self-reflexivity, self-reflexive wokeness, reciprocity, collaborative interviewing, artistic methods, and catalytic validity.

Eclectic of critical theories of race: in the case of this study, the bridged critical theories of race centered race and racism, confronted whiteness in the discipline of political science, and also honored the psychological negotiations Black undergraduate students make through identity enactments [12]. Identity enactments acknowledge the ways of being and doing within one’s racial context and outside of one’s racial context.

Self-reflexivity: Self-reflexivity requires researchers to unveil their experiences with the phenomena under study. Self-reflexivity, however, does not require the researcher to center any sort of identity salience and/or identity oriented experiences associated with the phenomena.

Self-reflexive wokeness: Self-reflexive wokeness required me to center race not only concerning my experiences with the phenomena under study, but to center race for the participant as well. “Self-reflexive wokeness shifts researchers from simply naming one’s insider/outsider status to embodying what the salience of those identities means for not only you as a researcher, but for your participants” [10] (p. 50).

Reciprocity: At the end of the rap sessions, I shared reflections to honor shared vulnerability as a form of reciprocity for the participants sharing vulnerability and to be mindful of power dynamics embedded within research contexts. Furthermore, I centered the meaning making of participants as a part of the data analyses to honor the wisdom of the participants and to mitigate power dynamics embedded within the research process. This form of reciprocity is consistent with the phenomenographic method [13] which allows participants to participate in the meaning making process of the rap sessions rather than the meaning making be solely grounded through my lens.

Collaborative interviewing: Being in dialogue with participants rather than “interviewing” reflects collaborative interviewing [14]. I called these collaborative interviews rap sessions within my study.

Artistic methods: There was an opportunity for participants to reflect on each rap session and an opportunity to illustrate or draw their experiences as a form of release from the rigidity of the written word. “Art has to be a kind of a confession...the effort it seems to me is; if you can examine and face your life, you can discover the terms with which you are connected to others, and they can discover, too, the terms with which they are connected to other people” [15] (p. 21).

Catalytic validity: In traditional research paradigms, validity is seen through notions of validity of the research in and out of itself rather than based upon the experiences of the participants. Catalytic validity is “the degree to which [a process] re-orients, focuses and energizes participants toward knowing reality in order to transform it” [9] (p. 68).

2. Materials and Methods

My epistemological stance stems from critical traditions which lead me to unveil the “why and how” [16] behind my dissertation research and the development of a new research methodology RGP. I wanted to unveil the “why and how” concerning my internal tensions and mental leaps as a Black race scholar activist while developing race-grounded phenomenology as a methodology within my dissertation research. Furthermore, as I reflected on my dissertation process, I wanted to connect my emotions, experiences, and soul from the lens of Black feminist thought for this paper. Hence, when considering what methodology to use to reflect upon my dissertation process and developing a new methodology for this paper, I chose endarkened narrative inquiry [3,4]. Endarkened narrative inquiry was developed to engender the joys, pain, soul, and intellectual play from the collection of narratives from Black women. From the collection of these Black female stories and lived experiences “three thematic tropes for endarkened narrative inquiry evidenced in Black women’s narratives: (a) life’s lessons on surviving and thriving as a woman, a Black person, and a Black woman; (b) spirituality as a protective barrier and a source of strength; and (c) lives, dreams, and hopes deferred” [4] (p. 7). I prose my internal tensions and mental leaps to share my life lessons of surviving and thriving in my dissertation process as a Black scholar activist. I prose the depths of my soul to demonstrate spiritual grounding and strength I and my participants experienced while being ridden with internal tensions, doubt, pain, and joy while navigating higher education. I prose and exude Black Finesse while simultaneously honoring the Black Finesse of my participants to further honor Black dreams and hopes.

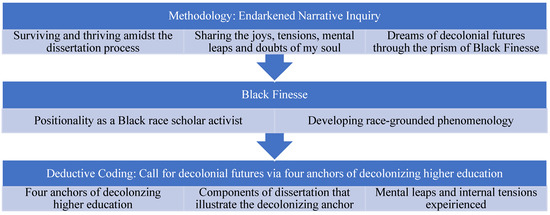

First, I will unveil my internal tensions and mental leaps of developing the methodology race-grounded phenomenology from the base of endarkened narrative inquiry [3,4]. I systematized the “why” behind developing a race-grounded phenomenology to exhibit my own version of endarkened narrative inquiry through the prism of what I call Black Finesse. I desired to further situate the “why and how” concerning my unction and calling to iterate a methodology as a Black race scholar activist. Second, I will call upon my dissertation experiences and endarkened narrative from past and present to call for decolonial futures. Tuitt and Stewart’s [17] anchors of decolonizing higher education provide implications from my endarkened narrative inquiry from my storied experiences. In order to reflect on my dissertation experiences from the past while calling for decolonial futures, I lean on four anchors named to decolonize higher education [17] as a way to systematize my internal tensions and mental leaps within the dissertation process. Particularly speaking, I used the four anchors of decolonizing research to reveal my wonderings, silences, doubts, joy, and pain that is often held close to the chest for not only me, but other Black students in higher education. The four anchors of named to call for decolonizing higher education are: “(1) decolonising the mind through ways of knowing and knowledge construction; (2) decolonising pedagogy; (3) decolonizing structures, policies and practices; and (4) reimagining the academy from a decolonised lens” [17] (p. 102). I used endarkened narrative inquiry as a methodological and theoretical foundation to share my storied racialized experiences amidst the dissertation process not only as my story, but an embodiment of the many Black stories of students in higher education. Furthermore, I use the four anchors named to decolonize higher education as a form of praxis to systematize my reflective thinking and storied experiences. I wanted to simultaneously situate my Black Finesse in the past and decolonial futures. I created a chart that depicts the ways in which I systematized my thinking (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological framing toward decolonial futures.

I anchored my contemplative reflections alongside mental leaps of building the dissertation from conception to the final product through the four aforementioned anchors of decolonizing higher education as a framework to call for decolonial futures. Because of already having the four tenets in mind, I reflected upon my dissertation experiences and mental leaps, stages of development and the final product through deductive coding. As sources of data, I utilized my dissertation and the memos I created about my dissertation process.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Unveiling the Why behind Race-Grounded Phenomenology

Positionality indicates the necessary self-reflexive work of acknowledging how my identities and experiences shape my decision-making while engaging myself and participants in research. My journey of grappling with positionality is embedded and centered in my identification as a Black race scholar activist. In the formative stages of my positionality work, I primarily identified with critical race theory [18,19,20] and critical whiteness studies [6,7,8]. However, as I was using these tools to ground myself and my positionality, I was feeling the compression and regurgitation of a false binary. With this in mind, I added racial identity development as another lever by which to conduct and humanize myself and the participants in my research. Racial identity development theories [21] underpin the advancement of human development through the lens of race and racialized experiences.

One of the questions I was asked during my dissertation defense was why I found it necessary to create race-grounded phenomenology when there have been many studies that include race in phenomenology. I found this to be an important question and opportunity to walk scholars through the mental leaps I encountered while conceptualizing this new methodology.

First, as I was navigating the literature, I saw a lot of phenomenology of race type research. When considering conducting a study on phenomenology of race I grappled with the notion of studies about race being conducted in a way that perpetuates this notion of race as Other. This did not sit well with the ways I wanted to honor the agency of myself as a Black scholar or the Black undergraduate participants. I also felt phenomenology of race studies were more indicative of understanding the essence of race, but not necessarily the racialized experiences of minoritized communities. Hence, a phenomenology of race was not a methodology that I felt would honor my own Blackness or Black Finesse exerted by the Black undergraduate students.

Second, I then considered critical race phenomenology. However, I have been witnessing a romanticizing of critical race theory in higher education and public administration spaces. By the romanticizing of critical race theory, I mean that folks are comfortable talking about the fact that race and racism exists. However, when it comes time to operationalize and implement ways to mitigate racism and shift to an antiracism frame, white fragility happens [22]. Furthermore, while critical race theory has a tenet concerning situating lived experience as expertise, I did not only want to rely upon counter-storytelling [23] inept of a call upon political science as a discipline to shift their epistemologies. Considering my lived experiences with white fragility and that of the participants, I knew simply conducting a critical race phenomenology would not be sufficient.

Third, I then shifted toward the bridging of theories in order to fully honor and humanize the “essence” of the experiences shared by the Black undergraduate students. I then centered what I call an eclectic of critical theories of race [10]. By centering an eclectic of critical theories of race, I intentionally made room for the nuanced ways in which race, racism, and white supremacy shows up while simultaneously honoring the critical agency [24] of myself as a scholar and that of the participants. “No one theory can possibly characterize all aspects of a given phenomenon” [25] (p. 120). Setting up the research design anchored in critical theories of race, allows for a research design that blends multiple critical epistemologies concerning race and includes a grounded approach through the data analyses while centering race in an a priori manner.

3.2. Unveiling the Call for Decolonial Futures: The Nexus of Past and Present

In order to call for decolonial futures, I situate my endarkened narrative inquiry into the internal tensions and mental leaps I had during my dissertation process. In order to transpose and tie the past (a look at my dissertation components) to decolonial futures, I use four anchors of decolonizing education to demonstrate how scholars can further commit to decolonizing their research albeit via dissertation processes or other research contexts. Beneath each of the four anchors of decolonizing education, are questions I asked of myself as a Black race scholar activist that can be useful for scholars who are wrestling with situating themselves and race in their research. I provide Table 1 as a quick synopsis and systematization of my thinking to build the following implications that follow.

Table 1.

Systematizing components of my dissertation through four anchors of decolonizing education.

3.3. Decolonizing the Mind through Ways of Knowing and Knowledge Construction

When considering the development of a dissertation, students are often given various advice to consider in building their own. Anything from knowing how many chapters there are “supposed” to be in a dissertation, to what each chapter must include, to how knowledge is supposed to be construed and discussed. Students are also often told to go look at dissertations that are in a similar field or area of interest as a primer or foundation to build from. I did all of the aforementioned in order to build my dissertation, but what needed to be further explored are the mental leaps and internal tensions I experienced along the way. Furthermore, my mental leaps informed the ways I even envisioned the design of the ways knowledge would be produced within those chapters as well.

As I was being cocooned in notions of inclusive excellence [26] in my doctoral program, I was at tension with what this meant for me as a Black race scholar activist. Was my Blackness apart of that inclusive excellence? Would centering Blackness not be considered inclusive? Would a focus on Blackness not contribute to the canon of literature in a way that would be able to be compared to other student populations? As I navigated all of these tensions, I reckoned with the fact that I expected my BIPOC faculty mentors to put their bodies on the line racially and therefore should do the same for and with the Black undergraduate scholars in political science that I partnered with for my dissertation. Because of a lot of emotional labor and internal tensions, I was reckoned with centering Blackness, not only for my own soul, but that of my participants. I knew that I needed a methodology that was inclusive of that labor. While I knew that I would produce a phenomenological study, I was grappling with what that would look like specifically for my study of Black undergraduate students in political science. I played around with different titles of my methodology and walked through different ways to conceptualize these ideas.

The word grounded in higher education is often attached to grounded theory. My advisor and I wanted to ensure that this was not simply a signal to that methodology, but simultaneously reflective of some of the grounded methodological insights in building a new methodology. I then decided to finalize and further conceptualize race-grounded phenomenology (RGP). Race being hyphenated with grounded is indicative of a description of the grounding or foundation necessary to conduct a phenomenology. Rather than doing a phenomenology of race, I inverted this to indicate the necessity of grounding race in order to understand phenomena particularly with a desire to decolonize methodologies and understandings of research. Furthermore, traditional practices of phenomenology [27] would have required that I engage in bracketing and not centering myself and Blackness in the research. The varied forms of phenomenology did not fit what I knew to be true as a Black race scholar activist who was once a student in political science spaces. Race-grounded phenomenology allowed me to decolonize the ways in which the essence of a phenomena are researched and understood.

3.4. Decolonizing Pedagogy

As a scholar who is committed to culturally relevant pedagogies [28,29], making Black Lives Matter in traditionally white institutions [1] and beyond, I wanted to ensure that my dissertation could be a teaching tool that scholars could glean upon to disrupt the ways in which we create and illustrate research. With this in mind, I leaned upon artistic methods not only within the data collection, but highly emphasized it within my analyses and dissertation defense as well. I knew that there was a hidden curriculum [30,31] being experienced with the research participants in my study. This may or may not have been their first encounter with a researcher, let alone a Black researcher. I dug into my internal tensions around what are the ways participants have experienced research? What are the ways the participants think of research? How can I demonstrate humanizing ways to engage in research that are identity affirming? How can I include other ways of sharing knowledge, so that participants are not only experiencing verbal dialogue?

Rather than simply rely on interviewing as a method, I shifted toward embodied methods of gathering ways of knowing which was indicative of asking participants to illustrate or draw their racialized childhood experiences and racialized experiences within political science. The images were not only illuminating of the pedagogies experienced within political science, but also sparked emotional responses because of the power of the imagery. This allowed for mind, body, soul connection to research. The null, hidden, and other forms of curriculum were unveiled from the images which helped me to conceptualize what I entitled the political science paradigm. “This is a term I use to operationalize the socialization of political science which is the status quo of the discipline. The status quo of the discipline is founded and grounded in whiteness [32]. The socialization of political science refers to the ways in which political science engages in and perpetuates structures, politics, and agency embedded within the status quo” [10] (p. 22).

Furthermore, my thinking around creating a sacred space with the participants was at the forefront of my decision making. My dissertation data collection began in the fall term of 2019 prior to COVID-19 and the national display of the murder of George Floyd, but I continued data collection into 2020. I knew I would be conducting a focus group as a part of data collection to bring the participants together to share teachings and wisdom with one another. However, given the sociopolitical context of COVID-19, the continued racial uprisings with the BLM protest, and institutionalized violence on Black bodies, I knew that this focus group had to have underpinnings of healing-centered engagement [33]. With this in mind, I ensured to position the participants as experts in the space among one another, but also for future scholars via writing as well. With this in mind, I wrote a poetic transcription or letter to future Black political science scholars as my last chapter of the dissertation to give them the final word as THE educator of the dissertation and research.

It is through the insights, wisdom, and teachings of the participants that I came to understand and conceptualize Black Finesse [10] as well which is further discussed in reimagining section.

3.5. Decolonizing Structures, Policies, and Practices

As a race scholar activist, I wanted to ensure my dissertation served as a model for disrupting the ways in which many of us have been socialized to think about the flow, structure, and practices around the development of a dissertation. I asked myself questions concerning how I have been researched as a Black body and also how I have digested structures of research. How can I insert my full self within each chapter to indicate how my positionality informed that chapter? How can I bring multiple theories together to make what is often invisible visible in race-grounded research? How can I do a literature review that is not simply a reproduction of the canon of research, but instead rooted in unveiling the “why and how” behind a new conceptual model of literature reviews? How do I name the structures embedded in political science without centering whiteness at the expense of the wisdom shared from the Black undergraduate students?

First, positionality has often been considered as problematic to include due to notions of objectivity in research or simply needed as a small section within a chapter. To disrupt the aforementioned notions, I put my positionality within each chapter of my dissertation with the exception of the last chapter which focused on the words of my participants. For instance, I had the following sections in my dissertation titled:

Chapter One: Positionality by way of introduction to the study;

Chapter Two: Positionality informs literature discussion;

Chapter Three: Positionality informs methodology;

Chapter Four: Positionality informs data illustration and findings;

Chapter Five: Positionality informs theory to praxis;

Chapter Six: Positionality informs significance, implications, and recommendations.

Second, rather than honing in on one theory to build a race-grounded phenomenology, I honed in on an eclectic of critical theories of race to unveil the visible and often invisibilized experiences of race in political science and higher education contexts. The eclectic of critical theories of race allows for the many layers of race, racial identity development, and racialization [34] to be revealed rather than only understanding the participants wisdom through one angle. I had concerns and reservations about producing a study that only focused on one angle of racialization because our bodies experience so much more than one angle. I wanted to ensure I honored the complexity, variety of emotions, and ways of knowing that comes with navigating political science as a Black undergraduate student.

Third, the literature review was theoretically informed in order to provide the foundation necessary to unveil the conceptualization of a race-grounded phenomenology. I really struggled with this chapter because I did not want to simply do a historical overview of Blackness, political science, or racialization. At the dissertation proposal stage, I did not have race-grounded phenomenology fully developed. I called it a critical race phenomenology at the time of my dissertation proposal. It was not until later that I came to a reckoning with the tensions of calling my methodology a critical race phenomenology. With this in mind, I was in the mud about the writing of my literature review without unveiling the methodology too soon within chapter two. I needed to move through the muddiness of what to call my methodology and how to write a theoretically informed literature review that builds the foundation for the methodology chapter without duplication. In order to help me make the mental leaps necessary to conceptualize my methodology and write a literature review that helps me to transition to chapter three my dissertation advisor told me, “Put the models [methodologies] side by side...show where we have been in the literature review.” Her advising me to do this gave me the ability to strive forward toward building a “theoretically informed literature review” [10]. I created a literature review that bridged the eclectic of critical theories of race and argued for why this was necessary to keep my soul connected to the research and to honor the minds, bodies, and souls of my participants.

Lastly, I knew that I would have to talk about whiteness being embedded in the discipline of political science given the ways in which it is incubated within higher education. However, I did not want to obsess over whiteness in a study that was meant to honor and humanize the Black Finesse of the undergraduate students. With this in mind, I opened myself up to the unknown with how I conceptualize this in the dissertation. At the point of my dissertation proposal, I used the term political scienceNess to try to conceptualize the essence of political science as indicated by the participants. By the time I had completed my data collection, I conceptualized the political science paradigm as the way to discuss the essence of what the Black undergraduate students navigated. Using a phenomenographic method [13] positions participants to have more of a role in the data analysis and shared meaning making. The shared meaning making for data analyses was pulled via artistic methods. I leaned upon the images created by the participants that revealed the ways in which agency, action or inaction, was used by the political science professors. The prompt used with the participants for the artistic illustration was “Please draw or illustrate how you navigate race in your political science classrooms.” Using artistic methods allowed for the structures felt on the bodies of the Black undergraduate students to be felt, sensed, and heard differently than the written word. The conceptualization of the political science paradigm allowed for me to critique the structures embedded within political science as experienced by the participants. Indicating that the participants experienced the political science paradigm allowed me to acknowledge whiteness without centering whiteness at the expense their Black Finesse.

3.6. Reimagining Higher Education from a Decolonized Lens

As a Black race scholar activist who was a political science student and educator, I wanted to ensure I disentangled Black pain from agency. While the political science paradigm is focused on the ways agency occurred from that of the professor, the agency of the Black undergraduate scholars had to be unveiled and honored as well. How do I reconceptualize the validity of my qualitative research that pushes on normative notions of validity? How do I not perpetuate the fetishization of Black pain? How can I make what is often invisibilized by whiteness visible? How can I reimagine a way to conceptualize the labor of the Black undergraduate students amidst the political science paradigm?

The beauty of qualitative research is the often nuanced accounts of people and their experiences. However, validity is often at the crux of many discussions and moments of interrogation when the research is centered on race. Fortunately, my committee had the epistemological lenses and ethos necessary for me to feel a sense of comfortability to push on normative forms of validity. However, I still needed to know what validity would look like and feel like for myself as a Black race scholar activist. Validity for me was at the crux of the design, the defense to the publication of the dissertation. By way of design, I anchored into artistic methods to allow for an embodied way of knowing to be revealed and expressed by participants. I shared of myself as well to repudiate an extractive and transactional experience for the participants. I also wanted there to be a glimpse into what research can look like and feel like from a humanizing and healing-centered engagement [33] lens to ensure the participants’ experiences were that research does not have to perpetuate harm. I wanted the participants to feel invigorated, encouraged, dignified, and soul filled after engaging in research with me from the initial point of contact to the dissertation defense. At my dissertation defense, I leaned on the artistic illustrations of the participants and visual conceptualizations of Black Finesse and methodology to reimagine the ways in which knowledge and validity of that knowledge is shared by a PhD candidate. I anchored my findings in theory to further undergird the validity of my findings as well.

Often times, within research on race and racialization, whiteness can obfuscate and suffocate the revelation of how agency is used by Black folks. I wanted to ensure this was not the case which is why I developed the concept of Black Finesse to hone into the agency and ways of knowing exhibited from the Black undergraduate participants. Below are some quotes from my dissertation to help further understand the ways I conceptualized Black Finesse:

“Black Finesse reflects the expertise, flair, knack, artfulness, and/or skills through which Black students navigate structures, and politics via their agency...Black Finesse recognizes Blackness alongside and in spite of racialized experiences; hence, individuality and personality as well [12]”.[10] (p. 20)

“Black Finesse is not simply bound to an understanding of race in political science, but Black Finesse is grounded in the ways of knowing that the students developed from their familial capital [35], prior racialized experiences, individuality and beyond”.[10] (pp. 122-123)

“While we are all racialized, Black Finesse stems from Black students’ abilities to be grounded in oneself while simultaneously engaging in identity enactments.”[10] (p. 132)

I desired to reimagine a way of reflecting research on race that allowed Black folks to walk away knowing where dignity and agency was reflected. I wanted to reflect back to my participants the ways in which their agency was honored, acknowledged, and celebrated. I wanted to make the often invisibilized labor of the Black undergraduate students, visible. I leaned on Cross et al. identity enactments [12] to reflect the psychological negotiations [10] inter and intracially that the Black undergraduate scholars make just to simply be a Black undergraduate student in higher education and amidst the political science paradigm. There is a lot of mental and emotional labor that is often invisibilized and not considered nor celebrated. It is one thing to identify whiteness, but it should not come at the expense of naming and unveiling Black Finesse. Often times, once whiteness is identified there is a scurry to wrestle with that and then that is imposed on Black bodies in higher education classrooms and equity and inclusion committees. I committed to centering Black Finesse as another anchor to consider when engaging in race dialogues and ways to navigate race in higher education. While Black Finesse provides a wider purview to understand race and racialization in higher education, it does not mean that Black students and faculty should be positioned in tokenizing ways or exploited through service labor.

4. Conclusions

This article demonstrates the ways in which the building of research within the dissertation process can allow for the manifestations and cultivation of decolonizing higher education. In order to continue unmaking the canon [36], we all have a role in our research agendas to ensure the continued revealing of our mental leaps and internal tensions as ways to build the efficacy and praxis of decolonizing higher education. More importantly, we must decolonize higher education to create humanizing education contexts, identity affirmation, and honoring Black minds, bodies, and souls. We cannot expect Black scholars to take on the work of decolonization from their positionality inept making visible our mental leaps, internal tensions, and strategic pivots to keep our souls connected to research. We must go inward prior to development and engagement with notions of diversity, equity, and inclusion work in higher education to mitigate further cultural taxation [37] of Black faculty, racial battle fatigue [38], and exploitation of our emotional labor and well-being.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Tuitt, F.; Haynes, C.; Stewart, S. Transforming the classroom at traditionally White institutions to make Blacklives matter. Improv. Acad. 2018, 37, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museus, S.D.; Quaye, S.J. Toward an intercultural perspective of racial and ethnic minority college student persistence. Rev. High. Educ. 2009, 33, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClish-Boyd, K.; Bhattacharya, K. Endarkened narrative inquiry: A methodological framework constructed through improvisations. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2021, 34, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, C.B. Learning to (Re) Member the Things We’ve Learned to Forget: Endarkened Feminisms, Spirituality, and the Sacred Nature of Research and Teaching. Black Studies and Critical Thinking; Peter Lang New York: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Lerma, V.; Hamilton, L.T.; Nielsen, K. Racialized equity labor, university appropriation and student resistance. Soc. Probl. 2020, 67, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillborn, D. Education policy as an act of white supremacy: Whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. J. Educ. Policy 2005, 20, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.I. Whiteness as property. Harv. Law Rev. 1993, 134, 1707–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardo, Z. The souls of white folk: Critical pedagogy, whiteness studies, and globalization discourse. Race Ethn. Educ. 2002, 5, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lather, P. Getting Smart: Feminist Research and Pedagogy within/in the Postmodern; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, J.Z. Black Finesse Amidst the Political Science Paradigm: A Race-Grounded Phenomenology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, C. WEB Du Bois and caste education: Racial capitalist schooling from reconstruction to Jim Crow. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 54, 23S–47S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, E.W., Jr.; Seaton, E.; Yip, T.; Lee, M.R.; Rivas, D.; Gee, C.G.; Roth, W.; Ngo, B. Identity work: Enactment of racial-ethnic identity in everyday life. Identity 2017, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlgren, M.A.; Hult, H.; Dahlgren, L.O.; Hård af Segerstad, H.; Johansson, K. From senior student to novice worker: Learning trajectories in political science, psychology and mechanical engineering. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J. Conversations with James Baldwin; University Press of Mississippi: Jackson, MS, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. The meanings of methodology. Soc. Res. Methods 2000, 60, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Tuitt, F.; Stewart, S. Decolonising Academic Spaces: Moving Beyond Diversity to Promote Racial Equity in Postsecondary Education. In Doing Equity and Diversity for Success in Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K.; Gotanda, N.; Peller, G. Kendall Thomas. In Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, R.; Stefancic, J. Critical Race Theory; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dixson, A.D.; Rousseau, C.K. And we are still not saved: Critical race theory in education ten years later. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.E., Jr.; Parham, T.A.; Helms, E.J. The Stages of Black Identity Development: Nigrescence Models. In Black Psychology; Cobb & Henry Publishers: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- DiAngelo, R. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Solórzano, D.G.; Yosso, T.J. Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qual. Inq. 2002, 8, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, B. Race-related service and faculty of color: Conceptualizing critical agency in academe. High. Educ. 2000, 39, 363–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.L.; Dangerfield, L.C. Defining Black Masculinity as Cultural Property. In African American Communication & Identities: Essential Readings; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, C.; Tuitt, F. Weighing the Risks: The Impact of Campus Racial Climate on Faculty Engagement With Inclusive Excellence. J. Profr. 2020, 11, 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Human Science Perspectives and Models. In Phenomenological Research Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy in African-Centered Schools: Possibilities for Progressive Educational Reform. In African-Centered Schooling in Theory and Practice; Stylus Publishing LLC: Sterling, VA, USA, 2000; pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: Aka the remix. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2014, 84, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, J. Negotiating the gaze and learning the hidden curriculum: A critical race analysis of the embodiment of female students of color at a predominantly White institution. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. (JCEPS) 2011, 9, 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A.; Penna, A.N. Social education in the classroom: The dynamics of the hidden curriculum. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 1979, 7, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, J. Race and the Making of American Political Science; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright, S. The future of healing: Shifting from trauma informed care to healing centered engagement. Occas. Pap. 2018, 25, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Omi, M.; Winant, H. Racial Formation in the United States; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yosso, T.J. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 2005, 8, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S. Towards the Unmaking of Canons: Decolonising the Study of Literature. In Doing Equity and Diversity for Success in Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, W.G.; Bensimon, E.M. Promotion and Tenure: Community and Socialization in Academe; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.A. Black Faculty Coping with Racial Battle Fatigue: The Campus Racial Climate in a Post-Civil Rights Era. In A Long Way to Go: Conversations about Race by African American Faculty and Graduate Students; Peter Lang New York: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Volume 14, pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).